ABSTRACT

The Guide to the National Water Act, 1998 (Act 36 of 1998) regards the availability of water as a basic human right. However, local governments seem to struggle to pay for the water they provide to their residents as prescribed in the Water Services Act, 1997 (Act 108 of 1997). This study focused on the domestic provision and consumption of water in Soweto, one of the largest townships in the Johannesburg area of South Africa. Surveys were conducted with 372 respondents from three different socio-economic suburbs in Soweto with the aim to establish their water use perceptions and practices. Study results indicate implementation of the National Water Act is still being resisted by Sowetan households more than two decades after its adoption, due to the difference in expectations of the municipality and the residents regarding rights to water access and responsible usage.

1. Introduction

South Africa is a semi-arid country that requires deliberate efforts from all water users to manage the demand and the usage of this resource, especially in view of climate changes that are predicted to impact negatively on the future availability of water in this region. The reform of the previous water management law needed to be judicious in order to regulate the supply of and the demand for this resource for sustainability reasons, considering the aridity status of the country. This judicious management of the resources was articulated in the White Paper on National Water (Department of Water Affairs and Forestry [DWAF] Citation1997) and the National Water Act, 1998 (Act 36 of 1998) (NWA) (DWAF Citation1998; Karodia & Weston Citation2001). These two documents seek to ensure long-term water security and to mitigate possible negative consequences of mismanagement on the growth of the economy (Mathipa & Le Roux Citation2009).

Water shortages are no longer only possible future events, they are a reality now as well. There are now many parts of South Africa where citizens have been forced to save water through water shedding. Many areas in South Africa have had to go without water for days. Thus, the call to treat water as a scarce resource is a reality (Blignaut & Van Heerden Citation2009). According to Muller et al. (Citation2009), a water secured position can only be attained when the social and productive potential of the resource has been sufficiently harnessed to benefit society and its economic activities.

Increasing pressure to deal with the challenges of economic growth and social demand in water-stressed countries puts pressure on the water sector (Muller et al. Citation2009; Van Vuuren Citation2009). Solomons (Citation2013) observes that although South Africa is a water-stressed country, its economic growth pathway has become water intensive. Rapid population growth in South Africa also exerts pressure on the environment through the over usage of water and water pollution. This limited resource needs to be protected from pollution and conserved to achieve efficient usage. Considering that the pressure on the water sector outlined above, and the commitment of the government to the extension of basic water provision to every citizen, the judicious management of the resource has, therefore, become a matter of urgency.

South Africa is globally rated as the 30th driest country, (GreenCape Citation2017), experiencing low levels of rainfall, with high unpredictable and high levels of evaporation owing to its hot climate (Hoffman et al. Citation2009). Two-thirds of South Africa is semi-arid with a variable annual rainfall which is far less than the global average (Blight & Fourie Citation2005). Ziervogel et al. (Citation2014) concluded that South Africa’s developmental needs are threatening the ecosystem. The authors found that South Africa has the highest per capita emissions compared to other countries on the African continent although South Africa has developed adaptive responses that focus on reducing vulnerability to the risk of climate change, early climate risk warnings and water demand management. The main challenge, according to the authors, is the defective implementation of such adaptive responses. This is confirmed by Colvin et al. (Citation2016) who approximated that the demand for water in South Africa will reach 17.7 billion cubic metres in 2030. This has a direct impact on the available potable water for the country. The Department of Water Affairs of South Africa has pointed out that 10% of the water supply could come from desalination plants by 2030. Odendaal (Citation2013) cautioned that uncertain water security challenges, water quality and concomitant water management challenges could be a deterrent on South Africa’s socio-economic growth. Thus, there is a need for increased efficiency in handling the resource across all stakeholders by balancing supply with demand, in order to deal sustainably with the growing population and economy.

Donnenfeld et al. (Citation2018) has suggested that South Africa as a water scarce country needs to employ technologies that will assist in realigning supply and demand for the resource while ensuring water security for future generations. The threat of water shortages has already been experienced in the Western Cape, where available water is not sufficient to meet social needs (Muller Citation2017). Prior to the challenges of the Western Cape, the World Cup Legacy Report (Citation2011) mentioned that Johannesburg was likely to run short of water should the Water Services Act, 1997 (Act 108 of 1997) (WSA) fail to manage the demand. Authors such as Herrfahrdt-Pahle (Citation2010) and Donnenfeld et al. (Citation2018) advised that appropriate water governance in South Africa requires institutions to regulate the social and ecological interface to mitigate the challenges of water resource management. The competitive tensions between social and ecological systems must be managed effectively. According to the authors, the White Paper on National Water Policy (DWAF Citation1997) and the WSA provide suitable guidelines for management of these competitive tensions.

This article focuses on water usage patterns in selected poor communities instead of affluent communities because of socio economic differences and the usage of the resource. In the communities studied there are large numbers of households that live in poverty. The NWA states that basic water services must be provided to all South Africans free of charge, but if a household exceeds the free basic allocation of water, they must start paying for it. Affluent households are charged higher tariffs for inefficient usage of the resource. Poor households, on the other hand, are encouraged to stick to the basic provision of water. This approach is supposed to encourage wise usage of the resource and to avoid higher tariff charges.

