ABSTRACT

The Namibian government promotes community-based tourism (CBT) as market-based development. At Treesleeper Eco-camp, a CBT-project among marginalised Hai//om and !Xun Bushmen (San), we investigate how Bushmen's historically developed paternalist relations shape contemporary local institutional processes. Institutional design principles, seen as prerequisites for stable and robust institutions (norms, rules and regulations), and thus successful CBT, are used to analyse local changes of the project in relation to a government grant. Ironically, after the grant, Treesleeper generated less income and the consequent ‘upgrade’ intensified conflicts. This study shows that community control, ownership and participation are key factors for successful CBT-projects, but currently the state has obstructed these, just as various other ‘superior’ actors have also done (throughout history) in relation to ‘inferior’ Bushmen. We argue that paternalist ideologies perpetuate today in the Bushmen's relation with the state, leading to weaker institutions locally through dispossession of their sovereignty.

1. Introduction

Namibia, famous for its wildlife, natural sceneries and diverse cultures, has become a popular tourist destination. Since independence in 1990, tourism has become a priority sector for the government and a multitude of community-based tourism (CBT) projects were launched (Novelli & Gebhardt, Citation2007). Such development projects have been both praised and critiqued. Some claim CBT projects promote empowerment, support local people and the economy (Lapeyre, Citation2010), while others maintain that many of these projects fail due to a lack of community participation and local elitism (Blackstock, Citation2005). Moreover, implementing market mechanisms is regarded as the only possible option to further development (Duffy, Citation2006). This aligns with dominant contemporary development thinking, in which ‘the market’ is seen as a natural force to which human life must submit (Ferguson, Citation2006).

In this paper, we analyse the community-based Treesleeper Eco-camp at the Tsintsabis resettlement farm, Namibia (hereafter referred to as Treesleeper), which is run by the local Hai//om and !Xun ‘Bushmen’ (or ‘San’)Footnote1 groups. In the Namibian land reform programme, which has run since independence in 1990, many Bushmen are directed to group resettlement farms that are allocated to a group of people who are expected to use it communally. However, most of these projects have failed many of the national production objectives (Gargallo, Citation2010) and, for Bushmen, resettlement is often an impoverishing experience, also in Tsintsabis (Castelijns, Citation2019). At Tsintsabis, Treesleeper started in 2004, aiming to show the rich culture of the Hai//om and !Xun by creating a campsite and activities for tourists and thereby providing income. To this aim, a representative legal body was set up: the Tsintsabis Trust (TT), which is entitled to make large decisions about Treesleeper and to represent the larger community of Tsintsabis. In the early years, however, two NGOs were represented in the TT (the Dutch Foundation for Sustainable Tourism Namibia, FSTN, and the Legal Assistance Centre, LAC), as well as one ministry (Ministry of Lands and Resettlement, MLR).

1.1. Institutional design principles and participation

For the community-based element of Treesleeper we focus on the way institutions emerged and changed in this participatory development project. Using institutions can lead to a better understanding of local-level processes and its outcomes (Agrawal & Gibson, Citation1999); they are the ‘norms, rules and regulations that shape human expectations and human actions’ (Haller & Galvin, Citation2008) and are interlinked with issues of knowledge, power and control. They can be formal – based on rules and laws which are enforced by third parties – and informal – based on socially shared rules which are created and enforced between the involved actors. Both formal and informal institutions guide interactions, allocate roles and influence rights and access to resources. The way institutions are designed impacts management and governance (Crawford & Ostrom, Citation1995; Ingram, Citation2014). Ostrom’s (Citation1990) eight institutional design principles are seen as prerequisites for stable and robust institutions (Becker & Ostrom, Citation1995). Over time, these principles have been amended, added to and elaborated on, for example by Agrawal & Chhatre (Citation2006), Cox et al. (Citation2010) and Ingram (Citation2014).

Clear institutional frameworks are particularly important for CBT projects in Africa, as these carry well-known risks of appropriation of economic, social or environmental benefits aimed at the host community. Furthermore, if institutional arrangements to govern community-based initiatives are not functioning, this can be counterproductive to sustainable development (Berkes, Citation2004). However, external powers have always had a big impact on local institutional development (Ensminger, Citation1992) and the institutional design principle approach does not address all structural, political economic, ideological and historical explanations, some of which have been added to our analysis here to further address the important issue of power (Haller & Galvin, Citation2008). We therefore position the institutional changes at Treesleeper in the historically developed ideology of paternalism to address the important power relations in development and tourism, specifically with the state. Such an ideology ‘blurs and makes invisible both the violence and the structural conditions that keep some people in power and others disempowered’ (West, Citation2016:5).

