?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

While it is well documented that severe consumer indebtedness can lead to mental and physical health problems including unhealthy coping mechanisms, the pathways from poor health to financial strain is still an understudied area. Using the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) data, this study examines the relationship between poor health and debt distress while controlling for the possible endogeneity between these two conditions and some health-related variables. The results indicate that poor health significantly increases the probability of financial strain. Insofar as poor health is associated with catastrophic healthcare costs and income deprivation, for instance through inability to work, other factors affecting health such as socioeconomic status and insurance might shape the contours of consumers’ debt performances in the face of health risk. Ultimately, health may be creating a vicious circle in which poor health affects the capacity to earn income and accumulate assets, which limits access to quality healthcare.

1. Introduction

As the consumer credit industry continues its rapid expansion in South Africa, it is likely that household shocks will continue to exacerbate debt problems unless the credit regulatory framework evolves accordingly (Ssebagala, Citation2016a). Health shocks continue to be one of the most important risks of the household sector, affecting incomes, productivity and general wellbeing. Despite the free public healthcare system, huge inequalities in access to quality healthcare still exist to the effect that a considerable portion of the population is forced to rely on cripplingly costly private healthcare arrangements (e.g. Harris et al., Citation2011) while, for others, a lack of access to the basic requirements of life greatly affects health (Mayosi & Benatar, Citation2014). Health shocks and the cost of accessing healthcare impose huge burdens on families’ overall welfare whilst, engendering financial distress ‒ especially among the poor and rural populace for whom health insurance coverage and private savings are often inadequate or non-existent (see Collins & Leibbrandt, Citation2007; Knight et al., Citation2015).

A negative health shock is associated with not only the financial cost of treatment (Jacoby & Holman, Citation2013), but also income deprivation through inability to work or accumulate wealth and will insidiously undermine individual productivity (see Liu, Citation2014; Blázquez & Budría, Citation2015). Given such outcomes, the unfortunate households will more often than not resort to costly smoothing stratagems which often engender further negative knock-on effects on their socioeconomic wellbeing (see Liu, Citation2014), especially by bloating their financial obligations. This relationship is further complemented by other factors that affect health, including socioeconomic status, lifestyle or life-cycle effects such as age. The notion espoused here is that the chances of falling into health-related debt and/or the inability to manage other financial obligations increase disproportionately for people with poor socioeconomic status, unhealthy lifestyles and as they age (e.g. Braveman et al., Citation2005). This is because such factors not only increase the health risk of individuals and/or reduce the capacity to respond to negative health shocks, but also impair earning potential.

Obtaining definitive evidence for these relationships is quite challenging mainly because the direction of causality can theoretically go both ways. Debt stress might itself have adverse health outcomes, most notably stress and psychological disorders (e.g. Bridges & Disney, Citation2010), and might also expose people to other unhealthy coping behaviours such as smoking, alcohol or drug abuse (e.g. Meltzer et al., Citation2013; Blázquez & Budría, Citation2015). Furthermore, consumption patterns might be influenced by consumers’ hidden characteristics (e.g. attitudes towards borrowing) or by exogenous factors (e.g. credit rationing criteria).

Consumer over-indebtedness is a socioeconomic problem insofar as it interferes with consumption potential and exposes consumers to other economic hardships (Micklitz & Domurath, Citation2015; Krumer-Nevo et al., Citation2017; Ssebagala, Citation2017). As such, understanding the dynamics through which health and health-related factors interact with consumer debt performance is a compelling social policy issue, especially in South Africa where consumer indebtedness is still an understudied area. This is the principal objective of this paper.

Despite the wide-ranging concerns consumer over-indebtedness generates among policy makers and scholars alike, the lack of a uniform definition of this phenomenon across countries and studies (Keese, Citation2009; Brix & McKee, Citation2010) is quite surprising. A few studies have relied on the statistical (objective) indicators that quantify and use the gross stock of debt, and/or debt-to-income ratios to evaluate households’ debt sustainability (e.g. Lyons & Yilmazer, Citation2005; Brown & Taylor, Citation2008; D’Alessio & Lezzi, Citation2013; Ssebagala, Citation2016b). Other studies have relied on, individuals’ self-assessed difficulties (Betti et al., Citation2007; Krumer-Nevo et al., Citation2017) or levels of sacrifice endured in paying obligations (e.g. Del-Río & Young, Citation2005; Guérin et al., Citation2013).

Although D’Alessio & Lezzi (Citation2013) have argued that debt can increase relative to income without necessarily making debt management problems more acute (especially among higher-income households), an earlier British study by Del-Río & Young (Citation2005) found that in general there is a clear link between the subjective measure of financial distress and the relative indicators of debt affordability. In this regard, the size of the unsecured debt-to-income ratio will shape the contours of households’ financial performances with some households reporting their debt to be either somewhat of a burden or a heavy burden for others.

Regarding the association between financial problems and health, many scholars see the direction of causality running from financial hardship to adverse health outcomes. For instance, being unable to pay bills appears to be related to mental health and depression or even suicidal tendencies (Meltzer et al., Citation2011), while simply being in debt increases the likelihood of sub-health conditions and behaviours such as alcohol and drug abuse (Meltzer et al., Citation2013).

