ABSTRACT

The periphery of the world economy is integrated into global production networks (GPNs) by ‘gateways’. These are intermediary places from where transnational corporations organise their business activities in close cooperation with corporate service providers. Gateways may also serve as logistics nodes as well as sites of industrial processing and knowledge generation. While some claim that gateways are engines of growth, others argue that they prosper at the expense of peripheral places. The article applies these thoughts to Mauritius, oil and gas GPNs, and the gateway's impact upon sub-Saharan Africa. The analysis indicates that Mauritius holds a certain potential for logistics and corporate control. The island serves as a hub of service provision already today. Only its status as a tax haven has a negative effect on resource peripheries. Against the backdrop of these findings, the authors discuss whether gateways should be seen as drivers or obstacles of peripheral development.

1. Introduction

The contemporary world economy is marked by geographical fragmentation of production. Since the mid-1990s, three approaches have been advanced to analyse this phenomenon. Standing in the tradition of world-systems analysis, research on global commodity chains aims at uncovering how lead firms from the core dominate their suppliers from the periphery (Gereffi & Korzeniewicz, Citation1994). Analyses of global value chains focus on inter-firm coordination and the prospects of development through ‘upgrading’ (Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2002; Gereffi et al., Citation2005). In publications on global production networks (GPNs), emphasis is put on the interplay of firms and regions (Coe et al., Citation2004; Coe & Yeung, Citation2015; Henderson et al., Citation2002). The three approaches pay rather little attention to intermediary places, meaning locations that connect others globally. Elsewhere, we (Citation2019) argue that the integration of the periphery into the world economy depends on ‘gateways’. Gateways integrate their respective hinterlands into GPNs, being logistics hubs, sites of industrial processing, locations of corporate headquarters and of firms that provide producer services, and/or places of knowledge generation.

We now apply the gateway concept to the island state of Mauritius, which – quite surprisingly – has assumed a considerable role in the oil and gas sector. We answer the question of how Mauritius interlinks sub-Saharan Africa globally. Hence, this article contributes to the gateway and GPN literatures by investigating an unexpected spatial intermediary. To avoid misunderstandings, we are not saying that Mauritius is the only gateway to sub-Saharan Africa – or the most important one. The firms that rely on Mauritius as an intermediary are important for the oil and gas sector, but they are not the sector's lead firms. We acknowledge that there are multiple gateways.Footnote1 Further to that, the article is not meant as a holistic study of Mauritius. It addresses a particular sector to better understand the role of Mauritius therein, which leads us to an expansion of the gateway concept – that is, to better recognise the relevance of gateways for financial offshoring.

In addition to the prospects of Mauritius as a gateway, we investigate its impact upon places that it interlinks globally. Mauritius's role as a financial hub – being part of the gateway dimension of service provision – has negative consequences for some hydrocarbon-rich countries because profits are reduced there through tax evasion or outright transferred to Mauritius, illustrating what Parnreiter (Citation2019) calls the ‘geographical transfer of value’. It therefore appears that a more critical perspective on gateways, which tend to be seen quite optimistically as enablers of mutually beneficial globalisation, is necessary. Building corresponding inroads and discussing the how gateways influence peripheral development is another contribution of the article to more general academic debates.

The article is structured as follows: first, we present the concept of gateways and show how it contributes to research on GPNs. We elaborate on negative effects that gateways may have on the periphery. Second, a summary of our case selection and methodology is provided. Third, we shed light on the role of Mauritius in oil and gas GPNs, revealing how the island state interlinks peripheral places worldwide. It does so especially through service provision and also holds a certain potential for logistics and corporate control. We critically assess its role as a tax haven.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Global production networks and gateways

Providing critical insights on regional development, GPN analysis uncovers how value is created, enhanced and captured in networks that link specific places or regions at the sub-national scale with extra-regional corporations. Much attention is paid to inter-firm organisation and the institutional context of such networks (Henderson et al., Citation2002; Coe & Yeung, Citation2015). The key idea is that regional development depends on how the region in consideration participates in GPNs – a process called ‘strategic coupling’. Most importantly, value must be captured locally so as to trigger further economic dynamics. As Coe & Yeung stress, foreign investment is not a sufficient condition for regional development, but ‘value must be retained within firms, or the parts of firms, based in the territory under question’ (Citation2015:172).

The local arrangements relating to the creation, enhancement and capture of value are seen as an outcome of the interplay of regional assets – which range from labour and resources to organisational forms such as clusters – with regional institutions and extra-regional corporations. In the ideal case, regional assets are moulded by regional institutions so that they meet the needs of extra-regional corporations, providing relevant economies of scale or scope (Coe et al., Citation2004). Localisation economies occur and GPNs are held down, unleashing the economic potential of the region in consideration. The role of regional institutions in this process goes beyond the transformation of regional assets. It also comprises bargaining with extra-regional corporations, for example on re-investing profits locally.

The GPN approach – and research on commodity and value chains alike – has paid little attention to places that interlink others. Yet, readers familiar with peripheral sites in the Global South will agree that there are connectors and hinges that allow for integrating such locations into the world economy – most demonstratively through transport infrastructure but also in terms of corporate control. There is some research on intermediary places in GPNs. Scholvin (Citation2017, Citation2019b) assesses the prospects of Cape Town, Durban and Johannesburg as hubs that interlink the oil and gas sector in sub-Saharan Africa globally. With regard to Singapore's role for this particular sector, Breul & Revilla Diez (Citation2017, Citation2018) demonstrate that the integration of peripheral places into GPNs is not direct. Instead, an ‘intermediate step’ is taken. Similar findings have been made on the electronics industry in Malaysia (Van Grunsven & Hutchinson, Citation2016) and offshore services in the Philippines (Kleibert, Citation2016), among other cases.

