ABSTRACT

This paper examines how capabilities inequality is stabilised through its consequences on those at both ends of the distribution. It outlines the development of the balance model, which is argued to help highlight these consequences. Specifically, how adverse environments associated with lack of access to resources and poor treatment can lead to internal consequences which further corrode capabilities. At the same time, denial of this corrosion or its importance is critical for those who benefit from the inequality. To avoid moral constraints being triggered it is important, necessary even, for them to see those who suffer as outside of their moral universe, or their suffering to be in no way associated with their advantage. Corrosion and denial work to stabilise the system. For those in the middle of the distribution, they may work to do so in combination. Appreciating these internalised consequences is key to addressing inequality in South Africa.

1. Introduction

Measured in terms of income, wealth or opportunity, South Africa is among the most unequal countries in the world (Klasen et al., Citation2016; Wittenberg & Leibbrandt, Citation2017). Despite progressive interventions, notably progressive income tax, social grants and provision of basic services, and some success, inequality remains stubbornly high (Hundenborn et al., Citation2018; Maboshe & Woolard, Citation2018). A wealth of scholarship on inequality in South Africa has led to a clearer understanding of its origins, and the structural challenges, especially in the labour market and education system, which maintain it (Van der Berg, Citation2011; Leibbrandt et al., Citation2018). The literature has also highlighted the consequences of inequality, including for social cohesion, and how a lack of social cohesion hinders efforts to address inequality (Palmary, Citation2015; Abrahams, Citation2016; David et al., Citation2018).

Here I argue that if we are to address inequality in South Africa we would do well to appreciate the symbiotic relationship between the structural drivers and the social consequences. The social consequences, of which social cohesion is an example, as are racism and sexism, flow, via inequality, from the structural drivers. At the same time, they help maintain and even strengthen those structural drivers. As a result, these social ills are valuable to those who benefit from the unequal system because they help them maintain that system.

This argument emphasises the need for structural change, not that further emphasis was needed. However, it also suggests that those with the power to make that change are unlikely to drop the prejudices which prevent them from seeing the urgent need for such change. This implies that change must be forced by those who do not benefit from the current situation. But, I suggest, this is unlikely to happen because of the debilitating consequences of inequality for those at the wrong end of the distribution. In short, South Africa’s unequal distribution of income, wealth and opportunity is self-perpetuating and unlikely to change, at least in the near term. Unless, that is, we identify ways to disrupt the mechanisms through which inequality perpetuates itself. This requires a better understanding of these mechanisms, which I argue requires a holistic view of the individuals involved, particularly how they make decisions.

In developing this holistic view, I question three commonly held assumptions regarding human decision making. These, I suggest, hinder our ability to identify many of the consequences for decision making of interactions between people and between people and their environment, and in so doing mask how unequal systems become self-perpetuating through their influence on these interactions. The first assumption is that individuals maximise utility, the second that human needs are hierarchical, and the third, that you can understand decision making without an appreciation of history (individual or social).

I argue that it is more appropriate, and helpful, to assume that decision making is shaped by the pursuit of balance, across multiple, at times competing, motives. Further, that our needs are non-hierarchical. And finally, that our motives, and our approach and ability to balance them, are shaped over the life-course, in interaction with our historically contingent environment.

I refer to these assumptions collectively as the balance model. This model provides a framework within which relevant insights from neurology, cognitive psychology and sociology can be incorporated. This allows for the development of the holistic view of individuals required. I use the balance model here to highlight two inequality-stabilising influences on decision making: denial of responsibility and corrosive consequences.

Denial of responsibility is more common among those higher up the distribution. It helps them to live comfortably, untroubled by the situation of others. Shutting off the emotional response to the plight of those below them in the distribution has a stabilising effect. Corrosive consequences are more common among those at the wrong end of the distribution. They are responses to the environment which worsen the situation for the individual and perpetuate the inequality through their damaging influence on decision making.

While denial and corrosion may be more common at opposite ends of the distribution, they may co-occur. Decisions, particularly of those in the middle of the distribution, may be influenced by both.

The arguments here are particularly relevant in South Africa, given the extremeness of our inequality, its connection to poverty and the history of injustice which underpins both (Leibbrandt et al., Citation2018). It is not explored, but many of these arguments are likely to be relevant in other highly unequal contexts, particularly other post-colonial settings.

2. Inequality of what?

In South Africa, many things are distributed unequally: income, wealth, land, healthcare, education, access to legal protections, respect and so on (Posel & Casale, Citation2011; Leibbrandt et al., Citation2018). Many of these are correlated with income, and addressing income inequality would likely reduce other inequalities. Inequality in this paper, however, is discussed primarily in terms of capabilities. This because wellbeing is constrained or facilitated by more than income, but also because the capabilities approach focuses on choice, as does this paper (Sen, Citation2003).