1.2. Historical paternalism

Paternalist relationships were widespread over Africa in various forms, as social relations between unequal partners that are interdependent on each other (Van Beek, Citation2011). In this ideology, a crucial aspect is that the ‘governor’, the person in authority, knows best how to govern his ‘subjects’, which happens through edification, care, protection and so on. Governors present themselves as the ones who know what is best in the long run for those they govern, who are seen as immature and incapable of doing this themselves (Gibbon, Daviron & Barral, Citation2014). The different Bushmen groups in southern Africa have gone through a variety of paternalist relationships throughout history, with various other groups acting as ‘superior’ to them and thus regarding them as ‘inferior’. First, many have been engaged as slaves or serfs in a variety of patron-client relationships with black pastoralists already in precolonial social relations (see, for example, Wilmsen, Citation1989; Gordon & Douglas, Citation2000; Dieckmann, Citation2007; Koot & Hitchcock, Citation2019). Second, under colonialism, many of them became farmworkers and ended up in particular southern African relations of baasskap (Sylvain, Citation2001; Koot, Citation2016a). Ideas about white supremacy prevailed in these days and paternalism took shape at the farms where the Bushmen became the ‘children’ of the white, male ‘fathers’; the boss (baas) was the ultimate maker of decisions, concentrating power mostly in the person of the farmer who was in charge of all resources (Du Toit, Citation1993). Third, they have been, and often still are, subjects in relation to development workers (Garland Citation1999; Koot Citation2016b) and fourth, as this paper shows, contemporary government institutes also tend to act as superior governors. This should be seen in a broader societal context, in which the ‘new’ rapidly growing black political and economic elites (Dieckmann, Citation2011) have taken over particular features of superiority that the white colonial settlers also explicitly articulated and today these seem mixed. A black farmer from the area of Tsintsabis, for example, explained that ‘Bushmen […] are the most ignored in Namibia […] they are my kids. […] I bring them up’ (interview 15 May 1999). And in 2006, a black farmer came to visit Treesleeper and asked if the first author (who in 2006 was involved in Treesleeper as a development fieldworker), could send some guys over to his farm so that they could also build such a campsite for him, assuming automatically that he (a white man) decided these things for them. This shows how paternalism is a phenomenon in the Bushmen's social environment that is not anymore restricted to the (white) farms only.

1.3. Institutions, community control and paternalism at Treesleeper Eco-Camp

We show how paternalist ideologies perpetuate today in the Hai//om and !Xun's relation with the Namibian state, leading to weaker institutions locally through the dispossession of sovereignty, which contains

the ability to self-govern (in the state-related political sense as well as in the sense of rights to make decisions about self, land, family and future), as freedom from domination and control, and as the ability to assert autonomy through daily practice and action. (West, Citation2016:35).

In what follows, we first explain our methodology and we elaborate on the Treesleeper case study. Next, we provide our results, with an analysis based on the institutional design principles. In the discussion that follows, we link these findings with a structural, historical analysis of paternalism and how this has informed the changes at Treesleeper. Last, in our conclusion, we argue that institutional changes need to be seen within a larger structural context and that in the case of Treesleeper, Bushmen-state paternalist relations cannot be excluded from the analysis of changes at the local level.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Methods

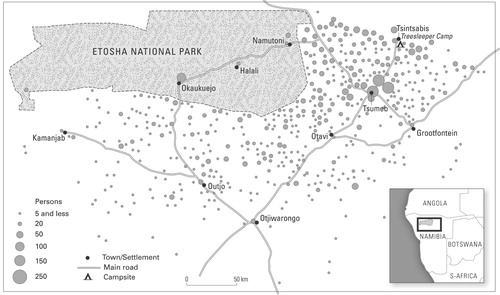

Ethnographic fieldwork was conducted from March until May in 2016 by the third author: participating in the daily lives of people listening, observing, asking and collecting information during interviews. The first author has been doing research in Tsintsabis between 1999 and 2019, living in Tsintsabis and working at Treesleeper between 2002 and 2007 and has maintained the connection with various other Bushmen groups in southern Africa ever since. In this paper, we focus predominantly on the findings from 2016 to explain institutional changes and use the longer running research as contextual data. Respondents from diverse backgrounds were identified in Tsintsabis and selected at random after the third author met them during introductory meetings. After several weeks at the farm specific people were further identified based on their position in the village for their relation to Treesleeper. In total 45 respondents were interviewed using semi-structured interviews (in English, Afrikaans or a local language with translation). Most interviews (29) were done in the respondents’ home or at the Treesleeper office in Tsintsabis (see Map 1), four were conducted in Windhoek (Namibia's capital), three in Tsumeb (a town about 60 kilometres to the South), three in /Gomkhaos (a separate settlement at the Tsintsabis farm) and one in the Netherlands (with a representative of the foundation Connected to Namibia, a Dutch NGO that has in the past played a small role in Treesleeper's starting phase).

