ABSTRACT

Tourism and tourism development have the potential to make a positive impact on a region’s economic development and sustainability. In this sense, the central Karoo has a great deal to offer heritage tourists. As there are numerous battlefield sites associated with the South African War (1899–1902) (previously the Anglo-Boer War) the central Karoo offers a unique development opportunity to demarcate a designated battlefield route dedicated to the war. This study investigated the potential for the development of the proposed route by involving potential stakeholders (specifically product owners and government officials) on the route. The study was qualitative, and 33 interviews were conducted. Thematic content analysis was used to analyse the data. The main findings indicate a need for the development of the route and the establishment of a South African War Battlefields Route Destination Marketing Organisation (DMO).

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the pillars for economic growth in line with the New Growth Path, as declared by the South African Government. The creation of 225 000 jobs and increasing the tourism economic contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of South Africa to R499 billion by the year 2020, are some of the outcomes the National Department of Tourism (NDT) are envisioning (Domestic Tourism Growth Strategy Citation2012–Citation2020, no date:1). According to the Domestic Tourism Growth Strategy 2012–2020, the NDT is committed to the development of tourism in lesser-known regions of South Africa. One of these lesser-known regions is the Karoo.

The name ‘Karoo’ was derived from the Khoikhoi word ‘garob’ meaning ‘dry place’ (Schoeman, Citation2013b:8; Allen, Citation2015:35). Straddling four provinces (Western Cape, Eastern Cape, Northern Cape and Free State), the Karoo stretches about 600 km from west to east and 600 km from north to south in central South Africa. It is an arid area with stark beauty, which appeals to many tourists interested in arid areas (Atkinson, Citation2008; Hattingh, Citation2016:1; SAT, Citationno date).

The National Heritage and Cultural Tourism Strategy 2012, which is informed by the White Paper on the Development of Tourism in South Africa (1996), constructed a vision ‘to realise the global competitiveness of South African heritage and cultural resources through product development for sustainable tourism and economic development’ (NDTRSA, Citation2012:10). Heritage tourism, according to the Tourism White Paper (1996), can be identified as scenic parks, sites of scientific and historical importance, national monuments and historic buildings (NDTRSA, Citation2012:6).

The expansion opportunities for heritage tourism in the central Karoo region are endless and offer a plethora of undeveloped market segments such as the battlefield sites dating from the South African War (11 October 1899, to 31 May 1902), as well as rock art and architectural heritage. As there is increased interest in the South African War, both nationally and internationally, it offers the opportunity for tourism development in the central Karoo (Atkinson, Citation2016a:9; Hattingh, Citation2016; Colesberg - Experience the Northern Cape, South Africa, Citation2019; Karoobattlefields, Citationno date; Project, Citationno date).

The South African War (1899–1902) had a devastating and long-lasting impact on the economic, social, political and historical context of South Africa (Wessels, Citation1991:8; Kruger, Citation1999:46). Kruger (Citation1999:3) states that the South African War left no part of the South African population unaffected. It was fought across large parts of the then Cape and Natal Colonies, as well as the two independent Boer Republics of the Orange Free State and Transvaal. Due to the large theatre of war, there are numerous battle sites spread throughout South Africa. Some of these sites have been developed into tourist attractions e.g. The KZN Battlefields Route, incorporating Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift as part of the remembrance of the Anglo-Zulu Wars, whilst Colenso and Spioenkop are commemorating the South African War. Another example is the N12 Battlefields Route in the Northern Cape, which incorporates the battles of Belmont, Graspan, Modder River and Magersfontein (see Van der Merwe, Citation2019). As the South African War escalated the theatre of action also moved into the Cape Colony. A number of skirmishes and battles took place in the Cape Colony and the theatre of battle encapsulated large parts of the central Karoo. As indicated before, most of the battlefield sites in the central Karoo are not developed as tourist attractions.

There is worldwide an increased interest in so-called ‘dark tourism’ (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009:5; Dark Tourism: The Demand for new Experiences, Citation2017; Boateng, Okoe & Hinson, Citation2018:104). Dark tourism can be described as special interest tourism that involves tourists visiting sites of death, disaster and depravity (Lennon & Foley, Citation2000:13; Moeller, Citation2005:10; Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009:5; Special Interest Tourism, Citation2016). Battlefield tourism is a component of dark tourism that involves tourists travelling to war sites, battlefields and cemeteries (Moeller, Citation2005:6; Van der Merwe, Citation2014).

Previous studies on battlefield tourism include the study of Dunkley et al. (Citation2011:860–868) on the motivations and experiences of tourists visiting World War One battlefields. Other research includes that of Seaton (Citation2000:63–77) which focused on the perspectives and experiences of battlefield tourists visiting the Western Front of the First World War, particularly the Somme and in Flanders. Seaton’s investigation ‘hopefully, confirms the utility of meaning rather than motivation as a way of understanding tourist behaviour. It suggests that military tourists are less driven by discrete forces, rather than impelled by meaning systems that are produced socially’ (Seaton, Citation2000:75). In the South African context, previous research on battlefield routes include the study of Van der Merwe (Citation2014) whom investigated the potential of heritage tourism at the battlefields, in the Dundee vicinity in South Africa. Van der Merwe (Citation2014), analysed the economic opportunities for battlefield- heritage tourism in South Africa by examining the battlefields route within KwaZulu-Natal. Van Der Merwe (Citation2014:136) concluded that whilst battlefields tourism in South Africa can be an asset and a lever for local economic development, the situation in the KwaZulu-Natal region is currently in a state of disarray and decline. Venter (Citation2011) investigated Battlefield tourism in the South African context and found that battlefield routes need to be become self-sustainable and suggests that battlefield tourism should be incorporated into tourism packages.

