ABSTRACT

South Africa has potential to export honey products through promoting beekeeping as an income generating opportunity amongst rural communities. Formalised beekeeping may also reduce wild fires initiated by hunters of wild bee hives. This study examined the contribution of the African Honey Bee (AHB) initiative to rural livelihoods and the incidence of forest fires using a mixed methods approach. The initiative increased incomes of newly trained and active beekeepers, although success rates and honey yields were variable. Core challenges included not catching bees, theft and vandalism of hives, insufficient bee forage, drought and pests. Most respondents also perceived an increase in crop size since AHB began, although few attributed this to pollination from the bees. The number of wild fires attributed to honey hunters more than halved after AHB began. Future steps need to reduce the challenges and integrate beekeeping into broader agriculture and forest conservation programmes.

1. Introduction

Beekeeping produces a variety of different products such as honey, beeswax, royal jelly, and propolis, which can provide a steady source of income (Bradbear Citation2004; Tesfaye et al. Citation2017). It also provides numerous indirect benefits, such as pollination and maintenance of genetic diversity of many plant and crop species, and their cultural value in communities (Bradbear Citation2004). Due to the many benefits it provides, beekeeping is potentially a valuable contribution to rural livelihoods whilst simultaneously benefiting the environment (Bradbear Citation2004; Peter Citation2015; Yusuf et al. Citation2018). Beekeeping is prevalent in many countries throughout sub-Saharan Africa including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe (Fabricius et al. Citation2004; Amulen et al. Citation2017; Yusuf et al. Citation2018). Despite the potential, Africa’s contribution to world honey trade remains low as a result of market chain inefficiencies and land transformation (Amulen et al. Citation2017; Yusuf et al. Citation2018). However, Africa potentially holds a comparative advantage in the organic and fair-trade sectors because the majority of honey is produced organically at household scale and isn’t artificially processed (Amulen et al. Citation2017). For example, Girma & Gardebroek (Citation2015) reported higher incomes to honey producers under organic certification in southwestern Ethiopia and Paumgarten et al. (Citation2012) discuss the benefits accruing through membership of certified producer organisations in Zambia. However, the potential advantage of organic certification schemes can be undermined by weak monitoring and compliance with certification regulations, as revealed by Musinguzi et al. (Citation2018) in eastern Kenya and Paumgarten et al. (Citation2012) in Zambia.

Although estimates are variable (Conradie & Nortjé Citation2008) it appears that the beekeeping industry in South Africa is comparatively small in relation to global and African honey production (SABIO Citation2008). The honey industry is dominated by commercial beekeepers which contribute 80% of the approximately 1700–2000 tons produced every year (SABIO Citation2008; Peter Citation2015). The current demand is approximately 2700–3000 tons per year, resulting in a shortage of approximately 1000 tons which is imported (SABIO Citation2008). Yet there is significant unexploited bee forage, indicating that South Africa has potential to produce surplus honey (Peter Citation2015; Yusuf et al. Citation2018). Commercial beekeepers are unable to singly support and sustain the honeybee population in the country due to a lack of funding and infrastructure. Therefore, there is room for new beekeepers to enter which is also vital for the success of the South African beekeeping industry (SABIO Citation2008). The South African government and the South African Bee Industry Organisation (SABIO) have been increasingly involved in establishing projects to encourage the involvement of rural communities in beekeeping (SABIO Citation2008). However, most have not met expectations due to a lack of on-going financial or technical support, marketing inefficiencies, diseases and theft and vandalism (SABIO Citation2008; Peter Citation2015; Yusuf et al. Citation2018). For example, Yusuf et al.’s (Citation2018) evaluation of eight projects in the Eastern Cape province found that almost 40% of the hives had not been colonised by bees, largely due to the poor maintenance of the hives. Additionally, the local agricultural officers lacked technical skills in beekeeping, and the producers lacked marketing skills for their products. Theft of honey and hives, or vandalism of hives was also a demotivating factor in all eight projects (Yusuf et al. Citation2018), and a concern nationally (Conradie & Nortjé Citation2008).

According to Bradbear (Citation2004), beekeeping can contribute to rural livelihoods with very little investment. It does not require extensive land, and can be set up with equipment that can be sourced from local natural resources, such as hollow logs (Hilmi et al. Citation2011). It does not require significant knowledge or skills, and appropriate knowledge often already exists in many rural communities (Hilmi et al. Citation2011). Although beekeeping in sub-Saharan Africa can provide additional income to rural communities, it is rarely the sole source of livelihood, except for specialist beekeepers (Conradie & Nortjé Citation2008; Peter Citation2015; Kasumbu & Pullanikkatil Citation2019). It contributes to diversification and can be implemented in rural areas where the land is unsuitable for farming or where arable land is limited (Peter Citation2015). Due to the low labour intensity of beekeeping it can be practiced by all ages and genders (Mujuni et al. Citation2012).

The benefits of beekeeping are not limited to the direct incomes and skills development, but that it supports other livelihood sectors, most notably agriculture. Agriculture makes meaningful contributions to household and national economies in many sub-Saharan countries, including South Africa (Goldblatt Citation2015). The agricultural sector contributes to the gross domestic product of a country, whilst also underpinning food security, social welfare, job provision and a sense of identity (Goldblatt Citation2015). Beekeeping harmonises with agriculture because of the pollination services provided by the bees, which can result in increased crop yields and sizes (Pywell et al. Citation2015). On an international scale, honey bees are responsible for approximately 90% of commercial pollination services and the need for agricultural pollination is on the rise (Allsopp et al. Citation2008).

