?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We use data from the ten percent sample of the 2011 Census to explore labour market outcomes among immigrants and locals in South Africa. We show that naturalised immigrants and foreigners engage more successfully with the labour market than locals on average. The ability to access social networks improves labour market access for immigrants, but sequentially controlling for observable characteristics, including networks and location, decreases immigrants’ participation and employment advantage over locals. The conditional immigrant earnings gap is negative, but because immigrants typically work in low quality jobs, their relative earnings disadvantage is entirely explained by differences in workers’ occupations and industries. Our attempts to control for the possible endogeneity of immigrant status suggest that the direction of selection bias may be different for naturalised and foreign immigrants in South Africa, reinforcing the importance of distinguishing between different immigrant groups in research of this nature.

1. Introduction

As Africa’s most advanced economy, post-apartheid South Africa (SA) is a prime destination for individuals seeking better employment prospects or fleeing abuses in their countries of birth, particularly for those from within Africa. The 2011 South African Census indicates that approximately 2.3 million people live but were not born in SA, and more than 70 percent of these immigrants are from within Africa (StatsSA, Citation2016). While many immigrants uproot to seek opportunities and a better life, the post-apartheid South African labour market is characterised by a number of challenges which both immigrants and locals must confront. Rising labour market participation, but limited employment generation, has seen unemployment rates soar, particularly among the youth (those aged 15–34). In the first quarter of 2018, the official unemployment rate was 26.7 percent, while amongst the youth this rate exceeded 52 percent (StatsSA, Citation2018).

Tensions around growing unemployment and limited job growth, coupled with intermittent spates of xenophobic violence, have brought to the fore issues around the labour market status and perceived labour market success of immigrants in SA (Adepoju, Citation2003; Adjai & Lazaridis, Citation2013). According to Crush & Pendleton (Citation2004:1) ‘xenophobia undermines social cohesion, peaceful co-existence, good governance and human rights observance’ and is a barrier to regional cooperation and harmony in the SADC region. The perception that immigrants ‘take’ South Africans’ jobs, and present ‘an obstacle to economic integration for the African majority who anticipated gains in employment and living standards after the demise of apartheid’ (Zuberi & Sibanda, Citation2004) is cited among the key reasons for xenophobic attacks (Karimi, Citation2015). Some locals are also concerned that African immigration specifically perpetuates SA’s struggles with disease like HIV/AIDS and crime (Kotze & Hill, Citation1997; Sinclair, Citation1999; McDonald et al., Citation2000; Adepoju, Citation2003).

This paper considers the labour market and employment status of working age immigrants, together with income from employment, and compares these measures to those of South Africans. The study questions whether there is cause to believe that immigrants are advantaged in the labour market compared to South Africans.

We first distinguish between native South Africans (locals), naturalised immigrants and foreign immigrants, and use data from the ten percent sample of the 2011 Census to contrast immigrants’ and locals’ characteristics. Second, we estimate the probability of labour market participation and employment for immigrants and locals. We consider not only raw differences in the probabilities of participation and employment, but also estimate probabilities conditional on observable characteristics, including social networks and municipal location. Third, we compare the returns to work between immigrants and locals. Finally, we attempt to address the influence of unobservable differences between the groups.

Our initial econometric results suggest that although immigrants in SA have a higher probability of labour market participation and employment than locals, immigrants do not fare as well in the labour market as locals in terms of earnings. The raw probability of both labour market participation and employment is higher for both naturalised immigrants and foreigners as compared to locals. Sequentially controlling for various observable differences between the groups, and including a proxy for access to social networks, reduces the estimated differences, although these remain positive. Part of immigrants’ advantage in the labour market is therefore explained by their links to social networks.

Our analysis of the returns to work reveals that incomes for both immigrant groups in SA are significantly lower than for locals once we account for selected observable differences between the employed groups. Employed immigrants in SA are more likely than locals to be self-employed (or to combine self-employment with wage employment) and to work in the informal sector or private households. This work is widely recognised as being survivalist and precarious, offering little remuneration, and employed immigrants have lower incomes than locals. Accordingly, when we account for differences in occupation, industry, type of work and sector of employment, the immigrant earnings disadvantage is eliminated.

The final part of our study recognises that immigrants may have different unobservable motives for entering SA, and could be positively or negatively selected into the labour market. We address this in two ways. First, following Peters and Sundaram (Citation2015), we restrict our estimating sample to include immigrants and internal domestic migrants only. If immigrants are a positively selected subsample, then internal domestic migrants are a preferred comparison group as they may also be positively selected on labour market characteristics. Second, we use individual-level variables and macroeconomic variables to instrument for the endogeneity of immigrant status.

Restricting our sample to migrants only does not change our overall finding of a significant participation and employment advantage, and income disadvantage, for both immigrant groups relative to locals. The instrumental variable (IV) analysis provides evidence of positive selection for naturalised immigrants: their advantage in participation and employment is reversed in the IV analysis. For foreigners, however, the IV results are suggestive of negative selection – the participation and employment advantage increases, and foreigners’ earnings advantage also increases. These results demonstrate the importance of distinguishing between immigrant groups in the South African context and suggest that it may be inaccurate to regard the immigrant population as comprising a wholly favourably selected subsample of individuals from their birth countries. Our results that attempt to control for selection should be treated as suggestive rather than conclusive, however, given the challenges of identifying appropriate instruments in the data utilised.