Numerous research have also been conducted on the historical context of the South African War (Maurice, Citation1906; Breytenbach, Citation1977; Pakenham, Citation1979; Constantine, Citation1996; Pretorius, Citation1998; Hattingh & Wessels, Citation2000). The South African War provides the central Karoo with the opportunity to not only advance heritage tourism in the region, but Dark Tourism also. The main objective of the study was to explore the developmental perspectives for the South African War Battlefields Route in the central Karoo. The motivation, opinions, and demographic profile of tourists were not measured as the study was written from a supply-side perspective.

1.1. Battlefield tourism: profiling the South African War

Dark tourism is experiencing an increase in popularity worldwide (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009:5; Dark Tourism: The Demand for new Experiences, Citation2017; Acha-Anyi, Citation2018:374; Boateng et al., Citation2018:104). This is also true for South Africa as there is an increased interest in visiting places associated with war and destruction. ‘Dark’ in the context of dark tourism is not meant literally but metaphorically, as ‘a dark chapter of history’. The dark aspects of history and humanity are of particular interest to some tourists. Dark tourism was first coined by Foley & Lennon (Citation1996), and the term later became the title of their book ‘Dark Tourism’ (Lennon & Foley, Citation2000; Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009:12). Stone (Citation2006:146) states that dark tourism can be defined as apparent disturbing practices and morbid products (and experiences) within the tourism domain. According to Acha-Anyi (Citation2018:374), dark tourism involves travelling to places associated with death and suffering.

Dark tourism thus involves visitation to battlefields, murder and massacre sites, places where celebrities died, graveyards and internment sites, memorials, events and exhibitions featuring relics and reconstruction of death (Miles, Citation2014:136; Dark Tourism: The Demand for new Experiences, Citation2017). Dark tourism is also referred to as Thana tourism (Seaton, Citation1996; Lennon & Foley, Citation2000; Podoshen, Citation2013:264; Miles, Citation2014:135; Chang, Citation2017:1), fatal attraction, death spots (Rojek, Citation1993), heritage that hurts (Beech, Citation2000:30) or atrocity heritage tourism (Ashworth, Citation2004:95; Moeller, Citation2005:14). According to Dunkley et al. (Citation2011:860), dark tourism is a practice which is on the increase globally.

Popular examples of dark tourism include tourists viewing sites of the brutality of former battlefields in northern France, tourists purchasing memorabilia of atrocities at Ground Zero in New York (previously the World Trade Centre) and tourists viewing New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Ground Zero in New York attracted 3.6 million visitors in 2002 whilst prior to the events on 11 September 2001, only 1.8 million people visited the World Trade Centre (Dunkley, Citation2007:2; Ground Zero & the phenomena of ‘Dark Tourism’ - The Official Globe Trekker Website, Citationno date).

One of the components of dark tourism is battlefield tourism and sites or destinations associated with war (Dunkley et al., Citation2011:860; Miles, Citation2014:137; Chang, Citation2017:1). According to Light (Citation2017:276), research into tourism at battlefields and sites associated with war is substantial. It probably constitutes ‘the largest single category of tourist attractions in the world’ (Smith, Citation1998:205; Stone & Sharpley, Citation2008:574). For this apparent reason, battlefield tourism has become an important sector of tourism today. The following section will provide further insight into battlefield tourism.

A battlefield could be defined as ‘the area of land over which a battle was fought, and significant related activities occurred. A battle is an engagement involving wholly or largely military forces that had the aim of inflicting lethal force against an opposing army’ (Historic Scotland (undated) Inventory of Historic Battlefields, Citation2009:29; Miles, Citation2012:59).

According to Dunkley et al. (Citation2011:860), and Van der Merwe (Citation2014:123), battlefield tourism includes ‘visiting war memorials and war museums, “war experiences”, battle re-enactments and the battlefield’. Misztal (Citation2003:130–131) further states that battlefield tourism offers sites of cultural memory where ‘memory becomes institutionalised through cultural means, such as commemorative rituals, memorials, and museums’. Moeller (Citation2005:6) defines battlefield tourism as specifically focusing on famous war sites, battlefields, and cemeteries.

At first, war and tourism do not seem to be a successful combination, however as mentioned, despite the horrors of death and destruction the memorabilia of warfare and allied products probably constitutes the largest single category of tourist attractions in the world (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009:186). Sir Winston Churchill (a British politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 and again from 1951 to 1955) called battlefields the ‘punctuation marks’ of history (Miles, Citation2012:2).

Battlefield tourism has attracted attention from early times (Sharpley & Stone, Citation2009:186). During the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, which heralded the defeat of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, large numbers of spectators visited the battlefield while fighting took place (Seaton, Citation1996:234; Holguin, Citation2005:1400; Moeller, Citation2005:18; Klein, Citation2016). In 1854, the first tour to Waterloo took place, thus establishing battlefield tourism as a new kind of attraction (Seaton, Citation1999:139). Waterloo remained Belgium’s most popular tourist attraction throughout the 19th and 20th centuries (Seaton, Citation1999:130). Ryan (Citation2007:13) states that battlefield sites can attract several hundreds of thousands of tourists each year.