Nussbaum’s Capabilities framework is useful here (Nussbaum, Citation2001). She differentiates between basic, internal and combined capabilities. Basic capabilities refer to the ‘innate equipment of individuals that is the necessary basis for developing the more advanced capabilities’ (Nussbaum, Citation2001:84). Internal capabilities are ‘developed states of the person herself … sufficient conditions for the exercise of the requisite function … mature conditions of readiness’ (Citation2001:84). Nussbaum argues that the key feature of internal capabilities is that they require the support from the ‘surrounding environment’ to develop. For internal capabilities, such as the internal capability to exercise political choice, to be realised, it must be combined with ‘suitable external conditions’ (Citation2001:85). It then becomes a combined capability.

Nussbaum used this framework to discuss adaptive preferences: situations where rights violations and/or poor treatment are not seen as such by the individuals who experience them. People may even report high levels of life satisfaction despite objectively harsh circumstances. Sen raises the possibility of a happy slave as an extreme example (Sen, Citation1999).

Adaptive preferences or false consciousness, as they are sometimes called, are one example of what I refer to here as a corrosive consequence. Others include consequences which hinder the development of basic capabilities – particularly through the physical consequences of early-life disadvantage. The importance of the surrounding environment in developing even basic capabilities is missed by Nussbaum. Corrosive consequences also include a range of psychological consequences of adversity, in addition to false consciousness, which hinder the development of internal capabilities, but have not been examined within the capabilities framework.

3. The balance model

The model is based on three assumptions: the pursuit of balance, non-hierarchical needs and historically contingent decision making. It is developed to provide a framework within which to organise insights from multiple disciplines. The model is then used to highlight consequences, for decision making, of unequal distributions.

3.1. Assumption 1: individuals seek balance

The balance assumption is that people have multiple irreducible motives. The stronger a motive, the more pressure it puts on the individual to act to respond to that pressure. The individual seeks to allocate resources, including their attention and effort, to keep the pressure to act to a minimum.

There is a long history of debate in economics about the number of motives and maximisation (Hindess, Citation2014). This debate has focused on whether people are purely self-interested, a critical question in economics. Various versions of the argument that individuals have moral motives and self-interested motives have been outlined. The response has been that at some point the individual must decide between them, and therefore must have a higher order motive which dictates action. The question then turns to whether that higher-order motive can rightly be called self-interested. With this debate in mind, I acknowledge that you could construct a utility function which ‘maximises balance’ and produce the same results. But I would argue, as Sen so powerfully did in 1977, that the concept of utility needed to do so is impossible to link back to self-interest (Sen, Citation1977).

Support for the assumption that people have multiple irreducible motives can be found in neurology (Sapolsky, Citation2017) and cognitive psychology (Fodor, Citation1983). Studies in neurology suggest the brain does not operate as one big cost–benefit calculator. Different regions, or rather different networks of brain regions, activate in different situations. Networks are associated with different kinds of pressure/motives to act, think hunger, fear, excitement, anticipation as examples. More than one network may be activated at a given time, and they may push in different directions. Higher order brain regions and functions are then called into play, including the prefrontal cortex, to arbitrate. This leaves open the possibility of considered action and a place in decision making for a cost–benefit calculator. Similarly, in cognitive psychology, the idea of modular cognition and central processing has received some support, although with debate among its proponents regarding the extent of the modularity (Fodor, Citation1983; Pinker, Citation1999; Fodor, Citation2000). Essentially the (contested) argument is that different modules have, through natural selection, evolved to address specific challenges, which are triggered depends on how the situation is perceived (Pinker, Citation1999).

Support for the assumption that individuals have limited attentional resources and preoccupation can lead to us missing/ignoring other things, can be found in psychology and behavioural economics, where it is referred to as cognitive load or bandwidth (Mani et al., Citation2013).

The balance assumption makes it easy to see a number of important decision influencing factors, such as perception (including framing), limited attention, internal conflict and constraints, and associated attitudes to information.

Framing refers to how things are presented, but the important thing is how they are perceived. With the balance assumption, the importance of perception is clear. How a situation is perceived influences which motives are triggered, and thereby influences the decision made. Many things influence perceptions, from how good your sight is, to how you have come, over time, to understand the world and your place within it. This latter influence is key to explaining the corrosive consequences discussed below.

The balance assumption highlights how strong motive, demanding lots of attention can lead to other motives being ignored (given attention is assumed finite). This links to corrosive influences associated with preoccupation caused by the need to direct so much attention to the challenges of living in adversity.

With the balance model, because motives are assumed irreducible, we can conceptualise a situation where a strong motive acts as a constraint, preventing a response to another motive. Trade-offs are possible up to a point, but at times only an action which responds to a particular motive will do. The possibility of trade-offs exists in every decision-making model. The possibility of constraints (limits to the trade-offs) does not. Unfortunately, unpleasant examples illustrate the difference between trade-offs and constraints best. For the vast majority of people, the revulsion of paedophilic acts would constrain them from committing them, no matter what they were offered in return. Unless what they were offered were of the same kind of thing, for example, avoiding abuse of multiple other children; even that might not be enough.

