ABSTRACT

The living conditions studies (LCS) on disability are a survey method that has been used in a standardised manner across eight countries in southern Africa. This paper discusses an evaluation of the LCS that were carried out between 2000 and 2015. The methodology of this evaluation was a desk top study as well as interviews with relevant stakeholders from each of the countries. Results of the desk top study show an upward trend in citations for countries which have been cited in the literature, and that the scholarly as well as the grey literature reveal a clear trend that certain countries tend to dominate in uptake coverage. Results from the interviews generally show that the surveys were accepted by all countries in a positive and favourable light. Each country, with their unique context, has their own story. Recommendations based on the evaluation are discussed.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Disability has historically not been sufficiently considered as part of the international development agenda, though matters are improving to some degree (Mitra, Citation2018). As Cieza et al. (Citation2018) mention, disability is gaining prominence in the development agenda in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations [UN], n.d.) and elsewhere. However, the UN Flagship Report on Disability and Development (UN, Citation2018) indicate that persons with disabilities are not yet ‘sufficiently included in the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the Sustainable Developmental Goals’ (UN, Citation2018:24). Given the fact that, according to the World Report on Disability (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2011), approximately 15% of the world’s population has some form of impairment affecting functioning, and given the association between poverty and disability which, though complex, is well established (Mitra, Citation2018), there is an important need to obtain good quality data on persons with disabilities lives and conditions of living in low- and middle-income countries in particular. Most of what we know about disability comes from the Global North. The need for high-quality data about the situation for people with disabilities has been highlighted by many authors (Elwan, Citation1999; Metts, Citation2000; Yeo & Moore, Citation2003; Eide, Citation2010) as well as the UN (Citation2009) report on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and disability. People with disabilities in developing countries are over-represented among the poorest people and have been largely overlooked in the development agenda (Wolfensohn, Citation2004). The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, Citation2006) states that there is a need for information, data collection and research on the situation of people with disabilities, particularly in developing countries (Eide et al, Citation2011). While most people with disabilities live in developing countries (Yeo & Moore, Citation2003), little has been done in the Global South. Given this context, starting nearly two decades ago, The Norwegian Federation of Organisations of Disabled People (FFO) approached SINTEF, a national Norwegian research foundation, to begin a series of studies of living conditions of persons with disabilities in southern Africa. These studies, which came to be known as the ‘living conditions studies’ (LCS), were conducted in a number of countries, in each case in partnership with the country-level Disabled People’s Organisation (DPO) and with the southern African Federation of the Disabled (SAFOD), which is an umbrella body representing the DPOs in ten southern African countries. LCS were undertaken in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Zambia, Mozambique, Lesotho, Swaziland and Botswana. These large scale studies compare the living conditions of disabled and nondisabled persons in these eight countries. The surveys in the southern African region provide a first comprehensive, systematic approach to living conditions among people with disabilities in developing countries that make is possible to compare groups as well as make comparisons across different contexts (Eide et al., Citation2011). Good quality statistical data from the surveys have the potential to provide planning opportunities for effective and equitable service delivery, policy development and the establishment of priorities in terms of the rights of people with disabilities (Eide et al., Citation2011).

The four main objectives of the LCS were:

to develop a strategy and methodology for the collection of comprehensive, reliable and culturally adapted statistical data on living conditions among people with disabilities;

to provide organisations for people with disabilities, as well as local, regional and national authorities, with up-to-date documentation on the state of living conditions among people with disabilities;

to include and involve people with disability in every step of the research process;

to initiate a discussion on the concepts and understanding of ‘disability’, in particular in the perspective of developing countries (Loeb & Eide, Citation2006).

The Namibian survey was carried out in 2001–2002, Zimbabwe in 2002–2003, Malawi in 2003–2004, Zambia in 2005–2006, Mozambique in 2007–2008, Swaziland and Lesotho in 2009–2010 and Botswana in 2011–2014. A second survey in Malawi is being completed in 2018, and another in Uganda – these fall out of the scope of the present review. The variables that were measured in each survey can be divided into the ‘Household level’ and the ‘Individual level’. Variables in each level are highlighted in .

Table 1. Variables measured in each survey per household and individual levels.

The costs for each survey (bearing in mind some variation due to the size of samples, etc.) was between USD 450 000 and USD 500 000.

