ABSTRACT

Management models are needed that empower local communities to produce biofuel feedstock in a manner that drives rural development. Much can be learnt through the accumulated experiences of sugarcane outgrower schemes in southern Africa. Early schemes provided limited empowerment, but protected outgrowers from the risks of volatile sugar value chains. In later schemes, processing plants were responsible for all operations and simply paid dividends to participating farmers. More recent schemes offer full ownership, which comes with greater rewards and empowerment, but also exposure to risks. The underlying institutional structures of outgrower schemes largely dictate their performance, and thus the factors that affect their viability or collapse. To understand the different institutional arrangements of sugarcane outgrower schemes we undertake a comparative analysis of 13 schemes in southern Africa employing a political economy framework that uses the three key questions: ‘who owns what’, ‘who does what’, and ‘who gets what’.

1. Introduction

In southern Africa, the rural development potential of biofuels feedstock production is a more important driver of biofuel expansion than climate mitigation, which has driven biofuel production in developed countries (von Maltitz & Stafford, Citation2011; Gasparatos et al., Citation2015). If countries in the southern African region choose to produce larger quantities of biofuels, then it is critically important they this in a socially responsible way that maximises local community benefits. Increasing biofuel production and use in southern Africa can potentially generate macroeconomic benefits for both South Africa (as the major country of consumption), as well as neighbouring countries that can accommodate feedstock production at lower costs (Hartley et al., Citation2017).

Currently, sugarcane appears to be the most promising biofuel crop, as southern Africa has a long and successful sugar industry, which can form the foundation for sugarcane ethanol production (Watson, Citation2011). However, sugarcane production can have environmental and socioeconomic impacts (Gasparatos et al., Citation2015, Citation2018). Hess et al. (Citation2016) conclude that sugarcane production is, in general, neither explicitly sustainable nor unsustainable, but the impacts depend substantially on different factors.

There is a widespread recognition that sugarcane production can be a good development strategy, as the crop can be easily gown by rural communities (Terry & Ogg, Citation2016). In several rural contexts of southern Africa it has been found that sugarcane production reduces poverty (Herrmann & Grote, Citation2015; Mudombi et al., Citation2016), increases food security (Herrmann, Citation2017), and brings general development opportunities to the local economies, including infrastructure and secondary industries (Shumba et al., Citation2011; O’Laughlin, Citation2016). In addition sugarcane is one of the biggest contributors to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Swaziland (16%), Zambia (3%–4%) and Malawi (1.3%) (Terry & Ogg, Citation2016).

Some of the main criticisms of sugarcane include the: (a) displacement and loss of access of local communities to land (Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010a, Citation2010b); increased local food insecurity (Terry & Ryder, Citation2007); low employment compared to conventional agriculture (Dubb, Citation2016); arduous working conditions and low salaries and most work being seasonal (Richardson, Citation2010; Richardson-Ngwenya & Richardson, Citation2014); social and health impacts of influx of migrant labour (O’Laughlin, Citation2016); and undue political influence from the strong vested interests of the sugar industry (Dubb, Citation2016).

Some of these concerns are linked to the economics of the crop, but most are linked to the institutional arrangements of production projects. Many of these concern can be mitigated if projects are established and implemented in a socially-responsible manner (Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010b). Of particular importance is how land is acquired for biofuel feedstock production and how individual feedstock growers are involved in biofuel value chains (Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010a; Gasparatos et al., Citation2015).

There is extensive literature on the impact of large-scale land acquisitions for biofuel feedstock production in Mozambique, Zambia, South Africa and Madagascar (Conigliani et al., Citation2018). This literature points to the negative impact of land acquisitions on adjacent local communities (Cotula et al., Citation2009; Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010a; Hall, Citation2011; Matenga & Hichaambwa, Citation2017). The land acquisition processes, including how local communities experience the effects of land transferring and how these effects can be mitigated is extensively researched (Vermeulen et al., Citation2009; Cotula & Leonard, Citation2010; Vermeulen & Cotula, Citation2010b). The literature also explores the land use dynamics around commercial sugarcane plantations and outgrower schemes (Hall et al., Citation2017).

To ensure that the benefits of biofuel feedstock production extend beyond the companies that operate the large-scale plantations, governments and investors in southern Africa have developed models that involve local small-scale (peasant) farmers. These include, among others, different types of contract farming schemes, joint ventures, management contracts, community leases, and new supply chain relationships (Cotula & Leonard, Citation2010). Such models may have the potential to ensure greater equity, local ownership and community empowerment (Terry & Ogg, Citation2016), and form the basis of this comparative analysis.

