ABSTRACT

For Africa to develop and achieve sustainable development, African governments have to prioritise spending on public health. However, the current spending data shows that health spending is a continuing struggle for African countries. Many researchers have the view that African governments have to collect more tax to spend enough on public healthcare. The question here is what extent people are willing to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare? Employing a multilevel regression model on Afrobarometer survey data, this paper examined to what extent individual and country level factors influence people’s willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare in 12 Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states. This study found that peoples’ trust in their government is an important determinant of willingness to pay more tax, while factors such as the country’s quality of democracy, economic condition, and current per capita health expenditure have no influence.

1. Introduction

The need for sound health and healthcare systems is an increasingly important objective for all countries in the world (WHO, Citation2013; Reich et al., Citation2016). In contemporary Africa, with one of the fastest growing populations in the world, population health is seen as one of the main prerequisites for Africa’s human, economic and political development (Uthman et al., Citation2015).

Understanding this, governments across Africa have started putting in practice population health at the forefront of their national policies (Gilson et al., Citation2003; Lagomarsino et al., Citation2012; WHO, Citation2013, Citation2016). In 2001, heads of the African Union (AU) member states met in Abuja, Nigeria and pledged to work together to eliminate the health crisis facing the African continent. The Abuja Declaration adopted by this meeting agreed to allocate ‘ … at least 15% of their annual budget to improve the health sector’ (WHO, Citation2011:1). However, this review by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2011 found that only two countries, Rwanda and South Africa, could achieve this target of allocating 15% of the annual budget to the health sector (WHO, Citation2011).

2. Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) and healthcare

The Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) is one of the largest Regional Economic Communities in the African Union (AU). Democracy in SADC countries has been strengthening since 1989 (Breytenbach, Citation2002; Muntschick, Citation2017) with almost all countries in the SADC region now being electoral democracies (van der Vleuten & Hulse, Citation2013; Muntschick, Citation2017), and for the state of democratisation in the SADC region, see Matlosa (Citation2017).

Access to healthcare remains one of the main challenges faced by countries in the SADC (Penfold, Citation2015; Ranchod et al., Citation2016). Under the SADC Regional Indicative Strategic Plan (RISDP), a key emphasis through the Social and Human Development and Special Programmes is the focus ‘ … on attaining an acceptable standard of health for all SADC citizens’.Footnote1 Furthermore, under the SADC Protocol on Health signed in August in 1999, which came into operation in 2004, great emphasis is placed on health within the community.

Under Article 19 of the SADC Protocol on Health, it is stipulated that state parties shall explore and share experience in relation to:

alternative and effective strategies for the mobilisation of sustainable funding for health services, particularly additional sources of revenue; and

optimal and efficient mechanisms for the allocation, utilisation and monitoring of health resources (SADC, Citation1999:7).

SADC’s resolve and commitment to looking after the health welfare of its people was further demonstrated by the signing of the Maseru Declaration at a meeting of all member states in Lesotho in 2003. The Maseru Declaration resolved, among other issues, to deal with health matters affecting the SADC region (SADC, Citation2003:2). Other policies have also been enacted aimed at responding to the health challenges within the SADC region. Included for example is the SADC regional HIV Prevention and Action Plan for universal access to prevention. This strategic policy was aimed at ‘strengthening of the monitoring and evaluation of regional multi sectoral response for HIV and AIDS … ’ (SADC, Citation2008:30).

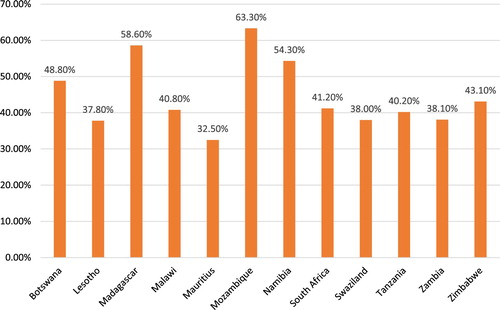

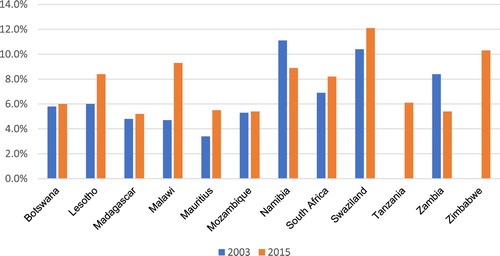

below shows the current health expenditure trend of all SADC member states from 2003 to 2015.

Figure 1. Health expenditure in SADC member states (% of general government expenditure) 2003 & 2005. Source: WHO global health expenditure database (http://apps.who.int/nha/database).

As signatory to the Abuja Declaration, meeting the goal of allocating 15% of national budgets to health is a continuing struggle for SADC member states. Evidence shows that African countries generally rely on external aid for spending on the social sector including health (Bräutigam & Knack, Citation2004; Moyo Citation2009; Juselius et al., Citation2014; Dieleman, Schneider, et al., Citation2016; Dieleman, Templin, et al., Citation2016). However, policy makers hold the view that reliance on aid is unsustainable and resource mobilisation through domestic tax collection is important for the unencumbered allocation of resources for social development (Gupta & Tareq, Citation2008; Drummond et al., Citation2012; Fakile et al., Citation2014). However, this view depends on the extent to which people are willing to pay more tax (e.g. see Gordon & Li, Citation2009).