The majority of the respondents were of Hai//om ethnicity (15), !Xun (6), mixed background (10), other Namibian ethnic groups (7) or European (7). Importantly, in several of the interviews with Hai//om and !Xun these became group interviews in which many family members or neighbours would join in. The respondents included two employees, nine former employees and four former builders/sub-contractors, an initiator of Treesleeper Eco-camp (who is also an author of this paper), the NGO ‘Connected to Namibia’, the school principal, the former headman of Tsintsabis, a Bushmen expert and his wife (who own a neighbouring farm) and five current and former trustees of the Tsinstabis Trust (TT). Six respondents were interviewed who were formerly involved in Treesleeper tourism activities: the head of a traditional performance family, a former traditional dancer and a person whose house was visited during the village tour, and three MET (Ministry of Environment and Tourism) officials (deputy director of tourism development, senior tourism officer and chief tourism officer of CBT-projects). Financial data are given in Namibian dollars (N$), with the exchange rate as of March 2010 being €1.00 to N$ 9.92 (Currency XE, Citation2019).Footnote2

2.2. Tsintsabis and Treesleeper Eco-camp

Tsintsabis became a resettlement farm in 1993 (Koot, Citation2012). This expensive and slow process (cf. Harring & Odendaal, Citation2002) led to an increased dependency on the government, mistrust of government officials and a lack of participation by the resettled people (Suzman, Citation2001). The LAC (Citation2006:18) claims that ‘Tsintsabis represents a failed model of rural settlement that is all too common in Namibia’; there was a lack in skills and (government) support for the people in Tsintsabis to earn a living, and the location is too far from any economic activity. However, Tsintsabis grew rapidly over the years to approximately 4 000 inhabitants, in an area of 3 000ha (Dieckmann et al., Citation2014). Moreover, in-migrants into Tsintsabis from other ethnic groups are currently becoming ever more dominant in local politics, leading some Hai//om to explain that they ‘feel like they are slaves to the in-migrants’ (Castelijns, Citation2019:25). These in-migrants also occupy much land, apparently because the previous headman sold parts illegally and because they have good connections with the government, so that today ‘all the lands […] has [sic] been sold. To the police officers, to the nurses, people who work in the government, officials’ (interview 30 November 2016, with an elderly woman, quoted in Castelijns, Citation2019:27).

Besides some small scale agriculture, some hunting and gathering and a few small shops and shebeens (unlicensed bars), there are little economic activities and life is hard. Therefore, since 1993 the development committee of Tsintsabis had an idea to start tourism to increase employment (Koot, Citation2012). Based on suggestions of community members, the FSTN supported them to create a community-based campsite and to found the TT in 2004, which became entitled to represent the community of Tsintsabis regarding Treesleeper (Master of the High Court, Citation2004; Hüncke & Koot, Citation2012; Koot, Citation2016b). The basic infrastructure of Treesleeper was built between 2004 and 2007 and tourist activities consisted of a bushwalk, a village tour and a traditional performance. It was always the intention that Treesleeper would be run by the Hai//om and !Xun community of Tsintsabis and thus that FSTN members would at a certain point leave (Hüncke & Koot, Citation2012). The role of the TT is to oversee, monitor and evaluate the activities of Treesleeper (//Khumûb, Citation2008); they are responsible for employment, payments, making decisions, solving problems and keeping in contact with the government. The daily management of the project is executed by a camp manager.

3. Results

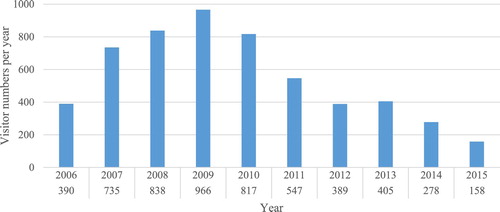

Visitor numbers increased from 390 visitors in 2006 to 966 in 2009, resulting in up to nine jobs and incomes for local craft persons, craft sellers and traditional performers (Hüncke & Koot, Citation2012). The TT used some of the profits as a donation to the kindergarten of Tsintsabis. Troost (Citation2007) found that Treesleeper had led to economic (growing economic activity), social (support of the community), psychological (confidence in the project and pride) and political (some influence in decision-making processes) empowerment in the community and the project was used as a positive example by the Namibian Community-based Tourism Association (NACOBTA) and the Ministry of Lands and Resettlement (MLR) to show other communities how a CBT-project could be run (Koot, Citation2012). In 2009, a N$ 1,2 million grant from the MET aimed to upgrade the camp to a lodge, with construction starting in 2011 but ending in 2013, despite none of the buildings being completed. This MET grant came from EU funds and one condition was that they would start building in June 2010, because it was targeted at upgrading community campsites in southern Africa before the 2010 World Cup Soccer in South Africa. However, because deadlines were not met, tourists visiting Treesleeper began to complain that the camp looked like a construction site, with half-finished buildings and construction waste. Therefore, also tour operators – the most important source of income – started cancelling their visits (//Khumûb, Citation2015) and tourist numbers declined gradually to 158 in 2015 (see ). Of the nine employees, only two remained at work in 2016. The grant can be seen as crucial to the institutional and political changes occurring at and around Treesleeper.