In southern Africa almost all large sugar-processing plants have a core sugarcane estate that is owned and run by the mill. In addition, many of the large sugar mills source additional sugarcane from small produces referred to as outgrowersFootnote1 (Glover, Citation1984; Richardson, Citation2010). These outgrowers can consist of individuals or groups of farmers in collective structures such as trusts, cooperatives or companies. The farmers typically enter into a contractual agreement to grow sugarcane specifically for a processing plant and are often referred to as contract farmers. Eaton & Shepherd (Citation2001) define contract farming ‘as an agreement between farmers and processing and/or marketing firms for the production and supply of agricultural products under forward agreements, frequently at predetermined prices’. Such agreement help farmers gain access to markets, infrastructure, and technology, but with the local knowledge, flexibility, and superior incentives of smallholders (Deininger & Byerlee, Citation2012). Access to seeds, fertiliser, credit and extension services is often provided as an advance against final crop delivery (Prowse, Citation2012). Contract farming normally gives exclusive purchasing rights to the processing plant with which the smallholders have made the contractual agreement, but this is a moot point in sugarcane production where the processing plant is typically the only available market optionFootnote2. Depending on their location, sugarcane outgrower schemes can be either irrigated or rainfed (dryland). When irrigated, financing to install and maintain the irrigation infrastructure has to be acquired and repaid which adds layers of complexity to irrigated sugarcane outgrower schemes compared to dryland farming. In addition, both national governments and processing plantsFootnote3 have formed institutions to support the farmers in such endeavours. While governments see irrigated sugarcane production as a major opportunity for rural development, companies view outgrowers as a substantial source of sugarcane that can allow them reach the full operating capacity of their mills (Dubb, Citation2015; Terry & Ogg, Citation2016). The way that sugarcane farmers are organised, and the support they receive, can have profound impacts on the success of their farming activities (Dubb, Citation2015, Citation2016). Within the sub-region, there has been an evolution in the way outgrowers are organised and the core to this paper is attempting to understand how these structures impact on the risks and rewards to the farmers.

Dubb et al. (Citation2017) suggests that much of the current outcomes of the sugarcane industry are due to the context-specific political-economic relationships between different stakeholders. Understanding the different institutional arrangements in the sugarcane sector is a pre-condition for developing policies to improve outgrower systems. The main aim of this paper is to identify the institutional arrangements in southern African sugarcane outgrower schemes, and the aspects that work well and can be incorporated in other relevant projects, versus what work badly and should be avoided. To achieve this we use a Political Ecology approach that employs the main agrarian political economy questions of Bernstein (Citation2010) to analyse 13 outgrower schemes in southern Africa.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research approach

We adopt an agrarian Political Economy approach that takes into account how land and agrarian dynamics are shaped by political institutions and processes in light of external economic pressures (Borras et al., Citation2010; White & Dasgupta, Citation2010; Munro, Citation2012). Political Economy can help unravel the roles on institutions in shaping the land and agrarian dynamics in smallholder settings (Bernstein, Citation2010; Chinsinga et al., Citation2013).

To understand the different institutional arrangements of the sugarcane industry the three essential agrarian Political Economy questions of Bernstein (Citation2010) are used, ‘who owns what’, ‘who does what’, and ‘who gets what’. These questions are essential in understanding institutional arrangements, power asymmetries, and class dynamics in smallholder settings in Africa (Borras et al., Citation2010; White & Dasgupta, Citation2010). Bernstein (Citation2010) argues that every productive landscape has different classes of labour and institutions shaping their interactions.

The question (‘who owns what’) seeks to unravel the levels of equity between local farmers and the developers during project initiation, and is context specific to the local tenure system. The question (‘who does what’) seeks to untangle the understanding of the project initiations, and in addition it addresses the understanding of the management regimes and practices related to land. The question (‘who gets what’) addresses the institutional aspects of risk spreading and sharing among the ‘rights-holders’ and the ‘duty-bearers’ as well as the overall empowerment outcomes.

We use 13 case studies of sugarcane outgrower schemes in South Africa, Zambia, Swaziland, Mozambique and Malawi, the main growing regions in southern Africa ( and supplementary material). The term outgrower is used to describe any individual smallholder farmer (or group of farmers) that grow sugarcane specifically for sale to a local sugar-mill. We exclude from this analysis large-scale commercial farmers (e.g. those commonly found in South Africa), and focus only on farmers from ‘peasant-farming’ communities.

Table 1. Key characteristics of the study core plantation and outgrower schemes – see the supplementary material for a full description of each project.

Data was obtained for studies undertaken by the authors (e.g. see Mudombi et al., Citation2016; Terry & Ogg, Citation2016), as well as from secondary data and key informant interviews. Furthermore, some of the co-authors have been instrumental in setting up and/or supporting some of the projects discussed in this paper, and have intimate personal experience and insider knowledge. This was supplemented with information from project reports and academic literature.

A two-stage analysis was used. The history and operation of each outgrower scheme was evaluated against the following criteria:(a) aspects of land acquisition, ownership and use; (b) cost sharing arrangements and financing of operations; (c) institutional structures related to outgrower operations; (d) payment and benefit-sharing arrangements; (e) role of authorities and regulators; (f) role of the processing plant; (g) yields of the core plantation and the outgrower schemes; and (h) perceptions on success and failure of the project. For some schemes data was not readily available for all the criteria. Subsequently we used this information to answer the three Political Economy questions outlined above, to derive a typology of outgrower schemes and policy recommendations.

2.2. Study sites

Sugar production dates back to the 1860s in South Africa, 1890s in Mozambique, 1950s in Swaziland, 1960s in Zambia and 1970s in Malawi. In South Africa the sugar sector was initially operated by colonial farmers, but was later dominated by large corporations with the development of large processing plants (Dubb, Citation2016). In other southern Africa countries, corporations operated the large block sugarcane plantations from the beginning. These corporations were either state-run (e.g. RSSC in Swaziland) or private (e.g. Illovo in Malawi). Small-scale sugarcane production through outgrowers dates back to the 1930s in South Africa, with the major expansion initiated in the 1970s (Dubb, Citation2016). Such outgrower models were introduced into the other southern Africa countries between the 1980 and 2000s ().

