ABSTRACT

Rising calls on sustainable practices ignited the need for hotels to develop innovative and sustainable ideas and approached to conserve the environment. This paper examines and discusses the existence and application of innovative sustainable environmental practices within Malawi hotels. Qualitative approaches were adopted to collect the data from public and private actors in the accommodation sub-sector. The Rogers Diffusion of Innovation Theory was used to determine the most prevalent reason for adopting an innovation strategy within some of the hotels in Lilongwe. It is reviewed that to a lesser extent some hotels adopted innovative strategies in water and energy use, waste management and hotel design. The collaborative effort between the government and private sector and the strengthening of the implementation of sustainability policies is recommended to promote environmental sustainability innovation. These views have been discussed within the broader discourse on environmental sustainability and innovations within hotels, in the Sub – Saharan African context.

1. Introduction

In the new global economy, the sub-sectors within the tourism and hospitality industry have become central focal point of debates and discussions because of their contribution to economic growth and national development as well as their environmental impacts through natural resource use and carbon emission (Aragon-Correa et al., Citation2015; Bruns-Smith et al., Citation2015; Carasuk et al., Citation2016). Available evidence suggests that if tourism development, is not well regulated, it can lead to serious natural resource depletion culminating into significant environmental and ecological crisis (Foster, Citation2008). The Marxist Theory of the nineteenth century, as observed by Foster (Citation2013), provides ecological insights to understanding the relationship between tourism development, the ecosystems, and ecological complexity. In this regard, therefore, various economic development disciplines have sought to include ecological awareness into their core paradigm to address challenges that environmentalism has raised in line with the now widely perceived global ecological crisis (Alvarez, Citation2014). It is from this backdrop and supported by empirical evidence from Lilongwe that this paper examines and provides an overview of the relationship between tourism and environmental sustainability. The paper specifically focusses on how some of the innovative practices within the accommodation sector in Lilongwe are either contributing to or hampering environmental sustainability.

The tourism sector in Malawi has become one of the key priority areas for economic growth and national development (see Magombo et al., Citation2017). The accommodation sub-sector in Lilongwe, for example, has demonstrated steady growth since the advent of the multi-party system of government in 1994 (Nsiku & Kiratu, Citation2009; Bello et al., Citation2017; Magombo et al., Citation2017). At around the same time, there was a global justifiable growing concern with undesirable accelerated changes to the environment by various development activities including developments within the tourism sector, which increased environmental degradation through processes such as air and water pollution (Hulse, Citation2007; Booyens, Citation2012; Smith & Leonard, Citation2018).

Within the broader discourse of tourism and environmental sustainability, available evidence suggests that a number of scholars from more economically developed countries have discussed some of the efforts which the accommodation sub-sector has made in trying to address the perceived ecological crisis (Bohdanowicz et al., Citation2011; Cvelbar & Dwyer, Citation2013; Aragon-Correa et al., Citation2015). These scholars have attempted to demonstrate that the accommodation sub-sector in these developed countries has adopted and implemented several innovative strategies aimed at addressing this widely known global ecological crisis (Bruns-Smith et al., Citation2015; Carasuk et al., Citation2016; Warren et al., Citation2017). These innovations have mainly targeted natural resource (Water, Energy and other raw materials) usage by promoting best practices which foster environmental sustainability (Bohdanowicz et al., Citation2011; Cvelbar & Dwyer, Citation2013; Aragon-Correa et al., Citation2015).

Recent studies from the developing countries, especially those focusing on the Sub – Saharan African region, have also shown that some accommodation units have started adopting environmental sustainability innovations in their bid to reduce and minimise their ecological footprint and promote best environmental and sustainability practices (Merwe & Wöcke, Citation2007; Rogerson & Sims, Citation2012; Booyens & Rodgerson, Citation2016; Musavengane, Citation2019). Related to this development, there are some studies (including the current study), which have been conducted to understand how institutions adopt innovations using the Diffusion of Innovation Theory developed by Rodger in 1962 (Murray, Citation2009; Dibra, Citation2015; Hang et al., Citation2016).

A rapid and in-depth appraisal and review of existing literature in the context of Malawi has revealed a lack of and/or limited availability of discussions on topics of a similar nature, particularly in the accommodation sub-sector (Nsiku & Kiratu, Citation2009; Magombo & Rogerson, Citation2012; Bello et al., Citation2017). Evidence available suggests that existing literature has mainly focused issues relating to understanding the overall contribution of tourism to social and economic development and not on examining the environmental sustainability initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable tourism development (STD) and sustainable economic development (SED) (Nsiku & Kiratu, Citation2009; Magombo & Rogerson, Citation2012; Bello et al., Citation2017). Thus, it would not be an exaggeration to argue that the current study/paper is among the first of its nature to address issues of environmental sustainability and innovations in the accommodation sub-sector and Malawi.