Further developing these inroads to better understand what Phelps (Citation2017) calls ‘interplaces’, we suggest conceptualising them as gateways. Research on gateways – or gateway cities – has become increasingly broad, covering maritime transport (Notteboom, Citation2007; Lee & Ducruet, Citation2009), international migration (Price & Benton-Short, Citation2008) as well as flows of foreign investment and trade (Grant Citation2008; Chubarov & Brooker, Citation2013). Various scales have been addressed in the gateway literature. For example, Cohen (Citation1990, Citation1991) considers quasi states being gateways. Grant and Oteng-Ababio (Citation2016) call sites of e-waste recycling ‘urban gateways’ in global networks. Regardless of their territorial extension, we follow Burghardt in defining gateways as ‘an entrance into (and necessarily an exit out of) some area’ (Citation1971:269). Mainstream research on gateways relates to the world city literature (Friedmann Citation1986; Sassen Citation2001; Taylor et al., Citation2002; Derudder & Taylor, Citation2016). Yet while the world city literature is largely concerned with city–city interaction, research on gateways deals with city–hinterland ties. Rather than being a different real-world phenomenon, gateways hence constitute a distinct analytical perspective.

Being particularly close to the world city literature, Meyer et al. (Citation2009), Parnreiter (Citation2010), Parnreiter et al. (Citation2013) as well as Rossi et al. (Citation2007) analyse cities in the Global South as gateways with a focus on corporate service providers and, to a lesser extent, corporate headquarters. Other scholars suggest that the functions fulfilled by gateways go beyond corporate control and corporate services (Short et al., Citation2000; Sigler, Citation2013). As noted, we (Citation2019) propose an understanding of gateways based on five dimensions. They result from a survey of the literature on GPNs and world cities, and cover everything that is necessary for integrating peripheral places into the world economy. The dimensions are not necessarily additive, meaning that a particular gateway can be marked by any combination of them. Gateways are logistics hubs. In the Global South, they are also home to large-scale industries that are linked across national borders. Further to that, corporate control and various corporate services mark gateways. They generate knowledge – in the sense that global knowledge is adapted to local specificities there. Alternatively, gateways may be stepping stones for innovative local firms seeking to internationalise their business dealings.

2.2. The developmental impact of gateways

With a few exceptions, the aforementioned publications say little about the impact of gateways upon the development of the places they interlink globally. Some are marked by a certain optimistic notion in this regard. Organisations such as the World Bank argue that the integration into the world economy leads to positive outcomes for the periphery. Most prominently, the World Development Report from 2009 suggests that developing countries bind themselves to nearby ‘leading areas’, allowing for the free flow of capital, goods and people so as to benefit from impulses that leading areas supposedly generate (World Bank, Citation2009). In academia, this optimism is best exemplified by Morris et al.’s (Citation2012) seminal publication on the commodities sector. They argue that developing countries will benefit from integration into GPNs if the right policies are in place (see also: Kaplinsky et al., Citation2011).

We take a more sceptical perspective, but we are not the first to do so. Parnreiter (Citation2019) suggests that providers of corporate services, which are based in world cities that serve as gateways, organise the geographical transfer of value from the periphery to the core. Corporate service providers enforce property rights and grant access to finance. Labour relations are another means through which these firms increase the profits of their clients. Understood this way, the geographical transfer of value is about altering value capture in GPNs, rather than an actual transfer of money from one place to another. What we find particularly striking in this regard is that research on gateways has paid no attention to the downsides of financial offshoring. Of course, financial offshore as a general phenomenon has been studied intensively. Important contributions on the GPNs of finance and the role of cities in these networks have been made by Dörry (Citation2014, Citation2015) and Van Meeteren & Bassens (Citation2016), among others. Yet, research on gateways and financial flows – for example by Bassens et al. (Citation2010), Cobbett (Citation2014) and Warf & Vincent (Citation2003) – appears to merely confirm the existence and relevance of this form of interlinking, but it does not analyse the relating effects on other places.

Besides the need to shed light on financial offshoring, we concur with criticism of world city research by post-colonial scholars and adherents of the GPN approach (Robinson, Citation2002; Coe et al., Citation2010) insofar as we contend that analysing only corporate service provision provides an incomplete and potentially misleading picture of intermediaries in GPNs. Assessing interlinking through gateways from a broader perspective, Breul et al. (Citation2019) reason that Singapore limits the potential of strategic coupling in Indonesia and Vietnam because of different filtering mechanisms. As noted, regional institutions bargain with extra-regional corporations – and this applies to peripheral locations and gateways. Both seek to tie down GPNs. With regard to sophisticated, high value-adding tasks, gateways outcompete peripheral locations. The existence of a gateway decreases the need to carry out certain activities in the periphery. Gateways also benefit from path dependencies, once a lead firm has invested in industrial processing or located corporate control there. The scepticism on gateways as engines of growth is boosted by the generally poor performance of peripheral locations that participate intensively in GPNs. Studies on commodity source regions such as the north of Chile and Pilbara in Western Australia, for instance, reveal that their coupling with extractive GPNs brings about few positive local outcomes, mostly in terms of generic services (MacKinnon, Citation2013; Arias et al., Citation2014).

