ABSTRACT

This article investigates the architectural manifestation required for the establishment of the university as anchor institution in South Africa. Through an historical review of campus architecture and planning, an understanding is gained of the development of current thought associated with the exclusivity of the institution. The insularity of current campus architecture has allowed for seclusion within the knowledge environment. The paradigm of current campus design and architecture within South Africa is analysed as possible informants to design these relevant facilities. Service learning can facilitate the exchange of knowledge to not only contribute to the communities surrounding universities, but add to the research and relevance of our institutions within the urban environment. The exchange of knowledge can become a bridge between town and gown. Through a comprehension of the spatial requirements of such a facility, architecture can contribute to the accessibility, legibility and transparency of the institution.

1. Introduction

A university is a knowledge incubator, where ideas are captured, researched, confirmed or improved upon. It allows others to gain access and add value to ideas. In addition, a university can make critical contributions to economic growth within communities, adding value to a city, not only through this sharing of knowledge gained but also through its role as an anchor institution (Ehlenz Citation2018:76).

High fences and spatial exclusion create physical barriers between the university campus and the urban environment, which contributes to the identity of exclusivity within these institutions (Hendricks & Leibowitz Citation2016). Globally, a dominant concern around urban citizenship and the right to the city (Blokland et al. Citation2015) regards access to amenities and resources as crucial for the sustainable development of cities.

A responsive architectural manifestation and proactive approach to the development of porous boundaries is required to inspire accessibility and transparency of institutions, that may enhance the surrounding area (Sungu-Eryilmaz Citation2009). The scholarship of engagement (Boyer Citation1996) forms an integral part of the exchange of knowledge between students, university staff, and the community. Through the creation of a spatial platform, universities can contribute to the establishment of physical places of belonging and integration, thereby broadening the scope of engagement towards the support of urban revitalisation (Sungu-Eryilmaz Citation2009).

It is the aim of this article to determine what the spatial implication and architectural manifestation should be for an anchor institution to express these values and goals and thereby contribute to shared knowledge systems, resources and urban development. Thematic analysis is employed to understand the framework intentions of the university as anchor institution, the Scholarship of Engagement (Boyer Citation1996), and the evolution of campus design in South Africa within the twenty-first century. Their frameworks, programmes, engagement aims, public accessibility, shared amenities and intentions with regard to these themes are analysed and compared to understand where their aims and goals overlap and where future spatial development goals should aim.

Through an historical review of campus architecture and planning from its inception, an understanding is gained of the development of the current system of thought that is associated with the exclusivity of the institution. The paradigm of current campus design and architecture in South Africa has brought to the forefront what universities can contribute to thier cities and surrounding neighbourhoods and how they can become active stakeholders within the urban landscape. It is the aim of this article to identify a basis from which a theoretical continuum for campus design in South Africa can be established.

2. Anchor institutions

Anchor institutions have a crucial role in the development of the communities and neighbourhoods in which they are situated (Taylor & Luter Citation2013:2). As immobile entities, they are tied geographically to a certain location by ‘a combination of investment capital, mission, or relationships to customers or employees’ (Taylor & Luter Citation2013:7).

Anchor institutions occupy substantial portions of land and have a large presence within society and the city. These include institutions such as universities, hospitals and libraries. They are regarded as social establishments that mediate the intersection of people and localities (Taylor & Luter Citation2013:7). Shek & Hollister (Citation2017) describe the need for the exploration of university social responsibility to promote activities that are ethical, inclusive and beneficial to the public. They emphasise environmental conservation, sustainability and balanced social development; the promotion of welfare and quality of life of people (especially of disadvantaged and vulnerable populations); and a commitment to building a better world (Shek & Hollister Citation2017). Becker and Hesse (Citation2013) state that ‘ … well-integrated campuses have the potential to revitalise surrounding communities, value neighbourhoods and improve on- and off-campus community cohesion’.

One of the purposes of higher education is to produce citizens to serve the community. The intention is that the skills and knowledge gained by the educated person be used to contribute to the community once a student has completed their studies and entered the workforce. Educated citizens should thus contribute to the insurance of human rights; the development of a productive society; and the alleviation of human suffering, which is a matter of both ethical and social concern (Speck & Hoppe Citation2004:3).

