ABSTRACT

Assessing the social impact of tourism-related activities is of paramount importance to promoting sustainable development. The present study aimed to assess the social impact of a project in Cabo Delgado (MZ), designed to increase local community residents’ employability in the emerging tourism sector through the delivery of vocational training programmes, utilising a multi-phase and mixed-method design. The study comprised three different phases (before, during, and after the intervention) and took into account the perspective of a variety of stakeholders. Programmes were perceived to be effective by local operators in the tourism sector and trainees, as they enhanced their living conditions and increased their employability. International operators and tourists, however, had not yet perceived their effectiveness. This study offers a methodological framework for social impact assessment by performing a programme evaluation as an integral part of the intervention itself. This methodology can be extended to other non-tourism related contexts.

1. Introduction

Tourism has been long regarded as an industry which can successfully foster economic and human development (UNCTAD, Citation2008; Rogerson, Citation2013), as well as alleviate rural poverty in developing countries. Indubitably, tourism can provide considerable economic benefits to a country, such as investment opportunities, tax revenue, and development of small and medium enterprises (Choi & Sirakaya, Citation2005; Dyer et al., Citation2007). Although there are different types of revenue generated by the tourism industry, the mere fact that tourism takes place in a developing country does not imply that the money will trickle down to the poor (Saayman et al., Citation2012). Deliberate action is required to make sure that economic benefits reach local communities and have a positive social impact (e.g. in terms of employment opportunities, access to education, and improved standards of living and health). In other words, careful planning is needed both in the delivery of tourism-related activities and in the assessment of their impact. Only in this way can tourism be sustainable and promote the common good at a societal level (Castiglioni et al., Citation2018; Castiglioni et al., Citation2019).

The present paper aims to show how a multi-phase and mixed-method study – performed at different times and with a variety of methodologies and stakeholders – can be a useful tool in assessing the social impact of this kind of tourism-related activity. Specifically, the monitoring and evaluation of the project ‘Profissão Turismo - Vocational training and educational programmes to increase employability in the hotel and tourism sector in Cabo Delgado Province’ will be illustrated. This project aimed to make sure that local communities would directly benefit from the emerging tourism industry in Cabo Delgado Province (MZ) by increasing residents’ employability and enhancing their living conditions. In fact, according to the project document, its general objectives were: to align vocational training for local people with the needs of the emerging tourism sector; to contribute to reducing vulnerable groups’ disparities in access to education; and to promote economic and social sustainability in tourism. Vocational education and training (VET) is considered by development experts to be a specific human capital development instrument that can be effective in promoting socioeconomic progress. Investments in VET are viewed as an approach to increasing economic competitiveness and reducing poverty in the triangle of productivity, employability and sustainable growth (Wallenborn, Citation2010). The potential of VET as an approach to human capital development within African emerging markets is well documented in extant literature (e.g. Atari & McKague, Citation2015). As the African Union (Citation2007:27) noted, the primary objective of all VET programmes should be ‘the acquisition of relevant knowledge, practical skills and attitudes for gainful employment in a particular trade or occupational area’. In the project ‘Profissão Turismo’, the specific trade and occupational area is the emerging tourism sector. To monitor the effectiveness of such a project and its relative activities, relying on economic indicators appeared to be insufficient. Other indicators specifically aimed at monitoring the social impact of the project were necessary.

Before describing the methodology used to conduct this assessment, a brief overview of extant literature on assessment of the social impact of tourism-linked activities and a brief introduction to Mozambique’s tourism development opportunities will be provided.

1.1. Measuring the sustainability and social impact of tourism-linked activities

Sustainable tourism should lead to ‘the management of all resources in such a way that economic, social and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity and life support systems’ (UNWTO, Citation1998:102). Accordingly, assessment of the impact and effectiveness of sustainable tourism-linked activities should consider a variety of indicators, not only economic but also social in nature. According to SIA Guidelines, social impact assessment comprises ‘the processes of analysing, monitoring and managing the intended and unintended social consequences, both positive and negative, of planned interventions and any social change processes invoked by those interventions’ (Vanclay, Citation2003:6). This kind of assessment poses some difficulties, as any given list of social indicators may not capture most of the potential social impact that is likely to occur across a range of planned interventions. Variables that are important should be locally defined, and there may be local considerations that a generic listing does not adequately represent. That is why, in our monitoring activity, we performed a preliminary assessment of local needs and priorities, in order to fine-tune the intervention and its evaluation.

