ABSTRACT

The ineffectiveness of enterprise policy in some southern Africa’s rural areas has led to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) attempting to increase their political influence by engaging in the enterprise policy process. This paper examines the case of one NGO from one of the poorest southern African countries – Zimbabwe – in order to bring insights to its role as policy influencer in the regional approaches of enterprise policy-making. The paper argues that an understanding of such role requires the appreciation of how people and organisations are embedded to their contexts. The evidence suggests that in the case study the NGO’s role is only modest.

1. Introduction

For a long time, enterprise policy has been one of the most praised public policies in both developed and developing countries. Broadly, it has been assumed that enterprise policy could help to stimulate innovation, create employment and generate economic growth by supporting the creation and consolidation of new and small businesses (Audretsch, Citation2004; Dennis, Citation2011; Guerrero et al. Citation2011; Lundström & Stevenson, Citation2005; Urbano et al. Citation2010a, Citation2010b). In less developed economies, enterprise policy has also been portrayed as an appropriate tool to solve their chronic poverty problems (Goedhuys & Calza, Citation2016; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Obeng & Blundel, Citation2015). However, over the past years, increasing scepticism has grown in light of the weak and ambiguous results accomplished. A recent research stream, framed in what may be called critical approaches to enterprise policy, is providing new insights that invalidate the mythical perception of enterprise policy as the panacea to meet economic and social challenges (Acs et al., Citation2016; Shane, Citation2009; Wapshott & Mallett, Citation2018). It has also been critiqued that enterprise policies have tended to be centralised, so that many government interventions are found ineffective at sub-national levels (Fotopoulos & Storey, Citation2019; Huggins et al., Citation2015; Xheneti, Citation2017). One of the main effects of such scholarship is the correspondingly greater concern for analysing the enterprise policy process from the perspective of the contextual actors who intervene in the process (Arshed, Citation2017; Bridge, Citation2010; Smallbone, Citation2016). Yet, limited attention has been paid to NGOs’ influencer role in enterprise policy-making processes, despite that they have been widely recognised as a dynamic force on public policy-making (Abednico, Citation2015; Bebbington, Citation2004; Chigudu, Citation2015; Klugman, Citation2000).

The objective of this article is to fill part of this void in the literature. Based on a longitudinal case study, we examine how one of the largest NGOs in Zimbabwe works to influence the approaches of enterprise policy in favour of disadvantaged rural areas. Zimbabwe currently has one of the lowest incomes of the southern African countries,Footnote1 and a remarkable history of failures in enterprise policy (Bomani et al., Citation2015). Its policy interventions have tended to be partisan, temperamental, exclusionary, hurried, and short-term bent, while a certain ambiguity has prevailed in the state and NGOs relationships (Zhou & Hardlife, Citation2012). Thus, within the southern African context, the Zimbabwean experience makes the issue sharper. While the research is premised on grounded-theory (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1997), a framework based on the notion of embeddedness (Granovetter, Citation1985; Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990) is used to enrich the interpretations concerning the contextual factors that affect NGOs’ strategies to influence enterprise policy-making.

The article seeks to contribute to the existing literature in several ways. First, it extends recent work on the enterprise policy process by considering how one of its possible stakeholders – an NGO – works to influence enterprise policy for the benefit of poor rural regions. Second, by using an embeddedness approach it provides insights on the dynamic interplay that NGOs can bring between the enterprise policy-making and the socio-cultural processes that work in-context. Thirdly, by approaching a reality of Zimbabwe, it contributes to filling the gap that exists in the literature concerning what happens in rural regions from the complex and unstable African continent, providing evidence with implications for wider enterprise policy.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. It first summarises the theoretical background and conceptual framework that underpins the investigation by presenting the current understanding of enterprise policy-making, the main features of southern African NGOs as stakeholders of enterprise policy, and the embeddedness approach. The paper then moves on to discuss the research design and then the context of the study. The following section presents and analyses the findings, while the paper concludes by highlighting the major outcomes and implications of the work.

2. Theoretical background and conceptual framework

2.1. The enterprise policy process in-context

Enterprise policy usually includes a variety of governmental interventions aimed at affecting new, small, and entrepreneurial business (Dennis, Citation2011; Lundström & Stevenson, Citation2005). Enterprise policy making is deemed necessary where small businesses are vulnerable to market failures or the level of new business creation is low in a particular area (Goedhuys & Calza, Citation2016; Smallbone, Citation2016; Smallbone & Welter, Citation2001). However, in practice, the implementation of many enterprise policies has been driven not so much from local needs as from international politics (Xheneti, Citation2017). This has led to a dissociation of the measures implemented from the context in which they are performed and often to poorer results than expected (Arshed et al., Citation2017; Chigudu, Citation2015; Huggins et al., Citation2015). The so-called entrepreneurial ecosystem approach (Stam, Citation2015; Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018) is providing a new framework to respond to this concern.

A distinctive feature of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach is the appreciation of the context as an endogenous part of the enterprise policy process. Beyond variations in the level of entrepreneurship or the vulnerability of local SMEs, other varieties on spatial variables, such as the way in which people are committed to the places, are seen as relevant (Grillitsch, Citation2019; Stam, Citation2015). Indeed, a significant distinction from previous enterprise policies is the importance attributed to the entrepreneur – or potential entrepreneur – over the business. Policies focused on enhancing entrepreneurial ecosystems perceive the entrepreneur not as a result of the enterprise policy but as a central player (Stam, Citation2015). Another difference lies in the importance given to the social dimension of the context, which has turned to be one of the policy’s focal points (Mason & Brown, Citation2014; Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018). Thus, it might be said that, on the one hand, the political approach to fostering entrepreneurship and SMEs has been socialised by recognising the interdependence between social and economic forces as they appear in a place. On the other hand, it might also be stated that such political approach has been micro-regionalised, in the sense that it acknowledges the importance of a micro-regional architecture on the world of enterprise policy premised on a wide diversity of social, spatial and historical circumstances – e.g. economy, ethnicity, religion, culture.

