ABSTRACT

Impact investing is making important and positive contributions to the socio-economic development of groups at the bottom-of-the-pyramid. Independent literature streams reveal how in resource scarce contexts of sub-Saharan Africa, businesses are increasingly tapping into this emerging opportunity which is extending loans and other forms of capital. However, to date, there is very limited understanding of this domain from a hospitality and tourism perspective. By synthesising across these literature streams, we explore the opportunities, constraints and nature of impact investing, and theorise its key determinants in resource scarce contexts. In order to elaborate our theorisation, we content analyse published accounts, namely industry reports and academic literature, to argue for the need for more impact investing in hospitality and tourism, a sector that has traditionally suffered from under-financing and limited politico-economic recognition. The study lays a foundation for future research in impact investing in hospitality and tourism and yields important policy and managerial implications.

1. Introduction

This study critically analyses and explores how hospitality and tourism (H&T) enterprises in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) can leverage funds from impact investing (i-investing or II) by examining the nature of II and its potential contribution to the development and growth of small and medium tourism firms (STFs).Footnote1 By ‘providing a wide range of tourism and hospitality services’ (Zhao et al., Citation2011:1573), STFs include transport, food and beverage (F&B), accommodation providers and ancillary services (Bosworth & Farrell, Citation2011:1479) and play a very important role in promoting tourism entrepreneurship in developing countries. However, the lack of capital (finance and non-financial support), limited management skills and capabilities and good governance mechanisms seriously hinder their ability to actively contribute to local social and economic development (see e.g. Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2013; Kimbu et al., Citation2019; Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Tichaawa & Kimbu, Citation2019). This is where II could play an important role.

Impact investing is defined as ‘socially responsible investing that produces triple bottom line results’ (Brest & Borne, Citation2013b). It is an investment opportunity (Hope Consulting, Citation2010) and/or an investment approach (World Economic Forum [WEF], Citation2013) made by investors into companies, organisations and funds with clear intentions to create measurable financial, social and environmental impacts alongside a financial return for the investors, regardless of stage of maturity of the beneficiary enterprises (see e.g. Castellas & Ormiston, Citation2018; Choda & Taladia, Citation2018; Urban & George, Citation2018; Agrawal & Hockerts, Citation2019; Findlay & Moran, Citation2019; Mogapi et al., Citation2019; Roundy, Citation2019; Tekula & Anderson, Citation2019). They are therefore ‘investments intended to create positive impact beyond financial return’ (O’Donohoe et al., Citation2010:5; Roundy et al., Citation2017; Lehner et al., Citation2018). II is therefore not only about seeking to avoid investing in companies that do harm, but it crucially involves ‘actively placing capital in enterprises [mostly in developing low income countries] that generate social and/or environmental goods, services, or ancillary benefits [e.g. creating jobs, improving healthcare, infrastructural development], with a range of expected returns … to the investor’ (The Parthenon Group and Bridges Ventures, Citation2010:3). II has witnessed steady growth within the last two decades because of a growing number of investors expressing a desire to ‘do good while doing well’. These are known as impact investors (i-investors) as they seek to ‘ … integrate social, ethical and/or corporate governance concerns in the investment process’ (Sandberg et al., Citation2009:521). i-investors thus create ‘opportunities for financial investments that produce significant social or environmental benefits’ for all parties concerned, that would otherwise not occur but for their investment in a social enterprise (Brest & Born, Citation2013a).

Bugg-Levine & Goldstein (Citation2011) and Koh et al. (Citation2012) note that the creation of inclusive businesses targeting bottom-of-the-pyramid (BoP) entrepreneurs and markets with a focus on marginalised groups, in addition to the importance of improving access to essential goods and services for the poor primarily in emerging markets, is a key feature of II (Dolan, Citation2012). This is a viewpoint supported by large i-investors (e.g. Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN); Rockefeller Foundation) and multi-lateral development finance institutions (e.g. the World Bank), all of whom are very supportive of the growing II movement, and presently produce most of its literature. With about $10.6 billion in impact investments made in 2013 alone, and growing rapidly, the GIIN estimates from its survey data that there are now $228 billion in II assets, which is roughly double that of 2017 (Dallmann, Citation2018). II proponents are optimistic that it can be a real panacea for poverty alleviation, environmental protection, social and economic development in SSA, Asia and Latin America as noted by WEF (Citation2014). Within the next decade, SSA is the region where these i-investors are planning to increase their allocations the most (Saldinger, Citation2014), and mainly in enterprises that actively seek positive social and environmental benefits in addition to profit.

However, in spite of its increasing recognition and acceptance, coupled with the growth of research and literature dealing with II in sectors such as microfinance (Bauchet et al., Citation2011; CGAP, Citation2013; Rozas et al., Citation2014), agriculture (GIIN, Citation2011; Citation2012, Citation2016), housing and education (CDC, Citation2014; DFID, Citation2014), as well as renewable energies and sustainable manufacturing (Staub-Bisang, Citation2012) in Africa, Asia and Latin America within the last two decades, there is a dearth of research dealing with II in other sectors such as H&T. This is notwithstanding the fact that H&T is nowadays widely accepted and recognised as one of the world’s fastest growing economic sectors, contributing about 10% to global gross domestic product (GDP), and a key driver for poverty alleviation, socio-economic progress and development in many emerging SSA destinations (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2013; World Travel & Tourism Council [WTTC] Citation2019). Given such importance, it is therefore imperative to undertake research geared towards understanding and unpacking the potential of II in the H&T industry especially in SSA countries, focusing on small tourism firms (STFs), which make up the bulk of businesses operating in this sector and at the BoP.

