?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the relationship between health care expenditure and population aging in South Africa using yearly data from 1983 to 2015. Empirical evidence from an Autoregressive Distributed Lag approach to cointegration indicates that old dependency and life expectancy are major drivers of public health expenditure in South Africa besides the income. Particularly, when structural breaks are controlled for, income exhibits a long-term elasticity with respect to health spending greater than unity; suggesting that South African public health care has become a luxury good over time. Interestingly, South African public health spending is found to be responsive to demographic development only in the long run. This is consistent with the micro evidence that health expenditure increases with individual age with significant impacts in the long term. Finally, using economic and demographic projections statistics, we find that public health expenditure could roughly double in the next fifteen years ceteris paribus.

1. Introduction

Population aging is defined as an increasing median age in the population of a region due to decline in fertility rates and/or rising life expectancy (Mortimer & Green, Citation2015). In South Africa, fertility rate has dropped from 2.7 in 2001 to 2.3 in 2013 while the life expectancy has raised steadily from 53 years in 2001 to 60 years in 2014, hence approaching developed countries’ levels. The distribution of population by age features the increase in the share of older people (over 65 years) from 7.1% in 1996 to 8.0% in 2011. During the same period, the share of population aged between 0 and 14 years fell from 32.1% to 29.25%. Similar downward movement has been noticed for the population aged between 15 and 24 years. Therefore, though still much younger, South Africa is crossing the demographic distance from young and growing to old country (SSA, Citation2014). This trend is expected to continue as projections point to a number of roughly 7 million elderly persons in South Africa by 2030 compared to 4 million in 2011 (Statistics South Africa, Citation2016); making South Africa one of the few African countries experiencing a rapid increase in the number of people aged 60 and over. These statistics are consistent with the African projection that old-age cohort could account for 4.5% of the total population by 2030, and almost 10% of the total population by 2050 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) 2011, as cited in Nabalamba & Chikoko, Citation2011).

The impact of population ageing has become a fundamental concern for many developing countries. As individuals get older, their health status generally decreases, and this in turn results in an increase in the utilisation of health care services, and consequently health care expenditure. For many years, ageing was considered to be an issue that was encountered only in developed countries, however, it has progressively become a universal issue that is spreading through developing countries (Beard et al., Citation2011). In contrast to developed countries where the subject of population ageing has already taken shape, in developing countries, population ageing still remains relatively under-researched. There is a lack of specific policy initiatives targeted specifically the older population group.

Population ageing does not only have a consequence on health services and social needs, but also on health care spending. In developing countries, health care needs of older people generally depend on government for financing, and the medical care and equipment required by older people involves relatively expensive medical technology (Hashimoto & Tabata, Citation2010). Therefore, as the health care needs of the ageing population increases, the health care demands will also rise, and this impacts on a government’s health budget. This is particularly critical in South Africa, where as a result of poverty and the high unemployment rate, a significant share of the elderly population relies mainly on the government. The national government needs to implement interventions that will respond effectively to the arising challenges of population ageing, and the consequences thereof on health spending (HSP) (Hashimoto & Tabata, Citation2010).

While the increase in old age dependency due to ageing populations exerts an upward pressure on health care spending, most regions of South Africa still experience weak health care systems and other socio-economic conditions that considerably undermine the government’s ability to address these developing health care demands. Nabalamba & Chikoko (Citation2011) advocate low socio-economic indicators as one of the challenges in curbing the negative consequences of demographic transition. As a result of weak socio-economic environment combined with poor quality in medical care system, there is an increase vulnerability to poor health in old age (Maharaj, Citation2013), which in turn triggers the dependency of the elderly to government. This is different from advanced economies scenarios where an important share of the population has medical aids to support their medical expenses besides the generous social security system.

The South African health budget remains under pressure as expenditure on public hospitals is still not a priorityFootnote1 and remains a challenge. In addition, in policy dialogues, the impact of population ageing is not sufficiently visible, and therefore tends to be deprioritised in terms of funding and/or resources allocation, thereby increasing the vulnerability and marginalisation of older people (Lopreite & Mauro, Citation2017). This triggers their poor health status and therefore the government ability to not only respond to high health care demand given the free health care policy, but also to maintain old age contributions (Maharaj, Citation2013). In fact, the rise in expenditure barely keeps pace with demographic development and this raises concerns about the sustainability of old age support. Considering the rapid pace at which South African population is aging, coupled with significant socioeconomic challenges, understanding how health spending responds to the shift in the health profile of the population due to longevity remains imperative for health care provision and resource allocation.

Against this background, the study sets to quantify the response of health expenditure to the changes in population structure in South Africa; the main assumption being that a rise in the elderly cohort requires additional resources to respond to the increase in health care demand. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such attempt for South Africa as the empirical literature on the health care cost of population aging is mainly driven by evidence from developed and non-African contexts. Thus, unlike previous studies whose inference cannot be generalised to the African context, this paper expands the health care forecasting literature to South Africa.