3. The scholarship of engagement and community engagement

Ernest Boyer (Citation1996) argued that education must stay relevant to the most crucial matters within societies today. He proposed four models that are interrelated and necessary – referred to as the scholarship of engagement. The four models include the scholarship of discovery; the scholarship of integration; the scholarship of sharing; and the scholarship of application. The scholarship of engagement argues that cities determine our futures, they must therefore focus on the complex problems of urban life, for which there are no simple solutions. Through students engaging and working directly with the community, these shortfalls can be identified. Community engagement within a tertiary setting allows the theoretical knowledge a student has gained to become practice and then move back to theory. This then contributes to the authentication of such theoretical knowledge (Boyer Citation1996).

Within the context of higher education, community engagement can be approached in various ways: community-based research, participatory action research, service-learning, and professional community service. In ‘its fullest sense, community engagement is the combination and integration of service with teaching and research related and applied to identified community development priorities’ (Lazarus et al. Citation2008:61).

The paradigm of thought regarding community engagement has moved away from the community as research objects and as beneficiaries of charity. The intent is for partnership with communities: with mutual benefit for all parties involved. University knowledge can contribute to the resolution of problems identified by communities, while students can simultaneously apply new knowledge they have gained (De la Rey, Kilfoil & Van Niekerk Citation2017:155).

A well complimented university environment can be created through the presence of various forms of scholarship, as put forth by Ernest Boyer (Citation1996), which can include any type of scholar in any field of study. The scholar is engaged if the knowledge is not developed for its own sake, but rather with the well-being of society in mind (Checkoway Citation2013:8).

The university should be a resource for teachers and other practitioners. It should enrich the civic and academic health of practitioners and scholars and be an environment that promotes communication. Speaking and listening to each other can ensure a healthy cultural setting for the growth of the knowledge environment. To this end, places and spaces must be designed where communication can take place. The relationship between universities and communities is a critical success factor and community engagement is a part of the institution’s core business (De la Rey et al. Citation2017:168).

4. The inception of the university

The development of the university tells a story of spatial isolation from the inception of Al-Qarawiyyin University in Fez, Morocco in North Africa (Siddiqi Citation2018) to its development into Europe in 1088, Britain in the 14th century and America in the 16th century. The American model was described by Le Corbusier as an urban unit in itself which formed a self-contained community of individual buildings (Turner Citation1984:32).

The British campus model was established with emphasis on the education and housing of undergraduates and staff, creating a community within itself. The buildings were arranged around courtyards, based on the English tradition of the cloistered monastery with most of the English colleges being found in monastic structures. The courtyard typology of Oxford University led to well defined street edges, optimised use of space and increased security, and an identity of place that is still recognised in Oxford today (Turner Citation1984).

The American model claimed the term campus, which means field in Latin. Harvard, the oldest university in America, was established in a singular building on a plot of land and was the birth of the American university model, the creation of separate buildings in the landscape. Higher education was only considered fully effective when students study, eat, sleep, worship and play together, which required isolation free from any distraction (Turner Citation1984:23).

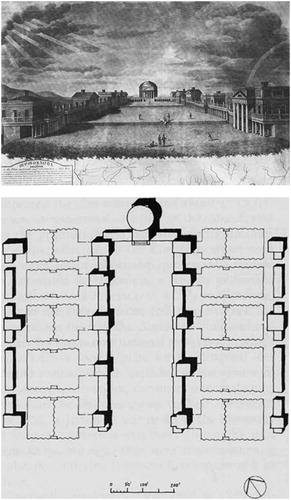

In the eighteenth century the American model of individual building became more structured around a central grand avenue, with two rows of buildings across an open space, facing each other. The University of Virginia (), a Thomas Jefferson design, was based on the use of the central lawn that was regarded as the central village green and lined with five classical houses, called pavilions, with a central focal point the iconic Rotunda, and connected the pavilions with a low colonnaded walkways (Turner Citation1984:59). This model became a popular form and was very influential in American campus design, which also became the model for all historical campus plans in South Africa (Peters Citation2011:78). In the following section, the development of South African campus design will be discussed, with some of the older campuses such as the University of Pretoria clearly influenced by the central lawn with focal building as in the American examples.

Figure 1. University of Virginia Campus. Designed by Thomas Jefferson in 1817 (Turner Citation1984, 23).