In sum, the role of gateways in GPNs is highly contested and we seek to make a contribution to better understanding whether they are growth engines that work to the benefit of the places they interlink globally or, alternatively, filter gains and/or allow for the geographical transfer of value. We do so within the limits of an analysis focussed on the gateway itself and, as noted, a sector that is not, probably, representative of global and regional networks. While we are able to discuss what Mauritius's role means for some peripheral locations that have plugged into oil and gas GPNs, we cannot say how these sites are affected by investment that is not channelled through Mauritius. Nor do we claim that our analysis necessarily provides a general picture of Mauritius's relationship with sub-Saharan Africa.

3. Case selection and methodology

Mauritius is not the first place that comes to mind when one thinks about oil and gas. The island has no proven hydrocarbon reserves. All oil products are imported from India. Still, we did not accidently decide to study Mauritius's role in oil and gas GPNs. Our initial interest resulted from desk studies on foreign investment in the oil and gas sector across sub-Saharan Africa, which revealed that Mauritius had hitherto been involved in some corresponding projects. For example, the Indian firm Mangalore Refinery and Petrochemicals signed a memorandum of understanding with Mauritius's State Trading Corporation (STC) in 2014 on a yet-to-be-built petroleum terminal that will serve for re-exports to sub-Saharan Africa and islands in the Indian Ocean (World Maritime News, Citation2014). Desk studies of policy documents – the second step that we took – then showed that the oil and gas sector is part of Mauritius's strategic economic planning, which includes, as one pillar, the ‘ocean economy’ (Board of Investment, Citation2015; Government Information Service, Citation2016). With regard to a role as a hinge between the core and the periphery of the world economy, the Three-Year Strategic Plan points out that Mauritius aims to ‘position itself as the gateway to Africa for Asian, European and Middle Eastern businesses’ (Republic of Mauritius, Citation2016:15).

This preliminary research was published as a book chapter that provides an overview of the different ways in which Mauritius serves as a gateway, neglecting the question of how the island state influences development of places that it interlinks globally (Scholvin, Citation2019a). The empirical analysis further below is based on information obtained from policy papers, indexes that describe the business environment of Mauritius as well as publically available documents on two Mauritius-based holding structures involved in the oil and gas sector. The latter source of information closes the gap left by the just mentioned book chapter. Capturing the transfer of value across corporate networks is challenging due to a lack of data. We found the Offshore Leaks database helpful to grasp the practices of corporations that shift value from other jurisdictions to Mauritius. However, this database only contains three entries related to Mauritius and the oil and gas sector, unfortunately without details on financial flows (International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Citation2019).

Further to that, we conducted 16 narrative interviews in September 2017, which were also by Scholvin (Citation2019a). The interviewees were identified via LinkedIn. Snowballing was applied subsequently. All interviewees spoke as individuals, not as representatives of a particular firm or public authority, although their corresponding affiliations are indicated here. The interviews were based on a guideline of 12 questions (on inter-firm organisation, relationships with other companies, location advantages and regional integration). We recorded the interviews, with four exceptions (notes were taken instead), and analysed them by structuring the information with the help of categories defined prior to the actual research trip itself.

4. Empirical analysis

4.1. Bunkering, logistics and engineering services

The first advantage that Mauritius offers as a gateway is a population fluent in both English and French – languages that are obviously essential for doing business in sub-Saharan Africa. This location advantage was mentioned in several of our meetings. An interviewee said that ‘we speak three or four languages; most of us: English, French and, some of us, Hindi’.Footnote2 This is critical for the interviewee's company because it heavily relies on labour from India (more on this later).

The aforementioned Three-Year Strategic Plan states that the government will seek ‘to expand the economic space for Mauritian firms through enhanced economic integration and cooperation [in sub-Saharan Africa]’ (Republic of Mauritius, Citation2016:2). Mauritius is a member of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). In 2000, COMESA's free trade area was formed. IORA is not a free trade area, but its member states have made a commitment to facilitate greater intra-community investment and trade. SADC established a free trade area in 2008. On a bilateral level, Mauritius has signed double-taxation-avoidance agreements with 14 sub-Saharan African countries and investment protection and promotion ones with 8 countries from that subcontinent too.Footnote3

Mauritius moreover offers a business environment that is unique in sub-Saharan Africa. It is the best performer from the subcontinent in the Ease of Doing Business rankings, slightly ahead of Rwanda and clearly so of Kenya and South Africa (World Bank, Citation2017). The Global Competitiveness Report and the Index of Economic Freedom both confirm that Mauritius is a liberalised market economy with efficient and reliable institutions (Heritage Foundation, Citation2017; World Economic Forum, Citation2017). The hydrocarbon-rich countries of sub-Saharan Africa – countries such as Angola, Chad, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon – are among the worst performers worldwide in all of these ranking. In other words, the business environment, regional economic integration and multiple languages turn Mauritius into an advantageous location for overseas companies that do business in sub-Saharan Africa.