Furthermore, besides its very different position in terms of economic development, South Africa is characterised by a relatively improved health system compared to other African countries. With the political transition, several social measures have been adopted in order to reduce significant inequalities due to apartheid. These include child grant, old age grant and free health care. With the ongoing demographic development and the related increase in health care demand, it is therefore imperative to investigate the fiscal cost of changes in population age structures. Specifically, understanding the health care implications of population aging can help design an adequate health policy in response to the demographic transition while providing significant insights for government budget forecasting.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows; Section 2 presents the literature review, Section 3 describes the methodology; Section 4 discusses the data and the results while Section 5 provides concluding remarks.

2. Literature review

Defined as a rising median age of the population due to decline in fertility rates and/or increasing life expectancy, population aging presents a critical challenge for many developing countries. It affects the demographic structure and bears important socio-economic consequences, including the economic performance, labour market participation, taxation, family health, composition of household, and migration (Lopreite & Mauro, Citation2017). Health being a critical development asset, it is generally believed that the improvement of economic performance entails healthy individuals to sustain the labour market requirements, government finance and other economic activities which, in turn, help them finance their health needs. However, individuals’ health profile depends on their life cycle as health care demand and thus health expenditures increase with age. And since the contribution to economic activities drops as individuals get old, a constant adjustment of the health care system to demographic changes remains a challenge. The literature provides two main hypotheses to inform such adjustment, namely the Red Herring and the Steepening Hypotheses which endeavour to identify the main demographic manifestations that drive heath care spending.

2.1. Red Herring Hypothesis

Formulated by Zweifel et al. (Citation1999), the Red Herring Hypothesis suggests that health care expenditure depends on the remaining last years of an individual’s life and not on their calendar age. The Red Herring Hypothesis is based on three important measurements: age; time to death; and individual health care expenditure (Gregersen, Citation2013). The Red Herring Hypothesis has been criticised by many researchers due to several methodological problems. These include Zweifel et al. (Citation1999), Zweifel et al. (Citation2004), Zweifel et al. (Citation2007), Colombier & Weber (Citation2009), Dormont et al. (Citation2006), Gregersen & Godager (Citation2013); Felder et al. (Citation2000); Karlsson & Klohn (Citation2014) among others.

Colombier & Weber (Citation2009) provide contrasting views to those held by Zweifel et al. (Citation2004) and Zweifel et al. (Citation2007) asserting that time to death is insignificant. For Colombier & Weber (Citation2009), population aging remains the most important age-related cost driver. In addition, morbidity also plays a more important role than mortality, but population aging remains the most influential age-related determinant. Dormont et al. (Citation2006) confirm Colombier & Weber’s (Citation2009) findings; highlighting that morbidity is an important determinant while the impact of ageing has a small effect on health care expenditure. But changes in morbidity is by far the more important driver in the increase in health expenditure.

Similarly, Felder et al. (Citation2000) analyse the demand for health care expenditure in the last 2 years of life from a model that accounts for age, mortality risk, and wealth and conclude that health care expenditure of people in their last years of life displays an increasing trend near death. This conclusion is further emphasised by Zweifel et al. (Citation1999), and substantiated by additional findings that the cost of dying is higher for the youth than for the old-age. For individuals who have retired, health care expenditure declines with age, and for low earning individuals (in comparison to high earning individuals), health care expenditure is much lower in their last days of life (Felder et al., Citation2000).

Gregersen & Godager (Citation2013) test the Red Herring Hypothesis using data received from an in-patient registry for hospital expenditures in Norway from the years 1998–2009. The results show that both age and mortality are two important factors influencing health care expenditure. Hospital records reveal that 9.2% of the expenditure was used in individuals in their last calendar years of life, suggesting that mortality-related expenditure is evident in the final days of an individual’s life. The results clearly support that mortality is, all other things being equal, associated with higher hospital expenditure (Gregersen & Godager, Citation2013).

2.2. Steepening Hypothesis

On the other hand, the Steepening Hypothesis states that ‘if health expenditure for the elderly grows faster than it does for younger people, the expenditure profiles become steeper’ (Buchner & Wasem, Citation2006). Thus, steepening is basically an increase in the proportion of health expenditure for old-aged (65 and over) divided by the younger (64 and below) age group (Gregersen, Citation2013). Rather than analysing the effect of age and time to death on individual health expenditure, the Steepening Hypothesis explores the age and time profiles of per capita health care expenditure. Gregersen (Citation2013) tests for the Steepening Hypothesis in the absence of mortality and report an evidence of steepening across cohorts with the exception of the 0-year-old group. However, when all age groups are considered, per capita health expenditure exhibits no linear function with age; implying no evidence of steepening. Moreover, Gregersen (Citation2013) observes that accounting for mortalities reduces the effect of steepening; possibly suggesting that part of the steepening effect is driven by increased mortality-related expenditures over time.