In 2007, an evaluation of the scientific validity of the Zambian study (Bjørkhaug, Pedersen, & Bøås, Citation2007) was carried out. This evaluation, which was initiated by FFO due to requirements from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) and carried out by Fafo,Footnote1 focused on methods used and the relationships between these, and conclusions drawn. An investigation into the broader social impact of the LCS as a whole has, however, never been previously carried out. In 2016, we were approached by FFO to examine the social and political impact, and lessons learned, from the LCS in southern Africa. The project was conceived of as a desk top review.

We report here on key findings from our report, with particular emphasis on:

Uptake of the LCS findings in research literature;

Impact of LCS in Norwegian development efforts;

Impact of LCS as reported by DPOs;

Impact of LCS more broadly in the countries and the region.

2. Methods

As requested by FFO, the methodology used in this evaluation was primarily a desk top study. We decided, however, to supplement a desk review of all information (including grey literature) that we could source on the LCS, with stakeholder interviews conducted by the first author.

2.1. Desk top study

The desk top study explored the extent to which the LCS have been cited in the research literature both scholarly and grey literature. For this purpose, we decided to use Google Scholar as opposed to databases such as Web of Science or SCOPUS, for example. We made this choice because Google Scholar accesses the widest range of outputs in the widest range of formats.

2.2. Interviews

The first author attended a SAFOD meeting in Johannesburg, travelled to Malawi, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe for further interviews, and conducted telephonic interviews where face to face interviews were not possible. We did not interview current SINTEF staff because of possible bias in evaluation of the impact of their work. We did, however, interview a former SINTEF researcher, Dr Mitch Loeb, who has first-hand experience of the studies, for background information. In all countries, we attempted to interview government representatives; only in Malawi did we succeed in setting up these interviews. We also approached the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and NORAD, but they did not respond.

The interviews were all exploratory and qualitative in nature. An open-ended semi-structured interview schedule was developed with questions based on addressing the background and objectives of the LCS. Interviewees included stakeholder representatives from all countries (except Swaziland), a SAFOD representative and a former SINTEF researcher. Details of interviewees are presented in . The transcribed qualitative data were analysed using thematic content analysis where themes and sub-themes were identified and analysed.

Table 2. Interviews conducted October 2016–December 2016.

In order to triangulate findings as much as possible, we sent a draft of the current article to both SINTEF and FFO for comments.

3. Results

3.1. Desk top study

3.1.1. Scholarly literature

The Google Scholar search revealed a total of 250 citations of the eight LCS reports. Of the 250 citations, 192 were in English and 58 in other languages. The country by country citation analysis is presented in .

Table 3. Citations by country.

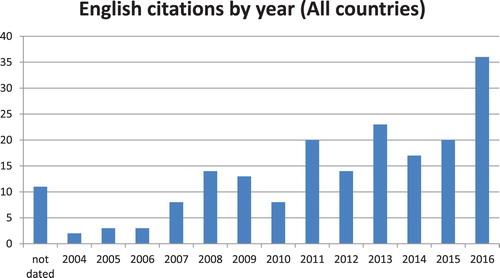

It is noteworthy that the general annual trend of citations for 2004–2016 is in an upward direction, as shown in . This suggests strongly that citations will continue to increase into the future.

In summary, there appears to be an upward trend in citations for countries which have been cited in the literature, but three country reports are not cited in literature indexed in Google Scholar.

3.1.2. Grey literature

The LCS are cited in a number of documents which have been used to take disability research and policy further, for example:

Disability Policy Audit in Namibia, Swaziland, Malawi and Mozambique, Raymond Lang, 2008.

Technical Paper for UNESCO Meeting on Disability Data and Statistics, Arne Eide, 2014.

Living Conditions among People with Disabilities in Southern Africa, pamphlet, not dated.

Disability, Living Conditions and Quality of Life. The Case of the Municipality of Anapoima in Rural Colombia, Arango Restrepo Jose Fernando, Master’s Thesis, 2015.

Research on People with Disabilities in Zambia: Recent Experience and Findings, Mitchell Loeb, presentation not dated.

Living Conditions among Persons with Disabilities Survey – Key Findings Report, Unicef, 2013.

It is important to note that in the international arena, the LCS were cited 23 times in the World Disability Report of 2011. This is a major document summarising global knowledge regarding disability

There is a clear trend, as in the scholarly literature, that certain countries (Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Namibia) tend to dominate in uptake coverage.

