ABSTRACT

In view of inclusive growth (IG), a critical research question is: What adjustments to the growth process are necessary to ensure inclusive development? In attempting to answer this question, the paper investigates the concept of inclusive growth from different perspectives and examines the challenges and policy priorities for inclusive growth in the African context. Essential components of inclusive growth are identified. Given the promise it holds to help overcome the pressing obstacles of poverty, unemployment and inequality in a broad-based manner, IG is seen as instrumental in increasing Africa’s economic inclusivity. The question of how inclusive the growth of African economies ought to be, is essential for ensuring sustainable development, considering rising population growth rates. The paper makes a contribution to mapping the way forward towards reaching this goal. Key findings are a reinterpretation of genuine growth and how inclusivity criteria can be used to achieve it.

1. Introduction

As the world entered the twenty-first century, there has been a growing demand for economic inclusiveness, especially with regards to growth. Focus on inclusive growth (IG) has increased among analysts and policymakers, as evidenced through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Yet, much research still needs to be done to gain clarity on the meaning and measuring of IG as well as the implementation of IG-strategies and – adjustments in economies. African countries are concerned about the lack of inclusiveness, especially given high economic growth rates in many countries during the past two decades. Creation of job opportunities and the reduction of poverty and inequality remain sedentary, resulting in low productivity.

According to Ncube (Citation2015:172), African economic growth has not been inclusive, thus threatening its sustainability, especially because its growth can mostly be explained by a strong, but fluctuating, commodity price trend, adding to its economic vulnerability. Ali & Son (Citation2007:1) point out that high and increasing levels of income inequality can lower the impact of growth on poverty reduction, resulting in negative implications for political stability and social cohesion, which are needed for sustainable shared growth. Even in advanced economies, growth has accompanied rising income inequality over the last 30 years, spurring the debates on development, poverty and the inclusiveness of growth (OECD, Citation2014:7). Rising unemployment, especially in Africa, has further underlined the need for an improved understanding of the policy-frameworks needed to enhance labour market outcomes across various social groups. By and large, African women and youth are particularly vulnerable due to their weak attachment to the labour force, thus inhibiting broad-based growth. In addition, demand for access to services are pressuring national budgets. All these factors call for more inclusive models of growth.

Africa’s accelerated growth is laudable (on average, over 5% since 2000), but its limits are quite varied. The unequal distribution of the benefits of growth has constrained its impact on poverty reduction and job creation (Ncube, Citation2015:154). Jobless growth, among other things, is a serious reality that Africa urgently needs to address. Almost 40 million Africans are unemployed, while the average poverty rate remains above 40% (AfDB, Citation2016:365). Growth has to become more inclusive and pro-poor to bring about the needed structural transformations in African economies and improve the well-being of even the non-income components of society, such as health and education. The exclusion of disadvantaged groups further stresses that the nature of growth needs to adjust. Africa faces an uncertain future as its youth (those below 19 years of age) comprise more than 50% of the population and have very limited choices and capabilities. Three out of four Africans live in poor conditions, compared to one in five globally (ILO, Citation2012). Both the short- and long-term implications of this necessitates a radically inclusive approach to stimulating growth and development to ensure genuine economic progress, which should also include green growth. The question is: What adjustments to the growth process are necessary to ensure inclusive development? The paper investigates this question and attempts to bring clarity to the interpretation, components and policy priorities of inclusive growth in the African context, which could help ensure sustainable development.

2. What is inclusive growth?

Inclusive growth (IG) is not simply another description of economic development; it is growth which is such that it actually leads to development. IG focuses more on the process of growth and the outcomes of growth (shared benefits) than simply output. As articulated within the SDGs, IG combines growth with social aspects, emphasising the need to share economic growth with the poorest. When growth is truly inclusive, development would be a natural outcome.

What then is inclusive growth? It is utilising every productive component optimally in the production process by way of inclusion, not exclusion/filtering. A variety of interpretations to this exist, which will be elucidated. Firstly, organic growth values all participants’ unique and significant function in the production process and attempts to reward it equitably. A blossoming tree is an accurate analogy of this, because it does not use exclusion to grow, rather expansion (inclusion). Organic growth is multi-directional (in that all cells, in other words, productive units, contribute), and not just one-directional ‘profit-seeking’. Growth and replenishing, therefore, go together in this broader concept of growth, thus ensuring sustainability and exponential growth potential.

