ABSTRACT

The literature on women entrepreneurs indicates that they have a positive influence on national economic growth and employment levels, yet the lived experience of women business owners in the highly constrained setting of South African townships has not been reported in academic literature. This study thus explored the role of the various stakeholders by conducting semi-structured interviews with 40 women entrepreneurs in eight townships, as well as leaders of five small business support organisations. The research provides a unique insight into the contextual complexities faced by these female business owners, offers a model of their stakeholder relationships, and identifies inhibiting and enabling factors in these relationships.

1. Introduction

Women-owned businesses have been recognised as being vital to the overall growth of entrepreneurship, economic growth, poverty alleviation and job creation in many countries (Chirwa, Citation2008; Maphalla et al., Citation2009; Nmadu, Citation2011; Brush & Cooper, Citation2012; Rabbani & Chowdhury, Citation2013), which is why Malebana (Citation2017) noted that policy makers are focused on how economic growth via entrepreneurial activity can be stimulated.

Despite Black African women being the single largest segment of self-employed people in South Africa (Witbooi & Ukpere, Citation2011), these female entrepreneurs are not performing as well as their counterparts in other emerging economies (Kelley et al., Citation2013). In addition, although women tend to own more businesses than men in the informal sector, the proportion of female-owned businesses decreases as the business size and sophistication increases (Kelley et al., Citation2013).

Most studies have focused on poor marketing, financial challenges and inefficient operational systems as reasons for the failure of small enterprises (Seeletse, Citation2012), however an unpublished study of women entrepreneurs in one township in South Africa pointed to another possible reason for business failure – that women often suffer mental, physical and emotional abuse as a consequence of their success and that their relationships tend to inhibit business growth (Treharne, Citation2011). This alludes to an area that has not been explored sufficiently, i.e. the possibility of psychosocial reasons contributing to the failure or lack of growth of women-owned businesses. Although there is a body of literature on women in the workplace, women managers in the informal sector have rarely been the focus of academic study. The intention of this study was to explore the lived experience of these businesswomen in the resource-constrained townships of South Africa through the lens of their stakeholder relationships.

2. Literature review

2.1. Entrepreneurship employment in South Africa

According to the World Bank, the small, medium and microenterprise (SMME) sector represents 90% of firms in South Africa (IFC, World Bank Group, Citation2018), contributes 37% to the GDP and provides 68% of the country’s employment (Bradford, Citation2007). Preisendorfer et al. (Citation2012) asserted that the future of the South African economy requires an expansion of Black African entrepreneurial businesses. Small business failure within two years of registration in South Africa is placed at between 70% and 80%, with the reasons for this failure being cited as a lack of access to finance or markets, a lack of business skills, burdensome red tape, poor local economic conditions, the cost of labour, and the concentrated nature of the economy (Ligthelm, Citation2011; SBP, Citation2013; Fatoki, Citation2014; Chimucheka & Mandipaka, Citation2015). Business development efforts to raise the levels of entrepreneurial success have not resulted in the desired increase (Herrington et al., Citation2014).

2.2. Business in townships

In accordance with Welter’s (Citation2011) suggestion, based on Johns’s (Citation2006) framework, that there is a need to study the multi-faceted contexts in entrepreneurship, we applied a wide context lens to South African township businesses.

In South Africa, the rate of unemployment is estimated to be 26.7%. A study of the unemployed indicates that the worst affected are Blacks, females and young people (Statistics SA, Citation2018), the majority of whom reside in townships. Townships are defined as areas that were historically designated under apartheid legislation for exclusive separate occupation by people socially and economically classified as Africans, Coloureds and Indians (Lester et al., Citation2009). These township areas were relegated to the outskirts of cities, which further entrenched the ‘geographical marginalisation’ of their residents from the economy (Jurgens et al., Citation2013). These areas usually have prevailing poverty, low-income levels amongst the employed and weak institutional structures, creating a complex environment for the operation of businesses (Mbonyane & Ladzani, Citation2011). With 60% of households in metropolitan areas being based in townships, the national agenda of small business development within these communities is critical (Lester et al., Citation2009; Njiro et al., Citation2010).

Generally, regardless of the gender of small venture owners, they are marginal performers within their markets (Storey, Citation2011). Most township businesses are very small with an income of significantly less than R1 million per annum and fewer than 10 employees (Njiro et al., Citation2010). Most studies indicate a high rate of failure of township-based businesses, with a few studies documenting their extensive challenges, including technological and legal challenges, high levels of crime, poor infrastructure, failure to satisfy customers or to treat employees well, lack of business knowledge and poor financial management practices (Maphalla et al., Citation2009; Ligthelm, Citation2011; Mbonyane & Ladzani, Citation2011; Seeletse, Citation2012). Further, business development support agencies are usually found in cities and have been found to be largely unavailable or inaccessible in townships (Chiloane & Mayhew, Citation2010; Mbonyane & Ladzani, Citation2011; Herrington et al., Citation2014).