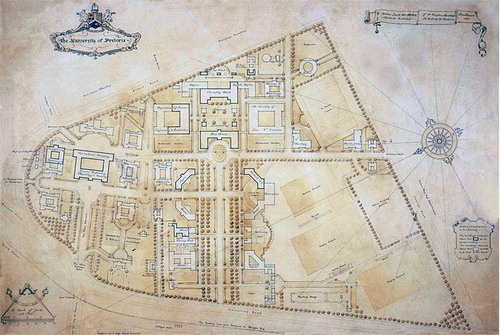

5. The University of Pretoria Main Campus

The University of Pretoria’s main campus in Hatfield () has a rich architectural history that developed over many decades. The planning of the campus resembles the American campus model with the central lawn surrounded by pavilion structures. The focal point is to the end: The Old Arts Building constructed in 1911 (Brink Citation2012:11). The campus was initially part of the urban fabric and the roads on campus could be accessed by the public. As the number of enrolled students increased, development extended to the east of Roper Street, which resulted in a public road running through the campus. In 1993, the campus obtained the city council’s permission to close this road to the public. The first applications for this closure were made during the design of the Humanities building, which was inaugurated in 1977 (Brink Citation2012:19). The fence that isolates the campus from the surrounding urban fabric was erected soon after the closure of the road, thereby departing from the American paradigm shift towards neighbourhood revitalisation (Ehlenz Citation2015).

Figure 2. University of Pretoria Campus Master plan 1930 (Wikiwand Citation2019).

6. Masterplan campuses

6.1. Rand Afrikaanse Universiteit

The monumental endeavour of a masterplan campus was completed in 1975 (Peters Citation2011:42) with the design of the Rand Afrikaanse Universiteit (RAU) in Johannesburg by the Meyer, Pienaar, Smith Partnership in collaboration with Jan van Wijk. The intention was to create a framework with the capacity to accommodate an unknown future: an octagonal layout allowed for extension around the periphery while inhibiting extension to the centre (Peters Citation2011:44). The design sought to achieve monumentality and the creation of a landmark within the city. The former principal of RAU, who had commissioned the design, had wanted the architects to make a statement about the Afrikaner who arrived in the city (Fisher et al. Citation1998:284).

6.2. The Salk Institute of biological studies

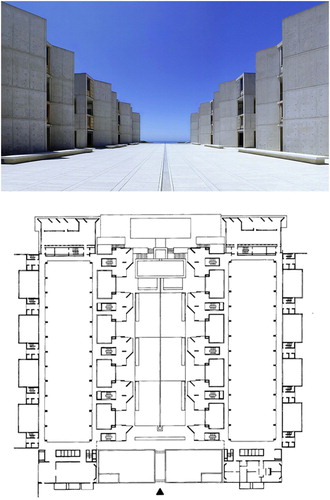

The Salk Institute () was designed by Louis Kahn in 1965 for Jonas Salk (who had discovered and developed the polio vaccine). The inspiration for the model of the campus was the isolated monasteries and cloisters of 13th century Italy. That isolation also served as impetus for the origin of the institution in general as it was intended to nurture Nobel laureates in an isolated environment, away from the distraction of teaching and grant-writing required by conventional universities (Leslie Citation2008:200).

Figure 3. Plan and courtyard view of the Salk Institute (Leslie Citation2008).

The Salk Institute features laboratories with enormous open workspaces. A structural system of pre-cast, pre-stressed concrete trusses and folded plates allows for Kahn’s ‘served’ and ‘servant’ spaces. Services and utilities could be run between the floors. Laboratory spaces could be adapted as required and easily connect with services and utilities (Leslie Citation2008:211).

In contrast to the large open laboratories, Kahn designed intimate studies that occupy the periphery of the courtyard. These he described as the cloister of the courtyard. A sawtooth arrangement ensures that all 36 studies have a view of the Pacific Ocean. These studies were designed for quiet self-study, free from distraction (Leslie Citation2008:212).

As masterplan campuses, the design of both RAU and the Salk Institute sought monumentality. The architecture endeavours to convey the importance of the institution and of the select few allowed to study and conduct research there. Leonard Burkat compared the Salk Institute to a temple of wisdom (Leslie Citation2008:218).

Kahn had originally planned to create a tree-lined garden within the courtyard, but Luis Barragan, a Mexican architect, advised Kahn and Salk to create a plaza with hard surfaces. Salk considered Kahn’s architecture pure poetry and agreed to the plaza without the gardens (Leslie Citation2008:214). The original intention of the architectural plan was to encourage communication and contemplation through the use of the courtyard. Salk conveyed that new generations would use the outdoor space and recognise the architecture as time progressed, but as Leslie (Citation2008:215) puts it: ‘That never happened’ and the courtyard is not a space for staying.