2. Historical evolution of urban water policy in South Africa

Roux (Citation2002) explains that policy is developed after public officials and political office bearers become aware of deficiencies in society. The White Paper on National Water Policy was approved in 1997 (DWAF Citation1997). It contained guidelines on how water resources should be used and preserved. This was followed in 1998 by the NWA which replaced the Water Act, 1956 (Act 54 0f 1956) (WA) (DWAF Citation1956). The WA was a policy instrument developed to manage water in a specific way. It was the first comprehensive water management policy instrument in South Africa (Uys Citation1996). However, it was mainly concerned with the supply side of the resource. Water demand side issues, namely recognising water as an economic good that requires management of demand, were not adequately addressed within the framework of this Act. Pienaar & Van Der Schyff (Citation2007) concluded that the true status of water was vague and not clearly defined in the WA.

The WA was further designed within the ideological framework of apartheid and therefore did not treat black communities in the same way as white communities in South Africa. It was based on a consecutive stream of changing water allocation and management practices from the Dutch to the British then to the Afrikaners, who came into power first via the South African Party in 1910 and later via the National Party in 1948.

The main principle underlying the policy was the British common-law riparian rights system which allowed virtually exclusive water rights to individual white land owners to the exclusion of most black residents who could not own land individually in the 87% so-called white urban and rural areas of the country. In these areas they were only allowed to live in strictly demarcated and governed black ‘townships’ in cities and towns, if they complied with rigid requirements that included formal permission on the basis of fixed employment (Findley & Ogbou Citation2011). Blacks could only rent or were housed for free in government or employer-provided houses, apartments or rooms in sub-economic housing schemes. Basic rudimentary municipal electricity, water and sanitation services were provided either at a subsidised rate or for free to the occupants in those housing schemes (Tewari Citation2009). Bester (Citation2018) notes that after 30 years of consistent occupation, blacks could, theoretically, achieve individual title hold over their occupied properties. However, according to apartheid policy, blacks were regarded as temporary migrant workers in these areas and were compelled by law to return for short periods to their traditional ethnic ‘homelands’ like Transkei, Ciskei, Venda and Gazankulu which prevented them from obtaining individual freehold land titles in these urban areas outside of those ‘homelands’ (Reed Citation2013).

The election of the post-apartheid democratic government of South Africa in 1994 called for a change from the racially-based discrimination of the past to a non-racial and non-discriminatory philosophy and priorities in all areas of society (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa) (Republic of South Africa Citation1996). The NWA that replaced the WA included explicit corrective measures in terms of non-racial and non-discriminatory socio-economic rights for all citizens. Francis (Citation2005) noted that policy reform was a primary focus during the period of transition in order to counter apartheid policies which had left a legacy of inequality including in the provision of basic services such as access to water.

The Bill of Rights in the post-apartheid Constitution (Republic of South Africa Citation1996) states that the provision of these services are a way of improving the standards of living among poverty burdened citizens. This provision required that the state take reasonable legislative and other measures within its available resources to strive for the progressive realisation of human rights (Mathipa & Le Roux Citation2009). The NWA recognises that, due to scarcity challenges, both supply and demand management are important for a water-scarce country like South Africa (Karodia & Weston Citation2001). This calls for a deliberate effort among all the users of the resource in the country to collaborate and develop strategies to mitigate the increasing threat.

The new government immediately made determined efforts to deal with the environmental issues and the provision of basic needs for the black majority population who had formerly been side-lined. The NWA has the explicit objective of reversing the social imbalances inherent in Subsection 2(c) of the WA. Goldin (Citation2010) confirms that the NWA was transformational in this respect. Jaime-Castillo & Marques-Perales (Citation2014) state that attitudes towards redistributive policies are shaped by beliefs about inequality. Walker et al. (Citation2010) caution that sometimes policy makers choose to ignore uncertainties when making policies, relying on intuition instead. The magnitude of uncertainty can be so large that, in certain situations, a later revision of the policy is necessary. The main stakeholders in this specific objective of the NWA were the municipalities and their poor residents. Their relationship should be such that they should be able to jointly manage the demand for water, among other communal issues.

The most important implementation instruments used for transforming the water management sector are the NWA and the WSA which were designed to constitute the main legislative framework for water services and water resource management in post-apartheid South Africa (Smith Citation2009). The implementation agencies for the WSA are the local municipalities (DWAF Citation2005).

The domestic consumption of the resource has been growing at an alarming rate in South Africa, especially in the urban areas, mainly due to population growth and urban migration. Donnenfeld et al. (Citation2018) state that the municipal sector is the second largest user of the resource for residential use, with the agricultural sector being the largest. Municipal sector water withdrawals in 2015 were 27%, while the agricultural sector were 63%. Though there are other stakeholders in the water supply chain, the municipalities are the first point of contact with their communities.

In order for municipalities to comply with the WSA, they must be able to perform the two primary tasks of economic regulation and social regulation. The White Paper on Local Government (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs Citation1998) consolidates economic and social regulation in relation to services managed by municipalities as follows:

Ease of access to basic services;

Convenience of the services provided;

Affordable services; and

Timeous provision of services, suitable for a specified purpose and continuous provision.

South Africa has met the objective of the 2000 Millennium Development Goals of ensuring that by 2015 the number of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water is reduced (Filofac Citation2007). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) now require that countries should strive to ensure that everyone has access to safe and affordable drinking water by 2030 (United Nations Development Programme, SDG Citation2017). Statistics SA (Citation2017) reported that the percentage of people who have access to a source of drinking water improved from 84% to 86.6% in 2016. South Africa therefore still has some way to go to meet the current SDG goals regarding water for domestic use.

