ABSTRACT

Growing agriculture can reduce poverty, create economic opportunities in rural and peri-urban areas, and boost employment, particularly for semi- and unskilled workers. We review several successful joint ventures across South Africa which comprise a range of partnerships between smallholders, commercial farmers, agribusinesses, industry associations and government. Many of these partnerships have generated significant returns and transformational benefits. Well-designed joint ventures can complement existing government initiatives to drive more rapid agrarian transformation and increase production (Steenkamp, A., Pieterse, D & Rycroft, J, 2017. Innovative joint ventures can boost agriculture production and promote agrarian transformation. http://www.econ3×3.org/sites/default/files/articles/Steenkamp%20et%20al%202017%20Joint%20ventures%20and%20agrarian%20transformation.pdf Accessed 19 February 2019). A review of international best practice provides some insights into how government can support the sector to scale-up these interventions. We argue, however, that these interventions must be supported by policy and regulatory certainty and land policies for secure property rights across a range of tenure options.

1. Introduction

Several features of South Africa’s agriculture sector make it important for the pursuit of inclusive economic growth: its rural linkages, ability to absorb less skilled labour, large multipliers due to extensive links with the rest of the economy, globally competitive labour productivity and importance for export-led growth (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). A growing agricultural sector can help South Africa address its challenges of unemployment and low growth and counter rural poverty.

Despite these advantages, the sector continues to experience low growth and declining employment over the long term. Commercial agriculture has suffered subdued capital investment, low growth, rising debt and policy uncertainty (whilst remaining largely profitable). Smallholder farmers, who are a potential source of job creation, struggle with access to finance, agronomic challenges such as disease management and seed quality, product quality and insufficient support from extension services (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). Given South Africa’s history of distorted land tenure and land ownership, it is critical to grow the sector whilst simultaneously addressing the unequal distribution of income and assets. This includes the important role of asset ownership in securing loans which can unlock wealth and improve productivity in the long run (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017).

All this implies that agrarian transformation is crucial, requiring a fundamental change in the systems and patterns of ownership and control in agriculture and the creation of vibrant, equitable and sustainable rural communities (Cousins, Citation2013 in Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses how successful innovative joint ventures between smallholders, commercial farmers, agribusinesses, industry associations and government can help drive agrarian transformation and address the binding constraints faced by smallholders. Section 3 looks at how government can support the sector to scale-up these interventions and ensure their success by creating an enabling environment for investment based on a review of international best practice. Section 4 discusses the policy requirements to create a conducive environment for investment in agriculture. The final section summarises the main findings and policy suggestions of the paper.

2. Key lessons and principles from a review of selected successful domestic joint ventures

Some are critical of joint ventures as a panacea for agriculture and land reform in South Africa (see Anseeuw et al., Citation2015b). They point to the limited number of success stories, unequal power relations and skewed benefits between partners and communities, a loss of control and decision rights over production and resources, and a (questionable) implicit assumption that the commercial farming model is superior. Mkhabela (Citation2018) indicates that moral hazard and adverse selection can be major limitations to the success of joint ventures. General information asymmetry between the principal (established agribusiness/commercial farmer) and the agent (smallholder farmer/primary producers) can lead to an unequal relationship where one party is at a disadvantage compared to the other which generates mistrust and suspicion between the partners (Mkhabela, Citation2018). For example, disadvantaged and more illiterate primary producers in partnership with established agribusinesses tend to accept lower payment for their produce or lack the ability to enforce terms of the contract, which skews the benefits from joint ventures in favour of the privileged elite who are more powerful due either to their political connectedness or higher than average level of education and literary and economic standing in society (Mkhabela, Citation2018).

Despite these challenges, there is general acknowledgement that joint ventures can yield encouraging results for smallholders. These include increased production, access to services such as training and technical assistance, access to inputs and production credit, as well as access to formal markets (including compliance with standards). There indeed are many examples of commercial farmers, farmers’ organisations and other private-sector institutions that have elected to drive agrarian transformation through partnerships (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). These aim to overcome the challenges faced by the sector. In this section, we draw key lessons from a review of fifteen case studies – initiatives that have contributed significantly towards agrarian transformation. These case studies were selected through a desk-top exercise with some site visits. This was followed by contacting the people involved in the initiatives to verify information and request permission for the information to be included in our review.

Based on this review, we outline a common set of principles and success factors to guide such initiatives, citing some examples.

2.1. The private sector led the design and implementation across the selected projects

The private sector has played a critical role in the success of these projects from their inception (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). Significant buy-in and commitment from private sector players, including commercial farmers, large-scale agri-processors, retailers, large and small-scale cooperatives and industry associations are clearly shown as an important factor of success in each project. In most cases, the various players took it upon themselves to address and expedite agrarian transformation in their respective subsectors and regions. Due to their established position in the market, private-sector partners are able to help beneficiaries overcome their unique financing and working-capital constraints as well as risk-management concerns (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017).

Table 1. Selected initiatives categorised by general theme.