A critical implication of competing motives acting as constraints is what it suggests regarding people’s attitudes towards information. An individual may want to avoid some constraining motive being triggered. There are things that they just don’t want to know. Enter denial and rationalisation more generally. The balance model opens the door to explicit consideration of self-manipulation to avoid moral constraints. Racism, sexism and othering in general are useful tools if you want to avoid triggering a moral obligation to help other people, leaving you free to pursue narrower interests.

3.2. Assumption 2: individuals have non-hierarchical needs

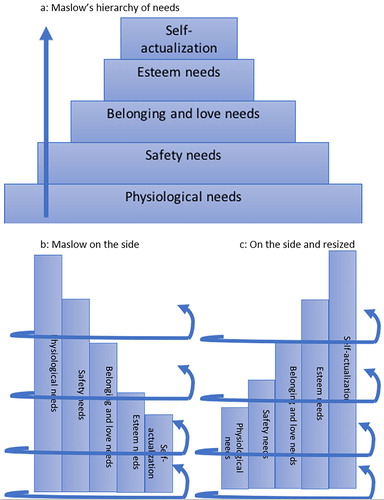

The most famous conceptualisation of needs as hierarchical is provided by Maslow (Citation1943). His memorable pyramid depicts how individuals start with basic physiological motives, moving up through the hierarchy to safety, belonging and love, esteem and finally to self-actualisation – (a).

The assumption here is that you would get a more accurate reflection of human needs if you turn Maslow’s pyramid on its side – see (b). Individuals need a little of everything, then a little more of everything. We can still incorporate Maslow’s point that you may invest more in the pursuit of ‘higher order’ needs once more basic needs are met, by resizing the sections of his triangle – see (c). This, however, does not preclude higher order motives being important at all times. A similar point is made by Max-Neef et al (Citation1992) in their outline of Human-Scales Development.

The implication of the non-hierarchal assumption is that those living in adversity have and are motivated by higher-order needs. Accepting Maslow’s categories for the moment, this implies that those living in deprivation are still interested in belonging, esteem and self-actualisation. They may sometimes be pre-occupied with physiological needs, but it does not mean the others are ever absent.

Powerful evidence in support of the non-hierarchical needs assumption comes from research on early childhood development, as young children clearly have a critical need for ‘higher order’ inputs. Without love and a sense of belonging, many young children simply fade away. This is one of the reasons why institutional care is so damaging (Berens & Nelson, Citation2015). Further support for the assumption comes from the work on poverty and shame. In cross country comparisons, Walker and colleagues found that despite differences in material circumstances, people living in poverty felt shame (Walker et al., Citation2013). Shame is not a result of unmet lower order needs, it is a result of unmet higher order needs.

If belonging, esteem and self-actualisation are important, even in contexts of material adversity, a lack of opportunity to realise these motives is potentially costly, corrosive even. This provides a link to the work of Fanon, Freire and Biko, and those who have developed their arguments (Fanon, Citation1965; Freire, Citation1968; Biko, Citation1978; Prilleltensky & Gonick, Citation1996). They highlight how poor treatment, particularly dehumanising treatment and contexts, take their toll (over time, see assumption 3) on individuals living in adversity. More broadly it links to the work of Hegel, particularly the areas of his work which have more recently been developed by Honneth (Citation2004). This area highlights the importance of recognition at the family, civil and social levels in shaping people’s perceptions of themselves and their place in society. Recognising the non-hierarchy of needs allow us to draw in this literature, and highlight the potentially corrosive impact on decision making of negative interactions with others, and how such corrosive consequences stabilise unequal distributions of capabilities (particularly through their influence on internal capabilities). However, to appreciate these influences more fully, their influence on individuals over time must be considered.

3.3. Assumption 3: historically contingent decision making

Individual’s perceptions and responses are shaped over time. Here I consider three mechanisms: psychological internalisation; physical internalisation and historically contingent nature of the present context. These three link closely with Nussbaum’s Capabilities Framework (Citation2001). Psychological internalisation relating to the development of internal capabilities; physical internalisation to the development of basic capabilities and the present context as a critical component of combined capabilities.

Psychological internalisation includes skills development through to the adoption (to varying degrees) of social norms. It includes learning, from early interactions with parents, to schooling, to work experience, to learning through interactions with others more broadly. There is a wealth of literature from developmental psychology outlining the numerous ways in which experiences of the world shape the way in which individuals think about and respond to that world. A summary of this literature is beyond the scope of this paper. Interested readers are referred to Sameroff’s Unified Theory of Development which provides a heroic attempt to draw the insights of this field together (Sameroff, Citation2010).

There is overlap here with assumption 2, as psychological internalisation includes influences on the development of internal capabilities, such as the corrosive influences discussed in relation to gender by Nussbaum (Citation2001), race by Biko (Citation1978), broader recognition by Honneth (Citation2004) and adversity by Freire (Citation1968). These occur overtime, but they occur because ‘higher order’ needs are always essential.

