ABSTRACT

As South Africa contemplates another episode of public procurement legal reform, we trace the post-apartheid history of such efforts and consider critical issues moving forward. South Africa has over the last few decades followed the international trend of an expanding ‘contract state’. Public procurement is increasingly important to state operational and allocative concerns. South Africa’s public procurement regime is progressively configured into a centrally steered but decentralised organisational form. Inflected through domestic public procurement politics, however, the development of this organisational form has been truncated, with the establishment of only limited central steering capacity producing a public procurement regulatory regime which is weak, fragmented and incoherent, contributing to problems of state incapacity and corruption. In 2013 South Africa’s Minister of Finance announced a major push to reform South Africa’s contract state. The effort aims to better establish, locate and extend public procurement regulatory authority. It has begun to elaborate a centre-led, strategic and increasingly developmental procurement methodology. It is moving towards more flexibility, effectively an attempt to reduce rigidity in rules while building more robust and distributed disciplinary mechanisms, ones which take account of deficits in regulatory capacity and political will. We consider the potentials and pitfalls of these movements and suggest ways to optimise them.

KEYWORDS:

Public procurement, consisting in all processes through which states acquire their supply inputs, is significant to state capacity. It is inherently relevant to societal patterns of production and distribution. Public procurement, through these operative and allocative moments, can be, it actually unavoidably is, tied into a limitless range of specific public goals, from industrial development to environmental protection, from fiscal austerity to occupational health and safety. Public procurement, for this reason, is always entangled, more intimately than is ordinarily recognised, in the politics, the continuities and ruptures of broader societies.

Public procurement has become an increasingly prominent feature of these societies. Observers internationally have noted the rise of the so-called ‘contract state’ (e.g. Smith & Hague, Citation1971; Rhodes, Citation1994; Kirkpatrick & Lucio, Citation1996; O’Connor & Ilcan, Citation2005). The term describes states that, increasingly, discharge their functions not through their own personnel, organised into hierarchies, but in markets, through public procurement of private providers. Increasingly outsourcing has been promoted as a means toward operational efficiency, effectiveness, and flexibility. Public procurement has been systematically extended towards a deliberate moulding of allocative patterns in wider economies. These developments, although assembled from older material, have been encouraged, especially from the 1970s, by the worldwide fiscal and capitalist crises that marked that decade. They are part and parcel of consequent, epochal shifts in the organisational framework of global capitalism (e.g. Jessop, Citation1996; Castells, Citation2010).

South Africa has participated in these shifts. The present paper begins with an overview of the post-apartheid evolution of South Africa’s contract state. The history serves to emphasise its contemporary importance. It begins to elucidate its social and political causes. The history is also, moving into the second section, oriented toward a description of socially and politically embedded directions in contemporary public procurement law reform. The paper proposes for consideration both pitfalls and points at which these directions can be integrated into the improvement of South Africa’s public procurement regime.

1. Prefiguring contemporary public procurement reform in South Africa

It is characteristic for national public procurement regimes to be biased towards nationals within dominant class and status groups. In South Africa, during the long course of colonialism and apartheid, public procurement was biased towards white people. In post-apartheid South Africa, public procurement reform has engaged with issues of operational efficiency and effectiveness, but it has been concerned primarily with overturning white dominance in public procurement and in leveraging public procurement to overturn white dominance in society. Despite some expressions of discontent from white suppliers and status-conscious middle and lower classes, the important tensions have to do with different evaluations about how to configure public procurement to achieve broadly agreed objectives, evaluations partially structured along functional lines in the post-apartheid state and often associated lines of professional and structural differentiation in its social supports.

In this politics South Africa’s National Treasury occupies a central position. It is constitutionally empowered with regulating public procurement. It does so – together with an array of centrist politicians, international institutions, public management consultants, financial officers, and auditors – by subsumption under its organisationally dominant logic of public financial management. Public procurement regulation, in other words, is immersed in the tendentially autonomous realm of public finance, buffeted by but buffered from politics and operations, thereby detached from their realities and imperatives, these being disciplined and controlled to ensure procedural integrity and fiscal prudence. Others – including more redistributive politicians, state and consulting engineers, architects and development practitioners – in very different and in no sense allied ways, perceive in this mode of regulation a detached formalism, detrimental variously to operational substance, redistribution, and economic expansion. Chief among these other interests, and of growing importance, is that of black capitalism.

1.1. The black capitalist tendency in South Africa

The affinity of the politically dominant African National Congress (ANC) for black business formation is well-entrenched. It was from the outset under the influence of Booker T. Washington, an African-American ex-slave whose headline doctrine was that ‘At the bottom of education, at the bottom of politics, even at the bottom of religion itself there must be for our race, as for all races, an economic foundation, economic prosperity, economic independence’ (Washington in NNBL, Citation1915:74). Early leaders, such as John Dube, sometimes known as the Booker T. of Natal, and Pixley Seme spent time and corresponded with Washington. The party often attempted to emulate features of Washington’s National Negro Business League, establishing support vehicles to foster black-owned businesses that would be aligned to the ANC and serve to finance its activities (in Walshe, Citation1970:145, also 11–3). These sorts of ventures failed. In the ANC their underlying capitalistic inclinations were progressively sublimated through working class mobilisation, in the Marxist-Leninist language of unity of the nationally oppressed toward National Democratic Revolution.