However, for each success there is frequently also a downside. The growing population is proving to be a challenge when it comes to water provision. Statistics SA (Citation2017) pointed out that the goals of water service provision for all by 2030 requires greater efficiency in usage and new wisdom in water planning and management. Stakeholders need to regard water as a fragile resource, without which the country cannot function. New evidence calls for adaptation to new methods of managing the resource in the country, where management becomes the responsibility of all those that live in it.

Knüppe & Meissner (Citation2016) suggested that collective responsibility will encourage national awareness of sustainable usage of the water resources which in turn would yield the needed results in relation to policy discourse. This is supported by Iny (Citation2017) who states that local government is fast becoming the second largest consumer of water resources. The availability of water directly affects South Africa’s socio-economic development, but the resource is dwindling. Since the demand patterns are not heeding the call for conservation practices, Iny (Citation2017) warns that by 2030 South Africa will be faced with a 17% water deficit and this will be progressively worsened by the changing climate. It is thus imperative that within the chain of the management of the resource, municipalities and their residents agree on the need for, and strategies to achieve, sustainable water services goals. The question is whether municipalities perform these functions adequately enough to achieve the objectives of the water policy in their poor communities.

3. Implementation of the Water Services Act of 1997 and the National Water Act of 1998 in poor communities

The NWA deals mainly with issues surrounding the macro-management of the supply and demand of water, while the WSA sets out guidelines for municipalities regarding the micro-management of the resource (Department of Water and Sanitation [DWAS] Citation2015). The main purpose of the NWA was to ensure that the nation’s water resources are protected, equally distributed, developed, conserved, managed and controlled as a precious resource of the country.

The WSA deals with matters related to the supply and management of water services to households and other users. It prescribes different tariff levels to ensure that water is used efficiently, with poor households being subject to the lowest tariff structure (Muller Citation2008). According to the WSA municipalities have the executive authority to provide services to their areas of jurisdiction. The WSA further states that:

A water service authority must ensure access to water as a realisation of a free basic right of citizens.

Access to water must be planned in such a way that sustainable livelihood and economic development is ensured through efficient and effective planning of water supply.

A water service authority must metre and keep records of all water supplied to consumers.

The regulation of water services provision and water services providers must be within an area of jurisdiction in line with the regulatory framework of the Department of Water Affairs.

The WSA must ensure the provision of effective, efficient and sustainable water services that also includes the conservation of the resource.

In the process of water provision, the WSA is also required to communicate activities related to, among other things, gender-sensitive hygiene promotion and the wise use of water.

These objectives of the WSA have the potential to redress historical inequalities in terms of water provision to the majority of black citizens in South African urban areas in an efficient and effective manner, if they are implemented as planned.

Arising from the WSA, the main strategy to achieve the first three of the above objectives is the provision of the first 6 kl for free to all households The strategy to implement this objective was to install metres in all households, to help households to monitor their consumption and detect any leakages that could cause unnecessary losses of water (Hay et al. Citation2012; Thompson et al. Citation2013). Operation Gcina’ Manzi (conserve water) was launched through the installation of metres (Tshabalala Citation2008) ().

Figure 1. Household water metering device. Source: Maphela (Citation2016).

The main question that was investigated in this research project is the extent to which the implementation of the NWA by the Johannesburg City Council in The main question that was investigated in this research project was: to what extent has the implementation of the NWA by the Johannesburg City Council in Soweto has contributed towards achieving the first three of the above WSA objectives?.

4. Research design and methodology

The study used a mixed methods case study research design. The first step was to critically assess the available scholarly, professional and technical literature on sustainable water management in poor communities as well as on water management in Soweto. The next step was to triangulate the above data with an empirical survey of residents in three different suburbs of Soweto and with key municipal officials and office bearers to determine their responses to water use perceptions and practices. A questionnaire was used to collect the data used in the study. Ethical clearance was granted by the Centre for Public Management and Policy (formally known as Sanlam Centre for Public Governance of the University of Johannesburg).

4.1. Case study sample and survey approach

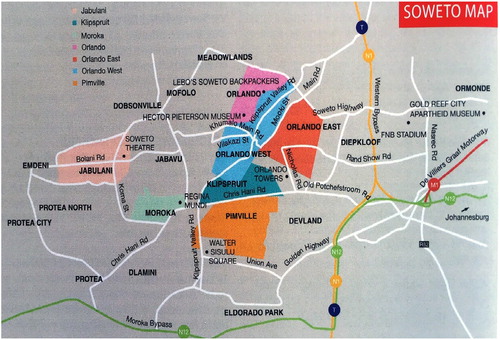

The study’s focus is on the provision of water by the Municipality of Johannesburg. The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) (Citation2015) states that municipalities are having an obligation of ensuring access to water as specified by the WSA. In this case the municipality provides the function of being a water services provider and may also collaborate with another institution to provide water services. The Johannesburg Water (JW) (Citation2015) business plan states that JW was established to provide these services and is wholly owned by the City of Johannesburg (COJ). The main function of JW is to deliver water and waste water services to the residents within the jurisdiction of COJ. Johannesburg Water purchases bulk water form Rand Water, who is the bulk supplier of Water in Gauteng (South African Local Government Association Citation2011). Thus, JW and Rand Water are the main supply-side stakeholders to a mixed housing development in Region D in Soweto, where the residents are the main demand-side stakeholders. There are different socio-economic classes residing in this region, with three distinct areas: apartheid four roomed matchbox houses, post-apartheid RDP houses, and post-apartheid bigger mortgage houses. Combining different socio-economic groups in one section came to be known as ‘mixed-income housing development’ (Onatu Citation2010). comprises a map of Soweto with the case study of Emndeni, Protea and Protea City (Maphela Citation2016).