Felder & Werblow (Citation2008) investigate whether the age profile of health care expenditure really steepens over time. In contrast to the Steepening Hypothesis, Felder & Werblow (Citation2008) find no evidence for relevant steepening effects on age profiles for neither group, nor the components of health care expenditure over time. This implies no evidence of longevity on health care costs.

2.3. Longevity

One implication of the Red Herring and Steepening hypotheses is that longevity (generally proxied by aging and life expectancy) is a potential driver of health care spending. Life Expectancy among the elderly seems to have increased in most developed countries, and there is evidence that the health of the elderly has also improved over the years (Lopreite & Mauro, Citation2017). According to Shang & Goldman (Citation2007), the increase in longevity is the result of new developments in health care including better diet and consumption of high quality food, decreased environmental hazards, and access to better sanitation. Additionally, medical technologies have also played an important role in improving longevity, because any advances in medical technology will result in an improved health care system. Thus, longevity is one of the significant drivers of health expenditure.

Breyer et al. (Citation2010) study the effect of ageing on health care, and particularly health expenditure in various Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Their findings are consistent with the theory that there are noticeable health improvements because of a better diet and consuming high quality food; resulting to expansion in life expectancy. This is due to the fact that the improvement of per capita income growth boosts people’s willingness and ability to demand and pay for health services, which in turn, expand their longevity (Breyer et al., Citation2010).

Conducted recent study by Lopreite & Mauro (Citation2017) indicates that per capita health care expenditure responds more to ageing index than to per capita GDP and life expectancy in the short term. The authors conclude that any development in longevity tends to increase the lifetime health care expenditure per person; suggesting that health care expenditure increases with age and/or life expectancy. This leads to the conjecture that demographic changes are an important predictor of health expenditure in countries with relatively high life expectancy like South Africa.

2.4. Health care and demographics in South Africa

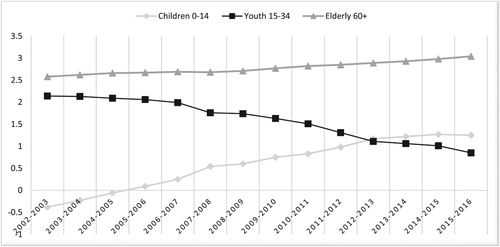

According to Statistics South Africa (Citation2017), between 2002 and 2016, fertility has declined from an average of 2.65 children per woman to 2.43 children; while life expectancy at birth without HIV/AIDS has increased from 61.2 to 65.2 for males and from 69.1 to 72.3 for females. The expansion of health programmes to prevent mother-to-child transmission and to improve access to antiretroviral treatment (ART) has significantly contributed to the improvement in life expectancy. Similarly, as a result of improved standard of living, healthier nutrition, better medical care and access to public health care services, mortality due to communicable disease such as HIV and Tuberculosis Bacterium (TB) has declined; leading the focus to non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, etc., particularly among those aged 65 and older. As a result, historical demographic estimates point to an increasing trend in the proportion of elderly in South Africa from 2.58% in 2002/2003 to 3.4% in 2015/2016 coupled with a declining trend in the working age cohort (see ). This suggests new financial demands that the South African government is bound to face.

Prior to 1994, the distribution of health care service and health policies appeared to favour well-off individuals, even though most of the problems associated with illness was greater for low-income groups. Access and delivering appropriate service to the needy was a major challenge (Coovadia et al., Citation2009). However, after 1994, interventions and policies were introduced with the aim of addressing the inadequacies in the South African health system, and also to transform the health sector to a functional health system accessible to everyone. According to Alli & Maharaj (Citation2013), the older population is among the poorest in every developing country. The old-age cohort has the lowest levels of income, the poor education background, and most of all the limited access to labour, pensions, or other benefits. These conditions result in an increase in old-age dependency on the working class or the government. While public health sector suffers from poor management, under-funding and deteriorating infrastructure, an important share of the population relies on government for health care services. On average, South Africa spends approximately 8.5% of GDP on health care. Unlike private health care accessible to a limited share of the population, public health services in South Africa are financed entirely out of the tax revenue and serve about 84% of the population, particularly those considered the most vulnerable and living under harsh socio-economic and health conditions.

In response to the challenges faced by the health care sector, the government has proposed a number of policies to correct the observed imbalances (Rispeli, Citation2016). The White Paper and the National Development Plan (NDP) has set extensive goals such as providing affordable access to quality health care while promoting health and well-being. In addition, specific directions have also been introduced, such as phasing in National Health Insurance (NHI) with the focus of improving public health facilities (Rispeli, Citation2016). However, the implementation of these policies has not been successful to turn around the overall performance of the health sector, as many individuals in underprivileged areas still find it difficult to access even the most basic health care.