3.1.3. Impact of LCS in Norwegian development efforts

In Norway, the process of including disability issues in development co-operation started some years before 2000, and in 1999 the Norwegian Government stated that greater emphasis would be placed on measures for persons with disabilities (Mattioli, Citation2008). The overall objective of Norway’s development policy is to fight poverty and achieve a fairer distribution of resources and opportunities. The Norwegian development strategies with respect to disability are in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Despite a number of attempts to contact the relevant Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and NORAD, we did not receive replies. We also scanned online literature to look for mention of the LCS in Norwegian development efforts and policy, but we found no evidence of this. This does not necessarily mean that there was no impact of the LCS on such efforts, but we did not find any information in this regard.

3.2. Interviews

3.2.1. Impact of LCS as reported by DPOs

3.2.1.1. General comments on the value of the LCS

Generally, the surveys were accepted by all countries in a positive and favourable light. For example, Malawi stakeholders mentioned that the LCS data provided ‘evidence’ for policy influence, establishment of programmes, planning, writing proposals, changing mind-sets, and the stimulus for many discussions on disability. The general consensus from Zambia was that the survey report does get used and referred to in the DPOs themselves – from planning, budgeting, awareness raising to writing proposals, and is used in ‘all corners of the country’. There had been ‘increased interest’, ‘networking’ and ‘working together’ among stakeholders when it came to research on disability issues – ‘it created a kind of a platform where these stakeholders can start meeting and discussing’. According to Mozambique, there has been dialogue, improved relationships between stakeholders, policy development and planning, as well as concrete measures put in place emergent from the survey.

There was general agreement that despite the surveys being generally positive and providing much needed data, there still needs to be further monitoring and evaluation, and a plan to use the data in the future. But, according to a Malawian stakeholder, there seems to be a ‘lack of resources to continue the process’. According to Zambian stakeholders, little emanated from the dissemination of the results, and the general opinion was that there has been no development of concrete measures since the survey was carried out. Based on the above, the group agreed that there was no monitoring process of the survey in place in Zambia. The reason given for this was that there was once again no funding available. As one Zimbabwean stakeholder concluded, SINTEF ‘didn’t provide a way forward for the survey. So, it was like something that was just done, and then it is gathering dust somewhere … on the shelves’. The stakeholder from Lesotho summarised: ‘ … much has been done in terms of investing in the development of the survey, but not that much has been done to make sure that the results of the study are being implemented accordingly’.

3.2.1.2. The influence of differing country contexts

The context and the socio-political situation of each country also plays an important role in the impact of the LCS. This can be seen, particularly, in Zimbabwe. According to a Zimbabwean representative, the document was a ‘hot topic’ for three years following the survey in 2003, but after that nothing happened with regard to it – ‘thereafter, I think it became something which was put on silence. It was buried. Yes. It was actually cremated’. He went on to explain why this had happened:

Because after it has been published, we found ourselves as Zimbabweans in a very unprecedented economic situation in the height of 2008. So, everything was overtaken by events and we were only focusing on, not on living conditions, but on just how to survive. Whether, at one level, I think it’s affected people from focusing on other things.

The Botswana stakeholder emphasised that the study was supported by the Office of the President in Botswana, and not by the Federation of the Disabled, and hence did not involve persons with disabilities. DPOs are still waiting to see the report and assess its impact on the country. For instance, according to the representative, there has been no dialogue or discussion between relevant stakeholders concerning the results of the study in the country. The reason for the limited role of SAFOD and BOFOD was due to internal problems in SAFOD in particular at the time of the survey.

3.2.1.3. Impact on the lives of persons with disabilities

Regarding the important issue of improving the living conditions of persons with disabilities in the countries, the general opinion from the stakeholders was that there was no improvement and, if there was any, it was minimal. Malawi stakeholders mentioned that the improvements were ‘slight’, while Zambia stated that it was ‘difficult to point out’ if there was any improvement in the lives of persons with disabilities in Zambia. Zimbabwe felt that the living conditions had actually deteriorated since the survey, due to economic and political circumstances in the country, while most of the other countries reported no improvement.