Beekeeping can also contribute to pollination services of non-crop species. Many wild plant species are collected and used by rural households throughout sub-Saharan Africa, for fruits, wild foods, medicines, crafts and culture (Shackleton & Shackleton Citation2004; Angelsen et al. Citation2014), and the continued productivity and population stability of many is dependent on pollinators, including bees. The productivity of the wild plants also supports other species and ecological trophic webs (Senapathi et al. Citation2015). Maintaining species diversity and productivity is fundamental to promoting ecosystem resilience (Senapathi et al. Citation2015). In this way, bees are intricately linked to the health of forests and other ecosystems (Fabricius et al. Citation2004). However, traditional methods of obtaining honey, such as honey hunting, can sometimes have negative effects on forests and the environment. This is because honey ‘robbers’ may fell trees to access cavities with bee hives (Ribeiro et al. Citation2019) or pacify bees with smoke from smouldering dung or leaves (Fabricius et al. Citation2004; Bradbear Citation2009; Meddour-Sahar et al. Citation2013). At times the smouldering material is discarded, resulting in wild fires (Meddour-Sahar et al. Citation2013), which can be damaging to the conservation and productivity of local vegetation and habitats (Park & Youn Citation2012). Thus, promotion and adoption of beekeeping may reduce wild fire frequencies in indigenous forests. Yet there is no assessment of such.

Within this context the African Honeybee Initiative (AHB) has been promoting beekeeping in rural communities throughout South Africa, especially in the more forested areas where there is plentiful forage for bees, but also a high risk of wild fires. The programme seeks to support rural households to develop micro-businesses which produce raw honey in an environmentally and ethical manner (Stubbs Citation2018). During the last two years AHB has trained 1200 people in Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo provinces, of which approximately one-third are actively beekeeping and producing honey (Stubbs Citation2018). The AHB enterprise is focused on skills development, rural job creation, community empowerment, and production of high quality, raw honey (Stubbs Citation2018). The initiative equips communities to construct beehives from scrap material, as well as tower gardens and chicken coops from locally available resources (Stubbs Citation2018).

Based on the above, the aim of the study was to investigate the effects of the AHB initiative on participating households and the surrounding environment, as a case study of a rural development initiative potentially benefitting participants and the environment. These potential dual outcomes of beekeeping have not be assessed previously in South Africa. This was addressed through three objectives: (1) Determine the contributions of the AHB beekeeping initiative to rural livelihoods; (2) Gauge respondents’ perceptions about the effects of increased bee populations on crop yields; and (3) Assess whether the AHB initiative has resulted in reduced wild fire frequencies.

2. Study area

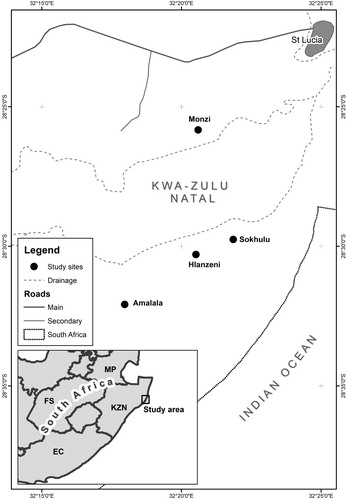

The study was conducted in four rural communities located within uThungulu district municipality, north-eastern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa (). KwaZulu-Natal province is a primary focus area of AHB because of the indigenous forests that support significant faunal and floral diversity. The sites were Hlanzeni (28°30′17.62″S 32°20′31.14″E), Sokhulu (28°29′45.29″S 32°21′51.20″E), Amalala (28°32′4.86″S 32°17′57.93″E) and Monzi (28°25′49.79″S 32°20′35.67″E). The landscape is a complex mosaic of timber plantations, subsistence households and fields, grasslands and patches of indigenous forest. The most common crops are maize, vegetables and sugar cane (uThungulu District Municipality Citation2012–Citation2017).

The climate is humid subtropical and experiences an average temperature range of 23 °C to 29 °C and average rainfall of 948 m per year (Saexplorer Citation2017). The topography of the area is varied, ranging from sea level on the coastal plain to the hilly inland areas with altitudes between 900 and 1400 m (uThungulu District Municipality Citation2012–Citation2017).

Approximately one-third of the population in the district is younger than 15 years and 61% is in the economically active age bracket of 15–60 years (Lehohla Citation2012). The adult literacy rate is approximately 76% (Lehohla Citation2012). The unemployment rates stands at about 35% (Lehohla Citation2012). Almost three-quarters (73%) of households earn less than R1 600 per month and poverty is rife, and consequently approximately 41%–60% of households in the district are dependent on state social grants for most or all of their cash income (KZN Agriculture, Environmental Affairs & Rural Development Citation2004).

3. Methods

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used. Questionnaires and interviews were used to obtain information about the effects of AHB activities on livelihoods and crop yields. Fire frequency records were provided by the Zululand fire protection association. The research conformed to the research ethics guidelines of Rhodes University and received ethics approval from the Dept of Environmental Science Ethics committee (ES18/10).

Interview participants were randomly selected from a list of beekeepers in the AHB database. Questionnaires were administered via an AHB phone application operated by the programme facilitators. Respondents answered the questions with the aid of an AHB facilitator who was able to translate the questions and responses. In total, 132 beekeepers were sampled, including productive beekeepers, i.e. those who were actively producing and selling honey, and unproductive beekeepers. The questionnaire covered: (1) Socio-economic characteristics: age, sex, income level, household size and level of education; (2) Beekeeping information: number of hives owned, mean honey yield per hive, and number of hours spent on hives (hours/week); and (3) Contribution to livelihoods: additional income received annually from beekeeping and other major sources of livelihood.