An example is Cedar Citrus, the citrus industry's first farmworker-equity share scheme (project 9 in ). It is jointly owned by the owners of ALG Estates and 23 long-term employees of ALG Estates (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). The employees own 50% of the farm. Cedar Citrus was established, led and funded by the owners of ALG Estates as part of a land redistribution programme on their property. The owners of ALG Estates donated 36 hectares of water-use rights to Cedar Citrus, took out loan finance to establish 36 000 citrus trees – partially funded by the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) – and covered all operating costs until the orchards reached production. These support measures were crucial to the success and profitability of Cedar Citrus, which has paid dividends to beneficiaries since 2010 and is expanding production further.

2.2. Access to finance is essential for the implementation and long term sustainability of agrarian transformation

Most of these initiatives require funds from a combination of private and public sources. These include the commercial farmers, agribusinesses, public finance corporations, development finance institutions and government departments (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). The type of financing varies significantly across projects. Types of support include soft loans, government grants, provision of infrastructure and moveable assets, infrastructure and asset sharing, and direct funds from commercial partners. Each of these constitutes a form of concessional finance.

The Grassland Development Trust (GDT; project 12 in ) is a successful empowerment project benefitting 49 current and past employees of Grasslands Agriculture, a large commercial milk producer (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). GDT purchased the Schoonfontein dairy farm with grant funding from the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development (LRAD) programme of the Department of Land Affairs. The grant covered 35% of the purchase price, while the remaining 65% was funded by a private loan from Standard Bank under its Khula Land Reform Empowerment Facility (LREF). Grasslands Agriculture contributes all working capital including cows, tractors and other implements to the farm. In return it receives half of the revenues from milk sales. The initiative has transferred 100% land ownership to the beneficiaries of the trust and provides substantial financial benefit, mentoring and training to them. GDT (as the landowner and employer) has final authority, resulting in genuine empowerment (Steenkamp et al., Citation2107).

The Suurbraak Grain Farmers Cooperative comprises smallholders farming on communal land in Suurbraak in the Southern Cape (project 11 in ). It applied a dynamic funding model during its first five years of operation (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). Production costs were fully funded by an allocation from the Commodity Project Allocation Committee (CPAC) of the Western Cape Department of Agriculture, which was phased out over four years. Members of the cooperative contribute 10% of their annual gross harvest earnings towards the cooperative’s central reserve fund. This fund assists members to farm sustainably by sharing the cost of machinery, for example. In 2016, the cooperative’s whole crop was funded by the smallholder farmers from reserves built up in this fund and with loans obtained from Sentraal-Suid Co-Operative (SSK) and SAB Miller. The farming business has become commercially successful and has spurred farming activities on other land available to the community, particularly in sheep farming (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017).

2.3. Successful joint ventures usually possess unique institutional arrangements

The complexity of successful agrarian transformation demands project-specific institutional arrangements that are tailored to the commodity and region in which the project is situated (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). A one-size-fits-all approach, in particular to address land reform, should not be adopted, given the complexity of issues at hand.

Mondi (project 8 in ) decided in 2008 not to contest any claims lodged in terms of the Restitution of Land Rights Act, 1994 as amended. Instead it pursues a programme of large-scale settlements to bring claimant communities into their business (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). Since 2008, Mondi has settled and implemented 17 land-claim partnership agreements. The company has transferred payments of over R60 million to claimant communities in the form of rental payments, production incentives and claimant contractor payments.

The Berekisanang Empowerment Farm (project 6 in ) in the Northern Cape was initiated by Afrifresh, a large fruit exporter and owner of Galactic Deals, a table-grape farm. Afrifresh consulted workers on the farm to gauge their interest in a joint project involving water-use rights (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). In 2012, a farmworkers’ trust comprising 24 farmworkers on Galactic Deals was granted 500 hectares of water-use rights by government. Afrifresh then partnered the Galactic Deals farmworkers trust and the IDC to purchase the adjacent Berekisanang farm. The farmworkers trust used its allocated water-use rights to contribute to the equity and purchase of Berekisanang. This unique institutional arrangement shows how the approval of, and ease of access to water-use rights can be used to foster innovative transformation partnerships led by the private sector that empower emerging farmers.

2.4. Capacity building by means of training programmes, mentoring and hands-on technical assistance is a key feature of the projects reviewed

‘Training and Development for Communal and Emerging Wool Farmers’ is a programme of the National Wool Growers’ Association (NWGA; project 14 in ). It has directly supported over 24 480 small-scale wool growers in communal areas in the Eastern Cape since 1997 (Okunlola et al., Citation2016). This programme has been highly successful in increasing the production of wool, income and position in the wool export industry of these farmers, who run their flocks on communal land. The project breaks the stereotype that only private property and freehold titles can provide a secure basis for market-oriented agricultural development (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017).

2.5. Contract farming can be an effective method of expanding small-scale farming

Contract farming typically involves agribusinesses’ providing small-scale farmers with key inputs (financing, seeds, fertiliser, training, etc.) and then purchasing a certain percentage of the farmers’ output (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). Such partnerships support smallholders to achieve higher productivity, scale, access to inputs and markets and can ultimately help them to advance towards commercial status.

