?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Although the relationship between education and fertility is well established, an understanding of young women’s fertility responses to education over time is needed to enhance a critical appraisal of education elasticities of fertility. This study thus comparatively investigates education effects on fertility in Ethiopia, Rwanda and Zimbabwe. Multivariate fixed effects logistic regression and direct decomposition methods were applied to Demographic and Health Survey data between 1999 and 2011. Results showed that declines in youth fertility in Ethiopia and Rwanda were driven by decrease in fertility rates of those with primary education but in the Zimbabwe youth fertility changes were driven by those with secondary or higher educational attainment. We conclude that education elasticities of fertility are not constant but vary by country and stage of fertility transition. Countries that are more advanced in fertility transition therefore need to place focus on enhancing post-secondary education to sustain fertility transition.

1. Introduction

High fertility levels characterised by early start of child bearing in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have been proven to be drivers of rapid population growth on the sub-continent (Bongaarts, Citation2003; Bongaarts & Casterline, Citation2013; Population Reference Bureau, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). The effects of rapid population growth on development are well documented (Eloundou-Enyegue & Giroux, Citation2013; International Labour Organisation, Citation2015). Early child birth shortens the time it takes for a new born female child to start her reproductive career thereby contributing to faster population growth. To reduce population growth through delaying women’s age at first birth, it has previously been suggested that raising primary education enrolment through mass education is important (Caldwell, Citation1980). This was partially targeted, among other socioeconomic developmental aims, by the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) Number 2 which concerned universal access to primary education. Delaying the onset of childbearing by extending girls’ stay in formal education potentially reduces the total fertility rate (TFR) of a country thereby increasing the doubling period of a country’s total population. When a country has a longer doubling time for its total population, it means that the annual increase in the population does not result in unsustainable pressure on the existing resources thus providing a platform for investment in economic development. High population growth rates increase the urgency with which the government will be required to invest in social infrastructure like schools, hospitals and housing at the expense of much needed economic growth.

The effect of education on fertility levels is well documented in SSA and other continents (Edwards, Citation1996; Lloyd & Blanc, Citation1996; Akin, Citation2005; Behrman, Citation2015; Chemhaka & Odimegwu, Citation2019). However, the different fertility levels among countries from SSA can be argued to imply that fertility levels respond to population-level educational attainment and other factors with varying elasticities (Uchudi, Citation2001; Kravdal, Citation2002; Bongaarts, Citation2003; Gyimah et al. Citation2008; Bongaarts, Citation2010). The rates of increase in the average level of education can be similar between countries but the impact on fertility levels may differ (Channon & Harper, Citation2019). Similarly, the increase in average educational attainment can be associated with different fertility elasticities depending on a country’s phase in fertility transition and stage in economic development (Bongaarts, Citation2003; Colleran & Snopkowski, Citation2018). The concept of education elasticity of fertility is applied in this research to imply the amount of decrease or increase in fertility that is associated with the increase in average educational attainment of women aged from 15 to 24 years. We borrow the concept from ‘price elasticity of demand’ used in the field of economics to describe the changes in demand due to increase or decrease in the price of a good or service.

Although mass enrolment in primary education was important in initiating fertility transition in most African countries, the focus on primary education completion as a policy tool for accelerating fertility transition without commensurate focus on secondary and even post-secondary education in countries that have experienced notable fertility declines may be questioned (Gupta & Mahy, Citation2003). Nonetheless, there is little previous research evidence to back this argument especially in SSA. Considering the new global framework for development, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), this paper argues that the magnitude of the importance of education as a tool for fertility policy needs to be established particularly in countries that have had considerable fertility transition and have attained high levels of primary school enrolment. This is because early child birth no longer implies the end of educational career for girls and young adult females in several SSA countries including Zimbabwe. Consequently, universal primary education may be an inadequate policy tool for reducing youth fertility (Gupta & Mahy, Citation2003). To provide an evidence-backed basis for the above argument, this study sought to determine the extent to which education status affected changes in the levels of fertility of young women in Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe between 1999 and 2011.