Additionally, 40 in-depth, face-to-face interviews were conducted with approximately 10 beekeepers per village, with both productive and unproductive. The in-depth interviews asked more comprehensive questions and aimed to determine the perceptions of the beekeepers on the AHB initiative and its impact on their livelihoods and the environment. The in-depth interviews also included questions about perceptions of possible changes in crop yield or size over the past few years. A Likert scale was used to determine the levels of agreement with qualitative statements pertaining to crop yield and crop size. In addition, two key informant interviews were conducted, one with Guy Stubbs, the founder of AHB, and one with Tony Roberts, the Zululand fire protection officer (both of whom agreed they could be named in research outputs).

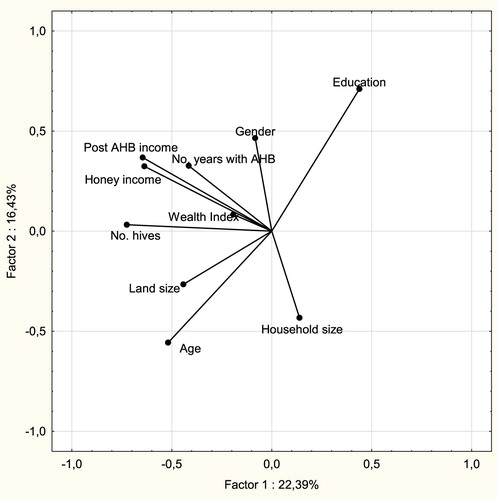

The data were analysed using R Studio and summarised using descriptive statistics. Chi-squared tests were used to test associations between beekeeper productivity and gender, changes in income class distribution before and after participation, and the challenges faced by productive compared to unproductive beekeepers. A wealth index was generated using the number of alternative livelihood strategies practiced and number of specific household assets owned. This was included in a principal component analysis (PCA) to display any relationships between the respondent characteristics, wealth and honey income. The fire frequency records were presented graphically.

The qualitative data obtained from the in-depth interviews was analysed using the Word List and Key Words in Context (KWIC) technique as described by Ryan & Bernard (Citation2003) to identify themes or patterns that describe and organise possible observations. First, a word/phrase list was generated, then the number of times each word/phrase appeared, and its context was noted and entered into an Excel spreadsheet. The themes were identified by grouping examples into categories of similar meaning. The transcribed interviews were further analysed by identifying verbatim quotes, which were used to illustrate key findings. The same technique was used to identify quotes from the key informant interviews.

4. Results

4.1. Beekeeper productivity and income

The majority of beekeepers were female and middle-aged () and 98% believed that gender does not play a role in beekeeping. In the words of a 36 year old male beekeeper: ‘Gender doesn’t make a difference when it comes to beekeeping, anyone can do it, women or men, young and old’. The average household size was approximately 7 ± 4 members, of which nearly half were children.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the respondents (n = 132).

None of the respondents had been beekeepers prior to participating in the AHB programme. However, less than one-third (29%) were productive beekeepers, in that they were actively producing and selling honey. There was no significant association between beekeeper productivity and gender (χ2 = 0.52; p = 0.47). The average honey yield was 2.7 ± 5.8 kg per hive per year and ranged from 0–16.4 kg, and the mean number of hives per keeper was 3.1 ± 2.1, ranging between 1 and 9; however, 44% had only one hive. The productive beekeepers produced only honey, none developed secondary products from beekeeping.

The main reason (55%) for not being productive was the inability to attract bees to the hive. ‘I don’t know why the hives are not catching bees, I have been a beekeeper for more than three years and still nothing. Other beekeepers have only had hives for a few months and already have bees’ (Interviewee 1, 69 year old male beekeeper). Guy Stubbs, the founder of AHB, explained a possible reason for this situation: ‘This usually occurs when another insect, like a spider, has invaded the hive. The hives need to be cleaned out and freshly waxed, this would increase the likelihood of catching bees.’

Approximately 52% of in-depth interview respondents said experienced beekeepers were more likely to be successful. ‘Experience counts a lot when it comes to beekeeping because the knowledge you get over the years is valuable’ (Interviewee 2, 76 year old female beekeeper). On the contrary, 48% said experience played no role in beekeeping, the success is all dependent on the bees. ‘Success of a beekeeper depends on the bees and how much the beekeeper loves to work with the bees, so I think motivation and effort brings a lot more success than experience’ (Interviewee 3, 60 year old female beekeeper).

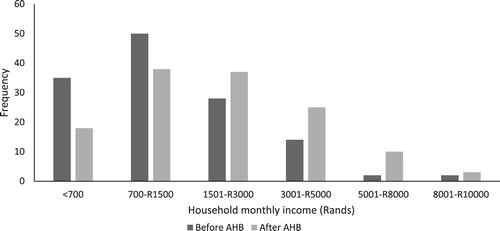

Although incomes from beekeeping were modest there was a measureable increase in beekeeper monthly household income before and after participation in the AHB programme () (χ2 = 17.0; p = 0.0045).