As mentioned above, tourism can contribute to poverty alleviation and provide benefits to local communities in many different ways (Carbone, Citation2005; Scheyvens, Citation2007), for example by increasing individual wages through employment; improving roads, water and infrastructure; increasing levels of education and health; and protecting the environment. To date, most studies on the impact of tourism have focussed on its tangible impacts, such as economic contributions, job creation, and infrastructure development (e.g. Lapeyre, Citation2010; Muganda et al., Citation2010; Saarinen, Citation2010). However, these tangible impacts do not necessarily filter down to the community level (Kuvan & Akan, Citation2005). In other words, objective and tangible achievements are not necessarily perceived as such by members of local communities and, therefore, do not necessary lead to sustainable tourism. Some recent studies revealed the importance of also focussing on intangible influences, which play a significant role in fostering residents’ support for the tourism industry (Scholtz & Slabbert, Citation2018). If local residents do not subjectively perceive significant benefits from the tourism industry, this may undermine their goodwill and support for the industry itself (Kuvan & Akan, Citation2005; Park et al., Citation2012). Ensuring that employment within tourism is expanded and that locals are given priority in employment can increase residents’ satisfaction (Ngowi & Jani, Citation2018).Footnote1 These studies, however, mostly take into account how residents’ perceptions can affect the development of the tourism industry itself, rather than assessing the impact of the tourism industry on local communities’ living conditions. Moreover, a focus on sub-Saharan African countries is still missing in extant literature (Chiutsi & Saarinen, Citation2017).

Based on this premise, the aim of this article is to present a more comprehensive way to assess the impact and the level of sustainability of tourism-linked activities in a southern African region, by also taking into account residents’ perception.

1.2. Mozambique’s tourism development opportunities

Currently, Mozambique has great potential for substantial renewal and growth of the tourism sector. The recent discovery of coal and gas has increased the presence of both regional and international business interests, and tourism has become an increasingly popular component of the development strategy in the country. Tourism development is also the most promising opportunity for economic, social and cultural development for local people in the province of Cabo Delgado (PARP, Citation2011-Citation2014), as the capital Pemba, is the main jumping-off point for tourism in nearby Quirimbas National Park.

By considering both the extant literature on the social impact of tourism-linked activities and the scant evidence regarding their impact in Mozambique and the region of Cabo Delgado, a new social impact framework appears to be necessary. The present study will illustrate an attempt to assess such social impact for the Profissão Turismo project by performing a multi-phase and mixed-method study specifically aimed at capturing local specificities and keeping into account multiple stakeholders’ perspectives.

2. The study: objectives and methodology

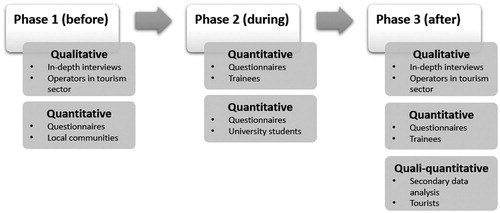

A study was conducted to orient, monitor and evaluate the social impact of the ‘Profissão Turismo project. The study was divided into three different phases that were conducted at different times and with different objectives (see ).

The first phase took place in 2013, before the implementation of the VET programmes. It allowed the identification of emerging training needs and supported the alignment of such programmes with the requirements of the tourism labour market in the province. It consisted of both a qualitative and a quantitative research step. At the qualitative level, local and international operators in the tourism field were interviewed to develop highly tailored and context-based training programmes (see Castiglioni et al. Citation2017). At the quantitative level, a sample of the target groups was interviewed to verify local community residents’ interest in improving their employment opportunities in the tourism sector. The importance of community involvement in planning and managing tourism development has been emphasised in the extant literature (Ashley & Roe, Citation2002; Rogerson, Citation2002; Sebele, Citation2010). People who are involved in tourism activities have a better perception of its socioeconomic impacts than people who are not. The higher the level of community involvement – even at such preliminary stages – the greater the benefits and the greater the promotion of real, sustainable tourism. Results of both the qualitative and the quantitative steps led to the implementation of different tailored vocational training programmes and a University course in Tourism Management.

The second phase of the study took place during the delivery of the VET programmes (between 2014 and 2015). It consisted of quantitative monitoring of the perceived quality of the first editions of the courses and evaluated participants’ satisfaction in order to fine-tune them and improve their effectiveness in terms of acquisition of professional skills. Questionnaires were submitted to both participants in the vocational training programmes and students in the University course.

The third and final phase took place at the end of 2016 and was designed to evaluate the social impact of the training programmes and to perform an overall assessment of the project. It consisted of three different qualitative and quantitative phases in order to take into account the perspective of different stakeholders and have a more comprehensive account. The first qualitative step consisted of interviews with local and international operators in the tourism sector to enable comparison of the results with those from the first phase three years earlier and detect any perceived change from their perspective. The second step consisted of a quantitative study with a sample of participants that completed the vocational training programmes, in order to detect any perceived improvement in their life and living condition. The third and last step was a combined qualitative-quantitative study based on a lexicographic analysis of online reviews to assess tourists’ satisfaction.