Apartheid constraints meant that black capitalism more generally remained stunted, with a formally apolitical variant, also Washingtonian in outlook, propagating along the margins, associating in such forms as the 1964-founded National African Federated Chamber of Commerce (Nafcoc). Especially after the Soweto Uprising of 1976, the apartheid state and white corporates promoted such formations as a bulwark against unrest and socialist revolution (see Southall, Citation1980). In the course of the 1980s, black business associations, including the increasingly prominent Black Management Forum (BMF) under Don Mkwanazi, the so-called ‘godfather of black economic empowerment’, turned instead towards alignment with the then exiled ANC and the emerging post-apartheid order. In 1993 this produced the Mopani Memorandum of Understanding, which called for mechanisms of coordination between the ANC and black business. In 1996, to facilitate such coordination, black business organisations associated into the Black Business Council. In terms of the National Democratic Revolution, turning conspicuously pro-capitalist after the collapse of international socialism, the ANC positioned the ‘black bourgeoisie’, newly aligned or fostered from within party ranks, as ‘objectively important motive forces of transformation’ toward a liberal conception of the national democratic society (ANC, Citation1997).

Earlier ANC efforts toward fostering a supportive black capitalist class are today elaborated with the power of the post-apartheid state. In the wake of formally elaborated ANC policy, from its 1992 Ready to Govern onward, black capitalism became a central and growing feature on the post-apartheid statute book. A range of post-apartheid laws aimed to abolish apartheid restrictions on small business, expand financial inclusion, eliminate discrimination, and provide technical support and training. South Africa exhibits a highly concentrated economic structure, where most sectors are dominated by a small number of large, vertically-integrated, white-owned and -controlled firms – an effect of the mining-centred economy and its long years of apartheid-induced international isolation (Fine & Rustomjee, Citation1996). The post-apartheid state therefore also sought to regulate competitive conditions in these sectors and, beyond this, the easiest route and an avenue preferred by black business itself, it turned state regulation and contracting to the benefit of the previously disadvantaged.

The most sophisticated and expansive instrument along these lines came as the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) Act. It built upon earlier, private sector-led empowerment charters, standardising their measures. Engaging early criticism as to elite enrichment – not least from the ANC’s tripartite allies, the trade union federation Cosatu and the South African Communist Party (SACP) – it sought African national unity by incorporating the specific interests of black professionals, workers, and unemployed, along with other categories of oppressed and marginalised such as women and disabled people (see Southall & Tangri, Citation2006). The Act’s Section 9 codes of good practice apply B-BBEE indicators to the measurement of B-BBEE ratings, with a 2011 amendment requiring all private sector entities to get B-BBEE accreditation from a growing empowerment auditing industry. B-BBEE indicators measure contributions in categories including black ownership, management control, employment equity, skills development, enterprise development, socio-economic development, and preferential procurement. The Act’s Section 10 obliged organs of state to consider B-BBEE ratings when issuing licences, concessions and authorisations, or entering into partnerships, procurements, and sales. Businesses economically dependent on favourable state regulation or resource allocation were thereby incentivised to improve their B-BBEE ratings, partly by putting pressure on their suppliers to improve their B-BBEE ratings, which were therefore incentivised to put pressure on their suppliers, cascading in this way across the private economy. Procurement was thus a key thread running through state-driven black capitalist advance.

1.2. Post-apartheid public procurement reform

Public procurement reform occurred across a wider front. In 1993 national ANC leaders, already attentive to the redistributive importance of public procurement, had approached the World Bank to fund the work of the Procurement Forum, established in 1995 at the auspices of the Ministry of Public Works and including the Ministry of Finance. The Procurement Forum, supported by a technical Public Sector Procurement Reform Task Team, was mandated with designing South Africa’s post-apartheid public procurement regime. Thus, with the Ministry of Finance engaged with modernising the broader public finance regime, a junior ministry and department, with activist leadership in the persons of Minister of Public Works Jeff Radebe, Director-General Sipho Shezi, and Deputy Sivi Gounden, emerged as a champion of black capitalism, controlling and asserting wider regulation of South Africa’s considerable infrastructure budgets.

South Africa had historically operated a centralised procurement regime, with national functions vested in a State Tender Board, able to delegate to departments and other entities, together with alternative arrangements for security-related purchasing and state-owned enterprises. Provincial and local governments operated similar systems. Tender boards were generally composed of political representatives, state officials, and corporatised interests such as business, industry, and professional and other associations. These interests engaged directly with the allocation of tenders, each balancing the others to produce formally impartial distributions. They favoured open competitive tenders, but operated relatively loosely, regularly justifying departure from the lowest-priced rule. They leant strongly towards larger, better established businesses, a bias institutionalised in product specifications, norms, standards, rules, and procedures. In recognition of this inclination, the Procurement Forum’s interim strategy, articulated as a Ten-Point Plan in 1995, sought not only preferences, but also broader reform around unbundling large contracts, classifying building and civil engineering works to open opportunities on smaller, less complex contracts, and generally making it less costly for smaller suppliers to access information, make bids and get paid. The Procurement Forum also favoured decentralisation of procurement powers to procuring entities, a structural reform understood as necessary to breaking up large contracts and dissipate the power of the tender boards.

The 1996 Constitution’s section 216, dealing with Treasury control, read with section 217, the procurement clause, gave overarching regulatory authority over public procurement to the National Treasury. This followed a line going back to the 1909 South African Act and beyond into the British administrative tradition. In National Treasury globally prominent new public management thinking was taking root (see Cameron, Citation2009; Chipkin & Lipietz, Citation2012). The new public management stressed the twin objectives of giving state managers the freedom to manage and holding them accountable for results. What this meant in practice was that a broad range of managerial powers and functions were to be decentralised and responsibility for their discharge aligned in the offices of departmental and agency heads, styled as accounting officers and authorities. Central tender boards, by removing important powers from the control of administrative heads, limited managerial prerogative and thereby confused lines of accountability. So, on this reasoning, National Treasury thinking meshed with the Department of Public Work’s interest in decentralisation, an approach adopted in the 1997 Green Paper on Public Sector Procurement Reform, released jointly by both.

