ABSTRACT

This study explores the motivations for rural tourism and segments its market based on the push and pull motivational forces by drawing largely from international tourists visiting villages on the slopes of Kilimanjaro Mountain in Tanzania. By applying questionnaire survey and critical segmentation algorithm, the study provides empirical evidence that rural tourists in African villages are motivated by nostalgia for rural cultural life. Other motivations include relaxing with relatives and friends, learning about local farming methods, socialising with the villagers, enjoying nature and contributing to the community. The clustering of the motivations generated the four segments of multi-experiences, authenticity-learners, relaxing with friends and relatives, visiting farms and nature seekers and casual segments. The study argues that rural tourism market is heterogeneous and plural. Recommendations for practitioners and for future research are provided.

1. Introduction

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), tourism taking place in the countryside, also known as rural tourism, has conventionally focused on natural attractions at national and world heritage sites. Today, however, rural tourism integrates the local culture and heritage maintained by people in the villages, thanks to a maturing tourism market and changes in tourists’ preferences (Timothy & Nyaupane, Citation2009). Rural tourism can revive and diversify rural economies, conserve the local heritage and revitalise traditional villages that have suffered from the effects of urbanisation and modernisation (Anderson, Citation2015; Gao & Wu, Citation2017). In Tanzania, for instance, the development of rural tourism in villages, dubbed come and visit the people began in 1995 in the form of the Cultural Tourism Programme (CTP) with five villages (Salazar, Citation2012). Due to their significant contribution, in 2002, CTPs were heralded by the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) as good sustainable development practice by Tanzania (Salazar, Citation2012). Currently, there are about 76 registered CTPs and 116 emerging Cultural Tourism Initiatives in the country (TTB, Citation2019).

Despite many efforts to develop rural tourism by focusing on the local heritage, villages still receive fewer international tourists than the national parks in their vicinity. In Kilimanjaro, while about 50,553 tourists visited Kilimanjaro National Park in 2018, only 0.8% of them visited villages in the mountain’s vicinity (URT, Citation2019; CTP coordinator, personal communication, August 2019). In this regard, developers and marketers of village tourism do not have the information they need to develop appropriate strategies for marketing this kind of tourism (Kayat, Citation2014; Mgonja et al., Citation2015; Lwoga, Citation2019).

For the marketing of rural tourism to be effective, it is necessary to find out who visits a place and why, so that they can be placed in the appropriate market segment, which would enable specific programmes to be designed for tourists using the usual demographic variables of age, sex, income and education (e.g. Cha et al., Citation1995). However, these do not reveal their personality traits, interests, what is important to them and what would motivate them to visit a certain place (Nyaupane et al., Citation2006). Moreover, the power of gender, age and wealth that is predicted to affect purchasing behaviour is markedly situation-dependent, and indirectly related to purchase intentions, which is why marketers agree that the most effective predictors of tourists’ visiting behaviour are their motivations for choosing a destination (Goeldner & Ritchie, Citation2003).

Except for Agyeiwaah (Citation2013), Rid et al. (Citation2014), Nduna & Zyl (Citation2017), most studies on rural tourism focused on natural and ecotourism settings in America, Asia and Europe, and therefore cannot guide practitioners and policy-makers in developing appropriate marketing strategies for SSA, where local heritage assets are associated with a mixture of indigenous and colonialist accounts of traditional practices (Timothy & Nyaupane, Citation2009). Consequently, the reasons why tourists would want to visit villages in SSA are likely to differ from why they would visit places in other regions. European and North American rural places are often preferred for their romanticised rurality, natural setting and beautiful surroundings (Lane & Kastenholz, Citation2015). Although this may be true of African villages, what could attract visitors would be the traditional lifestyle of people and their heritage (Mgonja et al., Citation2015). In this regard, while some studies consider that the tranquillity of rurality and paradise-like settings in which to relax and escape from the world outside is what draws visitors (Cawley & Gillmor, Citation2008; Sidali & Schuls, Citation2010; Eusebio et al., Citation2017), others consider that rurality, in terms of the culture and traditional way of living, is important for attracting visitors, especially those who want to learn, socialise and experience an authentic way of life (Agyeiwaah, Citation2013; Perkins et al., Citation2015; Huang et al., Citation2016). However, more understanding on this subject is needed, which this study seeks to provide.