With the recent literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems, the debates concerning enterprise policy formulation and the enterprise policy process have been re-nurtured. A generally accepted disaggregation distinguishes four main stages: agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation and monitoring, and evaluation of policy (Birkland, Citation2016). But the current concern is very much on how contextual aspects and actors are involved throughout the different stages of the enterprise policy process (Huggins et al., Citation2015). In other words, the challenge is to know how places and people are credited (or not) with influence on government policies.

The emphasis on community participation and local decision making is one of the main features of the so-called bottom-up approach (Panda, Citation2007). In the context of enterprise policy, this means to advocate enterprise policy processes that enable the involvement of local people ─ e.g. entrepreneurs ─ and allow regional and local flexibility (Huggins et al., Citation2015). The bottom-up approach is in opposition to the traditional top-down approach, which has been mainly focused on the exclusive involvement of trans(national) government policy makers (Huggins et al., Citation2015). Such participation of external actors has been especially compelling in the African continent, where international policies have been guiding domestic policies, yet often using conceptual frameworks that do not reflect the cultural realities of the policy’s beneficiaries, nor the high levels of political corruption among many policy-makers (Zhou & Hardlife, Citation2012). Local African NGOs, however, can also make use of interventions that theoretically may be well understood as top-down approaches. This occurs when they try to participate in lobbying and bargaining with decision-making authorities at local platforms (Panda, Citation2007). In fact, at times, African NGOs mix approaches in their own context, so that they can succeed in their goal of taking greater responsibility in the public policy processes and facilitate the participatory decision-making ─ including community participation. The next section discusses these issues.

2.2. Understanding southern African NGOs in the framework of the enterprise policy process

From the 1990s on, the number and influence of NGOs have been growing in southern Africa. NGOs have emerged in many shapes and forms, but there are also some typical features. For example, Klugman (Citation2000), in her study about NGOs from South Africa, has highlighted their voluntary formation, relative independence – in the sense that they work independent of government, but many depend on international donors’ funds for their survival – and development orientation. In fact, while NGOs can deploy multiple approaches to achieve their objectives, a great part of their popularity was fuelled as they began to be perceived as appropriate organisations to dealing with development problems in better ways than governments (Bebbington, Citation2004; Fowler, Citation2000). In this context, a typical trend has been their rise to the political stage premised on the belief that the participation of NGOs is essential to the policy making that wants to guarantee the rights of those marginalised (Dorman, Citation2001; Van Welie & Romijn, Citation2018).

Nowadays, in southern Africa, there are a number of NGOs whose purpose mainly focuses on influencing enterprise policy (Dorman, Citation2001; Klugman, Citation2000 Nyoh, Citation2019; Tirivanhu et al., Citation2015). The seeking of NGOs to having a part in the enterprise policy process is in addition to their traditional role in seeking poverty alleviation, especially in rural and depressed regions (Abraham, Citation2019; Bornstein, Citation2003; Dorman, Citation2001; Kalu, Citation2016; Söderbaum, Citation2007). In fact, it has been recognised that NGOs’ interventions can contribute to transforming certain neglected areas traditionally considered as passive recipients into active micro-regions able of articulating specific interests (Millsten, Citation2015; Söderbaum, Citation2007; Unruh, Citation2015).

The rising political influence of NGOs, however, is not a guarantee of an improvement in public governance, especially when it is dominated by authoritarian rules or quasi-democratic regimes as it occurs in many southern African countries (Bornstein, Citation2003; Pilossof, Citation2012; Van Driel & Van Haren, Citation2003). Nonetheless, the differences within southern Africa ─ some countries such as Botswana or South Africa are relatively stable and with multiparty democracies, while others such as Zimbabwe are living a period of important political change ─ affect the extent to which governments interact with NGOs as well as the NGOs’ organisational culture. So, within southern Africa it is possible to find NGOs working in partnership with the state, in supporting or in a reforming role (Abdenico, Citation2015; Mutongwizo, Citation2018). This is important because it implies different freedoms of expression for NGOs as a means of promoting interventions at distinct levels. Moreover, even though an NGO involvement may be a remarkable feature in some stages of policy process, it could be hampered by governments and, therefore, may have little policy impact (Klugman, Citation2000). Still, the fact that there are opportunities for NGOs to participate in policy-making does not mean that NGOs are always capable of playing an influencer role, nor to play it appropriately in benefit of local areas’ development. Besides NGOs should not be idealised, since they may also be seduced by personal interests and may end up losing the collective will to influence politics to the benefit of society (Abdenico, Citation2015; Smith, Citation2010; Toledano & Karanda, Citation2015, Citation2017).

Overall, southern African NGOs’ interventions in enterprise policy making cannot be completely understood without a basic appreciation of the social structures and cultures upon which their inhabitants live, and the NGOs are modelled (Karanda & Toledano, Citation2018b). Yet the ideas of contextuality draw on the concept of embeddedness (Granovetter, Citation1985; Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990), which has been acknowledged as appropriate to addressing economic relationships in a wider context of on-going historical and social relations. Our approach to it is inevitably connected to what has been acknowledged to the wider field of sociology and its application to the entrepreneurship field. To this we turn now.

