ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to establish whether the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance in Uganda’s informal economy exists and whether motivation mediates the relationship. The survey was conducted in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region using a structured questionnaire. The sample included three hundred eighty-six employees of Small and Medium Enterprises. Hypotheses and mediation tests were carried out by way of structural equation modeling, using Analysis of Moment Structures and Sobel’s test respectively. Results from hypotheses’ tests indicate significant positive relationships between core values and entrepreneurial performance. Furthermore, it was established that motivation significantly mediates the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance (except trust). Based on the study’s results, it is recommended that Small and Medium Enterprises should seek to acquire skills on how to fully turn motivation into business advantage and how to use core values as tools for marketing the business.

1. Introduction and problem statement

The notion of the ‘informal economy’ was first introduced by Hart in Citation1972, who conceived informality as being associated with income generating activities which are unregistered and institutionally non-compliant. In keeping with this conceptualisation, Daniels (Citation2004) suggests that the informal economy comprises of unreported income from self-employment, wages, salaries relate to unreported goods and services, the barter of legal goods and services and sometimes trading in stolen goods. Furthermore, the informal economy comprises of workers who have neither employment contracts nor social benefits (Henley et al., Citation2009).

Despite the large survivalist nature of the informal economy, an increasing body of research has sought to establish the entrepreneurial nature of the space (see for instance Langevang et al., Citation2012; Synder, Citation2004; Williams, Citation2008, Citation2009). It is this premise that this paper proceeds such that the informal economy is inclusive of opportunity-driven entrepreneurial behaviour (Urban et al., Citation2011; Venter & Callaghan, Citation2011).

Uganda has a large informal sector contributing to a low tax to Gross Domestic Product ratio of 13%. The ratio is below the sub-Saharan rate of 26% (African Economic Outlook, Citation2012). Moreover, an International Labour Organisation Report (Citation2012) indicates that 95% of Uganda’s labour force falls in the informal economy with much of the labour provided by women (see for instance Chen, Citation2000). Furthermore, it was estimated that by 2010, of the 5.5 million Ugandan youths engaged in the labour force, 3.5 million were in the informal businesses (International Labour Organisation Report, Citation2012).

Despite the increasingly important role Small and Medium Enterprises play in job creation in developing countries such as Uganda (Randall, Citation2008), Hammann et al. (Citation2009) are of the view that these businesses do not express a value-based socially responsible orientation towards doing business formally but rather does so through the values of the owner/entrepreneur. However, little exists by way of research which considers core values of entrepreneurs within the informal economy and more specifically that of Uganda.

Furthermore, although core values motivate employees (Alas & Tuulik, Citation2005; Dahlgaard-Park, Citation2012; Katou, Citation2015; Long, Citation2016), the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance in Uganda’s informal economy has not yet been established. The immediate study to this effect was Kakeeto-Aelen et al. (Citation2014) which considered neither motivation nor entrepreneurial performance. They discussed trust in relation to customer satisfaction rather than core values and entrepreneurial performance. Therefore, this study sought to provide empirical findings and extend both literature and practical knowledge by establishing the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance within Small and Medium Enterprises in Uganda’s informal economy.

1.1. Theoretical framework

Dahlgaard-Park (Citation2012) and Katou (Citation2015) contend that core values instil commitment among workers. Furthermore, employees are motivated if they are fairly treated (Falk, Citation2014; Long, Citation2016). Kintu (Citation2017) argues that core values are not only motivators, they are also behavioural reinforcers. Behavioural reinforcement occurs where there are stimuli that cause a repeat of a behaviour or action/ performance (Skinner, Citation1938). In this case, core values are stimuli. Since core values motivate and reinforce employees’ behaviour, and motivated employees enhance firm performance (Emich & Wright, Citation2016), the study is guided by the motivational reinforcement theory.

2. Literature review

This paper provides insights into the impact that motivation has on the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance amongst informal economy workers in Uganda. In this section, different variables under investigation are explored before hypotheses are formulated and the hypothesised model is developed. The section commences with a consideration of core values, after which entrepreneurial performance is explored. Thereafter, hypothesised relationships between motivation, core values and entrepreneurial performance are discussed.

2.1. Core values

In order to shape employee behaviour, core values are basic principles to adopt (Lencioni, Citation2002). In addition, for a firm to introduce ethical culture at work, it should adopt ethical behaviour (Roberts-Lombard et al., Citation2016). Basing on this ideology, scholars such as Schwartz (Citation2005) and Schmiedel et al. (Citation2013) provide for moral/core values to guide employee behaviour in a firm. Such values include; trust, fairness, respect and responsibility. Besides these values, the qualitative study in Uganda’s informal economy by Kintu (Citation2017) established cleanliness as a value. Furthermore, businesses establish core values to guide morality and enhance ethical behaviour (Mahajan & Mahajan, Citation2016). Moreover, moral values which are right or wrong guide employee behaviour in a firm (Rakesh et al., Citation2016). Having introduced core values, it is important to consider entrepreneurial performance in the next section.