3.2.2. Impact of LCS more broadly in the region

3.2.2.1. Participation of persons with disabilities in research and policy efforts

Participants across the board commented on the role the LCS played in increasing the participation of persons with disabilities in the research processes. According to Dr Loeb, a key lesson from the LCS, which has had global influence (as evidenced in the prominence of the LCS in the World Disability Report, as mentioned above), was that it was possible and desirable in low-income countries to facilitate the meaningful inclusion of persons with disabilities in the research process as a whole. This, according to Dr Loeb, ‘created a dynamic that I don’t think ever existed before’.

Another impact, according to Dr Loeb, was that the survey studies set up a model for future international disability research – especially regarding the shift from the MDGs to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and disaggregating all development outcomes by disability status.

3.2.2.2. Relationships between DPOs and academic institutions and other networks

The LCS studies built relationships with disability communities, but also more broadly. Relationships with academic institutions were created. This was for Dr Loeb ‘the second most impactful area’. Creating these collaborations that developed over time gave sub-Saharan Africa a strong base of academic research, and research in which there were new partnerships between universities and the disability sector. The African Network of Evidence to Action on Disability (AfriNead), which has had five regional conferences and which established the African Journal of Disability,Footnote2 continues to depend and build on relationships and partnerships established through the LCS. The Washington Group on Disability Statistics,Footnote3 which falls under the United Nations Statistical Commission, has, according to Dr Loeb, who is part of the group, been strongly influenced by the LCS. This is so, not just in terms of data collected, but in terms of ways of involving DPOs in research and data-gathering processes.

Following the LCS process, SINTEF is recognised globally as a key player in the field of disability statistics and research. As Dr Loeb puts it:

You could think of them (each LCS study) each as individual national projects to collect data to support national infrastructure, but there is a much broader regional international impact to this work. I mean, if you think of that fact that not only does the Washington Group reference the work of SINTEF, but SINTEF, through the work that they’ve been doing, is invited to international forums all the time.

3.2.2.3. Comments on findings by SINTEF and the funder (FFO)

Both SINTEF and FFO were given the opportunity to respond to the findings. SINTEF made some minor suggestions for changes in order to improve clarity, but did not question the findings substantively. The representative of FFO, however, noted that, subsequent to all LCS surveys, there were Awareness Building Campaigns (ABC), some lasting over a number of years after the survey. Based on this, the FFO representative questioned the view that not much was done in terms of dissemination. The representative commented further that local DPOs carry some responsibility themselves in taking forward the lessons learned from research undertaken.

4. Discussion

A strength of the LCS is that they use comparable methodology in the eight different countries and that comparison between countries is therefore possible. It is clear that on a country for country basis, the LCS has had varied success and uptake. Each country has their own unique story about how the survey study has impacted, or not impacted, on them. Some countries, such as Malawi and Zambia, seem to have experienced more impact than others. The reasons for this are numerous, but it is all fundamentally based on the support networks (in particular, government support), the infrastructures of the countries, including the leadership within the disability sectors, as well as the approach of stakeholders. For example, Malawi was well supported by their government and had strong leadership through the disability sectors, while Botswana lacked support networks and tended to have stakeholder issues regarding the release of the findings. It does not seem reasonable to consider the impacts of the LCS without a consideration of the broader context in each country. We suspect that studies in other sectors would have similar varying uptake in different countries, and a method not used in the current study could be to compare the LCS uptake with the uptake of other studies on a country by country basis. It is recommended, therefore, that each country be addressed on their own merit and that sweeping generalisations not be made across the survey studies in the eight countries.

The main issue that was highlighted by most countries is that the process set in motion by the LCS needs to be a continuous process and not a once-off intervention. In this regard, participants in our evaluation highlight another issue which is key to development work in general, namely that projects are commonly conceptualised individually, but they form part of a history of engagement amongst a complex network of players. With regard to the LCS in particular, a common theme from participants we spoke to was a lack of ongoing monitoring capacity and application in most countries. This view was expressed despite the funding organisation having funded awareness campaigns. The representatives felt that the survey studies could be ‘taken to another level’, but realise that funding and local capacity is an obstacle. This is a complex challenge going forward but one worth taking up – local, meaningful and useful data-gathering as part of an ongoing reflexive practice for countries remains an elusive goal at present. This is supported by Eide et al. (Citation2011) who state that a monitoring system is simply not in place in low-income countries.

We were not able to ascertain the impact, if any, of the LCS on Norwegian development efforts, and while absence of evidence in this regard, as elsewhere, is not evidence of absence of impact, the lack of information may speak to the continuing siloed nature of disability research – despite the inclusion of disability in the SDGs, there may be some difficulty integrating disability-related findings into broader development initiatives.