An individual’s experiences of and interact with their environment shapes them physically, i.e. they influence the development of basic capabilities. It is now well established that nature and nurture work together, including through gene-environment interactions, to shape long-term outcomes (Essex et al., Citation2013). For example, early life adversity has been linked to reduced cognitive function, leading to poorer school outcomes and decreased adult earnings (Shonkoff et al., Citation2012). The frequency of the physical internalisation of interactions acute in early childhood and falls dramatically after adolescence, as the brain fully matures in the early twenties (Arain et al., Citation2013). The possibility of later life influences remains, through poor health, injury and old age (Johnson, Citation2001).

The third individual mechanism through which history shapes decision making considered here is the feedback loop. A teenager may experiment with drugs and become addicted, increasing the likelihood of further drug use. This may change their opinion of themselves, as they start to see themselves as a drug user, influencing a range of decisions. Others could start to see the individual as a drug user and change their treatment of them accordingly, possibly leading to imprisonment, with obvious consequences for decision making and capabilities.

The broader environment with which individuals interact, including the institutions which shape their interactions with others, are historically contingent. An individual’s decision making is influenced by their own past and the past of the environment with which they interact. Over time they internalise aspects of that environment, making the two influences difficult to separate.

3.4. An emerging framework: the assumptions in combination

The balance assumption provides a representation of how individuals make decisions: they allocate attention and effort to promote balance across multiple motives. Any of these multiple motives may be triggered at any time. The strength of motives, the ability to balance across them and what triggers them are all calibrated over time.

The non-hierarchical and historically contingent assumptions add greater depth to the implications of the balance assumption. Past experiences influence how things are perceived, and therefore which motives are triggered. Individuals have to allocate attention across motives responding to multiple different needs rather than working their way through a hierarchy. Similarly, internal conflict can involve multiple different types of motives/needs, at any time; deciding to beg for food remains a humiliating experience, even for the starving. The ways in which individuals manage internal conflict and associated internal constraints are shaped overtime.

The central role of perception highlights the role of others in shaping our decisions. Other people influence our perceptions. There is a lot to make sense of in the world, and how other people act, including how they treat us, provides a useful guide. Interpreting the actions of others helps us understand the world and our place in it, and therefore, influences our decisions. Other people shape our umwelt.

4. Balance and inequality

The balance model makes it easy to highlight two consequences of highly unequal capabilities distributions, and how they stabilise the unequal capabilities’ distributions that cause them. The first is denial of responsibility. Denial is a tool used by those who benefit from unequal, or more precisely, unfair, distributions to protect themselves from moral constraints which would otherwise be triggered, thereby stabilising the distribution. The second is corrosion. Corrosion refers to consequences of unequal distributions which corrode people’s capabilities (basic, internal and combined), including the capability to challenge the system. While denial and corrosion are likely to disproportionally affect individuals at opposite ends of the capabilities distribution, they can occur in the same individual, this possibility is discussed.

4.1. Denial of responsibility

The balance model, in particular the balance assumption, allows for the possibility that individuals have internal constraints. That is, that they have motives which limit the extent to which they can follow other motives. Examples include risk aversion and moral constraints. In more traditional decision models, constraints are simply strongly held preferences. This, however, fails to capture the texture of a constraint. An individual with a strongly held preference wants to act in accordance with that preference, they do not look for ways around it.

In the balance model, constraining motives put certain options off limits, even if there are no external constraints to taking these options. Critically, this situation leaves the individual with a choice: act in accordance with the constraint, or try to rationalise it away. The scope of rationalisation may be limited, but the more convincing the rationalisation – at least to the individual themselves – the more power it has to weaken constraints.

Constraints of different types may exist, but the possibility of moral constraints, rather than moral preferences, has particular significance here. Moral constraints can be worked around and possibly rationalised away. The key is to change how the situation is perceived and what this perception implies. This includes actively working to change how we perceive others and as a result, what our moral obligation to those others is.

The stereotype content model (Cuddy et al., Citation2008) provides a useful framework to explain an example of rationalising away a moral constraint. The model proposes that individuals group other people along two dimensions: competency and warmth See for the resulting 2-by-2 table. Other people fall into one of the boxes: high competency high warmth (HH), high competency low warmth (HL), low competency high warmth (LH) and low competency low warmth (LL). HH are the in-group, the us. We are more likely to be forgiving towards individuals in this group, to excuse their actions when they transgress and seek to please them. HL are the competition, the other we respect the abilities of, but don’t like. The most famous example being Jewish people in Nazi Germany. LH include people such as intellectually impaired children. LL include people like the homeless.

Table 1. Stereotype content model.

What Cuddy et al. suggest is that what you consider to be your moral responsibility to others is heavily influenced by which group you perceive them to be in. You have a high level of responsibility to HH and near none to LL, with the other two groups falling somewhere in-between. The frightening part comes when we observe how people shift others from one group to another so that their moral responsibility towards them is reduced. Sapolsky asks us to consider the different treatment of Roma and Jewish people in Nazi Germany (Sapolsky, Citation2017). The former were already considered by the Nazi’s as LL, leaving them free to kill them without delay. The latter, Sapolsky argues, started as HL and had first to be pushed to LL. Humiliation was a necessary step, it allowed the Nazis to weaken the hold their moral constraints, which applied to HL but not LL.