Our main objective is therefore to articulate the determinants of II and the multiple ways in which II can stimulate and contribute to tourism development in SSA via support to small and medium tourism firms. By unpacking this multiplicity, we develop stylised facts and predictive propositions pertaining to the role of II in SSA, focusing on value chains, goals, intentionality nature and potential benefits of II for STFs. Thus, we contribute an H&T perspective to the management literature debating how II can support non-traditional sectors such as STFs in emerging economies to deal with capital and organisational constraints, by using their capabilities and resources to advance the creation/growth of inclusive STFs and entrepreneurs among BoP and marginalised communities spurring inclusive growth and socio-economic development (Bugg-Levine & Goldstein, Citation2011). Our findings deepen recent debates about the effectiveness of II as a tool for inclusion, especially considering its current focus on traditional sectors such as agriculture, finance, healthcare and education whilst ignoring non-traditional sectors as H&T.

We begin by reviewing three literature streams, the role of STFs in the tourism value chain, the key characteristics of II, the nature of impact, the investors and their investments, and the benefits of II. The review enables us to demonstrate that a better understanding of the II landscape is necessary by STFs in SSA if they are to succeed in attracting impact funds. Next, we synthesise across the literature streams to develop a theoretical framework depicting the determinants of II on the STF value chain. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of our framework for i-investors and beneficiaries of impact funds in H&T, along with an agenda for future research.

2. Background literature

2.1. STFs in the tourism value chain

Value chains in tourism reflect the fact that tourism is a networked and complex industry which is information intensive, highly susceptible to digital delivery, and targeted towards customers who are typically not locals. This makes tourism to have multiple entries into the value chains, which is unlike what may exist in other industries where the linear model of production is often the norm. Recent advances in information and communication technologies (ICTs) have placed the consumer at the centre of the chain enabling rapid communication with end users and customers anywhere along the value chain (Park et al., Citation2015). This provides a good opportunity for tourism small and medium enterprises (SMEs)/STFs, with their small size and flexibility, to play important roles in enhancing customer satisfaction, individualised treatment and capital generation, which can be done through sourcing for impact funds.

A WEF (Citation2013) report suggests that mainstream private investors (e.g. asset owners and asset managers) offer the biggest opportunity to scale-up the II sector as they complement philanthropic approaches to solving the most pressing social problems through funding and technical assistance ‘to improve society’ at the BoP. This approach, it is believed, drives investor commitment and competitive advantage for i-investors in return. According to Koh et al. (Citation2012) and Freireich & Fulton (Citation2009:15), a market-based approach imposes major constraints on the creation of inclusive businesses due to incompatibility with the challenging reality on the ground in developing countries, such as the lack of efficient intermediation, enabling infrastructure and sufficient absorptive capacity for capital. The situation is even worse in non-traditional sectors such as H&T (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016; Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2016). Koh et al. (Citation2012) further note that ‘more, not less, philanthropy’ applied in ‘new ways’ is needed to complement market-based impact capital in dealing with the extreme challenges facing ‘inclusive business pioneers’. Even though there is agreement that both market-based and philanthropy approaches are here to stay, there is a need to find ‘new ways’ to make them complement each other to better achieve the goal of creating inclusive businesses in Africa in both traditional and non-traditional sectors.

From a supply side perspective, every II organisation has a business model. A business model in this context depicts how a specific II initiative is conceptualised to deliver pre-stated objectives as well as capture any value created through its implementation (evaluations) (The The Rockefeller Foundation, Citation2012). There are also II business models developed as analytical frameworks to describe different types of II business models. For example, the WEF (Citation2013) report defines an II business model in terms of risks (high, medium and low), availability of capital, and scope for scaling-up impacts at the firm level. Another model proposed by Omidyar Network (Bannick & Goldman, Citation2012) goes beyond the level of an individual firm (firm-level effects) to include different types of capital aimed at scaling-up whole industry sectors (sector-level effects). The notion of inclusive businesses thus requires an emphasis on both firm-level and sector-level.

From a demand side perspective, even though many impact enterprises in developing countries have their own business models, built-in mechanisms to measure and monitor progress, sustain success in achieving stated objectives are often lacking. Their impacts are therefore not often quantifiable in the long term. This is especially serious in H&T (in SSA) where the majority of businesses are micro, small and medium businesses, with the owners having limited relevant expertise and management skills (Kimbu et al., Citation2019). Various studies (e.g. Dalberg, Citation2011, Citation2012; Fletcher, Citation2011; Dolan, Citation2012) suggest that consciously seeking to create a direct scalable social impact through their business models can enable impact enterprises in Africa to better serve as engines of wealth creation and economic growth and to better support general micro, small and medium size enterprise (MSME) activity. This makes impact enterprises different from ordinary businesses in that their business models seek to tackle social issues at scale through local content (e.g. supply/distribution chains and employment of marginalised groups), provide access to the ‘much needed goods and services to low-income groups in a financially sustainable and scalable way’, and sustainable management of natural resources (Dalberg, Citation2012:3). The above-mentioned studies also call for more research to better understand the challenges facing impact enterprises in a country. Other similar reports on Africa (e.g. Dalberg, Citation2011; GIIN, Citation2011; Huppe & Silva, Citation2013) also suggest the need for more empirical research to identify and help promote the case for supporting impact enterprises in dealing with both supply-side and demand-side challenges, which is what this study aims to do using the case of STFs in SSA destinations such as Cameroon.