Therefore, the question this research wants to answer is: what are the factors that determine people’s willingness to pay more taxes to increase spending on public healthcare in the SADC member states? Employing tax morale as a theoretical lens, a multilevel regression model is used to examine the effects of various factors on willingness to pay more taxes to increase spending on public healthcare at two levels: (1) individual socio-economic factors and people’s trust in their government; and (2) macro country level factors such as quality of democracy, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), life expectancy and current health expenditure (CHE).

3. Related literature: a brief review

There is consensus in the empirical literature that to understand why individuals may comply with paying taxes, it is important to explore their attitudes towards paying taxes (see e.g. Schnellenbach, Citation2006). The leading theoretical narrative underpinning this phenomenon is the concept of tax moral (Torgler, Citation2003a; Torgler, Citation2005). Tax morale, according to Torgler (Citation2005) is an intrinsic individual motivation to pay taxes. It is measured as a willingness to pay taxes out of the individual’s moral obligation (see e.g. Alm & Torgler, Citation2006; Keen et al., Citation2006; Torgler & Schneider, Citation2007) and the conviction that paying taxes contributes to society. For this study, the terms tax morale and willingness to pay tax are used interchangeably. In line with Alm & Torgler (Citation2006) and Torgler & Schneider (Citation2007), tax morale has a direct influence on a taxpayer’s behaviour. It has been suggested, however, that individual tax compliance behaviour is determined by different motivations. According to Luttmer & Singhal (Citation2014), there are five different mechanisms through which tax morale can influence individual tax compliance, namely: intrinsic motivations, peer effects and social influences, reciprocity, culture, information, and likelihood of being found guilty of tax evasion (see e.g. Keen et al., Citation2006). A brief summative analysis of the five mechanisms is given in the following section.

Intrinsic motivations – regarding intrinsic motivations, it is assumed that the motivation to comply with paying taxes is moulded by individual and institutional norms (Torgler, Citation2003a, Citation2003b). The broader argument here is that when individuals perceive state institutions (including tax authority/tax administration) as being fair (Cummings et al., Citation2004) and working in the interest of the nation, paying taxes is seen as a moral duty and beneficial to the nation. However, when state institutions including the tax institutions/system are perceived to be unfair, tax evasion could be deemed according to Cummings et al. (Citation2006) as the right appropriate practice for showing social disapproval.

Regarding peer effects and social influences, Luttmer & Singhal (Citation2014) argue that being tax compliant may also have an indirect effect on the tax behaviour of others. Frey & Torgler (Citation2007) contend that this is to a large extent because individuals are easily swayed by the actions of others, and thus, their willingness to pay tax may be likewise influenced by the compliance levels of others, or what is seen as socially acceptable behaviour (on this distinction see also Kasper, Citation2016). For instance, in a 2012 study on the effects of patriotism on tax compliance, Konrad & Qari (Citation2012) found that patriotic individuals exhibit higher levels of tax morale.

Regarding information and tax compliance, Luttmer and Singhal contend that the proper circulation of information about taxation can have an encouraging effect on peoples’ perceptions of tax. Recent empirical studies have propped up this assertion. For example, studies by Alm et al. (Citation2010), and Kasper et al. (Citation2015) found that increased tax knowledge through media campaigns can improve how individuals perceive tax systems, which can further influence tax compliance.

While Luttmer and Singhal’s five mechanisms provide a detailed analysis of the influences on tax compliance, other scholars have argued that tax compliance can also be influenced by factors such as the individual’s ethics. For instance, in a 2011 study about tax compliance and morality, Alm & Torgler (Citation2011) claim that there is considerable ‘direct and indirect evidence that ethics differ across individuals and that these differences matter in significant ways for their [individuals’] compliance decisions’ (635). While controlling for individual socio economic and country level factors, the present study examines the effects of trust in government on willingness to pay more taxes to increase spending on public healthcare in the SADC region in Africa.

4. Theoretical arguments

4.1. Trust in government & tax morale

The literature argues that trust in government is a key factor that influences tax morale (Torgler, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Badu & Chariye, Citation2015). According to Scholz & Lubell (Citation1998), trust in government and tax compliance are somewhat interconnected. Recent empirical studies have found that when individuals trust in institutions, including government, they inherently support the actions and to a large extent the policies which those institutions may put forth (Hays et al., Citation2005; Algan et al., Citation2011; Daniele & Geys, Citation2015). Torgler (Citation2003a) and Hammar et al. (Citation2009) assert that when people trust in government/institutions and the politics associated with those institutions, some kind of moral attachment is established which inherently creates a willingness to want to pay tax. This moral attachment to paying tax thus lessens the degree to which people may engage in tax evasion.

Therefore, trust in the institutions/government, according to Oh & Hong (Citation2012), makes people more willing to pay tax. Scholz & Pinney (Citation1995) argue that when people trust in institutions/government, an innate willingness to want to pay tax is inadvertently created. However, distrust in government may lead citizens to be hesitant about complying with government policies (e.g. see Lazarus, Citation1991), which can affect tax compliance and levels of support of other public projects. According to Zak & Knack (Citation2001) when this happens, it can have severe economic consequences for the country. Therefore, trust in government is imperative to increase support for government policies including health policies, taxation, and other public schemes.