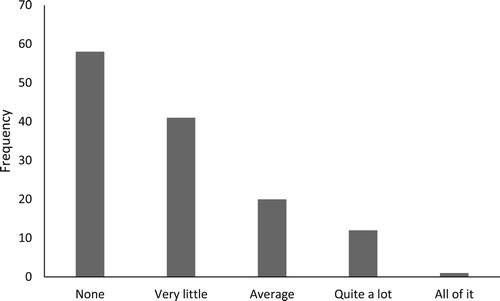

Most beekeepers received little to no income from beekeeping, whilst a few received all of their income from beekeeping (). Approximately 24% of in-depth interview respondents said that beekeeping had made a big change to their livelihood. However, most (88%) of in-depth interview respondents stated that beekeeping was a seasonal practice, and therefore they also had to have other income strategies. Besides the monetary benefits and the training and knowledge (19%) they gained from beekeeping many respondents also spoke of the intangible benefits of beekeeping and the programme:

It has influenced my livelihood a lot because being involved with AHB and the training programmes has helped me socialise. (Interviewee 4, a 52 year old female beekeeper)

Beekeeping taught me a lot about life, because it opened my mind to all the different possibilities. Now I feel like I can do anything. (Interviewee 5, a 28 year old female beekeeper)

Other than making money, I also like to use the honey to make lotions which I make for personal use and for selling. Having honey also helps me treat my flu. (32 year old female beekeeper)

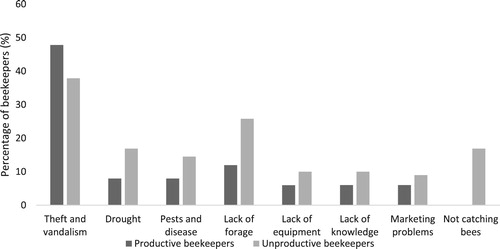

Theft and vandalism was the greatest challenge experienced by productive beekeepers, whereas unproductive beekeepers cited a range of other factors (), all of which they suffered to a higher degree than productive beekeepers (χ2 = 22.1; p = 0.0025). More unproductive beekeepers experienced challenges in comparison to productive beekeepers, with the exception of theft and vandalism. For example, ‘Theft and vandalism can be a big problem for a beekeeper. When the people steal the honey from the hives we lose a lot of money and it is difficult because you can’t do much about it, they often come at night’ (Interviewee 10, 61 year old female beekeeper).

The majority of respondents (66%) mentioned the fear of bee stings as the main negative aspect of beekeeping. For instance, interviewee 8, a 76 year old female beekeeper said: ‘When the hives are situated close to the house, they start stinging a lot. Especially when the children or the livestock disturb them’. Some respondents mentioned how their perceptions have started to change,

I used to just see bees as things that sting you, but now AHB gave me the knowledge on how to make protective clothing. Now I see that they can make you money and I can see their usefulness in the environment. (Interviewee 9, 54 year old female beekeeper)

4.2. Perceptions of the benefits of beekeeping to agriculture

Approximately two-thirds (68%) of the in-depth interview respondents said they had noticed an increase in crop yield and size in their area over the past few years. Interviewee 11, a 26 year old male beekeeper said: ‘In previous years when I made measurements it was 15% increase in crop yield and this year when I made measurements it was 35%. So you can see there was a definite increase’. However, almost half (48%) attributed the increase to better rainfall, whilst only a quarter (24%) mentioned the contribution of bee pollination. For example, interviewee 12, a 76 year old female beekeeper said; ‘The bees have helped a lot which has made me very happy because now I can see that the bees can give us good crops and honey’. The other third felt that crop yields had not changed or declined. According to Guy Stubbs: ‘There hasn’t been much training done on pollination, however there have been beekeepers who recognised the effect the bees were having on their fruits and vegetables. Some reported yields of eight times more than previous years.’

4.3. Wild fire frequency

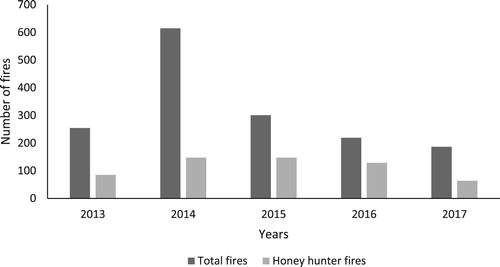

The number of forest fires and those attributed specifically to wild honey hunters decreased between 2014 and 2017 (). Whilst the total number of fires has gradually decreased, the number ascribed to honey hunter fires more than halved in the year 2017, two years after the introduction of the AHB programme. According to Zululand Fire Protection Officer, Tony Roberts: ‘The honey hunters cause a lot of fires in the timber plantations by smoking the ground and log hives, and ultimately causing uncontrolled fires.’

Figure 6. Frequency of wild fires in Zululand and those attributed to wild honey hunters (AHB started in late 2015).

Honey hunters were aware of the risk of igniting wild fires. ‘We go into the plantations, find the beehives and smoke the bees using a homemade smoker. Sometimes when the bees sting too much, we run away and leave the fire’ (Interviewee 13, 24 year old male honey hunter). However, for many it is their sole source of cash income. ‘My family gets all of the money from hunting and selling honey, we don’t have any other employment’ (Interviewee 14, 24 year old male honey hunter). Honey hunters expressed interest in converting to beekeeping with hives, for example, interviewee 14, a 24 year old male honey hunter said:

I would definitely like to become a beekeeper, I could have the hives right in backyard. Then I would not have to walk far distances to rob the wild hives and try sell honey on the side of the road.

Transitioning from honey hunting to beekeeping could definitely impact on fire frequency in the future. It could be a solution that would potentially reduce the number of honey hunters, but there will always be wild hives in the timber plantations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Contribution to livelihoods

The findings indicate that the AHB beekeeping programme had improved the livelihoods of active beekeeping households through income supplementation and skills training. Significantly more beekeepers earned a monthly income in the higher income brackets after participation in AHB compared to before. This echoes Ahmad et al. (Citation2017) who concluded that a pilot beekeeping intervention in the Chitral district of Pakistan improved the income of beneficiary households. Similarly, Kifle et al. (Citation2014) and Nel et al. (Citation2000) reported higher incomes but that beekeeping supplemented other household income as opposed to being the main contributor. Although a positive income effect was detected, it was quite low, which is likely to be a consequence of the low honey yields per hive, being only 30%–40% of those reported by projects in the Eastern Cape (Yusuf et al. Citation2018), and 15% of those in the Western Cape (Allsopp & Cherry Citation2004); this requires investigation. However, other work has shown beekeeping to a viable, fulltime livelihood for those willing to specialise (e.g. Conradie & Nortjé Citation2008; Kasumbu & Pullanikkatil Citation2019). Furthermore, there was a strong positive relationship between post-AHB income, honey income and number of years as a beekeeper with AHB, which indicates that experience influences income generated through beekeeping. Similarly, Jaffé et al. (Citation2015) found that beekeeping experience was a key factor influencing productivity and income.