The paper is structured as follows: we provide a brief literature overview in section 2, and describe the data used and discuss descriptive statistics in section 3. Section 4 presents the econometric model that we estimate for participation, employment and the returns to work and we discuss our findings. Section 5 accounts for selection into immigrant status, and section 6 concludes.

2. Literature in brief

Internationally, the literature on the labour market effects of immigration is extensive: research considering the integration of immigrants and the consequences of immigration for locals spans more than five decades (overviews are provided by Borjas (Citation1994; Citation1999), Chiswick (Citation1993) and Dustmann & Glitz (Citation2005)). In addition to considering the effects of immigration on native employment and earnings, and to exploring the impact of changes in the composition of immigrant populations, the challenges faced by immigrants have also been researched in international studies, with the effect of language assimilation problems receiving significant attention (e.g. Dustmann & Van Soest, Citation2002; Chiswick & Miller, Citation2003; Dustmann & Fabbri, Citation2003).

In SA, peer-reviewed research on the economic impact of immigration is limited. Zuberi & Sibanda (Citation2004) investigate the relationship between migration status, nativity and labour force outcomes in the post-apartheid labour market for males using the 1996 Census. They show that immigrants are more likely to participate in the labour force and to be gainfully employed than the indigenous population. Peters & Sundaram (Citation2015) use 2001 Census data to estimate the probability of employment for working age immigrant men and South African internal migrants. They explore differences in participation and employment probabilities across 24 birth-country categories and show that immigrants from advanced countries perform better than nationals while immigrants from less-advanced countries perform worse than nationals.

In addition, the Migrating for Work Research Consortium (MiWorc) authored six reports on foreign labour in SA that consider the availability of existing data, suggestions for a Quarterly Labour Force (QLFS) module and municipal level survey, and statistical and econometric analysis of the data obtained from the migration module piloted in the third QLFS undertaken by StatsSA in 2012.

Distinguishing between domestic non-migrants, domestic permanent migrants and international migrants, MiWorc’s econometric analysis shows that international migrants have a higher probability of employment, and a higher probability of working in informal and precarious activities than domestic non-migrants and domestic permanent migrants (Fauvelle-Aymar, Citation2014).

A key concern with the SA research is that these studies do not control for the effect of social networks on immigrants’ labour market outcomes. Since the 1950s, the importance of networks of friends, relatives and acquaintances in providing referrals for job searchers seeking employment has been widely documented in the economics literature (Montgomery Citation1991). For immigrants, ‘ties of kinship or friendship that provide connections to jobs, people and resources at potential areas of destination’ (Neumann & Massey, Citation1994:1) may streamline the process of immigrating to any country and increase the likelihood of labour market success, particularly if social networks facilitate the acquisition of information about immigration processes, available housing and employment opportunities. Some support for this is provided by Munshi (Citation2003), who investigates labour market outcomes for individuals belonging to multiple-origin communities in Mexico using panel data comprising information on individual’s location decisions and labour market outcomes. Measuring each community’s network as a proportion of the sampled individuals who are located at the destination (the US) in any year, a Mexican migrant in the US labour market is more likely to be employed and more likely to work in a (higher paying) non-agricultural job when their network is exogenously larger.

Given the high costs of job search in SA, coupled with the expense of formal recruitment procedures and concerns over educational quality, recognising the importance of word-of-mouth as a form of passive job search and an informal recruitment channel for firms is essential. Approximately half of employed individuals in SA find their jobs through such methods (Posel et al., Citation2014). Because it is impossible to measure directly the sorts of networks that facilitate such information sharing using Census data, we adapt Bertrand et al. (Citation2000)’s method, and construct three proxy variables for social networks that encapsulate the size and quality of networks that citizens and immigrants may access. By including these controls, we recognise that social networks associated with the concentration of immigrants from similar backgrounds in any particular area may mitigate the risks and costs associated with immigration, facilitate job acquisition and increase earnings.

Another confounding issue is that of endogeneity. In addition to the possibility that immigrants come to SA with employment already confirmed (reverse causality), immigrants may be, on average, ‘more able, ambitious, aggressive, entrepreneurial, or otherwise more favourably selected than similar individuals who choose to remain in their place of origin’ (Chiswick, Citation1999:181). The strength and direction of this bias could be linked to the motives for immigration: positive selection is less likely among refugees, for example. If immigrants are, on average, positively (negatively) selected into the South African labour market then any immigrant disadvantage will be understated (overstated).