2. The Rodgers diffusion of innovation

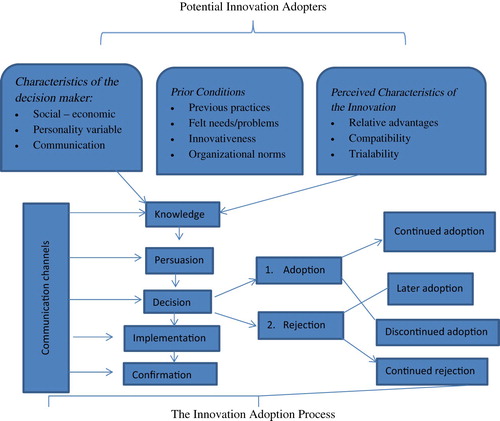

This theory stipulates that there are many forms of information about an innovation that can influence the adoption process of innovation. Hang et al. (Citation2016) argue that there are two sets of information that influences the adoption process, thus awareness information and cost–benefit information. However, Murray (Citation2009) is of the view that there are five primary factors (see ) which would interest an organisation to adopt an innovation and these are; the perceived relative advantage over previous practices; the ease of comprehension; compatibility with the adopter’s values and needs; testability and result visibility. Dibra (Citation2015) also confirm that these factors have been instrumental in the innovation adoption processes in most hotels.

Figure 1. Elements of Rogers initial model of innovation diffusion process. Source: Dibra (Citation2015).

3. The impact of the accommodation sector on the environment

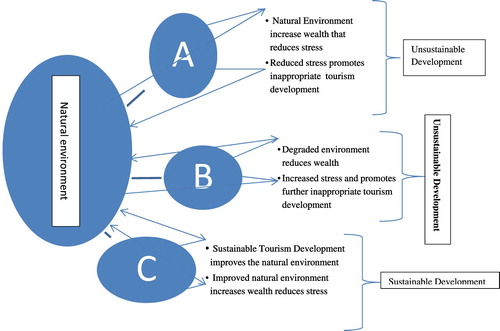

In recent years, there has been an increasing amount of literature on the intense utilisation of natural resources, whereby the hotels’ environmental carbon footprint is typically larger than those of buildings of similar size, but are under a different use (Aragon-Correa et al., Citation2015; Mohapatra, Citation2016; Warren et al., Citation2017). It has been argued that these units irrespective of the size have to find ways of reducing their carbon footprint (Berezan et al., Citation2013; Claver-Cortés et al., Citation2015). According to Middleton (Citation2013), the disruption to the natural environment caused by lodging facilities ultimately feeds back on the operations of the facility itself and the society’s general wellbeing. Given what has been said so far, one may suppose that the operations within the accommodation sub-sector ought to conform more closely with that of the ecosystem otherwise, the sector may destroy itself (Carasuk et al., Citation2016). compares the three cycles showing the relationship between modes of development and the environment. Cycle A, represents the global economy in historical times where wealth was accumulated largely by degrading the environment. This wealth brought numerous advances to most parts of the world, which reduced stress on the society improved livelihoods prompting further inappropriate development to continue on cycle A (Middleton, Citation2013). As noted by Alvarez (Citation2014) when the economic developments in cycle A, cross an environmental threshold and the developments enter cycle B, the degraded environment begins to feedback on society’s livelihoods and stress increases. According to Houdre’ (Citation2011), the increased stress on livelihoods in cycle B promotes further inappropriate economic developments in a country particularly when the country in question has limited livelihood options. Therefore, any continued economic developments in cycle B would ultimately lead to society’s livelihood collapse. Questions have been raised about rapid developments experienced within the tourism sector in Malawi after 1994 in line with the corresponding negative impact on the natural environment. The only appropriate way to exit cycle B is to enter cycle C by adjusting the tourism sector development system from being parasitic to the environment to a more symbiotic one (Middleton, Citation2013). A recent study by Aragon-Correa et al. (Citation2015) suggests that cycle C is the idle long-term economic development strategy despite a danger that reduced stress would encourage a reversion to the old ways of cycles A and B.

Figure 2. The three cycles showing the relationship between modes of development and the natural environment. Source: Modified from Middleton (Citation2013).