The island also possesses good infrastructure dedicated to oil and gas, which implies that there are certain prospects for serving as a logistics hub. In 2008, an oil jetty was inaugurated in Port Louis. It reaches a throughput capacity of about 4 million tonnes a year. Storage facilities for 15,000 tonnes of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) were opened near the jetty in 2014. This LPG infrastructure is the largest in sub-Saharan Africa. Its owner, Petredec, along with the Mauritius Ports Authority (MPA, Citation2011) expect it to turn the country into an LPG hub in the Indian Ocean and for the east coast of Africa too. In order to bunker fuel oil, the Mer Rouge Oil Storage Terminal was completed in 2017. It reaches a capacity of 25,000 tonnes. The project derives from a joint venture between the STC and four international oil companies, namely Engen, Indian Oil, Total and Vivo Energy. An interviewee from the MPA pointed out that the rationale behind promoting Mauritius as a bunkering hub is that 30,000–35,000 ships travel from Asia around the Cape of Good Hope to Europe and the Americas each year. Mauritius is located close to this major sea route. It will attract a considerable number of vessels if it offers fuel at a competitive price and guarantees short waiting times.Footnote4

With regard to challenges, the interviewee from the MPA pointed out that Mauritius does not, currently, have a refinery. All petroleum products are imported from India, which makes them rather expensive. An interviewee from a major downstream firm explained that Singapore and the South African ports of Durban and Port Elizabeth – all three located on the aforementioned sea lane – are more competitive regarding pricing. Mauritius is able to compete with South African harbours because of advantages in terms of punctuality. Compared to Singapore, however, ‘we are out’ remarked this interviewee.Footnote5 The small domestic market also constitutes a problem for maritime services and ship repairs. Presently, there is only one company in Mauritius that can handle waste material from larger ships. The two dry-docking shipyards in Port Louis – Chantier Naval de l’Océan Indien and Taylor Smith & Co – repair ships for the fishing industry. They would have to upgrade their capacities to be able to service the oil and gas sector.

Against this backdrop, logistics appears to offer uncertain prospects for Mauritius as a gateway. Providing services to sub-Saharan Africa is more promising. An interviewee from an engineering firm referred to cheap labour (regarding engineers, and in comparison to Europe), experience in oil and gas, and innovative technologies in order to explain the competitive advantages of his company. With regard to a gateway role, it is interesting that this interviewee stressed that a French enterprise recently bought his company to gain better access to the markets of the subcontinent. What his company provides is expertise in doing business in sub-Saharan Africa. He also suggested that his employees are better prepared to work there: ‘Europeans are out of their comfort zone [in sub-Saharan Africa]. That is not a problem for Mauritians’.Footnote6 The interviewee added that Mauritians face fewer problems with work visas due to regional integration. Hence, regional connectivity – in terms of professional networks and the ability/willingness to travel across sub-Saharan Africa – is vital to Mauritius's gateway role.

Others explained that the design for engineering projects abroad is carried out in their company's facilities in Port Louis; so is pre-fabrication too. The materials for this are sourced globally. Mauritius's strength lies in being home to skilled engineers. While the project management team is, hence, always Mauritian, the company seeks to hire manual labour locally – for example in Tanzania – but often struggles to find sufficiently skilled people. The corresponding gaps are closed by labour brought in from India, proving the intermediary role of Mauritius in GPNs, as the interviewees themselves emphasised.Footnote7 Mauritius's global connectivity thus reinforces its suitability as a spatial intermediary.

As the previous paragraphs indicate, Mauritius has undertaken considerable efforts to position itself as a hub in the oil and gas sector. It partly serves as a gateway already today. So far, our analysis does not lead to a clear picture with regard to effects on the periphery. The bunkering strategy, including related services, means competition for Singapore and South African ports. If successful, this strategy will allow Mauritius to benefit from economic dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. The island state does not boost peripheral development by serving as a bunkering hub, however. If Mauritius built an oil refinery, changing trade patterns would be at the expense of India, although one may argue that industrial processing in Mauritius and ensuing exports to sub-Saharan Africa would limit the prospects of such development in countries like Kenya or Mozambique, reducing dynamics there to lower-value activities.

With regard to engineering services, Mauritius does not filter the gains from participation in GPNs or enable the geographical transfer of value. If there were no Mauritian engineering firms, transnational clients would probably hire companies from overseas or South Africa because of the lack of corresponding expertise in many sub-Saharan African countries. As a side note, this also explains Cape Town's present gateway role (Scholvin, Citation2017, Citation2019b). Mauritius does not compete with peripheral locations over GPN segments. The island state appears to specialise in sophisticated services, whereas some parts of the sub-Saharan African periphery do not possess sufficient regional assets to localise even basic oil and gas-related activities, as the example of Indian labour employed by a Mauritian firm for a project in Tanzania implies. Without further developing their own assets, these locations will remain unsuitable for strategic coupling, with the exception of mere resource provision.

4.2. Mauritius as a financial hub

The most interesting gateway function fulfilled by Mauritius is its role as a financial hub. More than three quarters of Mauritius's outward foreign direct investment goes to developing countries. Apparently, most of this money is previously transferred to Mauritius from the Global North. A recent study commissioned by the Investment Facilitation Forum finds that Mauritius is the main source of foreign direct investment for a number of countries in the Indian Ocean and sub-Saharan Africa. The corresponding share for Rwanda reaches an impressive 90 per cent. For South Sudan and Uganda, it stands at 69 and 42 per cent respectively (Hers et al., Citation2018).