Genocide provides an extreme example, but there are plenty of other examples of how some exclude others from their moral universe by finding ways to think of them as less deserving or less human. Racism, sexism and the caste system have all been used, and are still used, to this end.

In South Africa, the highly unequal distributions of income and capabilities leave many people living very difficult lives. For those higher up these distributions, it would be uncomfortable to acknowledge that these distributions are unfair and that those who suffer as a result are within their moral universe. They may even feel morally compelled to act. Those who can convince themselves that the distributions are fair and/or that those who suffer are less human and less deserving of moral recognition, will feel less pressure to act. The focus here is on unfairness, rather than inequality, because recent research suggests that people have a high tolerance of inequality, but a strong aversion to unfairness (Starmans et al., Citation2017).

It is through the lens of moral constraints and pressures to act that we should understand racism, sexism and class based dehumanising in South Africa. Rationalisations for denying the humanity of others, and therefore denying your obligations towards them, are critically important to those who use them. It is not just a matter of them holding unpleasant beliefs. If it were, appeals for them to re-examine these beliefs and recognise a shared humanity may have some success. They are positions which are defended because conceding ground would be too costly, it could trigger a moral compulsion to push for change. It is on these grounds that Desmond (Citation1978) argued that Apartheid could not be reformed into a kinder version, as the unkindness was required to justify the system. Similarly today, the structural drivers which benefit those at the top, require the dehumanising of those at the bottom, to a lesser extent than during Apartheid, but required nonetheless.

System justification theory provides a similar argument: advantaged individuals are assumed to desire a positive self- and group image, and a positive image of the system which benefits them, and are therefore motivated to adopt arguments that justify the status quo (Jost et al., Citation2004). While similar, the use of the term denial is intended to suggest something stronger than a desire, and less conscious. The denial of responsibility discussed here is closer to the way in which Stan Cohen, in his wonderful book, States of Denial, discusses multiple examples of how individuals appear to self-manipulate, how they avoid knowing, because knowing would necessitate responding (Cohen, Citation2013).

4.2. Corrosive consequences

Corrosive consequences are internalised consequences of living in, or having lived in, an environment which erodes, through impacts on basic and internal capabilities, people’s ability to live the life they have reason to value. This includes corrosion resulting from interactions with others and the corrosion of people’s ability to reason what they should value. This latter inclusion may appear to blame those at the wrong end of the distribution for their situation. It does. This will be discussed below.

The concept of corrosive consequences flows from the balance model. It draws on the assumption decision making is shaped over time through internalisation of contextual influences (assumption 3), and that decisions, even for the most disadvantage, are influenced by needs of many different types (assumption 2). It also draws on the assumption that attention is finite, i.e. that there is a corrosive influence stemming from preoccupations associated with living in adversity.

The concept of corrosive consequences draws on the idea of corrosive disadvantage proposed by Wolff and De-Shalit (Citation2007). Corrosive disadvantage refers to situations where one kind of disadvantage, say homelessness, leads to other kinds of disadvantage, say difficulty in gaining employment. Corrosive consequences are similarly concerned with how one kind of disadvantage increases the risk of another, but have a narrow focus, in some sense they are a sub-set as they focus only on disadvantage associated with internalisation. In the homelessness example, the corrosive disadvantage may stem from the need to have an address for employment application (the context), a corrosive consequence could stem from the loss of self-esteem (internalisation of context).

Here I discuss two routes, relevant in South Africa, from inequality to corrosive consequences. The first is the internalisation of adversity associated with poverty. Other things being equal, greater inequality means greater poverty. Consequences of poverty are, therefore, at least partly, consequences of inequality. The second is unfairness and unfair treatment. In South Africa, given that our unequal distributions were created by oppressive colonial and Apartheid systems, the link with unfairness and unfair treatment is acute.

The corrosive consequences of poverty and unfairness are myriad. It is not possible to discuss them fully here. However, highlighting some of the critical consequences, and linking them to the balance model, already provides a clear indication of how poverty and unfairness corrode, though hindering the development of basic and internal capabilities, the ability of people to live the life they have reason to value. Moreover, how these corrosive consequences stabilise the unequal capabilities distributions which cause them.

Deprivation associated with poverty can impact on an individual’s ability to adjudicate between conflicting movies via its impact on neurological development i.e. via its impact on the development of basic capability. For example, material deprivation, particularly if experienced early in life, can hinder brain development, through inadequate nutrition, lack of early stimulation, higher incidence and severity of infection and higher risk of abuse because of weak child protection systems (Shonkoff et al, Citation2012). Constraints on neurological development lead to poorer cognitive development, including executive function and development of socio-emotional skills. Cognition is important in understanding problems and executive function is important in self-control, i.e. managing internal conflict. Socio-emotional skills are important for navigating society. These all have obvious corrosive impacts (Heckman et al., Citation2006). Firstly, they are associated with poorer education outcomes. Secondly, they influence later life risk behaviours. Thirdly, they can lead to poorer decision making in general.