This study contributes to the above debate on tourist motivations for visiting rural places by questioning international tourists visiting villages on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, who were segmented into clusters, according to what were the push and pull factors. The results provide village tourism coordinators and marketers with insights into the rural tourism market, which assist them in planning appropriate marketing strategies, and give them a greater understanding of why some people would be attracted to rural tourism in the SSA village context.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Heritage tourism and rural tourism

Heritage refers to what we inherited from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations, including the natural and cultural, as well as the tangible and intangible assets of significance (Timothy & Nyaupane, Citation2009). Some people visit heritage places further away from where they live for the purposes of leisure and education, whereas others are not involved in any activity but just want to visit a heritage site are engaged in heritage tourism (Rogerson & van der Mwere, Citation2016). Heritage tourism has traditionally focused on majestic buildings, such as castles, cathedrals and stately homes. Today however, it is widely acknowledged that visiting places that depict the lives of ordinary people, such as farmers, factory workers and fishermen, is part of heritage tourism (Timothy & Boyd Citation2006).

A holistic model of heritage tourism produced by Timothy & Boyd (Citation2006) shows that heritage tourism traverses a mixture of landscapes and settings (pristine natural to urban artificial). In this regard, heritage tourism could become part of rural tourism, if it were to focus on the past and contemporary and tangible and intangible cultural heritage in rural, suburban and urban settings. This study focuses on rural tourism.

2.2. Rural tourism and its motivation

Rural tourism is simply a subset of heritage tourism, which takes place in the countryside (Lane & Kastenholz, Citation2015). What is central to defining it is the notion of rurality, which is characterised by low population density, small widely scattered settlements, natural uncultivated or semi-cultivated land and/or land that is farmed, and the traditional social structure and way of life (Lane & Kastenholz, Citation2015). Rural tourism is multi-faceted, as it encompasses farm-based holidays, special-interest nature holidays and ecotourism, walking, climbing, riding and adventure holidays, hunting, sports activities, and health and ethnic tourism.

Motivation refers to the driving force which initiates, guides and maintains goal-oriented behaviours (Klenosky et al., Citation2007). The push and pull theory posits that push (intrinsic) and pull (extrinsic) factors influence a person to participate in a particular tourism activity (Klenosky et al., Citation2007). Regarding the push factor, the theory posits that an individual participates in a tourism activity because she/he is pushed by the desire to satisfy a need through participating (Klenosky et al., Citation2007), such as the need to travel to correct the cultural and socio-psychological disequilibrium that a person feels (Park & Yoon, Citation2009). Concerning that pull factor, the theory posits that an individual participates in a particular tourism activity because she/he is pulled by what the destination has to offer in terms of natural and cultural attractions and activities that are likely to be pleasurable (Lwoga, Citation2019). The importance of the theory is that it represents the two aspects of demand and supply inherent in tourism, namely the needs and desires of tourists and what attractions tourism operators can offer to meet those needs.

Early empirical studies on rural tourism motivation (e.g. Cawley & Gillmor, Citation2008) focused on the postmodern anti-urban sentiment and dreams of a rural paradise, or nostalgia for happier times in the countryside some time ago (Cawley & Gillmor, Citation2008; Sidali & Schuls, Citation2010; Eusebio et al., Citation2017), as well as for the culture and traditional way of life that is fondly remembered (Park et al., Citation2004; Perkins et al., Citation2015; Huang et al., Citation2016). The search for a romantic rural lifestyle is becoming an increasingly popular special-interest pursuit (Eusebio et al., Citation2017), although, according to Sidali & Schuls (Citation2010) and Eusebio et al. (Citation2017) not among rural tourists. The need to relax and get away from it all is another reason for visiting rural localities (Park et al., Citation2004; Pesonen, Citation2012; Huang et al., Citation2016). However, the need to socialise in terms of host–guest interactions is considered more important than relaxing and escaping (Agyeiwaah, Citation2013; Lwoga, Citation2019).

Regarding the pull factors, what is clear is that visitors seeking rurality in terms of escaping to paradise would be attracted by the natural environment, while those seeking the traditional way of life would be attracted by meeting village people and learning about their culture (Lane & Kastenholz, Citation2015). In this respect, recent studies have contended that tourists’ motivations are heterogeneous (Carvache-Franco et al., Citation2019), which means that the marketing of rural tourism should be based on the fact that there can be various market segments.

2.3. Rural Tourism Market Segmentation

Market segmentation is dividing a market into segments that are homogeneous and exhibit similar purchasing behaviours. Past studies have revealed the market segment of rural tourism. The dominant segment structure seems to be a three-to-five-cluster. In Portugal, Almeida et al. (Citation2014) found that some tourists value the peaceful and relaxing rural atmosphere rather than the rural way of life, others prefer to be with their family and friends in a rural setting, while there are those who have a ‘want-it-all’ attitude and are determined to take part in all the activities on offer. In the UK, rural tourists were segmented into relaxation (dominant segment), fresh air, peace and quiet, and fitness and good health (Countryside Commission, Citation1995). In France, FNSEA (Citation1989) identified the segments of calm and tranquillity, relaxation, greenery and pure air. In USA (Indiana rural festivals), Li et al. (Citation2009) found those whose motive was to escape rather than join in the festival activities, followed by those travelling with the family, and those who love social gatherings and going to festivals.