In addition to the aforementioned highly favourable business environment, Mauritius is attractive as a financial hub because of several regulatory advantages. It has no foreign exchange controls and overseas companies enjoy the free repatriation of profits. The effective corporate tax rate is 3 per cent and, as noted, there are double-taxation-avoidance agreements in place with various countries. As an interviewee from a holding company pointed out, even in cases where there is no such treaty, Mauritian entities can still reclaim withholding taxes paid abroad.Footnote8 Double-taxation-avoidance agreements are intended to ease investment and trade by avoiding that the same activity is taxed twice. Still, they also enable transnational companies to restructure their operations for the sole purpose of decreasing tax obligations. Transnational companies can establish an intermediary unit in a country such as Mauritius in order to invest elsewhere, thereby exploiting the advantages of double-taxation-avoidance agreements.

Companies from various sectors, including oil and gas, are attracted by Mauritius's tax treaty network. Their relocation to the island is eased by numerous consultancies such as EY and KPMG, but it appears to us these consultancies follow their clients’ demand. The consultancies do not make other businesses relocate to Mauritius. Tax treaties do. The interviewee from the just-mentioned holding company explained that the group she works for presently has subsidiaries in Angola, Ghana and Mozambique. When the holding structure was set up in 2007, it did not have any employees. Today, it employs the interviewee and a secretary. Their duty is to transfer profits from the subsidiaries to Mauritius so that it is freely available to the owners of the group and can be held in a stable currency, as Mauritius allows firms to have bank accounts in United States dollars. In other words, capital is sucked out of the periphery. The profits made in resource peripheries do not stay there, making it very unlikely that participation in corresponding GPNs will trigger economic dynamics beyond initial investments in material assets and, in some cases, the employment of local labour.

In addition to these activities, the interviewee said that her company was thinking about hiring a marketing executive for the office in Mauritius. A representative of an international consultancy explained that such an expansion of activities is a common next step for firms that have their holding structure in Mauritius. These firms start, at a certain point, to concentrate their contract management and procurement on the island, centralising these activities for all countries where they operate. Doing so enables the respective firms to benefit from the financial advantages of Mauritius and to avoid the risks associated with running a business in a number of unstable currencies.Footnote9 Another interviewee from a different consultancy agreed, saying that many companies start with mere holding structures in Mauritius and eventually relocate more and more control functions to the island, especially board meetings.Footnote10

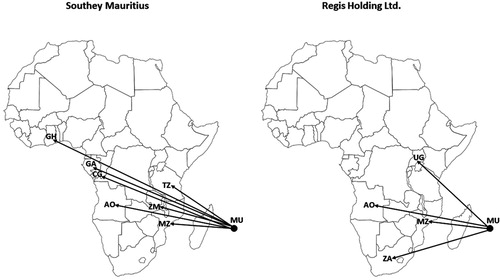

We have reconstructed the spatio-organisational patterns of two companies that use Mauritius as a financial hub (). These cases are not representative of the oil and gas sector as a whole, but they exemplify this critical role of Mauritius in GPNs. A firm called Southey provides technical services to the upstream sector that range from engineering and maintenance to offshore crew assignments and inspections. Originally a South African entity, Southey became part of a holding structure registered in Mauritius more than ten years ago. The holding bundles operations in Angola, Gabon, Ghana, Mozambique, the Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Zambia. It also has investments in Oman (Southey Mauritius, Citation2019), although it appears that Southey does not have on-going activities in all of these countries, presumably as a result of the decline of the oil price.

Figure 1. Sub-Saharan African ties of Regis Holdings and Southey.

Note: AO = Angola, CG = Congo, Rep., GA = Gabon, GH = Ghana, MU = Mauritius, MZ = Mozambique, TZ = Tanzania, UG = Uganda, ZA = South Africa, ZM = Zambia. Source: Authors’ own compilation.

Having a holding structure in Mauritius enables Southey to reduce its tax obligations in the countries where it provides its services. To give an example, the subsidiary in the Republic of the Congo can reduce taxes on dividends from 15 to 5 per cent. Royalties and taxes on interests as well as the management fee drop from 20 to 0 per cent (International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Citation2017). Hence, the creation of value physically occurs in resource peripheries, but the related tax obligations are reduced because of Mauritius serving as a gateway. In a study on 41 African countries, Beer and Loeprick (Citation2018) find revenue losses of 15–25 per cent of corporate income tax for countries that have implemented double-taxation-avoidance agreements with Mauritius and other financial hubs.

Adding another example, Regis Holdings offers services that relate to equipment, logistics, procurement and recruitment to companies that explore and extract hydrocarbons. The head office of Regis is registered in Mauritius. It owns subsidiaries in Angola, Mozambique, South Africa and Uganda. For instance, Regis Uganda has been contracted by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation and Total for exploration in Lake Victoria. It is also involved in the construction of a pipeline from there to the coast of the Indian Ocean in neighbouring Tanzania (Regis Holdings, Citation2019). Due to ownership in Mauritius, the management fee, royalties as well as tax obligations for dividends and interests of Regis Uganda are reduced from 15 to 10 per cent (International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Citation2017).