Preisendorfer et al. (Citation2014) found that respondents in a township had a favourable view of opportunities to start a business and of the social status associated with being an entrepreneur. However, the researchers opined that there was a high risk of social disapproval should the businesses fail, or a sense of distrust if they were too successful. This has led to a low-trust culture, yet the building of social capital with stakeholders is recognised as a key ingredient to business growth (Preisendorfer et al., Citation2014). A study by Ewere et al. (Citation2015) on business start-ups in townships mentioned several factors that contribute to the success of enterprises in this specific location, including the entrepreneur’s membership of organisations, whether s/he had self-employed friends, and support from his/her personal network.

These unique dimensions of social, spatial, historical, societal and institutional contexts (Welter, Citation2011) show the need for an in-depth study on the business owners in South African townships.

2.3. Women entrepreneurs

Ahl & Marlow (Citation2012) pointed to the gender bias in entrepreneurial literature, where the discourse underpinning entrepreneurial representation is fundamentally masculine. Ekinsmyth (Citation2013) also emphasised that a more feminist perspective on women entrepreneurship is required to establish a female norm of entrepreneurship that is not necessarily expected to imitate the male norm. However, Barbasi et al. (Citation2011) found that in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, women entrepreneurs have significantly smaller enterprises than men and concentrate their businesses on clothing manufacturing, retail, tourism and restaurants. In addition, Al-Dajani & Marlow (Citation2013) showed the gendered relationship between entrepreneurship and empowerment, contextualised within the lives of Palestinian migrant subordinated women.

South Africa’s racially segregated and discriminatory past has led to Black African women often viewing themselves as ‘third or fourth-class citizens’, carrying the burden of a ‘double negative’ of being both Black and women. The social and psychological implications of this are that women entrepreneurs suffer both from the gender gap and the consequences of historical and cultural prejudices (Witbooi & Ukpere, Citation2011). Several studies in the USA and India also highlighted this double jeopardy due to the intersectionality of gender and race (Sharma, Citation2014; Shelby Rosette et al., Citation2016).

Kamberidou (Citation2013) referred to obstacles created by gender stereotyping, arguing that it is essential to integrate the gender dimension into discussions on entrepreneurship. In South Africa, there is an unfavourable societal perception of entrepreneurship as a career that adds a further layer of difficulty to small business ownership by women (Herrington et al., Citation2014). O’Neill & Viljoen (Citation2001) discussed the need to advocate for changing the roles for women in families and emphasised the need for acceptance of women as entrepreneurs while providing ways to build their self-confidence.

Rabbani & Chowdhury (Citation2013) described a link between the empowerment of women, the building of just societies and achieving targets for national development. A 2008 World Bank-Goldman Sachs report found that investment in women entrepreneurs is one of the most effective ways to reduce inequality, facilitate inclusive economic growth impacting on GDP growth, and have a multiplier effect on the entrepreneur’s family and community (World Bank-Goldman Sachs, Citation2008). Yet the majority of women entrepreneurs in developing economies, and particularly in South Africa, are ‘locked into’ the informal sector, running survivalist micro-businesses (Nmadu, Citation2011; Chaney, Citation2014). In a literature review study, Ascher (Citation2012) showed that women entrepreneurs have been found to face several obstacles – from a lack of experience and financial and social capital, to gender discrimination rooted in stereotypical views on the traditional roles of women and domestic issues. This points to a unique set of enabling and inhibiting gender-based factors which have not been studied in the township setting.

Research has shown that female entrepreneurship is a ‘gendered phenomenon’ that requires nuanced study from a female perspective (Ekinsmyth, Citation2013; Jennings & Brush, Citation2013). While female entrepreneurs outnumber male entrepreneurs in South Africa, especially within the informal and microenterprise sectors, their ratio is still well below those in comparable emerging economies (Herrington et al., Citation2014). Calás et al. (Citation2009) emphasised that women and men entrepreneurs are perceived as being fundamentally different in research, which produces and reproduces gendered entrepreneurial discourse. Entrepreneuring is therefore socially constructed within the prevailing gendered order where masculinity is dominant (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2012).

2.4. The ecosystem’s stakeholder relations impacting women entrepreneurs

An ecosystemic approach which takes a holistic view of all stakeholders related to the subject of enquiry was used in this study (Isenberg, Citation2010). Ecosystems refer to assessing a phenomenon within a complex network or an interconnected system. Mattaini & Meyer (Citation2002) described the ecosystems approach as a way of seeing the person and the environment in their interconnected and multi-layered reality to comprehend complexity and avoid oversimplification. Freeman (Citation1984:46) defined a stakeholder as ‘a group or individual who is affected by or can affect the achievement of an organisation’s objectives’. No studies could be found that examined the stakeholder challenges in small businesses run by women in the informal sector in South Africa. Psychosocial refers to the interrelation of social factors and individual thought and behaviour (Oxford Dictionary, Citation2015).