In most cases the outgrower schemes were initiated a few decades after the core plantations. In Mozambique, projects collapsed during the civil war, and it is only recently that they have been rejuvenated (Dubb et al., Citation2017). A full description of the projects is provided in the supplementary material. In cases where a number of projects or community associations operate in a relatively similar fashion these are considered together as a single project typeFootnote4. However, where phases of outgrower establishment linked to the same processing plant have differed substantially, these are considered individually.

Projects included in this analysis are either dryland or irrigated farming. Depending on the project, outgrowers farmed their own land, or were grouped into formal structures pooling land and undertaking sugarcane production in a single block. In some cases, despite small-scale farmers being involved, management was undertaken by a management agency using paid labour ().

Table 2. Size, ownership and inclusion characteristics of the study outgrower schemes.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Who owns what: land ownership during project initiation and operation

Outgrower schemes were almost exclusively established within areas under traditional land tenure regimes where local communities have usage rights rather than freehold tenure. The allocation of agricultural plots within projects ranged from fully individual owned and managed plots to different forms of communal allocations.

Large plantations and processing plants typically have long-term leases or in a few cases the full title of the land they use for their operations. Outgrower projects may be located on (a) land for which the processing plant holds the title, (b) community land, (c) land where the title is registered under the outgrower project structure or (d) land returned to communities through land reform projects (in south Africa).

In most outgrower sugarcane projects, and especially for irrigated projects, a single large block plantation is established so as to reduce costs and facilitate the development and operation of the irrigation infrastructure. This requires community members to relinquish existing tenure rights before a group structure could be established for the outgrower project.

For almost all irrigated outgrower projects, land ownership patterns were altered during their establishment (). In all cases, except the Kaleya project in ZambiaFootnote5, the general principle during project development appears to be that in order to be included in the sugarcane outgrower scheme, farmers had to have pre-existing access to the land or be members of the local community whose land will form the basis of the outgrower project. However, in many cases individuals become involved in sugarcane outgrower projects despite not meeting the above criteria (Matenga & Hichaambwa, Citation2017). Overall, we notice four land allocation mechanisms that are not, however, mutually exclusive.

Allocation pattern 1: Farmers were allocated into the scheme, typically by chiefs or government officials (Adx, Dwangwa irrigated, Pongola, Kaleya). Although this allocation was typically reserved for members of the local community, there have been several instances of outsiders (usually politically connected) gaining access to these outgrower schemes.

Allocation pattern 2: Schemes recommend a minimum land holding that can provide for economically profitable and viable sugarcane production (Magobbo, Kaleya, and the original KaNgwane outgrowers). Some form of land trading was often needed to ensure that farmers had sufficient land to enter the scheme. This rather paternalistic approach is based on what the project managers estimate to be the minimum size for economically profitable and viable sugarcane production. Land holdings within such outgrower projects were typically larger than the mean areas of outside landholdings. As a consequence some community members have been denied involvement, or in the worst cases some local farmers lost their agricultural land holdings.

Allocation pattern 3: Individual farmers decide on what proportion of their existing land holding to allocate for sugarcane production. This is the most common approach in most dryland schemes. It also occurs in some of the irrigated outgrower projects such as AdX.

Allocation pattern 4: Land is converted from individual farms land to land that is owned by a group through some form of group ownership entity such as a trust, company or cooperative. The farmers effectively become shareholders of this land ownership entity. The degree of true ownership that community members have differs widely, as the state or processing facility retains a high degree of ownership in many projects. This model is most advanced in Swaziland, and was a key element of the SWADE project, where individual farmland was returned to the King, who re-allocated it to farmer-owned companies where all the farmers are equal shareholders regardless of the size of their original land holding.

3.2. Who does what: land management and project initiation

3.2.1. Land management

Sugarcane cultivation requires extensive and dedicated labour during specific phases such as planting and harvesting, but has a relatively lower labour requirement during other times of the year. In most of the outgrower schemes, contractors are used for planting, harvesting and haulage. Three distinct land management trends were observed ():

Management model 1: The farmers managed their own land for day-to-day activities, but might rely on external labour for re-planting and harvesting. This model was found in most dryland schemes but only observed in the AdX irrigation project where, although the farmers manage their land, this was done under strict guidance from the processing plant.

Management model 2: Land is managed by a management company that does all, or most, of the work on behalf of the farmers (Dwangwa irrigated, Magobbo and TSB).

Management model 3: Farmers form a trust or company that owns and manages their combined land holding. This model is most developed in the SWADE project area, and is likely to be a core feature of the Maragra project in Mozambique. We differentiate this from the management model 2 in that the farmer-owned companies control the subcontracting processes.

3.2.2. Project initiation and support

The degree of involvement of the state versus that of the processing plant differed through the region. As highlighted by Dubb (Citation2017), the sugar industry is one of the largest economic sectors in some countries in southern Africa (e.g. Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland), and can thus become a powerful lobby.

A critical need was identified for tight links between mills and growers to ensure that cane is delivered correctly following the pre-determined schedule and volume. Cane rapidly deteriorates in both condition and value following harvesting, and must be delivered to the mill in the least possible time. In addition mills need a well-defined and predictable supply of sugarcane daily during their operating season. Therefore it is important to establish both scheduled deliveries, as well as compensation mechanisms such as the relative RV%Footnote6 system, which can ensure that growers are not disadvantaged by harvesting outside of periods that could give them peak value. South Africa and Swaziland have specific legislation and strong independent industry associations that dictate how profits from sugar production are to be distributed between growers and processing plants (Dubb, Citation2016; Terry & Ogg, Citation2016). Zambia, Mozambique and Malawi use similar principles though this is not legislated.