As Vasudev (Citation2013:1) underlines: ‘big business is not about profit but expansion; expansion is inclusion. Inclusive [growth] is a way of empowerment of the whole of humanity to participate in a robust and all-inclusive economic process’ (including quality education and health care that lead to growth). This opens the way for a faster rise in poor people’s well-being than non-poor people. It also minimises the possibility of immiserising growth (negative growth) where growth occurs while a country’s terms of trade weaken (Bhagwati, Citation1958:202). Organic expansion-growth increases the probability that export earnings will increase faster than import costs due to the diversification of the economy.

Another interpretation of inclusive growth (IG) is pro-poor growth, in that the latter focuses exclusively on the outcomes of growth in terms of its effect on the income of poverty-stricken people. This can either be in the context of relative poverty (i.e. when the poor’s income improve relative to the non-poor) or in terms of absolute poverty (i.e. when fewer people end up below the poverty line). With broad-based growth, which is another interpretation of IG, the aim is to involve more poor and disadvantaged people in the growth process through employment (producing goods and services) (Fourie, Citation2014:3). A fourth interpretation is shared growth, which emphasises that the fruits of growth be shared in a way that eliminates poverty and drastically reduces income inequality (AsgiSA, Citation2006:6). Shared growth is focussed on people’s quality of life as they participate in production.

As Fourie (Citation2014:2) highlights, the concept of inclusive growth

attempts to define a broader concept of economic growth that incorporate equity and the well-being of all sections of the population – notably the poor, with poverty being considered either in absolute terms (poverty reduction) or relative terms (the reduction of inequality).

In confirmation of this new emphasis, there has been a significant advancement in terms of re-evaluation (since the Rio Summit 1992) of what ‘economic progress’ means. A holistic perspective on growth is developing, emphasising the needed inclusivity of growth and less growth-centered economic progress. Growth will always remain important, but a variety of new indicators have been put forward by advocates of inclusive development, which is argued to be more appropriate (than merely gross domestic product (GDP)) for evaluating the performance of economies, the global economy, businesses, institutions and communities (Pouw & McGregor, Citation2014).

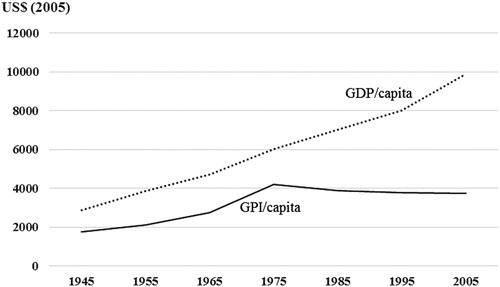

One such indicator is the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI). The GPI incorporates environmental and social factors, which are not measured by GDP. When poverty, for instance, increases, GPI would decrease. It factors in environmental footprints and social costs resulting from business activity. A range of indicators are combined (as plusses and minuses) in accounting for genuine economic progress. Whereas GDP might be seen as the ‘gross profit’, GPI is seen as the ‘net profit’ (or GPI balances GDP spending against external costs). below illustrates this by showing that although global GDP per capita has increased, genuine progress and well-being have not, since global GPI per capita is on a decreasing trajectory (from 1975 to 2005). While GDP is a measure of current income, GPI measures the sustainability of that income – which, as is clear from , is of major concern for inclusive growth.

Figure 1. Global GDP per capita vs. global GPI per capita. Source: Kubiszewski et al., Citation2013.

Genuine economic progress means improvement in all forms of human well-being, resulting in truly inclusive, sustainable development. Costanza et al. (Citation2009:12) define this as ‘development that improves the quality of human life while living within the carrying capacity of supporting ecosystems’. The World Commission on Environment and Development emphasised meeting ‘the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Citation1987:8). This is inclusive growth combining with genuine economic progress.

The last interpretation of IG here, i.e. green growth, hence surfaces. Green growth refers to a circular model of the economy, instead of the current linear model. This means that rather than continuing to ‘make, use and dispose’ unwanted side-effects in the economy (such as for instance, at least one third of the world’s plastic waste being neither collected nor managed, and most of it ending up in the oceans), such side-effects must become a thing of the past (Lorek & Spangenberg, Citation2013). In a circular economy, a given resource is kept circulating for as long as possible, thus benefiting the environment. This means designing products, processes and services to optimise the use of resources; and when such resources reach the end of their lifespan, they are either re-used, repaired or re-manufactured for another use. True to IG, one should also be able to re-inject their composite materials elsewhere into the economy. This ‘circularity’ principle of green growth should especially be built into energy, transport and construction as key growth drivers. This would also bring about greener agriculture, preserving biodiversity and ecosystem services as adjusted business models are being applied.

Inclusive growth is thus a comprehensive concept and can be interpreted in multifaceted ways. From all the above, the following criteriaFootnote1 for inclusive growth could provide clarity on what it is about and what changes to the growth process are necessary for it to be more inclusive:

Optimal productivity (inclusive and organic expansion)

Pro-poor growth

Broad-based growth

Shared growth

Genuine economic progress (GPI-indicator)

Green growth (building a circular economy).