The MET-grant, which was acquired because of the TT's and in particular the camp manager's efforts, was at first sight reason to celebrate the community's use of agency. Ironically, however, it did not have the intended positive effect. The idea was that electricians, brick layers, plumbers and so on from Tsintsabis would be employed during the construction. Moreover, the TT was under the impression that the grant would be paid into their account, but it turned out that MET controlled the process and finances, despite the government's own policies which aim to support small and medium enterprises (Shifidi, Citation2010). Although MET awarded the grant, the mandate for the construction lay with the Ministry of Works and Transport (MWT). The MWT appointed and selected the technical expertise and Treesleeper became the ‘user client’ and MET the client, which meant that the construction team dealt with MET directly. As the architect (who was also the project manager) explained, ‘we hardly actually worked with the user client. All our instructions came from the client’ (interview 26 April 2016).

According to the construction experts, due to many inconsistencies several works had to be redone. Money was an issue, with some claiming the budget was underestimated and uncorrected for inflation. But payments were made in advance, and MET kept paying the contractor, who was considered incompetent by many. In the end, none of the buildings were finished, even at the end of 2017 (Verschuur, personal communication, 9 April 2018). According to MET, an assessment now had to be done by MWT to find out what went wrong, and how to proceed. In terms of ownership, the buildings are government property until they are handed over to Treesleeper, so an MET official explained that ‘they will just have to follow our channels, we [government] will have to guide the process’ (interview 21 April 2016). The government thus states that they will stay in control, clearly positioning themselves as the responsible, superior, party. In fact, at the end of 2017 the Tsintsabis Trust wanted to get written permission from MET to continue construction of the unfinished buildings if funds were raised without government aid, but they never received this and MET continued to wait for MWT's assessment (Verschuur, personal communication, 9 April 2018).

Treesleeper now is divided into a campsite and an unfinished lodge, in which the latter hinders the campsite tourism. The TT has no control over finalizing the upgrade and is dependent upon MET and MWT, and although many community members wanted to know about Treesleeper in the initial years, interest in the project decreased since the upgrade, as Treesleeper was not able to bring benefits back into the community anymore. In 2016, most villagers didn't know what was going on at Treesleeper, as a !Xun man explained ‘the beginning […] I saw the guests coming in. […] But I don't know, after them what has become of it’ (interview 6 May 2016). The benefits that Treesleeper once brought, could no longer be generated, as explained by the TT chairman, ‘when it was Treesleeper campsite tourists came, nothing now’ (interview 16 April 2016).

Some community members think Treesleeper was responsible for hiring constructers from outside Tsintsabis. In response, the TT stopped community meetings as tensions worsened. The camp manager and the former headman were not on good terms, and the downfall of Treesleeper intensified these conflicts, continuing until today (Itamalo, Citation2017; cf. Castelijns, Citation2019). In 2013 a new headmen for Tsintsabis was appointed and the former headman explained that he was forced to step down because he had too many questions about the financial situation of Treesleeper. After his removal he and his followers turned against Treesleeper and the TT, further dividing the community. Many of these allegations concerned finances, in which the camp manager and the TT were accused of stealing, as explained by a former builder that ‘if there was money, then those things [buildings] would be finished, but it was eaten’ (interview 10 May 2016). To counter some allegations, the camp manager was removed from access to the TT bank account.

3.1. Institutional design principles around Treesleeper

Based on the data collected, this section interprets the institutional processes, in terms of the design principles and how they changed at Treesleeper before and after the upgrade. We only analyse the three design principles that have been heavily affected by the grant and the upgrade.Footnote3

3.1.1. Congruence between rules and local needs and conditions

This institutional design principle concerns whether the rules match the local needs and conditions. Rules should conform to local conditions and the need for congruence is necessary between rules and the resource condition. Culture and customs play an important role, with externally imposed rules matching local customs. This principle is often described as the congruence between costs experienced by the users, and the benefits they receive from participating in a project (Cox et al., Citation2010). At Treesleeper, conformation to local conditions is embodied in the Deed of Trust (Master of the High Court, Citation2004), established by the LAC in collaboration with the FSTN and some community members. Some local trustees and community members had difficulties with understanding and implementing these rules and the Deed of Trust in general (Troost, Citation2007). Thus, congruence between the rules of the Deed of Trust and local conditions appeared weak at first. To solve this, the Deed of Trust was explained several times, and amendments/revisions took place after both FSTN members had left in 2007. However, today benefits do not exceed the costs of investments; before the MET grant, the benefits were higher than the costs but today Treesleeper is unable to produce benefits for the wider community. A perceived cost is that the worsening situation of Treesleeper accelerated the division of the community.

