?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study tests whether the performance of South Africa’s trade balance, that is, the country’s export and import performance, can effectively explain the economy’s growth rate. Formally, the study tests the applicability of Thirlwall’s law to the South African economy. The law states that the estimated growth rate of an economy is proportional to the growth rate of exports

divided by the income elasticity of imports

. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) quarterly data from 1960 to 2009 for exports, imports, the exchange rate, export prices, import prices, and the economic growth rate is used for regression. The study runs an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model in the presence of structural breaks and after adjusting for structural breaks and finds that growth in the South African economy can be shown to be trade balance constrained. This finding has policy implications with regard to trade promotion and strategies and strategies to enhance growth performance by increasing the overall competitiveness of the South African economy.

1. Introduction

Over the years, there has been a great amount of literature from different schools of economic thought on the topic of how best to promote sustained economic growth. The schools of thought differ about what factors stimulate and constrain growth and why growth rates differ across countries and over time.

Previously, many economists looked at economic growth primarily as a supply-side phenomenon. It was argued that economic growth could be explained by the growth rate of supply factors, to which demand would inevitably adapt (Solow, Citation1956). Moreover, the supply-side model can be augmented to include variables such as human capital, education, health, and research and development to better explain differences in growth rates across countries. (Mankiw, Citation1992). These variables are postulated as accelerators rather than direct determinants of economic growth.

In an open macroeconomic context, a popular Keynesian demand-oriented approach emphasising the external constraints to growth is the so-called theory of ‘balance-of-payments-constrained growth’ (Lima, Citation2007). This was formalised in what came to be widely known as Thirlwall's law, named after the work presented by Anthony Thirlwall in his seminal 1979 paper titled ‘The balance of payments constraint as an explanation of the international growth rate differences’ (Thirlwall, Citation1979). Thirlwall’s law states that the estimated growth rate of an economy is proportional to the growth rate of exports

divided by the income elasticity of imports

. In his paper, Thirlwall argued that growth rates differ because the growth of demand, particularly open-economy-related demand, differs between countries.

Thirlwall's insight harkened after Keynes in that it directed the government to grow the economy by stimulating aggregate demand. More particularly, Thirlwall expounded the idea that the economy should be export-oriented as exports constitute, at least potentially, a significant component of aggregate demand (Palley, Citation2012). Put succinctly, the balance-of-payments-constrained growth model suggests that the growth rate of the economy can be explained by the growth of external balance, particularly the growth of a trade balance.

Since Thirlwall’s first publication in 1979, there have been a number of studies seeking to test Thirlwall’s law with some arguing strongly that the law is theoretically and empirically robust (Setterfield, Citation2011). Economists began to test the validity of the law across different countries and different continents such as in Latin American (Cruz, Citation2000) Asian and Africa (Hussain, Citation1999) and member countries of Organisations for Economic Corporation and Development (OECD) (Hein, Citation2008). A recent study was undertaken on the validity of Thirlwall's law to the Egyptian economy (Elish, Citation2018).

This article contributes to the literature by assessing the applicability of Thirlwall’s law as an explanation of various periods of growth in the South African economy. The second section provides a brief literature review on the theory of demand-led growth. This section discusses the Keynesian demand-determined growth model, studies testing Thirlwall's law and provides an empirical review on the balance of payments crisis in South Africa and its impact on growth. The third section provides a formal presentation of Thirlwall's law. The fourth section tests the applicability of Thirlwall’s law to various periods of economic growth in South Africa and results are discussed. The last section concludes with a brief discussion on the broad policy implications of the article’s findings for the South African economy.

2. Literature review

2.1. Keynesian: Demand-determined growth model

Keynesian economists make the argument that aggregate demand plays an important role in economic growth. In equilibrium, the growth rate of output must equal the growth rate of aggregate demand, which implies that aggregate demand is a potential constraint to growth (Pilley, Citation1996). Effectively, within limits, the growth rate of output can be increased by increasing aggregate demand (Dutt, Citation2006).