A review of recent empirical studies highlights that individuals who trust their government are more likely to report tax morale (Torgler & Schneider, Citation2007). Evidence from both developed and developing democracies supports this claim. For example, in a 2006 study, Alm & Torgler used data from the World Value Survey (WVS) and compared tax morale between the United States of America and a number of European democracies. They looked for specific differences in tax morale between the USA and Spain and found that trust in government within those two countries had an irrefutable effect on tax morale. In a classic study on tax morale in the developing countries of South America, Torgler (Citation2005) used data from the Latinobarometro and WVS and found that individuals in Latin American developing countries who trusted their government were more likely to report tax morale than those that didn’t trust their government. Similarly, in an earlier study, Torgler (Citation2003b) used data from the WVS to examine tax morale in transition countries and found that tax morale is higher in Central and Eastern Europe than in the former Soviet Union countries. The study highlighted factors including trust in the government and in the legal system as having a positive effect on tax morale in transition economies.

In Africa, empirical studies have explored the relationship between trust in government and tax morale (see e.g. Badu & Chariye, Citation2015). Studies also have examined citizens’ attitudes towards taxation (Ali et al., Citation2014) and the determinants of tax compliance attitude in Africa (D’Arcy, Citation2009; Levi et al., Citation2009; Sacks, Citation2012). In a study on the effect of taxpayers’ attitudes towards the legal system and government on tax morale in Ethiopia, Badu & Chariye (Citation2015) found that trust in the legal system and government is positively correlated with tax morale . In their 2014 study, Ali et al. (Citation2014) examined citizens’ attitudes towards taxation in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and South Africa. Using the 2011/2012 Afrobarometer survey data, the study found that tax compliance attitude in the four countries is positively correlated with the provision of public service. In another study about tax compliance, Cummings et al. (Citation2009) used survey data as well as field experiments to examine whether cross-cultural differences can explain tax compliance behaviour in Botswana and South Africa. The study found that compared to South Africa, individuals in Botswana are more tax compliant, largely because they view their government as being fairer and more efficient. There is also a consensus in much of the literature that trust in government is a multidimensional concept that is influenced by several factors. These factors include, for example, having ties to a government such as being an employee of that government. According to Brewer & Sigelman (Citation2002), having direct ties to government may influence the individual’s positive perception about that government. Political party affiliation is one of the other factors which has been found to influence peoples’ trust in government. According to Gershtenson et al. (Citation2006), individuals may trust a government if a political party with which they identify is in power and controls the government.

Several other factors have also been found to influence individuals’ trust in their government. For example, in a 2006 study, Hudson (Citation2006) used the Eurobarometer data on both well-being and institutional trust to examine the extent to which trust or distrust in institutions impacts well-being. The study found that in the European Union (EU), trust in governmental institutions increases with employment status, education and household income, and varies with age. In the Dominican Republic in Central America, Espinal et al. (Citation2006) found that individuals in receipt of a middle income had significantly less trust in their government institutions than either the poor or the wealthy class.

In the context of North America, Avery (Citation2006) found that race consciousness is one of the main factors that influences peoples’ trust in government and its institutions, especially for African Americans. This study used data from the National Black Election Studies (NBES) for 1984 and 1996 and found that lack of political trust among African Americans is distinct from other races, including the white race, and is to a greater extent associated with displeasure with the political system. Using data collected before and after the 2002 congressional elections, Gershtenson et al. (Citation2006) found that support of a government and its institutions is directly correlated with the political party one identifies with (i.e. Democrat or Republican in the USA) as well as which party controls government at a given time. Their study found evidence implying that ‘ … party control of government and party identification are important in explaining trust and institutional approval’ in the USA (Citation2006:889).

4.2. Democracy & tax morale

In addition to the literature that supports the statement that trust in government impacts tax morale, there is also a consensus in the majority of the literature, that supports how democracy influence tax morale (e.g. Feld & Frey, Citation2002; Torgler, Citation2005; Torgler & Schneider, Citation2007). The key argument in this literature is that individuals who support democracy as a preferred form of government exhibit higher tax morale than those who do not (Torgler, Citation2005; Torgler & Schneider, Citation2007).Footnote2

There is empirical evidence from different parts of the world of the notion that support for democracy as a system of governance affects tax morale. In Europe, for instance, in a 2007 comparative study about what affects attitudes towards paying taxes in three multicultural countries in the European Union, viz. Belgium, Spain, and Switzerland, Torgler & Schneider (Citation2007) found that in Belgium and Spain, individuals who support democracy as a form of government exhibited higher levels of tax morale . Furthermore, in a 2010 study on the determinates of tax morale in the European countries, Lago-Peñas & Lago-Peñas (Citation2010) found that individuals’ political attitudes, including satisfaction with democracy, is positively related to tax morale.