3.1.2. Collective choice arrangements and participation of actors

This principle concerns the people affected by rules, who have a say in these rules and their modification (‘collective choice arrangements’). Local knowledge is important, as local people have first-hand information about their situation, and therefore have an advantage in designing new rules and strategies, especially when situations change (Berkes, Citation2004). This design principle strongly aligns with the principle that concerns community and citizen participation, which is particularly important in the formation and consolidation of local democracy (Ribot et al., Citation2008). Participation refers to the influence of the community in decision making that affects their livelihoods. Although community participation is a key element of CBT, the tourism industry in general often resists such community-participation in the decision-making process (Blackstock, Citation2005; Koot, Citation2016a). Individuals affected by Treesleeper should have the possibility of modifying rules and participating in its governance. Within Treesleeper the structure of decision-making is clear and before the upgrade community members also had a say via community meetings, but afterwards few community meetings occurred, which limits information flows to community members and undermines their possibility to participate. Most people thus do not know what is going on at Treesleeper. Furthermore, it is questionable how representative the TT now is for the community, as the trustees have not been chosen by the community, but through other trustees.

3.1.3. Rights to organise

The right of local users to create their own institutions, without external, or government agencies challenging these is a key governance principle. One of the most important aims in CBT-projects is that members of local communities have a high degree of control over the project (Saarinen, Citation2010). This is something that changed seriously due to the upgrade. Although the TT is still entitled to take big decisions about Treesleeper locally, once the grant was given, the TT did not receive the right to manage the upgrade and the grant was controlled by the MWT and the MET. This resembles how, at the start of the project, the FSTN was in control of the money, although an important difference is that the first donations went into a TT account and the FSTN representatives left the project after they handed over control and responsibility of Treesleeper. For the upgrade, MWT appointed a team of experts and a contractor, hereby again ignoring Treesleeper. These accumulated processes have led to the TT increasingly losing control over the upgrade while not being allowed to finish it. So ironically, although the government sees Treesleeper as a community-based project owned by the TT, the rights of the TT to organise and to govern their institutions are now challenged by this same government. This is not something that only happened at Treesleeper. As a former TT member explained about another project in Tsintsabis, a craft centre, the situation is similar, since also here ‘the government is the one controlling […] you don't have a say’ (interview, 29 March 2016).

4. Discussion: institutions and state paternalism

As a development project, Treesleeper is a typical example of ‘anti-politics’ (Ferguson, Citation1990), in which governmentality has functioned to ‘de-politicize’ structural questions of resource distribution and power; bureaucratic state power is guaranteed, even strengthened, based on a discourse of development, while the local population has to deal with the consequences of this development (Ferguson, Citation2006). Already when starting Treesleeper the community-based development discourse, supported by the FSTN, was essentially aimed at supporting the community to engage in capitalist practices through tourism. Such continuing market-based approaches tend to disguise power dynamics and focus on economic benefits mainly as if this is equivalent to empowerment and development (Wilshusen, Citation2014), which they are clearly not. And at a global level, NGOs and the Namibian government have been in a position to use the discourse of community-based development to attract donor funding.

One of the proposed original aims of Treesleeper was a bottom-up approach, but it has changed from an NGO-run to a state-dependent top-down intervention. This strongly contradicts Namibia's policy to expand community involvement in tourism projects (Novelli & Gebhardt, Citation2007). Having become dependent upon state bureaucracy (and in its early stages NGO input), many development programmes are these days planned without the participation of the Bushmen themselves, providing for new forms of domination from external parties. In southern Africa, governments have focused on development strategies that focus on welfare and infrastructure, leaving out important elements such as empowerment, education, political structures, access to natural resources and securing land tenure (Hohmann, Citation2003). This aligns with the idea of a post-apartheid paternalistic government as found in other places in Namibia too where marginalised communities seem to become ever more dependent on government support (Friedman, Citation2011). It then seems as if any development project, so including the idea to start Treesleeper, was welcomed as another way to survive their dire circumstances at the resettlement farm. The external powers are crucial to investigate changes in institutional design principles further. Although these principles are supported in literature, there are also critiques; importantly the design principles are incomplete, and only partly explain the success of an institution (Cox et al., Citation2010), while not fully addressing power relations (Ensminger, Citation1992; Haller & Galvin, Citation2008; Wilshusen, Citation2014).

As Haller & Galvin (Citation2008) showed, history, ideology and political economy are crucial to institutional changes at the local level. The tight control that the Namibian state executed over the grant shows similarities with historical paternalism, an ideology that the Bushmen of southern Africa have experienced for centuries with different ‘governors’ (black pastoralists, white settler farmers, development workers and today, the Namibian state) as their superiors. It is important to acknowledge that paternalism among Bushmen still thrives today in the tourism industry and in the development sector (see Garland, Citation1999; Koot, Citation2015, Citation2016a, Citation2016b), and that the government of Namibia is strongly entangled with both the tourism and the development industry, in particular the MET. Moreover, today most people working at the Namibian ministries are derived from non-Bushmen groups that historically also viewed Bushmen as inferior. It is then hardly surprising that the Bushmen are considered inferior and incapable in their contemporary relations with the state. Many Bushmen groups consider their current governments very similar to the colonial authorities, as externally imposed authorities executing power over them (Barnard, Citation2002). This is shown, for example, in the use of language by government officials who tend to talk about ‘our’ Bushmen people, something they are very unlikely to do with other ethnic groups (Dieckmann, Citation2011). However, state paternalism provides for a different type of paternalism than, for example, colonial settlers, in which the farmer was highly dependent on his labourers; the government is not directly dependent on the Bushmen, but the marginalised status of the Bushmen is something that government actors can use to attract donor funds. As Hohmann (Citation2003) explained, pre-colonial states were superseded by colonial rulers, but features of the pre-colonial political states have survived up until post-colonial days. Through indirect rule, structures of power and dominance have survived throughout colonialism, especially in relation to the Bushmen. Such relations are hardly taken into account in development policies today, and the consequent contemporary state paternalism can easily be obscured by community and (market-based) development rhetoric.