Figure 2. Map of Soweto. Source: www.joburg.org.za (2019).

During the census of 2011 by Statistics SA, Soweto had a headcount of about 1.2 million inhabitants (Statistics SA Citation2017). In 2017, the population was at 1.3 million. At the time of the study in 2015 the population of this section was 1872 households from which a stratified sample of 20% was drawn. In each area 124 households were randomly selected. This mixed housing development section within Soweto was chosen because of the varied social dynamics found there. The survey samples for this study were inclusive of all the different socio-economic groups residing in the section, irrespective of the different dwelling structures. The author previously conducted surveys in this area, in 2015 (Maphela) and 2016 (Maphela). The survey conducted in 2013 found that 86% of RDP respondents were owners of their dwellings, while 14% stated that they were paying rent as tenants. The mortgage area was occupied mainly by people who could secure a loan from the bank, with a qualifying minimum salary.

The matchbox (four roomed) houses were built during the apartheid area to cater for the growing black ‘migrant labour’ population (Findley & Ogbou Citation2011; Bogatsu Citation2014). Upon occupying the house for a period of 30 years, the dweller obtained a title of ownership (Maphela Citation2016). At the time of the survey, all the occupants were the owners of the houses, not paying rent but liable for service fees for water, electricity and sanitation. In 1994 the new ANC-led government crafted the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) to correct the injustices of the past inter alia by assisting previously disadvantaged communities to secure basic houses, water and other services (Wessels Citation1999). Small core RDP houses were built mainly for people who had been squatters for a lengthy period (Southern African Catholic Bishops Conference Citation2017). After 1994, all municipal services had a portion of free basic provision, including water. shows the different types of housing.

Figure 3. Mixed housing development: apartheid 4-roomed house, post-apartheid RDP house, post-apartheid mortgaged house. Source: Maphela (Citation2016).

A six-point Likert scale-based questionnaire was used for all the groups. The questionnaire had three parts: A for general household data, B for the community culture and C for the implementation and management of the NWA. In total the questionnaire covered 52 questions. The following issues raised by means of the residents’ questionnaire are relevant for purposes of this article:

General levels of contact between the household and the municipality.

Specific consultation by the municipality at any stage with the household about water provision and use.

Levels of knowledge and understanding among households about the reasons why water demand management devices were installed in their yards.

Residents’ consumption of the free basic water allocation.

Residents’ payment of water consumed above the free basic provision.

Tampering with water metres.

Interviews were further conducted with three municipal officers. One councillor and two officials agreed to answer a few questions anonymously. The questions addressed to them were related to water consumption patterns, payments for water and the issue of large households that cannot afford to pay for water.

4.2. Results

The triangulated data indicated that the houses were not 100% owned by all the participants in all the areas that were surveyed. The mortgage section was the lowest in terms of ownership, at 73% ownership by the participants. On average the matchbox section had eight occupants per house, while both the RDP and the mortgage section had five occupants per house. The educational levels in the three types of households were found to be correlated with the household’s disposable incomes. shows the educational levels and the corresponding incomes.

Table 1. Education levels of the breadwinner and the corresponding income.

shows the nature of the different economic statuses of the three household types. The mortgage area was found to be the most affluent of the three in terms of education and corresponding incomes. The results enumerated in are confirmed by the budget reviews of 2013 and 2017. In 2013, the National Treasury (Citation2013) indicated that households that earn less than R2800 per month were eligible for some form of support by the government. The Budget Review of 2017 stated that R141-bn of the budget goes into supporting low income households (National Treasury Citation2017). Therefore, the validity of RDP and matchbox household income data is confirmed by official statistics.

shows the type of relationship that exists between the more affluent mortgage section of the area under investigation and the municipality of Johannesburg. The strength of contact between households and municipalities can serve as a barometer to assess the success and challenges of the WSA. It was important to establish if a relationship existed between the local government and the households that fall under its control because this relationship is an important part of the value chain in the water sector. According to the NWA, conserving water is an important component of the value chain.

It was established that mortgage households are of the view that the municipality simply makes decisions and implements them without consultation. This was contrary to the municipal officials’ views which emerged during the interviews with them. They asserted that the residents did not show up for briefings on the topic. The results also show that the water provision policy and practice was not popular in that area.

Various studies have found that the culture of non-payment of services and non-compliance are still very rife in the mortgage section because of the political history of these areas. Muller (Citation1999) pointed out in a letter to the stakeholders in water supply that one of the obstacles identified in water supply was the low levels of payment for services by communities. Lubbe & Rossouw (Citation2008) identified this challenge as emanating from the 1980s defiance campaigns initiated by communities as a way of undermining the apartheid system. A legal dispute between the households in a nearby section and the water services provider in this area illustrates the problem. The community in Phiri displayed dissatisfaction regarding the metres installed in their yards – they did not welcome this demand management device. As a result, a court case ensued between the residents of Phiri and JW. Though the Supreme Court of Appeal initially in its judgement found that the installation of metres was unlawful, the Constitutional Court found that the City’s Free Basic Water Policy included water metres and was within section 27 of the Constitution. The installation of metres was therefore found to be lawful, thus the initial ruling of the Supreme Court was set aside (Constitutional Court of South Africa, Case CCT 39/09/ZACC 28 2009) (Constitutional Court Citation2009). After this ruling JW continued with the process of installing metres, although surveys conducted after that time found that residents still held on to the old judgement. During the interviews of the municipal officials in Region D, this contradiction was raised. The councillors reiterated that there was no other strategy for monitoring the 6 kl other than that of installing water management devices. However, even in recent times, in some sections the devices have not been welcomed (Maphela Citation2016).