Only a handful of studies have explored the direction of causality running from poor health to severe indebtedness, and these mainly point to the increasing unaffordability of medical care and inequities in health insurance coverage (e.g. Doty et al., Citation2008; Himmelstein et al., Citation2009; Ramsay, Citation2009; Emami, Citation2010). For instance, studies in the United States have found a direct link between accumulation of medical bills and consumer bankruptcies (Himmelstein et al., Citation2009), debt repayment difficulties (Doty et al., Citation2008), or overall increases in consumer financial burdens (Lyons & Yilmazer, Citation2005) even among those with medical insurance, which Doty et al. (Citation2008) attributed to the huge gaps in coverage and the high rates of cost-sharing.

For households in the United Kingdom, a study by Ramsay (Citation2009) found that general ill-health and/or disability accounted for 5% of households reporting financial difficulties. Similarly, a 2006 German study by Angela (Citation2008), found sickness, accidents and addiction to rank fourth among the personal reasons for being over-indebted, while Backert et al. (Citation2009) reported that psychological problems and other ailments jointly ranked fourth among the reasons German consumers found themselves over-indebted and/or filed private bankruptcies.

In the case of South Africa, to the best of my knowledge, no contribution in the literature on the direct relationship between ill-health and debt distress has been uncovered thus far. There are, however, two empirical studies that highlight some pathways between health-related shock and household financial fragility. A study by Knight et al. (Citation2015) in peri-urban and rural KwaZulu-Natal found health to be the second most reported household shock (30%) including death, injury or serious illness of a household member. Most importantly people confronted with such shocks are less likely to apply asset-based coping strategies (e.g. use of savings and investments or liquidation of assets) because they tend to have few assets of value, a limited market for selling them and negligible savings to draw on (Citation2015:225). Another study by Collins & Leibbrandt (Citation2007), using the South Africa ‘Financial Diaries’ dataset, notes that a major pathway through which HIV/AIDS impacts on household wellbeing is through the socioeconomic impacts of death, and the subsequent funerals, which often cost up to seven months of income. More so, 61% of households were found to be underinsured against such costs. More poignant yet is the observation that death poses such substantial and lingering burdens that financial provisioning for medical treatment and care seem to take second place to coping with the costs of death (Citation2007:76–81). Another descriptive study by Hurwitz & Luiz (Citation2007) found that debt-distressed households (i.e. those spending 30% or more of their gross monthly income on debt) were more likely to have a lower socioeconomic status, and to have experienced a negative shock (e.g. a recent retrenchment or a recent death in the family).

These studies illustrate an unmistakably strong correlation between health-related shock and consumer financial fragility. For studies interrogating the pathway from ill-health to debt distress, the common denominators appear to be the financial burdens associated with responding to an adverse health condition such as out-of-pocket medical expenses (Emami, Citation2010), and the costly smoothing mechanisms that consumers employ during or following the health shock (e.g. borrowing more, or discontinuing payments) which, according to Liu (Citation2014) can be mitigated by equitable access to health insurance.

This paper contributes to this extant literature by empirically analysing this relationship in the South African context and provides a basis for further empirical investigation. The study employs data from the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) to investigate whether, and to what extent, severe consumer indebtedness is driven by poor health outcomes. The study posits that given the possible costs associated with illness and/or inability to work through illness or injury, experiences of ill-health are likely to trigger severe consumer indebtedness ‒ controlling for an individual’s health-related conditions (i.e. negative changes in income, socioeconomic status, body weight and age). Thus, health-friendly conditions are likely to reduce the propensity for debt distress and vice versa. It is further assumed that consumers faced with negative health shocks will attempt to smooth their consumption through a number of ways including multiple borrowing (see Meier & Sprenger, Citation2010) or suspending scheduled payments on their outstanding financial obligations. Unfortunately, such arrangements often only serve to exacerbate their financial fragilities and ultimately the interaction between health and debt becomes a major social policy concern. Throughout the paper the terms ‘debt distress’ and ‘over-indebtedness’ are mutually interchangeable.

2. Data and methodology

This study uses data from waves one (2008), two (2010) and three (2012) of the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) to investigate the relative importance of poor health in consumer debt distress. Conducted by the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) at the University of Cape Town, the NIDS is a biennial panel study of individuals’ income mobility (or lack thereof).

The NIDS employed a stratified, two-stage cluster sample design in sampling households for the base wave with a panel comprising of 28 226 individuals in 7305 households. Initially, 400 Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) were selected from Statistics South Africa’s 2003 Master Sample of 3000 PSUs (Leibbrandt et al., Citation2009:9). The sample comprised private households in all nine provinces of South Africa excluding some collective living quarters such as student hostels, old age homes, hospitals, prisons and military barracks. A detailed description of the NIDS sampling design can be found in Leibbrandt et al. (Citation2009).

The NIDS, collected household-level information using a household questionnaire, while individual-level information was collected using a separate questionnaire administered to all individuals in these households who were 15 years and older during wave one. The total number of individuals successfully interviewed in wave one, two and three were 25 371; 21 617; and 22 375 respectively. To avoid possible biases in the interpretation of results that might result from non-random attrition, the current study selected only individuals successfully interviewed in all the three waves (n = 18 864).