In his seminal work Black Skin, White Masks (Citation1952), Frantz Fanon showed the importance of colonial power relations, and how these evolved into the postcolonial era. Colonial subjects often develop an inferiority complex and try to imitate the dominant culture of the coloniser. In this case, however, the question is whom we should see as the colonial subject; does that mean the Hai//om and !Xun of Tsintsabis, who now seriously wish to engage in capitalist development, just as their former colonisers? Or is the new, mostly black, government of Namibia a former colonial subject who is now imitating paternalist features in their relation with the Bushmen while also striving to implement larger capitalist development ideas? We believe both are the case, since the Hai//om and !Xun have, at the start of Treesleeper, happily engaged in this tourism project, either simply as a survival strategy or as people who also embrace modernity and wish for new livelihood strategies; despite all Treesleeper's problems, they have shown much enthusiasm and agency to benefit from this development initiative and would still love to continue with the project, notwithstanding the current deadlock. This raises an important question, namely whether the current situation for the Bushmen is essentially a different one than their situation before independence? Or, in the words of Fanon (Citation1952; cf. Ferguson, Citation2006), have the new governors, who now are educated and wealthy, not become blacks with white masks?

Despite its importance in development, paternalism is an important ideology that tends to be neglected by stakeholders such as donors, NGOs, private sector partners and governments. It does not only take place at the local level, highly affecting institutional changes, but also at a more structural level. In fact, if governance is ‘a function of power relations by which a certain constellation of participatory institutions is crafted’, the Treesleeper case has shown the importance of ‘power issues and issues of ideology in order to legitimise actions’ (Haller & Galvin Citation2008:22). In tourist developments, nation-states have an essential role since they often have the power to plan and control such developments. Loans, overseas aid and tourism-related international investors are largely channelled through governments, who are also the stakeholders responsible for creating a favourable national policy to assist tourism development. Governments in developing countries are frequently influenced and put under pressure by larger international institutions (Mowforth & Munt, Citation2003), as happened at Treesleeper, where the EU-originated grant was initially pushed to be spent quickly due to the 2010 World Cup Soccer in South Africa. Importantly, paternalist relations do not mean that the Hai//om and !Xun do not have (or never had) any agency; although unequal, these relations are structured from ‘above’ as well as ‘below’.

5. Conclusion

This study shows that at Treesleeper, community control, ownership and participation are key factors for successful CBT-projects, but currently the state has obstructed these. Such weakly implemented institutions often lead to unsatisfactory outcomes for different stakeholders. The analysis of institutions created as part of the Treesleeper Eco-camp shows that the institutional performance of Treesleeper was relatively robust before the government grant and consequent upgrade, but changed into a much more fragile institutional status afterwards (cf. Bijsterbosch, Citation2016). A vicious, unsustainable circle of weak institutional processes emerged, with the community no longer truly involved nor informed, and Treesleeper unable to provide benefits, most critically to the community it aimed to serve. Key characteristics of CBT – community control, ownership and participation – have been lost at Treesleeper, which can, at least partly, be explained by contemporary state paternalism.

Still today, the position of Bushmen is often inferior, fitting seamlessly into historical paternalist relations of various kinds. And although the governors these days are evermore black instead of white, this does not seem to make an essential difference, either for the Bushmen or for state officials; colonial and imperialist (development) processes perpetuate today, and state officials (in the case of Treesleeper) are now the new governing superiors. Moreover, at the already small resettlement farm of Tsintsabis other groups who in-migrate seem to take over power and control, leading to an increasing feeling of powerlessness among the Hai//om and !Xun in relation to the other groups (Castelijns, Citation2019; Koot & Hitchcock, Citation2019). If power and control are then also taken away from ‘their own’ projects, such as Treesleeper, paternalism has the effect that they are also dispossessed of their sovereignty.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere gratitude goes to all respondents, to Moses //Khumûb for his assistance and Elvis// Gamaseb for translating interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 We prefer the use of ‘Bushmen’ instead of ‘San’, because most of the Hai//om and !Xun of Tsintsabis explained to us that they prefer this term. We are aware, however, of the colonial, patronizing and derogatory connotations that the term ‘Bushmen’ (and, to a lesser degree, ‘San’ too) can have (see, e.g. Gordon & Douglas, Citation2000). This local preference shows, for example, also at Treesleeper, where the term ‘Bushmen’ was specifically added to the logo of the project by the Hai//om camp manager around 2007–8 (see Koot, Citation2018).