In Asia, Park & Yoon (Citation2009) found the dominant segment was relaxing with the family. Other segments were passive tourists with little interest in anything, those who long for excitement and so will partake in all that is happening, and those who like socialising. A study in South Korea identified the segments of escaping from everyday life, being together and learning as a family, self-actualization, accessibility, refreshment and activity (Song, Citation2005).

In Africa (Gambia), Rid et al. (Citation2014) found multi-experiences, heritage and nature, authentic rural experience and learning and sunbathing on the beach. Nduna & van Zyl (Citation2017) in Mpumalanga (South Africa) found two segments, namely, those wanting to escape to a peaceful and pleasant environment, and those interested in learning about rural culture and traditions. Research in Ghana by Agyeiwaah (Citation2013) found that the segments of interacting with local folk, enjoying authentic local culture, finding out about their way of life and experiencing Ghanaian religious life. The results of Lwoga’s (Citation2019) study on German residents in Tanzania as potential tourists were similar to those of Agyeiwaah (Citation2013) in terms of segments, which were socialising, authenticity, learning new things and sharing the economic ethos.

Overall, the literature indicates that environmental features and their psychological benefits dominated the motive to travel in Western Europe and North America. As regards tourism in Asia and Africa, the segments of learning about traditional culture, authenticity, relaxing in a peaceful location and socialising were found to be important. The significance of the well-preserved African natural environment, where most villages are located, cannot be over-emphasized, according to Nduna & van Zyl (Citation2017). Interestingly, the segment of ‘want-it-all’ appears to be common, thereby reflecting the heterogeneity of the rural tourism market across the continents. In addition, the debate on nature versus traditional culture, and relaxation and escape versus socialisation as being important reasons why people visit rural places is still ongoing. Focusing on tourists visiting villages in the context of SSA, this study seeks to contribute to this debate.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

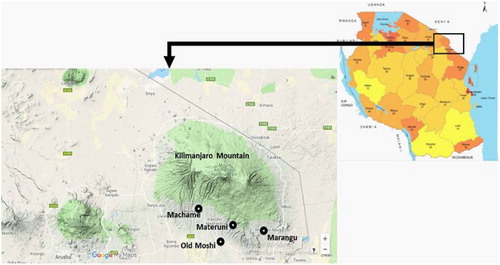

An exploratory cross-sectional survey was conducted in Materuni, Old Moshi, Machame Nkweshoo and Mamba and Marangu villages located on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania (). The four villages were selected randomly from the Tanzania Tourist Board’s (TTB) list of 12 villages with cultural tourism potential (CTPs) in Kilimanjaro region (TTB, Citation2016). Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa at 5,895 metres high, has been declared a national park. Indeed, the popularity and attractiveness of the mountain means that the villages on its slopes are a potential tourist market. (Insert Here)

The villages are rich in terms of natural attractions, including waterfalls, the scenic beauty of the peaks of Mount Kilimanjaro and its associated landscape and biodiversity. These are traditional villages where the Wachagga farm on a small scale, cultivating coffee, vegetables, maize and bananas, and keep livestock (zero-grazing) such as cattle, pigs and goats. Coffee is cultivated using the local hand hoe and organic manure from livestock, and is processed traditionally. The villages are rich in terms of history and heritage. In Old Moshi Village, the history of the Chief of Wachagga named Mangi Meli is well preserved (). The traditional way of life way, including their relics, stories and legends, taboos, traditional food and drink and traditional houses, including the Chagga underground tunnels (dwellings during tribal wars) in Marangu and Machame Nkweshoo villages are well maintained. A visit to a live museum in Marangu village would be a great tourist attraction, because tourists would have the opportunity to learn about traditional healing and medicine, visit the local blacksmith, watch traditional dances and to be invited into their traditional homes. They would also have the opportunity to go for walks near the villages (). In addition, there are old German colonial buildings and graves, and the battlefield where the Germans and Chagga communities fought each other.