From these brief descriptions, it is evident that several South African campuses until the turn of the century reflected an isolationist approach, either by way of fortified masterplanning or increased security measures such as fences and access control, known as target hardening, thereby effectively turning their back on the surrounding communities. This is in contrast to developments in North America and Europe, where it became increasingly clear that universities could, in fact, become the primary drivers of economic development beyond their borders (Sungu-Eryilmaz Citation2009).

7. A new campus design paradigm in South Africa

It is therefore interesting to note that a new paradigm of campus design emerged in South Africa with the proclamation of two new universities to be built in terms of the Higher Education Act 101 of 1997 by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) in 2013 (Burke & Hodgson Citation2016:21). Ludwig Hansen Architects and Urban Designers were employed to design the urban frameworks for both the Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley and the University of Mpumalanga in Mbombela. From the outset, it was established that the design of the universities had to engage their settings and enable the growth of the knowledge environment (Hansen Citation2016:23).

The principles identified to guide the design of the campus infrastructure and architecture included the integration of the campus with the existing urban fabric – allowing for shared public spaces to facilitate the occurrence of public meetings and events. These principles also incorporated the enablement and mobility of university staff and students through the accommodation of students on campus within a collaborative environment where the exchange of ideas can take place. Lastly, the principles of environmental sustainability had to be included (Hansen Citation2016:23). Distinct urban codes were given in terms of the specific buildings: a perimeter block typology was prescribed with an interface on street level and predetermined courtyard spaces.

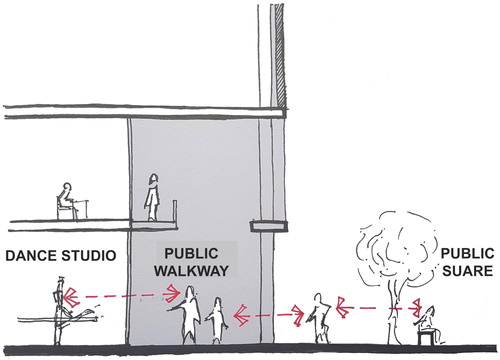

The individual building designs were commissioned by way of a two-phase architectural competition. The DHET expressed the importance of the physical environment and its influence on the quality of both the learning experience and of teaching (Leading Architecture and Design Citation2013). Campus frameworks in South Africa have shifted from an internally focused configuration that promotes a fortified form of the campus to an inclusive and accessible framework where a perimeter block typology for individual buildings on campus provides secure internal courtyard spaces. This allows the architecture to link directly to the public realm and fosters interaction between students and the general public. It therefore contributes to places of meaning and encounters within the urban environment (Thomashoff Citation2016:25) as the campus and city become integrated. On the central campus of the Sol Plaatje University a public square is formed by Campus Buildings 1-3, the library to the south, and a public street to the north (). There is a mixed-typology building, with classrooms, lecture halls, auditoriums, a health- and wellness centre and offices, to the east. A student residential building captures the public space to the east.

Retail spaces have been allocated on street level, although most of the spaces are still vacant (except for a dance studio and a laundromat). As the intention is for retail to become an activator of the public edge, Campus Building 3 (by Wilkinson Architects) has a hierarchy of publicness to privacy from the ground to the higher levels (Thomashoff Citation2016:25). The square is also activated by a semi-permanent basketball court that is well-used by students.

The campus layout has a rigid spatial framework that endeavours to regenerate the urban fabric with shared space, which served as a driver for the campus plan. Multifunctional spaces allow for restructuring, depending on academic needs. The architecture seeks to promote inclusiveness that is relevant and engaged with the setting in an effort to integrate the development of knowledge into the surrounding community (Hansen Citation2016:21-23). The architecture of this Sol Plaatje University campus responds appropriately to the framework and fits the context (Thomashoff Citation2016:28).

In contrast to the Sol Plaatje University, the University of Mpumalanga also established by DHET in 2013, is located in a more rural setting (Hansen Citation2016:24). This inhibits the potential to engage the city of Mbombela (Nelspruit), and a valuable contribution has thus been missed. The university still seeks to impact the skills development of the local community and actively contributes to its economic development through the construction phases of the individual buildings (Hansen Citation2016:21–23). Such economic impact and considerations are a common thread in the Scholarship of Engagement, anchor institutions, and the frameworks of existing and new campuses (Taylor & Luter Citation2013 Hansen Citation2016; Dewar & Louw Citation2017;; Ehlenz Citation2018).