By contrast, within the broader global field of disability and disability statistics, the LCS are prominent in both the World Disability Report and in the work of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics, as well as in other fora. This is a substantial impact for a series of rather small studies in one region of the world.

There have been other positives coming out of the LCS. As has been stated, the strong involvement of DPOs throughout the entire research process, as well as the efforts to recruit interviewers with disabilities, has positively influenced the relevance and applicability of the data (Eide et al., Citation2011). This falls in line with capacity building initiatives and development issues. However, despite there being many strengths in these studies, there are some issues regarding difficulty in infrastructure and capacity in general, for example, the LCS used individuals who were inexperienced in research and hence the quality of data may have been somewhat affected (Eide et al. Citation2011).

One issue which is an overarching one concerning the LCS is that the studies were not designed with an explicit plan or framework to create or measure impact. The broad field of translation science, or knowledge translation, which is concerned with the question of how to translate research findings into action, has great relevance here (Kent, Hutchinson & Fineout-Overholt, Citation2009; Grimshaw, Eccles, Lavis, Hill & Squires Citation2012; Jones, Roop, Pohar, Albrecht & Scott, Citation2015). Generally speaking, though, knowledge translation and translation science focuses on broader implementation of interventions studies. The LCS studies were not designed as interventions as such – they were descriptive studies of living conditions. Implicitly, though, the LCS were concerned with creating social change, and the principles of how to design research in such a way as to maximise impact could well have been useful. It does need to be recognised, though, that the field of knowledge translation has grown remarkably very recently, and it is not fair to judge work from a few years ago against this contemporary trend, though this may be an important issue for the future.

Given these considerations, we provide a summary of key lessons learned through this process:

It is important not to make very broad generalisations about the impact of the research across the surveys – each country has their own dynamics, and hence impact. While some countries seem to have had very successful impact, there are others that have had less successful impact. This is a contextual factor not under the control of the LCS.

Countries where there has been good collaboration between stakeholders, strong leadership within DPOs and more government involvement have shown to be more successful in terms of impact. The more stakeholders are involved (importantly, with the inclusion of government), the more it is possible for more long-term impact. This impact is reflected in both the qualitative stories from key stakeholders as well as the quantitative data reflected in the scholarly impact.

As the Zimbabwe case showed, probably most clearly, the impact of the survey has much to do with the current political, economic and social circumstances of a country. Context is thus important. They believe that the impact could have been stronger and more sustained had Zimbabwe not experienced such a high degree of instability soon after the survey was completed.

Despite the inter-country differences, discussed above, the LCS process was experienced as a very good advocacy tool which highlighted disability issues in most countries.

The gap between policy and implementation (again, a well-recognised problem in development work) was clear. There is evidence of policy developments following the LCS, but this was not always transferred into implementation of programmes.

The issue of long-term impact remains a major challenge. The surveys had the potential to put longer-term monitoring in place, but lack of funding and resources were highlighted as key issues inhibiting the implementation of a more longitudinal, ongoing approach.

Despite this challenge, it was demonstrated that there were clearly broader and indirect impacts of these studies. These included the training and development of people in disability studies – from the training of fieldworkers to the qualifications of various degrees to persons at university institutions. This survey study has thus widened the human resource capacity and knowledge capacity internationally in disability studies.

It is clear that the impact of the LCS goes beyond the boundaries of the countries that participated in the surveys. From our data collected for this evaluation, and from our own engagement in the field, we are convinced that these small studies have had a global impact on disability and development work, which should not be underestimated. One should not only consider the results of the research itself but also the impact of this research.

5. Recommendations

Based on these key findings, we make the following recommendations:

The key success of the LCS, which is in the area of process – of inclusion and participation by persons with disabilities in research, of developments in creating partnerships between DPOs and other role-players – should be celebrated and highlighted in the form of policy briefs which could be disseminated in Norway and further afield.

The question of uptake and problems with uptake, especially in low-resource contexts, need to be considered more broadly than at the level of the LCS. We suggest that the case of the LCS possibly be used as a basis for broader dialogue around this issue.

The need for a Disability Resource Centre in southern Africa, as identified by the LCS aims, remains, and it would seem that this would require more ongoing high-level research and monitoring capacity as a partnership with DPOs. This is worth pursuing.