3. Brief overview of empirical work on inclusive growth

Defining inclusive growth as ‘growth that not only creates new economic opportunities, but also one that ensures equal access to the opportunities created for all segments of society, particularly for the poor’, Ali & Son’s (Citation2007:12) empirical work on IG is based on a social opportunity function, much like a social welfare function. Arguing that IG leads to the maximisation of the social opportunity function, they base the latter on two factors: (1) average opportunities available to the population, and (2) how opportunities are shared/distributed among the population. By using a weighting scheme model, greater weight is allocated to the opportunities of the poor, making that more important than opportunities created for the non-poor. Ali and Son found that when opportunities enjoyed by a person are transferred to a poorer person, then social opportunity increases, thus making growth more inclusive. In building an opportunity index, this was applied to the Philippines using the Annual Poverty Indicator Survey (1998–2004). An opportunity curve was empirically calculated using unit record household surveys. The interpretation was that the higher the opportunity curve, the greater the social opportunity function will be. This type of dynamic analysis can then be used to assess how the opportunity curves shift between different periods. Hence, the degree of growth inclusiveness will depend on (1) how much the curve shifts upward; and (2) in which part of the income distribution the shift takes place.

Anyanwu (Citation2013) proceeded by making use of a growth-poverty model for a regression analysis to establish the relationship between growth and poverty in measuring inclusive growth. Anyanwu used national representative poverty surveys from 1980 to 2011, in which the dataset consists of 43 African countries. Some key empirical results were:

greater inequality is associated with higher poverty in Africa (one per cent increase in income inequality lead to a 1.31% increase in the share of people living in poverty);

foreign aid is vital to poverty reduction in Africa (a one per cent increase in net Official Development Assistance as percentage of GDP lead to 0.29% decline in poverty);

a one per cent increase in population causes an increase of poverty by over 0.19%;

inflation increases poverty in Africa (a one percent increase in the inflation rate would increase poverty by as much as 1.7%); and

a one per cent increase in real per capita GDP would reduce poverty in Africa by 0.74%, suggesting that any inclusive growth strategy has to ensure that countries ‘climb the ladder’ of economic development.

Furthermore, an Inclusiveness Index has been developed at the International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (Fourie, Citation2014). It contains three, equally-weighted components: two outcomes-based, or benefit-sharing measures, more specifically a measure of poverty and a measure of income inequality; and one process-based measure, more specifically a measure of employment participation. The indicators are:

for participation: the employment-to-population ratio (EPR), i.e. the absorption rate; and

for benefit sharing: the poverty headcount ratio (H) and the Gini coefficient (G).

A developing country’s index is calculated relative to the data of the other developing countries that are analysed. It represents a country’s position regarding poverty, inequality and employment relative to the best situations within the group of countries.Footnote2 The Index is constructed on a scale ranging from 0 to 1 (Fourie, Citation2014). A higher index value implies a worse performance in terms of inclusiveness. Countries with a poverty rate of more than 65% are summarily classified as non-inclusive and given the highest index value possible, i.e. 1. Examples include Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, Ethiopia, Madagascar and India (between 1996 and 2006).

The situation in these countries are worse than that of, for instance, South Africa, which had an Inclusiveness Index value of 0.77 during the same period (Ramos et al., Citation2013:9). While this is very high, Tunisia is the only African country that was more inclusive than South Africa (0.43 index value in 2006).

Compared to other developing countries, most African countries have a very low degree of inclusiveness, which is largely the result of a low labour absorption rate and very high income inequality. South Africa’s inclusivity has, for instance, declined since 1996. Amidst high GDP growth rates, its index has climbed from 0.74 in 1996 to 0.77 in 2006. In this period, the only positive element was the declining poverty ratio – but it was overshadowed by growing inequality and a declining employment-to-population ratio (EPR).

For economic growth as such to be considered inclusive, it must either lead to an improvement in all three these indicators of inclusivity, or at least an improvement in one or two indicators but with the other indicator(s) stable/non-deteriorating (Ramos et al., Citation2013:35). Africa’s growth has thus not been inclusive during this period, or after that, particularly because of the global financial crisis. Unemployment is the critical factor, because its reduction will improve African countries’ EPR, poverty reduction and inequality. By attracting more foreign investment and stimulating entrepreneurship and skills development, South Africa can, for example, improve on almost all the inclusivity criteria (except perhaps for green growth) and ensure that both ‘participation’ and ‘benefit sharing’ improve. Other African countries have a similar situation in this regard, hence this presents a clearer picture of how their economies can overcome the challenges to inclusive growth.