The MiWorc report does not mention or account for selection bias (Fauvelle-Aymar, Citation2014). Zuberi & Sibanda (Citation2004) recognise that unobservable endowments can contribute to immigrants’ success, but do not tackle the selectivity problem. Rather, they attribute their findings to the possibility that immigrants are drawn disproportionately from a pool of successful individuals in their home countries. Peters & Sundaram (Citation2015) partially address the selection problem by comparing immigrants only to SA’s internal migrants, arguing that because internal migrants may also be selected on positive labour market attributes they are preferred as a comparison group for immigrants. They provide no evidence in support of the assumption of positive selection, however.

Although it is problematic to assume ex ante that the direction of the selection effect is positive, we adopt the approach used by Peters and Sundaram and restrict our estimating sample to migrants only to address the endogeneity problem. We also instrument for immigrant status using information on an individual’s region of birth as well as macroeconomic information from the individual’s country of origin.

3. Data and descriptive statistics

In this paper we use the ten percent sample of the 2011 national Census data, collected by StatsSA, to study immigrants. The Census enables us to identify immigrants as individuals who were not born in SA, and to distinguish further between naturalised immigrants (SA citizens born outside SA) and foreigners (non-citizens born outside SA). This distinction is important: as we show in the descriptive analysis, naturalised immigrants and foreigners differ significantly in a number of observable ways, and naturalised immigrants have lived in SA far longer, on average, than foreigners. There may also be unobservable differences between these groups: the motives for emigration to SA could be different between immigrants who are naturalised and those who are not. Before 1990 most ‘authorised’ migrants to SA came from Europe and neighbouring countries (Crush, Citation2008). When naturalised immigrants originally entered SA, this may have been with the intention of seeking success under the protection of the apartheid government (for those entering prior to 1994) or under the auspices of new beginnings in the early years post-apartheid. More recently, foreigners (particularly those from Africa) may have entered SA in response to violence and unrest in their home countries. According to Crush (Citation2008), SA has become a prime destination for refugees from the rest of Africa since 1990. Differences in emigration motives can be thought of as relating to ‘pull’ and ‘push’ factors in SA and in immigrants’ home countries respectively, and could result in differences in selection into participation and employment for these groups. We therefore contrast naturalised immigrants and foreigners to individuals who were both born in and are citizens of SA, who we refer to as locals.

Labour market information is collected in the Census and identifying whether workers are wage or self-employed, and informally or formally employed, is possible. Industry and occupation information is also available. Since our focus is on labour market outcomes, we restrict the sample to individuals of working age (15–65 years).

One problem with using Census data is the limited breadth of information collected. The Census survey is short, capturing limited demographic and health information on individuals, their households, migration, employment status and total income. This limits our ability to identify an appropriate instrument to address the endogeneity problem using Census data alone, and requires that we explore additional options. Another pitfall of the Census data is that earnings information is not specifically collected. A crude measure of gross income is available, which may include income from grants, remittances, rental income, and interest, and it is impossible to isolate respondents’ earned income.Footnote1 Whether the collection of information on immigrant status is comprehensive is also of concern: individuals who are in SA illegally may avoid enumeration or provide false information, while those fearing xenophobic violence may falsely identify as locals. Our results may therefore underestimate the extent of immigration and the differences between locals and immigrants. However, any under- (or over-) counting of individuals should be mitigated by the Post Enumeration Survey, conducted directly after the Census. This survey is designed to determine the extent of any under – or over – count and is used by StatsSA to adjust the Census data. Throughout this paper we use probability weights to produce results at the level of the population.

The ten percent Census sample identifies approximately 30 000 naturalised immigrants and 97 000 foreigners of working age, representing populations of 361 000 and 1.19 million respectively (1.1 and 3.65 percent of SA’s working age population). shows that the vast majority of immigrants to SA were born in other SADC countries. More than seventy percent of naturalised immigrants and more than eighty percent of foreigners originate in SADC countries. Amongst naturalised immigrants, a further fourteen percent were born in the UK or Europe. In contrast, amongst foreigners, the second largest region of origin is the rest of Africa. Naturalised immigrants have been in SA for more than twenty years, on average, whilst foreigners have spent less than seven years in SA.

Table 1. Country of birth of working age immigrants to South Africa.

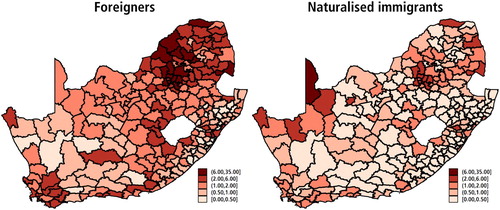

Foreigners and naturalised immigrants also differ in terms of their geographical location in SA. shows the percentage of working age residents in each municipality who fall into the two immigrant categories. The population density is higher for foreigners, who are the larger of the two immigrant groups, and foreigners tend to be closely clustered around SA’s north-eastern border (the point of entry for many SADC immigrants) and around the main economic hubs. In contrast, naturalised immigrants, who have typically been in SA for a longer period, are more geographically dispersed.Footnote2

Figure 1. Percentage of working age residents in each municipality who are immigrants. Source: Census 2011.

shows a number of significant differences in demographic and human capital characteristics between immigrants and locals that may impact on their labour market outcomes. Both immigrant groups are male-dominated: more than 58 percent of naturalised immigrants and almost two-thirds of foreigners are male. There are also many significant differences among immigrants. In terms of race, naturalised immigrants are much more likely than locals to be white, while foreigners are more likely to be African. Foreigners are significantly less likely than locals to have completed a matric-equivalent or tertiary level of education, whereas naturalised immigrants are almost four times as likely as locals to have attained tertiary education. Both immigrant groups live in smaller households than locals, with fewer children on average.