(Insert Here) (Insert Here)

3.2. Sample and Sampling Procedures

The target population were international tourists visiting villages on Mount Kilimanjaro. Due to the absence of accurate statistics on tourist arrivals in villages, the study depended on the coordinators of CTPs to estimate total annual arrivals. In 2018, CTPs in Kilimanjaro region received about 5000 tourists (personal communication with CTP coordinators in Kilimanjaro, August 2019). With reference to Krejcie & Morgan (Citation1970), 357 tourists are statistically representative of the population. Random sampling was used to select tourists, whereby at each village entry point, the CTP office, the CTP coordinator and appointed guide handed out a self-administered questionnaire to tourists who agreed to participate. In this way, 390 questionnaires were handed out, 375 were collected and 360 were useful for analysis, making a good response rate of 92.3%.

3.3. Data Collection Method

The questionnaire was designed based on an extensive review of the literature. Measurement items were adopted from Rid et al. (Citation2014), Nduna & van Zyl (Citation2017), and Lwoga (Citation2019). Some 56 items were generated and reviewed by an expert from the University of Dar es Salaam and two CTP coordinators. It started with tourism features that were measured by their importance on a 5-Point Likert Scale, followed by the category of travel behaviour and demographic variables. The questionnaire was pilot-tested with ten international tourists visiting Materuni village in August 2019. After reshaping and rewording some of the measurement items, the questionnaires were administered in September 2019, which was the beginning of the peak tourist season in Tanzania.

3.4. Data Analysis

Several analytical procedures were followed. First, descriptive statistics were applied to describe the sample based on demographic and travel characteristics. Second, principal component analysis (PCA) was run with varimax rotation to identify the underlying motivational dimensions or factors. Cronbach’s Alpha test was applied to check for reliability. Third, factor-solution was used as composite variables in the cluster analysis in order to identify homogeneous segments. In this regard, a combination of hierarchical and non-hierarchical (k-means) methods was employed as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2014). The data was analysed to identify a preliminary set of solutions, using the hierarchical clustering procedure and Euclidean distance to measure the similarity between cases. In addition, the frequently used cluster algorithm known to produce stable and interpretable results, that is the Ward method, was employed to maximise within-cluster homogeneity. The criterion of the relative increase in the agglomeration coefficient was used to support cluster solution. Fourth, ANOVA and post-hoc analyses were employed to test whether all motivational factors similarly contributed statistically to differentiating the segments. The Scheffe post-hoc analysis was done to see whether there were any differences between clusters with respect to each of the factors. Finally, each segment was cross-tabulated with demographic and travel behaviour characteristics for profiling.

4. Results

4.1. Sample profile

The study involved respondents who were tourists visiting Materuni village (38.4%), Mamba and Marangu (30%), Old Moshi (18.3%) and Machame Nkweshoo (13.3%). They were relatively equally distributed in terms of sex and education (). They were young and middle-aged, as 72% of the tourists were between 18 and 49 years old, but only 28.1% were 50 and over. They had a relatively high average monthly income of more than 3000 US$ per month. In terms of travel characteristics, they exhibited the country’s (Tanzania) conventional over-dependence on Europe (62.3%) and North America (19.7%), with 9.5% from Asia. The majority had their visits to villages organised by tour operators (58.1%), and spent at least one full day in the villages (60.6%), while 40.9% were less frequent visitors to villages (once in a few years). In terms of source of information about the villages, the majority obtained it through word-of-mouth (40.4%), or from a tour operator (31%), the internet and social media (28.6%).

Table 1. Demographic and travel characteristics (N = 360).

4.2. Principal component analysis (PCA)

Exploratory factor analysis, using PCA, was conducted on the important ratings of 56 motivational items. The first varimax rotation resulted in a factor solution with 15 cross-loading items and 4 isolated items, which were dropped in subsequent runs (Hair et al., Citation2014). The final rotation resulted in an eight-factor solution with eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining 68% of the total variance in the data. A visual check on communalities showed that all the values were 0.5 and above as proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2014). A Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin measure yielded 0.826 and Bartlett’s statistically significant test of sphericity yielded 4635 (p < 0.001), showing that the distribution values for measuring motivation components were adequate for PCA. The rotated factor matrix showed that all factor loadings related to only a single factor in each case. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.66–0.88, showing that the factors are reliable (see ).

Table 2. Factor analysis results.

The eight factors represent the specific reasons why tourists visit rural villages. The first factor, named the nostalgia for rural cultural life, exhibited the most variance (25.66%) with a reliability coefficient of 0.88 in the data (). This dimension contains eight items. The first was discovering the traditional way of life. The relatively large proportion of the total variance explained by this factor indicates that finding out about the traditional way of life is one of the main reasons why international tourists visit rural villages. The second item, named relaxing with family and friends (accounting for 13.32% of variance in the data), focuses on resting, relaxing and being regenerated, and having fun with family and friends. The third item labelled learning (accounting for 7.22% of variance in the data) summarises seven items relating to tourists’ curiosity about life in rural villages and the desire to learn more. The fourth item called local farming (accounting for approximately 6.10% of variance in the data) relates to the desire to learn about farming methods, especially how coffee is farmed in local plantations.