Tongaat Hulett (project 5 in ) uses a variety of programmes to partner with local communities in Kwa-Zulu Natal, including contract farming agreements with small-scale sugar farmers (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). This provides these farmers with guaranteed market access through the supply of sugarcane to three of Tongaat’s sugar mills according to a fixed delivery schedule. Tongaat has a team of technical experts and engagement specialists that support the network of contract farmers – a crucial aspect of the initiative. Through partnerships such as this, the aim is to expand sugarcane production, support socio-economic and infrastructure development and transfer skills to participants.

Massmart (project 2 in ) established a R242 million Supplier Development Fund in 2012. This was part of the approval conditions set by the Competition Commission for Wal-Mart’s purchase of a majority stake in Massmart (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). This fund assists developing small-scale farmers and emerging agribusinesses through purchase agreements, extension services, merchandise safety and quality compliance, in-store promotional and merchandising assistance and financial and business training. The fund is a notable example of how competition policy can be used to trigger support for small-scale farmers and emerging food producers via the procurement requirements of large agribusinesses or retailers (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017).

2.6. Access to domestic and export markets is a significant barrier to entry for small-scale farmers as well as less-established emerging farmers

Cooperation with commercial farmers and large agribusinesses (and, in certain cases, with retailers) is crucial in order to provide smallholder and emerging farmers with an effective channel to access domestic downstream markets as a first step, and to subsequently have any chance of entering the export market (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). Being incorporated into existing market linkages and value chains (of their commercial-farmer or agribusiness partner) is decisive in enabling these farmers to expand and diversify production due to the experience, expertise, regulatory compliance and strong brand reputation of larger agribusinesses.

The Lambasi agricultural initiative is a jointly owned farming operation in the Eastern Cape (project 1 in ). The project was established through collaboration between Anglo American’s enterprise development arm, Zimele and the Jobs Fund (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). The funding was used to finance land preparation, input costs, planting, harvesting and training, as well as the technical support. The initiative successfully aggregated 900 hectares of arable land into a single commercial farming entity, representing 490 individual landowners. The smallholder farmers in Lambasi obtain market access through an agreement with Farmwise Grains to buy their produce. This is known as an ‘offtake agreement’ and is one way to provide smallholder farmers with an effective channel to access markets (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017).

The Bosveld Sitrus Group – through its fully owned subsidiary Richmond Kopano Farming – leases and operates the Richmond farm from the Moletele Community who are the land claimants and property owners (project 7 in ). This farm formed part of a land restitution claim in 2004. The Moletele community benefits in several ways: they receive rental income (which increases each year) as well as an amount based on the turnover of the farm; there are employment opportunities on the farm; employees are given training and skills development; and they have the option to purchase up to 50% of Richmond Kopano Farming at any stage of the partnership (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). The model allows for community members (landowners) who have an interest in agriculture to become part of the business process. Crucially, the Moletele Community benefits from access to the scale and market linkages of the larger Bosveld Sitrus Group through Richmond Kopano Farming – the commercial partner. This allows for the negotiation of discounted prices with the suppliers of packing material, chemicals, fertilisers and also shipping lines (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017).

3. Creating an enabling environment for investment in agriculture: lessons from international best practice

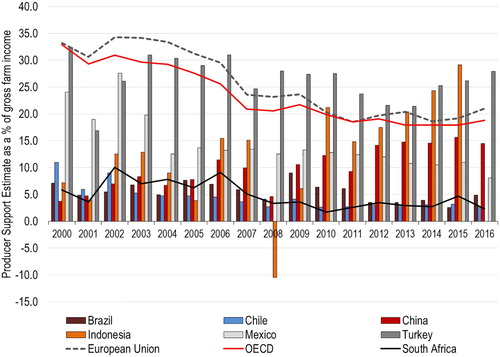

Joint ventures remain an important complement to existing government interventions (such as training and extension services to targeted subsistence and smallholder producers) that are aimed at achieving agrarian transformation while ensuring that agricultural production is not compromised. Such partnerships can be scaled up if government creates a more enabling environment for investment in agriculture through well-designed policies (Steenkamp et al., Citation2017). Most countries with large and growing agricultural sectors provide significant support to commercial and smallholder farmers and maintain a relatively stable, certain and supportive policy environment. South Africa’s agriculture sector receives less government support than those of our global peers and farmers operate in an uncertain policy environment. State support to farmers in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries remains approximately four times higher than in South Africa (see ). Producer support to farmers in peer countries such as Indonesia, China, Turkey and Mexico is also significantly higher than in South Africa.Footnote1

Figure 1. Farmer support estimates by country (as a share of farm income). Source: OECD Producer and Consumer Support Estimates database (OECD, Citation2018).

We argue that South Africa has not taken up all the potential policy space that exists to support the agricultural sector. International best practice provides some insight into how government can support the sector to scale-up agrarian transformation. These recommendations apply to the agriculture sector as a whole, but also emerging farmers, smallholders and land reform beneficiaries, in particular.