Table 2. Demographic and human capital characteristics, by immigrant status.

Labour market differences between naturalised immigrants, foreigners and locals are shown in . On average, immigrants are almost twenty percentage points more likely than locals to participate in the labour market (using the strict definition of participation). Amongst participants, immigrants are also more likely than locals to be employed, with naturalised immigrants having the highest employment probability (exceeding 86 percent). However, amongst the employed, immigrants are more likely than locals to be in self-employment, either on its own or in combination with wage employment. Foreigners are almost 20 percentage points less likely than locals to work in the formal sector. Naturalised immigrants who are employed have the highest total incomes of more than R17 000 per month.Footnote3 Locals earn half of that, while employed foreigners have the lowest incomes – less than R6 000 per month. These descriptive statistics thus suggest that on average, immigrants are more successful than locals in engaging with the labour market, but that some of them – particularly foreigners – may access more precarious forms of employment associated with low returns.

Table 3. Labour market characteristics, by immigrant status.

4. Econometric specification and results

We estimate the extent to which immigrants retain their average labour market advantage over locals controlling for other observable demographic and human capital characteristics.

The general model specification is as follows:(1)

(1) Depending on the model being estimated,

is either a binary labour market outcome (participation or employment) or the natural logarithm of income (in the earnings regressions). Immigrant status is included as two dummy variables,

and

, equal to 1 if the individual is a naturalised immigrant or a foreigner respectively, and 0 otherwise.

(where k = 1 for locals, k = 2 for naturalised immigrants and k = 3 for foreigners) is the social network proxy, defined in more detail below.

is a vector of control variablesFootnote4 (including controls for race, and years since immigration and its square), and

is the random error term. The parameters

and

indicate the extent to which the two categories of immigrants are advantaged (or disadvantaged) relative to locals.

As mentioned earlier, the Census does not explicitly collect information on social networks. We therefore create proxy variables, , to account for the influence of the social networks that individuals in the three immigrant status groups may access in SA. We hypothesise that individuals (particularly immigrants) may have better labour market outcomes if they access social networks that share information about employment opportunities.

We adapt a network measure proposed by Bertrand et al (Citation2000) to the immigration context, thereby incorporating aspects of both network quantity and network quality into our analysis. The extent of each individual’s network is calculated as the proportion of working age individuals residing in the individual’s municipality who share either the same province of birth (for locals) or country of birth (for immigrants).Footnote5 We augment the network size using a measure of network quality that reflects the networks’ potential to share information about the job market and employment opportunities. This network quality aspect is measured by the employment rate of the individual’s group (locals in each province, naturalised immigrants who share the same birth country and foreigners who share the same birth country) relative to the overall employment rate in the country. Social network access for an individual from region of birth R, living in municipality M, is therefore proxied by:(2)

(2) where

is the number of individuals born in region R living in municipality M,

is the population of municipality M,

is the employment rate of individuals born in region R, and

is the mean national employment rate.Footnote6

If there are more individuals of the same nationality living nearby, and if the employment share of the individual’s group in total employment is high, not only will an immigrant will find it easier to establish social networks,Footnote7 but the network is potentially able to provide better information about job market access, employment opportunities and high-quality jobs. The parameters in Equationequation (1)

(1)

(1) therefore indicate the extent to which the social networks available to locals, naturalised immigrants and foreigners augment or offset their labour market status.

However, although immigrants may choose their location because of the social network advantages that an area offers, a large component of immigrants’ locational choice may be influenced by the availability (or dearth) of economic opportunities. Not accounting for such differences in economic opportunities across locations may overstate the perceived benefits of access to social networks. Our analysis therefore controls for municipal-level economic status using municipal fixed-effects, in selected estimations.

We estimate probit models for participation and employment, and we use interval regression to obtain earnings estimates. Each group of explanatory variables is included sequentially in our estimations to observe how the labour market advantage (disadvantage) of immigrants changes as we control for their observable characteristics.

provides estimates of the average marginal effects from the probit estimations of labour force participation. Specification 1 reveals that both immigrant groups have a significantly higher probability of participating in the South African labour market than locals on average. As shown in specification 2, this advantage declines, particularly for naturalised immigrants, but remains significant when controlling for observable characteristics, including years since immigration and its squareFootnote8, but not the composition of the immigrant's municipality. More than half of naturalised immigrants’ participation advantage, and approximately 45 percent of foreigners’ advantage, is explained by their characteristics being more conducive to participation than locals’ characteristics.

Table 4. Probit estimates of labour market participation (marginal effects).

