ABSTRACT

This paper reviews the domestic political and legislative context surround biofuels initiatives to highlight what opportunities exist for establishing a biofuels trade network between South Africa (as an anchor market) and its neighbours, specifically in Zambia and Mozambique. By analysing global developments in major biofuel importers, reasons for policy inertia in South Africa, and recent experiences with biofuels investments, we suggest that the likelihood for a regional biofuels market developing is slender without addressing land-related challenges in producer countries and revising South Africa’s domestic legislation.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

There has been a long-standing interest in leveraging the perceived abundant land resources in sub-Saharan African countries to produce feedstocks for biofuels (Searle & Malins, Citation2015; Souza et al., Citation2015). From a national economic perspective, proponents argued that domestic production can reduce the dependence on the imports of fossil fuels for the transport sector, which saddle oil importers with high bills during periods of high oil prices (Kohler, Citation2016). These economic arguments underpinned the early Sub-Saharan adopters of biofuels (e.g. Malawi, Zimbabwe) as well as those countries that introduced mandates more recently.

Policy measures in the global North to tackle climate change through reducing emissions in transport fuel, and trade agreements granting several countries preferential access to EU markets further encouraged project developers to initiate biofuels projects to produce carbon credits (De Keyser & Hongo, Citation2005; UNCTAD, Citation2009).

Finally, biofuel feedstock development has been proposed as a means of contributing towards rural development and poverty reduction as it requires investment in infrastructure and creates jobs. Modelling studies have found that stimulating local production in rural areas would benefit farmers growing feedstocks and create jobs in industries along the value chain (Arndt et al., Citation2012; Schuenemann et al., Citation2016).

This paper reviews the domestic political and legislative context that surrounds biofuels initiatives to highlight what opportunities exist for establishing a biofuels trade network between South Africa (as an anchor market) and its neighbours, specifically in Zambia and Mozambique. As discussed in other papers in this series (Sallie et al. this issue), there are likely strong benefits from pursuing a regional market approach, since South Africa has the largest fuel market but is relatively constrained in its potential to expand feedstock production compared to its neighbours, which are better endowed with the natural resources to pursue expanded feedstock production (von Maltitz et al. this issue). To explore this topic, this paper look at the experiences to date in trying to stimulate biofuel blending, and some of the underlying reasons why these efforts have stalled.

2. Methodology

We review recent literature to identify the relevant commitments countries have made to both international agreements and in their domestic policies, and discusses how these impact the future of the biofuels sector. The products of interest include liquid biofuels ethanol and biodiesel, and their typical feedstocks.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. We start by reviewing recent global trends in biofuels that exert a significant influence on the potential for domestic development of biofuels in Southern Africa. We then focus on the biofuels and broader trade policy framework in South Africa, and whether this allows it to act as an anchor market for imports in the region. We then look at the role of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and its regional energy agenda might facilitate trade in biofuels. Finally, we discuss the policy framework and status of biofuels production in Mozambique and Zambia to understand scope for producing for a regional market.

3. Biofuels and policy in Southern African countries

Biofuels are a complementary and alternative energy source to fossil fuels and have the potential to generate energy from various biomass sources including sugar, starch and oil crops and forestry materials. Global biofuels demand has been largely spurred by the transport sector and more especially by road vehicles, which use biofuels either in pure form or blended into conventional fossil fuels. Enthusiasm for biofuels production in recent decades led to the launch of new national and legislative and regulatory frameworks that sought to expand output and consumption of biofuels, including the countries discussed in this paper. Since biofuels are more expensive to produce and consume than fossil fuels, stimulating the development of the market requires government intervention, such as subsidies and mandatory use of biofuels.

Several southern African countries have developed part of the policy framework to incentivise biofuels demand, including mandates that require distributors to add fuel ethanol to gasoline (). In the case of Malawi, an ethanol blending mandate has existed since 1982, whereas in most other countries they have been introduced more recently.

Table 1. The state of biofuel mandates in selected Southern African countries.

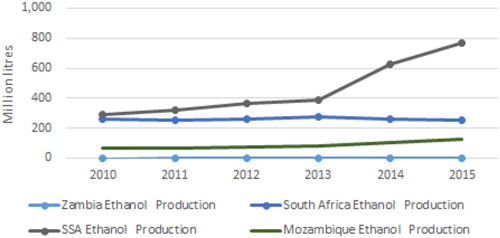

However, the legislative developments to date have been insufficient to spur the growth of production and consumption, as projected would happen a decade ago. Production in Southern African countries of interest (South Africa, Zambia, and Mozambique) has remained marginal (see ).

Figure 1. Ethanol production and consumption in Southern Africa (2010–15) (million litres). Source: Authors’ compilation using data from OECD/FAO (Citation2016).