In adults, poverty can hinder cognitive function because of preoccupation with daily challenges. With limited attentional resources to allocate (bandwidth), preoccupation with the difficulties associated with poverty reduces the bandwidth available to be allocated to other motives and associated tasks. Such preoccupation has been shown to reduce performance in cognitive tests (Mani et al., Citation2013).

The corrosive consequences of adversity in early life and preoccupation associated with adversity at any life stage occur through biological mechanisms. There are also psychological mechanisms (and those which work through psychological to the physical (Marmot, Citation2005)). These are similar to the hindrances to the development of internal capabilities discussed by Nussbaum (Citation2001) in relation to gender, but as argued in relation to non-hierarchical needs, there are many other examples. Poverty, unfairness and unfair treatment can influence perception, including self-perception, in corrosive ways. Negative social norms relating, for example, to race and gender, may be internalised, including in heuristics (‘university is not for people like me’). Living in poverty and being treated unfairly can shape an individual’s perception of themselves and their place in society, including their ability to influence society. These are the corrosive consequences discussed by Fanon, Biko, Freire and in the literature on internalised oppression (Prilleltensky & Gonick, Citation1996). Similarly, the work of Honneth (Citation2004) highlights how, through interactions with others, people come to develop their understanding of themselves, and how they should relate to others, with implications for how much agency they feel they have. Corrosive consequences include learned helplessness, apathy, false consciousness, destructive anger and low self-esteem, among others. The work on poverty and shame, suggests similar corrosive consequences such as withdrawal, self-loathing and reduced personal efficacy (Walker et al., Citation2013). These corrosive consequences are a result of unmet ‘higher order’ needs, such as the need to be treated with dignity by others, among people who may also not be meeting their lower order needs.

Corrosive consequences are likely to cluster within individuals, both because they may have common causes, but also because one may lead to another. They may also cluster in particular life stages, with devastating consequences. Adolescence is one such life-stage (Dahl, Citation2004). Decisions made during this period often have life-long implications: for example, decisions relating to schooling, substance use and sexual behaviour. Corrosive consequences in this life stage act to amplify the risks of long-term negative harm.

Highlighting internalisation and the role of individuals’ decisions in worsening their own outcomes and perpetuating an unfair system may come across as victim blaming. However, if we wait for those who are responsible for the unfair distribution to fix it, we will be waiting a long time. Identifying ways in which those who suffer from unfair distributions are complicit, is to identify ways in which they can act to change the situation. This is the way in which Biko and Fanon identified ways in which the oppressed could develop their own power.

4.3. Denial and corrosion in combination

It would be a mistake to present the South African situation in binary terms: as those who have and are in denial, and those who don’t have and are suffering corrosive consequences. Firstly, not everyone who has is in denial, nor is everyone who doesn’t have suffering from corrosive consequences. Some people at the top of the distribution are sociopaths (they don’t have constraints) and others want to see change, even if it worsens their relative position. While at the other end of the distribution, biological and psychological differences between individuals, and different combinations of adversity and support systems, lead to different experiences and interactions, and therefore, different outcomes. Secondly, corrosive consequences and denial can occur in combination. Arguably, it is this combination that has the greatest stabilising effect.

Consider the corrosive influence on self-image described by Biko. He described an individual angry at their treatment, at the unfairness of their situation, but who feels powerless to challenge the system. Critically, however, he also suggested that this anger may be vented in the wrong direction:

Reduced to an obliging shell, he looks with awe at the white power structure and accepts what he regards as the inevitable position. Deep inside his anger mounts at the accumulating insult, but he vents it in the wrong direction – on his fellow man in the township, on the property of black people. (Steve Biko, Citation2015)

The most disadvantaged in South Africa have little contact with the most advantaged. The dehumanising treatment many endure is at the hands of those who are only a little higher up in the distribution than they are. This has a doubly stabilising effect. Firstly, it divides these two groups. Secondly, it provides the population coverage of dehumanising treatment of the most disadvantaged – i.e. it exposes millions to corrosive interpersonal interactions, rather than limiting those interactions to the thousands who have direct contact with the wealthy. Without it, the corrosive consequences of dehumanising treatment, and their stabilising effect, would be far less common.

4.4. From stabilising to de-stabilising

The above analysis suggests that to begin to address inequality, you have to address denial, corrosion or both. I do not know how to do this. The paper is primarily diagnostic, outlining what I see as challenges. How to address these is an open question, which, I would argue, requires much more attention. Some initial thoughts follow.

Denial is a tough nut to crack. It is valuable and so it is defended. The one possibility is to identify ways to alter the environment such that the denial is no longer useful. Consider the decline in overt racism before and after the 1994 transition. Arguably the domestic and international pressure on the Apartheid state made maintaining the system as it was no longer profitable, at least for an elite. The shift to a negotiated transition with its protection of economic interests allowed for a shift in the intensity of the racist justifications.