Proposition 1: Contextualizing impact investing in H&T requires an in depth understanding of the tourism value chain i.e. both the supply side requirements and the demand side conditions, which are characterised by different contextual factors likely to enable the uptake or not of II initiatives that will generate expected impacts.

2.2. Characteristics of impact investing

One strand of literature examines the core characteristics of II evidencing two main characteristics, namely subjectivity of goals and intentionality, while another strand of literature focuses on the nature of the impact and its benefits while yet another focuses on the nature of investors and their investments. These are all critically discussed and analysed hereafter. These aspects of II provide a critical background to the review that informed our definition of II in resource scarce contexts. For this we searched a combination of three key words/phrases, namely ‘II’, ‘II in tourism and/or hospitality’, ‘resource scarce context’ and ‘II in Africa’, in four databases, namely ScienceDirect, Sage Journals, Taylor & Francis Online and Emerald Insights (e.g. Jin et al., Citation2017). Further searches were carried out in Google Scholar and the university library databases of the two authors. We undertook a critical review of the literature to isolate those articles that included a mention of the above words/phrases. presents a summary of the key literature on II. While illuminates II as an emerging research theme, three key observations could be made. Firstly, we determined that over the last few years, the scope of the research has mainly been conducted in the resourceful Global North context. Secondly, in terms of Africa, very limited empirical research has been done on II, with most of the literature dominated by commissioned reports by the GIIN and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Thirdly, and most significantly, there is no focus on the H&T sector in general and in Africa in particular despite its significance, as previously highlighted in this paper. These factors therefore justify the need to steamroll the debates about and research on II in H&T.

Table 1. Some key literature on impact investing (II).

2.2.1. Subjectivity of goals and intentionality

The goals and objectives of i-investors are often quite comprehensive and varied as the range of those often encountered in traditional philanthropy, and sometimes compete and contradicting with those of other investors (Brest & Born, Citation2013a). Depending on the investors, these goals often range, for example, from promoting community development and empowerment of women and other under-privileged groups in urban and rural areas, through micro and small business enterprise development and microfinance provision, to vocational education and training opportunities, energy efficiency projects and low-cost health initiatives which produce positive social value (Dalberg, Citation2012). The choice of objectives and projects to invest in are subjective and from a moral/philosophical point of view, some tend to produce negative social value. Consequently, some goals/projects might be considered as more valuable and having more positive impact than others depending on the perspective of the individual (Friedman, Citation2013). However, ‘whether an activity has impact in achieving a specified goal is essentially a technical, value-neutral question’ (Brest & Born, Citation2013a).

Relatedly, unlike ‘socially neutral’ investors, who are indifferent to the social consequences of their investments and make investment decisions based solely on expected financial returns (Brest & Born, Citation2013b), i-investors are by nature socially motivated individuals/organisations or groups of individuals/organisations whose main intention is to achieve social and/or environmental goals through their investments while at the same time making a profit or not losing the seed capital (Fletcher, Citation2011; Brest & Born, Citation2014). These goals vary in content and context and are often spatio-temporarily determined. They range, for example, from providing specific tailored solutions to particular problems faced by groups of individuals/communities in developing countries to solving general problems dealing with humanity irrespective of location (Brest & Harvey, Citation2008).

However, because each investor’s motivation(s) and goal(s) is/are likely going to be different from that of the other investors, each investor’s goals will likely be considered as being socially neutral by the other investors in respect to their own investments as they might not share the same intentions/goals. Consequently, all investors at one stage or another could be considered as being socially and environmentally neutral. This notwithstanding, there is a growing body of research (e.g. Freireich & Fulton, Citation2009; Koh et al., Citation2012; Brest & Born, Citation2013a; Scholtens, Citation2014) which identifies and analyses some of the key defining characteristics and value of ‘socially conscious’ investors and investments, emphasises bottom-up development, and supports BoP market building initiatives/investments as having long-term economic, social and environmental impacts in contrast to ‘socially neutral’ investments which aim to maximise financial returns to the investors.

Proposition 2: i-investors are socially conscious investors who emphasize bottom-up development and support BoP market building initiatives/investments that have long-term economic, social and environmental impacts.