In terms of stakeholder relations, acceptance has to start in the home, yet the contribution of the spouse or partner to the woman manager’s emotional and mental well-being is an often-overlooked area of study (Nikina et al., Citation2013). Stakeholder support, such as that from family and friends, has a significant positive impact on women entrepreneurs and their business success (Jabeen et al., Citation2015). Female owners of micro and small businesses in one township in South Africa reported that their challenges included social and cultural barriers, as well as behavioural and psychological barriers such as a lack of self-confidence (Treharne, Citation2011). Women appear to be most dependent on social relationships for moral and emotional support during the initial years of their business start-up (Kuada, Citation2009).

Research into the issues and challenges faced by women entrepreneurs in India indicated that because of a patriarchal bias, entrepreneurial traits such as ambition, self-confidence, innovativeness, achievement motivation and risk-taking ability were inhibited (Sharma, Citation2014). With regards to entrepreneurship and motherhood, women have described that they are not usually relieved of household responsibilities and still remain the primary parent, emotional nurturer, and housekeeper (Schindehutte et al., Citation2003). Gender asymmetry still persists (Chengadu & Scheepers, Citation2017). However, one study indicated that the legacy of exclusion under apartheid and their continued exclusion from urban networks has culminated in a stronger sense of belonging and commitment to the township by women entrepreneurs (Grant, Citation2013).

2.5. Conclusion to the literature review

In an allusion to the need for research that focuses on the relationship aspects of entrepreneurship, Rauch & Frese (Citation2007) invited researchers to put the person back into research. While a body of literature points to the importance of female entrepreneurship for economic growth, innovation, job creation, poverty alleviation and the empowerment of marginalised groups, a gap exists in the study of women entrepreneurs in the unique context of townships in South Africa and the role that their stakeholders play in their success or failure. Welter’s (Citation2011) seminal work on the importance of context was based on theory development from a literature review. Only an empirical study in Germany on the full context of entrepreneurship (Ettl & Welter, Citation2010) could be found. The psychosocial experience of women business owners in townships appears to have been largely ignored and not studied from an ecosystem approach.

3. Research questions

The specific questions that provided a guide to this research were:

Research question 1: What are the psychosocial challenges experienced by women entrepreneurs in townships with their stakeholders?

Research question 2: What are the coping mechanisms used by women business owners in townships?

Research question 3: How does each stakeholder group enable the female entrepreneur in townships?

Research question 4: How does each stakeholder group inhibit the female entrepreneur in townships?

4. Research methodology

4.1. Population and sample

As no other research in this precise area of study could be found, it was decided to use an exploratory, inductive research process using a qualitative methodology through face-to-face interviews (Saunders & Lewis, Citation2012).

Two populations were involved in the study. Sample A were 40 women entrepreneurs who operated their own businesses within eight townships – Alexandra, Soweto, Ivory Park and Mamelodi in Gauteng, KwaMashu and Chatsworth in Kwazulu-Natal, and Khayelitsha and Mitchell’s Plain in the Western Cape. A combination of quota and purposive sampling methods was used based on geographic location, age, racial group and business type and size (Saunders & Lewis, Citation2012). gives details of the interviewees.

Table 1. Demographics of the interviewees.

In terms of family structure, 18 were married, 11 were single, 6 were divorced, 5 were widowed, and 36 had children. The types of businesses were varied and included catering, day-care facilities, bed and breakfast establishments, hardware stores, steel fabrication and office maintenance. These small businesses had been operational for between three months and twenty-five years, with the average being eight years. Sample B consisted of five CEOs or regional managers (three female, two male) of support organisations that assist small businesses in townships. These organisations were either non-profit, private or government agencies. All had a physical presence in the townships.

4.2. Interview guide and data collection

The semi-structured interviews were based on interview guides that were framed by the research questions above. The interview guidelines were piloted with two respondents to ensure they were relevant, achievable and understandable, and then adjusted (Saunders & Lewis, Citation2012). The questions were primarily open-ended to ensure that valid responses were obtained without the influence of being given constructs. The interviews lasted on average 30 min and were conducted in English. Although most interviewees spoke sound English, a translator attended all the interviews to translate questions that were not understood and to provide any necessary interpretation of the answers. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the university in which this study took place and all interviewees signed consent forms.

4.3. Analysis and limitations

The analysis took the form of content analysis. The raw data were first assessed for themes and categorised accordingly (Saunders & Lewis, Citation2012). Rank-ordered tables were developed to show the prioritisation of the findings and to enable the researchers to draw patterns.

As most interviews occurred in their places of business, the interviewees may have been distracted by work concerns or felt unable to share some confidential information. As the study was conducted in only three provinces with 40 entrepreneurs, the findings cannot be generalised to all female business owners in all townships in South Africa.