The Green Paper coupled decentralisation with extensive central regulation, the latter to be undertaken by a National Procurement Compliance Office. The Procurement Compliance Office would be responsible for establishing uniform standards and documentation; receiving reports and complaints; auditing, investigating and researching the compliance and performance of procuring entities; providing support and enforcing compliance; developing information systems and ensuring communication and liaison across the procurement system (Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Public Works, Citation1997). The Green Paper, however, released for public discussion, never graduated into an authoritative White Paper. Decentralisation was not matched by the robust central steering capabilities envisaged in the Green Paper as the Procurement Compliance Office.

1.3. The truncated evolution of public procurement regulation

National Treasury itself absorbed the State Tender Board and retained existing public procurement regulatory functions. These followed an exceedingly complicated dispersal across a number of its divisions. Its residual Specialist Functions took the lead, but without significant analytical and enforcement capacities. These capacities could be found scattered across the Office of the Accountant-General, Intergovernmental Relations, and Assets and Liabilities Management. National Treasury’s tendential reduction of public procurement to general public financial management was in this way written into its organisational chart. Public procurement professionals failed to find adequate expression in departmental divisions concerned with public procurement mainly from a financial perspective. Reflectively, the general and capacious provisions of section 217 of the Constitution – providing for procurement in accordance with a system which is fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective – did not find expression in a single statutory bridge into implementation, but a range of separate, fragmented, and increasingly inconsistent laws (see World Bank, Citation2003).

The early Treasury Control Bill, stumbling on the assertion of important constitutional and administrative differences between the national and provincial ‘public service’ and local government, was split into what would become the 1999 Public Finance Management Act (PFMA) and the 2003 Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA). These, principally dealing with public financial management, decentralised procurement powers to procuring entities. They did so on the basis of mandatory structures and procedures that, in a context of political distrust of expertise and limited specialist purchasing skills, have worked to remove procurement powers from technical, end-user professionals, locating them instead with financial officers, new supply chain management units, and bid committees that have checked professional power while tending to shape public procurement into a financial-clerical function distant from operational needs.

In 2000, the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act (PPPFA), chasing a 4 February constitutional deadline, was a rushed affair and exhibited parallel dynamics. The Act established preferences through a point-based system for the adjudication of tenders, with ratios of price to preference of 90:10 or 80:20 for contracts above or below the then threshold of R500 000. The white-dominated South African Chamber of Business (SACOB), together with political representatives such as the Democratic Alliance (DA), accepted the framework but sought temporal limitations, pushing for the legislation to fall away or be revised after a statutorily defined period. Real opposition came, instead, from black business and aligned officials and professionals, who complained that the points system amounted to excessive restraint on black empowerment and an actual reversal of trends already achieved in some parts of the state. The points system ignored differences in the ease with which preferences could be attained across sectors and items and it undercut administrative experimentation in more dynamic approaches. Innovative mechanisms – developed by progressive project managers, architects, and civil engineers – that incentivised competition between suppliers in expanding black participation in sub-contracts and other benefits, were suppressed not only by the points system, but also from 2003 by the B-BBEEA, which applied the points system not to discrete bids but to whole, B-BBEE rated firms.

Developmental initiatives, such as the Competitive Supplier Development Programme of the Department of Public Enterprises, and the Local Content Programme of the Department of Trade and Industry, were similarly effaced (Cawe, Citation2015). In 2011, furthermore, the Pietermaritzburg High Court, in Sizabonge Civils v Zululand District Municipality, held that the PPPFA excluded functionality as an adjudication criterion. From then on only price and preference could be incorporated into points, undermining elementary practice in such sectors as consulting services and construction.

Behind all this lay thwarted intentions, borne by organs of state and other actors, often with specific policies and statutes that are so many efforts to supplement and workaround National Treasury regulation. Increasingly incoherent, and as National Treasury itself responded to emerging issues in ad hoc and unsystematic ways, by 2014 there were no less than 22 statutes dealing with public procurement in a direct and significant way, with subordinate legislation bringing a total of approximately 85 distinct pieces of legislation. By this point National Treasury officials and consultants describe dealing with a public procurement legislative landscape that was overly fragmented and often inconsistent. They reported significant difficulty in determining the complete set of instruments applicable to any particular case, with overlap and duplication also producing uncertainty as to which instruments to follow (Arendse, Citation2013; Malinga, Citation2014; Quinot, Citation2014). In terms of simple compliance, moreover, by the 2010s it was clear that the system was coming undone.

1.4. The expansion and corruption of the contract state

Since 1994 the South African state has significantly expanded the scope of functions that are contracted out. Policy design and analysis processes are pervasively outsourced. Consultants often finalise basic documents such as Integrated Development Plans and financial statements in preparation for audits. They tend to drive major administrative reform initiatives. In interview, officials, administrative and technical, report that they spend more and more time in the specification and management of contracts and that even the capacity to perform these functions has been hollowed out by excessive recourse to contracting, which excludes personnel from implementation work and thereby undermines broader career prospects. Indeed, the contracting function itself is often contracted out, to increasingly prominent purchasing management units.