The unit of analysis in this study is the individual as opposed to the household following the basic assumption that, given the realities of intra-household inequality, even in a single household, members cannot be expected to pool resources and/or share financial responsibilities equally. Intra-household resource allocation literature affirms that there exists intra-household inequalities experienced across material and non-material dimensions with respect to (among others) investments in education and health, nutrition, ownership of assets, wealth levels and consumption, which if ignored may greatly distort the general level of poverty and inequality (Lise & Seitz, Citation2011; Malghan & Swaminathan, Citation2016). This is especially compelling in a context like South Africa, where individuals often belong to more than one household, and move between households to access resources and care, or even to evade responsibility (see Seekings & Nattrass, Citation2008).

Having noted the lack of a uniform definition and benchmark for consumer over-indebtedness across countries, the current study adopts an objective (relative) measure of over-indebtedness wherein a consumer is over-indebted if he/she spent 25% or more of his/her gross monthly income on consumer (unsecured) debt servicing. This choice is guided by available literature, inter alia, D’Alessio & Lezzi (Citation2013) on the definition and measurement of over-indebtedness in Italy as well as Elaine Kempson (Citation2002) and DTI-MORI (Citation2005) for the British Department of Trade and Industry reports on over-indebtedness. These three studies also espoused a 50% threshold if secured obligations are included, but D’Alessio & Lezzi (Citation2013) noted that since the risks associated with secured debt are basically covered by collateral, it makes better sense to restrict the analysis to unsecured payments. In comparison, two South African studies, Collin’s (Citation2008) and Hurwitz & Luiz’s (Citation2007) adopted 20% and 30% thresholds respectively but both analyses were not restricted to a particular debt type. Note however that just like all other measures of over-indebtedness, the measure adopted here is not without its own caveats most notably the possibility of misevaluations. For instance under this measure, young people and other urban low-income working folks will have a high propensity to debt, given their relative low-income status and therefore it is possible to incorrectly consider them over-indebted, when they are not. According to Falanga (Citation2015) this problem could be solved using a different threshold for young people (and perhaps rural and urban dwellers), but determining that threshold is equally problematic.

By assumption, an individual’s debt distress is a function of the actual state of health and other factors that affect health. Suppose then that an individual’s health is a function of his/her ability to respond to or manage health shocks and to exploit health-friendly technologies and knowledge that are represented inter alia by, socioeconomic status (SES), physical condition and income stability.

Then,(1)

(1) where (X) is an indicator of previous or existing health conditions (i.e. ill-health) of the individual (i), measured as a binary variable (1/0): if an individual reported being diagnosed with any one of the illnesses cited on the questionnaire (i.e. TB, high blood pressure, diabetes, a stroke, or asthma, heart problems, cancer, other/disability) at any time (t) between 2009 and 2011. (HE) is a vector of health-related effects associated with socioeconomic status (SES) (i.e. income, medical insurance, employment, and education attainment including an interaction term for income and employment), individual condition (Co) represented by one’s position in the life-cycle and body weight (i.e. age and BMI respectively), and possible income shocks (Sk).

Following these assumptions, a binary logistic regression model is estimated of the general form:(2)

(2) where P is an indicator of whether an individual i was experiencing debt distress or not, at the time t, and (Ct) is the covariate for possible consumption smoothing effects which are explained in this context by multiple borrowing which some consumers might resort to in their bid to bridge consumption in times of financial strain (see Liu, Citation2014). In their smoothing attempts consumers may be forced to borrow small amounts from multiple sources if their financial strain renders them less creditworthy and therefore less able to borrow their desired amounts from a single source. α1, α2 are the parameters estimated with a constant (α0) and (

) is the idiosyncratic error.

Expanding the above equation yields:(3)

(3) Inasmuch as severe indebtedness can emerge simultaneously with an adverse health event, whilst available literature shows that indebtedness can be both a cause and a consequence of adverse health/SES, this kind of endogeneity is avoided by employing a dynamic specification wherein the predictors (X, SES, Co, Sk, and Ct) are measured in the year/wave (t−1 to t) prior to the year the debt distress was observed t + 1 (2012). Such a specification also underpins the assumption that the movement from poor health to financial strain will develop over time. For the sake of complementarity, a conditional fixed effects model was estimated to compare the results of the logistic regression analysis (see Appendix B).

To avoid possible multi-colinearity, especially given the assumptions behind the health function (Equationequation 1(1)

(1) ), a pairwise correlation test was conducted for all the variables of interest and only variables with a correlation not exceeding 0.50 were included (Appendix A). Some of the variables dropped due to multi-colinearity include asset value, marital status and homeownership and the choice on which variable to drop or retain among the highly correlated pairs was based on the strength of the relationship between the variable in question and health (HE in model 1). presents the detailed definitions of the variables of interest. Monetary values were adjusted for inflation and expressed in 2012 South African Rand.

Table 1. Detailed variable definition.