It should be noted that, overall, the study considered several stakeholders’ views. That is because the success and effectiveness of a project aimed at increasing the employability of local community residents in the emerging tourism sector depends on a multitude of factors and stakeholders. As previously mentioned, local residents’ perspective is of paramount importance, as their perception makes the difference in terms of promoting sustainable tourism. Nonetheless, local and international operators in the tourism industry are in the unique position of revealing context-specific issues, which are fundamental to fine-tuning and delivering educational and training programmes. At the same time, they are also partially responsible for the success of the project (for example, being the future employers of local residents or being the tour operators that will bring tourists to this destination). Finally, the tourism industry cannot live without tourists: their point of view can be important as well, since the quality of their experience can affect the growth of this sector and the economic development of the country.

3. Results

The results will be divided into three main sections. Given that the qualitative results from the first phase are extensively presented in a previous paper (see Castiglioni et al., Citation2017), more space will be given to the second and third phase. Final considerations and operative suggestions concerning the methodology and assessment of the social impact of this project will be provided too.

3.1. First phase: identification of training needs

The first phase was necessary to understand how to effectively develop highly tailored and context-based training programmes by taking into account context-related characteristics. On one hand, such characteristics included labour market features and needs, which operators in the tourism industry were in a better position to reveal (see qualitative step). On the other hand, they included the level of interest of local community members in being part of this project (see quantitative step).

The qualitative step involved interviews with 34 local and foreign operators in the tourism field (e.g. tour operators, tourist agencies, hotel and restaurant owners, etc.). They were selected based on their ability to reveal which skills would have been necessary to increase local community residents’ employability in the tourism sector (e.g. being their future employers). For reasons of brevity, we only report here a short summary of the key findings (for more details, see Castiglioni et al., Citation2017). Local and foreign employers expressed their reluctance to hire a local workforce given their lack of skills: from minimally-educated local people lacking basic skills essential to working in tourist facilities to high-educated people for managerial positions. The interviewees suggested that the courses, especially those targeted at local people with little education, should be made as concrete and realistic as possible by including a practical experience component (i.e. an internship). Interviewees also emphasised the importance of delivering training programmes not only based on the transfer of technical skills, but also aimed at developing a ‘tourism culture’ by promoting a more favourable attitude among local residents toward paid work, tourism and tourists. It appeared that part of the reluctance of local and foreign employers to hire a local workforce – besides their lack of technical skills – was due to their perceived ambivalent work attitude (e.g. coming late for work; being ‘lazy’, being rude to tourists, etc.), which could be related to a failure to grasp the effective meaning of ‘tourism’ and the benefits that tourism could bring. Thus, raising awareness on this matter and promoting a more favourable cultural attitude towards tourism and tourists appeared to be as important as transferring technical skills.

The second step of this first phase of the study involved local communities and potential beneficiaries of training and educational programmes. In the villages of Pemba and Ibo, where the course would have been implemented, 305 questionnaires were administered to a sample of the target groups. One hundred four secondary school students from Pemba completed a questionnaire and 201 local people aged 18–30 from Pemba and Ibo were administered a face-to-face structured interview, in order to verify their interest in improving their employment opportunities in the tourism sector. Both students and young people from the local communities expressed strong interest in continuing their studies (73% of secondary students) or being trained (96% of local residents) to work in the tourism sector. More than half of secondary students expressed interest in learning to manage a hotel/restaurant (55%), 46% were interested in learning to speak English, and 42% were interested in learning about sustainable tourism. As for local residents, besides improving their knowledge of foreign languages such as English (65%) and Portuguese (32%), they showed great interest in learning about cooking activities (34%) and the hospitality sector (32%).

Taking into account both the results from the qualitative and the quantitative study, the following vocational training programmes were implemented: restaurant and bar services (N = 77 finalists), housekeeping (N = 33 finalists), kitchen service (N = 30 finalists), and tour guides (N = 22 finalists). Several other courses were included, such as English languages courses (N = 76 finalists) and propaedeutic literacy courses (N = 117 finalists), to make the vocational training programme more accessible to illiterate people. Finally, at the Catholic University of Mozambique-Pemba, a degree programme in tourism management was created.

3.2. Second phase: evaluation of the training and educational programmes

The second phase of the study was conducted during the delivery of the VET programmes. Questionnaires were completed by participants at the end of the first edition of the vocational training programsme (N = 108) and at the end of each module of the first university course in tourism management (N = 30). The aim of this phase was to evaluate the programs in order to fine-tune subsequent versions and improve their effectiveness.