3.1. Implement innovative financing solutions required by farmers

Farmers have unique financing requirements. They typically require high levels of debt to offset uneven revenue streams which arise from the seasonal nature of the agricultural production cycle. Farmers require access to credit for operational expenditure and loans are required for capital expansion which exposes them to interest rate movements. This yields farmers particularly sensitive to financing costs, such as interest payments on money borrowed to build or purchase assets (Hong & Hanson, Citation2016). A major requirement for new or expanding farm businesses (especially for high value crops) is long-term loans with delayed interest repayments – this helps farmers to overcome the cash flow difficulties in the early years of establishment and expansion.

An effective means to support agriculture, while limiting the financial burden on the state, is through subsidised interest rate loans. This can involve, for example, a third party paying the interest component on a farmer’s debt or a farmer receiving a loan at a preferential interest rate below market rates. Countries such as Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Turkey, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Russia successfully provide subsidised interest rate loans to farmers (OECD, Citation2017).

In Brazil, the National Rural Credit System (Sistema Nacional do Credito Rural – SNRC) extends concessional agricultural credit to farmers at preferential interest rates for investment, working capital and marketing purposes. Agricultural credit at preferential interest rates is one of Brazil’s main policy instruments to promote productivity and increased income (Lopes & Lowery, Citation2015). Rural credit made available through SNCR is funded from a combination of public and private sources, with about 66 per cent of the total SNCR credit coming from the legal requirement that banks devote part of their deposits to rural credit lines (Lopes & Lowery, Citation2015). Further, below-market interest rates are made possible through a ‘matching’ subsidy, which the Brazilian government pays to financial institutions to incentivise them to extend rural credit that is attractive to producers (i.e. the difference between the interest rates of SNCR credit lines and the market interest rates).

In recent years, the Land Bank has expanded their concessionary finance offering by blending different sources of funding to provide more attractive terms for farmers (Land Bank, Citation2016, Citation2017). To the extent that these products target export-oriented and labour-intensive commodities, it can have significant positive consequences for the rural economy and inclusive growth. Concessionary finance could also increasingly be provided to commercial farmers in exchange for developmental concessions such as equity for farmworkers or contract farming arrangements with smallholders (to ensure they don’t crowd out agribusiness products offered by commercial banks). Concessional finance (including subsidised long-term loans and matching grants) is justified because of the employment-intensive nature of agricultural development, and the need to incentivise investment in the sector.

3.2. Introduce adequate and affordable agriculture insurance

Because the agriculture sector plays an important economic and social role – given its extensive links with the rest of the economy and importance for food security – business continuity in the sector is critical. Agricultural insurance provides farmers with financial coverage against fluctuations in income which may arise from low productivity, caused by catastrophic events such as drought and hail, among others (Iturrioz, Citation2009). Agricultural insurance also enables farmers to obtain credit and financing more easily for investment in inputs, new technologies, tools, and equipment to enhance and expand their production capacity – spurring rural economic development and the modernisation of the agricultural sector.

From an international perspective, it is not uncommon for the state to be a participant in the provision of agricultural insurance programmes (Mahul & Stutley, Citation2010; Loyola et al., Citation2016). This is usually because the business risk of providing agricultural insurance to rural areas, particularly to small-scale farmers, is high resulting in unaffordable premiums for many farmers. Many countries, including Brazil, Canada, Japan, Mexico, India, Spain, Turkey and the US, fully or partially subsidise the provision of insurance for pre-harvest, production and post-harvest risks. In terms of World Trade Organisation (WTO) agreements, direct subsidies by governments are generally not permitted or are required to be gradually reduced, whilst subsidies on agriculture insurance are permitted. This opens the way for governments to assist farmers manage insurable risks and partner with other institutions to offer a viable and accessible insurance product.

In Brazil, the Brazilian Rural Insurance Premium Subsidy Program (PSR) was established in 2003 by the Federal Government. The first PSR operations started through a pilot project in late 2005. The objective of the programme is to enhance protection of farmers from production risks and attract and enable the participation of the private sector in the rural insurance market (Loyola et al., Citation2016). The subsidy reduces the premium paid by the producer, and has led to an expansion of the rural insurance market in Brazil. The state contributes a certain percentage of the insurance premium and the producer pays the remaining part. Without the subsidy, access to agricultural insurance, if sold at market prices, is prohibitive for most farmers. Although expansion has been slow and gradual, in 2013 about 13.8 per cent of Brazil’s agricultural land area had rural insurance coverage (Loyola et al., Citation2016).

Many agricultural producers in South Africa are not insured against the negative impacts resulting from natural disasters, such as drought, mainly due to the high costs associated with agricultural insurance. Two insurance companies have recently withdrawn cover from the agricultural market due to increased frequency and scale of drought and hail. A pilot focussing on a specific value chain and/or geographic location to test a new agricultural insurance product that is based on a partnership between government (through an institution such as the Land Bank), commercial banks and private insurers is an important staring point.