Recent evidence suggests that the accommodation units consume huge amounts of water and energy to sustain their operations compared to similar domestic operations that demand the same resources (Bohdanowicz et al., Citation2011). Indicatively, Kasim (Citation2007) summarised the estimated water consumption levels () within the accommodation units of different sizes which suggests that these facilities could negatively impact the environment they ignore water sustainability innovations. There is a consensus among researchers that these units also consume a lot of energy which creates pressure on various energy sources (Bohdanowicz et al., Citation2011; Government of Malawi, Citation2017; Chan & Hawkins, Citation2010; Goldstein et al., Citation2012). For example, Goldstein et al. (Citation2012) suggests that a luxury accommodation units in tropical climatic locations consume around 280 kWh/m2 per year whilst a similar facility operating in temperate climatic locations consumes about 200 kWh/m2 per year. Recent evidence from Malawi suggests that there is an increase in energy demand that supply such that accommodation units have resorted to using fuelwood which has increased environmental degradation (Mwale et al., Citation2013).

Table 1. Estimated average monthly hotel water consumption.

Available evidence suggests that volumes of waste that are produced by the accommodation units are one of the major causes of environmental-related catastrophe affecting livelihoods (Middleton, Citation2013; Bruns-Smith et al., Citation2015; Wanda et al., Citation2017). For instance, Wanda et al. (Citation2017) discovered that personal care waste products discharged into the environment from accommodation units contains micropollutants which comprise of a wide range of natural and synthetic organic compounds which are contaminants of emerging concern. A recent study by Nsiku & Kiratu (Citation2009) suggested that in Malawi accommodation units generate waste materials that are carelessly released into the environment.

4. Innovations within the accommodation sector

There is a large volume of published studies describing the efforts that the accommodation units are making in promoting sustainable consumption and production practices focusing on energy, water, and other consumables (Legrand et al., Citation2013; Kasim et al., Citation2014; Fraj et al., Citation2015). Most of the efforts being pursued within these units are through the adoption of innovations (Priego et al., Citation2011). It is from this approach that innovations of various forms have been made to try to address environmental challenges facing mankind ().

Figure 3. Kumbali Country Lodge built with locally sourced materials. Source: https://www.tripadvisor.com. Accessed 14 August 2018.

Over the past decade most research in sustainability innovations within the accommodation units has emphasised that a diversity of small operations from food and beverage operations to housekeeping, each of these accounts for a small share of environmental pollution in terms of energy and water consumption, food waste and other resources (Kasim et al., Citation2014; Booyens & Rodgerson, Citation2016; Kuščer et al., Citation2017). Due to mounting pressure from other stakeholders, this sub-sector started innovations to modify their operating procedures without compromising customer experience and service quality in the late 1980s (Bisgaard et al., Citation2012; Aragon-Correa et al., Citation2015; Borden et al., Citation2017).

Recent studies suggest that some hotels became innovative by reusing, recovering, and recycling waste products to minimise their impact on the natural environment (Radwan et al., Citation2012; Rodríguez-Antón et al., Citation2012; Razumova et al., Citation2015). These hotels innovated a waste treatment techniques hierarchy () to reduce the amount of waste they produce (Middleton, Citation2013). Reusing a waste product in a hotel makes environmental sense as opposed to discarding it into the environment because it reduces resource consumption (Alvarez, Citation2014). Global hotel chains innovated toolkits such as the Hotel Energy Solution launched in 2011 and the Nearly Zero Energy Hotel launched in 2013 (Legrand et al., Citation2013). These hotels replaced incandescent bulbs with Compact Fluorescent Lamp’s (CFL’s) or Light-emitting Diode (LED) bulbs to reduce energy consumption and environmental impacts (Doherty, Citation2013). Rathore et al. (Citation2009) draws our attention to distinctive specifications of the Green Building Council and states that most modern accommodation units succeed in becoming sustainable by achieving the leadership in energy and environmental design certification (LEED). Most chain hotels have adopted online booking systems and encourage their guest to book via such systems to reduce paper usage (Berezan et al., Citation2013). Similarly, Goldstein et al. (Citation2012) noted that in these facilities they have also adopted computer network systems that allow employees to transact and communicate business matters with minimal paper usage. Studies that have been carried out so far on the sustainable tourism in Malawi have not conclusively dealt with such developments and as such this study attempted to address this gap.

Table 2. Waste management hierarchy: priorities for treatment.

5. Methodological considerations

This paper adopted Grounded Theory (GT) both as a methodological and analytical framework as it provides an effective and systematic inductive way of constructing a theory on innovative environmental sustainability in the accommodation units of Lilongwe (Charmaz, Citation2006). There are two schools of thought within the GT – the Glaser and Strauss thoughts. The Glaser model emphasises on inductive approach whilst the Strauss model provides room for a deductive approach (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998; Glaser, Citation2016). In this regard, therefore, the Strauss model was used in this article as we adopted the deductive approach.