5. Results

5.1. Research question one

What are the psychosocial challenges experienced by women entrepreneurs in townships with their stakeholders?

The interviewees were asked if there is a difference in the support provided to male and female entrepreneurs in townships. The results are provided below ().

Table 2. Perceived differences in support of male and female entrepreneurs.

The majority of interviewees believed that male entrepreneurs are provided with more support, citing examples such as ‘most men believe that women still belong in the kitchen, so if you try to start something you don’t get support; people criticise you negatively instead of building and supporting you’ and ‘even organisations set up to help, such as the local Business Chamber, elect only men in leadership positions’. These findings support the research of Ahl & Marlow (Citation2012) on gendered entrepreneurship. Another interviewee said that ‘as a woman, everyone wants me to have a small little business in the corner, not to flourish. I can’t have big dreams but males are allowed to dream’. This alludes to the women being ‘allowed’ by the community to own businesses that supplement their household priorities (Ekinsmyth, Citation2013), but not to be too ambitious. This confirms the finding of societal views being an inhibitor to growth (Rabbani & Chowdhury, Citation2013).

Five of the eight interviewees who felt there was no difference, came from the hospitality industry in one township, and were provided with assistance from a specific company and the local tourism promotion agency.

Most business development service providers believed that there was a gender-based difference, with men enjoying ‘more support from their peers and families’, yet only one customised its services for women. One service provider said

when it comes to government tenders, if you’re a man it is seen that you have more credibility; as a woman, you’re seen as an exception, not the norm. If they apply for tenders, there is the possibility of men asking them for a sexual relationship.

Table 3. Stakeholder challenges experienced by the female entrepreneurs.

The data provide a disturbing picture of the lived experiences of these female business managers. Three themes emerged in the analysis.

5.1.1. Gender

Gender-based discrimination was experienced from staff, customers, suppliers and competitors, and ranged from customers attempting to question the credibility of the female entrepreneurs through to malicious or criminal activity, perceived to demonstrate that it is ‘easier to take advantage of a female’. One interviewee said, ‘men will never treat us as equals; they will always feel like we don’t know what we are doing’. Another interviewee felt that there was still a belief that ‘men have more power to control staff’ and that ‘when a man says something, he’s serious, but when a woman says something, it’s taken lightly’. Two interviewees directly linked the lack of support to cultural aspects of being Black South African women, referring to traditional beliefs of Black males that women should be fulfilling domestic responsibilities as opposed to building businesses. There appeared to be a resignation to ‘this is the way things are’.

One interviewee said, ‘If I had the confidence, I would grow the business more and more’, while another mentioned that her image of a successful entrepreneur is male, and that she ‘truly believes for a business to do well, it must be run by a man’. The finding of a lack of confidence in one’s capability to create and grow a business is aligned to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s statement that the confidence of South African entrepreneurs in their ability to start a business is ‘alarmingly low compared to other sub-Saharan countries’ (Herrington et al., Citation2014).

One interviewee mentioned that clients would often ask her, ‘Are you working for him?’ in reference to her male employee, while another said that men tend to dislike her doing maintenance work in her business, saying she should be doing the cooking instead: ‘they are trying to put me somewhere; to remove me from being a businesswoman, trying to tell me where I belong’. This links to research conducted in India where constraints to the growth of businesses owned by women were found to be, among others, the male-dominated societal norms and not ‘being taken seriously’ (Sharma, Citation2014). Treharne (Citation2011) similarly found that women who were ‘too successful’ were often intimidated and left ‘feeling like societal outcasts’. Communities thus appear to have an unspoken view on what is a socially acceptable level of growth and success for a woman entrepreneur and her business (Rabbani & Chowdhury, Citation2013).

When the service providers in Sample B were asked about the psychosocial challenges these women face, it was apparent that none of them had previously considered this. One advisor mentioned that these challenges are linked with the struggle that women entrepreneurs have to market themselves – either due to safety issues or because they are more reserved. Another explained that women are not pushed to succeed and that traditional views restrict them, mentioning that ‘they can’t work until 10pm as a male entrepreneur would – the push is on them meeting their role as a married woman at home and not on succeeding as entrepreneurs’. Interestingly, two service providers felt that no psychosocial challenges were experienced by women entrepreneurs at all, as ‘times have changed and men and women operate the same now’.

5.1.2. Entrepreneurship as a career

As an initial response to their choice of entrepreneurship as a career option, 18 interviewees had the support of families and friends, but 13 found they were unsupportive, sceptical or discouraging. Nine experienced their families and friends having mixed reactions, starting off being discouraging but becoming supportive once the entrepreneur had achieved a level of success. This is aligned to Ascher’s (Citation2012) findings, where the author discussed the impediments to entrepreneurship for women, especially those rooted in traditional views of stereotypical roles for women and domestic issues. Sharma (Citation2014) found these views impeded the ambition, risk-taking and innovativeness of the women entrepreneur.