2.2.2. The nature of impact and benefits of impact investing

Another strand of the literature focuses on the nature of the impact and its benefits. Understanding what would have happened if a particular investment or activity had not occurred requires an examination of the following three key elements (parameters) which are central in appraising the nature of impact investments. These are: ‘(1) the impact of the enterprise itself, (2) investors’ contribution to the enterprise’s impact, and (3) the contribution of nonmonetary activities to the enterprise’s impact’ (Brest & Born, Citation2013a) on its stakeholders both within and out of the firm from a financial, social and environmental perspective. Worthy of note is the fact that proof of additionality Footnote2 must be evident before an investment or non-monetary activity can be deemed to have any impact. With regard to enterprise impact, Brest & Born (Citation2013b) note that i-investors’ impacts together with those of other stakeholders/actors fundamentally depend on the impact of the enterprises they support. There are several ways in which an enterprise’s impact can be felt/manifested but it is most visible and felt from a product and operational perspective. Product impacts refer to the impacts generated from the goods or services manufactured and provided by an enterprise (e.g. ecofriendly holiday packages, constructing environmentally friendly hotels, fuel efficient airplanes). Operational impacts, on the other hand, are the impacts of the enterprise’s management practices on what ‘are often described as environmental, social, and governance (ESG)’ of corporate social responsibility (CSR) factors. According to Olsen & Galimidi (Citation2008), these are the enterprise’s impacts on its employees’ social, economic and environmental security, and other aspects of the community’s wellbeing within which an enterprise operates. It also covers the environmental effects of an enterprise’s supply chain and its operations.

It is worth noting that collaboration between enterprises, if pursued, often leads to an increase or multiplication of product (scaling up) or operational impacts, resulting in the industry benefitting from collective impacts which result from the commitment of businesses to work together with other important actors such as not-for-profit and non-governmental organisations, foundations and government agencies, to tackle specific social problems within the community (such as prostitution, child labour, drug abuse, low wages and long working hours) in some tourist destinations (Kania & Kramer, Citation2011). Sector impact relates to an enterprise’s impact on the markets and sectors in which it operates beyond its particular mission. This is only evident and likely in enterprises which have product and operational impacts. A hospitality/restaurant business which, for example, decides to introduce the use of only locally sourced and environmentally friendly fair-trade products in its hotels/restaurants may develop and set quality standards in its value chain as well as train its suppliers and partners in their compliance and application, leading to increased technical, organisational and personal value. If commercially successful, the spillover effects for other similar businesses in the region will be positive as it would attract other eager entrants and foster the development of new businesses.

One of the main benefits of II to an enterprise is additionality. Additionality occurs when an investment increases the quantity or quality of the enterprise’s social output beyond what would otherwise have occurred. It is worth noting that additionality is a key factor necessary for an investment to have an impact. These impacts are manifested in capital benefits for the beneficiary enterprise through: Price (i.e. below market investments), Pledge (on loan guarantees), Position (through subordinated debt or equity positions), Patience (guaranteeing longer terms before exiting), Purpose (enabling flexibility in adapting capital investments to the enterprise’s needs) and Perspicacity (through foresight in discerning opportunities that ordinary investors do not see) (Schwartz, as cited in Brest & Born, Citation2013a).

Proposition 3: The capital benefits from II enable enterprises to achieve market returns, scale up and experiment while pursuing their social objectives.

2.2.3. The Nature of investors and their investments

Impact investors may be qualified as socially motivated-concessionary or non-concessionary investors interested in identifying and capitalising on opportunities that bring benefits to them and to society. They are often referred to as ‘financial first’ and ‘impact first’ investors, whose business orientation is geared towards achieving the ‘double bottom line’ respectively (Freireich & Fulton, Citation2009; WEF, Citation2013; Ormiston et al., Citation2015). In order to achieve expected social benefits and have real impact, concessionary investors are prepared to and do make sacrifices to achieve their social goals, especially in the form of free expert advice, and/or financial support, often in the form of charitable donations or grants when setting up or expanding the enterprise. There is often little expectation of any form of financial returns or remuneration at the very beginning or in the short term as these are sacrificed by the investors in return for social benefits (GIIN, Citation2013; Johnson & Lee, Citation2013). By supporting nascent enterprises, for example, through making available the necessary (start-up or expansion) financial and human capital, and expert technological and marketing skills/know-how which these enterprises would otherwise not be able to access, as is often the case with many small tourism firms (e.g. Ngoasong & Kimbu, 2016), a concessionary investor’s investments impact is felt almost from the very onset. Although this involves a higher risk for the i-investor and/or lower returns on investments (ROI) (WEF, Citation2013), the impacts on society are far greater, especially when dealing with BoP populations, to which a good proportion of STFs owners/managers in SSA belong.

The unwillingness to make any financial sacrifice to achieve social goals is a key trait of non-concessionary investors. Their impact is mostly felt in niche and/or under-appreciated markets (e.g. social and environmentally friendly and nature tourism ventures) where access to information is difficult (Johnson & Lee, Citation2013). Consequently, only they or their intermediaries have access to intelligence and/or special expertise on the ground enabling them to have a competitive edge over other potential investors/competitors. Their actions on these niche markets thus have positive impacts on the communities, while at the same time enabling the investors to make a profit from their investments. They are willing and ready to take risks and bear extra costs while investing in these niche (hospitality and tourism) markets and businesses in emerging destinations of developing countries which ordinary investors would likely be unwilling to undertake (Brest & Born, Citation2013b).

Proposition 4: In order to achieve expected financial and social benefits and have real impact, i-investors should be prepared to make financial and non-financial sacrifices to achieve their social goals when setting up or expanding the (H&T) enterprise.