4. Growth debate in the African context

African economic growth has slowed down significantly to 2.2% in 2016 and 3% in 2017, compared to 3.4% in 2015 and 7% in 2012 (AfDB, Citation2018:5). The main reason for this is the poor performance of Africa’s leading economies during that period, Nigeria and South Africa, which accounted for 29.3% and 19.1% of the share in Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP), respectively (AfDB, Citation2017:32). Nigeria (GDP of −1.5% in 2016) experienced a recession at the time, worsened by the fall in oil prices and policy uncertainties. In turn, South Africa (GDP of 0.3% in 2016 and 1.3% in 2017) was still recovering slowly from an electricity deficit and persistent droughts, while the 2017 economic downgrade to sub-investment status continued its negative impact into 2018.

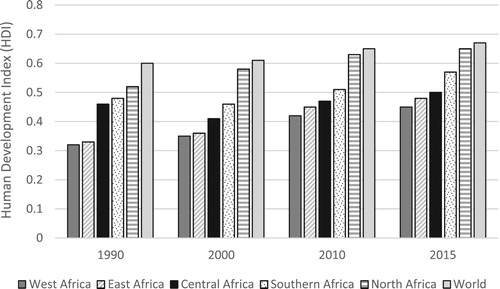

As an inclusivity indicator, shows that Africa’s human development levels remain below the world average. Foreign direct investment (FDI) also remains volatile due to African domestic risks and global uncertainties.

Figure 2. African regions: Human development levels (1990–2015). Source: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Citation2016.

Persistent non-inclusion of segments of society is likely to undermine economic growth and bring destabilisation. While the scale and scope of the inequality of growth may vary between countries and regions, many societies struggle to reach inclusive growth as a result of the increasing income gap between the rich and the poor, disparities in education opportunities, and dissatisfaction with employment opportunities. The African Development Bank (AfDB, Citation2012) has identified the following five key challenges to inclusive growth in Africa:

Infrastructure: financing restrictions, weak regulatory environments, limited/no access to electricity and water;

Regional integration and trade: lack of collaboration and sharing productive capacities limit competitiveness; more market access needed;

Private sector development: low productivity rates resulting in non-attraction of investment/capital; inefficient, labour-intensive farms;

Weak governance institutions and instruments: deficient standards and conditions for fostering resource mobilisation; weak contract enforcement and non-protection of property rights; and

Education: lack of access to quality education (especially in rural areas).

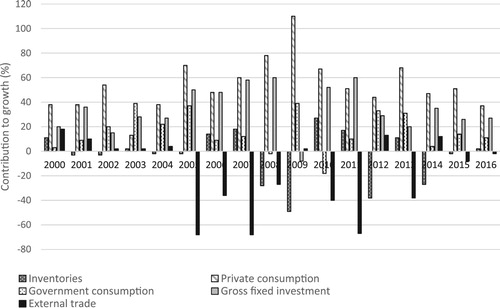

These hurdles to inclusive growth have also resulted in the main drivers of Africa’s economic growth not being as inclusive as they should be. In this regard, according to , private consumption has on average (from 2000 to 2016) been the best performer, followed by gross fixed investment and government consumption. The worst performers are external trade and inventories. Population growth contributed to increased domestic demand, outperforming natural resources and primary commodities as a major growth driver. It also contributed to a rise in entrepreneurship, which is expected to lead to more investment in industrialisation (AfDB, Citation2017:29). Public infrastructure investment would complement this in stimulating government consumption’s contribution to growth. A concern is the relatively low levels (over the 17- year period in ) of almost all the growth drivers since 2010.

Figure 3. Drivers of growth in Africa (2000–2016). Source: World Bank, Citation2016; AfDB, Citation2017:29.

The main concern is the low level of inclusivity that these growth drivers are characterised with in terms of building a more inclusive economy in Africa. This will become clearer when we consider the meaning and components of inclusive growth and whether these drivers contribute substantially to reducing economic inequality. Africa’s inequality ratio, as indicated by the Gini coefficient, is 0.43 (compared to 0.39 for other developing countries) (Bhorat et al., Citation2016:12). By global comparison, Africa has the largest differences in distribution of benefits of human progress. The overall loss in human development (i.e. a worsening of the human condition) from inequality in Africa is 32%, which is much higher than the global average of 22% (AfDB, Citation2017:111).

In further seeking answers to making Africa’s economic growth more inclusive, the growth debate needs to be taken under the microscope in the African context. Firstly, the term ‘growth’ needs to be clarified. Daly (Citation1987:323) describes it as

a quantitative increase in the scale of the physical dimensions of the economy; i.e. the rate of flow of matter and energy through the economy (from the environment as raw material and back to the environment as waste), and the stock of human bodies and artifacts.