The Black Consciousness Movement aimed to address the corrosive consequences of the Apartheid state. Perhaps the state murdered Biko because they saw the potentially destabilising impact such a movement could have. More recently, a range of small-scale interventions have been developed along similar lines, involving small groups providing support and a sense of empowerment in the face of a potentially corrosive environment (Mahali, Citation2017). While these interventions show promise, and may have the potential to address some of the corrosive psychological consequences of inequality, they do little to address the physical, and seem too small to make a difference. It is, however, worth asking if they could be expanded, both in terms of the corrosive consequences they address and in their scale.

5. Conclusions

Capabilities inequality takes its toll. Adverse environments associated with lack of access to resources and poor treatment can hinder the development of basic and internal capabilities. Given the role of these capabilities in decision making, they can, in turn, lead to consequences which further corrode capabilities. Critical among these corrosive consequences is the corrosion in the capability to fight for system change.

At the same time, denial of these corrosive consequences or their importance is critical for those who benefit from the inequality. To avoid moral constraints being triggered it is important, necessary even, for them to see those who suffer as outside of their moral universe, or their suffering to be unrelated to their advantage. Corrosion and denial work to stabilise the system. For some they work in combination. The corrosive consequences experienced by those in the middle may lead them to engage in displacement aggression, treating badly those below them in the distribution. They provide the means through which the denial of those at the top can lead to the widespread potentially corrosive treatment of those at the bottom.

The use of the capabilities approach, and in particular Nussbaum’s framework of basic, internal and combined capabilities, proved useful in the discussion of corrosive consequences. In this framework, the corrosive consequences for decision-making capacity are identified as costly, even if they have no material consequences. To fully appreciate the corrosive consequences of inequality, the framework did, however, require extension. Hereto ignored is that basic capabilities are, similar to internal capabilities, shaped by relationships and other interactions with the environment. The capabilities framework was less useful when discussing decision making at the upper end of the distribution. This observation (useful at one end of the distribution by not much at the other), echoes the conclusions of Burchardt & Hick’s (Citation2018) in their recent discussion of the application of the capabilities approach to studies of inequality.

Central to my argument is the position that to understand people’s decisions, we must try to understand people’s interactions with others, past and present, and how they respond to those interactions. From the relationship a new-born child has with its mother, through to the way in which society attaches values to certain types of people, relationships and interactions between people are central to shaping who we are. Individuals do not pass through life simply bouncing off one another. Interactions with other people change us. They change how we see ourselves, how we see other people and how we see our place within society. At times, they even change our bodies, including our brains. In South Africa, a country shaped by a history of confrontational and dehumanising interactions, it is unsurprising that there would be enduring harm from these interactions. What I have argued here is that this harm is internal as well as external. Concentrating only on addressing the external harm has not worked well. Biko would not be proud.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the reviewers for helpful, if challenging comments. Thanks also to Dori Posel for insightful comments on a very early version, and to Kathryn Watt for help finalising the submission. Finally, the author acknowledges the significant contribution of Candice Moore though her comments on and discussion of numerous drafts. Thanks also to Tony Barnett and Dori Posel for insightful comments on very early versions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, C, 2016. Twenty years of social cohesion and nation-building in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 42(1), 95–107. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1126455

- Arain, M, Haque, M, Johal, L, Mathur, P, Nel, W, Rais, A, Sandhu, R & Sharma, S, 2013. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 9, 449.

- Berens, AE & Nelson, CA, 2015. The science of early adversity: Is there a role for large institutions in the care of vulnerable children? The Lancet 386(9991), 388–98. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61131-4.

- Biko, SB, 1978. Black consciousness and the quest for a true humanity. Ufamu: A Journal of African Studies 8(3), 10–20.

- Biko, SB, 2015. I write what I like: Selected writings. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Burchardt, T & Hick, R, 2018. Inequality, advantage and the capability approach. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 19(1), 38–52. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2017.1395396

- Cohen, S, 2013. States of denial: Knowing about atrocities and suffering. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

- Cuddy, AJC, Fiske, ST & Glick, P, 2008. Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS Map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 40, 61–149. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0.

- Dahl, RE, 2004. Adolescent brain development: A period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Keynote address. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1021(1), 1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001

- David, A, Guilbert, N, Hino, H, Leibbrandt, M, Potgieter, E & Shifa, M, 2018. Reconciliation & development working paper series. Number 3 Social cohesion and inequality in South Africa.

- Desmond, C, 1978. Christians or capitalists? Christianity and politics in South Africa. Bowerdean Press, London.

- Essex, MJ, Thomas Boyce, W, Hertzman, C, Lam, LL, Armstrong, JM, Neumann, SMA & Kobor, MS, 2013. Epigenetic vestiges of early developmental adversity: Childhood stress exposure and DNA methylation in adolescence. Child Development 84(1), 58–75. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01641.x.