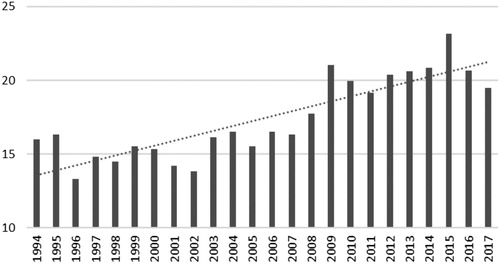

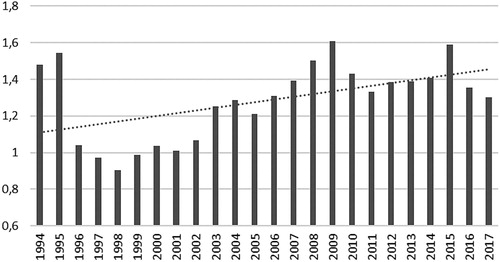

The growth of the contract state can also be measured quantitatively. The ratio of total public sector procurement expenditure to employee compensation suggests an increasing weight of public procurement in state operations. In , the initial decline of this ratio is consistent with expectations. The incoming ANC government underspent as it restructured the state and reprioritised its project portfolio. The new government also increased wages, for instance in 1996 by between 29% and 35% for grades 1–6 of the public service (see Adler, Citation2000). From this point, as outsourcing gained increasing legitimacy with the new public management, as administrative capacity declined with processes of politicisation and rapid turnover in personnel, as new interests to do with class formation, party finance, and patronage formed around public contracting, and as data becomes more reliable, procurement to compensation rebounds from a ratio of 0.90 in 1998, to a height of 1.61 in 2009, then 1.31 in 2017. Consequently, procurement expenditure has become an increasingly prominent feature of the South African economy. From 1998 to 2017, shows a significant, five-percentage point increase in procurement expenditure as a percentage of GDP.

Figure 1. Ratio of public sector procurement expenditure to employee compensation. SARB financial statistics throughout. Procurement expenditure is calculated by adding purchases of goods and services and purchases of non-financial assets. Total public sector is calculated, according to the SARB Institutional Sector Classifications, by adding consolidated general government to non-financial and financial public corporations.

By 2017 financial statistics indicate that public sector procurement expenditure topped R963 billion. This issued from 1022 distinct procuring entities. Each of these exhibited various degrees of internal delegation of procurement operations, with for instance provincial departments of health and basic education devolving some contracting powers to tens of thousands of public hospitals and schools. These entities conclude, with well over a hundred thousand registered suppliers, over a million contracts annually. As Pravin Gordhan, then Minister of Finance, noted in 2013, ‘there is very little visibility of all these transactions’ (Gordhan, Citation2013).

Irregularity and much denounced ‘corruption’, are widely in evidence. The Auditor General of South Africa (AGSA) repeatedly stresses that irregularity is most evident in public procurement. For 2016/17 AGSA reported that under the PFMA 89% of irregular expenditure occurred in procurement,Footnote1 while under the MFMA the comparable figure was 99% (AGSA, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The result of R69 billion in irregular expenditure includes amounts uncovered in this financial year and multi-year contracts concluded in previous years. In this year 86% of departments, 61% of public entities, and 91% of municipalities received findings around procurement. The relative scale of irregularity in public procurement reflects the fact that a number of potentially remunerative regulatory functions do not involve expenditure, but it is also indicated by the expansion of the contract state, the sums involved, and the inherent difficulty of regulating procurement practices, where sharp trade-offs occur between rule-following and efficiency.

Irregularity indicates a breakdown in the control environment. It is, of course, not corruption. It is common for irregularity to issue from causes other than corruption. It is relatively easy to follow public procurement rules while corrupt. Still, as a function of its relevance to projects of class formation, party financing, and patronage distribution, and the blurring of the lines between public and private that these projects involve, most of South Africa’s corruption scandals have involved public procurement. The public procurement regulatory regime has been problematic in this respect. National Treasury’s Specialist Functions have remained under-capacitated. The National Treasury’s then Director-General Lungisa Fuzile stated in 2015 that ‘Traditionally, SCM [supply chain management] has been misunderstood and undervalued’. The PFMA and MFMA never specified National Treasury’s regulatory and enforcement powers in a manner tailored to public procurement. Legal questions continue to undermine, for instance, National Treasury’s attempts to suspend and invalidate irregular procurement processes.

The department was also partly undercut by politics, displaying a pronounced reticence in enforcement where this would involve prosecution of powerful political actors in the ANC. National Treasury has sought to depoliticise the procurement function in procuring entities, for instance by removing politicians from participation in bid committees and prohibiting political interference in procurement decision-making. Politicisation, however, has occurred in any case through the human resources function, over which Treasury has no direct legal authority. Politicisation of human resourcing, while intended initially to ensure political control over an administration deemed to have sympathies with apartheid and reactionaries, by giving politicians control over appointment, promotion and dismissal, enables their use of these powers to bridge and erode administrative checks and balances, therefore facilitating coordination of corrupt activities. These dynamics are prevalent across the regulatory and resource allocation functions of the state, but they are especially prominent in public procurement.

2. Contemporary public procurement law reform in South Africa

The antecedents of the present reform drive stretch back two decades. In 1998 the Black Business Council established the Black Economic Empowerment Commission, then chaired by now president Cyril Ramaphosa. Reporting in 2001, its participants expressed discontent with National Treasury’s restrained approach to preferential procurement (BEECom, Citation2001). Still fostered under its restrained provisions, black business has become an increasingly powerful agent pushing for public procurement reform.

Public discontent with corruption and poor service delivery, as well as fiscal concerns with bloated procurement expenditure, also exercised minds at ANC policy conferences (see Cronin, Citation2012), the National Planning Commission (Citation2012), and in the National Treasury itself. Earlier, National Treasury had led the establishment of a Multi-Agency Working Group (MAWG) to investigate procurement fraud and corruption, with the South African Revenue Service, the Financial Intelligence Centre, the Auditor General, the Special Investigating Unit, and the Department of Public Service and Administration. MAWG was divided into two sub-groups, one concerned with preventative measures and one with enforcement, both increasingly concerned with reform. Before National Assembly committee, Freeman Nomvalo, Accountant General, argued that looting of public procurement had become a risk to fiscal sustainability (National Treasury, Citation2012). In his February 2012 Budget Speech Minister Gordhan, following this reasoning, announced the establishment of the Office of the Chief Procurement Officer (OCPO). In an OCPO business case drafted by July, the Office of the Accountant-General (OAG) noted its own limited capacity to engage with emerging issues (OAG, Citation2012). The OCPO was established around a vision of informational modernisation, with information and communication technology mobilised behind cutting edge procurement practice to ensure procedural integrity and drive efficiencies. It occupied the space within National Treasury of the old Specialist Functions. Organisational restructuring moved the old Division’s Chief Directorate: Financial Systems over to the OAG but kept for the OCPO its existing chief directorates responsible for transversal contracting and for policy, norms, and standards. The newly minted unit then further accrued functions mirroring for procurement those of the more robustly regulatory OAG, including new chief directorates for Governance, Monitoring and Compliance; Information and Communication Technology; Client Support; and Strategic Procurement (OAG, Citation2012; OCPO, Citation2014).