The sample for this study comprised (see and ) a total of twenty-four (24) respondents. The first five (5) respondents were purposefully selected from five (5) key government departments that are directly responsible for regulating the operations within the tourism industry in general and hotels specifically (Bernard, Citation2006). Eligibility criteria required individuals to have been working in these government departments inspecting hotels in terms of policy, regulation, and practice. The study also purposefully recruited respondents who were in charge of various specific hotel operations from six (6) star graded hotels. Through Convenience Sampling, eleven (11) other supervisors were also recruited as Key Informants (Glaser, Citation1992). Two Focus Group Discussion (FGDs) were conducted in one 4-star, and two 2-star hotels.

Table 3. Profile of the respondents from government departments.

Table 4. Profile of respondents from accommodation units.

Key Informant Interviews and FGDs, and field visits where photographs were taken to gather data for this study (Charmaz, Citation2006). This data was collected from September to December 2017. The interview guide comprised of open-ended questions and where clarity was sought, follow – up closed-ended questions were used in the course of the interview process (Cilliérs et al., Citation2014). Permission was sought to use pictures and other information available on their websites deemed helpful to provide answers to the research objectives (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990). Follow up telephone interviews were done to solicit extra views from the respondents on matters arising from the preliminary data analysis process (Charmaz, Citation2006).

After the interviews were transcribed verbatim, each transcript was assigned a code and each respondent was given a pseudonym to conceal their identity (Charmaz, Citation1996). Thereafter, each line of every transcript was assigned a line number to facilitate a line by line analysis (Bernard, Citation2006). Through this process, smaller categories of meaning from the data were prepared (Charmaz, Citation2006). These smaller categories were further scrutinised to identify similarities and differences and later those smaller categories that represented a generally similar meaning were combine to form subcategories which were representing the general interpretation of data per each transcript (Bernard, Citation2006). These subcategories were also scrutinised, compared with other subcategories from other transcripts and those subcategories with similar interpretation were combined to form major categories and final themes emanating from data from different interview transcripts (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998; Merriam, Citation2009).

The pictorial evidence collected during fieldwork and from various websites, were critically analysed in line with information generated from the interview transcripts and for purposes of triangulation and validation of the research findings (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998; Bernard, Citation2006; Charmaz, Citation2006; Willig, Citation2008; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2011). Furthermore, direct quotations and the photographs have also been used for purposes of illustrating and clarifying the discussion under consideration.

6. Results and discussion

The first set of results presents the perceptions of the regulating and policing authorities of the accommodation units in Lilongwe. Three respondents from the public sector provided their opinion whilst the other two indicated they had dealt with these units before. Two broad themes emerged from the data analysis (Non-Compliance and Conservation Efforts) from the public sector (from the Department of Tourism, Department of Environmental Affairs and City Assembly). Talking about the issues of non – compliance Officer A, said: ‘There is a tendency in Malawi for some hotel developers just cut down all the trees, which is a very bad practice because tourism strives on nature.’ Officer B said: ‘In fact, I would say the hotel sector is one area that we (department of environmental affairs) have a big challenge within terms of compliance.’ Officer C also said: ‘for example, we have got this hotel close to us here (Sunbird Capital Hotel). There is always bad smells there because of some problems with their sewer line’. A possible explanation for these perceptions could probably be based on the inability by Sunbird Hotel to conduct routine maintenance of the sewer system. As a result, the smell that comes from the hotel’s sewer system pollutes the air.

The second set of analysis examined the practices within the selected accommodation units in Lilongwe. The following thematic areas emerged from the data analysis from the accommodation sub-sector; Water Conservation, Energy Conservation, Waste Management, Sustainable Hotel Designs, and Reforestation. A variety of perspectives was expressed amongst the respondents regarding innovations. Out of the nineteen sampled accommodation units, fourteen units indicated they were engaged in the sustainability of some sort.

6.1. Water conservation initiatives are pursued

The most interesting finding was that out of the fourteen accommodation units, nine indicated that they were engaged in water conservation activities. For instance, Officer F said:

We have a towel talk card where we encourage customers to reuse towels at will just to help us preserve the usage of water. In addition, we are changing ordinary water taps to water-saving gadgets so that we help conserve water.