2.2. Entrepreneurial performance

It requires risk taking and innovativeness to achieve entrepreneurial performance (Lumpkin & Dess, Citation2001). Entrepreneurial performance can be measured by product diversification and market diversification (Yu, Citation2013). Furthermore, entrepreneurial performance can be measured by profits, accumulated employment and survival duration (Bosma et al., Citation2002). However, given the nature of this study, accumulated employment and product diversification were identified as measures for entrepreneurial performance because both measures do not require rigorous record keeping.

2.3. Core values and motivation

Much of the literature that exists on motivation within the informal economy considers the overall motive of the individual entrepreneur (that is, whether the entrepreneur is driven by opportunity or necessity) (see for instance Gurtoo & Williams, Citation2009), with a relative paucity of research on the motivation of informal workers. This said, broad research provides insights into the relationship between core values and motivation allowing for extrapolation to experiences of employees in the informal economy. Trust, for instance, helps employees develop positive work-related attitude and behaviour, which in turn results in great motivation and productivity levels (Rupova et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, a study by Dahlgaard-Park (Citation2012) shows that companies which do not practice core values, struggle to motivate employees. In addition, Ard (Citation2015) established that strong core values improve employee morale. Therefore, informal economy Small and Medium Enterprises in Uganda’s central region have to ensure that core values are sufficiently inclusive to motivate workers. Ard (Citation2015) agrees with Loch et al. (Citation2012)’s supposition that respect for employees improves their morale. Moreover, Falk (Citation2014) established that the fair treatment of workers motivates them. At the same time, Katou (Citation2015) indicated that trust motivates and enhances employee commitment. This finds resonance with Nakos & Brouthers (Citation2008) who contend that trust provides a foundation for commitment. It can further be observed that whereas Dahlgaard-Park (Citation2012) and Katou (Citation2015) state that values such as trust motivate employees through improved commitment, Long (Citation2016) affirms that fairness motivates employees’ work performance. Moreover, trust among workers encourages them to share ideas more openly (Emich & Wright, Citation2016). Finally, Alas & Tuulik (Citation2005) observe that if values are commonly held by both managers and subordinates alike, motivation can be easily achieved. Therefore, it is indicative that employees need to feel that they are trusted, they are working under a fair system, they are respected so as to be motivated and deliver results at the work place. The following hypothesis is formulated accordingly.

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant and positive relationship between core values and motivation among SMEs in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region.

2.4. Motivation of employees and entrepreneurial performance

The research that exists on the relationship between the motivation of employees of Small and Medium Enterprises and overall entrepreneurial performance is scanty. For the most, here, research tends to point, to the motivation of individual entrepreneur and entrepreneurial performance (see for instance Carsrud & Brannback, Citation2011). Despite this, however, literature exists linking motivation of employees to organisational performance at large. Dobre (Citation2013) for instance, observed that employee motivation is positively related to organisational performance. In addition, Ard (Citation2015) agrees with Soundarapandiyan & Ganesh (Citation2015) that once employees’ morale is enhanced, employee retention rates increase. Furthermore, Yildiz et al. (Citation2009) established that motivation was statistically significant to workers’ intention to leave the job. In addition, Mak & Sockel (Citation2001) found out that employee motivation is highly related with employees’ intentions to stay on the job. Tabassi & Abu Baker (Citation2009) contend that to improve employee innovation, employers should use workers’ participation and motivation. Therefore, Small and Medium Enterprises in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region must benefit from core values because they increase workers’ commitment to better performance (Dahlgaard-Park, Citation2012). This implies that the more employees feel energised, the more likely they will stay working for an organisation. It is thus clear that whenever employees are motivated, firm performance improves, this then leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: There is a significant and positive relationship between the motivation of employees and entrepreneurial performance among SMEs in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region.