Additionally, capital accumulation is driven by investment such that it is investment spending that determines the rate of capital accumulation (Pilley, Citation1996). However, unlike in the neoclassical framework, investment varies independently of savings in the Keynesian model (Setterfield, Citation2003).

Initially, the Keynesian growth theory was widely regarded as a closed macroeconomic model until Thirlwall’s law was presented in 1979, which forcefully argued that demand-led growth could best be explained through an open economy lens, thus opening the way for balance-of-payments-constrained economic growth theory (Lima R. a., Citation2007).

The idea of a closed economy presumed that economic growth difficulties might be attributed to governments’ inability to expand demand. However, this argument was theoretically not satisfactory and (Thirlwall A., Citation1979) argued that, for any open economy, the dominant constraint to growth is a set of factors embedded in that economy’s balance of payments.

2.2. Studies testing Thirlwall’s law

Mostly, economists have been investigating whether the law holds in different economies (developed and developing) and across multi-economic sectors. For instance, (Lima, Citation2010) demonstrated for Latin American countries that structural changes in the sectoral composition of exports and imports affect the extent of the external constraint. Thus, it is only exports that bestow an ability to increase an economy’s expenditure without generating external disequilibrium (León-Ledesma, Citation1999). Studies such as those done by (Porcile, Citation2002) used the law to test the effectiveness of export-led growth in Brazil from 1890 to 1973.

Even though Thirlwall's law was tested generally across countries with the flexible exchange rate, there is no statistically significant role that has been found to be played by the terms of trade in long-run growth (Cruz, Citation2000) However, it remains of research interest to study the implications of exchange rate policies on long-run growth. A country can devalue its nominal currency in an attempt to improve the balance of payments equilibrium growth rate, provided that in real terms the exchange rate devaluation is not eroded by domestic inflation; and that the sum of the price elasticities of demand for imports and exports exceeds unity in absolute value (as per the well-known Marshall-Lerner condition) (Thirlwall, Citation2011).

In this regard, (Bagnai, Citation2010)’s study also supports Thirlwall’s law because even in the presence of structural breaks in long-run relationships, the predictive performance of the income elasticity of imports remains plausible. On the other hand, (Podkaminer, Citation2017) uses a two-stage-least-squares (2SLS) approach to test the validity of the law. Surprisingly, when estimating the parameters of the import function one has to allow data on the real exchange rate and domestic income only and there is no window to incorporate external imbalances (Podkaminer, Citation2017).

The same issue arises when estimating the parameters of the export function. This is why (Podkaminer, Citation2017) concluded that Thirlwall’s law may only be necessary to explain international growth rate differences, but not sufficient.

Some studies have proposed an augmentation of the basic law to incorporate certain other variables. For instance, (Blecker, Citation1998) argued that without disregarding external constraints to growth; fundamentally it is savings and rigid wages domestically that may act as a constraint to growth. Furthermore, to incorporate income distribution to the theory of the balance of payments constrained growth, (Blecker, Citation1998) adopts the hypothesis of markup pricing.

On the other hand, (Podkaminer, Citation2017) points out that trade that is not permanently balanced implies the presence of financial flows. Thus, the trade balance equation must be augmented at given relative prices to incorporate the dynamics of non-tradable payments. Clearly, the augmented equation would then posit growth rates expected to be consistent with the overall balance of payments equilibrium growth rate (Podkaminer, Citation2017). Furthermore, (Moreno-Brid, Citation2003) proposed the inclusion of interest payments which have been at the heart of a number of balance of payments crisis for developing countries.

This study does not include such augmentation but focuses instead on the test of Thirlwall's law's original proposition that a country's economic growth rate can be predicted positively by the performance of that country's exports and negatively by the degree of income elasticity of its imports. Essentially, this requires a focus on a country's trade balance, it's export and import of goods and services, rather than an analysis of the other components of a country's balance of payments, comprising such items as financial flows, dividend flows, interest payments and remittances.