2 Due to inflation and changing currency rates, in March 2016, during the fieldwork period, €1.00 would have been worth N$ 16,76 and at the time of writing, in July 2019, this would be N$ 15,97 (Currency XE, Citation2019).

3 It goes beyond the scope of this paper to analyse all institutional design principles in relation to Treesleeper—for full details see Bijsterbosch (Citation2016).

References

- //Khumûb, M, 2008. Treesleeper Camp development plan. Tsintsabis Trust, Tsintsabis, Namibia.

- //Khumûb, M, 2015. Information for Namibian Planning Commission: Treesleeper Hai//om San community campsite/lodge. Tsintsabis Trust, Tsintsabis, Namibia.

- Agrawal, A & Chhatre, A, 2006. Explaining success on the commons: Community forest governance in the Indian Himalaya. World Development 34(1), 149–66. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.013

- Agrawal, A & Gibson, CC, 1999. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Development 27(4), 629–49. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00161-2

- Barnard, A, 2002. The foraging mode of thought. Senri Ethnological Studies 60, 5–23.

- Becker, CD & Ostrom, E, 1995. Human ecology and resource sustainability: The importance of institutional diversity. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 26(1), 113–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.000553

- Berkes, F, 2004. Rethinking community-based conservation. Conservation Biology 18(3), 621–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00077.x

- Bijsterbosch, M, 2016. Treesleeper Eco-camp: Changing dynamics and institutions in a community-based tourism project in Namibia. MSc thesis, Wageningen University, the Netherlands.

- Blackstock, K, 2005. A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal 40(1), 39–49. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsi005

- Castelijns, E, 2019. Invisible people: Self-perceptions of indigeneity and marginalisation from the Hai//om San of Tsintsabis. MSc thesis, Wageningen University, the Netherlands.

- Cox, M, Arnold, G & Tomás, SV, 2010. A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecology and Society 15(4), 38. doi: 10.5751/ES-03704-150438

- Crawford, SE & Ostrom, E, 1995. A grammar of institutions. American Political Science Review 89(3), 582–600. doi: 10.2307/2082975

- Currency XE, 2019, https://www.xe.com/ Accessed 23 July 2019.

- Dieckmann, U, 2007. Hai//om in the Etosha region: A history of colonial settlement, ethnicity and nature conservation. John Meinert Printing, Windhoek, Namibia.

- Dieckmann, U, 2011. The Hai//om and Etosha: A case study of resettlement in Namibia. In Helliker, K & Murisa, T (Eds.), Land struggles and civil society in Southern Africa. Africa World Press, Trenton, New Jersey, pp. 155–90.

- Dieckmann, U, Thiem, M, Dirkx, E & Hays, J, 2014. “Scraping the pot”: San in Namibia two decades after independence. Legal Assistance Centre, Windhoek.

- Duffy, R, 2006. The politics of ecotourism and the developing world. Journal of Ecotourism 5(1–2), 1–6. doi: 10.1080/14724040608668443

- Du Toit, A, 1993. The micro-politics of paternalism: The discourses of management and resistance on South African fruit and wine farms. Journal of Southern African Studies 19(2), 314–36. doi: 10.1080/03057079308708362

- Ensminger, J, 1992. Making a market: The institutional transformation of an African society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Fanon, F, 1952. Black skin, white masks. Pluto press, London.

- Ferguson, J, 1990. The anti-politics machine: “Development” and bureacuratic power in Lesotho. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Ferguson, J, 2006. Global shadows: Africa in the neoliberal world order. Duke University Press, London.

- Friedman, JT, 2011. Imagining the post-apartheid state: An ethnographic account of Namibia. Berghahn, New York.

- Gargallo, E, 2010. Serving production, welfare or neither? An analysis of the group resettlement projects in the Namibian land reform. Journal of Namibian Studies 7, 29–54.

- Garland, E, 1999. Developing Bushmen: Building civil(ized) society in the Kalahari and beyond. In Comaroff, JL & Comaroff, J (Eds.), Civil society and the political imagination in Africa: Critical perspectives. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 72–103.

- Gibbon, P, Daviron, B & Barral, S. 2014. Lineages of paternalism: An introduction. Journal of Agrarian Change 14(2), 165–89. doi: 10.1111/joac.12066

- Gordon, R & Douglas, S, 2000. The Bushman myth: The making of a Namibian underclass. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado.

- Haller, T & Galvin, M, 2008. Introduction: The problem of participatory conservation. In Galvin, M & Haller, T (Eds.), People, protected areas and global change: Participatory conservation in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Europe. University of Bern, Bern, pp. 13–34.