The fifth item labelled socialisation (accounting for 4.88% of variance in the data) focused on the interaction between the tourists and the hosts. The sixth item named authenticity (accounting for approximately 4.22% of variance in the data) related to experiencing an authentic culture, and avoiding typical tourist settings. The seventh item, called local natural environment, focused on appreciating nature, admiring the beautiful scenery and enjoying a healthy climate and good weather. The eighth factor, named contributing to the community, accounted for 3.16% of variance in the data.

4.3. Tourist market segmentation

As indicated in , the cluster analysis yielded a four-cluster solution. The four clusters had 40 (19.7%), 106 (52.2%), 39 (19.2%) and 18 (8.9%) cases, respectively, out of 203 observations. ANOVA tests revealed that all eight factors contributed to differentiating the four clusters (p < 0.001). The Scheffe post-hoc tests showed statistically significant differences between clusters, thereby showing that distinct clusters had been identified (see ). The clusters were subsequently labelled based on the main reasons why tourists visit villages, namely, cluster I = experiencing authenticity and learning, cluster II = experiencing different things, cluster III = relaxing with friends and relatives, visiting farms and enjoying nature, and cluster = IV passive visitors.

Table 3. Comparisons of clusters’ motivations (N = 360).

To further profile the segments, each cluster was cross-tabulated with the demographic and travel behaviour characteristics. The results of the chi-square tests showed that all clusters were found to be statistically and significantly different with respect to travel behaviour variables, such as length of stay, holiday frequency, source of information and preferable attraction, rather than the demographic characteristics ().

Table 4. Profile of the four clusters of community-based tourism in Kilimanjaro (N = 360).

4.4. Authenticity-learners

As indicates, an important reason why tourists visit rural villages is to experience an authentic cultural and to learn all they can. To attain this, they socialise with the local residents and visit their plantations. In terms of travel behaviour, indicates that tourists in this segment were mostly attracted by experiencing a different culture (65%), were mostly first-time visitors to villages (52.5%), most spent a full day or more (85%) and most obtained information about visiting villages from travel agents/tour operators and the internet (72.5%). Compared with the other segments, tourists in this segment stay longer in villages (32.5% stay more than a day).

4.5. Multi-experiences segment

As shown in , tourists in this segment comprised the majority of the respondents (52.2%), demonstrating their desire to experience a variety of things. In terms of travel behaviour characteristics, indicates that these tourists are mostly interested in cultural attractions (55.7%), stay for a half or full day in the village (88.6%) and arrange their visits mostly through tour operators. Unlike other segments, these tourists travel frequently to villages, visiting them once a year and more (43.4%). However, similar to the relaxing together segment, they obtain information about the villages from friends and relatives and the internet (76.4%).

4.6. Relaxing with friends and relatives, visiting farms and enjoying nature

This segment comprises tourists who want to relax with relatives and friends while enjoying the natural environment and visiting local farms (), and were mostly attracted by spending time in a beautiful location (51.3%). They stay in a village for a full day (66.7%), but only come every few years (43.6%). They get information about visiting villages mostly from relatives or friends (51.3%), followed by the internet (28.2%).

4.7. Passive visitors

Tourists in this segment had no particular reason for visiting villages (). Most of them (61.1%) obtained information about visiting villages from tour operators, who arranged the visits for 77.8% of them. Most of them stayed a full day and would visit cultural attractions. Although demographic factors did not significantly differentiate the segments, it is worth noting that, unlike other segments, the passive visitor segment comprises mostly older tourists (55.6% aged 50 and over).

5. Discussion

A substantial number of tourists who visit villages come from Europe to experience a traditional culture, heritage and way of life way, which shows that Tanzania depends on the European tourist market (, and URT, Citation2019), as these tourists are becoming increasingly interested in rural culture and heritage (CBI, Citation2015). This finding supports earlier results by Perkins et al. (Citation2015) and Huang (Citation2016), which suggests that the quest to experience the rural way of life and traditional heritage is becoming an increasingly popular special-interest pursuit in SSA, complementing conventional nature romanticism accompanied by relaxation and escape.