2.5. Core values and entrepreneurial performance

Finally, it is fair to conclude, that, given the lack of research on values in the informal economy as reflected on earlier in this paper, scanty literature equally exists, therefore, to relate values to entrepreneurial performance in this space. Once more, broad literature is considered to establish potential relationships. For instance, if the reward system is seemingly unfair among employees, they can relax in meeting job demands (Janssen, Citation2000). In addition, promoting fairness at work helps to increase productivity (Long, Citation2016). Though Long (Citation2016)’s assertion about productivity is from a fairness side of view, he concurs with Jing et al. (Citation2014) who established that high levels of trust between managers and employees enhance productivity. Furthermore, Roberts-Lombard et al. (Citation2016) contend that a proper code of ethics improves business performance. Since Small and Medium Enterprises in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region employ people from different cultural orientations to perform tasks in business operations, Roberts-Lombard et al. (Citation2016)’s argument is important for consideration by managers of these Small and Medium Enterprises. Furthermore, core values can make firms attractive to potential employees (Chong, Citation2009). In addition, Coldwell et al. (Citation2008) observe that for workers to stay longer on the job, their values should be matching the employer’s values. Moreover, some employees need responsibility to feel they are good enough in a firm. Therefore, assigning workers responsibility is one way of motivating them to stay on the job (Idris, Citation2014). It is also important to know that firms which have good links and trust with stakeholders engage in better ways of product/or service diversification (Slack, Citation2015; Su & Tsang, Citation2015). In addition, firms that act ethically can ably differentiate their products and increase demand (Brickley et al., Citation2002). Furthermore, it is recognisable that businesses that hub ethical behaviour improve their performance (Hitt & Collins, Citation2007). Therefore, it is worth understanding that core values which are a major component of organisational culture play a major role in enhancing entrepreneurial performance. The following hypothesis is thus stated;

Hypothesis 3: There is a significant and positive relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance in SMEs in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region.

2.6. The mediating effect of motivation

Dobre (Citation2013) contend that employee motivation positively affects firm performance, but motivation is enhanced by values (Parks & Guay, Citation2009). Moreover, trust causes motivation, and motivation results in firm productivity (Rupova et al., Citation2015). In the same way, Katou (Citation2015) believes that trust increases staff motivation hence increased firm performance. Since core values improve employees’ motivation, and that motivation results in firm performance, it is important for Small and Medium Enterprises in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region to ensure that the core values crafted are motivational enough to enhance Small and Medium Enterprises performance.

Furthermore, Aryee et al. (Citation2015) established that intrinsic motivation significantly mediates the relationship between trust and job performance. Although the performance variable in this study was not entrepreneurial, it indicates that motivation can mediate the relationship which involves a core value component. In addition, Joo et al. (Citation2010) provide that intrinsic motivation can mediate the relationship between employee responsibility (job autonomy) and role-job performance. This position highlights, however, that there is limited literature which focuses on the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance.

The discussion provided above indicates that motivation can mediate the relationship between core values and any other variables. However, in this case, scholars have concentrated on other factors rather than entrepreneurial performance. Since limited literature exists which explores the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance, this justified the study’s relevance. The following hypothesis is stated:

Hypothesis 4: Motivation mediates the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance of SMEs in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region.

3. Methods

Given the nature and purpose of the study, a quantitative approach was employed. Because of informality and associated complexities of drawing an accurate sampling frame, due for instance, to churn between the informal and formal economies (see, for instance, Devey et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b), a convenience sampling technique was adopted. The sample size was 386 respondents conducted in the towns of Masaka, Mityana, Kampala, Wakiso and Mukono. The sectors considered for the study were supermarkets, hair dressing salons, cosmetic processing, juice processing and restaurants. The sectors are considered for this study because the establishment of informal workers is common in these sectors (Uganda Investment Authority and Ernst & Young, Citation2011). In addition, the selected study area is the most urbanised in Uganda (Uganda Investment Authority and Ernst & Young, Citation2011). Furthermore, data were collected through a questionnaire using a five-point Likert scale. On the scale, cumulative employment was measured by; firm’s ability to retain current employees because of a fair payment system, firm’s ability to retain current employees because commissions are determined fairly and firm’s ability to retain current employees because of attractive premises. On the other hand, product diversification was measured by firm’s products penetrating markets because of trust, employees’ ability to introduce a variety of new products/services because of trust and customers perceive a variety of firm products/ services are superior over competitors. In addition, the Small and Medium Enterprises considered for analysis were those which had operated for at least three years and employ five and more workers. Collecting data from employees of those Small and Medium Enterprises would ensure consistency. Reliability for the questionnaire was determined by Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability scores. The Average Variant Extracted (AVE) was used to measure convergent validity and AVE is acceptable at a level of ≥0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Farrell & Rudd, Citation2009). For the discriminant validity, Fornell & Larcker (Citation1981), Li et al. (Citation2017) emphasise that it exists when the Average Variant Extracted scores of two factors are higher than the square of the correlation between the two factors. In this study, the researcher compared the Average Variant Extracted scores with the square of correlation among the latent variables to determine whether constructs are not closely related or whether they are not measuring the same aspects. The Likert scale measured responses along negative to positive where expected responses were; strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree and strongly agree (Likert, Citation1932). Research assistants were recruited to undertake the exercise. Each research assistant signed an agreement to undertake the exercise and to keep information confidential. The study exposed research assistants neither to physical risks nor to emotional dangers. Secondary data was collected from the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports and the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development. The data from secondary sources helped substantiate already existing data with the primary data collected. Furthermore, secondary data assisted in providing comparative information for future decision making, especially policy about Small and Medium Enterprises in the informal economy.