Extensive research has been undertaken on the battlefields of World War 1 (WW1) (1914–1918) and with 2014 marking the centenary of WW1, large numbers of tourists were visiting battlefield sites around the world (Clarke & Eastgate, Citation2011; Winter, Citation2012). Civil War battlefield sites are also currently extremely popular with tourists with the site at Gettysburg (1863) attracting over 3 million visits a year (Miles, Citation2012:4). Destinations such as Southeast Asia, Balkan Europe, and the Middle East have contributed to and widen the possibility of what is a booming sector of the international tourist market for war sites (Moeller, Citation2005:19). According to Marais (Citation2017:42) cemetery tourism is also growing in popularity around the world. The following section contains a short history of the South African War (1899–1902).

The South African War (previously Anglo-Boer War), was fought between the British Empire and the two independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State (OVS) and the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR), otherwise known as the Transvaal (Scholtz, Citation2000:17; Van Zyl et al., Citation2012:10). The war was not considered as a large-scale war compared to world standards. However, according to Nothling (Citation1998:2), the South African War had severe impacts on cultural and social change within South Africa. The casualties on the Boer side was 3 997, whilst on the British side it was 7 792 individuals on the battlefield itself (Wessels, Citation1991:46).

The main reason for the outbreak of the war was British imperialism which, after gold was discovered in 1886 in the then Transvaal, reached its pinnacle. With Great Britain positioning troops along the borders of the Orange Free State and Transvaal during 1898–1899, the two independent Boer republics sent an ultimatum to Great Britain. This ultimatum stated that Great Britain had to retract the troops from their borders, or a war would ensue. The British Empire did not adhere to the ultimatum. Failing to comply with the ultimatum, the Boers declared the South African War on 11 October 1899 (Reitz, Citation1929:23; Breytenbach, Citation1978:138; Pakenham, Citation1979:1; Wessels, Citation1991:2; Nothling, Citation1998:6; Van den Berg, Citation1998:11; Van Zyl et al., Citation2012:17; Von der Heyde, Citation2013:21, Citation2017:13 111; Allen, Citation2015:198; Grobler, Citation2017:1, Citation2018:17; Hattingh, Citationno date:2). The war concluded on 31 May 1902, when a condition of surrender was signed at Melrose House in Pretoria. The Orange Free State and Transvaal surrendered to Great Britain and were colonised - thereby losing their independence. The following section alludes to the central Karoo as a tourism node.

1.2. The central Karoo as a tourism node

In several regions of the world, notably Australia and the United States of America, desert tourism has grown steadily because of a post-modern fascination with remoteness, barrenness, silence, and solitude. ‘Desert tourism’ attracts people who enjoy visiting unusual places, which offer location-specific attractions or activities. The central Karoo is South Africa’s own desert (Atkinson, Citation2016b:199). The impression of the central Karoo has been that the region is a vast, hot, uncomfortable, and a boring stretch of empty countryside. However, this impression of the central Karoo appears to be changing with people finding the Karoo more appealing and interesting than before (Schoeman, Citation2013a:8; Atkinson, Citation2016b:199; Hattingh, Citation2016:ii).

It is a vast expanse of wide-horizons, rocky mountains and narrowed hills, that contain an ancient inland seabed and a spectacular night sky. Other desert tourism regions like the Australian Outback, Arizona, and New Mexico in the United States are closely related to the central Karoo and offers similar experiences (Atkinson, Citation2016b:199; The magical Great Karoo, Citation2017). According to Willis (Citation1998:48) the Karoo is one of the world’s largest arid plains. The area is fossil-rich with the largest variety of succulents found anywhere on Earth. More than 9 000 species of plants can be found in the Karoo. In the central Karoo, some of the world’s most important archaeological sites are situated (including stone-age sites and Bushmen engravings) (Willis, Citation1998:49; Karoo History Ganora Shelters, Citation2015; Central Karoo, Citation2017; Central Karoo Information, Citationno date).

The central Karoo region is home to numerous conflicts. Many war memorials, British blockhouses, forts and gravesites dating back to the South African War are reminders of the history captured in the region (Marais, Citation2017:38). Corbelled houses, water mills and old bridges all are examples of long-forgotten vernacular, industrial architecture and engineering which can be viewed in the central Karoo (Schoeman, Citation2013b:9).