2.3. The impact of the South African trade balance on economic growth

In the period prior to 1994, South Africa's apartheid regime was relatively inward-looking, although despite partial economic sanctions the apartheid economy did enjoy significant trade links with the rest of the world. Post-apartheid South Africa's economic stance has generally become increasingly open, although the data indicates a somewhat mixed performance. Import penetration has increased from 14% in 1970–17% in 1998 (Vaze, Citation2000), but the contribution of South African exports as a share of world trade declined over the period from 1980 to 2008 (Visser, Citation2009).

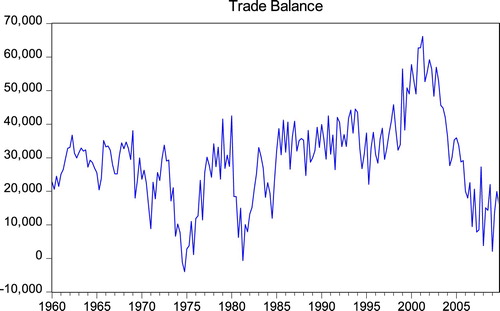

Based on SARB dataFootnote1 , South Africa’s trade balance shows a long-term upward trend although recent performance has been negative. In the 1960s, even though unstable, the country witnessed high trade surpluses. In 1974 as well as in 1981, the trade balanced was plunged into a deficit. In the late 1980s up until the year 2000, South Africa enjoyed significant improvements in the trade balance, such that by the year 2000 international trade constituted approximately 16 percent of the GDP (Smit, Citation2006).

Since the year 2002, South Africa’s trade balance has been on a marked negative trajectory. If the trend continues, the trade balance is likely to be the largest contributing component to the current account deficit. The trade balance accounted for 26 percent of the current account deficit between 2004 and 2013 and is likely in future to surpass the 37 percent of the current account deficit attributed to net payments to foreign investors over the same period (Strauss, Citation2015). This is driven largely by the fact that the growth in export volumes has been relatively low. For example from 2000 to 2007, growth in export volumes averaged 3.9% per year (2000–2007) (Edwards and Lawrence, Citation2012).

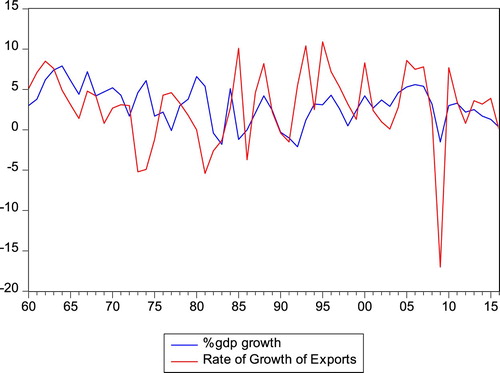

Despite periods of growth, as depicted in , South Africa has experienced a long-run downward trend in its economic growth performance. Interestingly, descriptive data show over time that the growth rate of exports and the growth rate of the economy tend to move in the same direction. This is noteworthy as such export performance is one of the key elements that will be taken into account in this study’s formal testing of the applicability of Thirlwall’s law in the South African context (Thirlwall, Citation2011).

3. Formal presentation of Thirlwall’s law

It is assumed that trade is balanced in the long-run. In addition, it is assumed that the real exchange rate is balanced in the long-run and that it moves with output growth. These assumptions imply that the values are taken at equilibrium or steady state. The balance of payments equilibrium on a country’s current account, or more accurately trade account, may be expressed follows, as in (Thirwall, Citation1979):(1)

(1) Where

represents the domestic price of exports in national currency, X – quantity of exports,

- the foreign price of imports in foreign currency, M – quantity of imports and E – exchange rate, and t represents time. Importantly, non-price competitiveness is assumed for the long-run implying that differences in relative prices can only affect short-run growth and in the long-run the exchange rate is balanced (Setterfield, Citation2011).