The education elasticities of fertility among young women is worth understanding for different reasons. One of these reasons is the occurrence of fertility transition in a country like Zimbabwe where despite historically high literacy rates relative to other SSA countries, the decline of fertility was driven by older women above 30 years (Udjo, Citation1996). Given the evidence of stalled transition in this country over the 2005–15 period especially of marital fertility, it is important to understand the linkages between education and the fertility rates of the youth in Zimbabwe (Ndagurwa & Odimegwu, Citation2019). In the case of Ethiopia, the population more than doubled in less 30 years from 47.9 million in 1990 to 112 million in 2019 (United Nations, Citation2019). Further, during this period, peak annual population growth rate was 3.7% in the early 1990s and this has since declined to 2.6% in 2019.

Previous studies of fertility in SSA that investigated education as a determinant of fertility largely did so with respect to national fertility levels for all women and teenage fertility (Lloyd et al., Citation2000; Kravdal, Citation2002, Citation2012). In examining the effect of education on the decline of total fertility rates, Lloyd et al. (Citation2000) analysed pre-2000 DHS data and found that universal primary education enrolment, measured as 75% or higher enrolment rates, was significantly associated with decline in fertility in Zimbabwe, Kenya, Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa. In the countries that had not attained this level of mass education, fertility rates remained at pre-transitional levels (Lloyd et al., Citation2000). Using more recent DHS data, Kravdal analysed the effects of education at individual and community level on total fertility in 2002 and 2012 in selected SSA countries. In both studies, education proved to have a depressing effect on fertility levels (Kravdal, Citation2002, Citation2012). However, it cannot be determined from existing literature made up of cross-sectional studies that education drives fertility decline.

While the increase in educational attainment has been associated with lower TFRs, little is known about effects of education on changes in fertility over time. Drawing from the cross-sectional literature that has driven the education-TFR hypothesis, one is compelled to conclude that declines in fertility over time result from more women being educated. However, the emergence of fertility stalling post-2000 in some SSA countries raises questions against the assertion that education drives fertility decline. Therefore, while the question on the relationship between education and fertility has been addressed before, more research is still needed to sufficiently understand how education relates to fertility change over time. This study was thus designed to contribute to this need in existing literature thereby adding to the knowledge of fertility determinants in SSA. We focus on youth fertility because a reduction in the 15 to 24-year fertility level leads to reduction in future average parities of the 25 to 29-year age group which is usually the age group of peak fertility. Higher youth fertility populations have higher under-5 mortality (Trussell & Pebley, Citation1984; Kabir et al., Citation2001); many youths having births potentially perpetuates intergenerational poverty, thus slowing down the developing countries’ rate of development for demographic dividend (Bloom et al., Citation2003; Bongaarts & Casterline, Citation2013). Specifically, the study addresses the following questions;

Does the increase in educational attainment necessarily drive fertility decline?

Are the effects of education on changes in fertility of young people uniform across Ethiopia, Rwanda and Zimbabwe?

The rationale for focusing on Ethiopia, Rwanda and Zimbabwe is predicated by various reasons. In these three countries, data from DHS accessed through the STATcompiler (ICF, Citation2012) show that median ages at first birth barely changed since the year 2000. In Ethiopia, it has remained at 19 years between 2000 and 2020 while in Rwanda it barely increased from 22.0 to 22.7 years. In Zimbabwe, the median age at first birth increased from 19.5 in 2000 to 20.3 years in 2020. These small increases in the median age at first birth suggest that successive female birth cohorts have barely postponed the start of their childbearing careers compared to their older counterparts. The implication on fertility is that longer childbearing careers will negatively impact the rate of fertility decrease. An increase in the median age at first birth implies a reduction in the fertility rates of women aged 15–24 years which potentially reduces the TRFs of the countries.