Given the sensitive nature of the subjects investigated in this study notably debt and poor health, a note on ethical considerations is in order. The duty of care was observed regarding, inter alia, sample selection, confidentiality and data integrity. No attempts to identify or contact individual respondents were made, and the research methodology employed presents no potential unintended consequences to the sampled population (e.g. disclosures of sensitive information, personal injury or prejudice). The methodology also fits well the aims of the study and has been widely used to answer similar questions. Additionally, although the NIDS was not designed specifically to investigate ill-health and indebtedness, it is the best available panel dataset for this purpose given its emphasis on personal economic mobility.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

The contrast in this study is between the ‘types’ of consumers for whom health risk is likely to be a source of financial distress in a sense that it threatens future earnings and/or strains available resources through healthcare bills. In this study, debt distress is defined as having a monthly consumer debt service ratio of 25% or more, but it should also be noted that without information on borrowers’ self-assessment of distress or actual delinquency, it is difficult to determine at what point one’s debt service ratio becomes a genuine problem. Still, it’s important to reiterate that the primary consideration here is not the absolute debt levels so much as the relative levels.

For the subsample successfully interviewed in all the three waves (n = 18 864), only 12 113 individuals responded to the question on consumer debt use which represents 64% of this subsample. For these, only 2139 individuals held consumer (non-housing) debt in 2012 which represents 18% of the subsample. For these individuals, the average consumer debt outstanding was R11 006, while the mean debt service ratio was 39%. The relatively larger standard deviations of R24 838 and 109% respectively () are intuitive and concur with Falanga (Citation2015) who observed that the standard deviation of almost all survey data about arrears is very high compared with the average. They also confirm the intrinsically asymmetrical nature of the overall distribution of consumer debt among consumers based (at least in part) on the resource inequalities among the population. By design, the credit market will impose borrowing limits on individual borrowers consistent with their ability to pay – such that, even in the same household, some members might report no debt at all, although other household members might be heavily indebted. Moreover, the low borrowing rates observed might be explained by the natural tendency of consumers to underreport arrears during surveys probably due to the sensitive nature of this information (see Citation2015:25). For the sample successfully interview in all three waves, 45% spent 25% or more of their gross income on debt servicing (and therefore were considered to be over-indebted based on the study’s criteria). presents the distribution of consumer debt outstanding among the different consumer subgroups and identifies which subgroups are likely to be debt-distressed based on the defined threshold.

Table 2. Distribution of consumer debt (n = 2139).

Table 3. Consumer debt performance against selected variables.

As hypothesised, debt distress can be a function of poor health, conditional on other personal attributes that affect health (e.g. medical insurance or lack thereof, stability of employment, and experiences of income shock, income, and age). It is clearly elucidated in that individuals diagnosed with a major illness are on average more likely to be among those with severe indebtedness. This situation is likely to be compounded by the concurrence of shocks to income.

As such, a significant positive relationship is observed for income shock. Conversely, access to medical insurance, having a relatively higher income or being in regular employment are factors that are likely to mitigate the situation and thus insulate consumers against severe indebtedness. In this case, if they should suffer illness or injury, such individual will be better positioned to access functional healthcare without necessarily jeopardising their debt performances. Additionally, such (health-friendly) situations reduce the overall risk of poor health. Hence, access to medical insurance, being in regular employment, and income had a statistically significant negative relationship with debt distress. Education attainment was also significantly negatively related to the debt-service burden, a relationship that can be explained either by the fact that education can proxy for higher future earnings or the assumption that education increases awareness of health dynamics. However, no statistically significant results are observed for age and body weight (BMI).

There is not much of a difference observed in the size of debt outstanding with regards to experiences of ill-health or income shock versus not experiencing either, which might be intuitive given that both conditions are likely to impinge on the individual’s creditworthiness. Conversely, robust statistical differences can be observed between the level of outstanding debt held and income, as well as other SES effects (i.e. medical insurance, work status, wealth). Most notably the amount of outstanding consumer debt is significantly higher for consumers whose characteristics suggest positive income and vice versa. The size of outstanding debt also increases with the number of debt commitments, while it appears that the debt load will increase with age peaking at the 41–50 age bracket, then falling as consumers presumably, move towards retirement.

Based on these bivariate relationships, one line of thinking holds to a larger extent: thus there is an inverse relationship between the absolute size of debt held and the debt service-burden. Where statistically significant (except in the case of age and number of debt commitments), the positive correlates of a high debt service ratio are negatively related to the debt outstanding and vice versa. This is hardly surprising given that the level of borrowing is a function of visible characteristics of consumers with which lenders can verify creditworthiness. To the extent that lenders evaluate risk, a higher likelihood of debt distress will increase the propensity for credit rationing and vice versa. Moreover it has been observed in international literature that even though the absolute amounts of borrowing by consumers in precarious socioeconomic situations is generally relatively small, such consumers are more likely to have the highest debt ratios and/or report debt as being a huge burden (e.g. Brown & Taylor, Citation2008; Kim et al., Citation2017). These bivariate correlations are, to a larger extent, intuitive and indeed show that a heavier debt service burden is positively correlated with poor health and other factors that compromise health. Positive and negative health-effects have a diametrical relationship with financial distress, which is dissimilar to how these effects influence health status itself.

3.2. Estimation results

By design, poor health interacts with debt performance through medical care costs or the inability to afford these costs, controlling for other factors that affect individual wellbeing such as income and wealth, employment, and education. presents the logistic regression estimation results of the interaction between debt performance and ill-health controlling for both the dual endogeneity between debt and health, and some determinants of health (coefficients, odd ratios, marginal effects and their robust standard errors). Thus, the probability of being over-indebted (having a consumer (unsecured) debt burden equal to or in excess of 25%). With regards to the relationship between debt distress and personal characteristics including shock, the results are broadly consistent with those observed in other South African studies (e.g. Hurwitz & Luiz, Citation2007; Collins, Citation2008; Ssebagala, Citation2016b).