2.3. The embeddedness approach

Karl Polanyi (1886–1964) is generally acknowledged as the originator of the concept of embeddedness (Dacin et al., Citation1999; Granovetter, Citation1985; Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990), which he employed to describe the social structure of modern markets (Uzzi, Citation1997). However, the sociologist Mark Granovetter’s (Citation1985) classic essay has served as a more proximate and accessible stimulus for modern research on embeddedness and its application to the entrepreneurship field (Dacin et al., Citation1999).

Granovetter (Citation1985) presents the argument of embeddedness by placing economic relationships in a wider context of on-going social relations. From his perspective, embeddedness emphasises the importance of the social structures in shaping economic activities. In Granovetter’s (Citation1985) terminology, this situation is described by the notion of structural embeddedness, which can work as both stimulus and constraint of economic decisions and actions. Following Granovetter’s (Citation1985) reasoning, the entrepreneurial activity is understood as a network of relationships (Jack & Anderson, Citation2002) and entrepreneurs as part of the local structure (Gaddefors & Cronsell, Citation2009; Jack & Anderson, Citation2002). Thus, if such structures enhance entrepreneurial behaviours, entrepreneurial activities would be expected to occur naturally.

Economic decisions can also be shaped by other contextual dynamics. Zukin & DiMaggio (Citation1990), for example, refer to cultural and political embeddedness. Cultural embeddedness has to do with the manner in which economic decisions are shaped by shared collective understandings (Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990). It has a cognitive function, in the sense that it serves as a channel to providing information, influence perception and the ends that people pursue. But it also implies affective and valuative aspects. In addition, as it occurred with structural embeddedness, diverse forms of culture – e.g. categories, values, beliefs, informal norms – may enable or restrict any economic activity (Dequech, Citation2003). Political embeddedness is often referred to as the rules and regulations that form the framework within which local actors interact; but because political institutions have an ideological dimension, political embeddedness may also shape social values that are embodied in such rules (Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990). Indeed, different dimensions of embeddedness usually overlap and interact simultaneously to shape standards of behaviours, economies, and organisational forms and strategies (Dacin et al., Citation1999).

Literature referring to contexts with high entrepreneurial activity has shown the importance of embedding to the entrepreneur (Jack & Anderson, Citation2002; Korsgaard, Ferguson, & Gaddefors, Citation2015). Some advantages are related to recognising opportunities and obtaining information, knowledge, and financial resources through exchanges based on trust and reciprocity instead of being based on rigid and impersonal markets. However, in areas in which there is lack of entrepreneurial activity, being embedded is often interpreted negatively because it might discourage any different behaviour such might be, in that context, an entrepreneurial behaviour (Karanda & Toledano, Citation2012; Seelos et al., Citation2011).

According to the embedded perspective, the influence of NGOs in enterprise policy will depend, in part, on the way in which people and institutions are embedded to their places. The consideration of embeddedness thus, seems to be important for NGOs that are trying to promote entrepreneurial activities in specific regions and influence the enterprise policy process.

3. Research design

This research used the case study method (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Yin, Citation2009) to address the question of ‘to what extent and how NGOs do perform their role as influencers of enterprise policy-making in the context of Zimbabwe’. Adopting an exploratory qualitative approach, we narrowed the study to investigate in-depth the case of one NGO from Zimbabwe ─ thereafter we will refer to it as NGO-EP, non-governmental organisation for influencing enterprise policy. The single case-study design allows investigating in-depth phenomena in their real-life context, builds detailed narratives displaying the process and addresses issues where the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not obvious (Yin, Citation2009).

The selection of the case was purposive. Purposeful sampling is useful when the research is orientated towards a rather clear-cut research interest (Barglowski, Citation2018). It involves the identification of relevant cases before the research is conducted. Its logic and power lie in selecting ‘information-rich cases’ (Patton, Citation1990, p.169), that is, cases for study in depth, and from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the investigation (Patton, Citation1990). In our research, the selection of what was an ‘information-rich case’ was based on: (1) its capacity to mirror the research interest, and (2) our knowledge about the field (Barglowski, Citation2018).

Firstly, it was considered the legitimacy and experience that NGO-EP had in both lobbying social and enterprise policies in Zimbabwe (top-down approach) and promoting disadvantaged people’s participation in local projects (bottom-up approach). NGO-EP was launched in Zimbabwe in 1993, and as it has accumulated experience at implementing local development projects it has also attempted to increase its political influence by engaging in enterprise policy processes. In 2017 NGO-EP had an important number of professionals working throughout the country, which included a legal team working on policy lobbying and representation to community associations. Furthermore, in some periods, NGO-EP hires temporary workers to attend the field work required by some of its projects, and researchers to collaborate in analysis tasks. Besides, being one of the few national NGOs committed to poverty alleviation and economic development of marginalised rural communities, it provided an interesting opportunity to gain insights about its influence on enterprise policy-making on behalf of disadvantaged regions.

Secondly, purposive sampling is useful when researchers have access to information that can provide a clear image of what they aim to find out (Barglowski, Citation2018; Toledano & Anderson, Citation2017). In our research, the possibility of observing NGO-EP’s actions for more than one year was key to picking the case. This was feasible as one of the authors became part of an insider research team in the framework of one action research project carried out by the NGO from 2015 till 2017. The findings presented here, however, are circumscribed to the activities that NGO-EP accomplished during 2016 and 2017 in order to influence the enterprise policy process in Zimbabwe on behalf of rural areas from the North and West of the country.