Reasons for this include adverse developments in global energy and commodity markets and in domestic markets, competition with incumbent fuel distribution and negative experiences of attempting to implement land-intensive feedstocks. Each is discussed further below.

4. Overview of global biofuels and feedstock policy and market development

Conditions in global energy markets in general and policies towards renewable energy and biofuels in particular, influence prospects for development of biofuels in Southern Africa. While trends in oil prices determine the overall economic rationale for replacing fossil fuels with biofuels in all countries (producers and consumers), much of both the public and private interest and investment into developing biofuels in Southern Africa in the late 2000s was driven by expectations that it would be possible and profitable to export biofuels to the EU, which offered large markets and favourable access for selected countries (Charles et al., Citation2009).

4.1. Trends in global biofuel policy and markets

Over the last 15 years, biofuels production has expanded rapidly globally, with most growth concentrated in the three largest markets (the United States (US), EU, and Brazil) and in the period up to 2011, after which growth slowed but international trade increased (Beckman, Citation2015).

The early 2000s saw major economies introduce policies and legislation that would expand demand for biofuel production and consumption. In Europe, the Fuel Quality Standard and the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED) called for an increase in biofuel use from 15 billion litres in 2009 to around 45 billion litres in 2020. The RED required that 10 per cent of Member States’ total transport fuel should come from biofuels.

In the US, the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act and Renewable Fuel Standard set out a pathway to ramp up consumption of biofuels to 36 billion gallons by 2022 (tripling the 2009 level of consumption of 11 billion gallons), with sub-targets for different categories of fuel. Mostt of the increase was to come from advanced (21 billion gallons) and cellulosic (16 billion gallons) biofuels.

4.1.1. EU

Meeting EU mandates required imports to complement production from the Member States. While the expectation in the early 2000s was that the major exporters – Brazil, the US, and Argentina – would be the main suppliers to the EU, rulings in 2011 to impose anti-dumping and countervailing duties on imports from these countries opened up the prospect of importing biofuels from sub-Saharan African countries, which alongside other developing established producersFootnote1 enjoyed preferential treatment (Beckman, Citation2015).

However, growing concern over the sustainability of biofuels produced outside the EU led to further reforms that raised barriers to access for EU markets. Responding to concerns regarding the impact of biofuels production on land use change and food security, in 2015 the European Parliament passed legislation introducing a cap at 7 percent of the volume of transport fuels that could come from food or feed crops in 2020. Together with a requirement that all biofuels be certified by one of around 20 voluntary schemes, this limited the opportunity for producers in third countries to export biofuels to the EU at competitive prices (Pacini & Assunçao, Citation2011).

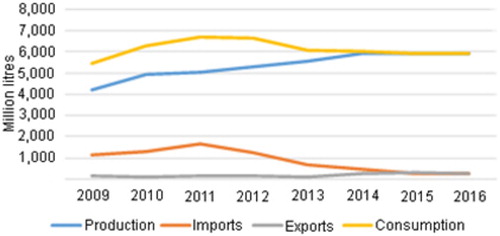

At the same time, lower prices for agricultural commodities that contribute to biofuel feedstocks made it profitable for EU producers to increase production of biofuels. Together, these factors led to closing the gap between EU supply and demand (see ). While the EU imported over 1.5 billion litres of bioethanol in 2011, this had reduced to under 500 million litres in 2015 (ePURE, Citation2016). In 2015, the EU was 99 per cent self-sufficient in bioethanol and 97 per cent self-sufficient in biodiesel (USDA, Citation2015).

Figure 2. Supply and demand for bioethanol in the EU (2006–16; million litres). Source: Authors’ compilation based on data in USDA (Citation2015).

Under present conditions, it is unlikely that the EU will hit the 7 percent cap for food-based biofuels before 2020 (USDA, Citation2015). At the moment, it is also unclear what policy prescriptions the EU will mandate beyond 2020. An official EU Communication in 2014 suggests the European Commission will not establish new targets for renewable energy or the greenhouse gas intensity of fuels used in the transport sector or any other subsector after 2020 and that biofuels from food-based feedstocks will not receive public support after 2020 (European Commission, Citation2014).

4.1.2. USA

Production of US ethanol has grown year-on-year, and the US is the world’s top producer, accounting for 49 percent of all production (OECD/FAO, Citation2016). However, having already reached the maximum mandated levels for ethanol consumption, domestic consumption is not expected to grow substantially, although trade is expected to increase moderately. Major factors driving the expansion of trade are the saturation of the US ethanol market and the US specification for advanced biofuels under renewable mandates (OECD/FAO, Citation2016).