3.3. Improve extension services for smallholder and emerging farmers to support their competitiveness

Extension services have been evolving as an integral part of agricultural development over the past century, and can play a key role in reducing poverty and strengthening rural development (Benson & Jafry, Citation2013).Footnote2 Public extension systems, for the most part, are transitioning towards more decentralised, privatised and demand-driven approaches (Zezza, Citation2002; Mengal et al., Citation2014). Pressure on governments to adopt more decentralised local governance structures and encourage greater participation across stakeholders (including NGOs and cooperatives) and competition from the private sector have also driven the ongoing reform of extension services (Benson & Jafry, Citation2013). A risk to privatised extension provision is that organisations providing such services concentrate only in the locations, crops and farming systems from which profit can be derived, at the expense of not addressing the needs of all farmers (Sulaiman et al., Citation2003). Extension services should be situation-specific, avoid a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach and be subject to comprehensive testing through pilot programmes.

Chile, through the National Institute for Agricultural Development (INDAP), introduced a unique system aimed at facilitating a large-scale roll-out of extension services to its many smallholder farmers (OECD, Citation2008). It uses state subsidies to enable private service providers to deliver extension services to smallholders. State support is necessary as farmers are usually unwilling to pay for the full cost of extension services when delivery is left purely to the market, while the delivery of extension services to small-scale farmers is usually not profitable for the private sector to undertake alone. This leads to a shortage in the supply of extension services, with exceptions where agribusiness firms provide technical assistance to farmers as part of a contract farming schemes. Klerkx et al. (Citation2016) argue that the design of extension services must be flexible enough to deal adequately with differences in terms of production and producers, and facilitate effective dialogue between farmers and suppliers of extension services to match supply with the ever changing needs of farmers.

In South Africa, the quality of extension services is largely inadequate and the coverage ratios are very low. If smallholders and emerging farmers are to transition to higher value horticulture crops, intensive and high-quality extension support is required. The Chilean model, for example, can be adapted in a South African context to involve industry associations and other agribusinesses in the provision of effective extension services to smallholder farmers on a wider scale.

3.4. Improve water use efficiency and expand irrigated agriculture

Access to water and irrigation systems are critical to unlock increased investment in agriculture (National Planning Commission, Citation2012). Agriculture is the largest user of water, consuming over 60 percent of available surface resources (Department of Water and Sanitation, Citation2017). Increasing demand for water, aggravated by climate uncertainty, is in many respects placing agriculture at the ‘back of the queue’ in terms of accessing additional water resources. The challenge for the agricultural sector is to maximise the sector’s potential while achieving transformation and inclusion in the context of constrained water resources. The current 1.5 million hectares under irrigation can be expanded through the better use of existing resources and by developing new water schemes (National Planning Commission, Citation2012). There has also been insufficient investment to reduce the substantial loss of potential crop area and production arising from inefficient irrigation practices and maintenance backlogs. In the Eastern Cape, for example, with more appropriate water management policies it would be possible to increase the acreage under citrus in Sundays River Valley by about 30 percent, with a huge impact on wage-earning opportunities (Sender, Citation2014).

Irrigation is considerably important for reliable agricultural production, and in many countries, the government has played an important role in providing irrigation infrastructure. Chile’s success in exporting agricultural products was the result of public intervention in irrigation and a very effective and transparent water licensing regime for agriculture (Chang, Citation2009).

In South Africa, the Strategic Water Partnership Network (SWPN) is a public-private partnership that is supporting the roll-out of the Water Administration System (WAS) – a water management tool for irrigation schemes to manage their water usage, water distribution and water accounts. One of the main aims of the WAS is to minimise water losses on irrigation schemes that distribute water through canal networks. Phases 1 and 2 of WAS have been implemented, achieving water savings of 191.4 million cubic meters from 2015 to 2017.

3.5. Invest in establishing innovative market linkages for smallholders

Both commercial and smallholder farmers have very different market access requirements. The requirements for smallholders to link to urban markets or modern supply chains are very different to those of commercial farmers of higher-value exports to meet the product standards required to access global markets. Both however are important sources of potential job creation. Contract farming can be an effective method of expanding smallholder farming (Hall et al., Citation2017), and has long been seen as a potential method for growing the agricultural sector in South Africa. However onerous and restrictive contract terms placed on smallholders by large agribusinesses and retailers often hinder any transition to emerging or commercial status. Despite these challenges, there is scope for much more contract farming by large agribusinesses, supermarkets and horticultural exporters.

Various government policies, including the National Development Plan (NDP), identify strategic government procurement as a tool to support smallholder farmers. International best practice on how strategic state procurement has been used to support smallholders can be used to inform the design of a pilot that uses strategic procurement (or structured demand, as it is also known) to support smallholder farmers. Structured demand connects large, predictable sources of demand for agricultural products to smallholder farmers, which reduces risk and encourages improved quality, leading to improved systems, increased income and reduced poverty. A recent successful pilot allowed smallholder farmers in South Africa to supply maize for a World Food Programme initiative in Lesotho (Brand South Africa, Citation2013). To solve the market access constraint faced by smallholders, a strategic procurement mechanism could be put in place to connect smallholder farmers with government contracts in a structured and sustainable way.