- Harring, SL & Odendaal, W, 2002. “One day we will all be equal … ”: A socio-legal perspective on the Namibian land reform and resettlement process. Legal Assistance Centre, Windhoek, Namibia.

- Hohmann, T, 2003. San and the state: An introduction. In Hohmann, T (Ed.), San and the state: Contesting land, development, identity and representation. Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, Köln, pp. 1–35.

- Hüncke, A & Koot, S, 2012. The presentation of Bushmen in cultural tourism: Tourists’ images of Bushmen and the tourism provider’s presentation of (Hai//om) Bushmen at Treesleeper Camp, Namibia. Critical Arts 26(5), 671–89. doi: 10.1080/02560046.2012.744722

- Ingram, VJ, 2014. Win-wins in forest product value chains? How governance impacts the sustainability of livelihoods based on non-timber forest products from Cameroon. African Studies Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands.

- Itamalo, M, 2017. Tsintsabis a settlement with two feuding chiefs. The Namibian, 7 March, p. 6.

- Koot, S, 2012. Treesleeper Camp: A case study of community tourism in Tsintsabis, Namibia. In Schmidt, A & Van Beek, W (Eds.), African Hosts and their guests: Cultural dynamics of tourism. Boydell & Brewer, New York, 153–75.

- Koot, S, 2015. White Namibians in tourism and the politics of belonging through Bushmen. Anthropology Southern Africa 38(1&2), 4–15. doi: 10.1080/23323256.2015.1011343

- Koot, S, 2016a. Contradictions of capitalism in the Kalahari: Indigenous Bushmen, their brand and baasskap in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 28(8&9), 1211–26. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1158825

- Koot, S, 2016b. Perpetuating power through autoethnography: My research unawareness and memories of paternalism among the indigenous Hai//om in Namibia. Critical Arts 30(6), 840–54. doi: 10.1080/02560046.2016.1263217

- Koot, S, 2018. The Bushman brand in southern African tourism: An indigenous modernity in a neoliberal political economy. Senri Ethnological Studies 99, 231–50.

- Koot, S & Hitchcock, R, 2019. In the way: Perpetuating land dispossession of the indigenous Hai//om and the collective action law suit for Etosha National Park and Mangetti West, Namibia. Nomadic Peoples 23(1), 55–77. doi: 10.3197/np.2019.230104

- Lapeyre, R, 2010. Community-based tourism as a sustainable solution to maximise impacts locally? The Tsiseb Conservancy case, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 757–72. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2010.522837

- Legal Assistance Centre, 2006. ‘Our land they took’: San land rights under threat in Namibia. Legal Assistance Centre, Windhoek.

- Master of the High Court, 2004. Deed of Trust, Tsintsabis Trust. Windhoek, Namibia.

- Mowforth, M & Munt, I, 2003. Tourism and sustainability: Development and new tourism in the Third World. Routledge, London.

- Novelli, M & Gebhardt, K, 2007. Community based tourism in Namibia: “Reality show” or “window dressing”? Current Issues in Tourism 10(5), 443–79. doi: 10.2167/cit332.0

- Ostrom, E, 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Ribot, J, Chhatre, A & Lankina, T, 2008. Introduction: Institutional choice and recognition in the formation and consolidation of local democracy. Conservation and Society 6(1), 1–11.

- Saarinen, J, 2010. Local tourism awareness: Community views in Katutura and King Nehale Conservancy, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 713–24. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2010.522833

- Shifidi, I, 2010. Small builders in the Namibian construction sector: Opportunities, challenges and support strategies. Economic Research Southern Africa, Cape Town.

- Suzman, J, 2001. An assessment of the status of the San in Namibia. Legal Assistance Centre, Windhoek.

- Sylvain, R, 2001. Bushmen, boers and baasskap: Patriarchy and paternalism on Afrikaner farms in the Omaheke region, Namibia. Journal of Southern African Studies 27(4), 717–37. doi: 10.1080/03057070120090709

- Troost, D, 2007. Community-based tourism in Tsintsabis: Changing cultures in Namibia. BSc thesis, InHolland University of Applied Sciences, Haarlem, the Netherlands.

- Van Beek, W, 2011. Cultural models of power in Africa. In Abbink, J & De Bruijn, M (Eds.), Land, law and politics in Africa: Mediating conflict and reshaping the state. Brill, Leiden, the Netherlands, pp. 25–48.

- West, P, 2016. Dispossession and the environment: Rhetoric and inequality in Papua New Guinea, Colombia University Press, New York.

- Wilmsen, E, 1989. Land filled with flies: A political economy of the Kalahari. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Wilshusen, P, 2014. Capitalizing conservation/development: Dissimulation, misrecognition, and the erasure of power. In Büscher, B, Dressler, W & Fletcher, R (Eds.), Nature™ Inc.: Environmental conservation in the neoliberal age. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp. 127–57.