Looking at Ethiopia separately, one of the highest population growths in SSA between 1970 and 2000 was recorded. In 1990, Ethiopia had 48 million people and this increased to 112 million by 2020 implying more than doubling in just 30 years (United Nations, Citation2019). This growth was driven by high fertility rates characterised by low median age at first birth and high mean age at childbearing ranging which only decreased from 30 to 29 years between 1980 and 2020.

The variation among these countries can be argued to mirror the diverse socioeconomic and political contexts of SSA countries thus provide a platform for an appraisal of the importance of education on fertility across the sub-region countries projected to account for most of the global population growth between 2019 and 2050 (United Nations, Citation2019).

With respect to Rwanda, the country’s unique extraordinarily rapid decline of TFRs, especially marital, never experienced anywhere else on the subcontinent makes it interesting case for the current study. It is worth noting that the sudden decline of fertility in Rwanda occurred within a decade after the end of the 1994 genocide which occurred amid a general decay of social infrastructures like education and health systems (Bundervoet, Citation2014). Given the socioeconomic recovery of Rwanda post-2000 and the attendant rapid decline of TFRs, it is interesting to understand the extent to which the fertility rates of young women were affected by changes in the levels of educational attainment. This is because over time, the effect of education on fertility is expected to be greater among the younger generations who would have had better access compared to their older counterparts (Bundervoet, Citation2014).

Zimbabwe was one of the leading countries from SSA to undergo fertility transition, but with a distinct characteristic of this being driven by older women as highlighted above (Udjo, Citation1996). Furthermore, Zimbabwe was one of the several countries from SSA to experience stalled fertility transition around the last and first decades of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries respectively (Garenne, Citation2008, Citation2011; Shapiro & Gebreselassie, Citation2009). An examination of the impact of primary and secondary education on the fertility of young women is therefore vital for the appreciation of the role of education in the fertility decline of Zimbabwe as well as understanding policy implications for the country’s total fertility goals in relation to its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)-related development plans.

2. Data and methods

The study analysed DHS data from Ethiopia, Rwanda and Zimbabwe collected between 1999 and 2011. The DHS uses retrospective survey design to collect data on various socioeconomic and demographic indicators including fertility histories of women aged between 15 and 49 years. For this study, data about number of births in the five years preceding a survey were used to estimate youth fertility and investigate its determinants with a focus on education. We used the Garenne (Citation2011) variant of the Own-Children Method (OCM) to calculate youth fertility rates. The Excel spreadsheet developed by Garenne & McCaa (Citation2017) was used to implement this method. A total sample of 31 202 females aged 15–24 years was analysed. For the period 2005/6 and 2010/11 the distribution of the sample for Ethiopia was 5869 and 6857, respectively and similarly 4951 and 5655 for Rwanda and 4075 and 3795 for Zimbabwe.

The analyses of data for this study involved two components; fixed effects multivariate regression analysis and application of simple direct decomposition technique. The multivariate regression analysis involved the cross-sectional application of fixed-effects logistic regression model, estimating odds of giving birth in the five years preceding a survey for two periods, 2005/2006 and 2010/2011 using country-level data. Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, Citation2015) was used to perform these analyses. The key determinant variable was education, divided into three categories namely none, primary, and secondary or higher. Control variables were age, age at sexual debut, modern contraceptive use, wealth status, place of residence, media exposure, ideal number of children, employment status and religion (). As a proxy indicator of fertility, we developed a binary variable based on whether a woman gave birth in the past five years which enabled the application of logistic regression model. The analysis of fertility using such an indicator has been adopted by other scholars in the past (Ezeh, Citation1997). It should be noted that this indicator of fertility over the five years preceding a survey has associated limitations. For instance, it does not fully capture the number of times a woman gave birth. The model is given as follows:where

is the proportion of young women aged 15–24 years who have given at least one birth in the past five years. The parameters

’s are regression coefficients related to

’s explanatory variables.