Specification 3 includes the social network controls, which reduce, but do not eliminate, the positive marginal effects for both naturalised immigrants and foreigners who lack network access. The social network effects are positive, suggesting that for all groups, and especially for foreigners where the coefficient is largest, access to social networks increases the probability of labour market participation. Controlling for municipal fixed effects in the final specification has a negligible effect on the significant participation advantage of both immigrant groups, but mitigates the effects of social networks. For locals the social network coefficient, while significant, becomes negative and very small (0.2 percent). Therefore, network size and quality may assist with participation at the aggregated geographical level for locals, but not within municipalities where competition may be greater. For both immigrant groups the social network coefficients decrease but remain positive and significant. Across all specifications, the pattern of performance is similar for naturalised immigrants and foreigners.Footnote9

repeats the probit estimation using employment status as the outcome variable. Compared to participation, there are some differences in the pattern of results for employment across specifications between naturalised immigrants and foreigners. Naturalised immigrants are initially at a 17 percent higher employment rate than locals, and have an almost 50 percent greater advantage than foreigners relative to locals. Controlling for the individual’s observable characteristics, the extent of access to social networks and municipal fixed effects reduces naturalised immigrants’ advantage to about 11 percent. The inclusion of controls for observable characteristics and years since immigration in specification 2 increases the foreign employment advantage relative to locals. On average, foreigners have been in SA for a shorter period than naturalised immigrants, and so accounting for years since immigration alongside the other control variables raises the probability of employment for foreigners. With all the observable factors included, foreigners’ employment advantage is around 13 percent. Social network access raises the probability of employment, particularly for naturalised immigrants who benefit the most from access to social networks but, like for participation, including municipal specific controls mitigates the effects of network access for all groups.

Table 5. Probit estimates of employment amongst labour market participants (marginal effects).

We next examine outcomes amongst the employed by analysing the returns to work. shows the results of the interval regression estimation of the natural logarithm of monthly income among the employed, conditional on an individual participating in the labour market and then obtaining employment.

Table 6. Interval regression of the log of monthly income of the employed.

The first column of shows that, unlike for participation and employment, only naturalised immigrants have a raw advantage over natives in terms of their income. In contrast, foreigners, on average, are at a large and significant income disadvantage, even without controlling for other characteristics. With controls for individual and household characteristics and years since immigration in specification 2, the income advantage of naturalised immigrants over locals is eliminated. In particular, the effect for naturalised immigrants becomes negative while the disadvantage for foreigners declines. This suggests that, relative to locals, naturalised immigrants have characteristics that are more productive in generating income, while foreigners have characteristics that are slightly less productive, but not sufficiently so to explain their entire income disadvantage. Specification 3 includes the social network proxies, which increase the magnitude of the income disadvantage for both naturalised immigrants and foreigners if they lack network access. Collectively, social networks appear to raise income, more so for immigrants than for locals. Specification 4 includes controls for job characteristics (the individual’s occupation, industry, sector (formal or informal) and employment type (wage-employment or self-employment)). There is no remaining income penalty for either immigrant group in this specification, suggesting that within a given job type, immigrants and locals with the same observable characteristics are paid equally. Controlling for occupational characteristics, the effect of social network access is reduced by more than two thirds for both naturalised immigrants and foreigners, such that it remains significant only for the latter, confirming that part of the role of social networks is to provide immigrants with access to better-quality jobs. When municipal fixed effects are included in specification 5, the results change minimally and the immigrant income differentials relative to locals remain insignificant. This suggests that any income effect of working in economically advantageous locations is accounted for through the measures of network access and job types. Therefore, although the raw income differentials between locals and immigrants differ in both direction and magnitude, neither immigrant group faces a penalty once all controls are included.

5. Addressing selection bias

The final part of the analysis explores whether our findings are robust to controlling for the possible endogeneity of immigrant status. If immigrants are motivated differently to locals in unobservable ways, then differences in labour market outcomes by immigrant status may be biased: that is, the advantage (disadvantage) faced by immigrants may be underestimated (overestimated). Furthermore, unobservable differences between naturalised immigrants and foreigners could result in different selection outcomes between these groups.

Our approach in this regard is twofold. First, following Peters and Sundaram (Citation2015), we re-estimate our full specifications for participation, employment and income using a reduced sample comprising immigrants and domestic internal migrants. Second, because our choice of individual-level instruments is limited by the paucity of information collected in the Census, we instrument for immigrant status and other immigrant-specific variablesFootnote10 using a combination of individual level and macroeconomic information.Footnote11 We use information on the individual’s region of birth – this is highly correlated with immigrant status, but we argue that after controlling for social networks and observable characteristics, it has no independent effect on labour market outcomes. We also use macroeconomic indicators of selected push and pull factors driving immigration decisions, namely information on the distance between SA and the immigrant’s birth country (and this variable’s square), GDP per capita in the immigrant’s birth country, and political stability in the immigrant’s birth country (measured by the POLITY 2 index).Footnote12

The results, adjusted for selectivity, are presented in (for participation and employment) and in (for income). In , since the potentially endogenous immigrant status is a binary variable, an instrumental variable probit model is unsuitable, and we estimate a linear probability model instead. We also re-estimate the participation and employment equations using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) for comparison purposes.