5.1.3. Township context

The interviewees felt that the lack of marketing and support for townships had a direct bearing on their ability to grow their businesses. One interviewee mentioned that ‘local whites don’t even know Soweto; they ask, ‘Is it safe?’ That makes me mad’. The location of the businesses also influenced their ability to access new markets due to the perception that townships are unsafe and that products manufactured there would be of inferior quality. However, an advantage of working in a township was that there is perceived greater information sharing – an interviewee explained that should she want to start another business, advice would be freely available from people currently working within that sector. Additionally, clients were also a source of encouragement, helping to enhance the sense of purpose and fulfilment for the women entrepreneur. This contradicts research in a township that indicated that there was a high risk of social disapproval should businesses fail, or a sense of distrust if they were too successful (Preisendorfer et al., Citation2014).

These findings show that there is a multi-layered psychosocial relationship ecosystem that women entrepreneurs in townships work within, and that these have a bearing on their self-perceptions.

5.2. Research question two

What are the coping mechanisms used by women business owners in townships?

A question regarding the coping mechanisms that female entrepreneurs use provided a further understanding of their psychosocial support systems. In an ecosystem approach, it is important to understand thoughts and behaviours in relation to networks and relationships (Mattaini & Meyer, Citation2002). The responses are shown below ().

Table 4. Methods used to cope with challenges.

The reticence of women to answer this question and the fact that a quarter of them do not share their concerns with anyone implies that the interviewees tend not to dwell on their challenges and are resigned to continuing with their responsibilities without any specific type of support. The findings further indicate that family and friends tend to be the providers of most support, usually in the form of emotional care and encouragement, as well as some assistance with marketing. This corresponds with the findings of a study conducted amongst Emirati female entrepreneurs, which indicates that family structures offer an important contribution to business success (Jabeen et al., Citation2015).

The finding that women entrepreneurs rely as much on faith-based groups as they do on family to help them cope with challenges is new to this field of study and is thus of importance. It was not within the scope of this research to discuss if the support is religious in nature or comes from being with a like-minded group of friends. The lack of reporting of faith-based support as an important method of coping in other studies may be due to a cultural bias of researchers and/or their research methodologies.

The importance of informally engaging with like-minded individuals or groups has not been indicated in a substantive way in the literature. Ewere et al. (Citation2015) found that social capital factors, including self-employed friends and a personal network, have great significance for women entrepreneurs in townships.

5.3. Research question three

How does each stakeholder relationship enable the female entrepreneur in townships?

The aim of this research question was to understand how the stakeholder relationships in the ecosystem support these entrepreneurs. The responses are tabulated below ().

Table 5. Enablers provided by stakeholders to women entrepreneurs in townships.

As discussed above, families provided the primary point of support for the woman entrepreneurs. Although some families had mixed feelings with regards to entrepreneurship, most provided tangible support in the form of encouragement. Entrepreneurs who achieved some level of success were better able to convince their families to get involved. One interviewee spoke of the added support, advice and contribution she received from staff who viewed the business as their own. However, only in five cases did women feel they could depend on their staff for support. In one case regular clients became friends of the entrepreneur, providing encouragement, praise and referrals. For some, groups of like-minded peers offered comfort, support and advice, as well as the ability to deal with trying times. These groups tend to create social platforms for networking. Community support for the women entrepreneur was often expressed through its purchasing power, leading to a greater level of local sales and onward customer referrals. In some cases, members of the community would provide advice or assistance. One interviewee mentioned that close to 200 women from the community had helped her clear an area of land in order for her to build a crèche on it.

5.4. Research question four

How does each stakeholder group inhibit the female entrepreneur in townships?

The aim of this question was to explore how each of the stakeholder groups hamper the growth of the entrepreneurs. The responses are listed below ().

Table 6. Inhibitors created by stakeholders of women entrepreneurs.

Approximately 55% of the interviewees felt that they did not have the support of the community, which manifested in jealousy, gossip and active discouragement. One interviewee mentioned that ‘in townships, there is this unfortunate thing, we don’t want to see others succeed’. Two interviewees experienced intimidation via aggressive behaviours from the community. One entrepreneur explained that she had faced arrest based on malicious slander, however when she and her business started to win awards, the community wanted to ‘own’ her. Another interviewee believed that a male competitor had been involved in a violent robbery at her premises, while one woman felt that female entrepreneurs were compromised in terms of safety – she had been robbed four times in less than a year. Most entrepreneurs felt that if they did not provide credit to customers, they would be ‘bad-mouthed’ or be discredited in other subtle ways.

The second highest group of stakeholders who were found to inhibit the success of the business were their staff who tend to ‘take advantage’, especially in the theft of products. In other cases, it was more subtle insubordination. One entrepreneur believed that staff would only listen to her husband even though she was the business owner. Interestingly, friends, who are also seen as a high-ranking source of support for the woman entrepreneur, can also be significant inhibitors to business growth by asking for discounts or not wanting to pay for products or services.