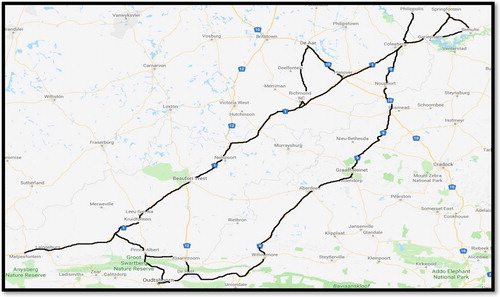

Throughout the central Karoo, tourist offices, museums, and regional information centres provide details for tourists in search of more knowledge on this region. For the tourist in search of battlefield tourism sites, there is plenty on offer all the way from Cape Town to the Orange River (Willis, Citation1998:49). Therefore, a battlefields route could potentially assist in advancing heritage tourism in the central Karoo. This proposed battlefield route encompasses the major South African War tourist attractions in the central Karoo, and will add to the tourism portfolio of the area. The following cities and towns form part of the proposed South African War Battlefields Route in the central Karoo: Springfontein, Bethulie, Philippolis, Norvalspont, Colesberg, Noupoort, Middelburg, Graaf-Reinet, Aberdeen, Willowmore, Klaarstroom, Oudtshoorn, Laingsburg, Matjiesfontein, Prince Albert, Beaufort West, Richmond, Hanover, Deelfontein and De Aar. Refer to for an illustration of the proposed battlefields route.

Map 1. Map of the proposed South African War Battlefields Route in the central Karoo (Indicated by the thick black line). Source: (Google Maps, Citation2018).

2. Materials and methods

The study adhered to an ontological perspective of constructionism, which entails the belief that reality is socially constructed through social actors and their individual perceptions in a particular context. The researcher(s) believe that knowledge does not exist outside people, but is actively created by individuals through meaningful experiences. It is for this reason that the study adhered to interpretivism (Bryman et al., Citation2014:17; Chowdhury, Citation2014:433; Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016:28; Maree, Citation2016:60; Walliman, Citation2016:12). The researcher’s ontological and epistemological views are closely related, as they are both embedded in social constructionism, which implies that individuals construct meaning through their continuous interactions with each other.

Based on the philosophical stance of interpretivism the study followed a qualitative research approach. The research design of the study was a phenomenological study. The data for the study was collected using semi-structured interviews. The researcher travelled the proposed tourism route to compile a preliminary list of the potential tourism role players/stakeholders (Refer to ). The list was updated during the main data gathering when the researcher travelled the route again and interviewed the participants. Interviews lasted on average 60 min, and was conducted at a location most convenient to the participants (i.e. in the product owner’s offices).

Data was collected from 33 participants, which included seven tourism officers, 14 tourism product owners, six product managers, one tourist guide, one Karoo Development Foundation (KDF) trustee, and four museum directors. The researcher utilised thematic content analysis to analyse the data. After the completion of the data gathering process, the researcher scrutinised the research notes and voice recordings of the interviews to identify common themes that emerged (Polkinghorne, Citation1995; Miller & Gatta, Citation2006; Maguire & Delahunt, Citation2017:3352). This allowed for an in-depth description of the phenomenon as seen through the eyes of people who have experienced it first-hand (Leedy & Ormrod, Citation2010:142).

The interview schedule consisted of four sections: Section A captured the demographics of the participants. Section B ascertained the perceptions of participants related to the infrastructure available on the proposed route, as well as the level of government involvement in tourism development in the area. Section C covered questions pertaining to whether the proposed route was viable, as well as the sites that should be included as part of the route. Participants were also probed on the potential impact of the route as well as suggestions on the establishment of a DMO. Section D required the participants to make recommendations towards the development of the South African War Battlefield Route for the central Karoo.

3. Findings

This section presents the findings of the empirical study. Sixteen participants were female and seventeen male. The majority (21) of the participants had a tertiary qualification, whilst eight of the participants completed secondary education. Four of the participants did not indicate their highest level of education.

It can be deduced from that the overall quality of the infrastructure in the central Karoo is in a good condition. This is supported by participant’s responses such as Participant 33:

The infrastructure in the region is in a good condition currently with certain maintenance taking place.

Table 1. Overall quality of the infrastructure in the region.

Table 2. South African War attractions in the region.

It is important to consider the level of involvement from government. Twenty participants identified that there is no involvement from government concerning tourism development in the region. Some of the quotations included concerning statements from participants such as the following:

We as product owners receive no help from government what so ever concerning tourism development in the region and they are up to no good. (Participant 12)

Tourism in the region is strongly private sector driven with no involvement from the government. (Participant 17)

There is not a lot of involvement from the government. (Participant 21)

Relatively good. (Participant 22)

No involvement from government, everything is privately run. (Participant 28)

Somewhat involved in the museum. (Participant 14)

I think the government is somewhat involved as the museums are currently in good condition. (Participant 18)

There is some involvement from the government, however they do not have the necessary funding to support tourism. (Participant 33)

The 4th Generation IDP 2017–2022 of the Beaufort West Municipality alludes to the opportunity provided by heritage tourism, and the opportunity for the Municipality to develop a plan that will promote local heritage to inform heritage tourism as well as underpin the Municipality’s focus on recreation (Beaufort West Municipality, Citation2017:21).