4. Policy requirements to create a conducive environment for investment in agriculture

Policy and regulatory certainty is key to reduce risk and attract foreign and domestic investment. The current policy and legislative environment governing the agricultural sector is neither conducive to investment nor works to simplify the regulatory burden on the sector, is complex and diverse and spans multiple departments. Effective policy integration does not only require horizontal coordination among different national departments and agencies, but vertical coordination as well, including the various levels and spheres of government. Effective coordination of efforts and resources is key to improving programme outcomes and investor confidence in the sector. Policy uncertainty and poor implementation of the regulatory framework in certain instances is a major disenabling environment factor for investment. It is especially the issues regarding land and water reform, and the concomitant erosion of individual ownership or property rights that is deterring investment in the sector.

4.1. Uncertainty generated by land reform policies: feedback from commercial and smallholder farmers

While the sector is robust and resilient, policy uncertainty – particularly around land reform, is having a negative impact on investment and weighing on the sector’s growth and job creation potential as outlined in the NDP. Many commercial farmers accept that land reform must and will happen, but there are several aspects of the current programme that prevent farmers from investing in agriculture. First, farmers in areas with frequent and significant land claims are currently not investing because of significant uncertainty about whether the price paid for the farm once the claim is settled will reflect recent investments. This is further compounded by uncertainty around the role of the Office of the Valuer-General in deciding on farm valuations. Second, the land reform landscape is constantly changing (e.g. reopening of land claims plus recent farm ownership proposals), which deters long-term investment. Third, there is uncertainty about land reform processes, funding and contact persons: many commercial farmers want to participate in land reform or agrarian transformation, but do not know what procedure to follow and who to contact.

Uncertainty in land reform also means that South Africa is unable to make the necessary and important structural adjustments in agriculture. Market dynamics and declining yields mean that growing sugar in Kwa-Zulu Natal (KZN) is under severe strain and many sugar mills (that support large rural communities) are closing. Continued policy uncertainty means that farmers in KZN and Mpumalanga cannot switch from traditional low-value and low labour intensive crops (such as sugar cane and forestry) to high value labour intensive export crops such as macadamia nuts (where South Africa is the world’s largest exporter and has some of the highest yields in the world). In addition, many sugar cane and forestry firms (e.g. Illovo, SAPPI and Mondi) are consistently moving their farming activities into Africa as infrastructure improves – where land is cheaper and water is less scarce.

The negative impact of the uncertainty generated by a changing land reform landscape on agricultural development is compounded by: (i) recurrent problems in land reform implementation that remain unaddressed; and (ii) severe capacity constraints faced by the government departments that provide critical support to land reform beneficiaries. First, five recurrent problems have been identified (Anseeuw et al., Citation2015a):

The non-feasibility and non-viability of many land reform projects: too many beneficiaries on projects that are too small, very isolated and devoid of elementary rural and agricultural infrastructure.

Unadapted institutional structures: legal entities that group large numbers of beneficiaries and non-recognised land tenure rights.

A lack of collective action and institutional isolation: many beneficiaries are isolated and lack post-settlement support.

Support measures that are insufficient and not adapted: support measures are structured for a single large-scale commercial farming entity whereas the actual farming taking place is often very different.

Cumbersome, ineffective and non-transparent administration: in certain regions, beneficiaries can wait for more than six years to receive title deeds to their land.

4.2. Certainty and security of rights across a variety of tenure options

Tenure security is vital to secure incomes for existing farmers and to attract new entrants into agriculture. The South African tenure landscape is a product of our unique history. It incorporates traditional, registration-based forms of land rights (outright ownership and certain registered rights, secured through the framework provided by the Deeds Registry Act, 1937, as amended), and extends into communally held property rights, which often have a strong customary law component in respect of distribution. A key challenge is that tenure legislation regarding communal land rights remains non-existent, and in recent times, there has been a seemingly incompatible match between constitutionalism and traditional leadership (see for instance Claassens, Citation2008).

Studies of the land allocation process within traditional areas in the Eastern Cape reveal fault lines between traditional leaders and ward councillors, resulting in vastly different land tenure and usage right allocation systems (Bennett et al., Citation2013). Other factors, like the active role played by traditional leaders as election brokers in rural areas (de Kadt & Larreguy, Citation2015), suggest the strong influence of non-property related factors in the allocation of property rights. Unlike property rights holders in the formal, registered property rights environment; people with informal or communal land rights need to rely heavily on social mechanisms to protect and enforce transactions – resulting in different qualities of institutions and the need for self-enforcement of the same types of rights (Eggertsson, Citation2013).

One response to the question of varying certainties across a range of property rights is to suggest that everybody should be awarded title deeds (de Soto, Citation2000). In this way, every property rights holder is subject to the same system, and therefore the same certainties. However, between the costs of extending a registration system and the unintended negative consequences on the poor, title deeds are arguably not a panacea for providing secure tenure (Kingwill et al., Citation2006).