Dewar & Louw (Citation2017, 29) stated that the framework for the development of a university campus enables debate at two levels. Firstly, the academic function of the university must resonate with its spatial form. Secondly, the normative performance qualities the design seeks to achieve must be expressed. This then clarifies both what the framework seeks to achieve and how well the design achieves these qualities.

8. Method

The research aimed to establish the spatial articulation required for university campuses to be relevant to their settings and manifest in ways that are aligned with the goals of the institution as anchor in society and within our cities. Thematic analysis, a qualitative research method, was employed within an interpretive research paradigm, to allow for a flexible approach to the data collected (Braun & Clarke Citation2006).

The study is an overview of architectural precedents followed by a normative argument, typical of the studies required for the framing of architectural research (Groat & Wang Citation2013). Precedents (Sol Plaatjie University and University of Mpumalanga) have been identified within the current paradigm of campus design and architecture in South Africa as a baseline to determine a model for future spatial development of university campuses.

The data collection criteria were based on current research on anchor institutions and their development goals and how these goals have been implemented spatially or in the physical environment. Older South African campuses with open edges have not been included in the discussion, as they have not engaged intentionally with a process of target hardening over time. From the research, common themes were identified between anchor institutions, the scholarship of engagement, design frameworks for campus planning & architecture before 2013 and after 2013. The year 2013 became significant because a shift in the frameworks published is noted from a paradigm of exclusivity to inclusivity, where the spatial relationship to the public sphere has become a main concern and the contribution to the urban environment has become prominent. Design frameworks for campuses currently under construction in South Africa, namely Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley, Northern Cape and the University of Mpumalanga in Mbombela were selected as examples. These universities were selected on the basis of their contribution to contemporary architectural discourse in South Africa, in which important convergences can be seen towards a physical manifestation of the scholarship of engagement. The comparisons are presented in (below):

Table 1. Comparison between spatial and strategic frameworks in SA campuses before and after 2013.

9. Findings

The aspirations of anchor institutions in the USA have manifested on a spatial level: urban landscaping is promoted for the university campus to become a connective corridor (Taylor & Luter Citation2013). This is also fundamental to the Sol Plaatje campus framework. Urban designer Ludwig Hansen (Citation2016) described the campus framework as a central pedestrian spine promoting pedestrian transport. These spaces promote informal learning and counter the exclusivity of previous planning frameworks.

The main purpose of campus architecture is not only to accommodate formal educational processes within lecture halls and laboratories (Thomashoff Citation2016:27) but also to define and form public spaces to allow for informal learning. Buildings on campus must allow for surveillance over these public spaces to contribute to the safety of all who use it, in keeping with the principles of Crime Prevention through Environnmental Design (CPTED), which . aims to ‘reduce the causes of, and opportunities for, criminal events and address the fear of crime by applying sound planning, design and management principles to the built environment’ (Kruger Citation2020: 3). Typically, when designing in this way, considerations would include physical planning at a strategic level, detailed design of access points, routes and public edges and the management of the system in a preventative way rather than relying on barricades and security forces. A commonality noted in anchor institutions, with old or new campus frameworks, is the promotion of pedestrian- and non-motorised transport. Such paths must be well-lit at night and can form a visible connective element throughout the campus (Taylor & Luter Citation2013; Hansen Citation2016).

Certain functions, such as sports facilities and retail spaces within a university can contribute to the direct engagement of both the university as anchor and the community. Placing these functions on the edge of a campus enables sharing and interaction (Dewar & Louw Citation2017:30). These amenities also ensure that activity is drawn to the public spaces.

Architecture should contribute to an identity of place. The university campus has meaning bound in the human experience of place and the environment; it should therefore be an unimposing landmark and not an artefact. The spaces between buildings should become more important than the buildings themselves (), while the housing of students, on- and off campus, can contribute to a lively culture of place (Hansen Citation2016:2123).

Figure 5. Sol Plaatje University public square Building CX003: Analysis of the edge condition in relation to the public square. Interaction is established between a dance studio and the public walkway, which creates a successful edge condition that also interacts with the public space.