On the other hand, there have been a number of successful stories in the health sector. The most important one has been the response to HIV, which has been instrumental in improving the key health indicators relating to death rates, life expectancy, and maternal, child, and infant mortality. Significant progress has been made in medicine procurement, which has resulted in significant savings (Blecher et al., Citation2017). The NHI system also has the potential to improve efficiencies in the overall health system, through the following: improved pooling; strategic purchasing; medicine price reductions through central procurement; redistribution; improved quality in the public sector; and providing greater access to general practitioners (Blecher et al., Citation2017). However, these improvement strategies require further assessment in order to identify not only the success factors but most importantly possible constraints to their implementation. Given that financial constraints have often been cited as a major impediment to the improvement of the health system in developing countries, this study examines the role of longevity in predicting South African health care spending. This complements the existing literature that mainly emphasises the role of mortality and morbidity in driving health expenditure around the world. To this end, an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach to cointegration is employed to test the existence of a long-term relationship between public health spending and changes in population structure while controlling for the level of economic development.

3. The ARDL methodology

The ARDL co-integration approach was developed by Pesaran & Shin (Citation1999) and Pesaran, Shin, & Smith (Citation2001) and is widely implemented in the analysis of long-term relationships if the data generating process is believed to follow a stochastic process that are integrated of order zero and one (that is I(0) and I(1)). In fact, since not all time series are non-stationary, the use of traditional co-integration techniques is invalid in the presence of stationary variables as it requires all the variables to be non-stationary at levels (Peasaran & Shin, Citation1997). Unlike traditional cointegration approaches (Johansen's, Citation1991, Citation1995; Engle & Granger, Citation1987) Pesaran & Shin (Citation1999) showed that ARDL method of cointegration has the advantage of facilitating the analysis of long-term relationships when the underlying variables are either I(0) or I(1).Footnote2 Moreover, this approach does not impose similar lag length for all variables included in the model; Therefore, improving the flexibility in the choice of lag length across variables. Because of its tractability in terms of stationarity prerequisite, the ARDL model has been used in econometrics for decades, and has recently gained popularity as a method of examining long-run and co-integrating relationships between variables (Pesaran & Shin, Citation1999). Considering that health spending (HSP) is explained by both economic and demographic factors, the ARDL model hypothesis tests the presence of a long-term relationship between HSP and the vector of explanatory variables, including life expectancy (LE), old age dependency ratio (OADR), and output (GDP).

More specifically, the empirical log–log representation is formulated as follows:(1)

(1) where t is the deterministic drift, HSP, LE, OADR, and GDP are, respectively, per capita real health expenditure, life expectancy, old age dependency ratio and per capita real GDP all in their natural logarithm forms. εt is the error term assumed to be normally distributed.

, i = 1,2,3 which are theoretically expected to be positive, represent life expectancy, old age dependency ratio and income elasticities of health expenditure, respectively.

Equation (2) below provides the associated ARDL form which allows Equation (1) to be estimated using the ordinary least squared (OLS) technique.(2)

(2) with

being the difference operator.

In the presence of cointegration, the long-term effect can be estimated by converting the model into long-term representations, showing the long-term response of the dependent variable to a change in the explanatory variables (Pesaran et al., Citation2001). This is known as the unrestricted error correction model (ECM) with the following specification:(3)

(3) where ECT is the estimated residuals from Equation (2) and its coefficient (

) measure the speed of adjustment towards the equilibrium referred to as long-term relationship. The existence of such a relationship is assessed using the bounds test. This is simply a test of the null hypothesis that βi = 0 against the alternative that βi ≠ 0, which is based on a non-standard F-test proposed by Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) and refined by Narayan (Citation2005) to accommodate small samples.

While short-term coefficients are given by α’s, δ’s, θ’s and ϕ’s, long-term-term coefficients (on the other hand are computed as follows:

(4)

(4)

The standard error of these long-term coefficients can be calculated from the standard errors of the original regression using the delta method. Further details on ARDL procedure can be found in Sbia et al. (Citation2014).

4. Data and empirical results

The study uses annual time series data of OADR, LE, GDP, and HSP from 1983 to 2015 subject to the availability of data. The data come from two different sources, the National Treasury database and the Federal Reserve of St Louis database.

According to Statistics South Africa (Citation2014) ‘old-age dependency is a single measure of the ratio of the elderly, non-working, and pensionable population aged 65 and older relative to the working population aged 15–64 years of age’. The OADR provides an indication of ageing in a population, since population ageing generally involves an increase in the number of elderly people and occurs concurrently to a decrease in the number of younger population. On the other hand, LE is also one of the most frequently used health status indicators. LE at birth is defined by OECD (Citation2017) ‘as how long on average a new born can expect to live, if current death rates do not change’. It is assumed that mortality declines because of an improved standard of living; leading to longevity. This means that decline in mortality implies a higher life expectancy in old age, which results in population aging from the top of the population age structure.

The study also controls for the standard of living using per capita real GDP. Finally, HSP is measured by the per capita expenditure on health care goods and services. Although HSP is usually financed via a mix of financing arrangements, the paper focuses on public health expenditure given the government mandate to provide free health care and social supports to the vulnerable population including the elderly group.