Two specific areas of debate relevant to inclusive growth in Africa are the limits to growth and financial inclusion. The limits of growth concern the fact that growth does not guarantee development in the economy. Growth is limited in both its biophysical capacity and its ethicosocial capacity. The former comprises three interrelated conditions – finitude, entropy, and complex ecological interdependence (Daly, Citation1987). It underlines that the economy is dependent on a finite ecosystem, which is both the supplier of raw materials and the absorber of its entropy wastes. Interference in the ecosystem through disorder (depletion and pollution) directly affects the capacity of the economy, especially its growth capacity (products, services, sustained consumption). The latter, ethicosocial limits, refer to (1) the financing of growth being limited by the cost it imposes on future generations; (2) the degree to which the self-cancelling effects on welfare can limit growth (e.g. higher dependency on grants); and (3) the social impact of growth, such as rising inequality (e.g. supercapitalism benefiting the rich and the poor increasingly being excluded from mainstream economic activity) (Dierckxsens, Citation2000:31).

Notably, neoclassical economics do not fully assume these limits. As Abramowitz (Citation1979:18) points out, ‘Economists have relied, however, on a practical judgment, namely, that a change in economic welfare implies a change in total welfare in the same direction, if not in the same degree’. This practical judgment ceases to be true as the economy approaches either or both limits. The gain in (and sustainability of) economic welfare could easily be more than offset by a loss of natural ecosystem services provoked by excessive production, or by a deterioration/insufficiency of the redistribution channels of the economy, resulting in the escalation of economic inequality. Given current African realities, economic growth means that close-to-the limits cases become increasingly the norm. The nearer we are to limits, the less we can assume that economic welfare and total welfare move in the same direction (i.e. development). Rather, we must learn to define and explicitly account for other sources of welfare that growth inhibits, and erodes, when pressing against limits. ‘The economics of an empty world with hungry people is different from the economics of a full world, even when many do not yet have the full stomachs, full houses, and full garages of the “advanced” minority’, argues Daly (Citation1987:324).

The other area of debate involves the issue of financial inclusion in the growth process. The weak performance in many African countries on access to finance is a serious concern. The question is: To what extent would greater financial inclusion – which is on balance (in the short term) a cost to banks – lead to increased economic growth in Africa? According to the endogenous growth theory, there are mainly two channels through which finance affects the real economy: the efficiency with which savings are allocated to investment; and an increase in financial intermediation can affect growth if it improves the allocation of capital (Ikhide, Citation2015). An improvement in the allocation of capital (e.g. through financial inclusion) should thus lead to higher growth, since it raises the total productivity of capital.

In the interdependency between growth and finance, the direction of causality can run either from the financial sector to the real sector (supply-leading hypothesis), or that economic growth leads to financial development (demand-following hypothesis) (Demetriades & Hussein, Citation1996). In studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the former have mostly been found to be the case (Adjasi & Biekpe, Citation2006; Enisan & Akinlo, Citation2007). It could be explained partly by Africa’s underdeveloped financial systems, but overall results in support of finance-led growth have mostly been tepid. The debate on the direction of causation remains a controversial issue, especially in Africa, because of examples being so few where financial development has led to economic growth. However, this does not diminish the fact that, in principle, a strong correlation exists between the exogenous components of financial development and long-run economic growth. And in both contexts, increased financial inclusion (i.e. banking the unbanked) is intrinsic to inclusive growth. In a study by Demirguc-Kunt et al. (Citation2017), financial inclusion helps reduce poverty and inequality as it helps people invest in their future; stimulates consumption; and equips people to manage financial risks better. Bruhn & Love (Citation2014) found that increased access to financial services leads to an increase in low-income individuals’ income by allowing informal business owners to keep their businesses open, thus creating employment opportunities.

5. Policy priorities for inclusive growth in the African context

Central to inclusive growth is stamping out inequality and constructing a responsible economy; that is, where care is taken of each person, and where an improvement in the collective well-being is the main aim of development. African collectivism naturally prioritises this through the revered Ubuntu-principle. Such an inclusive economy is markedly different from a market-and-growth-centred economy where growth and production are essentially the only providers of progress in welfare. Income might increase, but quality of life often suffers because of serious flaws in the market and growth process (e.g. maldistribution, pollution, worker exploitation, societal degradation/ disconnection and excessive competition). From a policy perspective, African economics must steer clear of this approach and embrace a collectivistic alternative. In an inclusive development framework, the three dimensions/types of individual and collective well-being – material, cognitive/subjective and relational – are holistically taken into consideration in a value-driven economy, geared towards reducing the trade-offs between the different types of well-being. Synergies (between collective and individual well-being) and empowerment (better decisions for an improved quality of life) rather become the goals. Policy frameworks geared more toward these priorities would steer more effectively in the direction of inclusive growth.