In the proposed frameworks, nature becomes a place-making element, such as the attenuation of rainwater on surface that contributes to the creation of sensual spaces. Strategic views should be enhanced, and an atmosphere of surprise and wonder be created to invoke curiosity (Dewar & Louw Citation2017:30).

The analysis establishes that anchor institutions have a spatial responsibility to the community in which they are situated. As an anchor institution is a large occupier of urban land, real estate development forms part of the strategic framework. Within the framework, mixed-use typologies are important to ensure the presence of activity nodes and public spaces. Accessible green space combined with security and well-lit pedestrian paths to ensure safety are important in the creation of healthy urban environments, as described in the CPTED principles (Kruger Citation2020). Spaces where people feel safe will be well-used spaces.

The analysis of the scholarship of engagement shows the establishment of an office to administer student and faculty engagement with the community as the only spatial requirement. Spatial exploration in this case is left wanting and more investigation is required to establish the requirements for the creation of a platform for interaction that aims to benefit both the community and institution.

The establishment of two new universities in South Africa awakened the local design community to the potential of communicating institutional values through the integration of university buildings into the surrounding neighbourhood.

Historically, the development of campus plans had isolation and seclusion as principles, but integrated pedestrian pathways and meeting places strengthen the social function of the city space. (Gehl Citation2014:6) describes these social meeting places as spaces that contribute towards the aims of social sustainability and an open democratic society. Architecture can be instrumental in an existing institution’s spatial contribution to society. This spatial contribution can be through the creation of communal and interactive spaces on the edge that allow for intersection with the surrounding environment while maintaining a safe and secure environment for staff, students, and the public. A sense of place can be created when the city dweller is socially satisfied (Allers & Breytenbach Citation2015:28).

Gehl (Citation2014:75) describes the edge as a really good place to be in a city. It should be the intention of campus design that, through learning, students can positively contribute to a community, while they gain valuable insight into the realities of the urban dweller in South Africa. This is instrumental as an invaluable knowledge transfer from the institution to the public and the public to the institution. Where a building edge meets the street and where doors exist within this edge, points of exchange develop – activities move from the inside to the outside and there is interaction with the city (Gehl 2013:75).

The paradigm of campus planning must therefore be altered to regard spatial interaction as an important factor in the creation of the desired connection between town and gown. The polarities of campus and surrounding urban life can become a catalyst for the creation of vibrant urban public space. This space can be the intersection between the current paradigm of isolated tertiary institutions and the creation of a relationship with the surrounding communities. The high fences currently around many university campuses create undefined street edges with no landmarks. This target hardening causes the street edge to become a monotonous space without identity (Kruger Citation2020).

In the image () Jan Gehl illustrates how certain conditions can invite or repel the city dweller. Gehl (2013:75) describes the edge as the place where the building and city meet. The treatment of edges has a direct influence on the character of life within the city. The edge defines space and can contribute to comfort, security and organisation. Weak edges, or no edges, make for an impoverished city, as well-defined edges offer a level of protection, privacy and shelter to pedestrians that use the city (Allers & Breytenbach Citation2015:31).

Figure 6. Diagrams depicting conditions that invite – or repel when seeing and hearing contacts (Gehl Citation2014, 237).

The edge is not only a place where exchanges take place but also a staying zone. A building’s edge provides protection at peoples’ backs – knowing that no one can approach them from behind, people can enjoy the view of the city and other people (Gehl 2013:75). ‘All meaningful social activities, intense experiences and conversations need to take place in spaces where people can walk, sit, lie, or stand’ (Allers & Breytenbach Citation2015:33).

The edge is also a zone for experience. The building edge on the ground floor is the most important element to this experience. For example, vertical elements in a building facade create rhythm. At an ordinary walking pace of 80 s per 100 m a person travels approximately 5–6 m every 4–5 s - this determines the interval at which the average human requires sensory stimulation (Gehl 2013:76). The design of building facades can thus influence how the urban dweller experiences the city. If stimulating detail is created the walk feels shorter and is more enjoyable. When monotonous fences and boundary walls line the street, the walk feels long (Gehl 2013:76).