Focus Group B also revealed that: ‘We have water – talk cards where we advise our long staying guests to decide when their bedroom linen should be changed.’ These results suggest these accommodation units adapted the towel talk innovation to preserve water. The indication here is that the aim of adapting this innovation was cost-saving. Similarly, the revelation that the accommodation replaced ordinary water taps with new water-saving taps suggests that cost saving was a major factor in adopting this new technology. Talking on the same issue of water conservation, Officer G said: ‘We have boreholes that provide us with water in times of water shortage.’ Similarly, Officer J said: ‘I have my water treatment plant in case the water board fails to supply I use my treated water to run my operations.’ Focus Group A also reiterated that: ‘We have a borehole which we use to water the plants other than relying on water from the Water Board.’ Focus Group B again confirmed the practice by saying:

We have a borehole that we use to water our gardens and we also have a stream that runs behind this hotel which we have blocked to divert the water to water our gardens as opposed to using the water from the Water Board.

Officer O also said: ‘We have a borehole that supplies water for the garden and refilling our swimming pool.’ And lastly, Officer T said:

I use borehole water to water my garden. Water from the Water Board is very expensive so I decided to drill my borehole to water my gardens. Also, water from the Lilongwe Water Board is not enough to suffice demand.

These results indicate that a borehole was another preferred innovation. These results may be suggesting two reasons for adopting this innovation. One is the intermittent water supply in Lilongwe and Two, as a cost-cutting initiative. This, therefore, suggests that there is a strong relationship between cost-cutting and adoption of borehole innovations within the accommodation sector in Lilongwe.

Another important finding indicated there was another way of making sure that the water is conserved. Focus Group A revealed: ‘We sensitize staff to ensure that any water leakage has to be reported immediately to the maintenance section. Our car washers use buckets instead of horse pipes to reduce the amount of water used on the same.’ Talking to the same innovation, Officer N said: ‘We train our staff that when they are doing the washing they should use the basin instead of running water and that saves us a lot on water bills.’ Officer P also said: ‘We have started zero gardening principles which guide us in resource usage like water. Our gardeners are watered during the morning and evening hours to minimize water loss through evaporation.’ These results are further indicating that cost saving is the most prevalent factor that drives innovativeness within the accommodation units in Lilongwe.

6.2. Energy conservation initiatives are adopted

Nine accommodation units indicated that they were practising energy conservation. Officer F said: ‘We have automatic switches in hotels like Sunbird Capital and Mount Soche we have these switches that use a card slot.’ Officer K also said: ‘The cost-cutting measures that are in place, for instance, we now have energy saver bulbs in rooms because of these bulbs last longer and they consume less energy.’ Focus Group A mentioned: ‘We have made sure that this hotel uses energy saver bulbs in all areas that require eliminating.’ Focus Group B also mentioned: ‘We use the key card system. The guest inserts this card in its socket to power the room and when the guest leaves the room with this key card, automatically the electricity is cut off.’ Officer N also said: ‘We changed our lighting system four months ago to LED lights 2 or 5 watts. We are saving on each meter a 100 thousand kwacha a month per meter. And our bills are still dropping.’

These results are suggesting that these accommodation units implemented energy-saving technology to reduce their costs.

Another dimension of energy conservation was also revealed by the data. Officer J indicated: ‘I had solar panels on top of the houses and the water pump but they stole the solar panel and now I have gone back to using ESCOM power.’ Officer Q also said: ‘We have solar water heaters; they back up our electric water heaters because of the bigger numbers of people that stay here.’ Officer T indicated: ‘I have decided to start using solar power in my rooms because of the frequent power interruptions.’ These results are indicating that accommodation units in Lilongwe have started adopting new technology that provides an alternative source of energy because the only energy provider in Malawi, ESCOM does not have enough capacity to supply energy. Whilst talking to the same point, respondents revealed another innovation that they adopted to conserve energy. Focus Group A mentioned:

There is an instruction that whenever we are going out of the offices we have to switch off all the lights and the equipment. We have a preventative maintenance system to fix all our faulty equipment to minimize energy wastage.

Focus Group B also mentioned: ‘We also encourage our kitchen staff and laundry staff to switch off the equipment is they are not in use to preserve energy in this hotel.’ Similarly, Officer N said: ‘We switch off our geysers from 9:00 am to 4:00 pm. We do this so that we don’t spend energy on water heating unnecessarily.’ Officer V said: ‘We have notes placed in all our rooms advising our guests on the usage of these air conditioners because we want to conserve power.’

These results suggest that to reduce energy costs, these accommodation units’ innovated ways of engaging their members of staff in the conservation efforts and reduce their operating costs.