5. Conclusion

This article explained how Mauritius contributes to interlinking sub-Saharan Africa globally and also discussed its impact upon those places that it integrates into oil and gas GPNs. Mauritius's bunkering strategy demonstrates that the island state has undertaken efforts to position itself as a logistics gateway. Industrial processing is a related option. Yet, our research suggests that Mauritius's role as a gateway may rather be best based on flows of information. They comprise engineering expertise and benefit from the ease and experience of local firms in doing business in sub-Saharan Africa. The island is also attractive for holding structures. Having a holding company in Mauritius appears to be the first step towards relocating business services and some headquarter functions to the gateway. We did not elaborate on knowledge generation, which plays a negligible role for Mauritius and the oil and gas sector, as shown elsewhere (Scholvin, Citation2019a).

Mauritius's role in logistics and engineering services cannot be related to the aforementioned negative effects of gateways, but these activities do not appear to trigger peripheral dynamics either. With regard to financial flows, the negative impact is clear: the gateway allows some companies to withdraw profits from places of resource extraction. Double-taxation-avoidance agreements significantly reduce the tax income in resource peripheries. Firms that have their holding structure in Mauritius obviously invest in material assets located in resource peripheries and sometimes also contract local labour. Morris et al. (Citation2012) rightly point out that there are opportunities for developing countries to generate linkages from such investment. Yet following Coe & Yeung (Citation2015), realising these opportunities depends on value being re-invested locally and Mauritius – as a financial gateway – works against these dynamics.

We deem it best to add that any argument on filtering mechanisms and the geographical transfer of value avoids the question of whether and how the periphery would integrate into the world economy if there were no gateways. Is it realistic to expect sophisticated corporate services to be carried out in Chad or Equatorial Guinea? Would complex engineering be done by firms from parts of sub-Saharan Africa where it is, at present, impossible to find welders sufficiently qualified for the oil and gas sector? Our analysis suggests that gateways do not necessarily compete with peripheral locations over GPN segments. Mauritius concentrates on activities that are too sophisticated for the places of oil and gas extraction in sub-Saharan Africa.

Further to that, the rise of Mauritius as a gateway results at least partly from the unattractiveness of investing in the hydrocarbon-rich countries of sub-Saharan Africa. GPN analysis emphasises that regional development depends on how regional institutions mould regional assets so that they meet the needs of extra-regional corporations. Mauritius has been quite effective in this regard. If countries such as Angola and Gabon performed better, they would benefit from their resource endowment (and Mauritius's importance as a gateway would decline).

Acknowledgments

A first draft of this article was presented at a conference held in Stellenbosch, South Africa, in October 2017. The authors are grateful for the financial support that the Volkswagen Foundation provided to make this event possible. Comments by Anthony Black, Javier Diez and Ivan Turok were helpful to further develop the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 This reflects a key conviction from GPN analysis: production networks are firm-specific, meaning that each firm has a network of its own whose particularities result from firm-specific strategies to improve the cost–capability ratio (Coe & Yeung, Citation2015). If networks are different from one firm to another, they are even more different from one sector to another. Our analysis of the oil and gas sector is potentially as insightful as a study of, for example, Mauritius's role in information and technology networks. The fact that we have chosen this particular sector merely results from our previous experience with oil and gas GPNs.

2 Interview with an engineering and construction company, Port Louis, 21 September 2017.

3 A full list, including detailed information on these double-taxation-avoidance agreements, is available online at: www.mra.mu/index.php/taxes-duties/double-taxation-agreements. For a complete list of the investment protection and promotion agreements, see: www.investmauritius.com/downloads/ippa.aspx.

4 Interview with the MPA, Port Louis, 11 September 2017.

5 Interview with a major downstream company, Port Louis, 28 September 2017. The oil and gas industry is usually divided into three sectors: down-, mid- and upstream. The upstream sector includes searching for oil and gas fields, drilling wells and also operating these wells. The midstream sector involves the transport, storage and wholesale marketing of crude and purified/refined products. The downstream sector comprises refining crude oil and purifying raw natural gas, as well as the marketing and distribution of consumer products.

6 Interview with an engineering company, Vacoas-Phoenix, 26 September 2017.

7 Interviews with an engineering and construction company, Moka and Port Louis, 14 and 21 September 2017.

8 Interview with an upstream service provider, Grand Baie, 18 September 2017.

9 Interview with an international consultancy, Ebène, 19 September 2017.

10 Interview with an international consultancy, Ebène, 12 September 2017.

References

- Arias, M, Atienza, M & Cademartori, J, 2014. Large mining enterprises and regional development in Chile: Between the enclave and cluster. Journal of Economic Geography 14(1), 73–95. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbt007

- Bassens, D, Derudder, B & Witlox, F, 2010. Searching for the Mecca of finance: Islamic financial services and the world city network. Area 42(1), 35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00894.x

- Beer, S & Loeprick, J, 2018. The cost and benefits of tax treaties with investment hubs: Findings from sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank, Washington. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/325021540479671671/pdf/WPS8623.pdf Accessed 8 May 2019.

- Board of Investment, 2015. The 2015–2019 government programme. Board of Investment, Ebène. http://www.investmauritius.com/newsletter/2015/January/article1.html Accessed 13 April 2017.

- Breul, M & Revilla Diez, J, 2017. Städte als regionale Knoten in globalen Wertschöpfungsketten: Räumlich-funktionale Spezialisierungsmuster am Beispiel der Erdöl- und Erdgasindustrie in Südostasien. ZeitschriftfürWirtschaftsgeographie 61(3–4), 156–73.