Data were analysed by way of structure equation modelling (SEM). SEM can help test and analyse network relationships between variables (Suhr, Citation2009). Furthermore, SEM is a powerful tool for analysis (MacCallum & Austin, Citation2000). For the purpose of this study, SEM was used to analyse latent variables; core values, motivation and entrepreneurial performance. The measured variables were: trust, fairness; respect, responsibility, cleanliness, product diversification and cumulative employment. The study further complied with the SEM condition of adhering to a large sample size of 200 and above (Hussey & Eagan, Citation2006). Furthermore, the measurement model was established to estimate the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This is because the CFA is better handled under SEM (Ullman, Citation2006). The model fit was tested by chi-square which should be <3, CFI = 0–1, GFI tending to 1, AGFI, >0.9 and RMSR tending to 0 (Guha, Citation2010). The model was well estimated and identified by Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS). Furthermore, the model specification was done following literature review and research hypotheses (Urbach & Ahlemann, Citation2010).

Finally, in order to test for mediation, soft and hard tests were used. Mediation exists when the independent variable affects the dependent variable indirectly through at least one intervening variable (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). In addition, Baron & Kenny (Citation1986) and Beaujean (Citation2011) provide three conditions which must be fulfilled; i) the independent variable has to be significantly related to the mediating variable, ii) the independent variable has to be significantly related to the outcome variable and iii) the magnitude of the relationship between the independent and the outcome variables must significantly decrease after controlling for the mediating variable. Moreover, Sobel’s (Citation1982) test was used as a hard measure for mediation. Sobel test determines the significance of the indirect effect by testing the hypothesis of no difference between total effect (c) and direct effect ć (Totawar & Nambudiri, Citation2014). The decision rule in determining whether a variable is indeed a mediator under Sobel’s test is; the P-value must not exceed .05 (Totawar & Nambudiri, Citation2014). For the purpose of this study, Sobel’s test for mediation was used to determine whether motivation mediates the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance.

4. Research findings

The study findings indicate that more females are engaged in informal work than males. Female respondents represented 58.29% while males represented 41.71%. It is observed that more than half of the respondents were female. This implies that overall, females are more willing to work in the informal economy compared to males. This position is supported by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (Citation2015) that 51% of the youth labour force in Uganda is constituted by females. At the same time, the more representation of females compared to males in this study may imply that females are more trusted at work than their male colleagues. Another reason perhaps to explain this phenomenon is that commissions and pay in the informal economy are very low; men have many responsibilities that the pay offered in this sector may not be sufficient to cover all their needs (Kintu, Citation2017). Other respondents were of a view that men dislike such small informal jobs, therefore, they have a bad mindset about jobs offered in the informal economy. Furthermore, husbands cannot provide all what their wives need. Consequently, the wives end up working in the informal economy to supplement what their husbands can provide.

The reliability scores indicate an overall Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.91 which implies that the questionnaire was reliable. The breakdown of the components indicates that the motivation is α = 0.726. This represents good reliability scores. To test the reliability of the instrument, composite reliability (CR) was calculated. The CR for core values is 0.93, that of motivation is 0.82 and entrepreneurial performance is 0.698. This indicates that the measuring instrument is reliable. The Average Variant Extracted (AVE) was used to measure convergent validity. The AVE scores for core values indicate AVE = 0.497, motivation indicates AVE = 0.61 and entrepreneurial performance indicates AVE = 0.55. In addition, in order to determine that latent variables are not measuring the same items, discriminant validity was tested by determining the square of correlations between the latent variables. The square of correlations between core values and motivation is 0.49, that of motivation and entrepreneurial performance is 0.26 and that of core values and entrepreneurial performance is 0.50. These values are below the AVE scores; therefore, the latent variables in the study do not measure the same aspects.

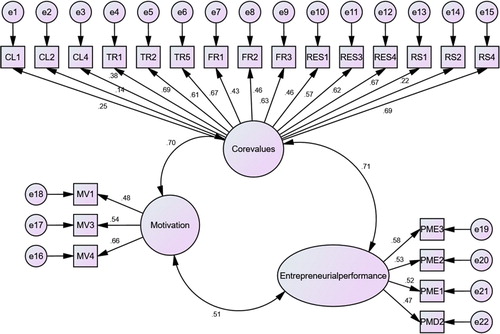

Using the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), further analysis was carried out. The measurement model is presented in .

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis for core values, motivation and entrepreneurial performance. Key: MV is motivation; FR is fairness; PME is Cumulative employment; CL is cleanliness; RES is responsibility; PMD is product diversification; TR is trust; RS is respect.

The results presented in indicate that chi-square is significant at P = .00, the degree of freedom of 206 and CMIN/DF of 4.678. The AGFI is 0.781, GFI is 0.821, RMR is 0.086 and CFI 0.691. Furthermore, the covariances indicate significant relationships and results are indicated in .