In South America, it has been found that supporting democracy or having pro-democratic views affects tax morale. For example, in a study on tax morale in Latin America, Torgler (Citation2005) found that individuals who held ‘pro-democratic attitudes have a highly significant positive effect on tax morale’ (Torgler, Citation2005:151). Similarly, in an earlier study on tax morale in several Asian countries, Torgler (Citation2004) also found a positive correlation between pro-democracy attitude and tax morale. In Africa, recent empirical studies have found that individuals who trust the legal systems and support democracy as a system of governance were more likely than those who do not to exhibit high tax morale (Levi et al., Citation2009; Daude et al., Citation2013; Ibrahim et al., Citation2015).

4.3. Quality of democracy and tax morale

As the studies have found that people who support the democratic form of government exhibit higher levels of tax morale, it is interesting to see how the quality of democracyFootnote3 in the countries in which they live influences their decision to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare. Although there is limited empirical research in this area, some available studies have found that the country’s quality of democracy has no influence on certain aspects of taxation. For example, using a cross-section dataset of 75 developed and developing countries, Adam et al. (Citation2015) examined the effect of income inequality on tax policy, and ‘ … the results show that income inequality affects capital tax rates positively and labour tax rates negatively. This result is unaffected by the quality of democracy or by the regime of the countries’ (cited in Balamatsias, Citation2017:12). Other studies have found a positive correlation between institutional quality and tax morale if state institutions are perceived to be trustworthy (e.g. see Frey & Torgler (Citation2007)). By contrast, other studies have found that the strength of a country’s democratic institutions has no correlation with attitudes towards tax. For example, in a 2013 study which focused on developing countries in three geographical regions of the world, viz. South-East Asia, Latin America, and the European Union, Profeta et al. (Citation2013) investigated the relation between political variables (measured by POLITY2 index included in the Polity IV dataset, and the civil liberties indicator in the Freedom House dataset) and tax revenue, public spending and their structure. Their study found that ‘tax revenue and tax composition are in general not significantly correlated with the strength of democratic institutions … ’ (Citation2013:1). Using data from the European Social Survey, Svallfors (Citation2013) examined how perceptions of government quality – in terms of impartiality and efficiency – impact on attitudes to taxes and social spending. The study found that perceptions of the quality of government have no effect on attitudes to taxes and spending.

For the present study, the study uses the democracy index for the year 2015, an indicator of quality of democracy,Footnote4 calculated by the Economist Intelligence Unit (https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index) to explore its influence on peoples’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare in 12 SADC member states.

4.4. Demographics and willingness to pay tax

Tax morale, the literature argues, is a complex concept as it can be influenced by several socio-demographic factors including age, gender, income, education level, and employment status. For instance, in Lago-Peñas & Lago-Peñas (Citation2010) study on the determinates of tax morale within the European countries, tax morale was found to be ‘positively related to age, being male, income (the higher the financial stress, the stronger the tax morale), satisfaction with democracy, trust in politicians and agreement with redistribution’ (Lago-Peñas & Lago-Peñas (Citation2010:22)).

In Asia, a 2016 study on the determinates of tax morale in Pakistan found that more highly educated people exhibited higher tax morale than illiterate people. From a gender perspective, the study also found that, compared to males, females exhibited higher tax morale. However, when age was taken into consideration, it was found that compared to older males, older females have lower (Cyan et al., Citation2016). This finding supports other empirical studies showing similar results. For example, in a study on culture differences and tax moral in the United States and Europe, Alm & Torgler (Citation2006) found that females have higher tax morale than males. In Latin America, studies indicate that socio-demographic characteristics such as older age are directly related to tax morale (Torgler, Citation2005). Similar studies in Africa and from other parts of the world show that socio-economic dynamics such as age, employment status, gender, and educational attainment influence individuals’ levels of tax morale (see e.g. studies including Levi et al., Citation2009; Daude et al., Citation2012).

Tax morale has been found to play a meaningful role in tax compliance behaviour, at least within the context of developed countries, on which much of the evidence appears to be largely based (on this distinction, see Luttmer & Singhal, Citation2014). To date, no study in Africa and in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region in particular, has specifically looked into the relationship between trust in government, the country’s quality of democracy, and the individual’s willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare.

Set against this theoretical backdrop and empirical gap, this research set out to examine the extent to which trust in government and quality of democracy influences individuals’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare in 12 SADC member states.

5. Data and methods

5.1. Data source

To examine the relationship between trust in government and individuals’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare, the study used data from Round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey collected during the 2013–2014 period.Footnote5 The Afrobarometer survey is an independent non-partisan research project that measures the social, political, and economic atmosphere in Africa (www.afrobarometer.org). The data used covers 12 countries in the SADC namely: Botswana, Malawi, Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius, Namibia, Lesotho, Swaziland,Footnote6 South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The SADC is made up of 16 countries, but Angola, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the Seychelles were not covered during Round 6 of the Afrobarometer Surveys. The sample size for each country was 1200 respondents although Zambia had 1999 respondents.Footnote7 The SADC region was chosen for this study because it is one of the largest economic blocs in the whole of Africa. This region of Africa is also one of the most affected by deadly diseases such HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, and thus provides a ripe contextual backdrop to measuring peoples’ opinions in relation to this study’s question.