US ethanol market saturation was the result of production ‘hitting the blending wall’; due to engine specifications and manufacturers’ terms, the total volume of ethanol blended with all US gasoline remains limited to 10 per cent of fuel sales.

US consumption of renewable transport fuel is not expected to meet the legislated targets of 36 billion gallons by 2022. This shortfall is due to the lack of progress in meeting targets for advanced biofuels, including cellulosic biofuels. In 2015, US production of liquid cellulosic fuel amounted to 2.6 million ethanol-equivalent gallons, which corresponds to less than 0.1 percent of the legislated target for that year. Very low volumes of advanced biofuels are expected to come on-stream by 2025, and it is expected that the US will miss the target set in the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) (OECD/FAO, Citation2016). This downgrading of demand for advanced biofuels explains part of the steady decline of US bioethanol imports. In 2016, the US imported 34 million gallons of fuel ethanol – the lowest volume since 2010, and much of the shortfall is driven by historically low Brazilian exports (RFA, Citation2017).

The combination of cheap and plentiful feedstock of US corn coupled with a fixed domestic demand imposed by the blend wall and cheap gasoline has turned the US into a major exporter of ethanol. Exports for 2016 – a year characterised by a bumper corn harvest and cheap oil – are expected to be 885.3 million gallons, the highest level in six years (Cooper, Citation2016). Major destination markets include some countries that have policy-induced demand for ethanol, which they are unable to meet through domestic production (ITA, Citation2016).

The above discussion suggests that for the foreseeable future, biofuel producers in Southern Africa are unlikely to face favourable export opportunities to the US and European countries that account for most consumption. Also, as policy changes mean these traditional importers import less, established producers may look to new markets and sell in these at a lower cost than domestic producers (Koehler, Citation2016). Domestic or regional trade measures would therefore be necessary to protect an infant Southern African industry and make it competitive (discussed below).

4.2. Overseas development support: current and prospects for export markets – waning interest (and support) from the EU

As discussed above, changes in both the domestic policies of countries that dictate global biofuel expansion and in oil and commodity markets have dampened enthusiasm for biofuel production in Southern Africa. Changes to European legislation have effectively closed out opportunities to import biofuels from third countries, disincentivising investors from pursuing biofuels projects abroad.

In the early 2000s, the European Commission was keen to promote biofuels for mutual benefit, as demonstrated by their early inclusion in the 2008 EU–Africa Energy Partnerships, which foresaw economic cooperation to develop Africa’s energy infrastructure and help the EU meet its renewable energy targets (Charles et al., Citation2009). However, the ongoing challenges in getting biofuels projects ‘off the ground’, coupled with the accusations of land grabbing, effectively limited support for biofuels development from EU regional mechanisms and the Member States. The primary funding mechanism for EU support to the renewable energy sector – the Africa–EU Renewable Energy Cooperation Programme (RCEP) – explicitly excludes support to biofuels projects in its eligibility criteria (RCEP, Citationn.d.). Similarly, the US-led funding instrument for innovation in renewable energy in Africa – Powering Agriculture: Energy Grand Challenge – does not include among its awardees projects pursuing first-generation biofuel projects (Powering Agriculture, Citationn.d.).

4.3. Trends in sugar and oil markets

While it is difficult to project developments in the oil and agricultural commodity markets that underpin demand and supply of biofuels, current policies are likely to have an impact. While the EU’s duty-free, quota-free access to Southern African countries (excluding South Africa) has provided a growing opportunity for exports and income for exporters, these are projected to decline as the EU sugar regime reforms and these countries lose access. A 2016 report by the European Commission suggests that sugar exports from African, Caribbean, and the Pacific Group of States (ACP) to the EU fell by 22 per cent between 2013 and 2015. This resulted in part from the cutting of the reference price by 36 per cent from US$524/tonne to US$335/tonne. This is in line with an earlier report (European Commission, Citation2013) suggesting that European imports from ACP countries would half by 2023.

As domestic consumption of sugar is expected to rise faster than population growth in sub-Saharan countries, national and regional markets are expected to pick up some of this slack (OECD/FAO, Citation2016). In several countries, governments have raised domestic reference prices, lowered taxes and raised trade barriers in order to insulate the domestic sugar industry (Dubb et al., Citation2016). However, the trends in global sugar markets discussed above add an imperative to diversify sugarcane production into ethanol production (Kohler, Citation2016).