Table 1. Covariances and significance levels of study variables.

The analysis in was conducted for the purpose of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis. The variables are related since all the P-values are significant. However, since covariance cannot reveal which variable is more influential in explaining entrepreneurial performance, further analysis was conducted by way of regression as indicates.

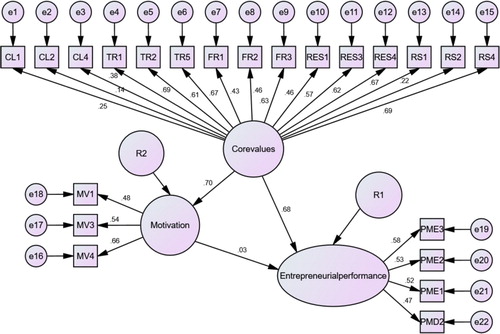

Figure 2. Hypothesis testing for the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance. Key: MV is motivation; TR is trust; PME is cumulative employment; CL is cleanliness; RES is responsibility; PMD is product diversification; FR is fairness; RS is respect.

From the regression analysis performed in , the chi-square is significant at P = .00, the degree of freedom of 206 and CMIN/DF of 4.678. The AGFI is 0.781, GFI is 0.821, RMR is 0.086 and CFI 0.691. Furthermore, the regression indicates significant relationships except for the relationship between motivation and entrepreneurial performance and more results are provided in .

Table 2. Statistics summery of the specified model.

indicates that the relationship between core values and motivation is positive and significant and the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance is positive and significant. This implies that hypotheses (H1 and H3) are supported whereas H2 is not supported. Furthermore, it is established that core values significantly influence entrepreneurial performance. This is to the extent of 68%. On the other hand, motivation insignificantly influence entrepreneurial performance to the extent of 3%.

Since core values motivate employees and at the same time influence entrepreneurial performance, it is important to determine whether the motivation generated from core values can influence the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance. The mediation effect was determined using the Sobel test. The results are presented in .

Table 3. Sobel test results for mediation effect.

The results in indicate that motivation does not mediate any relationship where trust is an independent variable. However, motivation mediates the relationships between; cleanliness and product diversification, cleanliness and cumulative employment, fairness and product diversification, fairness and cumulative employment, responsibility and cumulative employment, respect and product diversification, and respect and cumulative employment. Therefore, the significance of the statistics implies that hypothesis 4 is supported. This is to say that motivation significantly mediates the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance in Small and Medium Enterprises in Uganda’s central region.

5. Discussion

Having set the hypothesis and presented study findings, this section discusses the findings in relation to study questions and hypotheses. The model presented in indicates a positive regression weight of 0.7 for the first hypothesis. Furthermore, the relationship is strong and significant, implying that core values strongly determine employee motivation in Small and Medium Enterprises in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region. The study findings are in agreement with Dahlgaard-Park (Citation2012) who established that core values instil commitment among employees. In addition, Rupova et al. (Citation2015) and Katou (Citation2015) assert that trust in a firm develops employees’ good attitude. At the same time, Ard (Citation2015) found out that core values improve employees’ morale. It is very important therefore for managers to ensure that employees adhere to core values.

Having discussed core values and motivation, the second hypothesis relates to motivation and entrepreneurial performance. The results from the model in indicate a positive regression weight of 0.03, but the relationship is insignificant. The study, therefore, deviates from findings of Ard (Citation2015) who established that motivation significantly relates to employee retention. At the same time, the study’s findings differ from Dobre (Citation2013) who found out that motivation significantly relates to firm performance. It is, therefore, important to state that although employees in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region are motivated by core values, the level to which supervisors or managers harness employee motivation for entrepreneurial performance is insignificant.

Furthermore, the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance was investigated under the third hypothesis. Results from indicate a significant positive regression weight of 0.68. This implies that in the informal economy in Uganda’s central region, employees and other stakeholders care about core values in order to create more employment and provide more products and services. The study findings further agree with scholars such as; Long (Citation2016) and Roberts-Lombard et al. (Citation2016) who established that fairness improves firm productivity and proper code of ethics improve firm performance respectively. Furthermore, the study findings agree with Chong (Citation2009) who asserts that core values make a firm attractive to potential employees. In addition, Idris (Citation2014) observed that responsibility assigned to workers motivates them to stay on the job. At the same time, Slack (Citation2015); Su & Tsang (Citation2015) found core values to be a major factor for product diversification. This is all in support of the study findings.