The Central Karoo District Municipality IDP 2017–2022 development objectives include establishing an inclusive tourism industry through sustainable development, and market which is public sector led, private sector driven and community based (Central Karoo District Municipality, Citation2017:104). It is thus clear that the above municipalities are working towards the inclusion of tourism/heritage tourism in their development plans.

shows participants felt that the establishment of a DMO was important. Most of the participants referred to the establishment of a forum to control the DMO. The participants felt that social media (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) could be one of the best platforms to market the route, as it is the most convenient and fastest way to market a tourism offering. Participants further indicated that print media must be utilised when marketing the route and should include magazines and a booklet with all the information on the route. Further, the notion that once the DMO was established, the route must be launched on local and international television shows (examples of shows included Kwela, Pasella, and Dark Tourist). The following section indicates some of the remarks from the participants concerning the guidelines of establishing a DMO:

Make sure the route has a strong online presence, and make sure that everybody works collaboratively towards the same goal. (Participant 5)

The proper research needs to be conducted so that it can be used by the DMO. (Participant 7)

We need to get this route marketed as wide as possible on television, exposure is key. (Participant 8)

Make use of magazines like Country Life to market the route in, and do not forget WOMF and social media presence. (Participant 17)

4. Discussion of findings

The following section provides a succinct discussion of the findings and its implications. According to Lourens (Citation2007:91) a challenge for route tourism is the provision of services and infrastructure. This notion is supported by Jovanović (Citation2016:288), who emphasised that tourism development depends on intensive investment in infrastructure. Infrastructure also needs to be continuously maintained and modernised. Numerous authors (see Lourens, Citation2007; Rogerson, Citation2007; Karim, Citation2011; Van der Merwe, Citation2014; Jovanovic, Citation2016:289; Hayes, Citation2018) emphasise the strong relationship between tourism development and infrastructure. Hattingh (Citation2016:157) highlights the importance of tourism infrastructure to ensure visitor satisfaction. The fact that the infrastructure of the central Karoo is well maintained is thus an advantage to the development of the proposed route. With the infrastructure in good overall standing, it thus leads to easy access to the relevant battlefield sites. Although the battlefield sites of this study mainly originated during the latter part (1901–1902) of the South African War, it plays an important role in the profiling of the war in this specific timeframe. It provides a good example of the guerrilla phase of the war in particular. The proposed route is thus a good example of Dark Tourism being made ‘alive’ by presenting tourists the opportunity of visiting these battlefield sites in the lesser-known Karoo. Participants in the study indicated that the overall condition of the attractions in the central Karoo is satisfactory. This research indicates thus that developing the South African War battlefields will add to the tourism offering of the central Karoo, growing it as a battlefields tourism node. However, the need for funding was reiterated, especially in the upkeep of attractions – a notion supported by the Tourism White Paper of South Africa (NDTRSA, Citation1996:10). According to Proos et al. (Citation2017:145), provincial governments should play an active role in tourism development and assist in tourism development by providing funding inter alia. However, the level of involvement from the government concerning tourism development seems to be a problem in the central Karoo. This correlates with Lourens (Citation2007:90), and Petrevska & Ackovska (Citation2015:80), that stated the issue of receiving support and funding from local government is still unresolved and limited.

The overall perspective of participants about the establishments of the South African War Battlefields Route in the central Karoo is one of positivity and interest. A large majority of participants stated that the tourism route would have a positive impact on the region. This correlates with similar findings on the positive impact of especially route tourism development in local areas (see Lourens, Citation2007). According to McLaren (Citation2011:262), strong leadership is required for a tourism route to flourish. Other aspects highlighted by the participants include co-operation and mutual support from all stakeholders involved in the development of the route, involvement from the community, and, good and sufficient infrastructure (McLaren, Citation2011; Nagy & Piskóti, Citation2016:84).

Guidelines for the establishment of a DMO included making extensive use of social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram etc.). Interesting to note that in 2011 McLaren (Citation2011:254) indicated that social media was not an important consideration in marketing tourism routes. This has however changed, and the use of social media in marketing has increased exponentially since 2011. McLaren (Citation2011:252) and Nagy & Piskóti (Citation2016:85), states that making use of electronic media are important as a marketing tool. This also emanated from the finding of this study. McLaren (Citation2011:256), also stated that the importance of Word of Mouth (WOM) in marketing a tourism route. The participants of the study also noted the importance of establishing a forum (or DMO) to manage and market the route and that the route should have a unique theme that can attract more visitors (Hattingh, Citation2016:158).

George (Citation2019:571) notes that promotion, building a brand identity, positioning the destination, portraying a image, providing information, improving international ties, organising workshops, trade shows and road shows, conducting research and packaging the destination are some of the major activities of a DMO. With reference to the participant’s responses to guidelines on the establishment of a DMO, the similarities were visible between what the participants reported as guidelines for the establishment of a DMO and the major activities of a DMO. These similarities include proper research about heritage, marketing routes at trade shows such as Indaba in South Africa, strong promotion (such as on TV, radio, social media etc.), hosting workshops with knowledgeable individuals, and packaging the destination under a strong brand name.

5. Conclusion

The development of tourism and especially tourism routes can contribute to the economic development of local areas. This especially applies to the central Karoo, a stark, spectacular area that offers unique heritage sites associated with the South African War. The main aim of the study was to investigate the potential for the development of the proposed route by involving potential stakeholders (specifically product owners and government officials) on the route. Participants indicated that the overall quality of the infrastructure in the central Karoo is in a good condition. Overall government commitment is lacking concerning tourism development. The most prominent themes that emerged from the findings included the importance of adequate management of the route, sufficient marketing of the route, and portraying the history of the various battles in the area.