The issue of paying greater attention to knowledge translation methods and principles may be helpful in the future.

The global impact of the LCS on disability and development research, and the collection of disability statistics, seems considerable and is worth highlighting more than at present in pamphlets and documents. If development work is a process dependant on relationships and trust, here is an example which has been influential in a broad arena.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funders of this study- Funksjonshemmedes Fellesorganisasjon (FFO). The authors also would like to thank all the participants in the study and Jacqueline Gamble for technical assistance. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and not those of any other person or organization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Leslie Swartz http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1741-5897

Notes

2 Source: www.sun.ac.za/afrinead.

3 Source: http://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/.

References

- Bjørkhaug, I, Pedersen, J & Bøås, M, 2007. Evaluation of the report ‘living conditions among people with activity limitations in Zambia’. Fafo, Oslo. https://www.norad.no/globalassets/import-2162015-80434-am/www.norad.no-ny/filarkiv/ngo-evaluations/evaluation-of-the-report-_living-conditions-among-people-with-activity-limitations-in-zambia_.pdf Accessed 2 February 2019.

- Cieza, A, Sabariego, C, Bickenbach, J & Chatterji, S, 2018. Rethinking disability. BMC Medicine 16(1), 14. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-1002-6

- Eide, AH. 2010. Community-based rehabilitation in conflict and emergency. In E Martz (Ed.), Trauma rehabilitation after war and conflict: Community and individual perspectives. Springer, New York.

- Eide, AH, Loeb, ME, Nhiwatiwa, S, Munthali, A, Ngulube, TJ & Van Rooy, G. 2011. Living conditions among people with disabilities in developing countries. In AH Eide & B Ingstad (Eds.), Disability and poverty: A global challenge. The Policy Press, Bristol.

- Elwan, A, 1999. Poverty and disability. A survey of the literature, social protection discussion paper series no 9932. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Grimshaw, JM, Eccles, MP, Lavis, JN, Hill, SJ & Squires, JE, 2012. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implementation Science 7(1), 50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50

- Jones, CA, Roop, SC, Pohar, SL, Albrecht, L & Scott, SD, 2015. Translating knowledge in rehabilitation: systematic review. Physical Therapy 95(4), 663–77. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130512

- Kent, B, Hutchinson, AM & Fineout-Overholt, E, 2009. Getting evidence into practice–underspyltastanding knowledge translation to achieve practice change. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 6(3), 183–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2009.00165.x

- Loeb, M & Eide, AH. 2006. Paradigms lost: The changing face of disability in research. In B Altman & SN Barnartt (Eds.), International views on disability measures: Moving toward comparative measurement. Research in social science and disability. Vol. 4. Elsevier, New York.

- Mattioli, N, 2008. Including disability into development cooperation: Analysis of initiatives by national and international donors. Instituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid.

- Metts, RL, 2000. Disability issues, trends and recommendations for the World Bank, SP discussion paper no 0007. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Mitra, S, 2018. Disability, health and human development. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- UN (United Nations), 2006. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. UN general assembly A/61/611. UN, New York. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/general-assembly/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-ares61106.html Accessed 5 February 2019.

- UN (United Nations), 2009. Realizing the millennium development goals for persons with disabilities through the implementation of the world programme of action concerning disabled persons and the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities, Report of the Secretary-General A/64/180, 64th session. UN, New York.

- UN (United Nations), 2018. Realization of the sustainable development goals by, for and with persons with disabilities: UN flagship report on disability and development 2018. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2018/12/UN-Flagship-Report-Disability.pdf Accessed 3 February 2019.

- UN (United Nations), n.d. Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/# Accessed 3 February 2019.

- Wolfensohn, JD, 2004. Disability and inclusive development: Sharing, learning and building alliances. Remarks at the 2004 World Bank International Disability Conference, 1 December, Washington DC, USA. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/404391467995897521/pdf/101642-WP-Box393261B-PUBLIC-2004-12-01-JDW-Disability-Building-Alliances.pdf Accessed 5 February 2019.

- World Health Organization, 2011. World report on disability. WHO library cataloguing-in-publication data. https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf Accessed 5 February 2019.

- Yeo, R & Moore, K, 2003. Including disabled people in poverty reduction work: “Nothing about us, without us”. World Development 31(3), 571–90. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00218-8