The questionnaire for the vocational training programmes was divided into three different sections: ‘course delivery’, ‘contents and didactic materials’, and ‘trainers’. Each item was evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = not satisfied, 5 = very satisfied). In particular, the items ‘Freedom of speech’ and ‘Level of interaction with other classmates’ achieved high scores, thus suggesting the presence of a good climate in the classes, suitable for the development of a positive learning environment (). The high scores of items ‘Value of the contents’ and ‘Importance of the subjects’ suggest that participants were fully aware of the relevance of the contents and subjects in the training programmes (). As for the ‘trainers’ section (), despite the overall high level of satisfaction, the results for the item ‘Trainers are easy to understand’ suggests that there is room for improvement. As stated by participants in an open-ended question, trainers should find easier ways to explain the topics and be more concrete and pragmatic.

Table 1. Percentage of participants who gave a score of 4 or 5 to ‘course delivery’ items (scale from 1 = not satisfied, to 5 = very satisfied).

Table 2. Percentage of participants who gave a score of 4 or 5 to ‘contents and materials’ items (scale from 1 = not satisfied, to 5 = very satisfied).

Table 3. Percentage of participants who gave a score of 4 or 5 to ‘trainers’ items (scale from 1 = not satisfied, to 5 = very satisfied).

Overall, the evaluations of the first versions of the vocational training programmes were very positive. Only minor adjustments appeared to be needed (i.e. trainers were asked to provide contents and examples in a simpler and more concrete way). No relevant differences were found between training programmes delivered in Pemba and Ibo. However, compared to the bar and restaurant service and housekeeping courses, the tour guide training course appeared to have greater room for improvement, as respondents indicated that the contents and examples needed to be made clearer and easier to understand and the value and importance of the subject needed to be better explained. In fact, only 36% and 59% of participants from the first version of the tour guide training course expressed, respectively, high levels of satisfactions for the items ‘Trainers are easy to understand’ and ‘Contents are clear’. It should be noted that this result is in line with evidence from the first phase of the study (see also Castiglioni et al., Citation2017). According to local and foreign operators, local communities may lack a clear understanding of what ‘tourism’ is and what ‘working in tourism’ means. In this regard, the tour guide training course was the most challenging to deliver, as it dealt with some ‘intangible’ aspects of tourism (in contrast to the restaurant and bar service and housekeeping courses, which dealt with more ‘tangible’ aspects). Moreover, the tour guide training course included the subjects of self-employment, entrepreneurship and marketing, which were more complex compared to the subjects covered in the other courses.

Moving to the evaluation of the University programmeFootnote2 in Tourism Management, self-administered questionnaires were completed by 30 students who took part to the first edition. Questionnaires were distributed at the end of each module (see ) and included an open-ended question on the main strengths/weaknesses of the module. The most remarkable result is that students agreed that their completion of each module strongly increased their chances of finding a job both in the tourism sector and in general.

Table 4. Percentage of students who agree that their attendance to the modules increased their chance to work (in tourism sector and in general).

A content analysis of the open-ended questions found that each module had some specificities in terms of learning experience. One of the most challenging modules was ‘Introduction to tourism’, especially in relation to understanding the concept of tourism itself (again, in line with the lack of a concept of ‘tourism’, see Castiglioni et al., Citation2017). Overall, the modules were very appreciated, even the most difficult ones. For example, although it required a lot of individual study and work given the complexity of the subject, the module on ‘Entrepreneurship’ was especially appreciated as it taught students how to develop a business plan. ‘Tourism services’ and ‘Events management’ were the most appreciated modules, especially for their practicality. An indication of their satisfaction is that many students also suggested extending the length of the University programme (e.g. 2 years instead of one; longer modules; etc.).

Overall, for both the vocational training programmes and the University course, participants appeared to be satisfied and aware of the value of receiving this kind of training/education. Only minor adjustments were needed to fine-tune the following versions according to participants’ needs.

3.3. Third phase: impact of the training programmes

The third and last phase of the study was implemented at the end of the training and educational programmes to evaluate their overall effectiveness and social impact. This phase consisted of three different steps, each of them aimed to give voice to a different stakeholder: operators in the tourism industry, local communities, and tourists. The following sections will provide more methodological details and results for each step.

3.3.1. Operators in the tourism sector

In depth interviews with the main operators working at different levels in the tourism sector were conducted to compare the results with those from the first phase of the study and evaluate any perceived change. When feasible, people from the same sample that was selected at the beginning of the study were contacted. Overall, 13 interviews were conducted, out of which six local key informants working in the field of tourism (i.e. two hotel owners, one tour operator, one tourism agent, and two tourism consultants) and seven international tour operators that include Mozambique in their offerings.

According to the local informants, the cultural gap that had been identified at the beginning of the project had been reduced. Before the beginning of the vocational training programmes, they described local workers as lazy, not interested in their work or in improving themselves, and having a poor work ethic. At the end of project, instead, they said they were finally able to hire a local workforce who already had knowledge and skills to work in the tourism sector. Overall, they showed a great appreciation for the educational and training programmes that were implemented.