Table 4. Logistic regression estimation results.

The multivariate logistic regression results suggest that debtors who were diagnosed with a serious illness (at any time between 2009 and 2011) were more likely to be found over-indebted (in 2012) ‒ controlling for other health-related factors (i.e. medical aid, income shock, employment, income, education, age and body weight) and the number of debt commitments held. Because these health-related variables are either likely to influence the consumer’s ability to manage his/her indebtedness in the face of a health risk, or directly influence their health status, their relationship with debt distress is conditional on their interaction with health. For instance, the relationship between ill-health and the debt-service burden is likely to change according to the different conditions of income or knowledge of debt management and health dynamics, which can result from education attainment. As such, conditional on health status, the probability of being over-indebted significantly increased with experiences of income shock. Contrariwise, through their interaction with health status, characteristics that are suggestive of positive SES (i.e. medical insurance, stable employment, education attainment and income) show a significantly negative relationship with debt distress and a divergent relationship is expected for consumers without these attributes. Additionally, controlling for health status revealed that the probability of over-indebtedness increased with the number of consumer debt commitments held, but no statistical significance is observed for personal conditions (i.e. age and body weight). The interaction term for income and employment was also statistically significant (but counterintuitively) positively related to debt distress.

Inasmuch as the interaction of health status and indebtedness is affected by other health-related factors, the explanatory power of ill-health on the probability of being debt-distressed is presumed to vary based on the combination and the values of the other explanatory variables in the logistic model. It then makes sense to illustrate their individual effects using conditional marginal effects. The results of which are also presented in and show that for an average individual (with mean values for the other predictors in model), the probability of having a debt service ratio equal to or in excess of 25% increases by 7 percentage points if the individual had been diagnosed with a serious medical condition versus one who had not suffered a medical condition. Also conditional on other individual characteristics, having medical insurance is likely to reduce the probability that an average consumer will experience debt distress by 17 percentage points compared to having no medical insurance. With regard to experiencing an income shock, the probability of debt distress increases by 30%, while education attainment is likely to reduce the probability of debt distress by 2.5 percentage points with each level of education attained conditional on other predictors.

Overall, the estimation results show that poor health is likely to have a negative effect on consumers’ capacity to manage their indebtedness which suggests that health-related expenditures and income loss are decidedly onerous. It appears, however, that this effect is either attenuated or amplified by other individual characteristics, either through a direct effect on income or indirectly through individuals’ capacity to maintain positive health, deal appropriately with health risks and reduce the propensity for costly smoothing mechanisms. Moreover, the negative conditional relationship between medical insurance and debt distress could be a major source of heterogeneity between debtors who experience poor health, especially with regard to health-related expenditures.

Because identifying causal effects of debt distress may requires exogenous variation in consumption behaviour (for instance lenders might target consumers with certain characteristics), a selection risk can be assumed. Mindful of this possible dual endogeneity problem, a different model was estimated with the same set of variables for comparability purposes (Appendix B). This conditional fixed effects model (with the time variable created from the 3 panels) was estimated to account for the unmeasured time-invariant confounders. The results were similar to those obtained from the logistic regression analysis with no change in the significance of the predictors or the signs on their coefficients. Therefore it is fair to conclude that those characteristics observed in the logistic (main) model are unique to the individual and are not correlated with other individual characteristics.

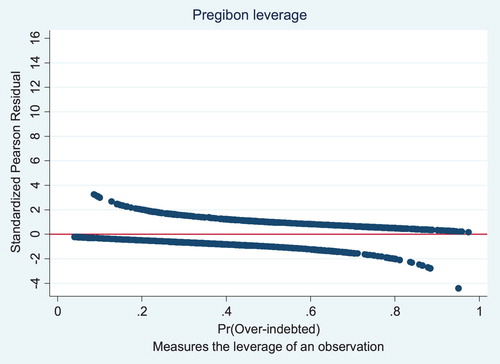

The post estimation diagnostics employed did not detect multi-collinearity even though some predictors might appear closely related (for instance BMI and ill-health). It also appears that no observations exerted undue leverage on other observations in the model after plotting the standardised Pearson residuals, deviance residuals and the Pregibon leverage against the predicted probabilities and index numbers (). Additionally, diagnostics such as Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (P = 0.46) and linktest (_hatsq = 0.491, _hat = 0.000) also suggest that the model did fit the data and was correctly specified.

4. Discussion

The main issue of contention is whether poor health can be an important cause of consumer debt distress or whether both are independent unfortunate conditions that afflict individuals. Available studies have mostly interrogated the effect of debt distress or debt on health and concluded that indeed severe indebtedness or arrears, have serious effects on health. The outcomes mostly cited include depression, stress, mental disorders and other negative health-inducing behaviours such as drinking and drug abuse. But a few of these studies have invariably hinted (often mundanely) at a possibility that the causality may also run in the opposite direction where severe indebtedness might result from poor health and/or poor health attributes. The findings in the current study lend credence to this supposition.