5. Issues surrounding demand of biofuels in South Africa

5.1. South Africa’s policy on biofuels

In 2007 the South African government committed to a short-term goal in the production of biofuels, amounting to 2 percent of the total road transport pool. To date, large-scale procurement has not yet commenced. According to the Biofuels Industrial Strategy, mandatory blending was expected to commence in October 2015. However, this has not materialised and owing to the potential cost to the fiscus of the existing support mechanism during the ongoing period of low oil prices, in 2015 the government revised the processing of allocating the subsidy to one which is based upon companies submitting competitive bids, rather receiving a sum based upon a commodity price index (Roelf, Citation2015). The low oil prices, together with concerns around food security and the policy framework have led to the government temporarily halting the policy development process around biofuels (Canegrowers Association, Citation2016). While the biofuels policy supports both biodiesel and bioethanol blending, bioethanol has attracted more attention due to country’s large sugarcane sector that could contribute to ethanol production, alongside the large petroleum liquid fuel market. In contrast, biodiesel production is at a much earlier stage with no large scale manufacturing have emerged.

5.1.1. Relevant political economy issues explaining lack of progress on biofuels promotion and regulation

Different rationales underpin expanding the consumption and production of biofuels in South Africa. On the consumption side, South Africa’s dependence on imported oil, which accounts for 65% of its transport energy demand and is South Africa’s single most significant import is perceived to be both expensive and potentially destabilising for the economy during price spikes (Kohler, Citation2016). The potential to cut spending on imports is therefore a major argument favouring the expansion of domestically-sourced biofuels. As argued in other papers in this special edition it is economically more attractive to purchase biofuels sourced from neighbouring countries which house stronger economic ties with the South African economy than from oil producers where trading relationships are typically thin.

However, the mechanism proposed in South Africa’s biofuel legislation to subsidise biofuel production through a levy on fossil fuels has proved to be challenging to introduce amid concerns of other tax rises and inflation (Roelf, Citation2015). While potentially environmental benefits of biofuel expansion are commonly emphasised in other countries, environmental criteria do not feature strongly in either South African regulations or public discourse on the benefits of biofuels. Kohler (Citation2016) calculates that the volumes mandated by the Biofuels Industrial Strategy would result in less than a 0.15% reduction in South Africa’s emissions, and that bigger savings could be made elsewhere in the transport energy sector, such as eliminating consumption of synthetic fuels.

In comparison with the relatively straightforward rationale on the consumption side, the production side in South Africa is characterised by competing objectives and interests, which are closely linked to broader goals and narratives that define policy choices in the rural sector.

Regarding generating benefits, one of the main objectives of the Biofuels Industrial Strategy is job creation and reducing poverty in former homelands (Brent, Citation2014). This is consistent with the aims of the emphasis in the National Development Plan which aims to create one million jobs in agriculture by 2030. This preference for smallholder cultivation is reflected both in the wording of the BIS, the prioritisation of under-used land and in the choice of permissible feedstocks, which include crops grown by smallholders such as sorghum.

At the same time, an imperative for biofuels development is to avoid imperilling food security, and to minimise the risk of this, the biofuels strategy excludes maize from the list of eligible bioethanol feedstocks, instead promoting sugar beet and sugarcane.

As discussed above, trends in global sugar markets create incentives for South African sugar producers to diversify into other markets, and the development of a sugarcane-based bioethanol industry would meet this need. However, Kohler (Citation2016) finds that the current level of proposed support for biofuel producers is not sufficiently attractive to stimulate production as the proposed subsidy would cover the costs of (sugarcane)feedstock but not operating or capital costs. Stimulating domestic supply appears to necessitate waiving taxes and levies, and delinking cushioning subsidy payments from international oil prices and the exchange rate. However, it is unclear this would be politically acceptable, given preferential treatment already received by South Africa’s sugar sector which exceeds that of other sectors.

The discussion above suggests that South Africa is unlikely to meet its own biofuels mandate under the current biofuels policy and pricing framework: the government will not offer the price incentives and assurances to for sugarcane investors to make investments in production.

This therefore raises the question of whether (i) South Africa would import biofuels from neighbouring countries; (ii) if neighbouring countries could produce biofuels for export to South Africa. The next section looks at opportunities and challenges provided by South Africa’s domestic legislation and regional initiatives.

5.2 . Trade opportunities

South Africa has broader ambitions to pursue regional integration with its neighbours. South Africa’s regional integration approach involves market integration, regional infrastructure development support, and coordination with the aim of boosting intraregional trade and diversifying production. In 2016, South Africa made Africa its priority trading partner and aims to double its exports to Africa (Department of Trade and Industry, Citation2016).

On the regional front at the SADC level, the SADC Trade Protocol applies as all countries under review are members to it. In terms of trade, since the SADC region is now a free trade area (FTA), substantially all goods originating from member states should enter each other’s jurisdiction duty-free, and therefore duty-free access applies to fuel or feedstocks from the region and more specifically into Mozambique, South Africa, and Zambia, which have substantially liberalised their markets. Use of feedstock from third-party countries would be restricted by the strict rules-of-origin requirements that confer origin, and in this case, should be wholly obtained from the region (SADC, Citation2003).