3. Determinants of impact investing for tourism development: A theoretical framework

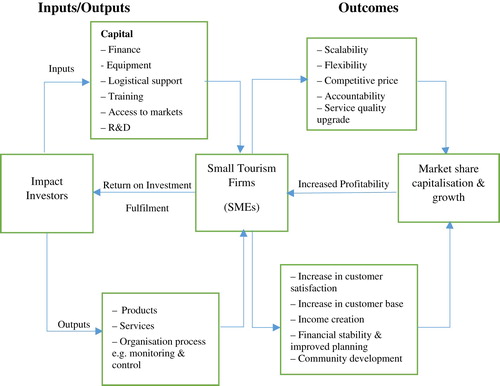

Our synthesis across the literature streams is scaffolded on the theoretical framework defined in , which integrates narrowly defined frameworks in existing studies relating to the determinants of II, the nature of the impact and its expected outputs and outcomes, namely resource acquisition and investments in businesses with the goal of creating measurable social change and returns on the investments of the investors. Thus, we refine existing frameworks in three critical ways, namely inputs, outputs and outcomes. Making a clear distinction between inputs, outputs and outcomes is very important in discussing and assessing the impact of II in (H&T) enterprises.

Figure 1. Understanding the determinants of impact investing (II) for tourism development. Source: Authors conceptualisation drawing on Dalberg (Citation2012), Fletcher (Citation2011), Dalberg (Citation2011, Citation2012), Brest & Born (Citation2014).

Note: R&D: research and development; SMEs: small and medium enterprises (small tourism firms).

A keen contextual understanding of the tourism value chain by i-investors (Proposition 1) will enable targeted capital investments, namely inputs (e.g. finance and equipment, service delivery and management training, and logistical support) into, for example, women-owned small and medium hotels, F&B businesses, and/or targeted training and employment opportunities to marginalised groups such as women and youth employed in tourism, therefore impacting on the quality of products and services (outputs) delivered by tourism SMEs. Tourism SMEs will be able to scale production, enhance service and product quality, and strengthen accountability, ultimately leading to an increased customer base and satisfaction, financial stability via increased return on investment for the firm and the investors (Proposition 3), and ultimately improving the targeted community’s wellbeing and overall societal development (outcomes). These three factors should be of prime importance to any potential H&T i-investor and II beneficiary.

Before (considering) investing in a tourism enterprise, it is imperative that the i-investor fully considers the extent to which the intended capital inputs and outputs will generate expected outcomes (from a product or operational perspective). The extent (scale) to which this output will contribute to the intended outcome (e.g. personal and community development, women empowerment through tourism entrepreneurship, training/employment of minorities) (Dalberg, Citation2012; WEF, Citation2013) and/or if it would still have occurred anyway without i-investments in the new output should also be considered (Proposition 2). Additionally, thought should also be given to how this will be documented. This approach, when effectively undertaken, would lead to socially responsible II in H&T as it will generate ‘ … exceptional social impact and a financial return … in enterprises that benefit the poor … ’ through the adoption of clear standards and documentary evidence (McCreless & Trelstad, Citation2012:22), an issue which extant research has highlighted as lacking in many STFs operating in Africa (e.g. Ngoasong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Ngoasong & Kimbu 2016; Kimbu & Ngoasong, 2016).

However, measuring/evaluating impact investment performance is expensive and not always easy as it requires measuring both financial and social returns. This is often difficult as it requires serious resource commitment (Proposition 4) from the i-investors, and good quality data, which is often difficult to come by in emerging tourism destinations of Africa and the global south (Kimbu, Citation2011; Johnson & Lee, Citation2013). Consequently, II measurement is typically funded by private foundations and international development institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) who prefer to fund, monitor and evaluate i-investments in mainstream industries using standardised metrics such as the Impact Reporting and Investment Standards (IRIS) and the Global Impact Investment Rating System (GIIRS). These two tools (which are continuously being refined) have been specially developed for assessing and rating an enterprise’s social or environmental performance and have gained traction amongst major impact investors and industry stakeholders (The The Rockefeller Foundation, Citation2012). However, their main weakness lies in their inability to measure the social value of the actions of i-investors. This is because financial and operational measures lie at the heart of the IRIS framework, while GIIRS ratings are survey-based, covering five categories: leadership, employees, environment, and community (operations oriented) and products and services (output oriented). This limits their ability to measure non-quantifiable variables (The Rockefeller Foundation, Citation2012; Johnson & Lee, Citation2013). Measuring the social value of II could be even more challenging for H&T businesses, which in Africa are often family-owned and -managed, with no clearly defined boundaries between business capital and personal finance, and most of the start-up and expansion capital together, with labour being provided by family and kin (Ngoasong & Kimbu, 2016).

4. Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we explain the role of small tourism firms in the tourism value chain, the main characteristics of II, and we develop propositions which i-investors would have to realign with when dealing with businesses in H&T. Ngoasong & Kimbu (2016:431) posit that ‘development-led tourism entrepreneurship is a process where small private firms and local communities are encouraged and supported to use tourism to promote local development and vice versa’. i-investors pursue a similar empowerment logic, providing loans, technical capacity and development opportunities that facilitate the creation and scaling-up of businesses that contribute to inclusive BoP development while making a return on their investment (Agrawal & Hockerts, Citation2019; Tekula & Anderson, Citation2019). Propositions 1 and 2 suggest the need for an in-depth understanding of the tourism value chain and its contextual specificities in SSA by impact investors, as the success or failure of their goal of emphasising BoP development by supporting BoP market building initiatives/investments with long-term economic, social and environmental impacts is dependent upon this. For example, unlike duration-specific IMF-/World Bank-funded state-run initiatives geared towards tourism development in the 1980s and 1990s, most of which did not succeed (Kwaramba et al., Citation2012; Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2013), i-investors can capitalise on the recent prioritisation of tourism development in many African countries (manifested via the loosening of travel/visa restrictions, business- and tourism-friendly policy initiatives, and other infrastructural developments) to support inclusion and local development through tourism in SSA countries by providing much-needed funding, business training and marketing support needed by STFs to be competitive, and socially and environmentally sustainable (Kimbu et al., Citation2019). i-investors can also be crucial in complementing the limited state funding and tourism development initiatives, as well as STFs’ inability to secure credit from commercial banks, which has been identified as seriously impacting the growth of STFs (Ngoasong & Kimbu, 2016). For this to be possible, II organisations would have to reduce their loan thresholds, which are most often higher than the amounts required by many STFs to start or grow their businesses (Ngoasong et al., Citation2015). Alternatively, they could consider developing tailored packages for H&T businesses, taking into consideration the specificities of the sector.

Our Propositions 3 and 4 suggest that II enables enterprises to achieve market returns, scale up and experiment while pursuing their social and environmental objectives, but to achieve this they should be prepared to make financial and non-financial sacrifices especially within the context of tourism. This combination of a development and banking logic (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010:1419) can enable II organisations to provide direct and indirect support to development-oriented STFs at the BoP. Direct support, as Ngoasong & Kimbu (2016:431) indicate, may ‘include funding for creating [and/or scaling-up] STFs that in turn serve the tourism industry value chain’, while indirect support can be in the form of muchneeded skills, capacity and capability development of the entrepreneurs. This has been observed to represent a serious drawback to the success of many STFs in Africa, but which, if well planned and developed, would lead to business expansion, improvement in service quality customer/visitor satisfaction and BoP development.

Every investment is an ‘impact investment’ (be it economic/financial, environmental and/or social) either intentionally or unintentionally. Just as in ordinary life and business where targets and goal-setting are important determinants that enable the measurement and assessment of success, intentionality (of the investor) in II is very important because it enables the measurement of results, as well as an assessment of the impacts of an investment in relation to the particular goal the investment set out to achieve. This paper provides an important starting point to initiate discussions about the place of II in hospitality and tourism, a discussion which up until the present has been largely inexistent. However, our framework depicting the role and impact of II in STFs is not without limitations, having been derived from content analysing extant II and tourism literature. However, we hope to have provided a foundation upon which empirical studies can be developed to extend our understanding of and expand research on II in H&T. Future empirical research can expand our understanding and applicability of the framework by testing it in a real-life context in an emerging SSA country. Research can also explore how STFs that have received impact funds grapple with the challenge of delivering social, environmental and financial returns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term Small tourism firms in this article is used to denote all firms which are directly or indirectly operating in or are involved with the provision of goods and services to the hospitality and tourism industry. These will include small hotels, inns, leisure, F&B, caterers, tour, transport, health and security service operators/providers.

2 Additionality is an enterprise’s ability to increase the quantity or quality of its social outcomes beyond what would otherwise have occurred if there was no additional investment.

References

- Agrawal, A & Hockerts, K, 2019. Impact investing: Review and research agenda. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship. doi:10.1080/08276331.2018.1551457.

- Bannick, M & Goldman, P, 2012. Priming the pump: The case for the sector based approach to impact investing. Omidyar Network, Redwood City, USA.

- Battilana, J & Dorado, S, 2010. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal 53(6), 1419–1440. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.57318391

- Bauchet, B, Marshall, C, Starita, L, Thomas, J & Yalouris, A, 2011. Latest findings from randomized evaluations of microfinance. CGAP/The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Bosworth, G & Farrell, H, 2011. Tourism entrepreneurs in Northumberland. Annals of Tourism Research 38(4), 1474–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.015

- Brest, P & Born, K, 2013a. Unpacking the impact in impact investing. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Standford. http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/unpacking_the_impact_in_impact_investing Accessed 30 July 2018.

- Brest, P & Born, K, 2013b. When can impact investing create real impact? Stanford Social Innovation Review, Standford, CA. http://www.ssireview.org/up_for_debate/article/impact_investing Accessed 30 July 2018.

- Brest, P & Born, K, 2014. Giving thoughts: Deconstructing impact investing. http://boundlessimpact.net/wp-content/uploads/Deconstructing_Impact_Investing.pdf Accessed 24 September 2014.

- Brest, P & Harvey, H, 2008. Money well spent: A strategic plan for smart philanthropy. Bloomberg Press, New York.

- Bugg-Levine, A & Goldstein, J, 2011. Impact investing. Transforming how we make money. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

- Castellas, E & Ormiston, J, 2018. Impact investment and the sustainable development goals: Embedding field-level framesin organisational practice. Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research 8, 87–101. doi: 10.1108/S2040-724620180000008010

- CDC, 2014. One out of every 100 pupils in Kenya attends Bridge International Academies. http://www.cdcgroup.com/Media/News/One-out-of-every-100-pupils-in-Kenya-attends-Bridge-International-Academies/ Accessed 6 October 2018.