In conclusion, the stakeholders in the central Karoo agree that there is a need to develop the South African War Battlefields Route, and that it could potentially assist in advancing heritage tourism in the central Karoo. Participants also felt that the establishment of a DMO was important. The study also briefly indicated that Dark Tourism can successfully be used as a means of attracting tourists. For future research, it is suggested that the demand-side perspective of tourists visiting the battlefields route can be measured.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Acha-Anyi, PN, 2018. Introduction to tourism planning & development igniting Africa’s tourism economy. Edited by PN. Acha-Anyi. Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

- Allen, D, 2015. Empire, war & cricket in South Africa. Zebra Press, Cape Town.

- Ashworth, GJ, 2004. Tourism and heritage of atrocity: Managaing the heritage of South African apartheid for entertainment. In TV Singh (Ed.), New horizons in tourism (pp. 95–108). Groningen: CABI Publishing.

- Atkinson, D, 2008. Towards “soft boundaries”: Pro-poor tourism and cross border collaboration in the arid areas of Southern Africa. http://www.aridareas.co.za/pdfdocuments/U3ATKINSONSoftBoundaries2008-02-20-led.pdf Accessed 5 February 2013.

- Atkinson, D, 2016a. Creating A Karoo battlefields heritage route project proposal and business plan, (January), 1–50.

- Atkinson, D, 2016b. Is South Africa’s great Karoo region becoming a tourism destination?. Journal of Arid Environments 127, 199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2015.12.006

- Beaufort West Municipality, 2017. 4th Generation inegrated development plan 2017–2022 Beaufort West Municipality. file:///C:/Users/eproos/Downloads/IDP 2017-2022 [Final Approved 30 June 2017] (1).pdf Accessed 16 September 2019.

- Beech, J, 2000. The enigma of holocaust sites as tourist attractions: The case of Buchenwald. Managing Leisure 5, 29–41. doi: 10.1080/136067100375722

- Boateng, H, Okoe, AF & Hinson, RE, 2018. Dark tourism: Exploring tourist’s experience at the Cape Coast Castle, Ghana. Tourism Management Perspectives 27(January), 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.05.004

- Breytenbach, J, 1977. Die Geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog in Suid-Afrika, 1899–1902: Deel IV. Pretoria: Die Staatsdrukker.

- Breytenbach, J, 1978. Die Geskiedenis van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog in Suid Afrika, 1899–1902 Deel 1 Die Boere Offensief Okt. - Nov. 1899. Die Staatsdrukker, Pretoria.

- Bryman, A, Bell, E, Hirschsohn, P, dos Santos, A, du Toit, J, Masenge, A, van Aardt, I & Wagner, C, 2014. Research methodology business and management contexts. Oxford University Press Southern Africa, Cape Town.

- Central Karoo, 2017. https://www.thegreatkaroo.com/listing/central_karoo Accessed 4 January 2018.

- Central Karoo District Municipality, 2017. Central Karoo district municipality IDP 2017–2022. https://www.skdm.co.za/sites/default/files/documents/Central Karoo Draft IDP 2017-22.pdf Accessed 20 September 2019.

- Central Karoo Information, no date. http://www.western-cape-info.com/provinces/region_info/6/Central Karoo Accessed 4 January 2018.

- Chang, LH, 2017. ‘Tourists’ perception of dark tourism and its impact on their emotional experience and geopolitical knowledge: A Comparative study of local and non-local tourist’. Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality 06(03), 1–5. doi: 10.4172/2324-8807.1000169

- Chowdhury, MF, 2014. Interpretivism in Aiding our understanding of the contemporary social world. Open Journal of Philosophy 4(4), 432–438. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp%5Cnhttp://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43047%5Cnhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. doi: 10.4236/ojpp.2014.43047

- Clarke, P & Eastgate, A, 2011. Cultural capital, life Course perspectives and western front battlefield tours. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 9(1), 31–44. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2010.527346

- Colesberg - Experience the Northern Cape, South Africa, 2019. https://www.experiencenortherncape.com/visitor/citiesandtowns/colesberg Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Constantine, RJ, 1996. The guerrille war in the Cape Colony: During the South African War of 1899–1902: A case study Of’ the republican and rebel commando movement. Dissertation, Cape Town, University of Cape Town.

- Dark Tourism: The Demand for new Experiences, 2017. https://www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4085490.html Accessed 23 November 2018.

- Domestic Tourism Growth Strategy 2012-2020, no date. https://www.tourism.gov.za/AboutNDT/Branches1/domestic/Documents/Domestic Tourism Growth Strategy 2012- 2020.pdf Accessed 21 August 2017.

- Dunkley, RA, 2007. The Thanatourist: Collected tales of the thanatourism experience. Doctor of Philosophy. Thesis, University of Wales.

- Dunkley, R, Morgan, N & Westwood, S, 2011. Visiting the trenches: Exploring meanings and motivations in battlefield tourism. Tourism Management. Elsevier Ltd 32(4), 860–868. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.07.0n doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.07.011

- Foley, M & Lennon, J, 1996. JFK and dark tourism: A fascination with Assassination. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2, 198–211. doi: 10.1080/13527259608722175

- George, R, 2019. Marketing tourism in South Africa. 6th edn. Oxford University Press Southern Africa, Cape Town.

- Google Maps, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/maps/@-31.755819,23.3618553,8.13z Accessed 23 July 2018.

- Grobler, J, 2018. Anglo-Boer War (South African War) 1899–1902. 30 South Publishers (Pty) Ltd, Pinetown. www.30degreessouth.co.za.