Five women spoke of enduring difficulties with unsupportive husbands. One interviewee explained ‘they can’t handle it when their wives are doing too well. They don’t like women who earn more than them’. A consequence of this is emotional abuse through ongoing arguments and derogatory language. Previous research found that a key determinant of whether a spouse had a positive impact on the business was whether he was ‘willing to accommodate the changes required by the wife’s business’, as opposed to being resentful or competitive (Nikina et al., Citation2013). This study reinforces the literature on the impact of spouses and the extended family on the woman entrepreneur, with both groups having the potential to be equally positive or negative for an entrepreneur’s growth (Mordi et al., Citation2010; Nikina et al., Citation2013).

5.5. An integrated model of the stakeholder ecosystem

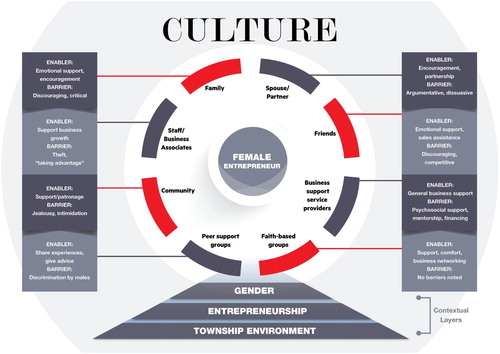

This research shows that women entrepreneurs in the complex contexts of low-income environments in South African townships face psychosocial challenges from a range of stakeholder relationships, which must be understood and addressed by them personally and by support providers to enable them to grow. In line with Welter (Citation2011), this study shows the value that a contextual lens has to frame entrepreneurship by paying attention to the impact of aspects at one level of the phenomenon on aspects of other levels. It also demonstrates the critical importance of a more feminist representation of the lived experience of female entrepreneurship (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2012; Ekinsmyth, Citation2013), as it does not imitate the male norm.

As no empirical research could be found on the enablers and inhibitors that a range of stakeholders provide for women entrepreneurs in low income settings, a model, shown in , was developed. This model shows the importance and complexity of the context in which women entrepreneurs operate, and highlights that culture, particularly around women’s roles in society, serves as the primary influence on the ecosystem in which female entrepreneurs operate. The three added contextual layers of complexity that are discussed above are shown at the base of the model.

Gender-related sensitivities were prevalent with almost all participants. An important outcome of the gender filter is a lack of self-confidence and a belief that the image of successful entrepreneurship is ‘male’. The risk aversion and ‘fear of failure’ related to entrepreneurship as a career often makes it less palatable for the family and community to accept. The township environment manifests in various ways that inhibit woman entrepreneurs’ growth. These three factors thus illustrate how intertwined the business, social and spatial spheres are (Welter, Citation2011).

The components of the stakeholder ecosystem are portrayed along with their experienced ability to either assist or restrict the women’s entrepreneurial success. This aligns with Welter’s (Citation2011) contention that context simultaneously provides opportunities to entrepreneurs and sets boundaries for their actions. The model illustrates the socio-spatial embeddedness (Welter, Citation2011) of women entrepreneurship in townships. The model confirms and further develops an in-depth understanding of the components of the ecosystem for the woman entrepreneurs in townships (Mordi et al., Citation2010; Nikina et al., Citation2013; Ewere et al., Citation2015; Jabeen et al., Citation2015). A unique component that was added to the literature based on the research findings was the importance of faith-based groups as a support structure for these women. These findings illustrate the complexity in contextualising women entrepreneurship by linking social, institutional, historical, spatial or geographical contexts of contemporary South African townships.

6. Recommendations and conclusion

This study shows that women entrepreneurs in townships may be hampered by a deeply-embedded context of integrated psychological and social issues, and thus contributes to the advancement of an understanding of the multi-faceted entrepreneurial phenomenon (De Vita et al., Citation2014). Female business owners in the informal economy are important for economic growth and job creation, yet despite women having run businesses in townships for decades, there has been a dearth of research into the factors affecting their success. The introduction of faith-based groups as a key stakeholder of support to the woman entrepreneur is a further contribution to the literature, which policy makers and support organisations should take into account in their offerings.

Entrepreneurial support could also play a vital role in improving attitudes towards an entrepreneurial career (Malebana, Citation2017), thus service providers need to recognise the particular needs of women entrepreneurs as shown in the model above, and customise psychosocial support that enables women to attain the personality traits that have been identified for successful entrepreneurship (Mordi et al., Citation2010).