Table 1. Main explanatory variable and control factors used in fixed effects multivariate regression.

To understand the contributions of educational attainment to changes in youth fertility levels, the study employed direct decomposition technique to establish the roles of key categories of education status as sources of observed fertility trends. We follow the application of the technique by Yip et al. (Citation2015) who used the method to investigate changes in the fertility rates of Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Decomposition analysis was performed by splitting the twelve-year period from 1999 to 2011 into two periods that corresponded with the years when Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe collected DHS data. The first period [period 1] was the five years prior to the 2005/2006 DHS phases [1999/2000 to 2005/2006] and the second period [period 2] covered the five years preceding the 2010/2011 DHS phases [2005/2006 to 2010/2011]. We decomposed change in the level of youth fertility into two parts, one attributed to changes in age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) and the other explained by changes in the composition of each country’s youth population by education status. The method of decomposition allowed the study to separate and quantify the contributions, and nature of the contributions, of education to changes in youth fertility levels in the three countries.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

The median ages of the sample by country were 18.9, 19.3 and 19.4 years for Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe, respectively. The proportion of young women who had sexual debut before the age of 18 declined in Ethiopia and Rwanda but not in Zimbabwe where it remained relatively constant. Of the three countries, highest levels of childbearing for the five years preceding a survey were observed in Rwanda followed by Ethiopia ().

Table 2. Selected characteristics of females aged 15–24, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Zimbabwe, 2005/06, 2010/11 DHS.

The number of women who gave birth before age 18 were around 50%, 30% and 20% for Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, and Rwanda respectively. With respect to other characteristics, the distribution of young women was mostly rural-based, ranging from 58% in Zimbabwe 2005/6 to 84% in Rwanda 2010. Use of modern contraceptives among the young women ranged from 2% in Rwanda 2005 to 27% in Zimbabwe 2010. The percentage of young women who were never married ranged from 50% to 60% in Zimbabwe and Ethiopia to over 75% in Rwanda.

Large disparities were observed in the educational status of young women across the three countries. More than 70% of the respondents had secondary or higher education in Zimbabwe while only 17% had attained this level in Ethiopia. Meanwhile in Rwanda, attainment of higher education improved from 9% to 23% between 2005 and 2010. Illiteracy rates ranged from less than 1% in Zimbabwe to 6% in Rwanda and 26% in Ethiopia in the latest DHS. Illiteracy was reduced in Ethiopia from 49% to 26% between 2005/6 and 2010/11 ().

3.2. Trends in youth fertility

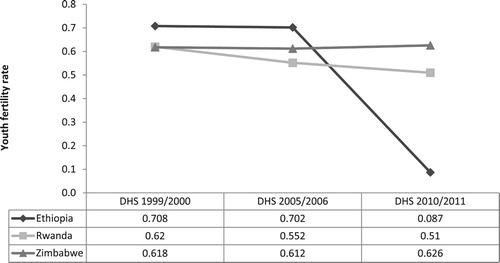

Univariate analysis of youth fertility showed that Ethiopia and Rwanda experienced declines over the two periods analysed with the former experiencing a sharp decline between 2000 and 2011 (). In Zimbabwe, youth fertility declined between 1999 and 2005 but a slight rebound reflective of stalled transition occurred between 2005 and 2010 ().

3.3. Unadjusted odds ratios of childbirth in the five years preceding a survey

shows the strong effect of selected determinants on the probability of giving birth for young women in the last five years preceding the survey. Delayed age (18 years and above) at sexual debut showed a negative and significant effect on the probability of giving birth except for Rwanda in the latest DHS surveys. Across the countries, modern contraceptive use, older age (20–24) and higher age (18years and older) at first birth have a positive and significant effect on youth childbearing. These results reflect that young women are exposed to their peak of childbearing or having births. Those who do not use modern contraceptives are partly not exposed to sexual intercourse or childbearing. Rural residence exposes young women to a higher risk of having a birth compared to living in urban areas across all the countries. This positive relationship between rural residence and youth fertility is significant except for the latest survey in Rwanda.