Thirlwall (Citation1979) argues that the balance of payments equilibrium through time requires that the rate of growth of the value of exports equals the rate of growth of imports, expressed as follows;(2)

(2) Where the lower cases represent continuous rates of change of the variables. The openness of the economy implies that it is prescribed by two conventional demand equations; one for its exports and the other for its imports and both in real terms (Podkaminer, Citation2017). Therefore, the import demand relation may be given as a multiplicative function of imports, the price of import substitutes, and domestic income:

(3*)

(3*) Where

represent the price elasticity of demand for imports,

– cross-price elasticity of demand for imports, Y – domestic income and

– income elasticity of demand for imports. Then, the rate of growth of imports, which is derived by linearising (3), may be expressed as:

(4*)

(4*) Again, the lower cases represent continuous rates of change of variables. The quantity of exports may be stated as a multiplicative function of the price of exports in foreign currency, the price of goods competitive with exports, and the level of world income;

(5)

(5) Where

represents quantity of exports,

– domestic price of exports,

– price of goods competitive with exports, Z – level of world income,

– foreign price of domestic currency,

– price elasticity of demand for exports,

cross-elasticity of demand for exports and

– income elasticity of demand for exports. Then, the rate of growth of exports may be expressed as;

(6)

(6) Substituting (4) and (6) into (2) allows for a solution for the growth rate of domestic output consistent with the balance of payments equilibrium growth rate (

).

(7)

(7) Furthermore, if the Marshall-Lerner condition holds or relative prices measured in a common currency do not change in the long-run, then equation (7) can be expressed as follows:

(8)

(8) Equation (8) is famously called Thirlwall’s law and states that the estimated growth rate of an economy is proportional to the growth rate of exports

divided by the income elasticity of imports

.

4. Discussion of results when testing Thirlwall’s law using South African data

The central hypothesis of Thrilwall’s law is that the rate of economic growth can be predicted by the growth rate of exports (which impacts positively on the rate of economic growth) and the income elasticity of demand for imports (which impacts negatively on the rate of economic growth). To test this empirically for the South African economy, relevant data sourced from the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) from 1960 to 2016 are used.Footnote2 Firstly, a regression of equation (4)* is run using the ARDL technique to estimate . Secondly, the log of the volume of exports gives

. Thereafter,

giving the rate of economic growth predicted by Thrilwall’s law.

The import function as represented per equation (3) above can be written as a multiplicative function of the real exchange rate and income, as follows;(3)

(3) Where RER is the real exchange rate, A is a constant term,

is the real price elasticity of demand for imports and other variables are as defined above. Then natural logs are taken, the equation is differentiated with respect to time and a constant term is added to give an estimating equation of the form;

(4)

(4) From equation (4)* it is possible to derive the estimates for the income elasticity of demand for imports (π) and the error term

. The growth rate of exports

is then divided by the income elasticity of demand for imports (π) to give an estimated growth rate

predicted in terms of Thirlwall’s law. Following (Hussain, Citation1999), equation (4)* is estimated for each decade from 1960 to 2009 using the ARDL technique to capture long-run and short-run dynamic relationships in the model.

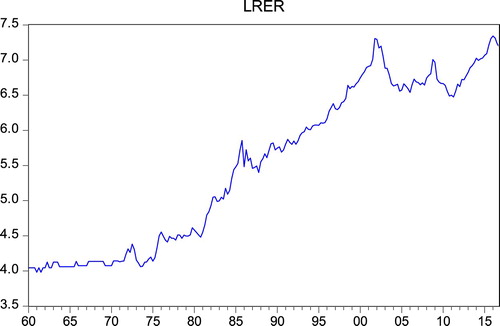

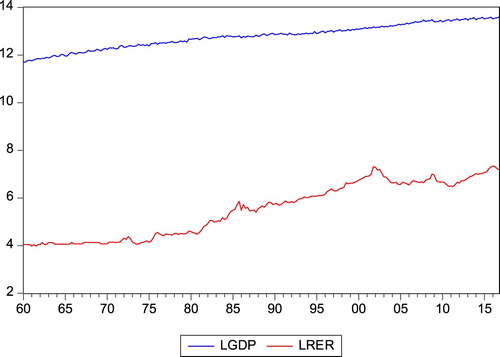

below shows that from 1960 to 2016, the real exchange growth rate for South Africa lies between 4.00 and 7.50, indicating that there is an upward trend in the real exchange rate over time. The upward trend is inconsistent with the assumption that the real exchange rate is constant in the long-run (Cruz, Citation2000). Additionally, in below it is noted that in the long-run the growth rate of output and the real exchange rate move together and that is consistent with Thirlwall’s assumption. The real exchange and GDP are logged to find the growth rate of the real exchange rate (LRER) and output growth rate (LGDP).