The main data collection instruments involved interviews, participant observation and documentary material. The first author conducted participant observation during six group discussions that took place with local people from the rural areas that NGO-EP organised. Observation was also conducted during eight meetings between NGO-EP’s staff and government officers. NGO-EP’s workers and staff were interviewed several times and informal conversations were also maintained. In addition, in-depth interviews were conducted with seven government officials. Most interviews were conducted in English, but some discussions were carried out in Shona – a vernacular language spoken by both one of the researchers and some of the respondents. In sum, different units of analysis were approached through different tools as it is summarised in .

Table 1. Data collection methods and key informants.

The data were analysed inductively following the guidelines of grounded-theory (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1997). We relied on a constant comparison of multiple informants over time in order to identify conceptual patterns among the evidence (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1997). Specifically, we drew from Gioia et al.’s (Citation2013) analysis guide to transform the amount of information into insightful ideas. We reviewed the data on NGO-EP’s actions to find out its role as influencers of enterprise policy-making. This drew out significant themes that informed a coding frame (e.g. actions for influencing political agenda; actions for influencing the formulation and implementation of the enterprise policy process) and material to contrast with our conceptual framework. For this, we focused on our primary data source, the interviews with NGO-EP’s staff, because the staff themselves could provide the best insights on the involvement of NGOs in the different stages of the policy process, and on how embeddedness affected their actions. We then approached the data from our other sources and added supporting or contradicting data points to the themes. This was an important stage, as it allowed us to integrate data from our multiple sources. To take note of the observations that we considered significant in the different places where the encounters occurred was important to interpret all the data appropriately. Besides, every interpretative attempt – including translations from Shona – was made to honour the spirit, imagery and tone of all the conversations and dialogues that occurred through the interviews. Finally, consent for publishing this work was obtained, but it was also agreed to use the information of both the NGO and people interviewed anonymously.

4. Study context

The area of Zimbabwe is relatively sparsely populated (390,759 sq km where about 16.9 million people live). Despite that Zimbabwe was once considered as one of the most prosperous southern African nations, Zimbabwe’s economy has been steadily eroding to the point that it is currently one of the lowest income countries of southern Africa (Chigudu, Citation2015; Guo, Citation2020; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Matamanda, Citation2019).

Generally, rural regions are the most acutely harmed by Zimbabwe’s economic situation. This means a greater suffering for rural populations in terms of getting basic commodities, access to infrastructure, basic service provision such as electricity or clean water, and less educational and employment opportunities (Karanda & Toledano, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The main economic activity is self-subsistence agriculture and is dominated by informal activities in which most household-family members contribute in several tasks. Additionally, in the North and West of Zimbabwe – the area referred to in this study – the land is marginal to proper agricultural production, such that it cannot supply people that go beyond farmers’ families.

In terms of Zimbabwe’s government policies, the political discourse has traditionally been directed towards social sectors and the expansion of rural infrastructure; yet, the implementation has proved a major challenge (Zhou & Hardlife, Citation2012; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2018a). Over the past years, however, enterprise policy has gained importance over other economic policies as a way of influencing unemployment rates and reducing poverty through the support to new and small businesses (Bomani et al., Citation2015). A significant issue was the establishment of the Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises and Cooperative Development (SMECP) in 2002, with the objective of facilitating a conducive environment that streamlined the development of SMEs, the creation of employment and economic growth (Bomani et al., Citation2015).

Broadly, two features have been remarkable in Zimbabwe’s enterprise policy-making. On the one hand, a continuous interaction between international organisations – mainly the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) – and domestic policy imperatives. On the other hand, a clear politicisation of the enterprise policy formulation by the political party in power since Zimbabwe’s independence from Britain in 1980 – the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) – coupled with excessive bureaucratic procedures and growing authoritarian and corruptive practices. The ZANU-PF party led the country with the same president, Robert Mugabe, for 37 years.Footnote2 Yet, the enterprise policy in Zimbabwe has repeatedly failed to achieve its purposes, and the negative consequences have been especially noticed in rural regions (Karanda & Toledano, Citation2018b). Due to the fact that political power is usually concentrated in urban areas, groups favouring industrial protection have tended to have more influence on policy-makers’ decisions than those voicing rural people’s problems and interests.

5. Findings and discussion

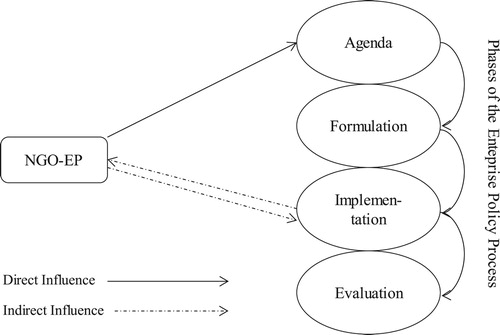

In this section, the findings are presented through a distinction between the role of NGO-EP in influencing the enterprise policy process during its inception (agenda) and its role in enterprise policy formulation and implementation. In the analysis, special emphasis is given to the conditions (embedded process) under which NGO-EP has worked to influence enterprise policy.

5.1. Influencing the agenda of the enterprise policy process

Recent literature suggests that the participation of NGOs in policy-making processes is increasingly recognised within the African continent (Abraham, Citation2019; Dorman, Citation2001; Kalu, Citation2016; Klugman, Citation2000; Nyoh, Citation2019; Obeng & Blundel, Citation2015; Tirivanhu et al., Citation2015). Our findings confirm the literature when ‘participation’ is understood from the perspective of bringing new concerns into the enterprise policy agenda. Indeed, it is not uncommon that the NGO presents proposals that policy-makers value as attractive and ‘friendly’ enough to include.