If suboptimal conditions of life (such as low SES, unhealthy conditions, sedentary lifestyles and negative shocks) can induce poor health and vice versa, and if poor health can undermine productivity, wealth accumulation and can escalation demands on available resources, then unhealthy consumers with inadequate resource are likely to find their debt performance deteriorating fast. They may be forced to borrow beyond their means, or renege on existing financial obligations. In the end, they may lack the wherewithal to adhere to health-seeking behaviours as smoothing consumption becomes the overriding concern, which might also become increasingly harder to manage as their credit ratings continue to deteriorate. The presence of medical insurance can have an important mitigating effect and may reduce the propensity for costly smoothing strategies.

Using an indicator of debt distress with a threshold defined as spending 25% or more of monthly income on monthly consumer debt payment in a dynamic specification that attempts to control for the assumption that debt distress can be both a cause and a consequence of poor health, the study found that consumers were significantly more likely to experience debt distress if they were diagnosed with an adverse health condition. It also appears that, for these consumers, the variance in the probability of debt distress can be affected by other factors such as experiences of income shock, income levels, medical insurance, education and employment. In the logistic regression model, experiences of income shock and the number of debt commitments held had a significantly positive relationship with debt distress, while medical insurance, employment, income and education attainment were significantly negatively related to debt distress. These relationships were consistent even in the fixed effects model.

Depending on one’s health status, it appears that these characteristics may be the difference between a consumer experiencing, avoiding or ameliorating financial distress. These factors also determine how severe one’s financial strain may turn out. For instance, negative health attributes like income shocks will reduce the ability to manage health shocks and will have a direct effect on ability to manage debt repayments. Inversely, positive health attributes like insurance, employment or education, will not only provide tools for responding to health needs, managing health shocks and reducing the consumers’ sensitivity to such shocks, but will also have a direct effect on the ability to maintain debt payment.

Take medical aid as an example. Consumers with medical insurance (almost always the preserve of employed and/or higher-income individuals) are for the most part insulated against huge out-of-pocket bills. Confronted with a health shock, they may not resort to unmanageable borrowing or default unlike their uninsured counterparts (often the low-income and sub-employed). Similarly, education attainment may affect health outcomes (and ultimately debt sustainability) both through its relationship with income and by making it easier to use and benefit from health information and health-friendly technologies. Furthermore, higher-income individuals will have less trouble paying medical bills or deductibles than those who fall into the low-income bracket.

It appears then that the odds are stacked against the poor. Besides the fact that they largely lack access to the basic requirements for life like, inter alia, healthy nutrition, appropriate child nurturing, or effective sanitation, they are also less likely to be insured both against income fluctuations and health risk, and have limited to no means to cater for huge health-related costs, yet are more exposed to health risks than their wealthier counterparts. Often, the poor may not be able to borrow their desired amounts due to poor credit ratings. They are risky customers because they will have trouble paying back even the little that they are able to borrow due to the myriad other risks arising from their low SES. Ultimately, low incomes and wealth affect consumers’ capacity to borrow just as poor health affects their capacity to earn income and gain wealth, thereby creating a vicious circle wherein their financial strain affects their ability to afford quality healthcare and inevitably leading to an overall deterioration in quality of life.

Admittedly, even with the lenders’ intrinsic profit motive and loss-aversion, there will always be spillages in the credit evaluation system, which allow debtors to qualify for more debt than they can reasonably afford. Nonetheless, controlling for possible confounders, negative shocks and their associated costs are likely to be more binding in consumers’ debt distress than borrowers’ or lenders’ behaviours. This is also supported in other available studies both in South Africa and elsewhere (e.g. Getter, Citation2003; Keese, Citation2009; Ssebagala, Citation2016b).

6. Conclusion and implications

This paper presents evidence on the role of poor health in personal debt distress among South African consumers. While the study is not meant to dispute the findings from previous research that find severe indebtedness or debt to have serious effects on health, it confirms the unexplored supposition of some of these studies and with strong evidence that indeed the direction of causality can also be primarily from health to financial distress. By controlling for health-related characteristics, which are represented by the three parameters of negative changes in income, socioeconomic status and personal condition, as well as the number of commitments, it appears that those most likely to be affected are the low-income consumers with little means to pay medical expenses or insure themselves against health risk.

The results in a nutshell, demonstrate that debtors who experience negative health or those exposed to poor socioeconomic conditions are most likely to wind up in financial distress, even though these are less likely to be heavily indebted in absolute terms. Given their precarious situations, they might desire to borrow more, but they are less likely to qualify for more. As such, they may be prevented from improving their socioeconomic positions, accessing quality healthcare or improving their overall quality of life. Such a vicious circle may not bode well for economic equality and financial independence.

It is also helpful to note that the South African government has made great efforts to introduce social policies aimed at reducing health inequality and poverty in the last 20 years. For instance the number of social grants to the very poorest and unemployed has greatly increased, increased funding for public healthcare and a new national scheme was initiated for training physician scientists through an M.B., Ch.B./Ph.D. programme in an attempt to sustain academic medicine (Mayosi & Benatar, Citation2014). Nonetheless, health inequalities endure, with much of the public healthcare infrastructure run down and dysfunctional due mismanagement especially in the rural areas.