It is therefore anticipated that under the current trade regime, there would be no trade restrictions and biofuels and feedstock should not attract tariffs. A search for the current tariff schedules as reported by the United Nations ITC MacMap database (www.macmap.org) indicates that all goods (i.e. bioethanol and feedstocks) enter duty-free in the respective markets. Currently, tariffs for ethanol applied on a non-preferential basis are low at below 10 per cent for all countries under review.

However, South Africa’s domestic biofuels policy appears to rule out opportunities to import large quantities of biofuels as biofuels manufacturers can only be licensed if they demonstrate they will source from domestic (preferably emergent) farmers (Henley, Citation2014). Exceptions are made only when feedstocks either at the start of a project or – at a later stage – during a period of adverse agricultural production which prevents investors from sourcing feedstocks from farmers (Department of Energy, Citation2015). The regulations also require manufacturers importing feedstocks to determine the carbon footprint of imports and provide a plan for how imports will be replaced by domestic production.

It is unclear if the restrictions on the local sourcing requirements are permissible under its membership of SADC and the WTO. Harmer (Citation2009) highlights issues for consideration by policymakers when dealing with biofuel subsidies and WTO rules; the main issues being the WTO’s Agreement on Agriculture states that subsidies should not come from consumers and provide price support to producers. For South Africa, the issue of subsidies needs further interrogation as there is a provision in South Africa’s biofuel policy that allows for subsidies, which are consumer-funded through a general fuel levy (Biofuels-News, Citation2015).

To stimulate a Southern African market, it would likely be necessary to establish preferences for intra-regional trade, while restricting imports from outside the region. Low-cost producers of ethanol from non-SADC countries such as Brazil presents a challenge for the region, given that most SADC members are bound by WTO rules that have left them with limited policy space to increase tariffs on ethanol to reduce imports.

5.3. Regional coordination: challenges for regional cooperation on biofuels

While SADC had a biofuels task force that was operational between 2008 and upto at least 2012, this focused more on supporting development of domestic biofuel policies (BEFS, Citation2012) and has been inactive in recent years. Although SADC could be a vehicle through which to promote biofuels trade as part of its regional energy portfolio, doing so currently faces a number of challenges. Transport fuels are not high up the list of current SADC priorities (Cilliers, Citation2012). According to the SADC’s Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP), the following are sectoral cooperation and integration intervention areas:

trade/economic liberalisation and development;

infrastructure support for regional integration and poverty eradication;

sustainable food security; and

human and social development.

Energy is mentioned under infrastructure support, but this is targeted mainly at electricity generation and supply (SADC, Citation2007). Overall commitment has wavered to the renewable energy projects identified in the Regional Infrastructure Development Master Plan, as members have prioritised power-sharing. While SADC’s Protocol on Energy and the RISDP address the SADC’s broad energy objectives, they make little mention of renewable energy aside from hydropower, and there is no region-wide regulatory framework that specifically addresses renewable energy.

A regional renewable fuel policy could call for member states to promote and support the production and consumption of SADC ethanol, similar to Annex VII to the Protocol on Trade, which seeks to support SADC sugar production. Part of the objectives of the Annex is ‘to provide temporary measures to insulate Member States’ sugar producing industries from the destabilising effects of the distorted global market, and in this regard to harmonise sugar policies and regulate its trade within the region during the interim period until world trade conditions permit freer trade in sugar’ (SADC, Citation1996:92).

6. Scope for production in neighbouring countries

This section discusses the policy and regulatory environment, as well as some of the main policy priorities in the energy, rural, and agricultural sectors. The aim here is to provide a picture that will help to clarify the key issues facing potential domestic production in Mozambique and Zambia, and stimulate consumption and imports in South Africa. This section discusses for each country (1) the main policies and legislation in the energy and rural sectors that have a bearing on biofuels; (2) the political economy issues that help to explain a lack of progress in completing biofuels regulation or hinder implementation.

6.1. Zambia

Like elsewhere in Southern Africa, the early 2000s saw major investments in biofuels. Commercial biofuels production in Zambia started in the beginning of the 2000s with six major firms engaging in production (D1 Oils, ETC Bioenergy, Marli Investments, Oval Biofuels, Kansanshi Mines, and Southern Biopower) (Chu, Citation2013). The emphasis of this early investment was Jatropha, and companies experimented with different production models, planting both large areas and working through outgrowers (German et al., Citation2011).