The case study’s evidence shows that in two prominent themes it was possible for NGO-EP to create space in the enterprise policy-making agenda.Footnote3 Concretely, in a first proposal, NGO-EP advocated for supporting informal ways that people were using to help acquaintances in their informal activities as small-scale individual entrepreneurs. This implied to assist not only entrepreneurs but also people who were informally supporting local entrepreneurial activity through small personal loans, teaching some craft techniques, or selling some products. NGO-EP’s second proposal had to do with entrepreneurship education among rural population. Specifically, it was suggested to offer one-on-one counselling and group educational sessions targeted at young rural people using the informal apprenticeship model ─ an old traditional Zimbabwean’s approach.

It is notable that both proposals put special emphasis on strengthening the resources and capacities already in place in the rural areas. Furthermore, they implied to support business development services that could benefit most of the working-age population. In this sense, the NGO-EP’s proposals supported in many ways the view of the recent entrepreneurial ecosystem approach that points towards a policy for an entrepreneurial economy instead of a narrow entrepreneurship policy (Mason & Brown, Citation2014; Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018; Stam, Citation2015). The words of one of the NGO-EP’s staff interviewed were clearly supportive of this idea:

We try to involve rural people in their own development and that is why we try to present their problems as one unique target group (…) is like imagining different people embodying different roles in terms of entrepreneurial activities (…) when you give them opportunities to take responsibilities, something great happens. (interview 1, NGO-EP’s staff, Rushinga, 3 November 2016)

Additionally, from the perspective of the embeddedness theory (Granovetter, Citation1985), NGO-EP’s proposals provided a very strong fit with the significance of social networks and cultural history for entrepreneurial activities (Krosgaard et al., Citation2015), mirrored in the framework of designing proper support measures. Some connections between NGO-EP’s proposals and the vision espoused in social and cultural embeddedness (Granovetter, Citation1985; Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990) were identified. With the first proposal, NGO-EP proved to be very aware of rural people being embedded in place through social bonds with their extended families and neighbours. The proposal itself showed a discourse of solidarity based on the social cohesion among rural people as an essential justification for governmental support. The second proposal was very much premised on a cultural appreciation and understanding of the value that rural people gave to their education. While Zimbabwe has boasted of high rates of educated people compared to other southern African countries (Chigudu, Citation2015; Karanda & Toledano, Citation2018a, Citation2018b), it became clear that some rural people had suffered from lower educational opportunities than their urban counterparts. In this sense, any proposal that supported their education showed a great empathy with one of the aspects that rural inhabitants most valued. Therefore, at first, the fact of paying attention to how people are socially and culturally embedded to their places may positively influence in the articulation of proposals that gain acceptance within enterprise policy agendas.

On the other hand, we observed that informal channels were more effective for NGO-EP to access national government departments than formal ones. In fact, there was access to legislators through lobbying. Informally, NGO-EP’s staff primary contacted with government officials of the rural districts, and then the officials made it possible for the meetings at a central level. As one of NGO-EP’s workers stated: ‘we always seek to cultivate friendly relations with the political administrators (…) at the end of the day, if they are not with us, we will never get any help’ (interview 14, NGO-EP’s worker, Harare, 28 February 2017). Moreover, from the political discourse it could be deduced that government officials wanted to be friendly and collaborate with NGOs.

In sum, NGO-EP was able to articulate a pluralistic array of issues, and to frame them in terms of entrepreneurial needs as policy proposals that had the possibility of gaining some support from national government. This became manifested by including two proposals in the enterprise policy agenda.

5.2. Influencing the formulation and implementation of the enterprise policy process

Some scholars have noted that the involvement of NGOs in some stages of a policy process does not imply that they achieve a political impact (e.g. Kalu, Citation2016; Klugman, Citation2000; Nyoh, Citation2019). Our case study sharply confirms this appreciation. Although NGO-EP exhibited some fruitful results in terms of influencing the enterprise policy agenda, this was not the case when it came to forming part of the political process at the formulation phase. In fact, after the political agenda, there was no hard distinction among stages in the enterprise policy process as it is suggested in literature (Birkland, Citation2016). Instead, our evidence showed subtle borders between phases and a messy procedure.

Interviews with government officials revealed their concern for the NGO-EP’s proposals in terms of mobilising the resources required. From their perspective, such proposals were particularly complex to implement due to the lack of resources of SMECP department. Because of this reason, they considered it pointless to continue regarding them in the enterprise policy-making.

From NGO-EP’s side, however, the government’s negative response was interpreted differently. The general view pointed towards the existence of corruptive practices within Zimbabwe’s authoritarian politician’s regime as the main reason for rejecting the inclusion of NGO-EP’s proposals in further stages of the enterprise policy process. This perception reinforces research on policy process within southern Africa (Borsntein, Citation2003; Zhou & Hardlife, Citation2012), and particularly in the context of Zimbabwe’s corruptive policy practices (Pilossof, Citation2012). Concretely, one of NGO-EP’s workers complained by saying: ‘the formulation of public policies in Zimbabwe is led by the selfish desires of political elites who only seek how to perpetuate their positions and interests ahead of general others’ (interview 2, NGO-EP’s worker, Harare, 11 May 2017). Another NGO-EP’s worker criticised: ‘the formulation of enterprise policy is still a government monopoly where other interested parties such as us have normally little to do’ (interview 5, NGO-EP’s worker, Harare, 11 May 2017). Other comments were similarly plain and, in general, denounced government abuses in enterprise policy formulation. They suggested that the enterprise policy formulation followed the rule of choosing the most promising alternative by considering which would be the most favourable political result.

However, while interviews with key informants provided different perspectives of the situation, from our observations it became clearer that the ability of policy makers to negotiate was quite superior to the ability of NGO-EP’s staff. So, even though NGO-EP had a policy formation office, there seemed to be a certain weakness in this area. One of the NGO’s workers, referring to policy makers’ discourses also recognised that, ‘they know how to say all the right things, but then they will never do what they say’ (interview 11, NGO-EP’s worker, Harare, 20 June 2017).