The degree to which the processing plant and the state are involved in the establishment and operation of outgrower projects differ (). Some outgrower projects were initiated and led by government, through specific agencies that form a buffer between the processing plant and the outgrowers. Such agencies have a strong rural development focus. Alternatively projects were initiated by the processing plant (sometimes with government support), through agencies that link the outgrowers to the processing plant.

Table 3. Institutional responsibility in setting up and supporting outgrower schemes.

Examples of outgrower projects initiated and led through strong government involvement include the Dwangwa irrigated scheme in Malawi, and the SWADE scheme in Swaziland. In both cases the state was responsible for project initiation, with state-sponsored institutions forming a buffer between the outgrowers and the processing plant. In Malawi, the Dwangwa-Cane-Growers-Trust (DGCT) and Dwangwa-Cane-Growers-Limited (DCGL) are largely government-dominated at the board level, but are independent and funded through a tax on the irrigated farmers supportedFootnote7 (Chinsinga, Citation2016). In Swaziland, SWADE is a government funded parastatal with development focus that was responsible for establishing the irrigation infrastructure and providing support to outgrower associations (Terry & Ogg, Citation2016).

South Africa underwent radical changes in the way that the state was involved in the development and operation of outgrower schemes. While there is currently low state intervention, and a stronger linkage between outgrowers, processing plants, and other industrial players, this was not always the case. In the early days of the KaNgwane projects, a state-run agency, Agrowane, acquired financing, developed infrastructure and supported outgrowers. When Agrowane collapsed during the integration of the KaNgwane into South Africa, its support stopped and many outgrower schemes collapsed. The TSB company has taken on many of the functions previously played by Agrowane.

In Zambia, the state played a strong role in the development of the different outgrower schemes, but with a large degree of support from the processing plants. In South Africa (Nkomazi project) and Mozambique the processing plants appeared to be the ones initiating the outgrower projects, fulfilling many key functions such as providing assistance to secure loans for infrastructure. Some processing plants created specific support arms or companies to undertake the outgrower support. In some cases these companies have managed the farming activities (AdX, Kaleya), but in other cases have completely taken over the actual farming activities (TSB, Monyonyo).

3.3. Who gets what: outcomes of involvement in outgrower schemes

3.3.1. Empowerment, risks and rewards

The existing literature and project experience is not conclusive about the impact of sugarcane production to outgrowers and workers. O’Laughlin (Citation2016) has documented examples of low-paid seasonal labour in sugarcane plantations, with debatable benefits to labourers. In South Africa, some outgrower project collapsed due to low returns (Dubb, Citation2016, Citation2017; James & Woodhouse, Citation2016). Despite this the general trend seems to be that farmers engaged in sugar are better off than the average farmers in the same area, with some having been able to amass considerable wealth.

Matenga (Citation2016) documented that income increased from US$50 to between US$900 and 1000 per month for outgrowers involved at the Magobbo scheme. On average outgrower households were receiving US$2999 per annum, substantially higher than non-outgrower households (though outgrowers may have sacrificed food production to achieve this) (Matenga, Citation2016). Schupbach (Citation2014) reported that outgrowers in the KASCOL project had greater wealth as measured through accumulation of assets, compared to farmers not involved in the project.

Participation in the KaNgwane projects allowed some individual farmers to amass extensive wealth prior to project collapse (James & Woodhouse, Citation2016). In these projects, consolidation of land led to a fewer farms with larger land holdings, and eventually to the emergence of a new class of medium-sized sugarcane growers. The subsequent models set up by TSB in the same area, seem less successful in terms of dividends paid to participating outgrowers, though it also paid land leasing fees (James & Woodhouse, Citation2016). Sugarcane yields have decreased substantially in many of the dryland farming areas in South Africa, and these farmers increasingly find sugarcane production to be uneconomical on their small landholdings, probably as a result of a decline in the market value of sugar (Dubb et al., Citation2017).

The outgrower schemes in Dwangwa have brought substantial financial returns to sugarcane farmers. Irrigated farmers typically have larger land holdings than dryland farmers, higher per hectare yield and higher per hectare net income (US$ 299 versus US$148 per ha) (Landell Mills Limited, Citation2012). Atkins (Citation2014) reported that economic returns to irrigated farmers range between US$ 2921 and 3297 per ha annually, compared to US$ 1831 per ha annually for dryland farmers (before financing costs and tax) for ratoon years. In the first harvest year rainfed farmers make a positive return of US$ 831 per ha, whilst irrigated farmers carry a large debt of between US$ 7100 and 9332 per ha. The internal rate of return for irrigation is only 25%–28% compared to 928% for dryland farming. Cisanet (no date) found that total deductions to the sugarcane revenue was 26%–29% for dryland farmers, compared to 37% for irrigated farmers, indicating the high overhead costs associated with the DCGL infrastructure. However many of the irrigation risks are borne by the DCGL and not the farmers. Clearly the risk and reward profiles are very different between irrigated and dryland cane production. The dryland farmers are not burdened with loan repayments and have more direct access and channels of communication with the processing plant. Dwangwa irrigated sugarcane farmers have generally lower levels of multi-dimensional poverty and higher levels of food security than dryland farmers and groups not involved in sugarcane production (Mudombi et al., Citation2016; Herrmann, Citation2017).