Table 3. Bivariate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logistic regression identifying association between youth childbearing and education as well as other selected variables.

Schooling has a strong negative effect on the probability of having birth across all the countries. Primary educational attainment has a significant decrease in the odds of giving birth except in Zimbabwe where the relationship is not significant. Having at least secondary education significantly reduced the odds of giving birth for all women from the three countries. The effect on fertility reduction of primary education was strongest in Ethiopia followed by Rwanda, being weakest in Zimbabwe. The change in the effect of primary education on odds of giving birth between 2005/6 and 2010/11 was greatest in Ethiopia followed by Rwanda and while very small in Zimbabwe. In Rwanda fertility control was stronger in the last survey for young women with secondary or higher education.

3.4. Multivariate youth fertility determinants

reports multivariate results estimating the net effect of education on youth fertility controlling for demographic and socioeconomic variables. Overall, net of other factors education has a negative effect on youth fertility in all countries. Effects of primary education were less consistent in the latest survey in Zimbabwe. The strong significant negative relationship between educational level and youth fertility was seen in Ethiopia and Rwanda. Young women with primary education were found to be over 50% less likely to have had a birth and those with secondary or higher education over 80% less likely to have a birth compared to those with no education. In Zimbabwe, the education-youth fertility relationship was not significant or was weakened with presence of other factors. Between the earlier and later survey the odds of having births increased for educated women.

Table 4. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals identifying effect of education on childbearing.

With respect to other factors, the association of youth fertility, and age and modern contraceptive use has remained the same showing a strong positive significant effect as in bivariate analyses. An inverse relationship between wealth status and fertility was observed in all countries except for the earlier surveys in Ethiopia and Rwanda portraying a different pattern. Effects of high fertility on rural residence were more consistent across the countries and significant in Ethiopia and Rwanda, except for the latest survey for Rwanda were urban fertility was higher than in rural. Overall, media exposure tends to decrease the chances of childbearing in all countries. The desire for a large number of children (3 or more) increases the odds of childbearing among young women in all the countries, except for Rwanda earlier survey. Being employed was found to decrease the odds of having birth in Zimbabwe, and much more significantly in Ethiopia. In Rwanda youth employment was found to increase the chances of childbearing among young women, but the association was not significant at the latest survey. Religion was also found to have an important role in determining fertility.

3.5. Decomposition: Effects of changes in ASFRs and fertility levels by education status

3.5.1. Period 1 [1999/2000 to 2005/06] effects

shows results from a decomposition of changes in youth fertility levels in the three countries over two periods examined in the study. In Ethiopia and Rwanda, the decline in youth fertility occurred in both age groups (15–19 and 20–24). The decline in the birth rates of the 20 to 24-year age group accounted for more than 60% (−0.002/−0.003 × 100) of the total decline in youth fertility in Ethiopia while in Rwanda it accounted for more than 50%. In Zimbabwe, a decline for ages 15–19 was observed for the first period with a rebound occurring in the second period. During the 1999–2005 period in Zimbabwe, the decline in youth fertility was due to a decrease of 0.007 in teenage fertility. The fertility of 20 to 24-year olds increased between 1999/2000 and 2005/06 in Zimbabwe by 0.004. This means that the decline in youth fertility observed for Zimbabwe in between 1999 and 2005, albeit slight, () was entirely due to the decline in teenage fertility.

Table 5. Decomposition of changes in youth fertility by age group and educational status.