Beekeeping was viewed by productive beekeepers as a favourable activity due to the quick cash flow it provided and the low level of labour required. The provision of quick cash flow enabled beekeepers to make investments into other ventures or begin savings. The AHB programme, and many beekeeping programmes alike, offer extension services in the form of formal savings groups that teach participants how to save, lend, borrow and invest their money (Tobey & Torell Citation2006; Ingram & Njikeu Citation2011; Amulen et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, many of the beekeepers affirmed that beekeeping is not a labour intensive activity in comparison to other agricultural activities (Al-Ghamdi et al. Citation2017). The hives do not need to be attended daily and only require a few hours during hive construction, harvesting time, and routine maintenance and cleaning (Fabricius et al. Citation2004). This makes it a viable strategy for all ages and abilities (Mujuni et al. Citation2012; Peter Citation2015). The majority of the beekeepers were female, as was also reported by Yusuf et al. (Citation2018) for the Eastern Cape projects, and there was no association between gender and productivity. This is in contrast to Gebrehiwot (Citation2015) and Hecklé et al. (Citation2018), who indicated that women were less likely to participate in beekeeping. In some contexts, women are commonly excluded from beekeeping due to traditional beliefs or social norms and perceived risks (Qaiser et al. Citation2013; Hecklé et al. Citation2018).

If beekeeping is to be effectively implemented as a poverty alleviation strategy, there are a number of constraints that need to be addressed. Theft and vandalism were the biggest challenges facing the beekeepers, especially productive beekeepers. This was because productive hives contain honey which could be stolen, whilst unproductive hives would be empty. Findings were concurrent with Masehela (Citation2017) who found vandalism to be the main reason for colony loss, and also Conradie & Nortjé (Citation2008) and Yusuf et al. (Citation2018) who both observed vandalism and theft as major setbacks to beekeepers. Theft includes theft of the entire hives or theft of the honey. Despite placing preventative measures in place, it often cannot be avoided and results in income and infrastructure losses for beekeepers (Masehela Citation2017). Most small-scale beekeepers lack the resources to put adequate measures in place to monitor their hives and therefore may become discouraged by theft, such that some abandon beekeeping altogether (Masehela Citation2017). According to Masehela (Citation2017) the magnitude of theft and vandalism is dependent on the position and visibility of the hives; beekeepers who situate their hives in distant sites experience higher risks. Preventative measures include placing hives closer to beekeepers’ homesteads, placing fencing around the hives, using mesh cages, and placing hives in sheltered, less visible locations (Hill & Webster Citation1995; Conradie & Nortjé Citation2008; Masehela Citation2017).

Drought, lack of forage, pests and disease and not catching bees were additional challenges faced by unproductive beekeepers and to a smaller extent by productive beekeepers. This echoes findings from elsewhere in South Africa (e.g. Yusuf et al. Citation2018) and the continent (Beyene & Verschuur Citation2014; Gebrehiwot Citation2015). The health of honey bees is directly dependent on availability and accessibility of forage, because bees require a diverse diet and access to a variety of pollen to synthesise detoxifying enzymes and for their immune systems (Alaux et al. Citation2010). Nectar is also an important source of energy for bees (Nicolson Citation2011). A shortage is often a result of deforestation for timber, fuelwood or expansion of agricultural land (Beyene & Verschuur Citation2014; Yusuf et al. Citation2018). Drought and adverse climatic conditions are additional contributing factors, because of the impact that lack of rain and dry conditions have on honey bee forage. A dry climate reduces the production of flowers and nectar, which leaves the bees impoverished and unable to produce honey (Le Conte & Navajas Citation2008). In extreme conditions, bees may abscond from drought affected areas to seek more favourable conditions (Le Conte & Navajas Citation2008). This often forces beekeepers to relocate their hives to sites with more forage, which in turn makes them more vulnerable to theft and vandalism. Interventions to ensure adequate forage include conservation of natural vegetation, planting pollen and nectar rich species, enforcing timber harvesting quotas, and rehabilitation of degraded lands or forests (Yirga & Teferi Citation2010). Furthermore, pests and diseases can cause major damage to bee colonies, so it is important for beekeepers to monitor their hives (Yirga & Teferi Citation2010). According to Yirga & Teferi (Citation2010), common honey bee pests include ants, spiders, birds and lizards. Beekeepers may not recognise that these pests have infested a hive and are one of the main factors inhibiting bees from colonising a hive. Not being able to catch bees was a frequent lament by unproductive beekeepers, many of whom were becoming despondent. This finding corroborates Hecklé et al. (Citation2018) who reported that empty beehives and pests led to low productivity or abandonment of beekeeping. There is obvious scope for the AHB or more productive beekeepers in the communities to help newly established beekeepers with brood colonies.