With respect to experiencing different things multi-experiences, rural tourists are mostly interested in socialising with local people, relaxing with friends and relatives, enjoying the natural environment, learning about local farming, experiencing an authentic culture and contributing to the local community (). The latter is particularly interesting, as some tourists are keen to know whether the entry fees and the money they donate contribute to social welfare and community development. This indicates the opportunity for developing volunteer tourism. Arguably, having the multi-experience segment dominating the rural tourism market means that, whilst experiencing rural cultural life is an important reason, tourists want to experience many different things. The results corroborate earlier findings in Asia and Europe that multi-experiences dominated, indicating that this trend is not limited to one particular region or continent. On the supply-side, Kilimanjaro and similar regions in Africa are indeed well-endowed with rich and diverse cultures and traditions, as well as natural attractions, which offer many different experiences. The finding that the natural environment and local culture are also important reasons means that the pull factors are as important as the push factors, which questions Li et al.’s (Citation2009) argument that the push factors are more important than the pull factors.

The authenticity-learning segment, as the second most important segment, demonstrated a great desire to experience an authentic culture, and to avoid typical tourist settings. It also showed great interest in learning about local farming methods and socialising (). The villages that were studied give tourists the opportunity to learn about people’s culture in an authentic setting, including traditional farming activities, such as livestock keeping, whereby the urine of cattle and goats is trapped differently from faeces in a special hole, and used as pesticide. Another interesting traditional farming activity is that urine and ashes are mixed and then sprayed around coffee plantations as pesticide and to neutralise the soil’s acidity. Tourists regard local organic coffee as authentic, especially its processing using traditional equipment. In villages, tourists can learn about how traditional food is cooked, which is in keeping with the natural environment. In Materuni and Marangu villages, the people use elephant grass to line the terraces in contour farming, which limits soil erosion. Zero grazing has few negative effects on the natural environment. Being keen to learn and socialise, combined with seeking authenticity and preferring cultural attractions (65%), such as a living culture, are the main reasons for staying longer in the villages ().

This result corroborates earlier findings by Park & Yoon (Citation2009) that the learning segment of the rural market values learning and socialising. This result also confirms the findings of an earlier Tanzanian investigation, which revealed that potential rural tourists were more interested in interacting with the local community (Lwoga, Citation2019). However, the non-dominance of socialising in this study can probably be explained by the fact that there were relatively few opportunities for hosts and tourists to interact. Tourists’ interactions were mostly with tour guides, local coordinators and local sellers of handcrafts.

This study found that, because tourists in the third segment enjoy relaxing with friends and relatives, visiting local farms and appreciating the attractive countryside (51.9%), this implies that they prefer classic outdoor activities such as going on nature walks, finding waterfalls where they can swim in the pools below them and visiting coffee plantations. Tours to these plantations give tourists the opportunity to experience the traditional coffee-making process, whereby they can join in the singing and dancing as the coffee beans are being pounded and ground to produce coffee grains. They can also smell and taste fresh coffee, together with local food, while traditionally-made souvenirs can be purchased. However, it was observed that visitors in this segment are less interested in socialising with the local people. Similar to the other segments, most of them (66.7%) spend at least a full day in the village, and 12.8 percent spend more than a day, thereby being the second longer-staying visitors to the villages.

This study sheds light on the passive segment that has rarely been reported in previous literature on the rural market. The passive tourists had no particular reason for visiting the villages (). Whereas Park & Yoon (Citation2009) maintained that passive tourists visited villages to enjoy the rural setting, passive tourists in this study had no intention of visiting rural villages in the first place, but were offered a village trip by tour operators. They are thus predominantly engaged in passive gazing at spectacular natural landscapes rather than searching for information and experiencing an authentic culture. This finding revealed that passive tourists’ rural visits are informal and unplanned, probably because they could not go mountaineering, and so they were offered a complementary village tour by the tour operator. It is not surprising that, compared with tourists in other segments, they depend more on tour operators to get information about the villages.

It is interesting to note that there is no significant difference in demographic characteristics between the four clusters (). This means that the motivation-based segments are more distinct in terms of their travel behaviour (except for organised tours) than their demographic characteristics. This implies that the villages have successfully attracted diverse clientele in terms of travel behaviour variables, such as length of stay, holiday frequency, information source and preferred attractions. It is observed that there was no significant difference between segments in terms of tour organisation, meaning that tourists’ visits to villages were dominantly arranged by tour operators. This implies that villages have a weak online presence, which is probably why they have been unsuccessful in creating direct sales.