These findings have implications for assessing the diffusion of social safety nets as it appears that there are pockets of vulnerability in the South African household sector with regard to indebtedness resulting from the gap in healthcare accessibility. Providing households with more affordable healthcare services and other social service options through which the poor can smooth out shocks may result in improved health outcomes, protection of personal incomes and ultimately afford the poor a modicum of serenity in the face of hardship. The whole spectrum of welfare arrangements should be improved, including a comprehensive and balanced healthcare coverage. Creating social insurance schemes with a special focus on the low-income, should be explored to assist those in unstable employment, and rural households.

Additionally, if households faced with expensive health conditions were able to draw on their savings, liquidate some assets, or withdraw home equity, they would be able to sustain their ongoing subsistence and debt positions. Unfortunately, the majority of South Africans are not in that position and that is something consumer protection and education efforts need to take into perspective. Furthermore, insofar as severe indebtedness can be a consequence of consumers being surprised by adverse events such as illness or injury, a comprehensive debt discharge mechanism that is mindful of the perils of leaving consumers (especially those without viable resources) in a perpetual state of debt distress might be a more optimal safety net than restrictions on lending.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the estimation techniques and the data. It is possible that the estimations are impacted by a number of confounders that drive both current financial strain and health outcomes (e.g. changes in SES for young adults who move out of their original households to make their own or the variances in the financial impact of the different health conditions). For this reason, some cautious is necessary in interpreting the findings. As research in this area moves forward, longitudinal data collected specifically for the purpose of analysing the relationship between consumer finances and health would be helpful, especially in addressing the issue of timing between health events and financial strain. Research is also needed to target a particular illness (e.g. diabetes or TB) to observe its interaction with financial strain. This might present useful insights into policy-making towards people with that type of illness.

Acknowledgement

This is a comprehensively revised version of Chapter Four of Ralph A. Ssebagala’s PhD thesis submitted in November 2014 to the Doctoral Degree Board of the University of Cape Town. Greater detail on the study may be found in Ssebagala, RA. (2015). ‘The dynamics of consumer credit and household indebtedness in South Africa’. The author’s PhD was partially funded by grants to the CSSR and the UCT postgraduate funding office. The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions that greatly contributed to the improvement of this paper. A pre-peer review version of this work (Ssebagala, Citation2016a) can be found on the CSSR website as ‘CSSR Working Paper No. 391’ via the following link: http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/cssr/pub/wp/391.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Ralph A Ssebagala http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8200-5910

References

- Angela, J, 2008. Overindebtedness: last resort is personal insolvency. Federal Statistical Office Wissen, Germany. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Publications/STATmagazin/IncomeConsumptionLivingConditions/2008_01/PDF2008_01.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 7 June 2012.

- Backert, W, Ditmar, B, Götz, L & Katja, M. 2009. Bankruptcy in Germany: filing rates and the people behind the numbers. In J Niemi, I Ramsay & WC Whitford (Eds.), Consumer credit, debt and bankruptcy: Comparative and international perspectives, 273–88. Hart Publishing, Oxford.

- Betti, G, Dourmashkin, N, Mariacristina, R & Ya, PY, 2007. Consumer over-indebtedness in the EU: measurement and characteristics. Journal of Economic Studies 34(2), 136–56. doi: 10.1108/01443580710745371

- Blázquez, CM & Budría, S, 2015. The effects of over-indebtedness on individual health. Discussion Paper No. 8912. Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn.

- Braveman, PA, Catherine, C, Susan, E, Chideya, S, Marchi, KS, Metzler, M & Posner, S, 2005. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. Journal of the American Medical Association 294(22), 2879–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879

- Bridges, S & Disney, J, 2010. Debt and depression. Journal of Health Economics 29(3), 388–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.02.003

- Brix, L & McKee, K, 2010. Consumer protection regulation in low-access environments: opportunities to promote responsible finance. Focus Note No. 60. CGAP, Washington, DC.

- Brown, S & Taylor, K, 2008. Household debt and financial assets: evidence from Germany, Great Britain and the USA. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 171(3), 615–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2007.00531.x

- Collins, D, 2008. Debt and household finance: evidence from the Financial Diaries. Development Southern Africa 25(4), 469–79. doi: 10.1080/03768350802318605

- Collins, D & Leibbrandt, M, 2007. The financial impact of HIV/AIDS on poor households in South Africa. AIDS (London, England) 21(Suppl 7), S75–81. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300538.28096.1c

- D’Alessio, G & Lezzi, S, 2013. Household over-indebtedness: definition and measurement with Italian data. Occasional Paper No. 149. Bank of Italy, Rome.

- Del-Río, A & Young, G, 2005. The impact of unsecured debt on financial distress among British households. Working Paper No. 262. Bank of England, London.

- Doty, MM, Collins, SR, Rustgi, SD & Kriss, JL, 2008. Seeing red: the growing burden of medical bills and debt faced by US families. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 42(1164), 1–12.

- DTI-MORI, 2005. Over-indebtedness in Britain: A DTI report on the MORI financial services survey 2004. Department for Trade and Industry, London. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.berr.gov.uk/files/file18550.pdf Accessed 10 June 2012.

- Emami, S, 2010. Consumer overindebtedness and health care costs: how to approach the question from a global perspective. World Health Report Background Paper No. 3. World Health Organisation, Geneva.