A decomposition of the effects of education on youth fertility showed that Ethiopia experienced an increase in the birth rate of young women who reported no education while among those with primary and at least secondary education, birth rates declined between 2000 and 2005. This implies that primary education as well as secondary or higher had a depressing effect on overall youth fertility in Ethiopia during the five-year period between 2000 and 2005. The total effects of changes in education on youth fertility were negative in Rwanda and Zimbabwe. Rwanda experienced declines in youth fertility in all categories of education status while in Zimbabwe, a decline was observed among youths with no education while those with primary and secondary or higher had increased fertility.

3.5.2. Period 2 [2005/06 to 2010/11] effects

Ethiopia and Rwanda continued to experience declines in the fertility rates of both age groups 15–19 and 20–24. Consequently, the total effect of changes in the age-specific fertility rates was to depress youth fertility in the two countries (). In the contrary, Zimbabwe experienced decline in the fertility level of the 20–24 year age group while the fertility level of the 15–19 year age group increased. The decrease in the fertility level of the 20–24 year age group was smaller than the increase experienced in the 15–19 year age group. As a result, a rebound in youth fertility occurred in Zimbabwe during the five-year period between 2005/06 and 2010/11 due to an increase in teenage fertility.

Period 2 was characterised by increases in fertility levels of women with no education in all the three countries. However, while this was also the case among those with primary and secondary or higher education status in Zimbabwe, there were declines in the fertility levels of women with primary or higher education in Rwanda. In Ethiopia, fertility declined only among those with secondary or higher.

4. Discussion

This study found evidence to support the argument that a country with higher rates of secondary or higher educational attainment will realise limited benefits in the form of fertility reduction from increased access to primary education among young women. Our results confirm Gupta & Mahy’s (Citation2003) argument regarding the relationship between education and fertility in the context of high levels of access to primary education. When a country still has low levels of access to education, primary education becomes an important factor in reducing youth fertility. As argued in Caldwell (Citation1980) mass education in form of widespread access to primary schooling has a depressing effect on fertility, playing a significant role in the start of fertility transition. Caldwell’s (Citation1980) assertion is applicable to countries like Ethiopia and Rwanda that are still in the early stages of fertility transition. In such countries, the ideational change that is associated with the process of increasing breadth of education in a society is still important in reducing fertility (Meekers, Citation1994). This could also be explained in the context of low rates of educational attainment, the socioeconomic utility of primary education in terms of employment opportunities is relatively high compared to when a society has higher levels of secondary education attainment.

In the study by Lloyd et al. (Citation2000), primary education was observed to have a significant depressing effect on fertility in countries that include Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe during the 1980s and 1990s. As reported in Meekers (Citation1994), education enhances gender equality, allowing women to realise and exercise autonomy regarding use of contraception and postponing union formation thereby delaying onset of fertility. However, it can be argued that this cannot continue to be the case once a country has undergone considerable fertility transition and has reached higher levels of access to education both at primary and secondary level. This was proved in our analysis which showed that the significance of primary education on youth fertility was limited in Zimbabwe where access to education up to secondary level is high. Meanwhile, in Ethiopia and Rwanda where secondary educational attainment is still low, primary education showed significant importance in reducing youth fertility.

We used DHS data from Ethiopia, Rwanda and Zimbabwe collected between 1999 and 2011 to investigate the role of education on fertility among young women. Our focus was on examining the effect of primary education on levels and changes in youth fertility rates in the three countries. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios were estimated to measure the relationship between education and childbearing among young women. Direct decomposition analysis was explored to determine the contributions of educational attainment to changes in youth fertility. The outcome measure of recent fertility using occurrence of births over the five years preceding a survey has associated limitations. For instance, it does not fully capture any multiple births per woman that may occur. Though DHS surveys are cross-sectional making causal relationships difficult to determine in a given period, the understanding of young women’s fertility responses to education over time is enhanced by utilising the successive surveys conducted every five years. Thus an appraisal of education elasticities of fertility for this study was invoked. Consideration of utilising women’s community education, rather than at individual women’s level, on the subject matter might be of policy relevance for future research.