- Grobler, JE, 2017. The War reporter: The Anglo-Boer War through the eyes of the burghers. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Jeppestown.

- Ground Zero & the phenomena of ‘Dark Tourism’ - The Official Globe Trekker Website, no date. http://www.pilotguides.com/articles/ground-zero-the-phenomena-of-dark-tourism/ Accessed 6 December 2017.

- Hattingh, JL, 2016. The Karoo Riveria: A cross border tourism development plan For The Middle Orange River. Doctor of Business Administration. Thesis, Bloemfontein, Central University of Technology, Free State.

- Hattingh, JL, no date. Battlefields. The War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein.

- Hattingh, JL & Wessels, A, 2000. Britse Fortifikasies in die Anglo-Boereoorlog (1899–1902). The War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein.

- Hayes, K, 2018. Infrastructure and product development underpin tourism growth. http://www.tourismupdate.co.za/article/182453/Infrastructure-and-product-development-underpin-tourism-growth Accessed 9 January 2019.

- Historic Scotland (undated) Inventory of Historic Battlefields, 2009. http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/heritage/battlefields/battlefieldsunderconsideration.htm Accessed 29 March 2011.

- Holguin, S, 2005. “National Spain invites you”: Battlefield tourism during the Spanish Civil War. The American Historical Review 110, 1399–1426. doi: 10.1086/ahr.110.5.1399

- Jovanović, S, 2016. Infrastructure as important determinant of tourism development in the countries of Southeast Europe. Ecoforum 5(1), 288–294.

- Karim, I, 2011. Infrastructure is key to boosting tourism: The standard. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2000036644/infrastructure-is-key-to-boosting-tourism Accessed 9 January 2019.

- Karoo History Ganora Shelters, 2015. http://www.ganora.co.za/page/shelters Accessed 26 February 2018.

- Karoobattlefields, no date. Karoobattlefields. https://www.karoobattlefields.com/ Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Klein, C, 2016. Battle of Waterloo. http://www.history.com/news/7-things-you-may-not-know-about-the-battle-of-waterloo Accessed 8 August 2016.

- Kruger, C (ed.), 1999. Die wat, waar en wanneer van die Boer se stryd. FAK, Cape Town.

- Leedy, PD & Ormrod, JE, 2010. Practical research planning and design. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Merill, New Jersey.

- Lennon, J & Foley, M, 2000. Dark tourism: The atraction of death and disaster. Continuum, London.

- Light, D, 2017. Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism. Tourism Management 61, 275–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.011

- Lourens, M, 2007. Route tourism: A roadmap for successful destinations and local economic development. Development Southern Africa 24(3), 475–490. doi: 10.1080/03768350701445574

- Maguire, M & Delahunt, B, 2017. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. Aishe-J 3(3), 3351–33514.

- Marais, C, 2017. Tombstone travel in the Karoo. Country Life February, 38–43.

- Maree, K, 2016. First steps in research. 2nd ed. Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

- Maurice, F, 1906. History of the War in South Africa 1899–1902. Hurts and Blackett Limited, London.

- McLaren, L, 2011. Critical marketing success factors for sustainable rural tourism routes : A Kwazulu-Natal stakeholder perspective. Dissertation, Pretoria, University of Pretoria.

- Miles, S, 2014. Battlefield sites as dark tourism attractions: An analysis of experience. Journal of Heritage Tourism 9(2), 134–147. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2013.871017

- Miles, ST, 2012. Battlefield tourism: Meanings and interpretations. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3547/1/2012milesphd22.pdf.

- Miller, S & Gatta, J, 2006. The use of mixed methods models and designs in the human sciences: Problems and prospects, quality & quantity. Quality and Quantity 40(4), 595–610. doi: 10.1007/s11135-005-1099-0

- Misztal, B, 2003. Theories of social remembering. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Moeller, M, 2005. Battlefield tourism in South Africa with special reference to Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift KwaZulu-Natal. Dissertation, Pretoria, University of Pretoria.

- Nagy, K & Piskóti, I, 2016. Route-based tourism product development as a tool for social innovation: History valley in the cserehát region. Theory, Methodology, Practice 12(SI), 75–86.

- National Department of Tourism Republic of South Africa (NDTRSA), 1996. White paper the development and promotion of tourism in South Africa. Cape Town. http://scnc.ukzn.ac.za/doc/tourism/White_Paper.htm.

- National Department of Tourism Republic of South Africa (NDTRSA), 2012. National heritage and cultural tourism strategy. https://www.tourism.gov.za/AboutNDT/Branches1/domestic/Documents/National Heritage and Cultural Tourism Strategy.pdf Accessed 18 January 2018.

- Nothling, CJ (ed.), 1998. South African military yearbook 1998. South African Military Consultants, Pretoria.

- Pakenham, T, 1979. The Boer War. 1st edn. Futura Publications, London.

- Petrevska, B & Ackovska, M, 2015. Tourism development in Macedonia: Evaluation of the Wine route region. Ekonomika 61(3), 73–83. doi: 10.5937/ekonomika1503073P

- Pixley Ka Seme Municipality, 2017. Pixley Ka Seme municipality integrated development plan 2017–2022. http://www.pksdm.gov.za/idps/PIX IDP 2017-2022 Final 11 June 17.pdf Accessed 16 September 2019.