- CGAP, 2013. Where do impact investing and microfinance meet? The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Choda, A & Taladia, M, 2018. Conversations about measurement and evaluation in impact investing. African Evaluation Journal 6(2), 1–11. doi: 10.4102/aej.v6i2.332

- Dalberg, 2011. Impact investing in West Africa. A Report by Dalberg Global Development Advisors. http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/blog/impact-investing-west-africa Accessed 27 August 2014.

- Dalberg, 2012. Assessment of Impact Investing Policy in Senegal. http://dalberg.com/documents/Impact_Investing_Senegal_Eng.pdf Accessed 27 August 2014.

- Dallmann, J, 2018. Impact investing, just a trend or the best strategy to help save our world? https://www.forbes.com/sites/jpdallmann/2018/12/31/impact-investing-just-a-trend-or-the-best-strategy-to-help-save-our-world/#745d0ed675d1 Accessed 5 October 2019.

- DFID, 2014. The DFID impact fund first investment: Novastar Ventures. http://www.theimpactprogramme.org.uk/dfid-impact-fund/ Accessed 6 October 2014.

- Dolan, E, 2012. The new face of development: The ‘bottom of the pyramid’ entrepreneurs. Anthropology Today 28(4), 3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8322.2012.00883.x

- Findlay, S & Moran, M, 2019. Purpose-washing of impact investing funds: motivations, occurrence and prevention. Social Responsibility Journal 15(7), 853–873. doi: 10.1108/SRJ-11-2017-0260

- Fletcher, P, (Ed), 2011. Impact investment: Understanding financial and social impact from investments in East African agricultural businesses. PCP & The Gatsby Charitable Foundation, Kampala.

- Freireich, J & Fulton, K, 2009. Investing for social and environmental impact: A design for catalyzing and emerging industry. The Monitor Institute. http://monitorinstitute.com/downloads/what-we-think/impact-investing/Impact_Investing.pdf Accessed 29 July 2018.

- Friedman, E, 2013. Reinventing philanthropy: A framework for more effective giving. Potomac Books Inc, Dulles, VA.

- GIIN, 2011. Improving livelihoods, removing barriers: Investing for impact in Mtanga Farms. Global Impact Investment Network. https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/improving-livelihoods-removing-barriers-investing-for-impact.pdf Accessed 29 October 2019.

- GIIN, 2012. Diverse perspectives, shared objectives: Collaborating to form the African Agricultural Capital Fund. https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/diverse-perspectives-shared-objective.pdf Accessed 29 July 2018.

- GIIN, 2013. Perspectives on progress, global impact investing network, http://www.thegiin.org/cgi-bin/iowa/resources/research/489.html Accessed 20 October 2014.

- GIIN, 2016. The landscape for impact investing in Southern Africa. https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/Southern%20Africa/GIIN_SouthernAfrica.pdf Accessed 29 July 2018.

- Hope Consulting, 2010. Money for good: The US market for impact investments and charitable gifts from individual donors and investors. https://thegiin.org/assets/binarydata/RESOURCE/download_file/000/000/96-1.pdf Accessed 10 July 2019.

- Huppe, G & Silva, M, 2013. Overcoming barriers to scale: Institutional impact investments in low-income and developing countries. International Institute for Sustainable Development, Winnipeg, MB.

- Jackson, E & Harji, K, 2017. Impact investing: Measuring household results in rural West Africa. ACRN Oxford Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives 6(4), 53–66.

- Jin, H, Moscardo, G & Murphy, L, 2017. Making sense of tourist shopping research: A critical review. Tourism Management 62, 120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.027

- Johnson, K & Lee, H, 2013. Impact investing: A framework for decision making. Cambridge Associates LLC, Boston, MA.

- Kania, J & Kramer, M, 2011. Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Standford, CA. http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact Accessed 15 July 2018.

- Kimbu, NA, 2011. The role of transport and accommodation infrastructure in the development of eco/nature tourism in Cameroon. Tourism Analysis 16(2), 137–156. doi: 10.3727/108354211X13014081270323

- Kimbu, NA & Ngoasong, MZ, 2013. Centralized decentralization of tourism development: A network perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 40, 235–259. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.09.005

- Kimbu, AN & Ngoasong, MZ, 2016. Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research 60, 63–79. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.002

- Kimbu, AN, Ngoasong, M, Adeola, O & Afenyo-Agbe, E, 2019. Collaborative networks for sustainable human capital management in women’s tourism entrepreneurship: The role of tourism policy. Tourism Planning & Development 16(2), 161–178. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2018.1556329

- Koh, H, Karamchandani, A & Katz, R, 2012. From blueprint to scale: The case for philanthropy in impact investing. Monitor Group in collaboration with acuMEn Fund. https://www.philanthropy-impact.org/sites/default/files/downloads/2013_07_09blueprint_to_scale.pdf Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Kwaramba, HM, Lovetta, JC, Louwb, L & Chipumuroc, J, 2012. Emotional confidence levels and success of tourism development for poverty reduction: The South African Kwam-Makana home-stay project. Tourism Management 33(4), 885–894. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.09.010

- Lehner, O, Harrer, T & Quast, M, 2018. Building institutional legitimacy in impact investing. Journal of Applied Accounting Research. doi:10.1108/JAAR-01-2018-0001.