Finally, the study makes use of economic and demographic projection to forecast the per capita health expenditure in the horizon 2030. The projections statistics are obtained from the International Futures (IFs) maintained by the Pardee Center at the University of Denver.Footnote3

The first panel of provides the summary statistics of the time series used in the cointegration analysis, namely, HSP, GDP, LE and OADR. It appears that all the variables display an increasing trend during the sample period despites the existence of selected years of structural breaks identified in the second panel. In addition, with the exception of HSP, the Jarque-Bera normality test results fail to reject the null hypothesis of normality; hence substantiating the use of a normal distribution based analytical tool for the empirical investigation.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

In order to ensure that none of the series analysed is I(2), the unit root test is performed with and without structural breaks; the overreaching conclusion that all the variables are either I(0) or I(1) validating the use of ARDL cointegration approach. While both types of unit root tests reach consistent results,Footnote4 structural breaks based unit root test has identified selected dates during the sample period, which are worth noting as long as health and demographic trends are concerned in South Africa. These include 1990, 2010, 2014 and 2015.

Structural breaks occurred in the South African health spending in 1990 and 2010. Besides the political transition started in 1990, the 1990 millennium development goals emphasised the health and health systems with possible effect on the health spending in South Africa. This is followed by a five-year cooperation agreement funded by the US agency for international development. This health policy project introduced in 2010 is thought to have boasted public expenditures on health care good and services. Similarly, the hosting of the 2010 FIFA World Cup is likely to have rebranded the South African economy and contributed to the growth of tourism and foreign direct investment with positive externalities on the GDP. This is confirmed by the structural break in the real per capita GDP in 2010.

On the other hand, the demographic variables display the presence of structural breaks in 2015. While the 2010s is characterised by the recovery from the 1990s decline in LE, 2015 points to the high pace of population aging; the maximum OADR occurring in 2015 over the sample period. In effect, the beginning of a new democracy in 1994 brought positivity regarding the future of the country, and the new administration had to redesign every level of government in the context of a fractured governance system. South Africa introduced free Antiretroviral (ARV) for the treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in 1998. However, the roll out of ARV’s only started in April, 2004 after a lengthy battle between activists and the ruling government who questioned the link between HIV and AIDS, and ARV’s effectiveness. Today South Africa has the biggest programme in the world and people are able to receive the lifesaving treatment leading to an increase in life expectancy (The South African Health News Service, Citation2014). reports the ARDL long-term coefficients since the bound test rejects the null hypothesis of no cointegration at the conventional level of significance (5%). These results are obtained from an unrestricted intercept ARDL (1,1,1,1) model selected automatically based on the BIC information criteria. Not only the restricted constant is negative and strongly significant () but the estimated coefficients are all significant and of expected signs. The coefficients of GDP, LE and OADR are positive suggesting a positive elasticity of income, life expectancy and old dependency with respect to the public health expenditure.

Table 2. Long-term ARDL cointegration model (1,1,1,1).

Table 3. The ARDL cointegrating short-run error–correction model (1, 1, 1,1).

In the first scenario where structural breaks are not accounted for, it is found that 1percent increase in GDP leads to 0.9920% increase in health spending. However, the result of Wald test indicates that this income elasticity of public health spending is not statistically different from unity confirming that over time, public health care in South Africa has been a normal good with unitary income elasticity. This is different from the US where health care has become a necessity good across time (Murthy & Okunade, Citation2016). According to these authors, basic health needs are fulfilled as wealth level increases; hence justifying the relative less effect of income growth on health care cost. This theoretical argument was formulated by Zhang (Citation2013) and confirmed by Acemoglu et al. (Citation2013). Unlike these authors who focus on the total health expenditure in an advanced economy, it is worth stressing that as income increases, basic health needs are far from being satisfied for the majority of the South African population given the high and persistent level of unemployment. Moreover, as population ages, the deterioration of the health status of retirees who never worked trigger the demand of public health care so that the proportion of per capita health spending remains the same as the national income increases. On the other hand, the demographic coefficients denoting the elasticities of public health spending with respect to life expectancy and old age dependency ratio are respectively 2.4512 and 2.0734; indicating that longevity is a significant driver of the health care cost in South Africa.

The second scenario indicates the relevance of controlling for structural breaks as substantiated by the statistical significance of the dummies’ coefficients. Two dummies are included in the analysis that capture the political transition and the effectiveness of the ARVs. Controlling for these structural breaks leads to slightly different results as the long-term income elasticity under this scenario is found to be greater than unity; suggesting that public health care has become a luxury good across time. This is reflective of the meagre health care system characteristic of developing countries. Namely, per capita health spending increases by 1.67% following a 1% increase in per capita GDP. Differently from the first scenario, the demographic elasticities are respectively 1.52 and 1.32 for LE and OADR; suggesting a relatively smaller response of health spending to demographic variables than to per capita income. However, these findings remain consistent with the aging literature that emphasises the rises of health spending during the old age, and namely during the life ending time.