I hired a waiter who knows how to clean a table. I also hired two women to clean the hotel rooms, and they have notions of hygiene (…) I feel this is not just my experience: other hotel managers are satisfied in the same way. (Local operator)

Please, don’t stop! You need to keep running the training programs. (Local operator)

Both local and international operators recognised the effectiveness of the educational and training programmes in terms of quality of the offer and delivered services.

The cleaning standard in hotels has increased (International operator)

More people now know how to host a tourist (International operator)

In addition, they recognised that the project was effective in including the most vulnerable categories.

I feel that this program offers more opportunities to locals, especially to women. Women are a disadvantaged population because they are illiterate, but thanks to the course, now they can work. (Local operator)

Although the training programmes were appreciated, international operators working in the tourism industry still recognise that there is still a lot of work to do to promote Mozambique and Cabo Delgado as a tourist destination (e.g. addressing the gap between the coastline and inland; price/quality ratio of accommodation; accessibility; tourism management), as increasing residents’ employability represented just a piece of a more complex puzzle. Although it is recognised that tourism in Mozambique is growing (even if at a slow pace), Mozambique is still not a sought-after African destination by tourists. Moreover, some tour operators are still reluctant to suggest Mozambique and Cabo Delgado as a possible holiday destination.

Other places such as Mauritius are preferred to Mozambique. Mauritius or Seychelles are equally beautiful but more promoted and less expensive than Mozambique. (International operator)

Mozambique is not a destination for everybody. I only suggest it to a few clients that appear to have the right characteristics for it. (International operator)

To sum up, the educational and training programmes started a positive change, as witnessed by the lack of formal complaints in terms of finding local people to hire. Nonetheless, increasing the employability of local community residents is just a preliminary step in a more complex journey towards sustainable tourism development.

3.3.2. Local communities

To verify the effectiveness of the project in improving participants’ life conditions, a community development expert submitted a questionnaire to participants both before and afterFootnote3 the delivery of the training programmes. Only questionnaires that were filled in both before and after the training were considered for the analysis. In this way, we could verify whether the training programmes were actually able to make a difference in participants’ life conditions. The questionnaire consisted of five different sections, dealing with both tangible (i.e. socio-economic profile, living conditions, personal properties, working situation) and intangible aspects (i.e. perception of improvement). The final sample consisted of 78 participants (42% females).

One meaningful result was an increase in the employment rate. Whereas only 5% of participants already had a job before starting the programmes, only four/five months after the end of the courses the situation significantly improved: one person out of four was employed (25%).

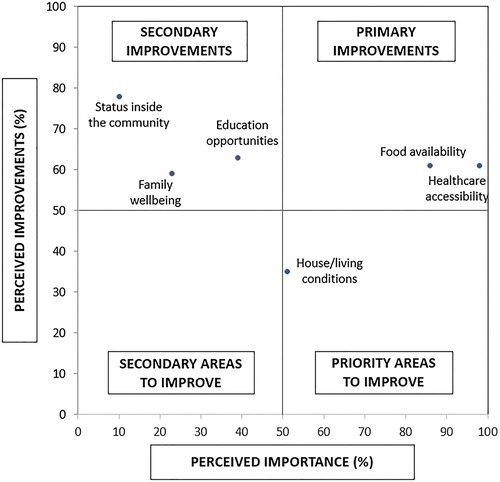

Focusing on the subjectively perceived benefits, participants were asked to state if – after the training – they perceived any improvement in their personal life condition. Different life aspects were evaluated, as participants were invited to express whether the situation had improved, worsened, or remained the same (see ). Participants reported a relevant improvement of their life condition, especially in terms of improving their social status inside their community (78%). The majority also perceived an improvement in education opportunities, healthcare accessibility, food availability, and family wellbeing. Only one out of three (35%) reported an improvement in housing and living conditions. This result is in line with the fact that an improvement in housing and living conditions may not be an immediate benefit gained after the training courses and may require more time.

Table 5. Perception of change in individual life conditions after attending the vocational training programmes.

Participants were also asked to rate the importance of each item in relation to the ability to improve their living conditions. By drawing a graph based on scores of perceived improvements (vertical axis) and perceived importance of each item (horizontal axis), it was possible to identify four different quadrants suggesting the main achievements and the priority areas still requiring improvements (see ).

The top right quadrant identifies the primary improvements (i.e. those aspects that have improved and are also considered as very important), whereas the top left quadrant identifies secondary improvements (i.e. those aspects that have improved but are not considered extremely important). It appears that food availability and healthcare accessibility represent the primary areas of improvement, as they appear to be very important for the general wellbeing and living conditions of participants and have improved for more than half of them. The bottom right quadrant, instead, represents the priority areas needing improvement, as they are important but less than half of participants perceived any improvement. In this quadrant, we find housing/living conditions.