Christopher Alexander (Citation1979) described practical patterns to achieve community connection within the architecture of a university campus. What defines campus architecture are the spaces and movement between buildings and the various ways in which these spaces can be inhabited. Such spaces should allow not only circulation and movement but also rest, social engagement and collaboration. The intersection between quiet and busy places should be mitigated by intermediary spaces, which then become places that exist in their own right. To become a generator of form and place making, intermediary spaces should also mitigate the interior and exterior, public and private spaces, and the spaces for leisure and spaces work. A space can never be alive if the edge fails.

Universities have formed the identity they have today as a rite of passage. At the inception of the university as a place of learning (in the first millennium), it was an isolated environment only accessible to a select few. Victor Turner (Citation1969) defined liminality as the separation from a fixed or constant and known state into the limen (threshold in Latin) or rite of passage to emerge on the other side, again in a constant state, but one with new obligations and rights.

Peter Hasdell (Citation2016:2) explained that liminal bodies have spatialities and autonomies created by complex coincidence and the negotiation of diverse factors. The resulting boundaries become contested sites where differences manifest: civil protests serve as a tangible indicator of collective disagreement and a desire for change within the community (Hasdell Citation2016:1).

The creation of positive public spaces on these boundaries can establish a new gateway to the campus and enable economic, social and cultural development. The design of shared courtyards and public spaces may foster appreciation for good environments and become a platform for learning within the community (Hansen Citation2016, 24).

10. Conclusion

This article advocates for the necessity to include the spatial aspirations of the university as anchor institution in the future planning and frameworks of South African tertiary institutions in keeping with Boyer’s (Citation1996) sentiment: ‘ … great universities simply cannot afford to remain islands of affluence, self-importance, and horticultural beauty in seas of squalor, violence and despair’. The economic, social and spatial implications of these institutions on society must be considered on all levels to ensure sustainable development of our cities. As concluded by Sungu-Eryilmaz (Citation2009, 6), there is ample evidence to indicate that ‘ … land uses at the campus edge have become a crucial element in both the physical and socio-economic characterof cities and neighbourhoods’. The urban citizen has the right to participate and make full use of urban public space (Blokland et al. Citation2015). Anchor institutions have the resources and means to invite the urban citizen to actively participate in these spaces. The scholarship of engagement ensures a direct interaction between the community, faculty and students. The role of universities within society is changing and evolving from an inward-looking environment only accessible to a select few, to institutions with the responsibility of contributing to their urban environments (Sungu-Eryilmaz Citation2009; Becker & Hesse Citation2013; Ehlenz Citation2015) - the Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley is testimony to this requirement.

The architectural resolution of the campus edge is therefore of great importance (Gehl Citation2014), becoming the physical manifestation of a porous boundary through which universities ‘integrate neighbourhoods into their campuses’ (Ehlenz Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alexander, C, 1979. Timeless way of building. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Allers, A & Breytenbach, A, 2015. Arcades revisited as urban interiors in a transformed city context. Image & Text 26:27-46. University of Pretoria. http://www.imageandtext.up.ac.za/images/files/issue%2026/IT_26_new.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018.

- Becker, T & Hesse, M, 2013. Building a sustainable university from scratch: Anticipating the urban, regional and planning dimensions of the Cite des Sciences Belval. In A Konig (Ed.), Regenerative sustainable development of universities and cities: The role of living laboratories. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, 254–273.

- Blokland, T, Hentschel, C, Holm, A, Lebuhn, H & Margalit, T, 2015. Urban citizenship and the right to the city: The fragmentation of claims. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1111/1468-2427.12259/full. Accessed 12 June 2017.

- Boyer, E, 1996. The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach 1(1), 11–20. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1097206. Accessed 23 July 2018.

- Braun, V & Clarke, V, 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77–101. https://psychology.ukzn.ac.za/?mdocs-file=1176. Accessed 23 July 2018. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brink, B.N. 2012. A survey of buildings designed by Sandrock architects for the University of Pretoria and the University of South Africa. Department of Civil and Chemical Engineering, University of South Africa. . http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/5806 Accessed 12 June 2017.

- Burke, M & Hodgson, S, 2016. Strategic context of the new universities - from concept to implementation. Digest of South African Architecture 21, 20–37.

- Checkoway, B, 2013. Social justice approach to community development. Journal of Community Development 21(4), 472–486. https://www-tandfonline-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1080/10705422.2013.852148. Accessed 18 July 2018.

- De la Rey, C, Kilfoil, W & Van Niekerk, G, 2017. Evaluating service leadership programs with multiple strategies. In D Shek & R Hollister (Eds.), University social responsibility and quality of life. Springer Singapore, Singapore. 55–174.