We found that at higher levels of secondary or higher educational attainment, the effect of primary education on the odds of giving birth is significantly reduced. This was the case with the unadjusted odds ratios of giving birth in Zimbabwe in the two periods analysed. In the context of low educational attainment at country level as was the case in Ethiopia and Rwanda, primary schooling significantly depressed the odds ratios of giving birth. Based on the results of this study, we conclude that primary education is still an important tool for fertility policy in countries like Ethiopia and Rwanda. However, there is urgent need to move beyond the focus on access to primary education to secondary and tertiary education in countries that have experienced universal access to primary education. As proved by results for Zimbabwe, the effect of primary education on the fertility of young women cannot continue to be significant indefinitely. This conclusion suggests that the levels of schooling of a population have a major influence on the levels and transition of fertility in any society. Hence, fertility levels among countries from SSA can be argued to respond to population-level educational attainment with varying elasticities depending on a country’s phase in fertility transition and/or level of economic development.

Ultimately, policies that promote an extended stay of girls in formal education, beyond secondary schooling which reduces their fertility markedly should be strengthened. Consequently, universal primary education may be an inadequate policy tool for reducing youth fertility. With supporting and implementing effective, inclusive and quality in-school and lifelong learning outcomes as envisioned by SGD number 4, there are reasonable further prospects for reducing youth fertility especially for disadvantaged girls in SSA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akin, MS, 2005. Education and fertility: A panel data analysis for Middle Eastern countries. Journal of Developing Areas 39(1), 55–69. https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jda/ Accessed 20 Sep 2019. doi: 10.1353/jda.2005.0030

- Behrman, J, 2015. Does schooling affect women’s desired fertility? Evidence from Malawi, Uganda, and Ethiopia. Demography 52(3), 787–809. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0392-3

- Bloom, DE, Canning, D & Sevilla, J, 2003. The demographic dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. Population Matters Monograph MR-1274, RAND, Santa Monica. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/2007/MR1274.pdf Accessed 21 Aug 2019.

- Bongaarts, J, 2003. Completing the fertility transition in the developing world: The role of educational differences and fertility in preferences. Population Studies 57(3), 321–36. doi: 10.1080/0032472032000137835

- Bongaarts, J, 2010. The causes of educational differences in fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 8, 31–50. doi: 10.1553/populationyearbook2010s31

- Bongaarts, J & Casterline, J, 2013. Fertility transition: Is sub-Saharan Africa different? Population and Development Review 38, 153–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00557.x

- Bundervoet, T, 2014. What explains Rwanda’s drop in fertility between 2005 and 2010? (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2376576). Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY.

- Caldwell, JC, 1980. Mass education as a determinant of the timing of fertility decline. Population and Development Review 6(2), 225–51. doi: 10.2307/1972729

- Channon, MD & Harper, S, 2019. Educational differentials in the realisation of fertility intentions: Is sub-Saharan Africa different? PLoS One 14(7), doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219736

- Chemhaka, GB & Odimegwu, CO, 2019. The proximate determinants of fertility in Eswatini. African Journal of Reproductive 23(2), 65–75. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i2.7

- Colleran, H & Snopkowski, K, 2018. Variation in wealth and educational drivers of fertility decline across 45 countries. Population Ecology 60, 155–69. doi: 10.1007/s10144-018-0626-5

- Edwards, S, 1996. Schooling’s fertility effect greatest in low-literacy, high-fertility societies. International Family Planning Perspectives 22(1), 43–4. doi: 10.2307/2950803

- Eloundou-Enyegue, PM & Giroux, SC, 2013. The role of fertility in achieving Africa’s schooling MDGs: Early evidence for sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Children and Poverty 19(1), 21–44. doi: 10.1080/10796126.2013.765836

- Ezeh, AC, 1997. Polygyny and reproductive behavior in sub-Saharan Africa: A contextual analysis. Demography 34(3), 355–68. doi: 10.2307/3038289