Participants were not only asked about their personal situation after attending the programmes, but they were also asked if they had perceived any significant improvement for the whole community since the start of the Profissão Turismo project (three/four years before). shows that there were consistent improvements in the community situation since the beginning of the project, especially in terms of educational (96%) and work opportunities (85%).

Table 6. Perception of change in life conditions at community level since the beginning of the project Profissão Turismo.

Although an array of other external variables has possibly combined to determine the overall perceived improvement at the community level, this result suggests that participants in the vocational training programmes were able to perceive a positive social impact of the project at both the individual and collective level.

3.3.3. Tourists

Finally, in order to take into account tourists’ perspective and verify whether they witnessed any change in the tourism industry in Cabo Delgado, a combined qualitative-quantitative analysis was performed by retrieving online reviews from tourists who visited Cabo Delgado. Collecting online textual material can be an effective way to assess attitudes towards a specific topic (Lozza & Castiglioni, Citation2018). Textual reviews were collected from Tripadvisor.com between 2015 and 2016 (N = 307),

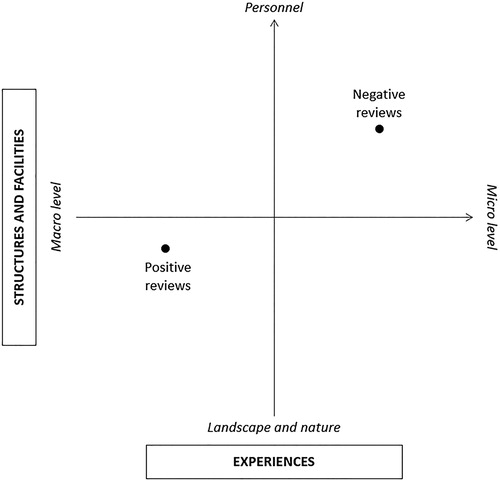

A CAQDAS lexical analysis was then performed using the T-LAB 9.1 software (Lancia, Citation2015) on the open-ended comments. T-LAB is an all-in-one set of linguistic, statistical, and graphical tools for text analysis. T-LAB bases its analysis on occurrences and co-occurrences of lexical units (LU) within the textual corpus or context units (CU), such as sentences, paragraphs, or short documents. We performed a correspondence analysis on the retrieved corpus of open-ended comments, which allows for the drawing of graphs in which the relationships between both the CU and the LU that make them are represented. The analysis yielded two dimensions: factor 1 (horizontal axis, explained inertia = .53) and factor 2 (vertical axis, explained inertia = .52). By analyzing the words that characterised each factorial pole (i.e. the opposites on the horizontal and vertical axes), we were able to identify the underlying main dimensions. The horizontal axis opposes words linked to finding an accommodation (e.g. hotel, place, resort, staying, reservation, vacation, etc.) to words used to describe the facilities of the chosen accommodation (room, toilet, shower, TV, bed, air-conditioning, etc.). We labelled the horizontal axis ‘structures and facilities’, where the left pole focuses on a ‘macro level’ and the right pole on a ‘micro level’. The vertical axis, instead, opposes words linked to the natural landscape (e.g. view, beach, ocean, sea, etc.) to words used to describe the hotel personnel (kind, available, professional, staff, director, etc.). We labelled the vertical axis ‘experiences’, where the upper pole focuses on ‘personnel’ and the bottom pole on ‘landscape and nature’.

As shown in , it appears that positive reviews mostly focus on hotel structure and facilities at the macro level and on the beauty of the surroundings. From tourists’ perspective, however, there is still room for improvement in terms of the service delivered by local personnel and hotels at the micro level, as suggesting by the positioning of the category ‘negative reviews’ in the graph. This perception may be the result of a comparison with the services delivered in other countries with an older tradition and history of a tourism industry, thus confirming the existence of a gap in terms of tourism industry development.

4. Discussion

The present paper illustrated the results of a multi-phase and mixed-methods study aimed at assessing the social impact of the ‘Profissão turismo – Vocational training and educational programmes to increase employability in the hotel and tourism sector in Cabo Delgado Province’ project. The contribution of this work is at least threefold.

First, it expands the limited literature on tourism development in Mozambican territories, by specifically referring to the notion of ‘sustainable tourism development’. Although general attention to sustainability and sustainable tourism development is increasing, not all countries are equally represented in the extant literature. Mozambique as a country has received little attention so far.