Table 7. The role of selection into immigrant status for participation and employment

Table 8. The role of selection into immigrant status for log of monthly income of the employed

The migrant sub-sample includes all locals who report having changed their place of residence within the past ten years, and all immigrants. Comparing the migrants-only OLS results in column 2 of to the full sample results in column 1 shows that the participation advantage declines by more than two-thirds, although still present, for both immigrant groups when they are compared to domestic migrants. Relative to all locals, the migrant sub-sample may therefore be a positively selected group with a smaller participation gap to immigrants. The magnitude and direction of the effects for the other covariates are also consistent across the full and sub-samples.Footnote13 However, a comparison of columns 1 and 3 shows that the significant immigrant participation advantage for naturalised immigrants is eliminated after using IV to control for the endogeneity of immigrant status, while for foreigners the immigrant participation advantage increases substantially. In particular, for naturalised immigrants, our IV estimate of the probability of participating is negative and substantial, while for foreigners the IV estimate is positive. This decrease in the size of the effect for naturalised immigrants, and the increase in the effect for foreigners is indicative of positive selection for naturalised immigrants but negative selection for foreigners, and is consistent with our earlier argument that not all immigrants may be positively selected. Controlling for endogenous immigrant status using IV increases the benefits of social networks for naturalised immigrants but not for foreigners, for whom the social network effect becomes negative.

The corresponding comparison for employment reveals similar results to participation. The employment advantage for the reduced sample of migrants is significantly smaller than for the full sample. In the IV approach, the employment advantage is completely eliminated for naturalised immigrants, although the resulting disadvantage is partially offset by a significantly increased benefit of social networks. For foreigners, the employment advantage increases, with foreigners having a higher probability of employment in comparison to locals of more than forty percent for those without network access. The now-negative influence of social networks offsets this higher probability, and suggests that there may be a competition effect among foreigners when controlling for the endogeneity of immigrant status in this way. As with participation, the directions of the change in the effects for both naturalised immigrants and foreigners (namely, smaller coefficient values for naturalised immigrants and larger coefficient values for foreigners) are suggestive of differential selection effects for each group.

To check the validity of the instruments used in our IV models we conduct tests that confirm that the immigrant status variables are endogenous. We also reject the hypotheses of under-identification and of weak instruments. However, using the Hansen-J test of over-identifying restrictions, we cannot confirm the validity of our instruments for either of the labour market outcomes.Footnote14 Our selectivity-adjusted findings using the IV technique should therefore be viewed tentatively.

As a final step, we address the endogeneity of immigrant status in the income analysis. Here, in addition to the problem of selection effects for immigration, selection into employment is also a concern. If the unobservable factors that determine who finds employment, like ability and motivation, are correlated with immigrant status, then the immigrant status coefficients will be biased. To control for this issue, we would need to find a variable correlated with participation, but not employment, and an additional variable correlated with employment, but not earnings. Unfortunately, the limited information captured in the Census precludes such exclusion restrictions.

shows our estimates for income, where we address the endogeneity of immigration status, but not the issue of selection into employment. The results presented here should thus be interpreted as conditional on an individual participating in the labour market, and then obtaining employment. Comparing columns 1 and 2 shows that there is a significant immigrant income disadvantage amongst the reduced sample of migrants, which did not exist in the full sample. Like for participation and employment, this suggests that the migrant sub-sample may be a positively selected group relative to all locals, and they outperform immigrants. In the reduced sample, the network effect for foreigners is larger and more significant than in the full sample, but is insignificant for naturalised immigrants. Comparing columns 1 and 3, the IV estimates of income for both immigrant groups are substantially larger than when the endogeneity of immigrant status is not accounted for. The income advantage for foreigners is double that for naturalised immigrants. Among income-earning employed individuals, immigrants, and especially foreigners, appear to be negatively selected, and controlling for selection improves their position relative to locals. This somewhat contradicts the results for participation and access to employment, where naturalised immigrants were shown to be positively selected. The social network effect for both immigrant groups is now large and significant, with a positive effect for naturalised immigrants and negative for foreigners, which is similar to the findings for employment.

Our attempts to tackle the potential endogeneity issue reveals two findings. First, restricting the native sample to domestic migrants results in estimates of the immigrant premium (or penalty) that are smaller than when selection into immigrant status is ignored. This is consistent with domestic migrants being a positively selected sample of all locals. Second, instrumenting for immigrant status reduces the advantage in participation and employment for naturalised immigrants, but increases it for foreigners and may reflect differences in the underlying motives for immigration between the two groups. This is consistent with positive selection for naturalised immigrants, but negative selection effects for foreigners. For naturalised immigrants, who have lived in SA much longer, on average, than foreigners and may have been ‘pulled’ to SA, there is evidence of positive selection. Their advantage in accessing the labour market thus becomes a disadvantage after controlling for endogeneity. For foreigners who have arrived in SA more recently, possibly being ‘pushed’ to relocate from their countries of origin, there is evidence of negative selection, and controlling for this increases their labour market access. In addition, the reduced effect of social networks for foreigners is consistent with these newer entrants into SA struggling, or competing with each other, to access the established social and communication networks necessary to facilitate access to employment. When considering incomes, our IV results are suggestive of negative selection for both immigrant groups: to some extent this may be reflective of constrained opportunities for advancement once in employment.