In order to understand the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance, the fourth hypothesis was tested. In this case, the Sobel test results indicate significant relationships in the paths of core values, motivation and entrepreneurial performance as indicates. However, it is indicated that motivation does not mediate any relationship where trust is the independent variable. This may imply that many Ugandan entrepreneurs are not trusted. Therefore, many employees are sceptical about supervisors’ or business owners’ intentions or promises. On the other hand, findings for other components of core values agree with Aryee et al. (Citation2015) who observed that intrinsic motivation mediates the relationship between core values and job performance. At the same time, Parks & Guay (Citation2009) confirmed that motivation enhanced by core values influences firm performance. The study confirms that motivation does not only mediate the relationship between core values (except trust) and job performance, it also mediates the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance especially in the informal economy of a developing country such as Uganda.

6. Conclusion

It has been well established that core values significantly influence entrepreneurial performance. This is in agreement with earlier scholars such as Long (Citation2016), Chong (Citation2009) and Idris (Citation2014). Furthermore, the study intended to establish the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance. It has been established that motivation can significantly mediate the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance. However, the study’s findings indicate that motivation cannot mediate the relationship between trust and entrepreneurial performance. This presents a situation of scepticism between entrepreneurs or supervisors with employees in Small and Medium Enterprises in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region. In addition, whereas literature from authors such as Katou (Citation2015), Dahlgaard-Park (Citation2012) and Ard (Citation2015) argue that motivation significantly influences firm performance, employee attraction or product diversification, the informal economy of Uganda’s central region presents another framework where motivation cannot significantly influence entrepreneurial performance. Supervisors should practice trust and emphasise trust among employees to motivate them to perform. This is a cheaper means of energising people to perform better since it’s a non-monetary tool.

Whereas the study was conducted in Uganda’s central region, its findings can be generalised for whole Uganda. The sample size of 386 is adequate and the central region is Uganda’s most urbanised region (Uganda Investment Authority and Ernst & Young, Citation2011).

In order to emphasise skilling workers, the National Council for Higher Education together with the Ministry of Education should ensure that before accrediting any programme to be rolled out in institutions, soft skills have to be prioritised. Having conducted this study in an informal economy in service sectors, the researchers recommend more studies to be undertaken in the agriculture sector.

7. Scientific contribution

There is a dearth of literature pertaining to the mediating effect of motivation on the relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance. Moreover, little exists by way of research relating to entrepreneurial behaviour in Uganda’s informal economy. Aryee et al. (Citation2015) for instance established the mediating effect of motivation on the relationship between fairness and job performance. However, this study established a significant mediating effect of motivation in the relationship between core values except trust and entrepreneurial performance in addition to establishing an insignificant relationship between motivation and entrepreneurial performance in Uganda’s informal economy.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Makerere University and DAAD for providing the necessary support and resources to facilitate the completion of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- African Economic Outlook, 2012. Report on Uganda’s economic performance. www.africaneconomicoutlook.org Accessed 17 February 2018.

- Alas, R & Tuulik, K, 2005. Ethical values and commitment in Estonian companies. Estonian Business Review 19, 73–83.

- Ard, G, 2015. Culture-can happiness lead to money? Reeves Journal 95(5), 14–5.

- Aryee, S, Walumbwa, FO, Mondejar, R & Chu, CLW, 2015. Accounting for influence of overall justice on job performance: Integrating self-determination and social exchange theories. Journal of Management Studies 52(2), 231–52.

- Baron, MR & Kenny, AD, 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51(6), 1173–82.

- Beaujean, AA, 2011. Mediation, moderation and the study of individual differences in best practices in quantitative methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Bosma, N, Van Praag, M, & Wit, G, 2002. Entrepreneurial venture performance and initial capital constraints; an empirical analysis. Netherlands, Zoetermeer (Business & Policy Research). www.eim.nl/smes-and-entrepreneurship/ Accessed 28 March 2017.

- Brickley, AJ, Smith, CW & Zimmerman, JL, 2002. Business ethics and organisational architecture. Journal of Banking and Finance 26, 1821–35.

- Carsrud, A & Brannback, M, 2011. Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Businesses Management 49(1), 9–26.

- Chen, MA, 2000. Women and informality: A global picture, the global movement. SAIS Review 21(1), 71–82.

- Chong, M, 2009. Employee participation in corporate social responsibility and corporate identity: Insights from a disaster-response program in the Asia-Pacific. Corporate Reputation Review 12(2), 106–19.

- Coldwell, AD, Billsberry, J, Van Meurs, N & Marsh, JP, 2008. The effect of person-organisation ethical fit on employee attraction and retention: Towards a testable explanatory model. Journal of Business Ethics 78, 611–22.

- Dahlgaard-Park, SM, 2012. Core value- the entrance to human satisfaction and commitment. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence 23(2), 125–40.

- Daniels, PW, 2004. Urban challenges: The formal and informal economies in mega cities. Journal of Cities 21(6), 501–11.