This interest in commercial production spurred the creation of policy, institutional, and legislative frameworks. In 2008, the Zambian government issued the National Energy Policy and created national standards for biofuels. Blending ratios followed in 2011 (5 percent for biodiesel and 10 percent for bioethanol), as shown in .

Table 2. Key dates in the development of Zambia’s biofuels industry.

However, these steps did not lead to the expansion of the industry and several of the earlier investors exited the sector. Important reasons for this include the global financial crisis that constrained access to capital and the failure to reach projected levels of supply due to crops underperforming compared to expectations, and difficulty obtaining land. On the institutional and policy front, the industry expanded before legislation was in place, and before 2014 there were no supply agreements in place between the government and the private sector. This meant that firms could not make production/investment decisions as there was no guaranteed market for biofuels locally, except for separate arrangements with individuals or firms. In addition, this also meant that firms could not secure finance from financial institutions using the supply agreements as security (Samboko & Henley, Citationforthcoming). The failure of eearly experieces was also a direct consequence of government subsidies on fuel imports (Locke & Henley, Citation2013), with subsidies rendering biofuels uncompetitive against fossil fuels. Interest in biofuels investment has picked up on a smaller scale in the last two years, with investments announced for a Chinese-backed US$150 million cassava-based ethanol plant in Luapula, and ongoing efforts by a mining company to produce biodiesel.

6.2. Mozambique

In Mozambique, biofuels became the subject of sustained policy attention in the early 2000s when the government attempted to establish small-scale Jatropha plantations in every district in order to diminish reliance on oil imports (Schut et al., Citation2010). The 2007 Rural Development Strategy included as an objective the development of alternatives to traditional fuels, including from sugarcane, sweet sorghum, Jatropha, and other crops. The same year saw the approval of the first biofuels project. Government backing for the biofuels sector increased in subsequent years with the launch of the National Policy and Strategy for Biofuels, adopted in 2009. The policy pursues several objectives, which include:

‘promoting sustainable production of biofuels;

reducing the country’s dependence on imported fossil fuels;

diversifying the sources of energy; promoting sustainable rural development;

contributing to foreign exchange generation through increased exports;

exploring regional and international markets;

promoting research on technologies for production of biofuels by national teaching and research institutions including technologies applicable to local communities;

promoting food and nutritional security;

reducing the cost of fuel for the final consumer; and

protecting the national consumers against the volatile prices of fossil fuels and energy insecurity’ (Nhantumbo & Salomão, Citation2010).

The policy also sets out a list of conditions to prevent the planting of biofuel feedstocks on sensitive areas, and to limit their impact on biodiversity. However, these provisions did not receive adequate attention from either investors or government agencies monitoring the evolution of the sector, and the list of concerns surrounding the potential rapid pace of expansion in the absence of effective planning resulted in the government announcing a moratorium from 2009 to 2011 until national land use planning had been carried out (Schut et al., Citation2010). To improve planning of biofuel developments, in 2014 the government of Mozambique was in the process of approving the biofuels sustainability criteria framework document, which specifically mentions that investments should not negatively impact local food security. Operators must provide evidence that they are following a plan to maintain access to basic food crops in the region compared to the situation before operations. No mandatory percentage of land allocated for food production is mentioned in the strategy or sustainability criteria (Schut and Florin, Citation2015).

The policy also calls for operators to create employment and broader conditions for local economic development through purchasing feedstock from neighbouring farms (Schut and Florin, Citation2015).

Despite the well-developed policy and regulatory framework for biofuels in Mozambique, production and consumption in the fuel sector have yet to take off, with the only commercial success so far being the production of ethanol gel. While the lack of economic viability of Jatropha explains much of the failure of biodiesel production, the industry has encountered a broader set of challenges (Msangi & Evans, Citation2013). Getting access to finance in the wake of the 2011 financial crisis became difficult for all operators, especially since a large number of producers in Mozambique included in their strategies plans to export to the EU; when this option was closed, the plans became unviable. Operators complained that gaining access to land use rights that provided investors with security to invest further was a major hindrance (Atanassov, Citation2013).

7. Discussion and Conclusions

While previously, global market trends and policies in importing countries suggested a window existed for biofuels projects in developing countries to both attract finance for project development and to find export markets overseas, more recent changes in developed country biofuel policies and global market conditions have reversed these opportunities. In addition, experience to date suggests that translating this potential into reality requires overcoming numerous challenges, some of which have limited development of the agricultural sector for decades. These include poorly developed infrastructure, complications associated with land tenure, conflict, and poor governance, and – for smallholders – lack of access to inputs, output markets, and agricultural extension. Other critical factors include competing demands for land use that may threaten food security and the availability of water resources. summarises the positive and negative influences that contribute to prospects of expanding biofuels.