- Falanga, MA, 2015. Over-indebtedness in the EU: from figures to expert opinions. European Financial Inclusion Network (March 2015). www.ecosocdoc.be/static/module/bibliographyDocument/document/004/3123.pdf Accessed 20 January 2018.

- Getter, DE, 2003. Contributing to the delinquency of borrowers. Journal of Consumer Affairs 37(1), 86–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2003.tb00441.x

- Guérin, I, Roesch, M, Venkatasubramanian, G & Kumar, S. 2013. The social meaning of over-indebtedness and creditworthiness in the context of poor rural South Indian households (Tamil Nadu). In I Guérin, S Morvant-Roux & M Villarreal (Eds.), Microfinance, debt and over-indebtedness. Juggling with money, 125–50. Routledge, Londres, London.

- Harris, B, Goudge, J, Ataguba, JE, McIntyre, D, Nxumalo, N, Jikwana, S & Chersich, M, 2011. Inequities in access to health care in South Africa. Journal of Public Health Policy 32(1), S102–23. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2011.35

- Himmelstein, DU, Thorne, D, Warren, E & Woolhandler, S, 2009. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. The American Journal of Medicine 122(8), 741–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.012

- Hurwitz, I & Luiz, J, 2007. Urban working class credit usage and over-indebtedness in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 33(1), 107–31. doi: 10.1080/03057070601136616

- Jacoby, MB & Holman, M, 2013. Managing medical bills on the brink of bankruptcy. Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics 10(2), 239–98.

- Keese, M, 2009. Triggers and determinants of severe household indebtedness in Germany. Ruhr Economic Papers No. 150. Department of Economics, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

- Kempson, E, 2002. Over-indebtedness in Britain. Department of Trade and Industry, London.

- Kim, KT, Wilmarth, MJ & Henager, R, 2017. Poverty levels and debt indicators among low-income households before and after the great recession. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28(2), 196–212. doi: 10.1891/1052-3073.28.2.196

- Knight, L, Roberts, BJ, Aber, LJ & Richter, L, 2015. Household shocks and coping strategies in rural and peri-urban South Africa: baseline data from the SIZE study in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of International Development 27(2), 213–33. doi: 10.1002/jid.2993

- Krumer-Nevo, M, Gorodzeisky, A & Saar-Heiman, Y, 2017. Debt, poverty, and financial exclusion. Journal of Social Work 17(5), 511–30. doi: 10.1177/1468017316649330

- Leibbrandt, M, Woolard, I & De Villiers, L, 2009. Methodology: report on NIDS Wave 1 - National Income Dynamics Study Technical Paper, (2009-1). http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/documents/technical-papers/108-nids-technical-paper-no1/file Accessed 10 January 2011.

- Lise, J & Seitz, S, 2011. Consumption inequality and intra-household allocations. The Review of Economic Studies 78(1), 328–55. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdq003

- Liu, K, 2014. Insuring against health shocks: health insurance, consumption smoothing and household choices. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/32f4/de862fbd4f1ce7b0a3367a5b1df9f443fb44.pdf Accessed 7 May 2015.

- Lyons, AC & Yilmazer, T, 2005. Health and financial strain: evidence from the survey of consumer finances. Southern Economic Journal 71(4), 873–90. doi: 10.2307/20062085

- Malghan, DV & Swaminathan, H, 2016. What is the contribution of intra-household inequality to overall income inequality? Evidence from global data, 1973-2013. https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1608/1608.08210.pdf Accessed 2 November 2016.

- Mayosi, BM & Benatar, SR, 2014. Health and health care in South Africa—20 years after Mandela. New England Journal of Medicine 371(14), 1344–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1405012

- Meier, S & Sprenger, C, 2010. Present-biased preferences and credit card borrowing. American Economic Journal of Applied Economics 2(1), 193–210. doi: 10.1257/app.2.1.193

- Meltzer, H, Bebbington, P, Brugha, T, Farrell, M & Jenkins, R, 2013. The relationship between personal debt and specific common mental disorders. The European Journal of Public Health 23(1), 108–13. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks021

- Meltzer, H, Bebbington, P, Brugha, T, Jenkins, R, McManus, S & Dennis, MS, 2011. Personal debt and suicidal ideation. Psychological Medicine 41(4), 771–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001261

- Micklitz, HW & Domurath, IM, eds. 2015. Consumer debt and social exclusion in Europe. Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Farnham.

- Ramsay, I. 2009. Wannabe wags and credit crunch binges: the construction of over-indebtedness in the UK. In J Niemi, I Ramsay & W Whitford (Eds.), Consumer credit, debt and bankruptcy: comparative and international perspectives, 75–89. Hart Publishing, Oxford.

- Seekings, J & Nattrass, N, 2008. Beyond ‘fluidity’: kinship and households as social projects. CSSR Working Paper No. 237. Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Ssebagala, RA, 2016a. Just not what the doctor ordered: poor health as a precursor to consumer debt distress in South Africa. CSSR Working Paper No. 391. Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/cssr/pub/wp/391 Accessed 20 December 2016.

- Ssebagala, RA, 2016b. What matters more for South African households’ debt repayment difficulties? Development Southern Africa 33(6), 757–73. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2016.1231055

- Ssebagala, RA, 2017. Relieving consumer overindebtedness in South Africa: policy reviews and recommendations. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 28(2), 235–46. doi: 10.1891/1052-3073.28.2.235