In line with the representation theorem that each cointegrating relationship is associated with an error correction model (ECM), reports the estimated short-term elasticities from the ARDL(1,1,1,1)- ECM. The coefficients of ΔGDP, ΔLE and ΔOADR are all positive and significant in the absence of structural breaks whereas income tends to be the only short-run driver of health spending in the presence of structural breaks; demographic factors playing no significant role in the short term. Interestingly, the short-term income elasticity is less than one; indicating that in the short-run health care is a necessity good. In addition, the ECT term is highly significant and of negative sign as expected; hence approving the existence of the ARDL cointegration relationship between health spending, economic and demographic factors. Furthermore, the ECT coefficient of −0.7553 and −0.9052 without and with structural breaks, respectively suggests that roughly 76%, respectively, 91% correction to the disequilibrium in the government health spending due to past shocks take place in the current period. The relatively high speed of adjustment of public health expenditure in South Africa contrasts Murthy & Okunade (Citation2016) who report an estimated correction of 27% for the US health expenditure via the economic and demographic factors. According to these authors, the low speed is attributed to the complexity and rigidity of the health care sector; implying that South African public health care sector is relatively more flexible.

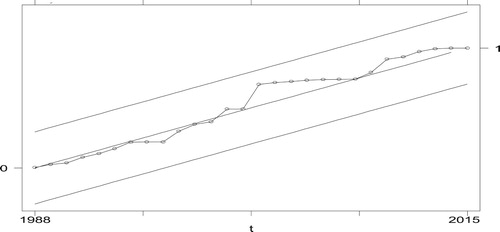

From the robustness perspective, empirical results display sufficient evidence to support the ARDL (1,1,1,1) specification automatically selected by the BIC under both scenarios. Particularly, the Ramsey test of misspecification fails to reject the null hypothesis of no misspecification while the Breusch–Pagan test of heteroscedasticity validates the homokedasticity assumption. In addition, the absence of serial correlation could not be rejected given the high p-value of the Breusch–Godfrey test of serial correlation. Finally, the normality assumption of the ARDL procedure holds as the test of normality fails to reject the null hypothesis of normal distribution. Furthermore, as it is standard with autoregressive models, the CUSUM test is performed to check the stability of the coefficient. displays a CUSUMFootnote5 squared that lies inside the 95% critical boundary; confirming that the estimated parameters of the ARDL (1,1,1,1) model are indeed stable.

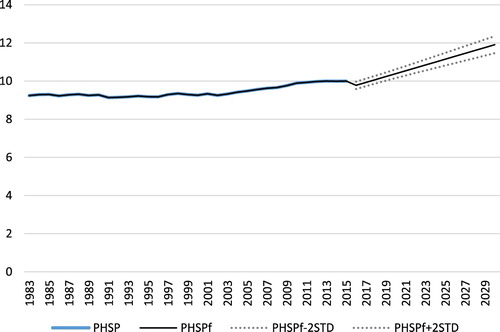

Therefore, the estimated model is ready to be used for forecasting purpose. As mentioned earlier, the study uses the projection data on economic performance and demographic trends to forecast public health expenditure in the 2030 horizon. Forecasting output indicates that public health expenditure could double in the next 15 years under both scenarios; that is, an average growth rate of about 6.216% and 5.685% every year in the absence and presence of structural breaks, respectively. provides the 2-standard deviation forecast graph for the structural break scenario.

Overall, our findings show that demographics and income are major drivers of health spending in the public sector; confirming our earlier conjecture that longevity is an important predictor of health care spending in South Africa. However, this inference relies on a relatively small sample size which eventually requires some degree of caution as the presumed asymptotic properties of the estimates might not necessary be met. Moreover, possible complementary and/or substitution effects across different health care categories could not be controlled for given the lack of disaggregated health spending data by age group. In such conditions, the intensity of the estimated effect remains indicative though still informative.

5. Concluding remarks and policy implementations

This paper is the first study to empirically analyse the health care cost of population aging in South Africa using the ARDL approach to cointegration. By extending the cross-sectional literature on demographics and health spending to time series models, we show that old dependency represents a major driver of public health expenditure in South Africa besides the income. Furthermore, the empirical set up allows us to identify selected periods of structural breaks experienced by all variables understudy. When these structural breaks are controlled for, our ARDL model exhibits a long-term relationship among public health expenditure, income, life expectancy and old age dependency ratio. Furthermore, the forecasting analysis is performed based on economic and demographic projections statistics in the horizon 2030 since the estimated model passes all the diagnostic tests. Particularly, we find that public health expenditure could roughly double in the next fifteen years if everything else remains constant.

In comparison with the literature in developed countries, empirical results indicate that South African public health care remains a normal or a luxury good in the long run. This is different from the US where health expenditure has moved from a luxury good (income elasticity of health expenditure greater than one) as in Okunade and Murthy (Citation2002) to become a necessity good (income elasticity of health expenditure less than one) as in Murthy & Okunade (Citation2016). However, in the short term, health care seems to be a necessity in South Africa as vindicated an income elasticity of health expenditure less than unity.