There may be opportunities to advance tenure security outside of mainstream approaches. If given appropriate policy consideration and implementation resources, these approaches could have significant impact in South Africa. The Philippines, for example, included within their Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Programme an option for landowners and restitution applicants to conclude a voluntary settlement that had a lesser impact on State resources – a move that could allow the development of interesting models and partnerships between existing landowners and claimant communities (Ballestros & dela Cruz, Citation2006). Certainly, in a South African context, landowners and communities frustrated by the slow pace of restitution settlements would welcome an opportunity to engage outside of state facilitation. In Afghanistan, there has been moderate success in the implementation of community-driven land registration mechanisms, where such mechanisms were designed to work alongside existing traditional leadership systems (Murtazashvili & Murtazashvili, Citation2016).

Drawing from these, one way to improve tenure security in South Africa would be to provide a mechanism for communities to develop a register of tenure rights at a local level, driven through District Land Committees, and for the State to focus on providing process certainty to allow rights holders to transact with these property rights. The availability of these mechanisms coupled with the freedom to securely transact (and to realise gains from trade, and thus stimulating investment into property) will assist in unlocking some economic gain, particularly in the rural economy.

5. Concluding remarks

There is a very strong argument for agriculture to play an important role in addressing South Africa’s challenges of unemployment and low growth. Many commercial farmers, farmer organisations and private sector institutions have elected to drive agrarian transformation themselves through establishing joint ventures that aim to actively overcome challenges faced by the sector. We extract a number of key lessons from various successful agrarian transformation projects we review: the private sector has led the design and implementation of such projects; access to finance is essential for the implementation and long term sustainability of agrarian transformation; successful joint ventures possess unique institutional arrangements; capacity building by means of training programmes, mentoring, and hands-on technical assistance is a key feature of these projects; and contract farming can be an effective method of expanding small-scale farming. These lessons provide useful inputs into the replication or design and implementation of new projects aimed at transformation and output growth in the agricultural sector. Our review of international best practice provides some insight into how government can support the sector to scale-up these interventions and ensure their success. These measures include: implement innovative financing solutions required by farmers; introduce adequate and affordable agricultural insurance; improve extension services for smallholder and emerging farmers to support their competitiveness; improve water use efficiency and expand irrigated agriculture; and invest in establishing innovative market linkages for smallholder farmers. However, it is clear that long-term growth in the sector will be undermined unless these interventions are supported by tenure policies that secure rights and assists in reallocating resources, and policy and regulatory certainty to ensure farmers continue to invest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Producer support refers to the OECD’s Producer Support Estimate (PSE) which measures the financial value of support transferred to agricultural producers, arising from policy measures that support agriculture such as market price support and budgetary payments (OECD, Citation2017).

2 The function of agricultural extension services is mainly to disseminate technology, knowledge and advice to farmers (Benson & Jafry, Citation2013).

References

- Anseeuw, W, Liebenberg, F & Kirsten, J, 2015a. Agrarian reform in South Africa: Objectives, evolutions and results at national level. In Cochet, H, Anseeuw, W & Freuin-Gresh, S (Eds.), South Africa’s agrarian question. HSRC Press, Cape Town, 28–51.

- Anseeuw, W, Fréguin-Gresh, S & Davis, N, 2015b. Contract farming and strategic partnerships: A promising exit or smoke and mirrors? In Cochet, H, Anseeuw, W & Freuin-Gresh, S (Eds.), South Africa’s agrarian question. HSRC Press, Cape Town, 296–313.

- Ballesteros, M & dela Cruz, 2006. Land reform and changes in land ownership concentration: Evidence from rice-growing villages in the Philippines. Philippine institute for development studies (PIDS).

- Bennett, J, Ainslie, A & Davis, J, 2013. Contested institutions? Traditional leaders and land access and control in communal areas of Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Land Use Policy 32, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.10.011

- Benson, A & Jafry, T, 2013. The state of agricultural extension: An overview and new Caveats for the Future. Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 19(4), 381–93. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2013.808502

- Brand South Africa, 2013. SA farmers help out Lesotho. https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/investments-immigration/business/economy/development/farmers-220713 Accessed 17 October 2018.

- Chang, H, 2009. Rethinking public policy in agriculture: Lessons from history, distant and recent. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3), 477–515.

- Claassens, A, 2008. Land, power & custom: Controversies generated by South Africa's communal land rights Act. Juta and Company Ltd, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Cochet, H & Anseeuw, W, 2015. Ambiguities, limits and failures of South Africa’s agrarian reform. In Cochet, H, Anseeuw, W & Freuin-Gresh, S (Eds.), South Africa’s agrarian question. HSRC Press, Cape Town, 267–95.

- Cousins, B, 2013. Opinion: Assessing South Africa’s new land redistribution policies. http://www.focusonland.com/resources/opinion-assessing-south-africas-new-land-redistribution-policies/ Accessed 10 February 2017.

- de Kadt, D & Larreguy, H, 2015. Agents of the regime? Traditional leaders and electoral clientelism in South Africa. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Political Science Department. Research Paper No. 2014–24

- Department of Water and Sanitation, 2017. Draft National Water and Sanitation Master Plan (NW&SMP). http://www.dwa.gov.za/National%20Water%20and%20Sanitation%20Master%20Plan/Documents/171114_NWSMP_Interim%20Report%20Draft2.4&Act.pdf Accessed 13 March 2018.