Then, collectively in the African society, as Ray & Liew (Citation2003:386) point out, empowerment occurs as ‘social interactions enable individuals to adapt and improve faster than biological evolution based on genetic inheritance alone’. This emphasises a heuristic understanding of economic decision-making guided by multiple (codified) rules, laws and values simultaneously, which distinguishes itself from the simplistic utility function in welfare economics where only one rule applies: efficiency. Inclusive growth priorities take better cognizance of complex human well-being decisions to see the tangible improvement of communities’ well-being. With collective well-being the primary objective of economic policy, the economy is moved in the direction of genuine progress and inclusive growth. Emphasising communal well-being (not just profits) is therefore integral to the transformation towards creating a sustainable, equitable and inclusive African economy.

In this regard, Verstappen (Citation2011:6) also identifies family relationships, work, friends, health, personal freedom, and spiritual expression as essential ingredients of collective well-being. Stiglitz et al. (Citation2009:14) underscore this multi-dimensional understanding of well-being, and add to this list: education; political voice and governance; and reducing survival-insecurity. When prioritising collective well-being, conventional economic growth only is insufficient, because unless distribution and sustainability are at least equally efficient, growth is not viable to improve well-being consistently. As a policy objective, it is particularly the prioritisation of the social (broader) conception of well-being that inclusive growth steers towards.

This coincides with prioritising what is called ‘ethonomics’ (improving the common good). This is an economics of sharing, connecting, collaborating, openness and ethics that also value non-market goods, normally devalued by an increasingly market-dependent global citizenry (Verstappen, Citation2011:7). Ethonomic-sensitive policies bring about a re-evaluation of what assets we exchange; why and how we do so; and how to value these assets properly. It draws attention to elements of society that are not ruled by the market-mechanism; that do not follow the logic of accumulation and competition; and are not based on the pursuit of self-interest. It shifts the focus more towards improving the value of the common good and collective interest. This is particularly relevant for Africa, as it fits better into the Ubuntu-paradigm inherent in African thinking and social organisation. This explains why an inclusive growth process is more feasible in Africa and why economic policies that prioritise this are highly needed. To fully embrace collective well-being, this requires an enhanced understanding of development, as it lies in the interplay of individuality and sociality, of individual initiative and social integration, and of individual autonomy and social cohesion. If the common good is to be identified in African economies, then a new appreciation of human relationships – even power relationships (e.g. employer-employee or levels of governance,) – are essential to inclusive development and growth, together with the moral dimensions of decision-making, to ensure that the needs of well-being are holistically met (and not exploited by the rich). In this way, collective well-being becomes a unifying and central goal of economic performance and social progress in Africa, which is different from (selective/unequal) material welfare only, as seen around the world. The very promising possibility therefore exists that Africa can distinguish itself through such inclusive growth-enhancing policies in order to open the way for truly inclusive development. The latter start valuing a broader, more holistic spectrum of diversity related to humans (Africans) as fundamental economic role players.

Growth will not be inclusive unless we make it inclusive. Conventional growth only cannot reduce poverty and inequality and increase employment (Ramos et al., Citation2013:36–7). The trickle-down effect is not working effectively, especially not in Africa where economic growth is not accompanied by the generation of adequate employment. A key policy priority for Africa is, therefore, realigning growth patterns to become employment intensive. If, for instance, the employment coefficient in Africa is approximately 0.5 then employment expands at only half the rate of GDP growth. As a consequence, the absorption of labour will continually decrease relative to output, implying that overall employment intensity keeps declining. This is a general problem in Africa. Policies to increase employment must go further than only stimulate growth in the core, formal economy. Developing and investing in the informal economy becomes critical in stimulating inclusive growth. If by definition, inclusive growth means and requires that poor and marginalised people participate in the growing economic activity and simultaneously benefit from it, inclusivity as a concept and as an economic policy strategy will have to include and integrate the informal and survivalist segments of the economy.

If African economic policy could develop untapped economic and employment potential in the informal sector, together with efforts to stimulate the demand for unskilled and semi-skilled labour in the formal sector, such inclusivity could produce an economic growth trajectory that would increase the scope and value of economic activity and income in the informal economy (and the survivalist segment) as well (Fourie, Citation2014). Income-generating activities in the informal sector would become an integral part of growing economic activity and the collective good. Poor and marginalised people would contribute to growth – rather than just receive benefits from formal sector growth (e.g. social spending or grants). This would also help reduce the dependency ratio of Africans, thus generating inclusive growth and development.