The RDP houses were built in terms of the policy for previously disadvantaged households who were mostly unemployed, were dependent on social grants or earned below the minimum wage, and therefore could not afford to buy a home for themselves. During surveys leading to this study in 2015, the owners of the houses confirmed that they received more than 6 kls of water a month and have a good relationship with the municipality in that they attend all the meetings convened by the councillors about new developments. This section has been provisioned with 10 kl of free water per household, which has promoted a good relationship.

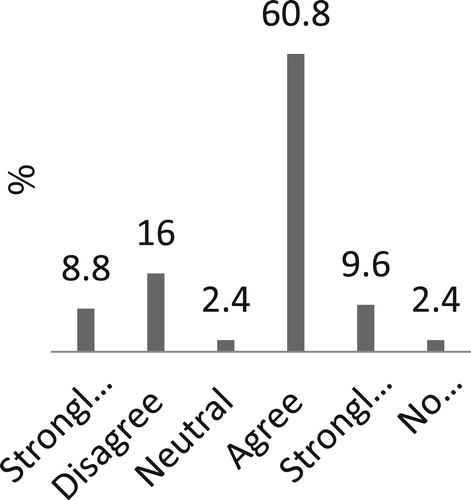

The main supplementary findings on the relationship between Johannesburg Municipality and the respective housing schemes are shown in .

Table 2. The household is part of the decision making in the water usage guidelines.

indicates that that the free basic RDP housing households are the most responsive and positive towards their water management system, for the reasons mentioned above. This situation, however, is different on the issue of whether the residents understand the reasons for the current water management system.

depicts similarities between the apartheid matchbox houses and the mortgage houses. These two sections seem to be struggling to understand that the installation of the devices was a strategy to mitigate wasteful consumption of water. The views of the respondents on their consumption of their free basic water allocations are summarised in .

Table 3. The household understands why water demand devices were installed.

Table 4. Every month your household only consumes the free basic water.

shows inconsistent results across the three socio-economic groups. Starting with the mortgage area, the results are consistent with their lifestyles and affordability. The mortgage section is more affluent than the other two, therefore the free basic provision cannot be enough because they have more water using devices.. Some of the households stated that during the month they buy more water as the free basic provision is not enough. It is not surprising that the neutral response is 40% because of the culture of non-payment. In the RDP section, even though they were receiving more water than the two other areas, they felt that the water provided was still not enough because of the number of occupants in the houses. One of the reasons was that they have shack dwellers in their yards, meaning that they have more than one family on the property.

The question about payment for water elicited interesting results, as shown in .

Table 5. The household supports the payment of water.

The NWA states that all South African must have a free basic provision of water of 6 kl, but those that occupy the RDP houses were entitled to 10 kl. This explains the results showing that they support paying for water consumption, because their provision is generally sufficient and they do not have to buy more water during the month. The owners of houses in the matchbox area strongly disagree with the policy. The mortgage area’s response is moderate because of the challenges of buying and selling of their houses; at some point their water affairs need to be in order for such transactions to proceed smoothly. It is not surprising that the positive response is largely from the owners of the RDP houses, as a result of the political issues surrounding the ownership of these houses. Findings of the survey conducted in 2013 and 2015 by Maphela in this area (ADD REFERENCE) were that the owners of these houses were afraid of losing their houses if they voiced their concerns. Sharpley (Citation2018) also found that the beneficiaries of RPD houses placed a high value on the houses they received form the ANC-led government. This could be one of the reasons that they did not wish to be open during the surveys conducted in 2013 about water consumption patterns. They also did not trust the rationale behind the study as they were by default largely the electorate of the African National Congress.

5. Impact of stakeholder relationships on the successful implementation of the National Water Act

Different levels of stakeholder relationships exist in the South African water sector, starting from the water boards all the way to the end user. This article focuses on the final end of the chain, i.e. the relationship between the water service provider i.e. municipalities, and the constituencies of the respective districts. If this relationship succeeds, the water policy will be effective.

The survey assessment indicates that at least the municipality of Johannesburg is trying to achieve the objectives of the NWA. The main challenge seems to be the lack of a meeting of minds between the municipality and poor communities that fall under their jurisdiction. This was confirmed by the three municipal officials interviewed in two different offices. One officer was responsible for water management in the four roomed and the RDP sections. The other two included a revenue collection officer and a councillor. The revenue officer explained that the revenues received for the water consumed by the residents was far lower than what the local office had expected to collect based on the water bill they received from the supplier. The political appointees indicated that they struggle with getting local residents to come to meetings they convene to discuss water consumption patterns. The third official was responsible for the mortgage section. It transpired that some households were sticking to the basic provision of 6 kl per month, thus not buying water at all. The revenues that were collected from those residents who were paying were also very low and were not enough to cover the bill of the water consumed by the residents.