Second, it provides an example of how to assess the social impact of an intervention aimed at enhancing the living conditions of local communities, by taking into account not only ‘tangible’ and objectives outcomes, but also ‘intangibles’ and subjectively perceived benefits. In fact, a thorough understanding of local community perceptions of tourism-linked activities is considered to be a means towards sustainable tourism development (Sharpley, Citation2014). For this reasons, local residents’ perspective has been taken into account throughout all phases of the study: at the beginning to verify their interest in this opportunity; during the deployment of the VET programmes, to verify their satisfaction and fine-tune the programmes; and at the end of project, to assess its effectiveness in enhancing their living conditions.

Finally, this study took into account a great variety of stakeholders, including not only local communities but also tourism operators (at the local and international levels) and tourists. As a matter of fact, tourism and its sustainable development is a complex phenomenon and only by taking into account multiple stakeholders’ perspectives can all the different nuances be revealed.

In terms of results, it was found that the ‘Profissão turismo’ project was able to fill one major gap that was detected at the very beginning of the study, the inability of local operators to hire a local workforce in the emerging tourism sector. Local stakeholders (and hotel managers in particular) detected a positive change and showed great appreciation for the vocational training programmes. Overall, participants from the VET programmes showed a high level of satisfaction with both the content and the perceived utility of the programmes. In addition, despite the short period of time that had passed between the end of the courses and the data collection, the programmes proved to be effective in enhancing participants’ life conditions and increasing their employability. Benefits were perceived not only at the individual level, but also at the community level. It should be noted, however, that the social impact of the programme – although perceived at the local level – has not arrived yet at the international level, as suggested by data collected from international tourism operators and tourists. Presumably, it will take longer before the effects of the project reverberate outside local communities. Nonetheless, in line with other studies (see Mafunzwaini & Hugo, Citation2005), education and training at different levels appears to be a promising element of success in tourism development.

The relevance of this kind of intervention is further increased by the recent destruction and humanitarian catastrophe caused in April 2019 by Cyclone Kenneth, one of the strongest tropical cyclones to make landfall in Mozambique. Although at the time of writing no official statistics are available in terms of impact on the demand for the affected tourist areas, the extant literature shows that the reporting of the news on such events has a strong influence on the image which tourists perceive of the threat to their personal security (see also Steiner et al., Citation2006).

One major limitation of this study is the impossibility of controlling for unobserved factors that may have influenced local communities’ perceptions of improvements. An alternative methodological approach to overcoming this limitation would be a randomised control trial design, a methodology that is increasing in popularity even in rural contexts and developing countries (e.g. Raza et al., Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2018). However, clustering participants in homogeneous groups and controlling for an array of external variables poses several challenges outside a laboratory setting. In addition, in order to make this project as inclusive as possible, rather than randomly assigning participants to either the real intervention or a control condition, we offered all people who expressed interest the opportunity to partake in the programme. A further limitation is the limited period that was monitored after the end of the project, due to funding and time constraints. Ideally, further assessment and evaluations should take place in the long term too, to make sure that the positive impact can last. In addition, the present study does not allow generalisation of its results to other contexts. In other words, this kind of intervention may not necessarily be effective elsewhere. Nonetheless, it is indeed its focus on local issues and its context-specificity that allows an in-depth understanding of the social impact of the project. Rather than providing a fixed list of social impact indicators, this paper aimed to provide a methodological mindset that could orient future assessments. The evaluation and social impact of any kind of intervention should not be seen as a completely separate and independent matter. Instead, it should dialogue with the intervention itself from the very beginning to the end. Thus, the methodology behind the assessment of the social impact of this kind of intervention – rather than the intervention itself – can be generalised to other contexts.

In conclusion, the present paper is an example of how a study aimed to assess the social impact of a project can be an integral part of the intervention itself. Although relying on a specific case study of tourism development as a means of poverty alleviation in Cabo Delgado, its methodology can be extended to other contexts, both tourism and non-tourism related.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to local operators from Istituto Oikos who helped us to recruit participants for this study and assisted us in the field. This work was supported by the European Commission under the project title ‘Profissão turismo - Vocational training and educational programs to increase employability in the hotel and tourism sector in Cabo Delgado Province’ (Reference: EuropeAid/131572/L/ACT/MZ).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 According to Social Exchange Theory (SET), which is commonly used in understanding residents’ perception of tourism impacts (Nunkoo et al., Citation2013), the residents offer their support to tourism industry if they perceive positive tourism impacts to outweigh negative impacts.

2 The University course in Tourism Management was one-year long.

3 Four to five months after the end of the programs.

References

- African Union, 2007. Strategy to revitalize technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in Africa. African Union, Addis Ababa.

- Ashley, C & Roe, D, 2002. Making tourism work for the poor: Strategies and challenges in Southern Africa. Development Southern Africa 19(1), 61–82.

- Atari, DO & McKague, K, 2015. South Sudan: Stakeholders’ views of technical and vocational education and training and a framework for action. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 67(2), 169–86.