- Dewar, D & Louw, P, 2017. Issues relating to university planning and design part 1. Journal of the South African Institute of Architects 88, 25–29.

- Ehlenz, M, 2015. Anchoring communities: The impact of University interventions on neighbourhood revitalization. Dissertation: University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons.

- Ehlenz, M, 2018. Defining university anchor institution strategies: Comparing theory to practice. Accessed 17 July, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/l/10.1080/14649357.2017.1406980?scroll=top&needAccess=true.

- Fisher, RC, Le Roux, S & Mare, E, (Eds). 1998. In architecture of the transvaal. University of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Gehl, J, 2014. Cities for people. University of Simon Fraser Library, Burnaby, BC.

- Groat, L & Wang, D, 2013. Architectural research Methods. 2nd Ed. Johan Wigley and Sons, New jersey.

- Hansen, L, 2016. Campus design and architectural development for Sol Plaatje University and the University of Mpumalanga. Digest of South African Architecture 21, 23–27.

- Hasdell, P, 2016. Liminal urbanism, The emergence of new urban ‘states’. International Conference: From Contested Cities to Global Urban Justice, Stream 1 Article no 1-003. http://contested-cities.net/working-papers/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2016/07/WPCC-161003- HasdellPeter-LiminalUrbanism.pdf. Accessed 28 April 2017.

- Hendricks, C & Leibowitz, B, 2016. Decolonising Universities isn’t an easy process – but it has to happen. https://theconversation.com/decolonising-universities-isnt-an-easy-process-but-it-has-to-happen-59604. Accessed 2 April 2017.

- Kruger, T, 2020. Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED). Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. https://www.saferspaces.org.za/understand/entry/crime-prevention-through-environmental-design-cpted. Accessed 7 January 2020.

- Lazarus, J, Erasmus, M, Hendricks, D, Nduna, J & Slamat, J, 2008. Embedding community engagement in South Africa higher education. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, Sage Journals. Accessed 17 July, 2018. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1746197907086719.

- Leading Architecture & Design, 2013. Winning architects and architectural designs in Sol Plaatje design competition announced. https://www.leadingarchitecture.co.za/winning-architects-architectural-designs-sol-plaatje-university-design-competition-announced/. Acessed 12 May 2018.

- Leslie, S, 2008. A different kind of beauty: Scientific and architectural style in I. M. Pei's Mesa Laboratory and Louis Kahn's Salk Institute. Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 38(2), 173–221. doi: 10.1525/hsns.2008.38.2.173

- Peters, W, 2011. Men are as great as the monuments they leave behind: Wilhelm O Meyer and the (Rand Afrikaans) University of Johannesburg, Kingsway campus. South African Journal of Art History 2, 68–80. Accessed 2 April, 2017. http://journals.co.za.uplib.idm.oclc.org/content/sajah/26/2/EJC94130?fromSearch=true.

- Mtawa, N, Fongwa, S & Wangenge-Ouma, G, 2016. The scholarship of university-community engagement: Interrogating Boyer’s model. International Journal of Educational Development 49, 126–133. Accessed 23 July, 2018. https://www-sciencedirect-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0738059316300074. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.01.007

- Shek, D & Hollister, R, 2017. University social responsibility and quality of life. Springer Singapore, Singapore.

- Siddiqi, R, 2018. Oldest library of University of Al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, Morocco. Pakistan Library and Information Science Journal 49(3), 69–73.

- Speck, B & Hoppe, SL, 2004. Service-learning. Praeger, Westport, CT.

- Sungu-Eryilmaz, Y, 2009. Town-gown collaboration in land use and development. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge.

- Taylor Jr., HL & Luter, G, 2013. Anchor institutions: An interpretive review essay. Anchor Institutions Task Force, Buffalo, NY.

- Thomashoff, F, 2016. Building CX003: Sol Plaatje University, Kimberley. Journal of the South African Institute of Architects 82, 24–28.

- Turner, PV, 1984. Campus, an American planning tradition. 1st ed. Architectural History Foundation, New York.

- Turner, V, 1969. ‘Liminality and communitas’ in ‘The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure’. Aldine Press, Chigago. 94–113.

- Wikiwand, 2019. University of Pretoria Campus Plan. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/University_of_Pretoria. Accessed 19 August 2019.