The findings indicate that the potential achievement of water policy goals in the case study areas is compromised, mainly due to the following issues:

The implementation of the NWA by the Water Service Authority (the Municipality of Johannesburg) seems to be ineffective.

The Municipality of Johannesburg does not have a clear strategy of how to improve their implementation of the objectives of the NWA in the areas of study.

Fundamental differences seem to exist between the municipality and the residents about the nature of, reasons for, and compliance with, the current NWA implementation practices.

The residents do not see themselves as catalysts for water conservation as per the White Paper on Water of 1997, the NWA and the WSA.

One of the SDG goals is to ensure sustainable water resource availability and sustainable management of the resource. This goal is partly dependent on the successful implementation of the NWA.

6. Conclusions

The objectives of the water policy as expressed in the WSA and the NWA need to be achieved against the background of the urgency of climate change (Yi Citation2016). The implementation of the NWA in Soweto by the City of Johannesburg is problematic and does not achieve the stated goals. Policy is never static. It is a dynamic process that has to respond to changing conditions in society. Chan (as reported by Shuzhen Citation2017) advises that unexpected consequences are not predetermined, but neither are they random. Marume (Citation2016) concurs with Chan that policy cannot be static, as it has to be reformed and adapted continuously on the basis of experience, research, changing circumstances and needs.

suggests that the NWA’s agenda was to address issues of injustice within South African society. However, the implementation of the policy was obstructed by issues of entitlement (Fjelstad Citation2004). Citizens did not adjust their old consumption patterns of water to make room for the new ideology of sustainable consumption of the resource according to the guidelines of the new policy.

Figure 4. Close relationship between RDP households and local government. Source: Adapted from 2015 Survey.

The new post-apartheid government was faced with a culture of non-payment of services. Residents in poor communities took the NWA literally, namely, that it only conferred rights. They did not pay attention to the inherent responsibilities also associated with curbing wastage. There is a need now for an urgent change in direction.

The latest challenges of regionally variable water shortages in South Africa call for deliberate and collaborative action from all stakeholders in water conservation. Authors such as Muller (Citation2008) state that almost all South Africans already have access to basic water provision. The African Minister’s Council on Water (World Bank Citation2015) stated that access to water infrastructure in South Africa improved from 58% in 1994–91% in 2009, bringing South Africa into line with the requirements of the Millennium Development targets for water supply and sanitation.

Politics in water provision have to be minimised because climate change calls for urgent efforts to conserve water. Immediate rehabilitation of the relationship between municipalities and residents in relation to curbing water wastage through proper governance could ensure that the nation has sufficient water to survive. Water policy experts have noted that the NWA was faced with challenges from the onset of its implementation. Fjelstad (Citation2004) pointed out that the implementation of the restorative water policy has faced major challenges from residents because residents understand the free basic provision of services differently. Muller et al. (Citation2009) warned that the success of water management in South Africa could not be pinned solely on the availability of the resource, but also on the institutional capability of delivering it in an efficient and effective manner. Thus, the resource can be managed if the right decisions are taken at the right time within the policy wheel.

The NWA objectives should be significantly adapted to avoid the dire implications of not complying with longer term climate change imperatives. This requires residents of all socio-economic groups to accept co-responsibility for achieving the desired outcomes. Until the relationships between the municipality and the residents are improved and a mind shift towards compliance and cooperation is instilled in all socio-economic groups, the water management challenges facing South African communities will persist.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bester, E, 2018. The Dube story. http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/dube-story Accessed 30 September 2018.

- Blight, GE & Fourie, AB, 2005. Experimental landfill caps for semi-arid and arid climates. Waste Management & Research 23(2), 113–25. ISWA 2005. doi:10.1177/0734242X05052458.

- Blignaut, J & Van Heerden, J, 2009. The impact of water scarcity on economic development initiatives. Water SA 35(4), 415–20.

- Bogatsu, K, 2014. Jarateng: making social-ends meets by embracing public living. Masters dissertation, University of Witwatersrand.

- Colvin, C, Muruuven, D, Lindley, D, Gordon, H & Schachtschneider, K, 2016. Together investing in the future of South Africa’s freshwater ecosystem. WWF-SA 2016. Water: facts and futures. https://water.cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/wwf009_waterfactsandfutures_report_web__lowres_.pdf Accessed XX September 2018.

- Constitutional Court of South Africa, 2009. Case CCT 39/09/ZACC 28 2009. https://cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Mazibuko-Constitutional-Court-judgment.pdf Accessed 20 April 2019.

- Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 1998. The white paper on local government. Building of a democratic system of local government in South Africa. http://www.cogta.gov.za/cgta_2016/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/whitepaper_on_Local-Gov_1998.pdf.

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, 1956. Water Act No 54 of 1956. http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/saf1272.pdf Accessed 10 September 2018.

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, 1997. Water Services Act, No. 108 of 1997. http://www.dwaf.gov.za/Documents/Legislature/a108-97.pdf Accessed 10 September 2018.

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, 1998. National Water Act No. 36 of 1998. www.dwa.gov.za/documents/legislature/nw_act/NWA.pdf Accessed 21 April 2019.

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, 2005. Water and sanitation business: The roles and responsibilities of local government and related institutions. http://www.dwa.gov.za/IO/Docs/CMA/WMI%20Poster%20Booklets/Roles%20&%20Responsibilities%20of%20Local%20Government%20and%20Related%20Institutions.pdf Accessed 21 June 2015.