- Carbone, M, 2005. Sustainable tourism in developing countries: Poverty alleviation, participatory planning, and ethical issues. The European Journal of Development Research 17(3), 559–65. .1.

- Castiglioni, C, Lozza, E, Libreri, C & Anselmi, P, 2017. Increasing employability in the emerging tourism sector in Mozambique: Results of a qualitative study. Development Southern Africa 34(3), 245–59.

- Castiglioni, C, Lozza, E & Bosio, AC, 2018. Lay people Representations on the common good and Its Financial Provision. SAGE Open 8(4), 1–16.

- Castiglioni, C, Lozza, E & Bonanomi, A, 2019. The common good provision scale (CGP): A tool for assessing people’s Orientation towards economic and social sustainability. Sustainability 11(2), 370.

- Chiutsi, S & Saarinen, J, 2017. Local participation in transfrontier tourism: Case of Sengwe community in great limpopo transfrontier conservation area, Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa 34(3), 260–75.

- Choi, HSC & Sirakaya, E, 2005. Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: Development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. Journal of Travel Research 43(4), 380–94.

- Dyer, P, Gursoy, D, Sharma, B & Carter, J, 2007. Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tourism Management 28(2), 409–22.

- Kuvan, Y & Akan, P, 2005. Residents’ attitudes toward general and forest-related impacts of tourism: The case of Belek, Antalya. Tourism Management 26(5), 691–706.

- Lancia, F, 2015. T-LAB 9.1-User’s Manual.

- Lapeyre, R, 2010. Community-based tourism as a sustainable solution to maximise impacts locally? The Tsiseb Conservancy case, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 757–72.

- Lozza, E & Castiglioni, C, 2018. Tax climate in the national press: A new tool in tax behaviour research. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 6(2), 401–19.

- Mafunzwaini, AE & Hugo, L, 2005. Unlocking the rural tourism potential of the Limpopo province of South Africa: Some strategic guidelines. Development Southern Africa 22(2), 251–65.

- Muganda, M, Sahli, M & Smith, KA, 2010. Tourism’s contribution to poverty alleviation: A community perspective from Tanzania. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 629–46.

- Ngowi, RE & Jani, D, 2018. Residents’ perception of tourism and their satisfaction: Evidence from Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Development Southern Africa 35(6), 731–42.

- Nunkoo, R, Smith, SLJ & Ramkissoon, H, 2013. Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A Longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(1), 5–25.

- Park, DB, Lee, KW, Choi, HS & Yoon, Y, 2012. Factors influencing social capital in rural tourism communities in South Korea. Tourism Management 33(6), 1511–20.

- PARP (Action Plan for Reducing Poverty), 2011–14. Preliminary integrated tourism development plan for Cabo Delgado 2007–2013.

- Raza, WA, van de Poel, E, Bedi, A & Rutten, F, 2016. Impact of community-based health insurance on access and financial protection: Evidence from three randomized control trials in rural India. Health Economics 25(6), 675–87.

- Rogerson, CM, 2002. Tourism and local economic development: The case of the Highlands Meander. Development Southern Africa 19(1), 143–67.

- Rogerson, CM, 2013. Urban tourism, economic regeneration and inclusion: Evidence from South Africa. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 28(2), 188–202.

- Saarinen, J, 2010. Local tourism awareness: Community views in Katutura and King Nehale Conservancy, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 713–24.

- Saayman, M, Rossouw, R & Krugell, W, 2012. The impact of tourism on poverty in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 29(3), 462–87.

- Scheyvens, R, 2007. Exploring the tourism-poverty Nexus. Current Issues in Tourism 10(2–3), 231–54.

- Scholtz, M & Slabbert, E, 2018. A remodelled approach to measuring the social impact of tourism in a developing country. Development Southern Africa 35(6), 743–59.

- Sebele, LS, 2010. Community-based tourism ventures, benefits and challenges: Khama Rhino Sanctuary trust, Central District, Botswana. Tourism Management 31(1), 136–46.

- Sharpley, R, 2014. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management 42, 37–49.

- Steiner, C, Al-Hamarneh, A & Meyer, G, 2006. War, terror, catastrophes and their impact on tourist markets. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 50(2), 98–108.

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), 2008. FDI and tourism: The development dimension – East and Southern Africa. United Nations, New York & Geneva.

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organisation), 1998. Guide for local authorities on developing sustainable tourism. UNWTO, Madrid, Spain.

- Vanclay, F, 2003. International principles for social impact assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 21(1), 5–12.

- Wallenborn, M, 2010. Vocational education and training and human capital development: Current practice and future options. European Journal of Education 45(2), 181–98.

- Wang, JSH, Sewamala, FM, Neilands, TB, Bermudez, LG, Garfinkel, I & Waldfogel, J, 2018. Effects of financial incentives on saving outcomes and material well-being: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Uganda. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37(3), 602–29.