- de Soto, H, 2000. The mystery of capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. Basic books, London, Great Britain.

- Eggertsson, T, 2013. Quick guide to new institutional economics. Journal of Comparative Economics 41(1), 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2013.01.002

- Hall, R, Scoones, I & Tsikata, D, 2017. Plantations, outgrowers and commercial farming in Africa: Agricultural commercialisation and implications for agrarian change. The Journal of Peasant Studies 44(3), 515–37. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1263187

- Hong, D & Hanson, S, 2016. Scaling up agricultural credit in Africa. Frontier Issues Brief submitted to the Brookings Institution’s Ending Rural Hunger Project. https://oneacrefund.org/documents/104/Scaling_Up_Agricultural_Credit_In_Africa_Farm_Finance.pdf Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Iturrioz, R, 2009. Agricultural insurance. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/FINANCIALSECTOR/Resources/Primer12_Agricultural_Insurance.pdf Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Kingwill, R.., Cousins, B., Cousins, T., Hornby, D., Royston, L & Smit, W, 2006. Mysteries and myths: De Soto, property and poverty in South Africa. Gatekeeper Series – International Institute for Environment and Development Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Programme, 124.

- Klerkx, L, Landini, F & Santoyo-Cortes, H, 2016. Agricultural extension in Latin America: Current dynamics of pluralistic advisory systems in heterogeneous contexts. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 22(5), 389–97. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2016.1227044

- Land Bank, 2016. Annual Integrated Report 2016. http://www.daff.gov.za/daffweb3/Portals/0/SOE/Annual%20report%202016%20land%20bank.pdf Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Land Bank, 2017. Annual Integrated Report 2017. http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/ab09f3_c4ab5e61816640af97dc3a4b39cf4519.pdf Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Lopes, D & Lowery, S, 2015. Rural credit in Brazil: Challenges and opportunities for promoting sustainable agriculture. A Forest Trends Policy Brief. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/ft-mapping-rural-credit-in-brazil_v19_final-rev-pdf.pdf Accessed 22 May 2018.

- Loyola, P., Moreira, VR & da Veiga, CP, 2016. Analysis of the Brazilian program of subsidies for rural insurance premium: Evolution from 2005 to 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301796617_Analysis_of_the_Brazilian_Program_of_Subsidies_for_Rural_Insurance_Premium_Evolution_from_2005_to_2014 Accessed 16 May 2018.

- Mahul, O & Stutley, CJ, 2010. Government support to agricultural insurance: Challenges and options for developing countries. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/ac42ef80426a2aefbb9dbf0dc33b630b/Government±Support±to±Agricultural±Insurance_Mahul±and±Stutley_2010.pdf?MOD=AJPERES Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Mengal, AA, Mirani, Z & Magsi, H, 2014. Historical overview of agricultural extension services in Pakistan. The Macrotheme Review: A Multidisciplinary Journal of Global Macro Trends 3(8), 23–36.

- Mkhabela, T, 2018. Dual moral hazard and adverse selection in South African agribusiness: It takes two to tango. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 21(3), 391–406. doi: 10.22434/IFAMR2016.0177x

- Murtazashvili, I & Murtazashvili, J, 2016. The origins of private property rights: states or customary organizations? Journal of Institutional Economics 12(1), 105–28. doi: 10.1017/S1744137415000065

- National Planning Commission, 2012. National development plan: Our future – make it work. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/NDP-2030-Our-future-make-it-work_r.pdf Accessed 06 March 2018.

- OECD, 2008. Small holder adjustment in Chile and the role of INDAP. https://www.oecd.org/tad/agricultural-policies/41687424.pdf Accessed 22 May 2018.

- OECD, 2017. Agricultural policy monitoring and evaluation 2017. OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr_pol-2017-en Accessed 22 May 2018.

- OECD, 2018. Producer and consumer support estimates database. http://www.oecd.org/tad/agricultural-policies/producerandconsumersupportestimatesdatabase.htm Accessed 22 May 2018.

- Okunlola, A., Ngubane, M., Cousins, B & Du Toit, A, 2016. Challenging the stereotypes: Small-scale black farmers and private sector support programmes in South Africa: A national scan. Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research, Research Report 53: June 2016.

- Sender, J, 2014. Backward capitalism in Rural South Africa: Prospects for accelerating accumulation in the Eastern Cape. http://www.ecsecc.org/documentrepository/informationcentre/ecseccwp17_11974.pdf Accessed 22 May 2018.

- Steenkamp, A., Pieterse, D & Rycroft, J, 2017. Innovative joint ventures can boost agriculture production and promote agrarian transformation. http://www.econ3×3.org/sites/default/files/articles/Steenkamp%20et%20al%202017%20Joint%20ventures%20and%20agrarian%20transformation.pdf Accessed 19 February 2019.

- Sulaiman, RV & Van den Ban, AW, 2003. Funding and delivering agricultural extension in India. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education 10(1), 21–30. doi: 10.5191/jiaee.2003.10103

- Zezza, A, 2002. The changing public role in services to agriculture: The case of information. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/24902/1/cp02ze79.pdf Accessed 22 May 2018.