Such capacity to negotiate by the government officials was even clearer when considering the implementation of enterprise policies. Paradoxically, there was a relatively high degree of involvement of NGO-EP in the enterprise policy implementation stage as a result of accepting the government officials’ propositions – yet, different from initial NGO-EP’s proposals. It seemed that, at some point, the government had recognised that NGO-EP may help to reduce the economic burden of providing enterprises’ support services on a regional and local basis. At best, government officials encouraged NGO-EP to serve as partners in delivering some SMEs support in regions and communities that they otherwise may not reach out to. In this respect, there was no common view among NGO-EP’s workers and staff. Some of the workers grumbled that they would end up doing additional work and often in vain. NGO-EP’s staff, in contrast, seemed to be more prone to working with the government officials and indeed, appeared to maintain friendly relationships with them. Interviews with some staff revealed that their positive view was partly based on what might be the positive repercussions for the regions. As one of them asserted, ‘it may be good for the region (… .) we may be empowering rural people, despite that we would rather do it with other means’ (interview 2, NGO-EP’s staff, Watyoka-Mondoro, 4 September 2017). But also, they held this alternative as a means for increasing their influence in future political processes. As one of the staff members interviewed noted, ‘in Zimbabwe it is well known that much of the policy has been a case of implement first, formulate and regulate later’ (interview 3, NGO-EP’s staff, Watyoka-Mondoro, 4 September 2017). Thus, it is in this context that we may affirm that NGO-EP was exerting some influence in the implementation of micro-regional approaches of Zimbabwe enterprise policy. Yet, such influence only implied, at least officially and in the short-term, non-controversial issues and interventions at technical level, and never a participation in evaluation tasks (see ).

Finally, from an embedded perspective (Granovetter, Citation1985), it may be affirmed that NGO-EP’s influence in enterprise policy formulation and implementation was constrained by the strong political embeddedness (Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990) that prevails in Zimbabwe. Such political embeddedness seemed to be characterised by being geared towards market and personal enrichment rather than social welfare logic. As the case-study’s evidence has shown, government representatives always tried to pull back from NGO-EP’s direct involvement in enterprise policy processes, especially in the stages of formulation and implementation.

6. Conclusions

The enterprise policy processes, along with the role that the context and their stakeholders may play in such processes, are becoming relevant parts of the contemporary enterprise policy literature (Arshed, Citation2017; Smallbone, Citation2016; Stam, Citation2015). This paper has presented the case of one NGO from one of the poorest southern African countries – Zimbabwe – in order to bring insights on its role as a policy influencer of enterprise policy. From the case-study’s evidence two roles deserve to be stressed. First, by providing alternatives to policy makers that emphasises the embeddedness of people to their context, NGO-EP was advocating in support of an entrepreneurial rural economy, in which the social and cultural aspects of the regions become as important as the economic one. Second, through a selective collaboration with Zimbabwe’s policy makers in the implementation of governmental policies, NGO-EP was called to enhance entrepreneurship among rural people; however, it was doing it through the execution of enterprise policy-makers’ initiatives. The case shows that while NGO’s proposals found room in enterprise policy agenda, they were only mentioned rhetorically but excluded from enterprise policy formulation or implementation instruments. Therefore, in our case-study, we identify the well-known ‘non-profit failure’ (Klugman, Citation2000) when the NGO lacks the necessary resource or enforcement mechanisms to negotiate with policymakers at high levels. Consequently, the role of NGO-EP in influencing enterprise policy can only be defined as modest.

In conclusion, taking the experience of NGO-EP as evidence, we affirm that the enterprise policy process in Zimbabwe during the study period remained state-centred and exclusionary both in terms of participants in the process and in the regional approach adopted by the government. This leads us to two other ideas: on the one hand, marginal rural regions are not, so far, a priority for Zimbabwe’s enterprise policies, and on the other, the enterprise policy process continues being a top-down issue. In addition, the case study also hints at the need for NGOs to consider not only the technical and managerial competencies of their staff and workers but also their political and discursive skills as an important possible determinant of policy influence. Moreover, the evidence suggests that NGOs’ alliances with local government officials may be necessary although not sufficient for influencing the enterprise policy formulation and implementation. This would require from NGOs the tactical ability to work between confrontation and co-optation, and to choose carefully the themes on which to commend or press the government.

Ultimately, this study stresses that the role of NGOs as policy influencer of the enterprise policy process cannot be understood without a basic appreciation of the embedded processes upon which both people and government are shaped. Particularly, this research has shown how important it was for NGO-EP to pay attention to the social and cultural embeddedness (Granovetter, Citation1985; Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990) in order to create a positive synergy between the rural regions and NGO-EP’s actions and proposals. As a result of such synergies we found creative strategies that allowed NGO-EP to find a place in enterprise policy agenda. At the same time, the case shed light on how the political embeddedness (Zukin & DiMaggio, Citation1990) constrained in great part NGO-EP’s participation in formulation and implementation processes.

Bearing these considerations in mind, a word of caution is needed. As we have focused on a single case study, it limits a direct translation of the conclusions to other areas beyond Zimbabwe. In occasions, we should also be cautious to apply the conclusions to other Zimbabwean NGOs, since they often work in complex environments with different actors embedded in different processes. Nonetheless, despite that our empirical work is based on a single case study, building such knowledge has allowed us to get an initial understanding of the challenges and opportunities that some NGOs may face when they try to influence enterprise policy process in the southern African context. Fruitful avenues of future research could entail comparative case studies that probe the influencer roles played by different NGOs in other contexts. Understanding the relationships that NGOs maintain with other policy influencers within a region – such as donors, think tanks, or opposition political parties – might also be other interesting fields to build insights and seek ways to link with broader discussions in enterprise policy research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Broadly, Southern Africa includes the countries of Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Some institutions, however, can take a wider classification.