- Breul, M & Revilla Diez, J, 2018. An intermediate step to resource peripheries: The strategic coupling of gateway cities in the upstream oil and gas GPN. Geoforum 92, 9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.03.022

- Breul, M, Revilla Diez, J & Sambodo, MT, 2019. Filtering strategic coupling: Territorial intermediaries in oil and gas global production networks in Southeast Asia. Journal of Economic Geography 19(4), 829–51. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lby063

- Burghardt, AF, 1971. A hypothesis about gateway cities. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 61(2), 269–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1971.tb00782.x

- Chubarov, I & Brooker, D, 2013. Multiple pathways to global city formation: A functional approach and review of recent evidence in China. Cities 35, 181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2013.05.008

- Cobbett, E, 2014. Johannesburg: Financial ‘gateway’ to Africa. In S Curtis (Ed.), The power of cities in international relations. Routledge, London.

- Coe, NM, Hess, M, Yeung, HW, Dicken, P & Henderson, J, 2004. ‘Globalizing’ regional development: A global production networks perspective. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 29(4), 468–84. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00142.x

- Coe, NM, Dicken, P, Hess, M & Yeung, HW, 2010. Making connections: Global production networks and world city networks. In B Derudder & F Witlox (Eds.), Commodity chains and world cities. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

- Coe, NM & Yeung, HW, 2015. Global production networks: Theorizing economic development in an interconnected world. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Cohen, SB, 1990. The world geopolitical system in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Geography 89(1), 2–12. doi: 10.1080/00221349008979817

- Cohen, SB, 1991. Global geopolitical change in the post-Cold War era. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 81(4), 551–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01709.x

- Derudder, B & Taylor, PJ, 2016. Change in the world city network, 2000–2012. Professional Geographer 68(4), 624–37. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2016.1157500

- Dörry, S, 2014. Global production networks in finance: The example of Luxembourg’s investment fund industry. L’Espace Géographique 43(3), 227–39. doi: 10.3917/eg.433.0227

- Dörry, S, 2015. Strategic nodes in investment fund global production networks: The example of the financial centre Luxembourg. Journal of Economic Geography 15(4), 797–814. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu031

- Friedmann, J, 1986. The world city hypothesis. Development and Change 17(1), 69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.1986.tb00231.x

- Gereffi, G & Korzeniewicz, M (Eds.), 1994. In Commodity chains and global capitalism. Praeger, Westport.

- Gereffi, G, Humphrey, J & Sturgeon, T, 2005. The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy 12(1), 78–104. doi: 10.1080/09692290500049805

- Government Information Service, 2016. Oil storage terminal project will propel Mauritius into next phase of development, says PM. Government Information Service, Port Louis. http://www.govmu.org/English/News/Pages/Oil-Storage-Terminal-project-will-propel-Mauritius-into-next-phase-of-development,-says-PM.aspx Accessed 14 April 2017.

- Grant, R, 2008. Globalizing city: The urban and economic transformation of Accra, Ghana. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse.

- Grant, R & Oteng-Ababio, M, 2016. The global transformation of materials and the emergence of informal urban mining in Accra, Ghana. Africa Today 62(4), 3–20. doi: 10.2979/africatoday.62.4.01

- Heritage Foundation, 2017. 2017 index of economic freedom. Heritage Foundation, Washington. http://www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2017/book/index_2017.pdf Accessed 6 October 2017.

- Hers, J, Witteman, J, Rougoor, W & Van Buiren, K, 2018. The role of investment hubs in FDI, economic development and trade: Ireland, Luxembourg, Mauritius, the Netherlands, and Singapore. Seoamsterdam economics, Amsterdam. http://www.seo.nl/uploads/media/2018-40_The_Role_of_Investment_Hubs_in_FDI__Economic_Development_and_Trade_01.pdf Accessed 8 May 2019.

- Henderson, J, Dicken, P, Hess, M, Coe, NM & Yeung, HW, 2002. Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Review of International Political Economy 9(3), 436–64. doi: 10.1080/09692290210150842

- Humphrey, J & Schmitz, H, 2002. How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies 36(9), 1017–27. doi: 10.1080/0034340022000022198

- International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, 2017. Tax haven Mauritius’ rise comes at the rest of Africa’s expense: Companies are rushing to the island nation to benefit from secrecy and tax benefits. International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Washington. https://www.icij.org/investigations/paradise-papers/tax-haven-mauritius-africa Accessed 18 February 2019

- International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, 2019. Offshore leaks database. International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Washington. https://offshoreleaks.icij.org Accessed 30 April 2019

- Kaplinsky, R, Morris, M & Kaplan, D, 2011. Commodities and Linkages: Meeting the Policy Challenge. MMCP Discussion Paper 14, Open University, Milton Keynes. http://oro.open.ac.uk/30049 Accessed 13 January 2020.

- Kleibert, JM, 2016. Global production networks, offshore services and the branch-plant syndrome. Regional Studies 50(12), 1995–2009. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1034671

- Lee, SW & Ducruet, C, 2009. Spatial glocalization in Asia-Pacific hub port cities: A comparison of Hong Kong and Singapore. Urban Geography 30(2), 162–84. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.30.2.162

- MacKinnon, D, 2013. Strategic coupling and regional development in resource economies: The case of the Pilbara. Australian Geographer 44(3), 305–21. doi: 10.1080/00049182.2013.817039

- Meyer, S, Schiller, D & Revilla Diez, J, 2009. The Janus-faced economy: Hong Kong firms as intermediaries between global customers and local producers in the electronics industry. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 100(2), 224–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2009.00531.x

- Morris, M, Kaplinsky, R & Kaplan, D, 2012. One thing leads to another: Promoting industrialisation by making the most of the commodity boom in sub-Saharan Africa. Lulu, Raleigh.