- McCreless, M & Trelstad, B, 2012. A GPS for social impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review 10(4), 21–22.

- Mogapi, E, Sutherland, M & Wilson-Prangley, A, 2019. Impact investing in South Africa: Managing tensions between financial returns and social impact. European Business Review 31(3), 397–419. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2017-0212

- Ngoasong, MZ & Kimbu, AN, 2016. Informal microfinance and development-led tourism entrepreneurship. Tourism Management 52, 430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.012

- Ngoasong, MZ & Kimbu, AN, 2019. Why hurry? The slow process of high growth in women-owned businesses in a resource-scarce context. Journal of Small Business Management 57(1), 40–58. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12493

- Ngoasong, MZ, Paton, R & Korda, A, 2015. Impact investing and inclusive business development in Africa: A research agenda. The Open University, Milton Keynes.

- O’Donohoe, N, Leijonhufvud, C, Saltuk, Y, Bugg-Levine, A & Braddenburg, M, 2010. Impact investments: an emerging asset class. Jp Morgan Global Research and the Rockefeller Foundation. https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/Impact%20Investments%20an%20Emerging%20Asset%20Class2.pdf Accessed 05 November 2019.

- Olsen, S & Galimidi, B, 2008. Catalog of approaches to impact measurement: assessing social impact in private ventures. Social Venture Technology Group/Rockefeller Foundation. http://svtgroup.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/SROI_approaches.pdf Accessed 15 July 2018.

- Ormiston, J, Charlton, K, Donald, S & Seymour, R, 2015. Overcoming the challenges of impact investing: Insights from leading investors. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 6(3), 352–378. doi: 10.1080/19420676.2015.1049285

- Park, H, Cho, I, Jung, S & Main, D, 2015. Information and communication technology and user knowledge-driven innovation in services. Cogent Business and Management 2(1), 1–18.

- Roundy, P, 2019. Regional differences in impact investment: A theory of impact investing ecosystems. Social Responsibility Journal. doi:10.1108/SRJ-11-2018-0302.

- Roundy, P, Holzhauer, H & Dai, Y, 2017. Finance or philanthropy? Exploring motivations and criteria of impact investors. Social Responsibility Journal 13(3), 491–512. doi: 10.1108/SRJ-08-2016-0135

- Rozas, D, Drake, D, McKee, ELK & Piskadlo, D, 2014. The art of the responsible exit in microfinance equity sales. CGAP & CFI, Washington, DC.

- Saldinger, A, 2014. What’s next for impact investing: Definitions, measurement, and rising expectations. Devex Impact: Impact investing 2.0. https://www.devex.com/news/what-s-next-for-impact-investing-definitions-measurement-and-rising-expectations-83781 Accessed 8 December 2018.

- Sandberg, J, Juravale, C, Hedesström, TM & Hamilton, I, 2009. The heterogeneity of socially responsible investment. Journal of Business Ethics 87, 519–533. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9956-0

- Scholtens, B, 2014. Indicators of responsible investing. Ecological Indicators 36, 382–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.08.012

- Staub-Bisang, M (Ed.) 2012. In Sustainable investing for institutional investors: Risk, regulations and strategies. John Wiley & Sons, Singapore.

- Tekula, R & Anderson, K, 2019. The role of government non-profit, and private facilitation of the impact investing marketplace. Public Performance & Management Review 42(1), 142–161. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2018.1495656

- The Parthenon Group and Bridges Ventures, 2010. Investing for impact: Case studies across asset classes. https://thegiin.org/research/publication/investing-for-impact-case-studies-across-asset-classes Accessed 8 November 2019.

- The Rockefeller Foundation, 2012. Accelerating impact: Achievements, challenges and what’s next in building the impact investing industry. E.T. Jackson and Associates Ltd for Rockefeller Foundation, New York.

- Tichaawa, TM & Kimbu, AN, 2019. Unlocking policy impediments for service delivery in tourism firms: Evidence from small and medium sized hotels in sub-Saharan Africa. Tourism Planning & Development 16(2), 179–196. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2018.1556328

- UNDP, 2015. Impact investment in Africa: Trends, constraints and opportunities. United Nations Development Programme Regional Service Centre for Africa, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Urban, B & George, J, 2018. An empirical study on measures relating to impact investing in South Africa. International Journal of Sustainable Economy 10(1), 61–77. doi: 10.1504/IJSE.2018.088622

- WEF, 2013. From ideas to practice, pilots to strategy: Practical solutions and actionable insights on how to do impact investing. A report by the WEF Investors Industries. WEF, Davos.

- WEF, 2014. Charting the course: How mainstream investors can design visionary and pragmatic impact investing strategies. A report by the WEF Investors Industries prepared in collaboration with Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. WEF, Davos.

- WTTC, 2019. Travel & tourism continues strong growth above global GDP. https://www.wttc.org/about/media-centre/press-releases/press-releases/2019/travel-tourism-continues-strong-growth-above-global-gdp/Accessed 4 November 2019.

- Zhao, W, Ritchie, JRB & Echtner, CM, 2011. Social capital and tourism entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research 38(4), 1570–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.02.006