2 An emergency situation was declared on 14 November 2017, when the army took over the city of Harare with the objective of removing the president. Such goal was peacefully achieved one week later, on 21 November. On 30 July 2018 Zimbabwe celebrated democratic elections with the involvement of international observers. The ZANU-PF political party won that elections and remains in power so far.

3 Throughout the time of the empirical research, there were other proposals raised by NGO-EP, but they never made any influence on the enterprise policy process, so they are ignored in this paper.

References

- Abednico, S, 2015. Rural communities and policy participation: The case of economic policies in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Social Work 5(2), 87–107.

- Abraham, KKA, 2019. The role and activities of policy institutes for participatory governance in Ghana. In H Grimm (Ed.), Public policy research in the Global South. A cross-country perspective (pp. 151–170). Springer, Cham.

- Acs, Z, Åstebro, T, Audretsch, D & Robinson, DT, 2016. Public policy to promote entrepreneurship: A call to arms. Small Business Economics 47(1), 35–51.

- Arshed, N, 2017. The origins of policy ideas: The importance of think tanks in the enterprise policy process in the UK. Journal of Business Research 71, 74–83.

- Audretsch, DB, 2004. Sustaining innovation and growth: Public policy support for entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation 11(3), 167–191.

- Barglowski, K, 2018. Where, what and whom to study? Principles, guidelines and empirical examples of case selection and sampling in migration research. In R Zapata-Barrero & E Yalaz (Eds.), Qualitative research in European Migration studies (pp. 151–168). Springer, Cham.

- Bebbington, A, 2004. NGOs and uneven development: Geographies of development intervention. Progress in Human Geography 28(6), 725–745.

- Birkland, TA, 2016. An introduction to the policy process: Theories, concepts, and models of public policy making. 4th edn. Taylor & Francis, New York.

- Bomani, M, Fields, Z & Derera, E, 2015. Historical overview of small and medium enterprise policies in Zimbabwe. Journal of Social Science 45(2), 113–129.

- Bornstein, E, 2003. The spirit of development. Protestant NGOs, Morality, and economics in Zimbabwe. Routledge, New York.

- Bridge, S, 2010. Rethinking enterprise policy: Can failure trigger new understanding? Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Chigudu, D, 2015. Navigating policy implementation gaps in Africa: The case of Zimbabwe. Risk Governance and Control: Financial Markets and Institutions 5(3), 7–14.

- Dacin, MT, Ventresca, MJ & Beal, BD, 1999. The embeddedness of organizations: Dialogue & directions. Journal of Management 25(3), 317–356.

- Dennis Jr, WJ, 2011. Entrepreneurship, small business and public policy levers. Journal of Small Business Management 49(2), 149–162.

- Dequech, D, 2003. Cognitive and cultural embeddedness: Combining institutional economics and economic sociology. Journal of Economic Issues 37(2), 461–470.

- Dorman, SR, 2001. Inclusion and exclusion: NGOs and politics in Zimbabwe. Doctoral dissertation. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:99281b24-8104-4699-8e4c-0cdc2a2c716e/download_file?file_format=pdf&safe_filename=Sara%2BDorman%2BDPhil%2Bthesis%2B-%2Bwith%2Bfigures%2Bremoved%2Bfor%2Bcopyright%2Breasons&type_of_work=Thesis.

- Eisenhardt, KM & Graebner, ME, 2007. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. The Academy of Management Journal 50(1), 25–32.

- Fotopoulos, G & Storey, DJ, 2019. Public policies to enhance regional entrepreneurship: Another programme failing to deliver? Small Business Economics 53(1), 189–209.

- Fowler, A, 2000. NGO futures: Beyond aid: NGDO values and the fourth position. Third World Quarterly 21(4), 589–603.

- Gaddefors, J & Cronsell, N, 2009. Returnees and local stakeholders. Co-producing the entrepreneurial region. European Planning Studies 17(8), 1191–1203.

- Gioia, DA, Corley, KG & Hamilton, AL, 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods 16(1), 15–31.

- Goedhuys, M & Calza, E, 2016. Addressing entrepreneurial heterogeneity in developing countries: Designing policies for growth and inclusive development. In CC Willians & A Gurtoo (Eds.), Routledge handbook of entrepreneurship in developing economies (pp. 549–566). Routledge, New York.

- Granovetter, M, 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91(3), 481–510.

- Grillitsch, M, 2019. Following or breaking regional development paths: On the role and capability of the innovative entrepreneur. Regional Studies 53(5), 681–691.

- Guerrero, M, Toledano, N & Urbano, D, 2011. Entrepreneurial universities and support mechanisms: A Spanish case study. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 13(2), 144–160.

- Guo, Q, 2020. Can Zimbabwe be saved from the brink of collapse? Journal of Contemporary Educational Research 4(1), 13–14. doi: 10.1002/pa.1903

- Huggins, R, Morgan, B & Williams, N, 2015. Regional entrepreneurship and the evolution of public policy and governance: Evidence from three regions. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 22(3), 473–511.

- Jack, SL & Anderson, AR, 2002. The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing 17(5), 467–487.

- Kalu, KA, 2016. Agenda setting and public policy in Africa. Routledge, London.

- Karanda, C & Toledano, N, 2012. Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: A different narrative for a different context. Social Enterprise Journal 8(3), 201–215.