- Podoshen, JS, 2013. Dark tourism motivations: Simulation, emotional contagion and topographic comparison. Tourism Management. Elsevier Ltd 35, 263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.08.002

- Polkinghorne, DE, 1995. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 8(1), 5–23. doi: 10.1080/0951839950080103

- Pretorius, F, 1998. Die Anglo-Boereoorlog 1899–1902. Struik Uitgewers, Cape Town.

- Project, KB, no date. Karoo Battlefields project. https://www.karoofoundation.co.za/karoobattlefields.html Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Proos, E, Kokt, D & Hattingh, JL, 2017. Marketing and management effectiveness of free state section of maloti Drakensberg route. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 39(1), 135–147.

- Reitz, D, 1929. Kommando n Boere Dagboek uit die Engelse Oorlog. A.C. WHITE D. & U. KIE, BPK. whiteco huis, Bloemfontein.

- Rogerson, CM, 2007. Tourism routes as vehicles for local economic development in South Africa: The example of the Magaliesberg Meander. Urban Forum 18, 49–68. doi: 10.1007/s12132-007-9006-5

- Rojek, C, 1993. Way of seeing modern transformation in leisure and travel. Macmillan, London.

- Ryan, C, 2007. Battlefield tourism: History, place and interpretation. Elsevier Ltd, Amsterdam.

- Schoeman, C, 2013a. Churchill’s South Africa travels during the Anglo-Boer War. Zebra Press, Cape Town.

- Schoeman, C, 2013b. The historical Karoo traces of the past in South Africa’s arid interior. Edited by B. Leak. Zebra P-ress, Cape Town.

- Scholtz, GD, 2000. The Anglo-Boer War 1899–1902. 1st edn. Protea Book House, Menlo Park.

- Seaton, A, 1996. Guided by the dark: From thanatopis to thanatourism. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2(4), 234–244. doi: 10.1080/13527259608722178

- Seaton, A, 1999. War and Thanatourism. Waterloo 1815–1914. Annals of Tourism Research. http://sciencedirect.com/ Accessed 12 August 2004.

- Seaton, A, 2000. “Another weekend away looking for dead bodies … ”: Battlefield tourism on the somme and in Flanders. Tourism Recreation Research 25(3), 63–77. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2000.11014926

- Sekaran, U & Bougie, R, 2016. Research methods for Business. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, West Sussex.

- Sharpley, R & Stone, PR, 2009. The darker side of travel. Chanel View Publications, Bristol.

- Smith, V, 1998. War and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 25(1), 202–227. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00086-8

- South African Tourism (SAT), no date. South African tourism. https://www.southafrica.net/gl/en/corporate Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Special Interest Tourism, 2016. http://www.acsedu.co.uk/Info/Hospitality-and-Tourism/Tourism/Special-Interest-Tourism.aspx Accessed 12 October 2016.

- Stone, PR, 2006. A dark tourism spectrum : Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/selectedworks-dr-philip-stone-2006-dark-tourism-spectrum-towards-typology-death-macabre-related-tour/.

- Stone, P & Sharpley, R, 2008. Consuming dark tourism: A thanatological perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 35(2), 574–595. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.003

- The magical Great Karoo, 2017. http://www.southafrica.net/za/en/articles/entry/article-southafrica.net-the-magical-great-karoo Accessed 7 July 2017.

- Van den Berg, G, 1998. Die oorlog aan die Wesfront en in Wes-Transvaal. In C Nothling (Ed.), South African military yearbook 1998. South African Military Consultants, Pretoria, pp. 10–37.

- Van der Merwe, CD, 2014. Battlefields tourism: The status of heritage tourism in Dundee, South Africa. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 26(26), 121–139. doi: 10.2478/bog-2014-0049

- Van der Merwe, CD, 2019. Battlefield tourism at Magersfontein: The case of heritage tourism in the Northern Cape, South Africa. In Contemporary military geosciences. Stellenboch: Sun Press, pp. 25–49.

- Van Dyk, A, 2017. Interview with Dr Arnold van Dyk. Bloemfontein.

- Van Zyl, J, Constantine, R & Pretorius, T, 2012. An Illustrated history of black South Africans in the Anglo-Boer War 1899–1902 - A forgotten history. Edited by R. Constantine. The War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein.

- Venter, D, 2011. Battlefield tourism in the South African context. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 1(3), 1–5.

- Von der Heyde, N, 2013. Field guide to the battlefields of South Africa. Edited by C. Dos Santos. Struik Travel & Heritage, Cape Town.

- Von der Heyde, N, 2017. Guide to sieges of South Africa. Edited by R. Theron and E. Bowles. Struik Travel & Heritage, Cape Town.

- Walliman, N, 2016. In M Steele (Ed.), Social research methods. 2nd ed. SAGE Publications Ltd, London.

- Wessels, A, 1991. Die Anglo-Boereoorlog 1899–1902. Oorlogsmuseum van die Boererepublieke, Bloemfontein.

- Willis, R, 1998. Anglo-Boer War tourist routes of the Great Karoo. In C Nothling (Ed.), South African military yearbook 1998. South African Military Consultants, Pretoria, pp. 48–60.

- Winter, C, 2012. Commemoration of the Great War on the Somme: Exploring Personal Connections. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 10(3), 248–263. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2012.694450