The SWADE projects significantly improved the livelihoods of those involved (Terry & Ogg, Citation2016; Mudombi et al., Citation2016). In addition to dividends from the sugarcane sales, outgrowers have also received numerous additional benefits such as piped clean water to the homestead and improved road infrastructure. Participating outgrowers were the true owners of the sugar growing enterprises and directly controlled its management. Furthermore, the farmers had direct accountability over the loans used for setting up their community plantations and associated infrastructure. In this model the farmers were well empowered and could potentially gain high financial rewards, but also directly carry most of the risk. This was illustrated by their low capacity in disaster preparedness as witnessed during the 2015–2016 drought (Mhlanga-Ndlovu & Nhamo, Citation2017).

The outcomes of involvement in outgrower dryland schemes seem to differ throughout the region. Dryland outgrower schemes in South Africa performed well in the past, but are struggling at present (Dubb, Citation2016; James & Woodhouse, Citation2016). This is largely due to a decline in the profitability of sugarcane, and possibly to the greater need for high incomes in the predominantly cash-based economy of the country. While this decline is true for both large-scale commercial farmers and outgrowers, the actual outcomes to outgrowers appear to be worse, possibly due to their smaller landholdings. However, despite the generally lower income received under dryland condition, in some ways dryland farming can have better economic returns than irrigated farming (see above). Furthermore, dryland farmers have far greater autonomy and decision-making power over land allocation for sugarcane than their irrigated counterparts.

Sugarcane yields varied considerably between the different outgrower schemes, and the core estates of the processing plants (). Many of the outgrower schemes, were able to meet or exceed the yields of the core estates , suggesting that from a yield perspective outgrower models can be as good as (or better) than corporate plantations. Some outgrower schemes were entirely run by the processing plant in the same way as their own estate. In such cases it is unsurprising that the obtained sugarcane yields are very similar to the yields of the core estate. For those outgrower schemes in which infrastructure had fallen into disrepair, yields had also fallen sharply. This clearly indicates the high risk to outgrowers associated with maintaining the infrastructure, especially in state-led initiatives, where farmers were not empowered to maintain it themselves.

Table 4. Yield comparisons between outgrower schemes and core plantations.

In many of the projects there was a low degree of community empowerment in term of involvement in decision-making and/or capacity building ( and ). In some cases the outgrowers were in effect, labourers on their land (AdX) or simply receive a dividend (TSB joint ventures, Magobbo). In these cases the outgrowers either were paid on the basis of their labour or simply receive a dividend, or both. In many cases (TSB, Magobbo, irrigated Dwangwa) the entire farming operation is managed on behalf of the outgrower farmers. In essence most risks from the farming activity are removed from the farmers, but they pay a high proportion of their income to the management agency.

Table 5. Outgrower level of empowerment in decision-making (either as individuals or management group).

Table 6. Responsibilities and income split among stakeholders.

In some outgrower schemes such as Keleya and AdX participating farmers manage their land, but under close supervision by the company. This reduces considerably their ability to make their own management decisions. This high degree of compliance and oversight had mixed benefits, with many outgrowers achieving lower yields than company estates. In South Africa some irrigated schemes had largely collapsed due to collapsed infrastructure, causing many farmers to discontinue sugarcane farming (Dubb, Citation2016). On the other hand dryland farmers, often had total control of their sugar farming enterprise, but receive very limited support from the sugar industry or the state. While belonging to grower associations helped increase their bargaining power, acquiring operational funding remained problematic.

All outgrower schemes have developed mechanisms to increase their purchasing power and allow them to obtain better rates for agricultural inputs (). In many cases the processing plants assist the bulk purchase of agricultural inputs, as well as the financing of the inputs through loans against sales. Processing plants and state-led institutions also commonly assist outgrowers in accessing improved technology, production practices and sugarcane varieties.

Table 7. Ability of outgrowers to obtain benefits of scale for land preparation, access to inputs, access to services and negotiating power.

3.3.2. Gender outcomes

Traditionally, in most parts of southern Africa, the cultivation of subsistence food crops is a female-oriented activity. However, land is mostly ‘owned’ by males, with land inheritances being mostly patrilineal. As such it is men that have predominantly benefited from outgrower sugarcane expansion. For instance in the SWADE, Zambia and South African projects most landowners were male, as most of the land was originally registered to males. Few females were engaged in the Magobbo outgrower scheme, while female wages in the scheme were worse than in the block plantation (Matenga, Citation2016). Sugarcane dividends tended to be captured by men, while women were usually charged with the production of food crops for home consumption on dryland farms if these are retained (see Matenga, Citation2016). Furthermore, due to the arduous nature of labour in sugarcane plantations much of the labour, was provided by males (Matenga & Hichaambwa, Citation2017). Regardless of the outgrower model, truly empowering and involving females meaningfully (and beyond low paid labourer jobs) in outgrower schemes appeared to be a major constraint across the sub-region for all the investigated schemes.

3.4. Towards a typology of outgrower schemes and policy recommendations

summarises the main characteristics of each outgrower scheme following the political economy questions outlined above.

Table 8. Synthesis of institutional arrangements along the three Political Ecology questions.