Table 3. Factors with positive and negative influences on biofuel expansion.

While proponents of biofuels continue to argue that there is scope for biofuels development in the SADC to develop rural areas, increase rural incomes, and enhance both food and energy security, biofuels projects have largely failed to develop. At the domestic level, there are currently unclear signals of commitment from government to enforce biofuel mandates through either purchasing offtake agreements or requiring refineries to blend biofuels with imported fuels. This suggests biofuel promotion continues to be a low priority among key decision makers in government. Similarly, this lack of prioritisation is reflected at the SADC level, where interest has been focused on electricity integration and interest in developing a regional biofuels sector has been limited. Reviving interest in biofuels at this level would likely require firmer interest from national governments.

For investors, previously high levels of interest in biofuels appear to have waned in a climate of narrower access to overseas markets, more stringent requirements to access credit, and low prices for oil and sugar, which equate to thinner margins. While the anticipated fall in sugar prices resulting from reforms to EU sugar markets suggests diversification into ethanol is likely to be an attractive option, the fact that sugar prices continue to stay above ethanol prices has meant that interest has been subdued. Awareness of social risks associated with biofuels production – both in terms of the precariousness of returns and those posed to surrounding communities – has limited the appetite for public and private investors to back biofuels projects without a higher level of due diligence. For development partners, interest in supporting biofuels projects has waned and there appears to be less funding available for projects.

Nevertheless, analysis of trade-related dimensions suggests that if the idea of a regional market gains purchase among domestic governments, companies, and investors, trade between countries could be achieved. The major obstacle would be to clarify the biofuels regulations in South Africa to allow blenders to continue to benefit from subsidies even if imports from neighbouring countries enter into the fuel mix, while offering some measure of protection from cheaper imports elsewhere.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The EU trade agreements with Guatemala, Pakistan, and Peru included provisions to import ethanol (Beckman Citation2015).

References

- Arndt, C, Pauw, K & Thurlow, J, 2012. Biofuels and economic development: A computable general equilibrium analysis for Tanzania. Energy Economics 34, 1922–30.

- Atanassov, B, 2013. The status of biofuels projects in Mozambique. Background report for scoping report on biofuels projects in five developing countries. Overseas Development Institute, London.

- Beckman, J, 2015. Biofuel use in international markets: The importance of trade. Economic Information Bulletin Economic Research Service, Washington, DC.

- BEFS (Bioenergy and Food Security Project), 2012. Forum summary: SADC capacity development forum. Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Biofuels-News, 2015. Low oil prices force South Africa to remodel biofuels policy. http://biofuels-news.com/display_news/9512/low_oil_prices_force_south_africa_to_remodel_ biofuels policy Accessed December 2016.

- Brent, A, 2014. The agricultural sector as a biofuels producer in South Africa. Understanding the food energy water Nexus. WWF-SA, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Canegrower’s Association, 2016. Review of the board of directors 2015/2016. South Africa Canegrowers Assocation, Mount Edgecombe, South Africa.

- Charles, MB, Ryan, R, Oloruntoba, R, von der Heidt, T & Ryan, N, 2009. The EU–Africa energy partnership: Towards a mutually beneficial renewable transport energy alliance? Energy Policy 37(12), 5546–56. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.08.016

- Chu, J, 2013. Creating a Zambian breadbasket. ‘Landgrabs’ and Foreign investment in agriculture in Mkushi District, Zambia. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, UK.

- Cilliers, B, 2012. An Industry Analysis of the South African Biofuels industry. Mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Business Administration, North-West University. http://dspace.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/9002/Cilliers_BL.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed December 2016.

- Cooper, G, 2016. Ethanol and DDGs export jump in July. Ethanol RFA website. http://ethanolrfa.org/2016/09/ethanol-and-ddgs-exports-jump-in-july/ Accessed December 2016.

- De Keyser, S & Hongo, H, 2005. Farming for energy for better livelihoods in Southern Africa – FELISA. Paper presented at the Role of Renewable Energy for Poverty Alleviation and Sustainable Development in Africa, 22 June, Dar-es-Salaam.

- Department of Energy, 2015. State of renewable energy in South Africa. . Department of Energy, Westlake, South Africa. www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/State%20of%20 Renewable%20Energy%20in%20South%20Africa_s.pdf (accessed December 2016).

- Department of Trade and Industry, 2016. Trade, exports & investment. www.dti.gov.za/trade_investment/trade_investment_Africa.jsp Accessed December 2016.

- Dubb, A, Scoones, I & Woodhouse, P, 2016. The political economy of sugar in Southern Africa: Introduction. Journal of Southern African Studies. doi:10.1080/03057070.2016.1214020.