Due to the dynamic long-run relationships in the model, the augmented Dickey-Fuller test is used to test for stationarity. shows unit root tests for stationarity in the long-run variables; the growth rate of imports, growth rate of the real exchange rate as well as the growth rate of income. The Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC) is used for the diagnostics. At level, the Augmented-Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test statistic is insignificant which indicates the presence of unit roots in all three variables. At first difference, the growth rates of imports (LMT), LGDP and the LRER are found to be stationary. Thus, all the variables are cointegrated of order one.

Table 1 . Unit Root Test for stationarity.

The signs of the coefficients during these periods confirm Thirlwall’s law. The coefficient of lgdp is found to be positive and significant while the coefficient of lrer is found to be negative and significant. This shows that increases in income lead to increases in imports and depreciation of the real exchange rate decreases imports. However, during some periods, the income elasticity of imports is high, for instance in the period 2000–2009, it was found to be 1,824552. This meant that exports needed to grow at an average of approximately 6.59 for the estimated growth rate to be equal to the actual average growth rate.

To be certain about the presence of a long-run relationship between the variables, an ARDL long-run form and the bound test was conducted. The F-statistic of the bounds test is below each of the reported critical values, and thus the null hypothesis cannot be rejected that there is no long-run relationship between the variables. Moreover, the model's specification is determined by conducting Ramsey reset tests by which it is found that the p-value (0.4087) is greater than the 1% significance level and as such, the model is considered to be correctly specified. Furthermore, the normality graph indicates that the residuals are normally distributed.

below illustrates a comparison for each decade of the actual growth rates (Ga) with the growth rates estimated by Thirlwall’s law (the balance of payments equilibrium growth rate, ) without adjusting for the years the economy experienced structural breaks.

Table 2 . South Africa – Calculations of the growth rate consistent with the growth rate of the balance of payments equilibrium.

From , it can be seen that the actual average growth rate moves with the estimated growth rate of the balance of payments equilibrium. Notably, the period 1990–1999 is excluded from the table because the income elasticity of demand for imports shows an unexpected negative sign and the period 2010–2016 is excluded, as it is incomplete.

For robustness, below illustrates a comparison for each decade of the actual growth rates (Ga) with the growth rates estimated by Thirlwall’s law once the data has been adjusted to deal with the impact of structural breaks. Structural breaks are likely because the South African economy has experienced several business cycles of varying durations (Gujarati, Citation2009).

Table 3 . South Africa – Calculations of the growth rate consistent with the growth rate of the balance of payments equilibrium adjusted for structural breaks.

The Chow Breakpoint test was used to evaluate structural breaks in the data. The test for joint significance shows that the years 1973 and 1995 have had major breaks, which significantly affect the data. To deal with the matter of structural breaks, the data is split and regressions are run from both sides of the year that experienced structural breaks, and data from 1970 to 1974 is removed since its insignificant. Furthermore, the Breusch–Godfrey test result shows no serial correlation in the model since the p-value (0.5484) is greater than 5 percent level of significance and suggests the absence of autocorrelation. The results show improvements in that the growth rates estimated by Thirlwall’s law better explain the actual average growth rates.Footnote3

To test for the predictive power of the Thirlwall’s model (Swales, Citation1985) method is used, which requires that, the regression of the actual growth rate (Ga) on the predicted growth rate. According to this method, if the regression coefficient equals one and the constant term equals zero, statistically then the predicted growth rate

is to be considered a good estimate of the actual growth rate (Ga). Results of the regression

are shown in .

Table 4 . Results of the Wald Test.

Without adjusting for structural breaks, (Ga) is regressed on , with the null hypothesis that the coefficient of the regressor

is unit and the constant term is zero jointly. The Wald test showed a p-value of 0.3727, and as such, the null cannot be rejected at 5% level of significance.