In addition to being a normal/luxury good, South African public health spending appears to be more responsive to demographic development in the long run. This contrasts Murthy & Okunade (Citation2009) who indicated that age has no impact on health expenditure in the African context and these results are consistent with the micro evidence that health expenses increase with individual's age; bearing significant impacts in the long term.

From the policy perspectives, our findings point to the need to redesign the health system through an intensive promotion of quality health care from public sector to accommodate the increasing and unavoidable growth in the elderly population group. For instance, preventive health care through educational programmes that encourage healthy lifestyles and impart knowledge to the elderly about healthy living could be an efficient strategy to contain elderly health care budget. Alternatively, government might review retirement plans to ensure self-maintenance of pensioners. If individuals live longer, they could probably work longer, and thus increase their lifetime income, which, in turn will reduce their dependency on public funding. This might also channel through budget allocation by making provision for longevity and related issues although this is not without consequences on other spending categories. One such provision is the public subsidy for health insurance coverage, which can represent an important finding instrument for population in their retired age. Due to weak macro-economic conditions in the country and other fiscal pressures on government, the health expenditure budget remains constrained. South Africa’s GDP is unlikely to grow much more than 3% a year as noted in the subdued projections and the government has stated its intentions to decrease the size of its deficit relative the GDP through measures to increase revenue and control for growth in expenditure. Given these limitations, health sector will have to compete for budget increase with other services for which there is great backlog. This suggests that the response of the government health budget to demographic changes is likely to come from other sources of finance; the national health insurance being a potential alternative. As a pathway towards the universal health coverage, the effectiveness of the national health insurance can be seen as a mitigating policy in addressing the projected increase in health spending.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 According to the National Treasury (Citation2017), public health care expenditure has been stagnant (between 2013/14 and 2014/15) relatively to other public sector services.

2 This is the case in the present study. As can be seen in the empirical result chapter, the variables under consideration in the study are either I(0) or I(1); hence fulfilling the implementation of ARDL.

3 http://www.ifs.du.edu/ifs/frm_CountryProfile.aspx?Country=ZA. To build its forecasts, IFs accounts for the complex dynamic of human development and its connection with other development systems by relying on many variables and connections with a wide range of development network including: agriculture, economy, education, energy, environment, socio-political, health, infrastructure, international politics and population. This Center compiles data for 186 countries and details on the projection methodology are available from https://pardee.du.edu/understand-interconnected-world.

4 OADR series is the only exception where the standard unit root test fails to detect the presence of unit root due to the existence of structural breaks. Particularly, OARD is I(1) rather than I(0) as suggested ADF and KPSS unit root test results.

5 The reported Figure is based on the first scenario output. However, similar picture is obtained with the inclusion of dummies; hence the decision not to replicate the figure.

References

- Acemoglu, D, Finkelstein, A & Notowidigdo, M, 2013. Income and health spending: evidence from oil price shocks. The Review of Economics and Statistics 95, 1079–1095.

- Alli, F & Maharaj, P, 2013. The health situation of older people in Africa. In Maharaj, P (Ed.), Aging and health in Africa (pp. 53–89). Springer Science and Business Media, New York.

- Beard, J, Kalache, A, Delgado, M & Hill, T, 2011. Ageing and urbanization. In Beard, JR, Biggs, S, Bloom, DE, Fried, LP, Hogan, P, Kalache, A & Olshansky, SJ (Eds.), Global population ageing: Peril or promise. World Economic Forum, Geneva.

- Blecher, M, Kollipara, A, Mansvelder, A, Daven, J, Maharaj, Y & Gaarenkwe, O, 2017. Health spending at a time of low economic growth and fiscal constraints in South African health review. In: Padarath A, Barron P, editors. Retrieved from health system Trust: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/south-african-health-review-2017.

- Breyer, F, Costa-Font, J & Felder, S, 2010. Ageing, health, and health care. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 26(4), 674–690. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grq032

- Buchner, F & Wasem, J, 2006. Steeping of health expenditure profiles. The International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics 31, 581–599.

- Colombier, C & Weber, W, 2009. Projecting health-care expenditure for Switzerland: further evidence against the “red herring” hypothesis. International Journal of Health-Planning and Management 26(3), 246–263.

- Coovadia, H, Jewkes, R, Barron, P, Sanders, D & McIntyre, D, 2009. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. The Lancet 374, 817–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60951-X

- Dormont, B, Grignon, M & Huber, H, 2006. Health expenditure growth: Reassessing the threat of ageing. Health Economics 15(9), 947–963. doi: 10.1002/hec.1165

- Engle, RF & Granger, CWJ, 1987. Co-integration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica 55(2), 251–276.

- Felder, S & Werblow, A, 2008. Does the age profile of health care expenditure really steepen over time? New evidence from Swiss cantons. The International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics 33, 710–727.