6.3. Waste management innovations

Another important finding from this study was that the accommodation units recycle and make compost. Officer G said: ‘We separate plastic bottles from the other waste and this initiative is done by individual employees because they make some money from these empty plastic bottles.’ Commenting on waste management practices Officer N said: ‘We separate our trash here.’ Officer T said: ‘I also bury some waste to make manure.’ Talking to the same issue, Officer O also said: ‘We recycle the plastic bottle and glass bottles. We use spare parts from old cars corrected from scrapyards as decoration. The vegetable waste and other kitchen food waste are turned into compost manure for our gardens.’ Similarly, Officer Q also said: ‘We encourage our staff to recycle materials. We compost a lot of garden waste.’

The possible explanation for these findings is that members of staff within some of these accommodation units found waste as an opportunity to make money especially plastic bottles. The indication here is that this innovation is a temporary arrangement and cannot be accredited as an initiative by the unit. These results also suggest that some accommodation units recycle materials that are sourced from their surrounding vicinity, thus they create a source of income for the local community whilst implicitly removing trash from the environment. Some units use manure in their gardens and reduce the use of chemical fertilisers.

6.4. Sustainable hotel design and reforestation initiatives

Out of the nineteen accommodation units, only two units indicated that they adopted this innovation. Officer J said: ‘You see even this building everything here is made from materials made in Malawi that is what tourists want to see. Everything in my lodge is local and that is what tourists love to see.’ Officer Q also said: ‘Most of our structures are made of wood and are thatched with locally sourced grass materials.’ Talking about reforestation innovative initiatives four accommodation units mentioned that they engage in reforestation activities in Lilongwe. Focus Group B mentioned: ‘We donate seedlings to the City Assembly and we jointly go to Kauma where there is Sewage Plant System to plant trees. This is an annual event so that these trees should help in air purification.’ Officer M said: ‘We go to the Forestry Department, we tell them if you look at the new tree planting season we will give you this number of trees that you can use in planting back.’ Officer O also said: ‘We believe in planting trees, as you can see that this hotel is surrounded by trees. We make sure that we plant trees and that this place is green.’ Officer L said: ‘Over the past three years, we have contributed to the planting of trees in Mbwatalika area to make sure that the green environment is promoted because these trees influence rainfall pattern.’ These results suggest that these units adopted tree planting initiatives to address the needs of their target markets this is in line with Bruns-Smith et al. (Citation2015).

Turning now to evidence from the field visits and pictures from the websites (). These results suggest that some accommodation units practice what the respondents revealed. However, the result in is contradicting what some of the respondents said. The bare ground of Kauma Sewage Plant area could be indicating that the donated trees are not planted there.

Figure 4. Mabuya Camp Lodge built with recyclable materials. Source: https://www.mabuyacamp.com. Accessed 14 August 2018.

Figure 5. Latitude 13 Hotel Reception Area made from Recycled Scrap Motor Vehicle Parts. Source: https://www.tripadvisor.com. Accessed 14 August 2018.

The study set out with the aim of assessing environmental sustainability innovations in the accommodation sub-sector of Lilongwe. The most interesting finding was that the regulating authorities were aware of the bad practices that some hotels in Lilongwe engaged in. However, the results from the hotels and observations made were encouraging because they suggested that efforts are being pursued in some hotels regarding environmental sustainability innovations. This development is in line with Legrand et al. (Citation2013), Kasim et al. (Citation2014), and Fraj et al. (Citation2015). An implication of this is the possibility that the hotels may not be aware that the government has put in place an appropriate legal framework to allow for the propagation of environmental sustainability innovations.

7. Recommendations

The paper recommends that the public sector and the private sector needs to work together to consolidate what has been achieved so far in conservation efforts. This joint effort would enable both parties to formulate guidelines for best practices in environmental management and suggest incentives that would entice the private sector to endeavour innovative ways of sustainable hospitality sector development. In turn, these innovative ways would promote sustainable tourism development in Malawi at large.

8. Conclusion

This study set out with the aim of assessing sustainability innovativeness within the accommodation units in Lilongwe. Furthermore, this study set out to determine the environmental sustainability innovativeness of the accommodation units in Lilongwe. The results suggest that some accommodation units in Lilongwe conserve water and energy, recycle waste, make compost manure as opposed to using chemical fertilisers in their gardens and sustainably design their buildings. The results have shown that the lodging facilities in Lilongwe are dissimilar in the sense that some facilities are making attempts to adopt sustainability innovations whilst others are not. It was also shown that some regulators are not well conversant with the current practices within the lodging facilities. Taken together, these findings suggest that the accommodation units are allowed to practice as it pleases them such that an innovation that is seen to be cost-effective becomes the most appealing to them. The observation made from the results is that there is a strong relationship between resource conservation innovation in lodging facilities in Lilongwe and cost-saving. In this regard, therefore, this study extends our knowledge on the altitude that lodging facilities and regulators have towards sustainability in Lilongwe, Malawi, sub – Sahara African and the rest of the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Lameck Zetu Khonje http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7401-3590

Regis Musavengane http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5276-7911

References

- Alvarez, MD. 2014. Sustainability issues. In E Fayos-solà, MD Alvarez & C Cooper (Eds.), Tourism as an instrument for development: A theoretical and practical study (Bridging tourism theory and practice, volume 5). Emerald Group.