Pursuing and attaining such inclusive growth would clearly require an explicit policy strategy to increase productive activity, employment, self-employment and earnings in both informal and formal segments of African economies, to develop durable backward and forward linkages between these segments and facilitate sustainable transitions into employment (Fourie, Citation2014). It requires a deep look, by private and public sectors alike, at the nature of production, distribution and employment processes. Structural and policy-induced factors that marginalise and exclude disadvantaged people from participating in employment and work, need to change. The same holds for worker earnings and the inequality of income. Appropriate legal and regulatory frameworks to support these policy adjustments, which could include elements of formalisation that are carefully selected to be enabling, would also be necessary – at all levels of government.

Lastly, in moving to greener inclusive growth, taxation should also be re-thought by African governments so as to move it from labour to pollution and resources. This would help stop subsidisation of activities that are detrimental to the environment, and encourage industry to follow a longer-term view and invest in less resource-intensive technologies. With resources becoming finite as consumption increase and resource replacement is slow, African economic policies will have to promote a circular economic model to attain inclusivity targets. In prioritising it collectively, it needs to become a natural way of thinking to policy-makers, the private sector, investors, and consumers. Strong political will, supported by an active civil society, is needed to implement these policy priorities in Africa.

6. Conclusion

The newly-introduced Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) exemplify the global shift towards more inclusive economies. However, if inclusive growth is not prioritised and pursued, then ‘inclusive economies’ will remain wishful thinking, especially in Africa. While the importance of growth and productivity is not questioned, the process, output and well-being impact of growth is under the microscope when zooming in on inclusive growth. The paper contributes to a reinterpretation of genuine growth by classifying needed adjustments to the growth process in seeking to follow a more inclusive approach to stimulating growth. For this purpose, six requirements (criteria) were identified as components of inclusive growth, to be employed jointly in economies: optimal productivity (involving organic output); pro-poor growth; broad-based growth; shared growth; genuine economic progress; and green growth (moving from the current high-wastage linear economy to a circular economy). Two distinctive features to ensure that the growth process is inclusive, which is of particular significance to Africa, are also crucial: it must be expressly non-discriminatory (improving participation); and be expressly disadvantage-reducing (improving benefit-sharing). These adjustments to the growth process will assist substantially in ensuring inclusive development.

Most African economies – even South Africa – severely lack economic inclusivity, given low levels of inclusive growth. Unemployment (especially youth unemployment) is identified as a most critical factor in building a more inclusive economy. Both in terms of the process and outcome of growth, reducing unemployment would improve almost all the inclusive growth criteria and features (mentioned above). This is vital for improving Africa’s collective well-being and genuine progress. So also are the production and distribution processes within African economies, which need to become more inclusive and less marginalising of the poor in their effect. Making such inclusive structural adjustments to African economies are pivotal policy priorities, given the long-term benefits these adjustments create for all. Together with this, Africa’s Ubuntu-mindset also lends itself to building a more circular economy to reduce wastage, optimise efficiency and having greener, inclusive growth in Africa. Given African people’s strong inclination towards inclusivity, the desirable mental framework is already in place to pilot and pioneer inclusive growth strategies.

As much as the private sector should explore adjustments in production processes toward creating a more inclusive economy, the government in regulation and policy need to have the will-power to steer much-needed changes. In Africa, this is critical, since greater emphasis on inclusive growth presents a promising opportunity to address persisting economic exclusion, as a result of unemployment, poverty and lack of market access. This would even help steer consumption patterns to adjust to inclusive growth requirements. All these adjustments are instrumental in helping Africa take advantage of the opportunity to broaden the growth base and empowering the people of Africa to make sustainable contributions to the economy in terms of capacity development, creativity and entrepreneurship. Ubuntu necessitates inclusive growth. Some empirical work has been done on inclusive growth, but further research is much needed – especially in the African context – to deepen understanding of the possibilities, and the measuring, of inclusive growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This set of criteria for inclusive growth is not exhaustive, since more criteria could be identified. These are just the ones identified within the context of this study. It is, though, a necessary starting point for exploration.

2 The Inclusiveness Index is built through a min–max normalisation of data on poverty, inequality and the inverse of the EPR. The index is the simple average of the three min–max normalisations. See Ramos et al. (Citation2013).

References

- Abramowitz, M, 1979. Economic growth and its discontents. In Boskin, M (Ed.), Economics and human welfare. Academic Press, New York.