Extending this research to other African countries could assist in understanding how the stakeholder ecosystem’s enablers and barriers vary across different countries on the continent. These studies would contribute to bringing richness of context to research on women entrepreneurship (Welter, Citation2011). Further, it would be beneficial for more studies to be carried out in the informal business setting in South Africa as it is a major employer, and the relationship with staff in micro-enterprises is yet to be studied. With the recent changes to the scorecards within Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (Department of Trade & Industry, Republic of South Africa, Citation2013) where enterprise development is emphasised, a study on the competencies needed in this field would be of value.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Caren Brenda Scheepers http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4093-9763

References

- Ahl, H & Marlow, S, 2012. Exploring the dynamics of gender, feminism and entrepreneurship: Advancing debate to escape a dead end? Organization 19(5), 543–62.

- Al-Dajani, H & Marlow, S, 2013. Empowerment and entrepreneurship: A theoretical framework. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 19(5), 503–24.

- Ascher, J, 2012. Female entrepreneurship – an appropriate response to gender discrimination. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation 8(4), 97–114.

- Barbasi, E, Sabarwal, S & Terrell, K, 2011. How do female entrepreneurs perform? Evidence from three developing regions. Small Business Economics 37, 417–41. doi: 10.1007/s11187-011-9374-z

- Bradford, WD, 2007. Distinguishing economically from legally formal firms: Targeting business support to entrepreneurs in South Africa’s townships. Journal of Small Business Management 45(1), 94–115.

- Brush, CG & Cooper, SY, 2012. Female entrepreneurship and economic development: An international perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 24(1–2), 1–6.

- Calás, MB, Smircich, L & Bourne, KA, 2009. Extending the boundaries: Reframing “entrepreneurship as social change” through feminist perspectives. Academy of Management Review 34(3), 552–69.

- Chaney, A, 2014. Black female entrepreneurs in post-apartheid South Africa: Achieving female economic empowerment in the formal and informal sectors. Doctoral thesis. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 3641734).

- Chengadu, S & Scheepers, CB, Eds. 2017. Women leadership in emerging markets. Routledge, New York.

- Chiloane, GE & Mayhew, W, 2010. Difficulties encountered by black women entrepreneurs in accessing training from the small enterprise development agency in South Africa. Gender & Behaviour 8(1), 2590–602.

- Chimucheka, T & Mandipaka, F, 2015. Challenges faced by small, medium and micro enterprises in the Nkonkobe municipality. International Business & Economics Research Journal 14(2), 309–16.

- Chirwa, EW, 2008. Effects of gender on the performance of micro and small enterprises in Malawi. Development Southern Africa 25(3), 347–62.

- Department of Trade & Industry, Republic of South Africa, 2013. Broad-based black economic empowerment codes. https://www.thedti.gov.za Accessed 18 April 2018.

- De Vita, L, Mari, M & Pogessi, S, 2014. Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. European Management Journal 32, 451–60.

- Ekinsmyth, C, 2013. Managing the business of everyday life: The roles of space and place in “mumpreneurship”. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 19(5), 525–46.

- Ewere, AD, Adu, EO & Ibrahim, SI, 2015. Strategies adopted by women entrepreneurs to ensure small business success in the Nkonkobe municipality, Eastern Cape. Journal of Economics 6(1), 1–7.

- Ettl, K & Welter, F, 2010. Gender, context and entrepreneurial learning. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 2(2), 108–29. doi:10.1108/17566261011050991.

- Fatoki, O, 2014. The causes of the failure of new small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(20), 922–7.

- Freeman, RE, 1984. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman Inc, Boston, MA.

- Grant, R, 2013. Gendered spaces of informal entrepreneurship in Soweto, South Africa. Urban Geography 34(1), 86–108.

- Herrington, M, Kew, J & Kew, P, 2014. Global entrepreneurship monitor: South African report 2013. Graduate School of Business at the University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC) World Bank Group, 2018. Sub-Saharan Africa, SME Initiatives. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/region__ext_content/regions/sub-saharan+africa/advisory+services/sustainablebusiness/sme_initiatives Accessed 18 April 2018.

- Isenberg, DJ, 2010. How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review 88(6), 40–50.

- Jabeen, F, Katsioloudes, M & Das, SS, 2015. Is family the key? Exploring the motivation and success factors of female Emirati entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 25(4), 375–94.

- Jennings, J & Brush, CG, 2013. Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? The Academy of Management Annals 7(1), 663–715.

- Johns, G, 2006. The essential impact of context on organizational behaviour. Academy of Management Review 31(2), 386–408.

- Jurgens, U, Donaldson, R, Rule, S & Bahr, J, 2013. Townships in South African cities – literature review and research perspectives. Habitat International 39(1), 256–60.

- Kamberidou, I, 2013. Women entrepreneurs: ‘we cannot have change unless we have men in the room’. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2(1), 6–18.

- Kelley, DJ, Brush, CG, Greene, P & Litovsky, Y, 2013. Global entrepreneurship monitor 2012 women’s report. Babson College, Boston, MA.