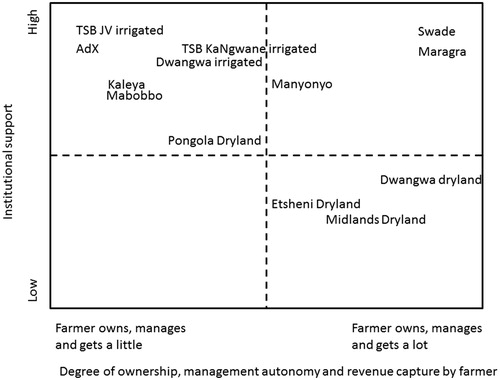

attempts to develop a typology of outgrower schemes, based on tenure security, management autonomy, access to dividends, and institutional support. The left side of the x-axis indicates outgrower schemes whose members have low tenure and low management autonomy; the middle schemes that offer either strong tenure or management autonomy, and the right side schemes whose outgrowers have both strong tenure and management autonomy. The x-axis largely reflects a transition from highly paternalistic approaches to development (left side), to approaches that empower outgrowers to become strong players (sometimes as a group) in the sugarcane sector. However, with this autonomy comes greater risks and rewards. As farmers have greater control they also potentially access a greater proportion of the income, but also more substantial risks (e.g. in terms of financial bankruptcy and even potential loss of their land).

The y-axis indicates the type of support offered to outgrower schemes. As discussed in Section 3.2.2 the degree, type and source of support (e.g. from government, companies) differed substantially between projects. The offered support is often linked to the need to access/obtain loans to establish irrigation infrastructure. Where irrigation infrastructure is in place this typically requires some form of guarantees to the investors that needs to be underwritten by state or private sector involvement in the projects.

Dryland outgrowers are typically individual farmers that grow sugarcane on their individual land. Thus they have the greatest tenure security and management autonomy. However their profitability depends to a large extent on market and environmental conditions (e.g. rainfall) and they tend to have the lowest level of institutional support.

Extensive institutional support is a pre-condition for irrigated sugarcane farming to develop, operate and maintain the irrigation infrastructure. As a result irrigated projects tend to receive high support from the state or industry, but sometimes with very limited empowerment or autonomy in decision-making and management to outgrowers, and at a high cost that reduces their potential financial returns.

Based on the results of the comparative analysis of the different outgrower projects outlined above, some key recommendations for sugarcane projects (including possible future biofuel projects) in southern Africa include: Policies are needed to ensure substantial amounts of sugarcane is sourced from outgrower schemesFootnote8. However, when using an outgrower feedstock production model, it is important to ensure that it is established in a way that ensures that outgrower schemes fully empower the participating farmers to take ownership of the crop production process. Setting up the outgrower model will require an extensive consultative processes to ensure that the final implementation model will both guarantee sustainable/viable yields for processing plants and be in the best interests of the local communities. Further, it is critically important (to the extent possible considering the project context), that the farmers who participate in the scheme are sourced from the local community, and should be those farmers that are making their land available for the project. In cases where all current farmers cannot be incorporated in the scheme, it is paramount that adequate and just compensation is given to any landholders who are displaced during the establishment of new projects. Once established, adequate support must be provided to outgrowers from the state and/or the processing facility. It is also advisable that oversight from the state and/or NGOs is provided to ensure that the interests of the outgrowers are well protected.

4. Conclusions

The models of sugarcane outgrower schemes in southern Africa have radically different characteristics that have evolved over time and continue to evolve. In some schemes (usually dryland), outgrowers produce sugarcane individually on land to which they have traditional tenure rights. In other schemes (usually irrigated), multiple outgrowers operate as a single legal entity after land consolidation processes have occurred. The nature of these groups has changed from associations, trusts and cooperatives, to commercial enterprises owned by outgrower groups.

The mechanisms through which income and dividends were shared among outgrowers groupings differs between projects. In some projects, payments were proportional to the actual yield obtained from an individual outgrower’s allocated land within the group, whilst in others, the dividends were split equally among all group members. Early schemes tended to adopt a paternalistic approach towards development, with management decisions and responsibilities undertaken by either government run enteritis or the sugar industry with the farmers have had a very limited role in both farming and management. More recent schemes are moving toward models that empower original landholders (peasant farmers) to have the full ownership of the project, as shareholders of companies fully owned by the farmers. Such schemes allow groups of local farmers to become members of large-scale commercial sugarcane production projects where they fully own and manage the operation, outsourcing seasonal labour-intensive activities such as cultivation and harvesting. Since the original ‘landowner’ are now shareholders and not necessarily actively doing the farming, many of them have time and resources to become players in other aspects of the sugarcane value chain. However, these models are not without fault, with increased reward there is increased risks to participating farmers. Further, the long term sustainability of these model, especially when government led institutional support declines and future investment (e.g. for replanting) is required, is yet to be determined. In most likelihood adaptive management that allows evolution of the model will be required.

Considering the unequal economic and political power between the sugar industry and outgrower schemes, there is a need to establish mechanisms that can protect the latter. This includes creating structures that collectively represent outgrowers to achieve increased bargaining power. As most current outgrower schemes are located in highly impoverished rural areas with low financial and educational capacity, there is a real need for assistance from NGOs and governments to prevent outgrowers falling prey to processing plants. However, extensive government involvement might reduce the incentives of the sugar industry in supporting outgrowers. Further the long-term financial viability of government supported schemes also needs consideration. It is therefore important to ensure the stability of the institutions that are set up to support outgrowers as their collapse (e.g. Agrowane in South Africa) can precipitate the total collapse of the outgrower schemes depending on their support. In many schemes, outgrowers (and their associations) are not empowered to maintain the infrastructure upon which they depend, nor do they have the ability, or authority, to seek funding to do this. Thus several aspects should be considered during the development of assistance schemes to sugarcane outgrowers. Schemes need to continually evolve based on past successes and failures, the prevailing local socioeconomic and political context as well as emerging global trends.