6. Concluding comments

We use population-weighted data from the ten percent sample of the 2011 Census to compare the labour market outcomes for working age immigrants and locals to determine whether the common perception that immigrants fare better in terms of participation, employment and earnings is warranted.

We initially find that, on average, immigrants are more likely than locals to participate and be employed. Using proxies to control for both the size and the quality of social networks, we show that part of this advantage is attributable to the networks that are accessible to some immigrants. Among immigrants, those with poorer access to social networks also have less access to the labour market and to employment. When controlling for worker characteristics, both naturalised immigrants and foreigners who are employed earn less income than locals, but social networks help them to access better quality jobs with higher incomes. Within specific job types, immigrants and locals with the same observable characteristics are paid equally, and networks provide no further benefit. Unlike in previous studies of labour market outcomes for immigrants in SA, our analysis therefore highlights and reinforces the importance of social network access to the ability of immigrants to succeed.

We attempt to control for the endogeneity of immigration status, firstly by repeating our analysis for a subsample of immigrants and domestic migrants and secondly using instrumental variable estimation. When compared to domestic migrants, immigrants’ advantage in labour market participation and employment is reduced. In comparison to domestic migrants, immigrants are also disadvantaged in terms of income. Comparing immigrants to all locals thus overstates their labour market performance relative to locals who have been motivated to migrant internally. The IV estimates suggest that the direction of the selection bias into immigrant status may be negative for foreigners, but positive for naturalised immigrants to SA. While this is consistent with foreigners being pushed and naturalised immigrants being pulled into the South African labour market, the implication is that the labour market access advantages for the two immigrant groups that we report may be overstated and understated respectively. However, it is difficult to determine to what degree any overestimation or underestimation of outcomes occurs, given the challenges of identifying an appropriate set of instruments.

If we focus on how immigrants perform once in SA our study suggests that immigrants may not necessarily outperform locals in the labour market as much as commonly thought, and that the generalised perceptions around immigrants’ economic and labour market success that feed xenophobic violence in SA may be exaggerated. Finding productive work in SA is challenging for individuals not born in SA, and immigrants largely make their own employment, and may generate lower incomes from this work than do locals. Further research is required to understand the environment in which immigrants live and work, the opportunities and difficulties they face, and how the social networks into which immigrants assimilate serve to facilitate labour market participation and employment and raise incomes. Broadening our understanding of the role and nature of social networks, among immigrants specifically and within SA more broadly, is linked to national government’s wider strategy to foster and accumulate social cohesion, dimensions of which include ‘building networks of relationships’ (OECD, Citation2011). To this end, a national strategy aimed at building a cohesive and inclusive society is already in place (DAC, Citation2012).

Finally, it is also important to recognise that there may be considerable variation in the distribution of labour market outcomes for immigrants around the mean. Further investigation of why some immigrants perform worse than others, and some better, is necessary to deepen our understanding of the complexities and challenges of SA’s labour market.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 All respondents are asked “What is the income category that best describes the gross monthly or annual income of (name) before deductions and including all sources of income?” Twelve possible response categories are provided, ranging from no income to R204 801 or more per month.

2 The main exception is the sparsely populated Mier local municipality in the far Northern Cape, which borders on Namibia and has a higher proportion of naturalised immigrants than foreigners.

3 In 2001 prices.

4 We control for gender throughout our analysis but do not present our findings separately by gender. The pattern of the results across labour market outcomes and model specifications is identical for both men and women, although the magnitudes of the coefficients differ somewhat by gender. In general, social networks play a slightly larger role for women than for men.

5 We thank an anonymous reviewer for the suggestion to refine the network quantity measure for locals using information on province of birth. We use data on approximately 233 municipalities and 176 reported birth countries.

6 Following Bertrand et al (2000), we do not calculate at the municipal level. Doing so may introduce omitted variable bias if the individual has unobserved characteristics in common with others from the same birth region living in the same municipality.

7 On average, among naturalised immigrants, 1.7 percent of other working age residents in their municipality were born in their same birth country, while for foreigners this figure is 2.7 percent. An immigrant’s network size is significantly negatively correlated with the length of time since they immigrated to SA, suggesting that new immigrants in particular locate themselves in close proximity to others from their birth country.

8 Note that this variable takes on a value of zero for locals.

9 in the Appendix includes the results for the full set of control variables for the models in . The full results for other models may be requested from the authors.

10 Specifically, we instrument for the two categories of immigrant status, social network access for the two immigrant groups, and number of years in South Africa and its square.

11 We extend our thanks to an anonymous reviewer for the suggestion to instrument for immigrant status using macroeconomic indicators.