- MPA, 2011. Corporate plan 2012–2014. MPA, Port Louis. http://www.mauport.com/sites/default/files/public/corporate_plan_2012.pdf Accessed 5 October 2017

- Notteboom, T, 2007. Container river services and gateway ports: Similarities between the Yangtze River and the Rhine River. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 48(3), 330–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8373.2007.00351.x

- Parnreiter, C, 2010. Global cities in global commodity chains: Exploring the role of Mexico City in the geography of global economic governance. In B Derudder & F Witlox (Eds.), Commodity chains and world cities. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

- Parnreiter, C, 2019. Global cities and the geographical transfer of value. Urban Studies 56(1), 81–96. doi: 10.1177/0042098017722739

- Parnreiter, C, Haferburg, C & Oßenbrügge, J, 2013. Shifting corporate geographies in global cities of the south: Mexico City and Johannesburg as case studies. Die Erde 144(1), 1–16.

- Phelps, NA, 2017. Interplaces: An economic geography of the inter-urban and international economies. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Price, M & Benton-Short, L (Eds.), 2008. In Migrants to the metropolis: The rise of immigrant gateway cities. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse.

- Regis Holdings, 2019. Our current areas of operations. Regis Holdings, Black River. http://www.regis.co.za/operations.html Accessed 20 February 2019.

- Republic of Mauritius. 2016. Three year strategic plan: 2017/18 to 2019/2020. Republic of Mauritius, Port Louis. http://budget.mof.govmu.org/budget2017-18/2017_183-YearPlan.pdf Accessed 14 April 2017.

- Robinson, J, 2002. Global and world cities: A view from off the map. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26(3), 531–54. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00397

- Rossi, EC, Beaverstock, JV & Taylor, PJ, 2007. Transaction links through cities: ‘Decision cities’ and ‘service cities’ in outsourcing by leading Brazilian firms. Geoforum 38, 628–42. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.11.005

- Sassen, S, 2001. The global city: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Scholvin, S, 2017. Das Tor nach Sub-Sahara Afrika: Kapstadts Potenzial als Gateway City für den Öl- und Gassektor. ZeitschriftfürWirtschaftsgeographie 61(2), 80–95.

- Scholvin, S, 2019a. Rebalancing research on world cities: Mauritius as a gateway to sub-Saharan Africa. In S Scholvin, A Black, J Revilla Diez & I Turok (Eds.), Value chains in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges of integration into the global economy. Berlon, Springer.

- Scholvin, S, 2019b. Articulating the regional economy: Cape Town, Durban and Johannesburg as gateways to Africa. African Geographical Review. doi:10.1080/19376812.2019.1664915.

- Scholvin, S, Breul, M & Revilla Diez, J, 2019. Revisiting gateway cities: Connecting hubs in global networks to their hinterlands. Urban Geography 40(9), 1291–309. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1585137

- Short, JR, Breitbach, C, Buckman, S & Essex, J, 2000. From world cities to gateway cities: Extending the boundaries of globalization theory. City 4(3), 317–40. doi: 10.1080/713657031

- Sigler, TJ, 2013. Relational cities: Doha, Panama City, and Dubai as 21st century entrepôts. Urban Geography 34(5), 612–33. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2013.778572

- Southey Mauritius, 2019. Welcome to Southey Mauritius. Southey Mauritius, Grand Baie. https://www.southeymauritius.com Accessed 20 February 2019.

- Taylor, PJ, Catalano, G & Walker, DR, 2002. Measurement of the world city network. Urban Studies 39(13), 2367–76. doi: 10.1080/00420980220080011

- Van Grunsven, L & Hutchinson, FE, 2016. The evolution of the electronics industry in Johor (Malaysia): Strategic coupling, adaptiveness, adaptation, and the role of agency. Geoforum 74, 74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.05.011

- Van Meeteren, M & Bassens, D, 2016. World cities and the uneven geographies of financialization: Unveiling stratification and hierarchy in the world city archipelago. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40(1), 62–81. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12344

- Warf, B & Vincent, P, 2003. Global finance and the Arab world: Bahrain as an offshore banking centre. Arab World Geographer 6(3), 165–77.

- World Bank, 2009. World development report: Reshaping economic geography. World Bank, Washington. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5991 Accessed 25 February 2019.

- World Bank, 2017. Doing business 2017: Equal opportunity for all. World Bank, Washington. http://www.doingbusiness.org/~/media/WBG/DoingBusiness/Documents/Annual-Reports/English/DB17-Report.pdf Accessed 6 October 2017.

- World Economic Forum, 2017. The global competitiveness report 2017–2018. World Economic Forum, Geneva. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2017-2018/05FullReport/TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2017%E2%80%932018.pdf Accessed 6 October 2017

- World Maritime News, 2014. MRPL to turn Mauritius into petroleum hub. World Maritime News, n.d. https://worldmaritimenews.com/archives/145251/mrpl-to-turn-mauritius-into-petroleum-hub Accessed 30 April 2019.