- Devey, R, Skinner, C & Valodia, I. 2006a. Definitions, data and the informal economy in South Africa: A critical analysis. In Padayachee, V (Ed.), The development decade? Economic and social change in South Africa, 1994–2004. HSRC Press, Pretoria.

- Devey, R., Skinner, C., & Valodia, I., 2006b. The state of informal economy. In Buhlungu, S, Daniel, J, Southall, R, and Lutchman, J. State of Nations: South Africa 2005–2006. HSRC Press, Cape Town, pp. 223–47.

- Dobre, OI, 2013. Employee motivation and organisational performance. Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research 5(1), 53–60.

- Emich, JK & Wright, AT, 2016. The ‘I’s in team: The importance of individual members to team success. Organisational Dynamics 45(2), 2–10.

- Falk, A, 2014. Fairness and motivation. Iza World of Labour 9, 1–10.

- Farrell, AM & Rudd, JM, 2009. Factor analysis and discriminate validity: A brief review of some practical issues. http://www.duplication.net.au/ANZMAC09/papers/ANZMAC2009-389 Accessed 13 February 2018.

- Fornell, C & Larcker, DF, 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. American Marketing Association 18(1), 39–50.

- Guha, AB, 2010. Motivators and hygiene factors of generation X and generation Y: The test of two-factor theory. The XIMB Journal of Management 7(2), 122–32.

- Gurtoo, A & Williams, CC, 2009. Entrepreneurship and the informal sector: Some lessons from India. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 10(1), 55–62.

- Hamman, EM, Habisch, A & Pechlaner, H, 2009. Values that create value: Socially responsible business practices in SMEs- empirical evidence from German companies. Business Ethics, European Review 18(1), 37–51.

- Hart, K, 1972. Employment, incomes and equality: A strategy for increasing productive employment in Kenya. International Labour Organisation, Geneva.

- Henley, A, Arabsheibani, GR & Carneiro, FG, 2009. On defining and measuring the informal sector: Evidence from Brazil. World Development 37(5), 992–1003.

- Hitt, AM & Collins, DJ, 2007. Business ethics, strategy decision making and firm performance. Business Horizon 50, 353–57.

- Hussey, MD & Eagan, PD, 2006. Using structural equation modeling to test environmental performance in small and medium size manufacturers: Can SEM help SMEs? Journal of Cleaner Production 15, 303–12.

- Idris, A, 2014. Flexible working as an employee retention strategy in developing countries. Journal of Management Research 14(2), 71–86.

- International Labour Organisation Report, 2012. Decent work country program 2013–2017. www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/program/dwcp/download/uganda Accessed 13 May 2017.

- Janssen, O, 2000. Job demands, preparations of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology 73, 287–302.

- Jing, FF, Avery, GC & Bergsteiner, H, 2014. Enhancing multiple dimensions of performance in small professional firms through leader-follower trust. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 52(3), 351–69.

- Joo, BK, Jeung, CW & Yoon, HJ, 2010. Investigating the influences of core-self evaluation, job autonomy and intrinsic motivation on in-role job performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly 21(4), 353–71.

- Kakeeto-Aelen, TN, Dalen, JC, Herik, JD & Walle, B, 2014. Building customer loyalty among SMEs in Uganda: The role of customer satisfaction, trust and commitment. Maastricht School of Management, Working paper No. 2014/06. www.msm.nl.

- Katou, AA, 2015. Transformational leadership and organisational performance. Employee Relations 37(3), 329–53.

- Kintu, I, 2017. The relationship between core values and entrepreneurial performance: A study of SMEs in the informal economy of Uganda’s central region. PHD Thesis, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Langevang, T, Namatovu, R & Dawa, S, 2012. Beyond necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: Motivation and aspirations of young entrepreneurs in Uganda. International Development Planning Review 34(4), 439–59.

- Lencioni, PM, 2002. Mean something: The best of intentions. Harvard Business Review. https://services.hbsp.harvard.edu/services/proxy/content/22467537/23104631/269dda93bf3f9523a36bd9a341b943c6.

- Li, H, Zhang, Y & Li, F, 2017. Psychometric properties of the multi- affected indicator in a Chinese worker sample. Psychological Reports 120(1), 179–88.

- Likert, R, 1932. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology 22(140), 5–55.

- Loch, CH, Sting, FJ, Huchzermeier, A & Decker, C, 2012. Finding the profit in fairness. Harvard Business Review 90(10), 111–115.

- Long, CP, 2016. Mapping the main roads to fairness: Examining the managerial context of fairness promotion. Journal of Business Ethics 137(4), 757–83.

- Lumpkin, GT & Dess, GG, 2001. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry cycle. Journal of Business Venturing 16(5), 429–51.

- MacCallum, CR & Austin, JT, 2000. Application of structural equations modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology 51(1), 201–26.