Emerging institutional models (such as with SWADE and Maragra) that fully empower farmers to become true owners of complex farming operations that include both irrigation infrastructure and loans appear to overcome many of the critiques to older outgrower sugarcane production models. These models are still evolving and still have problems, but indicate possible futures for new approaches to development. It is, however, recognised that such models require long term industry and/or state support. Ongoing monitoring, evaluation and adaptive management is required to ensure that viable institutional approaches are developed that can be replicated in the future.

Supplementary_material_clean.docx

Download MS Word (33.7 KB)Acknowledgements

This research was made possible through funding from UNU-Wider and the Belmont forum project. The information provided by mill owners, plantation owners, small growers and industry representatives is greatly appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We use the term ‘outgrowers’ synonymously with ‘contract farmers’. The term is well suited to describe the typical nuclear plantation model found in sugarcane growing where there is as core estate and then the ‘outgrowers’ who supplement the production from the core estate.

2 Sugarcane is a highly perishable crop that needs to be processed as soon as possible after harvesting. In the overwhelming cases in Africa only a single mill services a sugarcane growing area (Dubb et al., Citation2017).

3 In the sugar industry the processing plant is typically referred to as a sugar mill. Sugarcane crushing to extract the sucrose rich juice is the first part of sugarcane processing (whether for sugar or ethanol). Subsequent processes include the extraction and refinement of the sugar, or the production of ethanol. Ethanol production can happen from the fermentation of either sugarcane juice or molasses, which is a by-products of sugar refinement. The more generic term “processing plant” could apply to the mill, refinery or ethanol production facility.

4 In South Africa it was found that regions tended to have a common approach and it was easier to discuss this approach in totality rather than linking it to one of the many small projects.

5 Participants in the Kaleya outgrower scheme have been sourced from throughout Zambia (Schupbach, Citation2014).

6 The %RV refers to the % recoverable value and is a mechanism to compensate growers that harvest before or after their sugarcane reaches its peak value. This allows for the extension of the harvesting period and essentially for greater seasonal throughput from the mill. By extending their operating periods, mills can therefore provide a market to a larger area of sugarcane producers.

7 It is worth mentioning that in contrast to the irrigated farmers, the dryland farmers in Dwangwa operate/negotiate directly with the processing plant through their associations which are independent of state control.

8 As shown In this study outgrower models can produce sugarcane (and other industrial crops) as efficiently as core plantations, but without some of the negative social impacts.

References

- Atkins, S, 2014. Smallholder sugarcane production in Malawi: An analysis of outgrower participation in the country’s sugar industry. Second annual ECAMA research symposium. https://www.slideshare.net/IFPRIMaSSP/smallholder-sugarcane-production-in-malawi-an-economic-analysis-of-outgrower-participation-in-the-sugar-sector accessed 5 April 2017.

- Bernstein, H, 2010. Class dynamics of agrarian change. Fernwood, Halifax; MA: Kumarian.

- Borras, SM, McMichael, P & Scoones, I, 2010. The politics of biofuels, land and agrarian change: Editors’ introduction. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37(4), 575–92. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512448

- Chinsinga, B, 2016. The green belt initiative, politics and sugar production in Malawi. Journal of Southern African Studies 43, 501–15. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1211401

- Chinsinga, B, Chasukwa, M & Zuka, SP, 2013. The political economy of land grabs in Malawi: Investigating the contribution of limphasa sugar corporation to rural development. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26(6), 1065–84. doi: 10.1007/s10806-013-9445-z

- Conigliani, C, Cuffaro, N & D’Agostino, G, 2018. Large-scale land investments and forests in Africa. Land Use Policy 75, 651–60. doi: 10.1016/J.LANDUSEPOL.2018.02.005

- Cotula, L & Leonard, R, eds, 2010. Alternatives to land acquisitions: Agricultural investment and collaborative business models. London: IIED.

- Cotula, L, Vermeulen, S, Leonard, R & Keeley, J, 2009. Land grab or development opportunity. Agricultural investment and international land deals in Africa, p.17.

- Deininger, K & Byerlee, D, 2012. The rise of large farms in land abundant countries: Do they have a future?. World Development 40(4), 701–14. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.04.030

- Dubb, A, 2015. Dynamics of decline in small-scale sugarcane production in South Africa: Evidence from two ‘rural’ wards in the umfolozi region. Land Use Policy 48(362), 362–76. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.06.029

- Dubb, A, 2016. The rise and decline of small-scale sugarcane production in South Africa: A historical perspective. Journal of Agrarian Change 16, 518–42. doi: 10.1111/joac.12107

- Dubb, A, 2017. Interrogating the logic of accumulation in the sugar sector in Southern Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 43(3), 471–99. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1219153

- Dubb, A, Scoones, I & Woodhouse, P, 2017. The political economy of sugar in Southern Africa – introduction. Journal of Southern African Studies 43(3), 447–70. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1214020

- Eaton, C & Shepherd, A, 2001. Contract farming: Partnerships for growth (No. 145). Food & Agriculture Org.

- Gasparatos, A, Von Maltitz, GP, Johnson, FX, Lee, L, Mathai, M, De Oliveira, JP & Willis, KJ, 2015. Biofuels in sub-Sahara Africa: Drivers, impacts and priority policy areas. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 45, 879–901. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.006

- Gasparatos, A, Romeu-Dalmau, C, von Maltitz, GP, Johnson, FX, Shackleton, C, Jarzebski, MP, Jumbe, C, Ochieng, C, Mudombi, S, Nyambane, A & Willis, KJ, 2018. Mechanisms and indicators for assessing the impact of biofuel feedstock production on ecosystem services. Biomass and Bioenergy 114, 157–73.