- Fanon, F, 1965. The wretched of the earth. Grove Press, Inc, New York.

- Fodor, JA, 1983. Modularity of mind: An essay on faculty psychology. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Fodor, JA, 2000. The mind does not work that way: The scope and limits of computational psychology. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Freire, P, 1968. Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum, New York.

- Heckman, JJ, Stixrud, J & Urzua, S, 2006. The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. Journal of Labor Economics 24(3), 411–482. doi: 10.1086/504455

- Hindess, B, 2014. Choice, rationality and social theory (RLE social theory). Routledge, London. doi: 10.4324/9781315763729

- Honneth, A, 2004. Recognition and justice: Outline of a plural theory of justice. Acta Sociologica 47(4), 351–364. doi:10.1177/0001699304048668.

- Hundenborn, J, Leibbrandt, M & Woolard, I, 2018. Drivers of inequality in South Africa. WIDER Working Paper 2018/162. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Johnson, MH, 2001. Functional brain development in humans. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2(7), 475. doi: 10.1038/35081509

- Jost, JT, Banaji, MR & Nosek, BA, 2004. A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology 25(6), 881–919. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x.

- Klasen, S, Scholl, N, Lahoti, R, Ochmann, S & Vollmer, S, 2016. Inequality-worldwide trends and current debates. Courant Research Centre: Poverty, Equity and Growth-Discussion Papers. (No. 209).

- Leibbrandt, M, Ranchhod, V & Green, P, 2018. WIDER Working Paper 2018/184 Taking stock of South African income inequality. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Maboshe, M & Woolard, I, 2018. Revisiting the impact of direct taxes and transfers on poverty and inequality in South Africa. WIDER Working Paper 2018/79. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Mahali, A, 2017. ‘Without community, there is no liberation’: On #BlackGirlMagic and the rise of black woman-centred collectives in South Africa. Agenda (Durban, South Africa) 31(1), 28–41.

- Mani, A, Mullainathan, S, Shafir, E & Zhao, J, 2013. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 341(6149), 976–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1238041

- Marmot, M, 2005. Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet 365(9464), 1099–104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74234-3

- Maslow, AH, 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50(4), 370–96. doi:10.1037/h0054346.

- Max-Neef, MA, Hopenhayn, M & Hamrell, S, 1992. Human scale development: Conception, application and further reflections. Volume 1. The Apex Press, New York.

- Nussbaum, M, 2001. Women and human development: The capabilities approach. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Palmary, I, 2015. Reflections on social cohesion in contemporary South Africa. Psychology in Society 1(49), 62–9. doi: 10.17159/2309-8708/2015/n49a5

- Pinker, S, 1999. How the mind Works. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 882(1), 119–27. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08538.x.

- Posel, D & Casale, D, 2011. Relative standing and subjective well-being in South Africa: The role of perceptions, expectations and income mobility. Social Indicators Research 104(2), 195–223. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9740-2

- Prilleltensky, I & Gonick, L, 1996. Polities change, oppression remains: On the psychology and politics of oppression. Political Psychology 17(1), 127. doi:10.2307/3791946.

- Sameroff, A, 2010. A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development 81(1), 6–22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x.

- Sapolsky, R, 2017. Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. Penguin Press, New York & London.

- Sen, A, 1977. Rational fools: A critique of the behavioral foundations of economic theory. Philosophy and Public Affairs 6(4), 317–344.

- Sen, A, 1999. Development as freedom. 1st edn. Anchor Books, New York.

- Sen, A, 2003. Development as capability expansion. In Fukuda-Parr, AK & Kumar, S (Eds.), Readings in human development: Concepts, measures and policies for a development paradigm, 41–58. Oxford University Press, New Delhi & New York.

- Shonkoff, JP, Richter, LM, van der Gaag, J & Bhutta, ZA, 2012. An integrated scientific framework for child survival and early childhood development. Pediatrics 129(2), e460–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0366

- Starmans, C, Sheskin, M & Bloom, P, 2017. Why people prefer unequal societies. Nature Human Behaviour 1(4), 0082. doi:10.1038/s41562-017-0082.

- Van der Berg, S, 2011. Current poverty and income distribution in the context of South African history. Economic History of Developing Regions 26(1), 120–40. doi: 10.1080/20780389.2011.583018

- Walker, R, Bantebya Kyomuhendo, G, Chase, E, Choudhry, S, Gubrium, EK, Nicola, JY, Lødeme, I, Mathew, L, Mwiine, A, Pellisser, S & Ming, Y, 2013. Poverty in global perspective: Is shame a common denominator? Journal of Social Policy 42(2), 215–233. doi: 10.1017/S0047279412000979

- Wittenberg, M & Leibbrandt, M, 2017. Measuring inequality by asset indices: A general approach with application to South Africa. Review of Income and Wealth 63(4), 706–30. doi: 10.1111/roiw.12286

- Wolff, J & De-Shalit, A, 2007. Disadvantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.