- Aragon-Correa, JA, Martin-Tapia, I & Torre-Ruiz, J, 2015. Sustainability issues and hospitality and tourism firms’ strategies: analytical review and future directions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 27(3), 498–522.

- Bello, FG, Banda, WJ & Kamanga, G, 2017. Corporate social Responsibility (CSR) practices in the hospitality industry in Malawi. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6(3), 1–21.

- Berezan, O, Raab, C, Yoo, M & Love, C, 2013. Sustainable hotel practices and nationality: The impact on guest satisfaction and guest intention to return. International Journal of Hospitality Management 34, 227–33.

- Bernard, HR, 2006. Research Methods in anthropology – qualitative and quantitative approaches. AltaMira Press, Oxford.

- Bisgaard, T, Henriksen, K & Bjerre, M, 2012. Green business model innovation conceptualisation, next practice and policy. Nordic Innovation Publication, Oslo.

- Bohdanowicz, P, Zientara, P & Novotna, E, 2011. International hotel chains and environmental protection: An analysis of Hilton’s We Care! Programme (Europe, 2006–2008). Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(7), 797–816.

- Booyens, I, 2012. Innovation in tourism: A new focus for research and policy development in South Africa. Africa Insight 42(2), 112–26.

- Booyens, I & Rodgerson, CM, 2016. Tourism innovation in the global South: Evidence from the Western Cape, South Africa. International Journal of Tourism Research 18(5), 515–24.

- Borden, DS, Coles, T & Shaw, G, 2017. Social marketing, sustainable tourism, and small/medium size tourism enterprises: Challenges and opportunities for changing guest behaviour. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25(7), 903–20.

- Bruns-Smith, A, Choy, V, Chong, H & Verma, R, 2015. Environmental sustainability in the hospitality industry: Best practices, guest Participation, and customer satisfaction. Cornell Hospitality Report 15(3), 6–16.

- Carasuk, R, Becken, S & Hughey, KF, 2016. Exploring values, drivers, and barriers as antecedents of implementing responsible tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 40(1), 19–36.

- Chan, ES & Hawkins, R, 2010. Attitude towards EMSs in an international hotel: An exploratory case study. International Journal of Hospitality Management 29, 641–651.

- Charmaz, C, 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage, London.

- Charmaz, K. 1996. The search for meanings – Grounded Theory. In JA Smith, R Harré & LV Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking methods in psychology. Sage Publication, London.

- Cilliérs, F, Davis, C & Bezuidenhout, R-M, 2014. Research matters. Juta & Company Ltd, Cape Town.

- Claver-Cortés, E, Molina-Azorín, JF, Pereira-Moliner, J & López-Gamero, M, 2015. The effects of quality and environmental management on competitive advantage: A mixed-methods study in the hotel industry. Tourism Management 50(C), 41–54.

- Corbin, J & Strauss, A, 1990. Grounded Theory research – procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology 15(1), 1–20.

- Cvelbar, LK & Dwyer, L, 2013. An importance–performance analysis of sustainability factors for long-term strategy planning in Slovenian hotels. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(3), 487–504.

- Denzin, NK & Lincoln, SY, 2011. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage, Los Angeles, CA.

- Dibra, M, 2015. Rogers theory on diffusion of innovation – the most appropriate theoretical model in the study of factors influencing the integration of sustainability in tourism businesses. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 195, 1453–62.

- Doherty, L, 2013. Environmental sustainability practices in the hospitality industry of Orange country, California. California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo.

- Foster, JB, 2008. Ecology and the transition from capitalism to socialism. Monthly Review 60(6), 1–12.

- Foster, JB, 2013. Marx and the rift in the universal metabolism of nature. Monthly Review 65(7), 1–19.

- Fraj, E, Matute, J & Melero, I, 2015. Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tourism Management 46, 30–42.

- Glaser, BG, 1992. Emergence vs forcing: Basics of Grounded Theory analysis. The Sociology Press, Mill Valley, CA.

- Glaser, BG, 2016. Grounded Theory description: No no no. The Grounded Theory Review 15, 2.

- Goldstein, KA, Primlani, RV, Rushmore, S & Thadani, M, 2012, February. Current trends and opportunities in hotel sustainability. HVS Sustainability Services, 1(1), 1–9.