- Department of Water and Sanitation, 2015. Revision of the norms and standards for setting water services tariffs in terms of section 10 of Water Act 1997. Gazette No. 39411. http://www.dwa.gov.za/Projects/PERR/documents/Norms%20&%20Standards.pdf Accessed 15 September 2013.

- Donnenfeld, A, Crooke, C & Hedde, S, 2018. A delicate balance: water scarcity in South Africa. Southern Africa Report 13. Institute of Security Studies, Pretoria. https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/sar13-2.pdf Accessed 24 April 2018.

- Filofac, FA, 2007. National water policy and water services at the extremes: What challenges must be faced in bridging the gap? Learning from the South African experience. African Water Journal 1(1), 5–22.

- Findley, L & Ogbou, L, 2011. South Africa: From township to town. Places Journal. doi:10.22269/111117.

- Fjelstad, O-H, 2004. What’s trust got to do with it? Non-payment of service charges in local authorities in South Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies 42(4), 539–62.

- Francis, R, 2005. Water justice in SA: natural resources policy at the intersection of human rights, economics & political power. Georgetown International Environmental Law Review 18(1), 149–96.

- Goldin, JA, 2010. Water policy in South Africa: Trust and knowledge as obstacles to reform. Review of Radical Political Economics 42(2), 195–212. doi:10.1177/0486613410368496.

- GreenCape, 2017. Water: market intelligence report. https://www.greencape.co.za/assets/Uploads/GreenCape-Water-MIR-2017-electronic-FINAL-v1.pdf Accessed 10 October 2018.

- Hay, ER, Riemann, K, Van Zyl, G & Thompson, I, 2012. Ensuring water supply for all towns and villages in the Eastern Cape and Western Cape Provinces of South Africa. Water SA 38(3), 437–44. doi:10.4314/wsa.v38i3.7.

- Herrfahrdt-Pähle, E, 2010. South African waster governance between administrative and hydrological boundaries. Climate and Development 2(2), 111–27.

- Hoffman, MT, Carrick, PJ, Gillson, L & West, AG, 2009. Drought, climate change and vegetation response in the succulent karoo, South Africa. South African Journal of Science 105(1–2), 54–60.

- Iny, A, 2017. Scenarios for the future of water in South Africa. The Boston Consulting Group, WWF-SA, Cape Town.

- Jaime-Castillo, AM & Marques-Perales, I, 2014. Beliefs about social fluidity and preferences for social policies. Journal of Social Policy 43(3), 615–33. doi:10.1017/S0047279414000221.

- Johannesburg Water, 2015. Providing water. providing life. Johannesburg water business plan/v4. https://www.johannesburgwater.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Business-Plan-2015_16.pdf Accessed 10 September 2018.

- Karodia, H & Weston, D, 2001. South Africa’s new water policy and law. In Abernethy, CL (Ed.), Intersectoral management of river basins. Proceedings of an International Workshop on Integrated Water Management in Water Stressed River Basins in Developing Countries: Strategies for Poverty Alleviation and Agricultural Growth, 16–21 October 2000, Loskop Dam, SA, International Water Management Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- Knüppe, K & Meissner, R, 2016. Drivers and barriers towards sustainable water and land management in the Olifants-Doorn water management area, South Africa. Environmental Development 20, 3–14. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2016.09.002.

- Lubbe, D & Rossouw, C, 2008. Debt of local authorities in South Africa: Accounting realities leading to ethical, social and political predicaments. African Journal of Business Ethics 3(1), 19–27.

- Maphela, B, 2016. Critical assessment of South Africa’s water policy. PhD thesis, University of Johannesburg.

- Marume, SBM, 2016. Public policy and factors influencing public policy. International Journal of Engineering Science Invention 5(6), 6–14.

- Mathipa, KS & Le Roux, CS, 2009. Determining water management training needs through stakeholder consultation: Building users’ capacity to manage their water demand. Water SA 35(3), 253–60. doi:10.4314/wsa.v35i3.76762.

- Muller, M, 1999. Water conservation and demand management national strategy framework. May Draft (1999) Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Pretoria. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/watermanfr0.pdf Accessed 15 October 2017.

- Muller, M, 2008. Free basic water-a sustainable instrument for sustainable future in South Africa. Environment and Urbanization 20(1), 67–87. doi:10.1177/0956247808089149.

- Muller, M, 2017. Understanding the origins of Cape Town’s water crisis. Civil Engineering June 2017. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2995937 Accessed 1 June 2019.

- Muller, M, Schreiner, B, Smith, L, Van Koppen, B, Sally, H, Aliber, M, Cousins, B, Tapela, B, Van Der Merwe-Botha, M, Karar, E & Pietersen, K, 2009. Water security in South Africa. Development Planning Division. Working Paper Series No: 12. DBSA, Midrand. https://www.dbsa.org/EN/About-Us/Publications/Documents/DPD%20No12.%20Water%20security%20in%20South%20Africa.pdf Accessed 21 April 2019.

- National Treasury, 2013. Social security and social wage. Budget Review 2013. http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2013/review/chapter%206.pdf Accessed 21 June 2015.

- National Treasury, 2017. Budget highlights. National Treasury. http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2017/sars/Budget%202017%20Highlights.pdf Accessed 15 June 2015.

- Odendaal, N, 2013. Water security critical to SA’s economy. https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/water-security-critical-to-sas-economy-2013-03-22 Accessed 20 February 2018.