- Garenne, M, 2008. Situations of fertility stall in sub-Saharan Africa. African Population Studies 23(2), doi: 10.11564/23-2-319

- Garenne, ML, 2011. Testing for fertility stalls in demographic and health surveys. Population Health Metrics 9(59), doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-9-59

- Garenne, M & McCaa, R, 2017. 4-parameters own-children method: A spreadsheet for calculating fertility rates from census microdata: Application to selected African countries, in: Children, mothers and measuring fertility: New perspectives on the own child method. Presented at the Cambridge Meeting, 18–20 September, Cambridge, 1–38.

- Gupta, N & Mahy, M, 2003. Adolescent childbearing in sub-Saharan Africa: Can increased schooling alone raise ages at first birth? Demographic Research 8(4), 93–106. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2003.8.4

- Gyimah, SO, Takyi, B & Tenkorang, EY, 2008. Denominational affiliation and fertility behaviour in an african context: An examination of couple data from Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science 40(3), 445–58. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007002544

- ICF, 2012. The DHS Program STATcompiler. Funded by USAID. https://www.statcompiler.com Accessed 21 Jun 2019.

- International Labour Organisation, 2015. World employment and social outlook: Trends 2015. International Labour Office, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Kabir, A, Jahan, R, Islam, MS & Ali, R, 2001. The effect of child mortality on fertility. Journal of Medical Sciences 1(6), 377–80. doi: 10.3923/jms.2001.377.380

- Kravdal, Ø, 2012. Further evidence of community education effects on fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Demographic Research 27(22), 645–80. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.22

- Kravdal, Ø, 2002. Education and fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa: Individual and community effects. Demography 39(2), 233–50. doi: 10.2307/3088337

- Lloyd, CB & Blanc, AK, 1996. Children’s schooling in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of fathers, mothers, and others. Population and Development Review 22(2), 265–98. doi: 10.2307/2137435

- Lloyd, CB, Kaufman, CE & Hewett, P, 2000. The spread of primary schooling in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for fertility change. Population and Development Review 26(3), 483–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00483.x

- Meekers, D, 1994. Education and adolescent fertility in sub-saharan Arica. International Review of Modern Sociology 24(1), 1–43.

- Ndagurwa, P & Odimegwu, C, 2019. Decomposition of Zimbabwe’s stalled fertility change: A two-sex approach to estimating education and employment effects. Journal of Population Research 36(1), 35–63. doi: 10.1007/s12546-019-09219-8

- Population Reference Bureau, 2015a. 2015 world population data sheet. https://www.prb.org/wpds/2015/ Accessed 21 Sep 2019.

- Population Reference Bureau, 2015b. Total fertility rate, 1970 and 2014.

- Shapiro, D & Gebreselassie, T, 2009. Fertility transition in sub-Saharan Africa: Falling and stalling. African Population Studies 22(1), 1–23. doi: 10.11564/23-1-310

- StataCorp, 2015. Stata statistical software: Release 14. StataCorp LP, College Station, TX.

- Trussell, J & Pebley, AR, 1984. The potential impact of changes in fertility on infant, child and maternal mortality. Studies in Family Planning 15(6), 267–80. doi: 10.2307/1966071

- Uchudi, JM, 2001. Spouses’ socioeconomic characteristics and fertility differences in sub-Saharan Africa: Does spouse’s education matter? Journal of Biosocial Science 33(4), 481–502. doi: 10.1017/S0021932001004813

- Udjo, EO, 1996. Is fertility falling in Zimbabwe. Journal of Biosocial Science 28(1), 25–35. doi: 10.1017/S0021932000022069

- United Nations, 2019. World population prospects 2019: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/423). United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York.

- Yip, PSF, Chen, M & Chan, CH, 2015. A tale of two cities: A decomposition of recent fertility changes in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Asian Population Studies 11(3), 278–95. doi: 10.1080/17441730.2015.1093285