As the OCPO began to assert its regulatory role, questions emerged as to the strength and specificity of its legal powers. The OCPO was experiencing resistance from other organs of state on grounds of constitutionally-enshrined administrative autonomy, indicating continuity rather than change from the relatively weak and ad hoc role played by Specialist Functions. In his 2013 Budget Speech, therefore, Gordhan announced a wider reform effort, with unprecedented acknowledgment of the political challenges involved:

Let me be frank … While our ablest civil servants have had great difficulty in optimising procurement, it has yielded rich pickings for those who seek to exploit it. There are also too many people who have a stake in keeping the system the way it is … This is going to take a special effort from all of us in Government, assisted by people in business and broader society. (Gordhan, Citation2013)

2.1. Establishing, locating and extending public procurement regulatory authority

The new round of public procurement legal reform aims to provide a single legislative bridge between the Constitution and procuring entities. A new statute would represent under the Constitution the chief legal instrument providing for the regulation of public procurement across government, overriding other public procurement legislation. The overall intention will be to unify and cohere the currently fragmented and inconsistent legal and regulatory universe.

To achieve this on an ongoing basis the statute will provide for the formal establishment of a new public procurement regulatory authority, currently structured as the OCPO, as the chief regulator of public procurement. It will be empowered in ways that are more closely tailored to the requirements of public procurement regulation, including powers to issue mandatory frameworks, norms and standards; to set information technology requirements; to require the use of standard procurement documents; to establish data retention and reporting requirements; to receive and resolve complaints; to conduct reviews and investigations of the procurement systems of procuring entities; to impose administrative remedies including the suspension of processes and cancellation of contracts; to suspend and debar suppliers; to require organs of state to opt in to transversal contracts; to require and promote transparency and public participation; and to establish and enforce professional requirements on procurement officials. The need for such a new, overriding regulatory authority is widely conceded. Debate centres on the issue of where to locate the relevant powers institutionally.

The first concern is prefigured in the 1997 Green Paper and its Procurement Compliance Office. The Black Economic Empowerment Commission, given its own discontent with National Treasury regulation, called for a National Procurement Agency subject to the oversight of the Minister of Trade and Industry (BEECom, Citation2001). Questions of institutional location were raised again at the time of the operation of the OCPO by a commissioned expert study into the feasibility of public procurement legislative reform (Quinot, Citation2014). The study argued that current international best practice in public procurement reform would tend to favour establishment of the OCPO as a national public entity, outside of the public service, unattached to any particular ministry, preferably accountable directly to Parliament and subject to special rules of appointment and dismissal. The attendant argument is that independence from politics and from the procurement operations of any department is necessary in order to ensure effective, objective and impartial discharge of regulatory functions.

These options can’t be argued conclusively. Organisational restructuring decisions are notoriously unavailable for evaluation on any single scale (Simon, Citation1946; Braybrooke & Lindblom, Citation1963). It is not possible to provide definite answers about the trade-off between, say, the substantive democratic importance of political control and the presumed procedural integrity of institutional independence. The intractable nature of organisational redesign dilemmas is part of the reason why efforts in this direction should be predicated on the identification of compelling organisational structural problems. In South African this has not yet happened. In the first instance, it is not clear whether any movement of a public procurement regulator beyond National Treasury will be constitutionally feasible. Chapter 13 of the Constitution gives control over fiscal and public financial matters, including public procurement, to the National Treasury. In terms of Section 5 of the PFMA, the National Treasury includes the Minister of Finance. At most, to fit unambiguously within these clauses, an attempt at independence might extend to legislative establishment of a public entity accountable to the Minister of Finance. Efforts to move the locus of public procurement regulation beyond the National Treasury will invite legal challenges to its decisions.

Leaving aside the constitutional issue, whether such an establishment option is desirable depends on the interests that underlie the desire. Those who rank procedural integrity highly, therefore favouring independence, should recognise the distinction between formal independence and de facto independence. Formal independence consists in legal and formal organisational arrangements that limit certain forms of control by elected politicians and others. De facto independence concerns the extent to which organisations exercise actual autonomy in their day to day regulatory activities. Quantitative and qualitative research indicates that formal independence is relevant to, but not necessary or sufficient for, de facto independence (Maggetti, Citation2012). It is not uncommon that formal mechanisms are established, ostensibly providing for independence, but precisely for the purpose of assuming political control. De facto independence, on the other hand, is best explained sociologically, in terms of the extensive literature on the phenomenon of bureaucratic autonomy (classically, Weber, Citation1922; Bendix, Citation1945). The literature notes the importance of organisational design, but routinely asserts that such autonomy is more powerfully a function of political and organisational sociology. Politicians are dependent upon the expert knowledge of administrative officials to perform administratively sophisticated operations. The consequent power of administrative officials is enhanced to the extent that they have scarce knowledge, so are more difficult to replace, and to the extent that such knowledge is necessary to ensuring the provision of goods in which powerful social actors have an intense and urgent interest. These various factors are augmented by solidary networks, between officials and between officials and other social actors, which can mobilise to make it immediately politically costly to interfere in the rational provision of public goods.