6. Conclusion

Heritage tourism is complex, as its dimensions range from nature to cultural tourism, and urban to rural tourism. Past research on the heritage tourism market has focused on nature and cultural tourism in either an urban or rural context in the developed world, providing little empirical understanding of the rural tourism market in the SSA region, whose settings of heritage products differ substantially from those of the former. The objectives of this study were to explore the motivations of tourists’ visits to rural areas and to segment this market based on the push and pull factors by questioning international tourists visiting villages on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. The study provides empirical evidence that international tourists visiting rural areas are dominated by Europeans and North Americans wanting to experience authentic rural cultural life. Other motivations in order of importance are relaxing with relatives and friends, learning about local farming, socialising with local people, experiencing an authentic local culture, enjoying a local natural setting and contributing to the community. Importantly, the clustering of motivations resulted in four meaningful market segments, thereby supporting the claim that segmenting the tourism market that integrates both the push and pull factors is useful. Those seeking many different experiences, multi-experiences segment, dominate, followed by those looking for authenticity and wanting to learn, those wanting to relax with friends and relatives and visit farms, and finally those seeking to enjoy nature and casual visitors. It is thus concluded that the rural tourism market is heterogeneous and plural.

This study’s empirical examination of a Tanzanian example of rural tourism, which is dominated by tourists wanting to experience the natural heritage, has contributed to extending our understanding of the plurality of the rural tourism market in particular and of heritage tourism in general, and of the importance of cultural and many other experiences in attracting rural tourists.

The study reveals that the multi-experiences segment is the best market to focus on because, apart from tourists travelling more frequently and staying for a longer time, they socialise with local people and contribute to the community, which has the potential to enhance social welfare and economic development in the villages. In addition, the emerging Asian market should not be ignored as it is becoming an increasingly significant market for village visits.

Being able to attract four different market segments to Tanzanian villages is considered an advantage and implies that there is great potential for developing innovative products. The study recommends marketers of village tourism to consider positioning the villages to serve multiple markets. To target those in the authenticity-learning segment, they should enhance interpretation and education aids, provide rich and stimulating information, design local museums, have detailed guide books and well-trained local guides. They should also provide more opportunities for the hosts and tourists in this segment to socialise, by introducing local festivals, traditional sports and entertainment. To target relaxing with friends and relatives, visiting farms and nature lovers, coordinators could introduce interesting traditional songs and dances, and ensure the safety of natural pools. The coexistence of farming communities and the protected ecosystem should be maintained. In addition, passive visitors, who are mostly incidental, should not be ignored because they may end up having a meaningful experience (McKercher & du Cros, Citation2002). Indeed, attracting this segment does not require much investment, due to using the distinctive natural environment (Park & Yoon, Citation2009).

Tourists visiting the villages largely depend on operators arranging package tours, thereby limiting the benefits the villages would have obtained from direct sales. To capture direct sales, marketers should maintain a strong internet presence and enhance online marketing by improving village tourism websites, promoting village tourist products through online travel platforms such as Lonely Planet, online peer review sites, such as TripAdvisor, social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube, and by creating interactive village-tourist blogs. In fact, international tourists are increasingly booking their holidays directly with service providers (CBI, Citation2015).

Overall, the results of this study provide useful insights into the subject of the rural tourism market in the SSA context, but it only considered international tourists and ignored domestic ones. The study was conducted during the high season. Potentially, a longitudinal study covering both low and high seasons and the reasons why Tanzanians would choose to visit a particular location would provide a much broader picture. In addition, future studies could focus on relating people's experience of rural tourism to rural culture.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agyeiwaah, E, 2013. International tourists’ motivations for choosing homestay in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 24(3), 405–409.

- Almeida, AM, Correia, A & Pimpao, A, 2014. Segmentation by benefits sought: the case of rural tourism in Madeira. Current Issues in Tourism 17(9), 813–831.

- Anderson, W, 2015. Cultural tourism and poverty alleviation in rural Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 13(3), 208–224.

- Cawley, M & Gillmor, DA, 2008. Integrated rural tourism: Concepts and practice. Annals of Tourism Research 35(2), 316–337.

- Carvache-Franco, W, Carvache-Franco, M, Carvache-Franco, O & Hernándex-Lara, A, 2019. Segmentation of foreign tourist demand in a coastal marine destination: The case of Montanita, Ecuador. Ocean & Coastal Management 167(1), 236–244.

- CBI, 2015. Tailored intelligence study – community-based tourism (CBT) in Bolivia. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands CBO – Centre for the Promotion of Imports from developing countries.

- Cha, S, McClearly, M & Uysal, M, 1995. Travel motivations of Japanese overseas travellers: a factor-cluster segmentation approach. Journal of Travel Research 33(2), 33–39.

- Countryside Commission, 1995. Public attitudes to the countryside. Countryside Commission, Northampton.