- Adjasi, C & Biekpe, N, 2006. Stock market development and economic growth: The case of selected African countries. African Development Review 18(1), 144–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8268.2006.00136.x

- AfDB (African Development Bank), 2012. AfDB’s long-term strategy: Inclusive growth agenda. Briefing note 6, 1–9.

- AfDB (African Development Bank), 2016. African Economic Outlook 2016. Report on sustainable cities and structural transformation. AfDB, Abidjan.

- AfDB (African Development Bank), 2017. African Economic Outlook 2017. AfDB, Abidjan.

- AfDB (African Development Bank), 2018. African Economic Outlook 2018. AfDB, Abidjan.

- Ali, I & Son, H, 2007. Measuring inclusive growth. Asian Development Review 24(1), 11–31.

- Anyanwu, J, 2013. Determining the correlates of poverty for inclusive growth in Africa. Working Paper Series 181, African Development Bank, Tunis, Tunisia.

- AsgiSA (Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa), 2006. Accelerated and shared growth initiative for South Africa (summary). The Presidency, SA Government, 1–19.

- Bhagwati, J, 1958. Immiserizing growth: A geometrical note. The Review of Economic Studies 25(3), 201–5. doi: 10.2307/2295990

- Bhorat, H, Naidir, K & Pillay, K, 2016. Growth, poverty and inequality interactions in Africa: An overview of key issues. Working Paper Series, United Nations Development Programme, New York.

- Bruhn, M & Love, I, 2014. The real impact of improved access to finance: Evidence from Mexico. The Journal of Finance 69(3), 1347–76. doi: 10.1111/jofi.12091

- Costanza, R, Hart, M, Posner, S & Talberth, J, 2009. Beyond GDP: The need for new measures of progress. The Pardee Papers 4, 1–35.

- Daly, H, 1987. The economic growth debate: What some economists have learned but many have not. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 14, 323–36. doi: 10.1016/0095-0696(87)90025-8

- Demetriades, P & Hussein, K, 1996. Does financial development cause economic growth? Time-series evidence from 16 countries. Journal of Development Economics 51(2), 387–411. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(96)00421-X

- Demirguc-Kunt, A, Klapper, L & Singer, D, 2017. Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: A review of recent empirical evidence. World Bank Working Paper 8040, 1–25.

- Dierckxsens, W, 2000. The limits of capitalism: An approach to globalisation without neoliberalism. Zed Books, New York.

- Enisan, A & Akinlo, O, 2007. Financial development, money, public expenditure and national income in Nigeria. Journal of Social and Economic Development 9(1), 10–28.

- Fourie, F, 2014. How inclusive is economic growth in South Africa? Econ3, 3 September, 1–8.

- Ikhide, S, 2015. The finance and growth debate in Africa: What role for financial inclusion? African Banking and Finance 5, 1–22.

- ILO (International Labour Organisation), 2012. Youth employment interventions in Africa. ILO, Ethiopia.

- Klasen, S, 2010. Measuring and monitoring inclusive growth: Multiple definitions, open questions, and some constructive proposals. Sustainable Development Working Paper 12, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

- Kubiszewski, I, Costanza, R, Franco, C, Lawn, P & Talberth, J, 2013. Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress. Ecological Economics 93, 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.04.019

- Lorek, S & Spangenberg, J, 2013. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy – beyond green growth and green economies. Journal of Cleaner Production 1(12), 1–12.

- Ncube, M, 2015. Inclusive growth in Africa. In Monga, C & Lin, J (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Africa and economics: Volume 1. Oxford University Press, London.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2014. Report on the OECD framework for inclusive growth. OECD, Paris.

- Pouw, N & McGregor, A, 2014. An economics of wellbeing: What would economics look like if it were focused on human wellbeing? IDS Working Paper 436, 1–25.

- Ramos, R, Ranieri, R & Lammens, J, 2013. Mapping inclusive growth. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth Working Paper 105, 1–18.

- Ray, T & Liew, K, 2003. Society and civilization: An optimization algorithm based on the simulation of social behavior. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 7(4), 386–96. doi: 10.1109/TEVC.2003.814902

- Stiglitz, J, Sen, A & Fitoussi, J, 2009. Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. French Government 10, 1–292.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), 2016. Human development report 2016: Human development for everyone. UNDP, New York.

- Vasudev, S, 2013. Inclusive economics enabled by inner engineering. Isha Foundation, Davos.

- Verstappen, S, 2011. The Bellagio initiative online consultation: The inclusive economy. The Broker, November, 1–8.

- World Bank, 2016. World development indicators 2016: Featuring the sustainable development goals. World Bank, Washington.

- World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987. Our common future. Oxford University Press, New York.