These criteria, variously elaborated (Evans, Citation1995; Carpenter, Citation2001), including in literature on regulatory agencies (Maggetti, Citation2012), describe National Treasury well. Certainly, no legally-contrived, formally independent agency could hope to achieve the wide-ranging defences that this institution has periodically thrown up. These defences, then alternatively, raise the issues of political control and responsiveness often opined by black business, developmentalists in the departments of Trade and Industry and Public Enterprises, and a range of operational procurement practitioners. Their arguments, it is suggested below, elide a range of significant developments in National Treasury’s procurement policy.

2.2. Centre-led, strategic and developmental procurement methodology

The second line running through public procurement legal reform has to do with procurement methodology. It is concerned with who purchases and how. South Africa’s public procurement regime, historically, has tended to cycle between processes of centralisation and de-centralisation of purchasing powers. Generally disruptive of procurement capacitation and institutionalisation, these cycles are produced, in part, by the sorts of intractable dilemmas thrown up by incommensurable values in the institutional location decisions discussed previously. Centralised public procurement regimes create bottlenecks, they have difficulty specifying the particular needs of end-user organs of state, but they support standardisation and they allow the state to use its purchasing power to drive cost-savings and develop economies of scale in the broader economy. Decentralised public procurement regimes achieve the opposite. New information technology, important to the OCPO’s reform vision, facilitates optimisation of such values by more fine-grained processes of centralisation-decentralisation, across phases in the procurement process and commodities.

The OCPO has involved itself in the elaboration of a new centre-led approach, with a central supplier database and e-tender portal allowing for central registration of suppliers and information dissemination, with transversal contracting moving towards the establishment of framework contracts and e-procurement services which in the OCPO’s vision will begin to approximate an internal-to-government ‘amazon.com’ electronic commerce platform. Legally, what this requires is broader powers to centralise discrete moments of procurement processes.

The OCPO is also involved in the elaboration of a wider approach to strategic procurement. Strategic procurement involves a more pragmatic, flexible, and differentiated approach to procurement methodology. Drawing on Kraljic (Citation1983), as well as the New Zealand example of strategic procurement in the public sector, the National Treasury (Citation2015a) is beginning to implement a methodology which recognises the importance of ensuring value added across the procurement process, from project initiation, market research and specification, through to contract and relationship management and review. What this amounts to is a significant departure from the present public sector norm of annual competitive tendering, enjoining organs of state to develop more strategic classifications of commodities, allowing for a more differentiated approach which includes the building of relationships with suppliers of high value and high risk commodities. The approach opens out into a recognition of the importance of functionality as an adjudication criterion. It includes exploration of new forms of procurement such as strategic sourcing, electronic reverse auctions, and innovation partnerships. The cumulative effect of these changes will be to reduce red-tape, facilitating efficiency and effectiveness in allowing procuring entities the room to adjust purchasing methodology flexibly to suit their requirements.

The movement is sensible. Integrity watchdogs may balk at the loosening of rules in a context of pervasive corruption. It is worth noting, however, that at present irregularity is defined around rules which generate inefficiency and ineffectiveness in procurement operations. Changing them doesn’t accept ‘corruption’, it redefines corruption, around more efficient and effective ones, in recognition of the sociological reality that procurement, in the private sector and (in fact) the public sector, relies extensively on more relational methodologies which often carry significant economic advantages. Long-term relationships, appropriately disciplined, tend to reduce risks, allowing for the consolidation of mutual expectations, moral community, trust and information symmetries which serve to reduce transaction costs. Long-term relationships can also invoke long-term perspectives and give time to the fostering of private sector capacities.

These shifts in National Treasury go far in the direction called for by National Treasury opponents. Furthermore, the department is committed, under pressure from the Black Business Council and developmental interests in the Department of Trade and Industry and the state-owned enterprises, to loosening the rigid PPPFA, moving the points system from statute into subordinate legislation on the view that more responsiveness and flexibility is needed than time-consuming parliamentary amendments can provide.

2.3. From rigid rules to more robust and distributed disciplinary mechanisms

Such an approach to procurement methodology is dependent, crucially, upon discipline. We have noted that this is a serious problem for the present regime. Restrictive rules, however, do not on their own resolve this problem. They simply restrain those who attempt to follow them, with significant costs in terms of efficiency and effectiveness, producing professional incentives toward circumvention. On the other hand, a serviceable political position means that those who have no intention of following the rules or serving the public are able to avoid enforcement. Contemporary law reform in the public procurement regime ultimately proposes to shift the burden of ensuring integrity from restrictive rules toward a commitment to expanding mechanisms of oversight and enforcement, through better tailored regulatory powers, transparency, civil society participation, support and capacity-building, professionalisation and dispute resolution.

The push will include better tailored regulatory powers, such as the suspension and termination of procurement processes, the cancellation of contracts, the possibility of central debarment of suppliers, and the establishment of standards for price and specifications. National Treasury is itself, however, often sensitive to political and organisational constraints on its enforcement efforts, so for this reason regulatory reform also needs to cover gaps in political will and enforcement capacity. Of particular interest here is opening regulation up to public involvement, through transparency and participation provisions.

Existing transparency provisions are not working. Rules for tender advertisement, disclosure of evaluation criteria, and publication of awards are frequently breached. They are in any case too narrow to ensure effective public oversight. Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) requests are commonly stymied by administrations. Bids and related documentation are often kept confidential, for instance on grounds of protecting business’ proprietary information. Some of these concerns are being addressed through OCPO’s e-tender portal and central supplier database, which offer efficient mechanisms for reporting and publication. With advances in information technology, there is little reason why such efforts shouldn’t be expanded to include some movement toward mandatory publication of annual procurement plans, of market research, specifications, written justifications for deviation from normal procurement methodologies, requests for clarification and answers, contract performance standards and achievement against these, and contract variations.