- ePURE, 2016. Statistics on imports of Ethanol into the EU. http://epure.org/media/1475/imports-duties.png

- European Commission, 2013. Prospects for agricultural markets and income in the EU 2013–2023. European Commission, Brussels.

- European Commission, 2014. A policy framework for climate and energy in the period from 2020 to 2030. European Commission, Brussels.

- German, L, Schoneveld, G & Gumbo, D, 2011. The local social and environmental impacts of smallholder-based biofuel investments in Zambia. Ecology and Society 16(4), 12.

- Harmer, T, 2009. Biofuels subsidies and the law of the World Trade organization. Issue Paper 20, ICTSD Programme on Agricultural Trade and Sustainable Development. International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, Geneva.

- Henley, G, 2014. Markets for biofuel producers in Southern Africa: Do recent changes to legislation in the region and EU bring new opportunities? EPS-Peaks Report. Overseas Development Institute, London.

- International Trade Administration, 2016. 2016 top markets report: Renewable fuels sector snapshot. http://trade.gov/topmarkets/pdf/Renewable_Fuels_Fuel_Ethanol.pdf Accessed December 2016.

- Kohler, M, 2016. An economic assessment of bioethanol production from sugar cane: the Case of South Africa. Economic Research Southern Africa Working Paper 630.

- Locke, A & Henley, G, 2013. Scoping report on biofuels projects in five developing countries. Overseas Development Institute, London. www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8394.pdf Accessed February 2016.

- Msangi, S & Evans, M, 2013. Biofuels and developing economies. Is the timing right? Agricultural Economics 44(4–5), 501–10. doi: 10.1111/agec.12033

- Nhantumbo, I & Salomão, A, 2010. Biofuels, land access and rural livelihoods in Mozambique. International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

- OECD/FAO (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/Food and Agriculture Organisation), 2016. OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2015. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Pacini, H & Assunçao, L, 2011. Sustainable biofuels in the EU: the costs of certification and impacts on new producers. Biofuels 2(6), 595–98. doi: 10.4155/bfs.11.138

- Powering Agriculture, n.d. About powering agriculture. https://poweringag.org/about Accessed December 2016.

- RCEP, n.d. Eligibility. www.africa-eu-renewables.org/finance-catalyst/recp-finance-catalyst-solution Accessed December 2016.

- RFA (Renewable Fuels Association), 2017. 2016 U.S. Ethanol exports and imports. Statistical summary. http://ethanolrfa.org Accessed January 2017.

- Roelf, W, 2015. Cheaper oil forces South Africa to rework biofuels subsidy. Reuters. http://af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFKCN0QG0RJ20150811 Accessed December 2016.

- SADC, 1996. Protocol on trade annex VII: Concerning trade in sugar. www.tralac.org/files/2011/11/SADC-Trade-protocol-Annex-VII.pdf Accessed December 2016

- SADC, 2003. Rules of origin exporters guide manual. Southern Africa Development Community, Gaborone.

- SADC, 2007. Regional indicative strategic development plan (RISDP). Southern Africa Development Community, Gaborone.

- Samboko, K & Henley, G, forthcoming. Constraints to biofuel feedstock production expansion in Zambia. Development Southern Africa.

- Schuenemann, F, Thurlow, J & Zeller, M, 2016. Leveling the field for biofuels: Comparing the economic and environmental impacts of biofuel and other export crops in Malawi. IFPRI Discussion Paper 01500. IFPRI, Washington, DC.

- Schut, M, & Florin, MJ, 2015. The policy and practice of sustainable biofuels: Between global frameworks and local heterogeneity. The case of food security in Mozambique. Biomass and Bioenergy 72, 123–35.

- Schut, M, Slingerland, M & Locke, A, 2010. Biofuel developments in Mozambique: Update and analysis of policy, potential and reality. Energy Policy 38(9), 5151–65. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2010.04.048

- Searle, S & Malins, C, 2015. A reassessment of global bioenergy potential in 2050. GCB Bioenergy 7(2), 328–36. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12141

- Souza, GM, Victoria, RL, Joly, CA & Verdade, LM, 2015. Bioenergy & sustainability: bridging the gaps, scientific committee on problems of the environment (SCOPE). Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment, Paris, France.

- UNCTAD, 2009. South-South and triangular cooperation in the biofuels sector: the African experience. Paper prepared by the UNCTAD Secretariat for the Multi-year Expert Meeting on International Cooperation and Regional Integration, 14–16 December, Geneva.

- United States Department of Agriculture, 2015. EU-28 biofuels annual 2015. GAIN Report NL5028. USDA Foreign Agriculture Service, Washington, DC.