When adjusted for structural breaks, the predictive power of Thirlwall's law improves. The Wald test showed a p-value of 0.5479, as such, the null is rejected in favour of the alternative hypothesis that the coefficient of the regressor is unit and the constant is statistically equal to zero. At 5% level of significance, these results are consistent with Thirlwall's law, which states that a country’s economic growth rate can be explained positively by the performance of its country’s exports and negatively by the degree of income elasticity of its imports.

5. Conclusion

The results of this paper support the applicability of Thirlwall’s law to the South African economy. A powerful implication of this finding is that the country will improve its economic growth rate if it successfully implements policies to promote its exports and constrain the income elasticity of its imports.

At a policy level policy, this finding has implications for strategies aimed at increasing the competitiveness of the South African economy as well as to trade promotion strategies. This lends support to policy prescriptions that argue for an export-led approach to stimulating economic growth in South Africa (Lawrence, Citation2006).

An important insight implied by this finding is that if an economy is to benefit from the increased levels of aggregate demand predicted by Thirlwall's law, that is, when exports rise and the income elasticity of imports falls, then pro-competitive supply-side reforms may be an important a pre-condition.

Competitiveness can be achieved through a range of interventions, which have the effect of reducing the costs of production, making an economy more internationally competitive and place in a position to benefit from external demand factors. Such intervention would include a competitive real exchange rateFootnote4, not eroded by domestic inflation (Freytag, Citation2008), a competitive wage structure and general re-enforcement of a low-cost-base for production including through the provision of reliable and efficiently managed energy and logistical platforms.

A further policy implication is that there is likely to be a significant growth dividend to be gained for the South African economy from the expansion of well-designed trade relations with various trading blocs. Some of these relations include with Southern African Development Community (SADC), the incipient African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCTA), the European Union and Britain, with various BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China), as well as via preferential trade access under the United States’ African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) arrangement.

Such strategies of expanded trade relations will likely lead to an increased flow of both exports and imports. Importantly, agreements must be well constructed to promote South African exports into a wide range of markets around the globe combined with the ongoing development of South Africa's own industrial capabilities. A key finding of this study is that the net effect of such agreements is likely to be positive for South Africa's overall economic growth rate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The following South African Reserve Bank data series are utilized in this study. The volume of imports from the SARB series 5034 is used. For the growth rate of exports, the SARB time series 6013 is used. For the price of imports, SARB series 5035 is used and for the price of exports SARB, series 5031 is used. For the nominal exchange rate, end of quarter data from SARB series 5339 is used. For the income proxy, expenditure on GDP in real terms from SARB series 6045C is used. To calculate the rate of GDP growth percentage change SARB series 6006 is used.

2 As above, the following SARB data series are used for the volume of imports SARB 5034, for the growth rate of SARB 6013, for the price of imports SARB 5035, for the price of exports SARB 5031, for the nominal exchange rate SARB 5339, for expenditure on GDP in real terms SARB 6045, and for GDP growth SARB 6006. Various stationarity tests indicate that in the general the growth rates of imports and income, as well as changes in the real exchange rate are stationary after first differencing. All the data is seasonally adjusted.

3 The period from 1970 to 1972 is not included as the income elasticity of demand for imports is insignificant at 5 percent level of significance.

4 A study conducted by (Kabundi, Citation2014) showed evidence for South Africa that net exports, boosted by a weaker real effective exchange rate, improved the trade balance in the period 1994–2011.

References

- Bagnai, A, 2010. Structural changes, cointegration and the empirics of Thirlwall's law. Applied Economics 42, 1315–29. doi: 10.1080/00036840701721299

- Blecker, R, 1998. International competitiveness, relative wages, and the balance-of-payments constraint. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 20, 495–526. doi: 10.1080/01603477.1998.11490166

- Cruz, JL, 2000. Thirlwall’s law” and beyond: The Latin American experience. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 22, 477–95. doi: 10.1080/01603477.2000.11490253

- Dutt, AK, 2006. Aggregate demand, aggregate supply and economic growth. International Review of Applied Economics 20, 319–36. doi: 10.1080/02692170600736094

- Edwards and Lawrence, 2012. South African trade policy and the future global trading environment. South African Institute of International Affairs, Johannesburg.