5.2. Dependent variable

The Afrobarometer Round 6 survey questioned respondents as to whether or not they were willing to pay more tax in order to increase spending on public healthcare.Footnote8 This information is taken as the dependent variable and an indicator to measure the respondents’ willingness to pay more tax in order to increase spending on public healthcare. There were seven options given for responding to that question and for the analysis, the options were dichotomised into Yes = willing to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare and Else = other answers. shows details of the participants’ responses.

5.3. Independent variables

The independent variable ‘trust in government’ is operationalised as follows:

In the Afrobarometer Round 6 survey, respondents were asked how much they trust – The President, Parliament, ‘Revenue Authority’, local government, and the Ruling Party. The answer options range from 0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘a lot’. An additive index ‘Trust in government’ was created by adding the scores of the above five variables, thus having each variable with the same weight.

To control for individual socio-economic variation, the following control variables were included in the model:

5.4. Individual socio-economic characteristics

Age is categorised into three categories; young age (up to 24 years), middle age (25–39 years) and old age (40 and over).

Gender is a binary variable taking the value 1 if the respondent is male and zero if not.

Educational attainment was recoded into three categories viz. Low education, Middle education, High education. The ‘Low education’ category included those who reported had ‘No formal schooling’, ‘Informal schooling only’, ‘Some primary schooling’, or ‘Primary school completed’. The ‘Middle education’ category included those having ‘some secondary school/high school’, ‘Secondary school completed/high school’, or ‘Post-secondary qualifications, not university’. The ‘High education’ category comprises respondents having ‘Some university’, ‘University completed’, or ‘Post-graduate’.

Residence was split into urban or rural.

Employment status is a dummy variable which equates to 1 = employed, 0 = unemployed.

How often a respondent has gone without medical cover is coded as 0 = went without care/once or twice and 1 = went without care several times/ many times/always.

Access to medical care relates to responses to the question: How easy or difficult was it to obtain the medical care you needed? With answer options ranging from very easy to very difficult, a dummy variable was created, by which 0 = ‘very easy/easy’ and 1 = ‘difficult/very difficult’.

5.5. Country level characteristics

To control for country level variation in socio-economic factors, the following variables were included in the regression model:

Life expectancy in the year 2015 as estimated by the World Bank.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita for the year 2015 as estimated by the World Bank (Purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP current international $).Footnote9

Democracy index for the year 2015 as calculated by the Economist Intelligence Unit.Footnote10

Current Health Expenditure (CHE) per capita for the year 2015 as estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) ().

Table 1. Country level variables included in the regression model.

6. Results and discussion

below presents the results of the multilevel logistic regression model, estimating the effect of individual socio-economic factors and country level factors on individuals’ willingness to pay more tax in order to increase spending on public healthcare in 12 SADC member states.

Table 2. Multilevel regression results: individual level and country level factors determining willingness to pay more tax.

The central aim of this study was to explore the influence of peoples’ trust in their government on their willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare in 12 Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states. The analysis found that as peoples’ trust in government increases, their willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare also increases (odds ratio = 1.052). This analysis found that several individual socio-economic factors also significantly influence peoples’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare. For example, compared to the older age group, people in the younger age group are shown to be more willing to pay extra (odds ratio = 1.142). Education is also found to be a factor that significantly influences willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare. Compared to people with a low level of education, middle educated (odds ratio = 1.143) and highly educated people (odds ratio = 1.295) are shown to be more willing to pay more tax for public healthcare spending. Compared to people residing in urban areas, those residing in rural areas (odds ratio = 1.118) are shown to be more willing to pay more tax to increase public healthcare spending. The analysis shows that gender and employment status have no influence on peoples’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare in the 12 SADC member states.

This study also examined to what extent availability and access to medical care can influence peoples’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare. The results show that, compared to those who indicated that they have difficulty in accessing medical care, those who reported having easy access (odds ratio = 1.162) are found to be more willing to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare. At the same time, availability of medical care, measured in terms of how often individuals have gone without medical care, is found not to significantly influence peoples’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare. Interestingly, people who had difficulty in accessing medical care or had gone without medical care were found less willing to pay more tax to fund public healthcare. This might be because in the peculiar African context, people who are not familiar with functioning public health systems may not know the benefits.

The multilevel logistic regression model shows that several country level factors have no significant influence on individuals’ decisions as to their willingness to pay more tax for this purpose. The present analysis found that irrespective of the quality of the democratic system under which people live (measured using the Democracy Index), current national spending on health measured as Current Health Expenditure (CHE), current national financial status measured as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and people’s general health status measured as Life Expectancy have no significant influence on individuals’ willingness to pay more tax to increase public healthcare spending in the 12 SADC countries under study.

Studies elsewhere have also shown a positive relationship between trust in government and tax morale (e.g. Torgler, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Badu & Chariye, Citation2015). The present analysis supports the argument that individuals’ trust in government is one of the main factors that determines people’s willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare in the 12 SADC member states. This analysis also found that individuals who reported having easy access to healthcare exhibited higher tax morale than those with less access to healthcare services. These findings emphasise the current understanding that people are more willing to pay for healthcare if they have easy access to it. This is in line with the findings by Daude et al. (Citation2012), who found a positive correlation between tax morale and satisfaction with healthcare in Africa. One interesting finding is that the country’s quality of democracy has no statistically significant influence on individuals’ willingness to pay more tax to increase spending on healthcare. A probable explanation for this is the individuals’ desire to have sound healthcare far outweighs their views on the quality of democracy under which they live.