- Onatu, GO, 2010. Mixed income housing development strategy: Perspective on Cosmo city, Johannesburg, South Africa. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 3(3), 203–15. doi:10.1108/17538271011063870.

- Pienaar, GJ & Van Der Schyff, E, 2007. The reform of water rights in South Africa. Law Environment and Development Journal 3(2), 179–94.

- Reed, HE, 2013. Moving across boundaries: migration in South Africa, 1950–2000. Demography 50(11), 71–95. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0140-x.

- Republic of South Africa, 1996. The constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act No 108 of 1996). Government Gazette 378 (17678). Government Printer, Cape Town.

- Roux, NL, 2002. Public policy making and policy analysis in South Africa amidst transformation, change and globalisation: Views on participants and role players in the policy analytical procedure. Journal of Public Administration 37(4), 418–37.

- Sharpley, GG, 2018. Government housing rectification programme and practice in South Africa: A case study of three selected Eastern Cape communities. D.Phil, University of the Western Cape.

- Shuzhen, S, 2017. Putting the ‘public’ in public policy. AsianScientist. March. https://www.asianscientist.com/2017/03/features/putting-public-public-policy/ Accessed 15 March 2018.

- Smith, L, 2009. Municipal compliance with water service policy: A challenge for water security. Development Planning Division. Working Paper Series No.10. DBSA, Midrand. https://www.dbsa.org/EN/About-Us/Publications/Documents/DPD%20No10.%20Municipal%20compliance%20with%20water%20services%20policy-%20A%20challenge%20for%20water%20security.pdf Accessed 20 April 2018.

- Solomons, I, 2013. SA’s economic pathway water intensive. http://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/sas-water-supplies-and-infrastructure-a-concern-2013-05-31/searchString:SA%27s+economic+pathway Accessed 17 June 2017.

- South African Local Government Association, 2011. Water service local regulation case study report for the City of Johannesburg. https://www.salga.org.za/Documents/Municipalities/Guidelines%20for%20Municipalities/City-of-Joburg-case-study-local-regulation.pdf Accessed 17 September 2018.

- Southern African Catholic Bishops Conference, 2017. RDP housing: Success of failure? http://www.cplo.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/BP-432-RDP-Housing-May-2017.pdf Accessed 17 September 2018.

- Statistics SA, 2017. The state of basic services delivery in South Africa: In-depth analysis of the community. Survey data report No. 03-01-22-2016. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2003-01-22/Report%2003-01-222016.pdf Accessed 12 March 2019.

- Tewari, DD, 2009. A detailed analysis of the evolution of water rights in South Africa: an account of three and a half centuries from 1652 AD to present. Water SA 35(5), 693–710. doi:10.4314/wsa.v35i5.49196.

- Thompson, L, Masiya, T & Tsolekile de Wet, P, 2013. User perception and levels of satisfaction of water management devices in Cape Town and eThekwini. Report to the Water Research Commission. WRC Report No. 2089/1/3. http://www.wrc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/2089-1-13.pdf.

- Tshabalala, T, 2008. Jo’burg water meters under spotlight after court ruling. Mail & Gaurdian, 10 May. https://mg.co.za/article/2008-05-10-joburg-water-meters-under-spotlight-after-court-ruling Accessed 1 October 2018.

- United Nations Development Programme, 2017. Sustainable development goals. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=2ahUKEwjE0sGb2pLjAhXoWxUIHZk8CCIQFjADegQIBBAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.undp.org%2Fcontent%2Fdam%2Fundp%2Flibrary%2Fcorporate%2Fbrochure%2FSDGs_Booklet_Web_En.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1gJz7VYHrZc_cPzfEw4DOI Accessed 1 July 2019.

- Uys, M, 1996. A structural analysis of the water allocation mechanism of the Water Act 54 of 1956 in the light of the requirements of competing water user sectors. Water Research Commission Report 406/2/96 Volume II. http://www.wrc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/406-2-96.pdf Accessed 20 March 2017.

- Van Vuuren, J, 2009. Preserving our rivers’ right to survival. Water Wheel 8(3), 23–7.

- Walker, WE, Marchaua, AJV & Swanson, D, 2010. Addressing deep uncertainty using adaptive policies: introduction to Section 2. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 77(6), 917–23. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2010.04.004.

- Wessels, D, 1999. South Africa’s reconstruction and development programme. “A better life for all”. Journal of Social Sciences 3(4), 235–43. doi:10.1080/09718923.1999.11892242.

- World Bank, 2015. Water supply and sanitation in South Africa: turning finance into services for 2015 and beyond. An AMCOW country status review; water and sanitation program. World Bank Group, Washington, DC. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/330331468007268303/Water-supply-and-sanitation-in-South-Africa-turning-finance-into-services-for-2015-and-beyond Accessed 20 September 2018.

- World Cup Legacy Report, 2011. South Africa is considered to be a water scarce country. https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/water.pdf Accessed 10 April 2019.

- Yi, I, 2016. Policy innovations for transformative change: Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). http://www.unrisd.org/UNRISD/website/document.nsf/(httpPublications)/92AF5072673F924DC125804C0044F396?OpenDocument Accessed 23 May 2017.

- Ziervogel, G, New, N, Van Garderen, EA, Midgley, G, Taylor, A, Hamann, R, Stuart-Hill, S, Myers, J & Warburton, M, 2014. Climate change impacts and adaptation in South Africa. WIRES Climate Change 5(5), 605–20. doi:10.1002/wcc.295.