- Felder, S, Meier, M & Schmitt, H, 2000. Health care expenditure in the last six months of life. Journal of Health Economics 19, 679–695. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(00)00039-4

- Gregersen, FA & Godager, G, 2013. Hospital expenditure and the red herring hypothesis: Evidence from a complete national registry. Health Economics Research Programme at the University of Oslo, Oslo.

- Gregersen, FA, 2013. The impact of ageing on health care expenditures: a study of steepening. The European Journal of Health Economics 15, 979–989. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0541-9

- Hashimoto, K & Tabata, K, 2010. Population aging, health care and growth. Journal of Population Economics 23, 571–593. doi: 10.1007/s00148-008-0216-5

- Johansen, S. 1991. Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica 59, 1551–1580.

- Johansen, S. 1995. Likelihood-based inference in cointegrated vector autoregressive models. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Karlsson, M & Klohn, F, 2014. Testing the red herring hypothesis on an aggregated level: ageing,time-to-death and care costs for older people in Sweden. The European Journal of Health Economics 15(5), 533–551.

- Lopreite, M & Mauro, M, 2017. The effects of population ageing on health care expenditure: A Bayesian VAR analysis using data from Italy. Health Policy 121(6), 663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.03.015

- Maharaj, P, 2013. Aging and health in Africa. Springer Science, New York.

- Mortimer, J & Green, M, 2015. Briefing: the health and care of older people in England 2015. London: Age UK. www.ageuk.org.uk/professional-resources-home/research/reports/care-andsupport/the-health-and-care-of-older-people-in-england-2015/. Accessed 13 June 2019.

- Murthy, VNR & Okunade, A, 2009. The core determinants of health expenditure in the African context: Some econometric evidence for policy. Health Policy 91(1), 57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.10.001

- Murthy, VNR & Okunade, AA, 2016. The determinants of US health expenditure: Evidence from autoregressive distributed lad (ARDL) approach to cointegration. Economic Modelling 59, 67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2016.07.001

- Nabalamba, A & Chikoko, M, 2011. Aging population challenges in Africa. Africa Development Bank 1(1), 1–19.

- Narayan, PK, 2005, The saving and investment nexus for China: evidence from cointegration tests. Applied Economics 37, 1979-1990.

- National Treasury, 2017. Medium term expenditure framework – chapter 5, consolidated spending plans. National Treasury, Pretoria.

- Nkoro, E & Uko, AK, 2016. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique: application and interpretation. Journal of Statistics and Econometric Methods 5(4), 63–91.

- OECD, 2017. OECD health indicators. Retrieved from OECD: http://www.oecd.org/healthstat/life-expectancy-at-birth.htm.

- Okunade, AA & Murthy, VNR, 2002. Technology as a “major driver” of health care cost: a cointegration analysis of the Newhouse conjecture. Journal of Health Economics 21, 147–159.

- Peasaran, MH & Shin, Y, 1997. An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Department of Applied Economis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

- Pesaran, MH & Shin, Y, 1999. An autoregressive distributed lad modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Chapter 11 in Strom (ed.), Econometrics and economic theory in the 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial symposium (Discussion paper). Cambridge University Press.

- Pesaran, MH, Shin, Y & Smith, RJ, 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16, 289–326. doi: 10.1002/jae.616

- Rispeli, L, 2016. Analysing the progress and fault lines of health sector transformation in South Africa in the “South African Health Review”. Retrieved from Health Systems Trust: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/south-african-health-review-2016.

- Sbia, R, Shahbaz, M & Hamdi, H, 2014. A contribution of foreign direct investment, clean energy, trade openness, carbon emissions and economic growth to energy demand in UAE. Economic Modelling 36, 191-197.

- Shang, B & Goldman, D, 2007. Does age or life expectancy better predict health care expenditures? Health Economics 17(4), 487–501.

- Statistics South Africa, 2014. Census 2011: Profile of older persons in South Africa. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Statistics South Africa, 2016. Mid-year population estimates. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Statistics South Africa, 2017. Mid-year population estimates. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- The South African Health News Service, (2014). South Africa celebrates 10 years of free HIV treatment. Retrieved from Health E-News: https://www.health-e.org.za/2014/04/04/south-africa-celebrates-ten-years-free-hiv-treatment/.

- Zhang, L, 2013. Income growth and technology advance: The evolution of the income elasticity of health expenditure. Working Paper. University of Oslo, 1–42.

- Zweifel, P, Felder, S & Werblow, A, 2004. Population ageing and health care expenditure: New evidence on the “red herring”. Health Economics 29(4), 652–666.

- Zweifel, P, Felder, S & Werblow, A, 2007. Population ageing and health care expenditure: a school of ‘red herrings’? Health Economics 16(10), 1109–26. doi: 10.1002/hec.1213

- Zweifel, P, Felder, S & Meiers, M, 1999. Ageing of population and health care expenditure: A red herring. Health Economics 8(6), 485–496. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199909)8:6<485::AID-HEC461>3.0.CO;2-4