7. Conclusions

In contemporary Africa, interest is growing from both academics and policy makers in the fields of health, healthcare, and policy regarding the effect of government programmes to promote sustainable healthcare through local taxation. Researchers argue that increasing local taxation is one effective and potential way to help fund health programmes in Africa (e.g. Gupta & Tareq, Citation2008; Ali et al., Citation2014; Fakile et al., Citation2014). The intention of this research is to explore some of the theoretical facets and information gaps that are essential in understanding the influence of micro and macro level factors including trust in government and quality of democracy on people’s decision to pay more tax to increase spending on public healthcare in 12 Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) member states. The study highlighted the recent empirical findings which show the unlikelihood of many of the African countries, including the majority of the SADC region, achieving the 15% annual budget allocation threshold.

The question posed in the research is: are people in the SADC member states willing to pay more tax in order to increase spending on public healthcare? In answering the research question, it was found that in the 12 SADC member states selected for this study, individuals’ trust in their government is positively correlated with willingness to pay more tax in order to increase spending on public healthcare. However, the quality of democracy in individual SADC member states, Current Health Expenditure (CHE), life expectancy, and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) were found to have no influence on willingness to pay tax for this purpose.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 For an analysis of the main focus of the Social and Human Development and Special Programmes, visit: http://www.sadc.int/sadc-secretariat/directorates/office-deputy-executive-secretary-regional-integration/socialhuman-development-special-programmes/.

2 These studies measured support for democracy from questions in the world value survey (see e.g. Torgler, Citation2005).

3 Quality of democracy calculated by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy, on a 0 to 10 scale, is based on the ratings for 60 indicators, grouped into five categories: electoral process and pluralism; civil liberties; the functioning of government; political participation; and political culture. Each category has a rating one 0 to 10 scale, and the overall Index is the simple average of the five category indexes(https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index).

4 The Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy, on a 0 to 10 scale, is based on the ratings for 60 indicators, grouped into five categories: electoral process and pluralism; civil liberties; the functioning of government; political participation; and political culture. Each category has a rating one 0 to 10 scale, and the overall Index is the simple average of the five category indexes.

5 This round has all the data available for this analysis.

6 Please note that Swaziland changed its name to Eswatini on 9 April 2018.

7 The difference in sample size has no major influence on the conclusions.

8 It is important to note that this was a closed ended question. The respondents were not presented with other options such as; (a) if other taxes were reduced (i.e. a balanced budget approach) - which would mean a reprioritisation of government spending; (b) if a new tax is introduced without reducing any other taxes (i.e. the total tax burden is increased) and that is progressive or regressive or neutral with reference to taxable income, and; (c) if the additional tax revenue were to be earmarked (given that it would be possible), etc.

9 Gross Domestic Product is included in the regression model taking into consideration income variation.

10 The Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy, on a 0 to 10 scale, is based on the ratings for 60 indicators, grouped into five categories: electoral process and pluralism; civil liberties; the functioning of government; political participation; and political culture. Each category has a rating on a 0 to 10 scale, and the overall Index is the simple average of the five category indexes: https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index.

References

- Adam, A, Kammas, P & Lapatinas, A, 2015. Income inequality and the tax structure: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Journal of Comparative Economics 43(1), 138–54.

- Algan, Y, Cahuc, P & Sangnier, M, 2011. Efficient and inefficient welfare states. IZA: Institute of Labor Economics, Discussion Paper No. 5445.

- Ali, M, Fjeldstad, OH & Sjursen, IH, 2014. To pay or not to pay? Citizens' attitudes toward taxation in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and South Africa. World Development 64, 828–842.

- Alm, J & Torgler, B, 2006. Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology 27(2), 224–46.

- Alm, J & Torgler, B, 2011. Do ethics matter? Tax compliance and morality. Journal of Business Ethics 101(4), 635–51.

- Alm, J, Cherry, T, Jones, M & McKee, M, 2010. Taxpayer information assistance services and tax compliance behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology 31(4), 577–86.

- Avery, JM, 2006. The sources and consequences of political mistrust among African Americans. American Politics Research 34(5), 653–82.

- Badu, N & Chariye, A, 2015. The effect of taxpayers’ attitudes towards the legal system and government on tax morale. European Journal of Business and Management 7(1), 321.

- Balamatsias, P, 2017. Democracy and taxation. Economics Discussion Papers, No. 2017–100, Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW), Kiel.

- Bräutigam, DA & Knack, S, 2004. Foreign aid, institutions, and governance in Sub-saharan Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change 52(2), 255–85.

- Brewer, PR & Sigelman, L, 2002. Trust in government: Personal ties that bind? Social Science Quarterly 83(2), 624–31.

- Breytenbach, W, 2002. Democracy in the SADC region: A comparative overview. African Security Review 11(4), 87–102.

- Cummings, RG, Martinez-Vazquez, J, McKee, M & Torgler, B, 2004. Effects of culture on tax compliance: A cross check of experimental and survey evidence. CREMA Working Paper No. 2004-13.

- Cummings, RG, Martinez-Vazquez, J, McKee, M & Torgler, B, 2006. Effects of tax morale on tax compliance: Experimental and survey evidence. Berkeley Program in Law and Economics, UC Berkeley.