Lack of knowledge and equipment and marketing problems were the least reported challenges. This is in contrast to previous work (Kinati et al. Citation2012; Gebrehiwot Citation2015; Hecklé et al. Citation2018; Yusuf et al. Citation2018). This is likely due to the positive influence of the AHB programme. Kuboja et al. (Citation2017) report that extension services and access to training on improved beekeeping management practices were the main factors that improved economic efficiency of small-scale beekeepers in Tanzania. This is further substantiated by Amulen et al. (Citation2017) who attributed the inability of beekeeping to improve livelihoods to a lack of training and equipment. AHB facilitates knowledge development through continuous training and support programmes which teach a variety of skills, from making protective clothing and smokers to constructing a beehive. Aspirant beekeepers who complete the first few stages of the training programme are given a flatpack, which provides all the tools necessary to construct a hive.

5.2. Perceived effects on crops

The majority of respondents stated that they had experienced an increase in crop yield and crop size. However, most did not attribute this to the increasing honeybee populations in the area. This is not surprising because the manifestation and magnitude of any benefits will depend on the type of crop grown, and more specifically whether it is wind or insect pollinated. Maize, the primary crop in the area, is wind pollinated. Whilst some mentioned the positive impacts of the bees on crop pollination, many beekeepers seemed unaware of the pollination services that bees provide, echoing the observations of Bradbear (Citation2009). The AHB initiative may indeed have had a positive impact on the perceived crop yield and size increases, but it is unlikely to be the sole reason. The impact on the crops could be from incidental pollination services as a result of increased beekeeping activity in the area (Kasina et al. Citation2009). There is potential for these increases in crop quantity and quality to improve food security (van der Sluijs & Vaage Citation2016). However, growing evidence indicates that wild pollinators provide more effective crop pollination than honeybees, which suggests that a combination of diverse pollinators would provide better pollination than relying solely on honeybees (Aebi et al. Citation2012; Garibaldi et al. Citation2013; Melin et al. Citation2014). Further research is needed to determine how pollination from beekeeping practices impacts subsistence agriculture.

5.3. Beekeeping and wild fires

The results show a declining incidence of forest fires and the fraction attributed to wild honey hunters. However, given that there are only two-year’s data since the AHB programme commenced and that a diverse number of factors influence honey hunting and the frequency of wild fires independently, it would be unwise to conclude that the beekeeping programme alone affected the decrease in fire frequency. The positive outcome is likely to be a result of a combination of the influence of the AHB initiative, the efforts of the Zululand Fire Protection Association and other factors beyond the scope of this study. AHB’s influence is a result of incentives to convert to beekeeping and providing honey hunters with an opportunity to do so through training and provision of equipment. Beekeeping is an attractive activity compared to honey hunting, as it alleviates uncertainty, requires less time, and overcomes the unpredictability associated with honey hunting (Lowore et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, the initiative focuses on training and knowledge development of honey hunters and children, which aims to educate them about the importance of honeybees and conserving the environment (Stubbs Citation2018). Through this, honey hunters learn how to hunt honey in a more environmentally friendly way, e.g. not destroying the whole colony and not setting uncontrolled fires. Okoye & Agwu (Citation2008) showed the importance of this, because activities associated with honey hunting, including leaving of fires, can have negative impacts on forests. Honey hunters are often overlooked by extension services provided to beekeepers (Bradbear Citation2009), whereas the regular training and information provided by AHB also target honey hunters.

6. Conclusion

Small-scale beekeeping had a positive impact on many participant households’ through income supplementation and indirect benefits. Many of the latter were expressed in more qualitative terms, such as appreciation of the social networks developed when attending AHB training courses, the relative ease of beekeeping compared to agricultural work and the low cost outlay. There was no gender difference regarding beekeeping adoption or productivity in the study communities. The main challenges experienced by the beekeepers included theft and vandalism, drought, lack of forage, pests and disease and not catching bees. The last was particularly demotivating to newly trained beekeepers who had high hopes immediately after the training. These challenges could be addressed through appropriate and ongoing training and assistance to share hives with new beekeepers. Furthermore, the pollination services from the managed bees were perceived by some to have increased crop yields and size. The extension services of AHB had a positive impact on forest conservation through the reduction of wild fires. These multiple benefits suggest that AHB could provide a model for similar programmes elsewhere seeking to improve livelihoods and conservation via the multiple benefits of small-scale beekeeping.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are due to Guy Stubbs, African Honey Bee and Tony Roberts for making this research possible and to Daniel Schormann for creating the application used for data collection. This research was funded by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant number 84379). Any opinion, finding, conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the authors and the NRF does not accept any liability in this regard.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aebi, A, Vaissière, B, van Engelsdorp, D, Delaplane, K, Roubik, D & Neumann, P, 2012. Back to the future: Apis versus non-Apis pollination—A response to Ollerton et al. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 27(3), 142–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.11.017

- Ahmad, T, Shah, G, Ahmad, F, Partap, U & Ahmad, S, 2017. Impact of apiculture on the household income of rural poor in mountains of Chitral district in Pakistan. Journal of Social Sciences (COES&RJ-JSS) 6(3), 518–31. doi: 10.25255/jss.2017.6.3.518.531

- Alaux, C, Ducloz, F, Crauser, D & Le Conte, Y, 2010. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biology Letters 6(4), 562–5. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0986

- Al-Ghamdi, A, Adgaba, N, Herab, A & Ansari, M, 2017. Comparative analysis of profitability of honey production using traditional and box hives. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 24(5), 1075–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.01.007

- Allsopp, MH & Cherry, M, 2004. An assessment of the impact on the bee and agricultural industries on the Western Cape of the clearing of certain Eucalyptus species using questionnaire and survey data. PPRI, Pretoria.