- Glover, DJ, 1984. Contract farming and smallholder outgrower schemes in less-developed countries. World Development 12(11–12), 1143–57. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(84)90008-1

- Hall, R, 2011. Land grabbing in Southern Africa: The many faces of the investor rush. Review of African Political Economy 38(128), 193–214. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2011.582753

- Hall, R, Scoones, I & Tsikata, D, 2017. Plantations, outgrowers and commercial farming in Africa: Agricultural commercialisation and implications for agrarian change. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44:3, 515–37. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1263187

- Herrmann, RT, 2017. Large-Scale agricultural investments and smallholder welfare: A comparison of wage labor and outgrower channels in Tanzania. World Development 90, 294–310. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.007

- Herrmann, R & Grote, U, 2015. Large-scale agro-industrial investments and rural poverty: Evidence from sugarcane in Malawi. Journal of African Economies 24(5), 645–76.

- Hartley, F, van Seventer, D & Samboko, P, 2017. Economy-wide implications of biofuel production in Zambia. Wider working paper 2017/27.

- Hess, TM, Sumberg, J, Biggs, T, Georgescu, M, Haro-Monteagudo, D, Jewitt, G, Ozdogan, M, Marshall, M, Thenkabail, P, Daccache, A Marin, F, & Knox, JW, 2016. A sweet deal? Sugarcane, water and agricultural transformation in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Environmental Change 39, 181–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.003

- James, P & Woodhouse, P, 2016. Crisis and differentiation among small-scale sugar cane growers in Nkomazi, South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 7070(November), 1–15. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1197694

- Landell Mills Limited, 2012. Study into land allocation and dispute resolution within the sugar sector and other EU irrigation development programmes in Malawi, Trowbridge, Wiltshire.

- Matenga, CR, 2016. Outgrowers and livelihoods: The case of magobbo smallholder block farming in mazabuka district in Zambia. Journal of Southern African Studies 43(3), 551–66. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1211402

- Matenga, CR & Hichaambwa, M, 2017. Impacts of land and agricultural commercialisation on local livelihoods in Zambia: Evidence from three models. The Journal of Peasant Studies 44(3), 574–93. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1276449

- Mhlanga-Ndlovu, BF, & Nhamo, G, 2017. An assessment of Swaziland sugarcane farmer associations’ vulnerability to climate change, Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences 14(1), 39–57. doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2017.1335329

- Mudombi, S, Von Maltitz, GP, Gasparatos, A, Romeu-Dalmau, C, Johnson, FX, Jumbe, C, Ochieng, C, Luhanga, D, Lopes, P, Balde, BS & Willis, KJ, 2016. Multi-dimensional poverty effects around operational biofuel projects in Malawi, Mozambique and Swaziland. Biomass and Bioenergy 114, 41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2016.09.003

- Munro, D, 2012. Land and capital. Journal of Australian Political Economy (70), 214–32.

- O’Laughlin, B, 2016. Consuming bodies: Health and work in the cane fields in xinavane, Mozambique. Journal of Southern African Studies 43(3), 605–23.

- Prowse, M, 2012. Contract farming in developing countries: A review. Lund: Agence Française de Développement A Savoir.

- Richardson, B, 2010. Big sugar in Southern Africa: Rural development and the perverted potential of sugar/ethanol exports. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37(4), 917–38. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512464

- Richardson-Ngwenya, P & Richardson, B, 2014. Aid for trade and African agriculture: The bittersweet case of swazi sugar. Review of African Political Economy 41(140), 201–15. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2013.872616

- Schüpbach, J, 2014. Foreign direct investment in agriculture: The impact of outgrower schemes and large-scale farm employment on economic well-being in Zambia. Zurich: vdf Hochschulverlag AG.

- Shumba, EM, Roberntz, P & Kuona, M, 2011. Assessment of sugarcane outgrower schemes for bio-fuel production in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Harare: WWF-World Wide Fund for Nature.

- Terry, A & Ogg, M, 2016. Restructuring the swazi sugar industry: The changing role and political significance of smallholders. Journal of Southern African Studies 43, 585–603. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1190520

- Terry, A & Ryder, M, 2007, November. Improving food security in Swaziland: The transition from subsistence to communally managed cash cropping. Natural Resources Forum 31(4), 263–72.

- Vermeulen, S & Cotula, L, 2010a. Over the heads of local people: Consultation, consent, and recompense in large-scale land deals for biofuels projects in Africa. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37(4), 899–916. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512463

- Vermeulen, S & Cotula, L, 2010b. Making the most of agricultural investment: A survey of business models that provide opportunities for smallholders. London: IIED.

- Vermeulen, S, Sulle, E & Fauveaud, S, 2009. Biofuels in Africa: Growing small-scale opportunities. IIED Briefing, Business Models for Sustainable Development, Nov.[www.iied.org/pubs/display.php].

- Von Maltitz, G & Stafford, W, 2011. Assessing opportunities and constraints for biofuel development in sub-Saharan Africa (Vol. 58). Bogor: CIFOR.

- Watson, HK, 2011. Potential to expand sustainable bioenergy from sugarcane in Southern Africa. Energy Policy 39(10), 5746–50. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2010.07.035

- White, B, & Dasgupta, A, 2010. Agrofuels capitalism: A view from political economy. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37(4), 593–607. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512449