- Cummings, RG, Martinez-Vazquez, J, McKee, M & Torgler, B, 2009. Tax morale affects tax compliance: Evidence from surveys and an artefactual field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 70(3), 447–57.

- Cyan, MR, Koumpias, AM & Martinez-Vazquez, J, 2016. The determinants of tax morale in Pakistan. Journal of Asian Economics 47, 23–34.

- Daniele, G & Geys, B, 2015. Public support for European fiscal integration in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy 22(5), 650–70.

- D’Arcy, M, 2009. Why do citizens assent to pay tax? Legitimacy, taxation and the african state? Afrobarometer working paper, No. 126.

- Daude, C, Gutiérrez, H & Melguizo, Á, 2012. What drives tax morale? OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 315, OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/what-drives-tax-morale_5k8zk8m61kzq-en.

- Daude, C, Gutierrez, H & Melguizo, A, 2013. What drives tax morale? A focus on emerging economies. Review of Public Economics 207(4), 9–40.

- Dieleman, JL, Schneider, MT, Haakenstad, A, Singh, L, Sadat, N, Birger, M, Reynolds, A, Templin, T, Hamavid, H & Chapin, A, 2016. Development assistance for health: Past trends, associations, and the future of international financial flows for health. The Lancet 387(10037), 2536–44.

- Dieleman, JL, Templin, T, Sadat, N, Reidy, P, Chapin, A, Foreman, K, Haakenstad, A, Evans, T, Murray, CJ & Kurowski, C, 2016. National spending on health by source for 184 countries between 2013 and 2040. The Lancet 387(10037), 2521–35.

- Drummond, P, Daal, W, Srivastava, N & Oliveira, L, 2012. Mobilizing revenue in Sub-Saharan Africa: Empirical norms and key determinants. IMF Working Paper WP/12/108.

- Espinal, R, Hartlyn, J & Kelly, JM, 2006. Performance still matters: Explaining trust in government in the Dominican Republic. Comparative Political Studies 39(2), 200–23.

- Fakile, AS, Adegbie, FF & Samuel, O, 2014. Mobilizing domestic revenue for sustainable development in Africa. European Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance Research 2(2), 91–108.

- Feld, LP & Frey, BS, 2002. Trust breeds trust: How taxpayers are treated. Economics of Governance 3(2), 87–99.

- Frey, BS & Torgler, B, 2007. Tax morale and conditional cooperation. Journal of Comparative Economics 35(1), 136–59.

- Gershtenson, J, Ladewig, J & Plane, DL, 2006. Parties, institutional control, and trust in government. Social Science Quarterly 87(4), 882–902.

- Gilson, L, Doherty, J, Lake, S, McIntyre, D, Mwikisa, C & Thomas, S, 2003. The saza study: Implementing health financing reform in South Africa and Zambia. Health Policy and Planning 18(1), 31–46.

- Gordon, R & Li, W, 2009. Tax structures in developing countries: Many puzzles and a possible explanation. Journal of Public Economics 93(7–8), 855–66.

- Gupta, S & Tareq, S, 2008. Mobilizing revenue. Finance and Development 45(3), 44–47.

- Hammar, H, Jagers, SC & Nordblom, K, 2009. Perceived tax evasion and the importance of trust. The Journal of Socio-Economics 38, 238–245.

- Hays, JC, Ehrlich, SD & Peinhardt, C, 2005. Government spending and public support for trade in the oecd: An empirical test of the embedded liberalism thesis. International Organization 59(2), 473–94.

- Hudson, J, 2006. Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the eu. Kyklos 59(1), 43–62.

- Ibrahim, M, Musah, A & Abdul-Hanan, A, 2015. Beyond enforcement: What drives tax morale in Ghana? Humanomics 31(4), 399–414.

- Juselius, K, Møller, NF & Tarp, F, 2014. The long-run impact of foreign aid in 36 African countries: Insights from multivariate time series analysis. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 76(2), 153–84.

- Kasper, M, 2016. How do institutional, social, and individual factors shape tax compliance behavior? Evidence from 14 eastern European countries. WU International Taxation Research Paper Series No. 2016 - 04.

- Kasper, M, Kogler, C & Kirchler, E, 2015. Tax policy and the news: An empirical analysis of taxpayers’ perceptions of tax-related media coverage and its impact on tax compliance. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 54, 58–63.

- Keen, M, Kim, Y & Varsano, R, 2006. The “flat tax(es)”: Principles and evidence. IMF Working Paper/06/218.

- Konrad, KA & Qari, S, 2012. The last refuge of a scoundrel? Patriotism and tax compliance. Economica 79(315), 516–33.

- Lagomarsino, G, Garabrant, A, Adyas, A, Muga, R & Otoo, N, 2012. Moving towards universal health coverage: Health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. The Lancet 380(9845), 933–43.

- Lago-Peñas, I & Lago-Peñas, S, 2010. The determinants of tax morale in comparative perspective: Evidence from European countries. European Journal of Political Economy 26(4), 441–53.

- Lazarus, RJ, 1991. The tragedy of distrust in the implementation of federal environmental law. Law and Contemporary Problems 54(4), 311–74.