- Elish, E, 2018. An examination of the empirical validity of the Thirlwall ‘law’: The case of Egypt. International Journal of Business and Economics Research 7(6), 203–11.

- Freytag, A., 2008. Balance of payments dynamics, institutions and economic performance in South Africa: a policy-oriented study. Trade and Industry.

- Gujarati, DC, 2009. Basic econometrics. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, New York.

- Hein, LV, 2008. Distribution and growth reconsidered: empirical results for six OECD countries. Cambridge Journal of Economics 32, 479–511. doi: 10.1093/cje/bem047

- Hussain, MN, 1999. The balance-of-payments constraint and growth rate differences among African and East Asian economies. African Development Review 11, 103–37. doi: 10.1111/1467-8268.00006

- Kabundi, ES, 2014. The exchange rate, The trade balance and the. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 17, 601–8.

- Lawrence, LE, 2006. South African trade policy matters: Trade performance and trade policy. the National Bureau of Economic Research 16, 1–62.

- León-Ledesma, MA, 1999. An application of Thirlwall’s law to the Spanish economy. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 21, 431–39. doi: 10.1080/01603477.1999.11490206

- Lima, Ra, 2007. A structural economic dynamics approach to balance-of-payments-constrained growth. Cambridge Journal of Economics 31, 755–74. doi: 10.1093/cje/bem006

- Lima, 2010. Structural change, balance-of-payments constraint, and economic growth: Evidence from the multisectoral Thirlwall's law Raphael Rocha Gouvea. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 33, 169–204. doi: 10.2753/PKE0160-3477330109

- Mankiw, DR, 1992. A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, 407–37. doi: 10.2307/2118477

- Moreno-Brid, JC, 2003. Capital flows, interest payments and the balanceof-payments constrained growth model: a theoretical and empirical analysis. Metroeconomica 54, 346–65. doi: 10.1111/1467-999X.00170

- Palley, TI, 2012. The rise and fall of export-led growth. Facultad de Economía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 71, 141–61.

- Pilley, TI, 1996. Growth theory in a Keynesian mode: Some Keynesian foundations for new endogenous growth theory. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 19, 113–35. doi: 10.1080/01603477.1996.11490100

- Podkaminer, L, 2017. ‘‘thirlwall’s law’’ reconsidered. Empirica 44, 29–57. doi: 10.1007/s10663-015-9310-6

- Porcile, LB, 2002. Balance-of-payments-constrained growth in Brazil: a test of Thirlwall's law, 1890–1973. Journal Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 25, 123–40.

- Setterfield, 2003. Supply and demand in the theory of long-run growth: Introduction to a symposium on demand-led growth. Review of Political Economy 15, 23–32. doi: 10.1080/09538250308440

- Setterfield, 2011. The remarkable durability of Thirlwall’s law. PSL Quarterly Review 64, 393–427.

- Smit, B, 2006. The South African current account in the context of SA macroeconomic policy challenges. The South African Reserve Bank, Johannesburg.

- Solow, 1956. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 50(1), 65–94.

- Strauss, I, 2015. Understanding South Africa’s current account deficit: The role of foreign direct investment income. Africa Economic Brief 6(4), 1–14.

- Swales, PG, 1985. Professor Thirlwall and balance of payments constrained growth. Applied Economics 17, 17–32. doi: 10.1080/13691066.1985.603617

- Thirlwall, A, 1979. The balance of payments constraint as an explanation of the international growth rate differences. PSL Quarterly Review 32, 1–5.

- Thirlwall, 2011. Balance of payments constrained growth models: history and overview. PSL Quarterly Review 64, 307–51.

- Vaze, JF, 2000. The nature of South Africa’s trade patterns by economic sector, and the extent of trade liberalization during the course of the 1990s. Economic Research Southern Africa 69, 436–78.

- Visser, LR, 2009. Note on global growth, international trade and South African exports. South African Reserve Bank, Pretoria.