- Kuada, J, 2009. Gender, social networks, and entrepreneurship in Ghana. Journal of African Business 10(1), 85–103.

- Lester, N, Menguele, F, Karuri-Sebina, G & Kruger, M, 2009. Township transformation timeline. Department of Co-operative Governance. http://sacitiesnetwork.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/township_transformation_timeline.pdf Accessed 21 August 2019.

- Ligthelm, A, 2011. Survival analysis of small informal businesses in South Africa, 2007–2010. European Business Review 1(2), 160–79.

- Malebana, MJ, 2017. Knowledge of entrepreneurial support and entrepreneurial intention in the rural provinces of South Africa. Development Southern Africa 34(1), 74–89.

- Maphalla, ST, Nieuwenhuizen, C & Roberts, R, 2009. Perceived barriers experienced by township small-, micro-, and medium enterprise entrepreneurs in Mamelodi. Doctoral dissertation, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

- Mattaini, MA & Meyer, CH, 2002. The ecosystems perspective: Implications for practice. In Mattaini, MA, Lowery, CT & Meyer, CH (Eds.), Foundations of social work practice: A graduate text. National Association of Social Workers, Washington, DC, 16–27.

- Mbonyane, B & Ladzani, W, 2011. Factors that hinder the growth of small businesses in South African townships. European Business Review 23(6), 550–60.

- Mordi, C, Simpson, R, Singh, S & Okafor, C, 2010. The role of cultural values in understanding the challenges faced by female entrepreneurs in Nigeria. Gender in Management: An International Journal 25(1), 5–21.

- Nikina, A, Shelton, LM & le Loarne, S, 2013. Does he have her back? A look at how husbands support women entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial Practice Review 2(4), 17–35.

- Njiro, E, Mazwai, T & Urban, B, 2010. A situational analysis of small businesses and enterprises in the townships of the Gauteng province of South Africa. Paper presented at the First International Conference, January, University of Johannesburg, Soweto.

- Nmadu, TM, 2011. Enhancing women’s participation in formal and informal sectors of Nigeria’s economy through entrepreneurship literacy. Journal of Business Diversity 11(1), 87–98.

- O’Neill, RC & Viljoen, L, 2001. Support for female entrepreneurs in South Africa: Improvement or decline? Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences 29(1), 37–44.

- Preisendorfer, P, Bitz, A & Bezuidenhout, FJ, 2012. Black entrepreneurship: A case study on entrepreneurial activities and ambitions in a South African township. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 8(3), 162–79.

- Preisendorfer, P, Perks, S & Bezuidenhout, FJ, 2014. Do South African townships lack entrepreneurial spirit? International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 22(2), 159–78.

- Psychosocial [Def. 2], 2015. Oxford dictionary online. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com Accessed 23 April 2015.

- Rabbani, G & Chowdhury, MS, 2013. Policies and institutional support for women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh: Achievements and challenges. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 2(1), 31–9.

- Rauch, A & Frese, M, 2007. ‘Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurial research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success’. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 16(4), 353–85.

- Saunders, M & Lewis, P, 2012. Doing research in business & management. 1st ed. Pearson Education Limited, Essex, England.

- SBP, 2013. SME growth index. 3rd edn. www.smegrowthindex.co.za Accessed 8 April 2018.

- Schindehutte, M, Morris, M & Brennan, C, 2003. Entrepreneurs and motherhood: Impacts on their children in South Africa and the United States. Journal of Small Business Management 41(1), 94–107.

- Seeletse, SM, 2012. Common causes of small businesses failure in the townships of west rand district municipality in the Gauteng province of South Africa. African Journal of Business Management 6(44), 10994–1002.

- Sharma, KL, 2014. Women entrepreneurship in India: Issues and challenges. International Journal of Entrepreneurship & Business Environment Perspectives 3(4), 1406–11.

- Shelby Rosette, A, Zhou Koval, C, Ma, A & Livingston, RW, 2016. Race matters for women leaders: Intersectional effects on agentic deficiencies and penalties. The Leadership Quarterly 27, 429–45.

- Statistics South Africa, 2018, August. Study of the labour market Q1 2018. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=11129 Accessed 21 August 2019.

- Storey, DJ, 2011. Optimism and chance: The elephants in the entrepreneurship room. International Small Business Journal 29(3), 275–305.

- Treharne Africa Management Services, 2011. Study into women entrepreneurs in townships. Unpublished report, Gordon Institute of Business Science, Johannesburg.

- Welter, F, 2011. Contextualizing entrepreneurship – conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00427.x.

- Witbooi, M & Ukpere, W, 2011. Indigenous female entrepreneurship: Analytical study on access to finance for women entrepreneurs in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management 5(14), 5646–57.

- World Bank-Goldman Sachs, 2008. Women hold up half the sky (Global Economics Paper No. 164). http://www.goldmansachs.com/citizenship/10000women/about-the-program/index.html Accessed 21 August 2019 .