- Levi, M, Sacks, A & Tyler, T, 2009. Conceptualizing legitimacy, measuring legitimating beliefs. American Behavioral Scientist 53(3), 354–75.

- Luttmer, EF & Singhal, M, 2014. Tax morale. Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(4), 149–68.

- Matlosa, K, 2017. The state of democratisation in Southern Africa: Blocked transitions, reversals, stagnation, progress and prospects. Politikon 44(1), 5–26.

- Moyo, D, 2009. Why foreign aid is hurting Africa. The Wall Street Journal 21, 1–2. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB123758895999200083 Accessed 28 June 2018.

- Muntschick, J, 2017. The impact of regionalism on democracy building: An examination of the Southern African development community (SADC). In Ngwainmbi, Emmanuel, K (Eds), Citizenship, democracies, and media engagement among emerging economies and marginalized communities, 55–80. Cham, Palgrave.

- Oh, H & Hong, JH, 2012. Citizens’ trust in government and their willingness-to-pay. Economics Letters 115(3), 345–47.

- Penfold, E, 2015. Southern African development community health policy: Under construction PRARI Policy Brief: The Open University. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/southern-african-development-community-health-policy-under-construction/ Accessed 11 January 2018.

- Profeta, P, Puglisi, R & Scabrosetti, S, 2013. Does democracy affect taxation and government spending? Evidence from developing countries. Journal of Comparative Economics 41(3), 684–718.

- Ranchod, S, Erasmus, D, Abraham, M, Bloch, J, Chigiji, K & Dreyer, K, 2016. Effective health financing models in SADC: Three case studies. FinMark Trust. https://finmark.org.za/health-financing-models-in-sadc-three-case-studies/ Accessed 26 September 2018.

- Reich, MR, Harris, J, Ikegami, N, Maeda, A, Cashin, C, Araujo, EC, Takemi, K & Evans, TG, 2016. Moving towards universal health coverage: Lessons from 11 country studies. The Lancet 387(10020), 811–16.

- Sacks, A, 2012. Can donors and non-state actors undermine citizens’ legitimating beliefs? Policy Research working paper; No. WPS 6158, World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11997 Accessed 19 March 2018.

- SADC, 1999. Protocol on health. Southern African Development Community. http://www.ifrc.org/docs/IDRL/Southern%20African%20Development%20Community.pdf Accessed 27 November 2017.

- SADC, 2003. Maseru declaration on the fight against HIV/AIDS in the SADC region. Southern African Development Community. https://www.sadc.int/files/6613/5333/0731/Maseru_Declaration_on_the_fight_against_HIVand_AIDS2003.pdf.pdf Accessed 27 November 2017.

- SADC, 2008. Activity report of the SADC secretariat: For the period August 2007 to July 2008. Southern African Development Community. https://www.sadc.int/files/3813/5333/8237/SADC_Annual_Report_2007_-_2008.pdf Accessed 19 November 2017.

- Schnellenbach, J, 2006. Tax morale and the taming of leviathan. Constitutional Political Economy 17(2), 117–32.

- Scholz, JT & Lubell, M, 1998. Trust and taxpaying: Testing the heuristic approach to collective action. American Journal of Political Science 42(2), 398–417.

- Scholz, JT & Pinney, N, 1995. Duty, fear, and tax compliance: The heuristic basis of citizenship behavior. American Journal of Political Science 39(2), 490–512.

- Svallfors, S, 2013. Government quality, egalitarianism, and attitudes to taxes and social spending: A European comparison. European Political Science Review 5(3), 363–80.

- Torgler, B, 2003a. Tax morale and institutions. Center for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts (CREMA): CREMA Working Paper Series 2003-09.

- Torgler, B, 2003b. Tax morale, rule-governed behaviour and trust. Constitutional Political Economy 14(2), 119–40.

- Torgler, B, 2004. Tax morale in Asian countries. Journal of Asian Economics 15(2), 237–66.

- Torgler, B, 2005. Tax morale in Latin America. Public Choice 122(1–2), 133–57.

- Torgler, B & Schneider, F, 2007. What shapes attitudes toward paying taxes? Evidence from multicultural European countries. Social Science Quarterly 88(2), 443–70.

- Uthman, OA, Wiysonge, CS, Ota, MO, Nicol, M, Hussey, GD, Ndumbe, PM & Mayosi, BM, 2015. Increasing the value of health research in the WHO African region beyond 2015—reflecting on the past, celebrating the present and building the future: A bibliometric analysis. BMJ Open 5(3), e006340.

- van der Vleuten, A & Hulse, M, 2013. Governance transfer by the southern African development community (SADC). SFB-Governance Working Paper Series 48.

- WHO, 2011. The Abuja declaration: Ten years on. World Health Organization, Geneva. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/abuja_report_aug_2011.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 19 November 2017.

- WHO, 2016. Public financing for health in Africa: from Abuja to the SDGs (No. WHO/HIS/HGF/Tech. Report/16.2).

- WHO, 2013. State of health financing in the African region: WHO Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/state-of-health-financing-afro.pdf Accessed 12 June 2018

- Zak, PJ & Knack, S, 2001. Trust and growth. The Economic Journal 111(470), 295–321.