- Eusébio, C, Carneiro, MJ, Kastenholz, E, Figueiredo, E & da Silva, DS, 2017. Who is consuming the countryside? An activity-based segmentation analysis of the domestic rural tourism market in Portugal. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 31, 197–210.

- FNSEA (Fédération Nationale des Syndicats d’Exploitants Agricoles), 1989. Les tourists français en espace rural. Analyse Qualitative. FNSLA, Paris.

- Gao, J & Wu, B, 2017. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia village, Shaanxi province, China. Tourism Management 63, 223–233.

- Goeldner, CR & Ritchie, JRB, 2006. Tourism: Principles, practices and philosophies. 10th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New Jersey.

- Hair, JF, Black, WC, Babin, BJ & Anderson, RE, 2014. Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Education Limited, London.

- Huang, WJ, Beeco, JA, Hallo, JC & Norman, WC, 2016. Bundling attractions for rural tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24(10), 1387–1402.

- Kayat, K, 2014. Community-based rural tourism: A proposed sustainability framework. SHS Web of Conferences 12, 1–7.

- Klenosky, DB, LeBlanc, CI, Vogt, CA & Schroeder, HW, 2007. Factors that attract and repel visitation to recreation sites: A framework for research. North-eastern Recreation Research Symposium, 39–45.

- Krejcie, RV & Morgan, DW, 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30, 607–610.

- Lane, B & Kastenholz, E, 2015. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches-towards a new generation concept? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 23(8-9), 1133–1156.

- Li, M, Huang, Z & Cai, LA, 2009. Benefit segmentation of visitors to a rural community-based festival. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 26 (5–6), 585–598.

- Lwoga, NB, 2019. International demand and motives for African community-based tourism. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 25(2), 408–428.

- McKercher, B & du Cros, H, 2002. Activities-based segmentation of the cultural tourism market. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 12(1), 23–46.

- Mgonja, JT, Sirima, A, Backman, KF & Backman, SJ, 2015. Cultural community-based tourism in Tanzania: Lessons learned and way forward. Development Southern Africa 32(3), 377–391.

- Nduna, LT & Van Zyl, C, 2017. A benefit segmentation analysis of tourists visiting Mpumalanga. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6(3), 1–22.

- Nyaupane, GP, White, D & Budruk, M, 2006. Motive-based tourist market segmentation: An application to Native American cultural heritage sites in Arizona, USA. Journal of Heritage Tourism 1(2), 81–99.

- Park, B, Lee, M & Kim, J, 2004. Rural tourism market segmentation. Journal of Tourism Studies 28(2), 193–212.

- Park, DB & Yoon, YS, 2009. Segmentation by motivation in rural tourism: A Korean case study. Tourism Management 30(1), 99–108.

- Perkins, HC, MacKay, M & Espiner, S, 2015. Putting pinot alongside merino in Cromwell District, central Otago, New Zealand: rural amenity and the making of the global countryside. Journal of Rural Studies 39, 85–98.

- Pesonen, J, 2012. Segmentation of rural tourists: Combining push and pull motivations. Tourism and Hospitality Management 18(1), 69–82.

- Rid, W, Ezeuduji, IO & Pröbstl-Haider, U, 2014. Segmentation by motivation for rural tourism activities in the Gambia. Tourism Management 40, 102–116.

- Rogerson, CM & van der Mwere, CD, 2016. Heritage tourism in the Global South: development Impacts of the Cradle of Humankind world heritage site, South Africa. Local Economy 31, 234–248.

- Salazar, NB, 2012. Community-based cultural tourism: Issues, threats and opportunities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(1), 9–22.

- Sidali, K & Schulz, B, 2010. Current and future trends in consumers’ preference for farm tourism in Germany. Journal Leisure/Loisir 34(2), 207–222.

- Song, DY, 2005. Why do people visit the countryside? push and pull factors. Journal of Green Tourism 12(2), 117–144.

- Tanzania Tourist Board [TTB], 2019. Tanzania cultural tourism: Authentic cultural experiences - Issue 6, Tanzania Tourist Board, Dares Salaam.

- Timothy, DJ & Nyaupane, GP, 2009. Introduction: heritage tourism and the less-developed world. In Timothy, DJ & Nyaupane, GP (Eds.). Cultural heritage and tourism in the developing world: A regional perspective. Routledge, New York, 3–19.

- Timothy, DJ & Boyd, SW, 2006. Heritage tourism in the 21st Century: Valued traditions and new perspectives. Journal of Heritage Tourism 1(1), 1–16.

- United Republic of Tanzania [URT], 2019. The 2018 tourism statistical bulletin, ministry of natural resources and tourism. Tourism Division, Dares Salaam.