Transparency and public participation, of course, are no panaceas. Their success is heavily dependent upon context (see Gaventa & McGee, Citation2013), including the extent to which citizens themselves suffer or benefit from corruption and the broader existence of actors willing and empowered to punish transgressions (Brunetti & Weder, Citation2003; Olken, Citation2004). Transparency, furthermore, illuminates decision-making processes for those concerned with integrity and for those concerned with malfeasance, who find it easier to bribe and coerce relevant decision-makers (Bac, Citation2001). In our own experience, professional public officials in South Africa are often ill-capacitated to perform due diligence, overworked and therefore wary of honest mistakes becoming scandals with significant consequences for their personal and professional lives. They are also often already abused by disappointed tender-seekers. More transparency, without other safeguards, will disincentivise participation in such structures as bid evaluation and adjudication committees, losing skills critical to good decision-making. It will also slow processes, by incentivising often undue official pedantry and proliferating public challenges. Maximalist approaches to transparency, as suggested by civil society organisations in South Africa’s procurement reform process, should be tempered by these sorts of considerations. It may be unwise, for instance, to mandate standing public identification of officials involved in procurement processes.

A further way around some of the unintended consequences of transparency is to reinforce public involvement by incentivising whistleblowing and private investigation, in a way that focuses less on criminal liability than on civil damages, through a qui tam provision. First developed in England in the 1200s, the qui tam lawsuit was for centuries a principal enforcement tool for various English laws. It was then put on a statutory basis in the United States during the Civil War, under the federal False Claims Act, which sought to restrain corruption proliferating around war supplies. Qui tam lawsuits provide a reward (a bounty) for private action enforcing a public claim. The remedy unites those with inside information and those with the legal power and incentive to use that information. Whistle-blowers, termed ‘relators’, that have information, beyond already publicly available information, on a fraud perpetrated against the state approach law firms specialising in qui tam suits. These can file with, say, the Department of Justice, confidentially from the public and the defendant, giving the government a period to decide whether it wants to take on the suit. If the government opts to do so, taking on associated costs, then in the event of success, fraud being proven on a balance of probabilities, the relator would receive a stipulated percentage of damages, say 15%. If the state does not take on the suit, the relator can proceed to court and receive a higher percentage of the damages (Braithwaite, Citation2008:66–73).

Penalties can be used to discourage frivolous and vexatious proceedings. Qui tam suits need not stall existing procurement processes. Furthermore, incentives increase with damages, meaning that qui tam favours enforcement for larger contracts which have significant bearing upon the interests of the state. International experience also suggests that qui tam provisions can provide the material underpinnings for more densely elaborating networks between state enforcers, whistle blowers and NGOs and related interests in good governance (Braithwaite, Citation2008:66–73). Qui tam provisions also plausibly serve to seed distrust within illicit networks, disrupting efforts to coordinate corrupt activities. While there are nuanced issues to be covered in introducing such a remedy into South African law, such a mechanism deserves careful consideration and may prove to be a powerful tool.

3. Conclusion

The impetus toward reform in this crucial field involves a mutual escalation of attention from a range of distinct, interacting but potentially inconsistent interests. Fiscal sustainability, procedural integrity, industrial development, redistribution, service delivery and often illicit self-enrichment all figure. All have moments of uneasiness with each other. The task of reformers is to rationalise these tendencies into an improved public procurement regime.

Since the current regime of procurement regulation can best be described as in a state of incomplete movement toward a centrally steered but decentralised procurement regime, we advocate pulling that regime through to a state of completion. National Treasury provides, we would argue, an indispensable vehicle for cohering and disciplining South Africa’s contract state. Proposals to move public procurement regulatory authority beyond National Treasury ignore vital legal, organisational and sociological realities. National Treasury’s approach to centre-led and strategic procurement accommodates the main concerns emerging from other significant actors, while at the same time it enables genuinely redistributive and developmental efforts which can be more thoroughly explored. Finally, as the regulatory regime approaches completion, we advocate continuing to network and embed that regulation in society, through a prudent approach to transparency and public participation, recognising and working with public procurement as a critical feature of wider political and social processes.

Disclosure statement

The authors worked through PARI in 2016 as consultants for South Africa’s National Treasury in the area of public procurement reform. National Research Foundation (South Africa) and the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies (University of the Witwatersrand).

ORCID

Jonathan Klaaren http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8732-3771

Notes

1 Referred to in AGSA reports as ‘supply chain management’ or ‘procurement and contract management’.

References

- Adler, G (Ed.), 2000. Public service labour relations in a democratic South Africa. Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg.

- AGSA (Auditor General of South Africa), 2017a. Consolidated general report on national and provincial audit outcomes. http://www.agsa.co.za/Portals/0/Reports/PFMA/201617/GR/AG%20PFMA%202017%20Web%20SMALL.pdf.

- AGSA (Auditor General of South Africa), 2017b. Consolidated general report on the local government audit outcomes. http://www.agsa.co.za/Portals/0/Reports/MFMA/201617/GR/MFMA2016-17_FullReport.pdf.

- ANC (African National Congress), 1997. Strategy and tactics as adopted at the 50th national conference. http://www.anc.org.za/content/anc-strategy-and-tactics-adopted-50th-national-conference.

- Arendse, P, 2013. Project report: Comparative benchmark research on international public procurement legal frameworks. National Treasury Document. Personal Archive.

- Bac, M, 2001. Corruption, connections and transparency: Does a better screen imply a better scene? Public Choice 107(1–2), 87–96.