- Karanda, C & Toledano, N, 2018a. Foreign aid versus support to social entrepreneurs: Reviewing the way of fighting poverty in Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa 35(4), 480–496.

- Karanda, C & Toledano, N, 2018b. The promotion of ethical entrepreneurship in the Third world: Exploring realities and complexities from an embedded perspective. Business Horizons 61(6), 881–890.

- Klugman, B, 2000. The role of NGOs as agents of change. Development Dialogue 1(2), 95–120.

- Korsgaard, S, Ferguson, R & Gaddefors, J, 2015. The best of both worlds: How rural entrepreneurs use placial embeddedness and strategic networks to create opportunities. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 27(9/10), 574–598.

- Lundström, A & Stevenson, LA, 2005. Entrepreneurship policy: Theory and practice. Springer, Berlin.

- Mason, C & Brown, R, 2014. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Paris. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Entrepreneurial-ecosystems.pdf Accessed 8 December 2018.

- Matamanda, AR, Chirisa, I, Dzvimbo, MA & Chinozvina, QL, 2019. The political economy of Zimbabwean urban informality since 2000–A contemporary governance dilemma. Development Southern Africa, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2019.1698410

- Millsten, M, 2015. Regionalising African civil societies: Lessons, opportunities and constraints. The Nordic Africa Institute. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:790494/FULLTEXT02. Accessed 27 August 2018.

- Mutongwizo, T, 2018. Comparing NGO Resilience and “structures of opportunity” in South Africa and Zimbabwe (2010-2013). Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 29(2), 373–387.

- Nyoh, IB, 2019. How multinational civil society organisations and non-governmental organisations lobby policy for human rights in Africa. Journal of Public Affairs. doi: 10.1002/pa.1903

- Obeng, BA & Blundel, RK, 2015. Evaluating enterprise policy interventions in Africa: A critical review of Ghanaian small business support services. Journal of Small Business Management 53(2), 416–435.

- Panda, B, 2007. Top down or bottom up? A study of grassroots NGOs’ approach. Journal of Health Management 9(2), 257–273.

- Patton, MQ, 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage, Newbury Park.

- Pilossof, R, 2012. A predictable tragedy: Robert Mugabe and the collapse of Zimbabwe. African Historical Review 44(1), 143–144.

- Seelos, C, Mair, J, Battilana, J & Tina Dacin, M, 2011. The embeddedness of social entrepreneurship: Understanding variation across local communities. In C Marquis, M Lounsbury & R Greenwood (Eds.), Research in the sociology of organizations. Communities and organizations (pp. 333–363).

- Shane, S, 2009. Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is a bad policy. Small Business Economic 33(2), 141–149.

- Smallbone, D & Welter, F, 2001. The role of government in SME development in transition economies. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 19(4), 63–77.

- Smallbone, D, 2016. Entrepreneurship policy: Issues and challenges. Small Enterprise Research 23(3), 201–218.

- Smith, DJ, 2010. Corruption, NGOs, and development in Nigeria. Third World Quarterly 31(2), 243–258.

- Söderbaum, F, 2007. Regionalisation and civil society: The case of southern Africa. New Political Economy 12(3), 319–337.

- Spigel, B & Harrison, R, 2018. Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 12(1), 151–168.

- Stam, E, 2015. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies 23(9), 1759–1769.

- Strauuss, A & Corbin, JM, 1997. Grounded theory in practice. Sage, London.

- Tirivanhu, P, Matondi, PB & Groenewald, I, 2015. Comprehensive community initiative: Evaluation of a transformation system Mhakwe community in Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa 32(6), 785–800.

- Toledano, N & Anderson, AR, 2017. Theoretical reflections on narrative in action research. Action Research, doi: 10.1177/1476750317748439

- Toledano, N & Karanda, C, 2015. Virtuous entrepreneurs: A rethinking of the way to create relational trust in a global economy. International Journal of Business and Globalisation 14(1), 9–20.

- Toledano, N & Karanda, C, 2017. Morality, religious writings, and entrepreneurship education: An integrative proposal using the example of Christian narratives. Journal of Moral Education 46(2), 195–211.

- Unruh, JD, 2015. Micro-regionalism in Africa: Dynamics, opportunities and challenges. In K Hanson (Ed.), Contemporary regional development in Africa (pp. 71–94). Ashgate Publishing, London.

- Urbano, D, Toledano, N & Soriano, DR, 2010a. Analyzing social entrepreneurship from an institutional perspective: Evidence from Spain. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1(1), 54–69.

- Urbano, D, Toledano, N & Ribeiro, D, 2010b. Support policy for the tourism business: A comparative case study in Spain. The Service Industries Journal 30(1), 119–131.

- Uzzi, B, 1997. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly 42(1), 35–67.

- Van Driel, F & Van Haren, J, 2003. Whose interests are at stake? Civil society and NGOs in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 20(4), 529–543.

- Van Welie, MJ & Romijn, HA, 2018. NGOs fostering transitions towards sustainable urban sanitation in low-income countries: Insights from transition management and development studies. Environmental Science & Policy 84, 250–260.

- Wapshott, R & Mallett, O, 2018. Small and medium-sized enterprise policy: Designed to fail? Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 36(4), 750–772.

- Xheneti, M, 2017. Contexts of enterprise policy-making–an institutional perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 29(3-4), 317–339.

- Yin, RK, 2009. Case study research: Design and methods. 4th ed. Sage, London.

- Zhou, G & Hardlife, Z, 2012. Public policy making in Zimbabwe: A three decade perspective. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2(8), 212–222.

- Zukin, S & DiMaggio, P, 1990. Structures of capital: The social organization of the economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.