- Allsopp, M, de Lange, W & Veldtman, R, 2008. Valuing insect pollination services with cost of replacement. PLoS ONE 3(9), e3128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003128

- Amulen, D, D’Haese, M, Ahikiriza, E, Agea, J, Jacobs, F, de Graaf, D, Smagghe, G & Cross, P, 2017. The buzz about bees and poverty alleviation: Identifying drivers and barriers of beekeeping in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 12(2), e0172820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172820

- Angelsen, A, Jagger, P, Babigumira, R, Belcher, B, Hogarth, NJ, Bauch, S, Börner, J, Smith-Hall, C & Wunder, S, 2014. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: A global-comparative analysis. World Development 64(S1), S12–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.006

- Beyene, T & Verschuur, M, 2014. Assessment of constraints and opportunities of honey production in Wonchi district South West Shewa Zone of Oromia, Ethiopia. American Journal of Research Communication 2(10), 342–53.

- Bradbear, N, 2004. Beekeeping and sustainable livelihoods. Diversification booklet 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Bradbear, N, 2009. Bees and their role in forest livelihoods. Diversification booklet 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Conradie, B & Nortjé, B, 2008. Survey of beekeeping in South Africa. CSSR Working Paper no. 221. https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/item/22325/Conradie_Survey_beekeeping_in_2008.pdf.

- Fabricius, C, Koch, E, Turner, S & Magome, H, 2004. Rights resources and rural development. Taylor and Francis, Hoboken.

- Garibaldi, L, Steffan-Dewenter, I, Winfree, R, Aizen, M, Bommarco, R, Cunningham, SA, Kremen, C, Carvalheiro, LG, Harder, LD, Afik, O, Bartomeus, I, Benjamin, F, Boreux, V, Cariveau, D, Chacoff, NP, Dudenhoffer, JH, Freitas, BM, Ghazoul, J, Greenleaf, S, Hipolito, J, Holzschuh, A, Howlett, B, Isaacs, R, Javorek, SK, Kennedy, CM, Krewenka, KM, Krishnan, S, Mandelik, Y, Mayfield, MM, Motzke, I, Munyuli, T, Nault, BA, Otieno, M, Petersen, J, Pisanty, G, Potts, SG, Rader, R, Ricketts, TH, Rundlof, M, Seymour, CL, Schuepp, C, Szentgyorgyi, H, Taki, H, Tscharntke, T, Vergara, CH, Viana, BF, Wanger, TC, Westphal, C, Williams, N & Klein, AM, 2013. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 339(6127), 1608–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1230200

- Gebrehiwot, N, 2015. Honey production and marketing: The pathway for poverty alleviation the case of Tigray Regional State, Northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Business Economics and Management Research 5(6), 342–63.

- Girma, J & Gardebroek, C, 2015. The impact of contracts on organic honey producers’ incomes in Southwestern Ethiopia. Forest Policy & Economics 50, 259–68. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2014.08.001

- Goldblatt, A, 2015. Agriculture: Facts and trends South Africa. World Wide Fund for Nature, Cape Town.

- Hecklé, R, Smith, P, Macdiarmid, J, Campbell, E & Abbott, P, 2018. Beekeeping adoption: A case study of three smallholder farming communities in Baringo County, Kenya. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics 119(1), 1–11.

- Hill, D & Webster, T, 1995. Apiculture and forestry (bees and trees). Agroforestry Systems 29(3), 313–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00704877

- Hilmi, M, Bradbear, N & Mejia, D, 2011. Beekeeping and sustainable livelihoods. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Ingram, V & Njikeu, J, 2011. Sweet, sticky, and sustainable social business. Ecology and Society 16(1), 37. [online]. doi: 10.5751/ES-03930-160137

- Jaffé, R, Pope, N, Carvalho, A, Maia, U, Blochtein, B, de Carvalho, C, Carvalho-Zilse, G, Freitas, B, Menezes, C, de Fátima Ribeiro, M, Venturieri, G & Imperatriz-Fonseca, V, 2015. Bees for development: Brazilian survey reveals how to optimize stingless beekeeping. PLoS ONE 10(3), e0121157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121157

- Kasina, J, Mburu, J, Kraemer, M & Holm-Mueller, K, 2009. Economic benefit of crop pollination by bees: A case of Kakamega small-holder farming in Western Kenya. Journal of Economic Entomology 102(2), 467–73. doi: 10.1603/029.102.0201

- Kasumbu, A & Pullanikkatil, D, 2019. Busy as a bee: Industrious bees in Malawi. In Pullanikkatil, D & Shackleton, C (Eds.), Poverty reduction through non-timber forest products: Personal stories. Springer, Heidelberg. pp. 91–7.

- Kifle, T, Hora, K & Merti, A, 2014. Investigating the role of apiculture in watershed management and income improvement in Galessa protected area, Ethiopia. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 3(5), 380. doi: 10.11648/j.aff.20140305.18

- Kinati, C, Tolemariam, T, Debele, K & Tolosa, T, 2012. Opportunities and challenges of honey production in Gomma district of Jimma Zone, South-west Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development 4(4), 85–90.

- Kuboja, N, Isinika, A & Kilima, F, 2017. Determinants of economic efficiency among small-scale beekeepers in Tabora and Katavi Regions, Tanzania: A stochastic profit frontier approach. Development Studies Research 4(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1080/21665095.2017.1355738

- KZN Agriculture, Environmental Affairs and Rural Development, 2004. KwaZulu-Natal state of the environment 2004. Vulnerability specialist report. Pietermaritzburg: KZN Agriculture, Environmental Affairs and Rural Development.