- BEE (Black Economic Empower Commission), 2001. Report of the black economic empowerment commission. Skotaville Press, Johannesburg.

- Bendix, R, 1945. Bureaucracy and the problem of power. Public Administration Review 5(3), 194–209.

- Braithwaite, J, 2008. Regulatory capitalism: How it works, ideas for making it work better. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

- Braybrooke, D & Lindblom, CE, 1963. A strategy of decision. Free Press, New York.

- Brunetti, A & Weder, B, 2003. A free press is bad news for corruption. Journal of Public Economics 87(7), 1801–24.

- Cameron, R, 2009. New public management reforms in the South African public service: 1999–2009. Journal of Public Administration 44(1), 910–42.

- Carpenter, DP, 2001. The forging of bureaucratic autonomy: Reputations, networks, and policy innovation in executive agencies, 1862–1928. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Castells, M, 2010. The information age: Economy, society, and culture. Volume I: The rise of the network society. 2nd edn. Blackwell, London.

- Cawe, A, 2015. Programmatic procurement: A political economy review of the transnet freight rail competitive supplier development programme. MA, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Chipkin, I & Lipietz, B, 2012. Transforming South Africa’s racial bureaucracy: New public management and public sector reform in contemporary South Africa. Public Affairs Research Institute, Long Essay 1.

- Cronin, J, 2012. “We’ve been structured to be looted”- Some reflections on the systemic underpinnings of corruption in South Africa. Paper Presented at the Symposium on International Comparative Perspectives on Corruption, Public Affairs Research Institute and Innovations for Successful Societies, held at the University of the Witwatersrand.

- Evans, PB, 1995. Embedded autonomy: States and industrial transformation. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Fine, B & Rustomjee, Z, 1996. The political economy of South Africa: From minerals energy complex to industrialization. Hurst & Co, London.

- Gaventa, J & McGee, R, 2013. The impact of transparency and accountability initiatives. Development Policy Review 31, s3–s28.

- Gordhan, P, 2013. Budget speech in the South African national assembly.

- Jessop, B, 1996. Post-fordism and the state. In Greve B (Ed.), Comparative welfare systems. MacMillan, Basingstoke.

- Kirkpatrick, I & Lucio, MM, 1996. Introduction: The contract state and the future of public management. Public Administration 74(1), 1–8.

- Kraljic, P, 1983. Purchasing must become supply management. Harvard Business Review 61(5), 109–17.

- Maggetti, M, 2012. Regulation in practice: The de facto independence of regulatory agencies. ECPR Press, Colchester.

- Malinga, H, 2014. Policy statement on public procurement legislative reform in South Africa. National Treasury Document. Personal Archive.

- Ministry of Finance & Ministry of Public Works, 1997. Green paper on public sector procurement reform in South Africa. Notice Number 691 of 1997. Government Gazette, 691 (17928), 14 April.

- National Negro Business League, 1915. Annual report of the sixteenth session and the fifteenth anniversary convention. African Methodist Elementary Sunday School Union, Nashville.

- National Planning Commission, 2012. National development plan 2030: Our future – make it work. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/NDP-2030-Our-future-make-it-work_r.pdf.

- National Treasury, 2012. National treasury briefing to the portfolio committee on public service and administration as well as performance monitoring and evaluation, 28 August. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/14763/.

- National Treasury, 2015a. Public sector supply chain management review. http://www.treasury.gov.za/publications/other/SCMR%20REPORT%202015.pdf.

- National Treasury, 2015b. National treasury briefing to the standing committee on public accounts, 12 August. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/21303/.

- OAG (Office of the Accountant General), 2012. Business case for the office of the chief procurement officer. National Treasury Document. Personal Archive.

- O’Connor, D & Ilcan, S, 2005. The folding of liberal government: Contract governance and the transformation of the public service in Canada. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 30(1), 1–23.

- OCPO (Office of the Chief Procurement Officer), 2014. Establishment report. National Treasury Document. Personal Archive.

- Olken, BA, 2004. Monitoring corruption: Evidence from a field experiment in Indonesia. National Bureau of Economic Research, Washington, DC.

- Quinot, G, 2014. An institutional legal structure for regulating public procurement in South Africa. Research report on the feasibility of specific legislation for National Treasury’s newly established Office of the Chief Procurement Officer. http://africanprocurementlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/OCPO-Final-Report-APPRRU-Web-Secure.pdf.

- Rhodes, RAW, 1994. The hollowing out of the state: The changing nature of the public service in Britain. The Political Quarterly 65(2), 138–51.

- Simon, HA, 1946. The proverbs of administration. Public Administration Review 6(1), 53–67.

- Smith, BLR & Hague, DC, 1971. The dilemma of accountability in modern government: Independence versus control. Palgrave MacMillan, London.

- Southall, R, 1980. African capitalism in contemporary South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 7(1), 38–70.

- Southall, R & Tangri, R, 2006. Cosatu and black economic empowerment. In Buhlungu, S (Ed.), Trade unions and democracy: Cosatu workers’ political attitudes in South Africa. HSRC Press, Pretoria.

- Van der Westhuizen, C, 2015. Monitoring public procurement in South Africa: A reference guide for civil society organizations. International Budget Partnership. https://www.internationalbudget.org/publications/monitoring-public-procurement-south-africa-guide/.

- Walshe, P, 1970. The rise of African nationalism in South Africa: The African national congress, 1912–1952. C Hurst, London.

- Weber, M, 1922. Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. Roth, G & Wittich, C (Trans.) University of California Press, Berkeley.

- World Bank, 2003. South Africa country procurement assessment report. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/docsearch/report/25751.

- World Bank, 2016. Benchmarking public procurement 2016: Assessing public procurement in 77 economies. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/504541468186536704/Benchmarking-public-procurement-2016-assessing-public-procurement-systems-in-77-economies.