- Government of Malawi, 2017. Licenced and graded units. Lilongwe: Department of Tourism.

- Hang, X, Diane, P & Stephen, K, 2016. Peer effects in the diffusion of innovations: Theory and simulation. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 63, 1–13.

- Houdre’, H, 2011. Sustainable hospitality – triple bottom line strategy in the Hotel industry. National Park Service, Washington, DC.

- Hulse, JH, 2007. Sustainable development at risk – ignoring the past. Cambridge University Press, New Delhi.

- Kasim, A, 2007. Business's environmental Responsibility in the hospitality industry. Journal of Management 2(1), 5–23.

- Kasim, A, Gursoy, D, Okumus, F & Wong, A, 2014. The importance of water management in hotels: A framework for sustainability through innovation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22(7), 1090–107.

- Kuščer, K, Mihalič, T & Pechlaner, H, 2017. Innovation, sustainable tourism and environments in mountain destination development: a comparative analysis of Austria, Slovenia and Switzerland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25(4), 489–504.

- Legrand, W, Sloan, P & Chen, JS, 2013. Sustainability in the hospitality industry: Principles of sustainable operations. 2nd edn. Routledge, New York.

- Magombo, A & Rogerson, CM, 2012. The evolution of the tourism sector in Malawi. Africa Insight 42(2), 46–65.

- Magombo, A, Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2017. Accommodation services for competitive tourism in Sub-Saharan Africa: historical evidence from Malawi. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 38, 73–92.

- Merriam, SB, 2009. Qualitative research – a guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons, San Francisco.

- Merwe, M & Wöcke, A, 2007. An investigation into responsible tourism practices in the South African hotel industry. South African Journal of Business Management 38(2), 1–15.

- Middleton, N, 2013. The global Casino: An Introduction to environmental issues. 5th edn. Routledge, London.

- Mohapatra, T, 2016, December 29. How green is your hotel: Sustainability in the hotel industry. Urbanpixels Website: www.greenHome NYC.org. Accessed 18 May 2017.

- Murray, CE, 2009. Diffusion of innovation theory: A bridge for the research-practice gap in counseling. Journal of Counseling and Development 87, 108–116.

- Musavengane, R, 2019. Small hotels and responsible tourism practice: Hoteliers’ perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 220, 786–799.

- Mwale, HF, Chiotha, S & Phalira, W, 2013. Rural livelihoods, environmental sustainability and climate change in Malawi: An annotated bibliography. LEAD, Zomba.

- Nsiku, N & Kiratu, S, 2009. Sustainable development impacts of Investment incentives: A case study of Malawi’s tourism sector. International Institute for Sustainable Development, Manitoba.

- Priego, MJ, Najera, JJ & Font, X, 2011. Environmental management decision-making in certified hotels. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(3), 361–381.

- Radwan, HR, Jones, E & Minoli, D, 2012. Solid waste management in small hotels: a comparison of green and non-green small hotels in Wales. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(4), 533–550.

- Rathore, J, Gawankar, D & Mills, JE, 2009. Exploring sustainability practices in the hotel industry. University of New Haven Undergraduate Research Fellowship 1, 1–5.

- Razumova, M, Ibáñez, JL & Palmer, JR-M, 2015. Drivers of environmental innovation in Majorcan hotels. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 23(10), 1529–49.

- Rodríguez-Antón, JM, Alonso-Almeida, M, Celemín, MS & Rubio, L, 2012. Use of different sustainability management systems in the hospitality industry. The case of Spanish hotels. Journal of Cleaner Production 22(1), 76–84.

- Rogerson, JM & Sims, SR, 2012. The greening of urban hotels in south Africa: Evidence from Gauteng. Urban Forum 23(3), 391–407.

- Smith, C & Leonard, L, 2018. Examining governance and collaboration for enforcement of hotel greening in Gauteng, South Africa: towards a network governance structure. e-Review of Tourism Research (eRTR) 15(6), 480–502.

- Strauss, AL & Corbin, J, 1998. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded Theory procedures and techniques. 2nd edn. Sage, London.

- Wanda, EM, Nyoni, H, Mamba, BB & Msagati, TA, 2017. Occurrence of emerging micropollutants in water systems in Gauteng, Mpumalanga, and North West Provinces, South Africa. Environmental Research and Public Health 14(79), 1–28.

- Warren, C, Becken, S & Coghlan, A, 2017. Using persuasive communication to co-create behavioural change – engaging with guests to save resources at tourist accommodation facilities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25(7), 935–54.

- Willig, C, 2008. Introducing Qualitative research in psychology - adventures in theory and method. Mc Graw Hill, Glasgow.