- Mahajan, A & Mahajan, A, 2016. Code of ethics among Indian business firms: A cross-sectional analysis of its incidence, role and compliance. Paradigm 20(1), 14–35.

- Mak, BL & Sockel, H, 2001. A confirmatory factor analysis of IS employee motivation and retention. Information and Management 38(5), 265–76.

- Nakos, G & Brouthers, DK, 2008. International alliance commitment and performance of small and medium-size enterprises: The mediating role of process control. Journal of International Management 14, 124–37.

- Parks, L & Guay, RP, 2009. Personality, values and motivation. Personality and Individual Differences 47(7), 675–84.

- Preacher, JK & Hayes, AF, 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behaviour Research Methods 40(3), 879–91.

- Rakesh, R, Anusha, D & Suresh, A, 2016. A study on the impact of ethics in Indian business scenario. Journal of Economic Development, Management, IT, Finance and Marketing 8(2), 54–65.

- Randall, S, 2008. Investing in small and medium enterprises in Uganda. Business Development Network. Bid equity services. www.bidnetwork.org Accessed 17 March 2018.

- Roberts-Lombard, M, Mpinganjira, M, Wood, G & Svensson, G, 2016. A construct of code effectiveness: Empirical findings and measurement properties. African Journal of Business Ethics 10(1), 19–35.

- Rupova, P, Bittnerova, D & Fisher, E, 2015. The second mouse gets the cheese- A fresh look at how to improve performance at work through effective trust building. Business and Economic Research 5(1), 79–96.

- Schmiedel, T, Brocke, JV & Recker, J, 2013. Which cultural values matter to business process management? results from a global Delphi study. Business Process Management Journal 19(2), 292–317.

- Schwartz, MS, 2005. Universal moral values for corporate codes of ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 59(1), 27–44.

- Skinner, BF, 1938. The behavior of organisms: An experiment analysis. Appleton-century, New York.

- Slack, E, 2015. The bakers’ baker. Food and Drink International, pp. 134–136. www.fooddrink-magazine.com Accessed 15 December 2016.

- Snyder, K, 2004. Routes to the informal economy New York’s east village: Crisis, economics and identity. Sociological Perspectives 47(2), 215–40.

- Sobel, ME, 1982. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology 13, 290–312.

- Soundarapandiyan, K & Ganesh, M, 2015. Employee retention strategy with reference to Chennai based IT industry-an empirical study. Sona Global Management Review 9(2), 1–13.

- Su, W & Tsang, EWK, 2015. Product diversification and financial performance: The moderating role of secondary stakeholders. Academy of Management Journal 58(4), 1128–48.

- Suhr, D, 2009. The basics of structural equation modeling. http://www.lexjansen.com/wuss/2006/tutorials/tut-suhr.pdf Accessed 20 March 2018.

- Tabassi, AA & Abu Baker, AH, 2009. Training, motivation and performance: The case of human resource management in construction projects in Mashhad, Iran. International Journal of Project Management 27(5), 471–80.

- Totawar, A & Nambudiri, R, 2014. Can fairness explain satisfaction? Mediation of quality of work life in the influence of organisational justice on job satisfaction. South Asian Journal of Management 21(2), 101–22.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2015. Statistical abstract. www.ubos.org Accessed 10 February 2018.

- Uganda Investment Authority and Ernst & Young, 2011. Baseline survey of small and medium enterprises in Uganda. Final report. www.uia.org. Accessed 18 May 2016.

- Ullman, BJ, 2006. Structural equation modeling: Reviewing the basics and moving forward. Journal of Personality Assessment 87(1), 35–50.

- Urbach, N & Ahlemann, F, 2010. Structural equation modeling in information system research using Partial least Squares. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application 11(2), 5–40.

- Urban, B, Venter, R & Shaw, G, 2011. Empirical evidence on opportunity recognition behaviours of informal traders. African Journal of Business Management 5(24), 10080–91.

- Venter, R & Callaghan, C, 2011. An investigation of entrepreneurial orientation, context and entrepreneurial performance of inner-city Johannesburg street traders. Southern African Business Review 15(1), 28–48.

- Williams, C, 2008. Beyond ideal-type depictions of entrepreneurship: Some lessons learned from the services sector in England. The Service Industries Journal 28(7), 1041–53.

- Williams, C, 2009. The motives off-the-books entrepreneurs: Necessity-or opportunity-drive? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 5(2), 203–17.

- Yildiz, Z, Ayhan, S & Erdogmus, S, 2009. The impact of nurses’ motivation to work, job satisfaction, and social demographic characteristics on intention to quit their current job: An empirical study in Turkey. Applied Nursing Research 22(2), 113–8.

- Yu, MC, 2013. The influence of high performance human resource practices on entrepreneurial performance: The perspective of entrepreneurial theory. International Journal of Organisational Innovation 6(1), 15–136.