12 For each of the GDP per capita and POLITY2 measures we use an average calculated over the 3 years prior to immigration for immigrants. For locals, we use GDP per capita and the POLITY2 index in the year the individual turned 16 years old. Our distance measure is coded as zero for locals.

13 Probit estimates for participation and employment for the migrant sub-sample similarly show smaller penalties to immigrant status and smaller network effects, compared to the full sample. These results may be requested from the authors.

14 The Hansen-J test results suggest that the validity of the instruments is similarly doubtful whether we use macro-level instruments only, individual-level instruments only, or instruments at both the macroeconomic and individual levels. However, the results of the IV estimation are more stable when we use the combined set of instruments, and this is therefore our preferred set of estimates.

References

- Adepoju, A, 2003. Continuity and changing configurations of migration to and from the Republic of South Africa. International Migration, 41(1), 3–28. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00228

- Adjai, C & Lazaridis, G, 2013. Migration, xenophobia and new racism in post-apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 1(1), 192–205. doi: 10.11114/ijsss.v1i1.102

- Bertrand, M, Luttmer, E & Mullainathan, S, 2000. Network effects and welfare cultures. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 351–77.

- Borjas, GJ, 1994. The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(4), 1667–717.

- Borjas, GJ, 1999. The economic analysis of immigration. Chapter 28, Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 1697–760. doi: 10.1016/S1573-4463(99)03009-6

- Chiswick, BR, 1993. Review of immigration and the work force: Economic consequences for the United States and source areas. Journal of Economic Literature, 31, 910–1.

- Chiswick, BR, 1999. Are immigrants favorably self-selected? The American Economic Review, 89(2), 181–5. doi: 10.1257/aer.89.2.181

- Chiswick, BR & Miller, PW, 2003. The complementarity of language and other human capital: Immigrant earnings in Canada. Economics of Education Review, 22(5), 469–80. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7757(03)00037-2

- Crush, J, 2008. South Africa: Policy in the face of xenophobia. Profile. Migration Policy Institute, Washington.

- Crush, J & Pendleton, W, 2004. Regionalizing xenophobia? Citizen attitudes to immigration and refugee policy in Southern Africa. Southern African Migration Programme, Canada

- Department of Arts and Culture, 2012. Creating a caring and proud society a national strategy for developing an inclusive and a cohesive South African society. DAC, Pretoria.

- Dustmann, C & Fabbri, F, 2003. Language proficiency and labor market performance of immigrants in the UK. The Economic Journal, 133, 695–717. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.t01-1-00151

- Dustmann, C & Glitz, A, 2005. Immigration, jobs and wages: theory, evidence and opinion, CEPRCReAM publication, London.

- Dustmann, C & Van Soest, A, 2002. Language and the earnings of immigrants. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55(3), 473–92. doi: 10.1177/001979390205500305

- Fauvelle-Aymar, C, 2014. Migration and employment in South Africa: An econometric analysis of domestic and international migrants (QLFS (Q3) 2012). Migrating for Work Research Consortium Research report 6.

- Karimi, F, 2015. What’s behind xenophobic attacks in South Africa? http://edition.cnn.com/2015/04/18/africa/south-africa-xenophobia-explainer/index.html.

- Kotze, H & Hill, L, 1997. Emergent migration policy in a Democratic South Africa. International Migration, 35(1), 5–36. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00002

- McDonald, DA, Mashike, L & Golden, C, 2000. Guess who’s coming to dinner? Migration from Lesotho, Mozambique and Zimbabwe to South Africa. International Migration Review, 34(3), 813–41. doi: 10.1177/019791830003400307

- Montgomery, J, 1991. Social networks and labor-market outcomes: Toward and economic analysis. American Economic Review, LXXXI, 1408–18.

- Munshi, K, 2003. Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the US labor market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2(1), 549–99. doi: 10.1162/003355303321675455

- Neumann, KE & Massey, DS, 1994. Undocumented migration and the quantity and quality of social capital. The Population Research Centre, University of Chicago and NORC, Chicago.

- OECD, 2011. International conference on social cohesion and development: Background. http://www.oecd.org/dev/pgd/internationalconferenceonsocialcohesionanddevelopment.htm

- Peters, AC & Sundaram, A, 2015. Country of origin and employment prospects among immigrants: An analysis of south–south and north–south migrants to South Africa. Applied Economics Letters, 22(17), 1415–8.

- Posel, D, Casale, D & Vermaak, C, 2014. Job search and the measurement of unemployment in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 82(1), 66–80. doi: 10.1111/saje.12035

- Sinclair, MR, 1999. I Know a place that is softer than this … emerging migrant communities in South Africa. International Migration, 37(2), 465–81. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00080

- StatsSA, 2016. South African Census, 2011, 10% sample [dataset] (Version 1.2). Pretoria: Statistics South Africa (Producer) and Cape Town: DataFirst (Distributor). http://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/485.

- StatsSA, 2018. Youth unemployment still high in Q1: 2018. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=11129; accessed 13/08/2018.

- Zuberi, T & Sibanda, A, 2004. How do migrants fare in a post-apartheid South African labor market? International Migration Review, 38(4), 1462–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00244.x