- Le Conte, Y & Navajas, M, 2008. Climate change: Impact on honey bee populations and diseases. Revue Scientifique et Technique (Paris) 27(2), 485–510. doi: 10.20506/rst.27.2.1819

- Lehohla, P, 2012. Census 2011 municipal report. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Lowore, J, Meaton, J & Wood, A, 2018. African forest honey: An overlooked NTFP with potential to support livelihoods and forests. Environmental Management 62(1), 15–28. doi: 10.1007/s00267-018-1015-8

- Masehela, T, 2017. An assessment of different beekeeping practices in South Africa based on their needs (bee forage use), services (pollination services) and threats (hive theft and vandalism). PhD, Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

- Meddour-Sahar, O, Meddour, R, Leone, V, Lovreglio, R & Derridj, A, 2013. Analysis of forest fires causes and their motivations in Northern Algeria: The Delphi method. iForest – Biogeosciences and Forestry 6(4), 247–54. doi: 10.3832/ifor0098-006

- Melin, A, Rouget, M, Midgley, J & Donaldson, J, 2014. Pollination ecosystem services in South African agricultural systems. South African Journal of Science 110(11/12), 1–9. doi: 10.1590/sajs.2014/20140078

- Mujuni, A, Natukunda, K & Kugonza, D, 2012. Factors affecting the adoption of beekeeping and associated technologies in Bushenyi district, Western Uganda. Livestock Research for Rural Development 24(8), 133. [online].

- Musinguzi, P, Bosselmann, AS & Pouliot, M, 2018. Livelihoods-conservation Initiatives: Evidence of Socio-economic impacts from organic honey production in Mwingi, Eastern Kenya. Forest Policy & Economics 97, 132–45. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2018.09.010

- Nel, E, Illgner, P, Wilkins, K & Robertson, M, 2000. Rural self-reliance in Bondolfi, Zimbabwe: The role of beekeeping. The Geographical Journal 166(1), 26–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4959.2000.tb00004.x

- Nicolson, S, 2011. Bee food: The chemistry and nutritional value of nectar, pollen and mixtures of the two. African Zoology 46(2), 197–204. doi: 10.1080/15627020.2011.11407495

- Okoye, C & Agwu, A, 2008. Factors affecting agroforestry sustainability in bee endemic parts of Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 26(2), 132–54. doi: 10.1080/10549810701879685

- Park, M & Youn, Y, 2012. Traditional knowledge of Korean native beekeeping and sustainable forest management. Forest Policy and Economics 15, 37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2011.12.003

- Paumgarten, F, Kassa, H, Zida, M & Moeliono, M, 2012. Benefits, challenges, and enabling conditions of collective action to promote sustainable production and marketing of products from Africa’s dry forests. Review of Policy Research 29, 229–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2011.00549.x

- Peter, L, 2015. Socio-economic factors influencing apiculture in the Eastern Cape Province. MSc Agriculture, Fort Hare, East London South Africa.

- Pywell, R, Heard, M, Woodcock, B, Hinsley, S, Ridding, L, Nowakowski, M & Bullock, J, 2015. Wildlife-friendly farming increases crop yield: Evidence for ecological intensification. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282(1816), 20151740. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1740

- Qaiser, T, Tahir, A, Taj, S & Ali, M, 2013. Benefit-cost analysis of apiculture enterprise: A case study in district Chakwal, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research 26(4), 295–7.

- Ribeiro, NS, Snook, LK, Nunes de Carvalho Vaz, IC & Alves, T, 2019. Gathering honey from wild and traditional hives in the Miombo Woodlands of the Niassa National Reserve, Mozambique: What are the impacts on tree populations? Global Ecology & Conservation 17, e00552. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00552

- Ryan, G & Bernard, H, 2003. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 15(1), 85–109. doi: 10.1177/1525822X02239569

- SABIO, 2008. NAMC report. The South African beekeeping industry. SABIO, Randburg.

- Saexplorer, 2017. Empangeni climate. [Online]. http://www.saexplorer.co.za/south-africa/climate/empangeni_climate.asp Accessed 23 March 2018.

- Senapathi, D, Biesmeijer, J, Breeze, T, Kleijn, D, Potts, S & Carvalheiro, L, 2015. Pollinator conservation—the difference between managing for pollination services and preserving pollinator diversity. Current Opinion in Insect Science 12, 93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2015.11.002

- Shackleton, C & Shackleton, S, 2004. The importance of non-timber forest products in rural livelihood security and safety nets: A review of evidence from South Africa. South Africa Journal of Science 100, 658–64.

- Stubbs, G, 2018. African honey bee. [Online]. https://africanhoneybee.co.za/ Accessed 14 March 2018.

- Tesfaye, B, Begna, D & Eshetu, M, 2017. Beekeeping practices, trends and constraints in Bale, South-Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Fisheries and Livestock Production 5(1), 1–9.

- Tobey, J & Torell, E, 2006. Coastal poverty and MPA management in Mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar. Ocean and Coastal Management 49(11), 834–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2006.08.002

- uThungulu District Municipality, 2012–2017. Uthungulu district municipality integrated development plan. uThungulu District Municipality, Richards Bay.

- van der Sluijs, J & Vaage, N, 2016. Pollinators and global food security: The need for holistic global stewardship. Food Ethics 1(1), 75–91. doi: 10.1007/s41055-016-0003-z

- Yirga, G & Teferi, M, 2010. Participatory technology and constraints assessment to improve the livelihood of beekeepers in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia. Momona Ethiopian Journal of Science 2(1), 76–92. doi: 10.4314/mejs.v2i1.49654

- Yusuf, SF, Cishe, E & Skenjana, N, 2018. Beekeeping and crop farming integration for sustaining beekeeping cooperative societies: A case study of Amathole district, South Africa. Geojournal 83, 1035–51. doi: 10.1007/s10708-017-9814-7