ABSTRACT

The poor performance by local government institutions in service delivery has contributed to the proliferation of community-based organisations (CBOs) in many African countries. This development is unfolding within the context of growth in the aspirations of people and societies for greater transparency, democracy and participatory management. Such a scenario calls for greater social accountability by CBOs. This paper applied a realist approach guided by an action research process to assess the facilitation of community scorecards in improving social accountability by CBOs using the REPAIR project in Zimbabwe as a case study. Focus was placed on understanding the generative mechanisms within specific contexts under which social accountability outcomes emanated. The paper identified key contextual drivers, generative mechanisms and key outcomes, consolidated into streams of Context-Mechanism-Output (C–M-O) configurations. The paper concludes with recommendations on the potential utility of the C–M-O configurations for future facilitation of social accountability interventions for CBOs.

1. Introduction

The poor performance by local government institutions in service delivery has contributed to the proliferation of community-based organisations (CBOs) in many African countries. This development is unfolding within the context of growth in the aspirations of people and societies for greater transparency, democracy and participatory management. In addition, citizens are increasingly aware of available resources and more critical about their use in the interest of the public (Boelen & Woollard, Citation2011). CBOs are a sign of self-determination by marginalised communities towards community-driven efforts to enhance local development. Their sprouting has received attention and capitalised by some Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), particularly those who promote top-down development approaches that aim at community self-development. These NGOs view CBOs as having the capacity to build sustainable interventions (Middlemiss, Citation2008), through high levels of community empowerment, commitment, focus on burning community priorities, substantive community support and community ownership of their operations.

In the last two decades, the CBO-local development discourse has received considerable research attention. In this regard, a number of studies exist on the various roles that CBOs play in local level development. These inter alia include the roles of CBOs in enhancing economic development (Abegunde, Citation2009); strengthening social capital (Saxton, Citation2007); promoting community health care (Walsh et al., Citation2012); and promoting agricultural production, marketing and processing (Kindness & Gordon, Citation2001). Other studies focus on, involvement in curbing domestic violence and child abuse (Bloom et al., Citation2009), promoting educational development (Opare, Citation2007); and advancing progress in water, sanitation and hygiene (Schouten & Mathenge, Citation2010).

The rationale for the establishment of CBOs and their expected operational modalities inevitably raise the need for high levels of accountability to the communities that they serve. Such accountability will bring checks and balances on their focus on addressing the community priorities-herein later referred to as social accountability. A review of literature points out to a number of studies on social accountability of CBOs including Westhorp et al. (Citation2014), Mulgan (Citation2001), Irvine (Citation2000) and McDonald (Citation1999). These studies highlight some of the fundamental issues in accountability of CBOs to the communities they serve. Some of these issues include the focus on the value-orientation and trustworthiness of the community, which is argued to discourage internal and external accountability. In addition, CBOs face multiple accountabilities to a number of stakeholders and not a single source of authority. CBOs’ flexibility on responding to individual needs crowds out accountability in terms of general standards, such as equity (Taylor Citation1996:64).

This paper focuses on the praxis of facilitation of accountability mechanism for CBOs within rural communities using community scorecards. A community score card (CSC) is a community monitoring tool to improve accountability and responsiveness of service providers. This paper uses a case study from a United Agency for International Development (USAID) funded project implemented in four Districts in Zimbabwe (details of the project are in proceeding sections). The project aimed at improving social accountability for CBOs working in the areas of health, education, environmental management and water and sanitation. This paper does not entirely focus on how projects for improving accountability of CBOs are facilitated but rather adopts a realist evaluation approach to explore what works, under what conditions as well as the mechanisms for change and achieved outcomes. According to Pawson & Manzano-Santaella (Citation2012:177), a realist evaluation approach focuses on ‘what works for whom in what circumstances'. This approach does not only systematically track outcomes, but explicitly explains mechanisms that produce the outcomes and contexts in which the mechanisms are triggered, which are also referred to as generative mechanisms (Kazi, Citation2003:803). This paper answers the following research question: under what circumstances do community scorecards improve social accountability by community-based organisations?

2. Theoretical and conceptual grounding

2.1. Social accountability

Social accountability is defined as ‘an approach towards building accountability that relies on civic engagement, i.e. in which it is ordinary citizens and/or civil society organisations who participate directly or indirectly in exacting accountability’ (Malena et al., Citation2004:1). It is a social contract between service-providing institutions and society (Buchman et al., Citation2016:15) hence, for service delivery to be socially accountable, it must be equitably accessible to everyone and responsive to community needs. It entails a process where citizens (Rights –bearers) voice their views on service delivery to service providers (Duty-bearers) who in turn respond and account for their actions. According to Degano & Disman (Citation1997), social accountability is grounded in the concept of social justice, which presupposes each individual as having rights to civil liberties, equal opportunity, fairness and engagement in various freedoms including educational, economic, social and moral. Social accountability projects normally borrow from human rights based approaches that view the poor as central in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. In addition, amplifying citizen voices, non-discrimination, equality and inclusiveness are important principles (Ackerman, Citation2005a).

Malena et al. (Citation2004) asset that direct participation of citizens is the fundamental factor that distinguishes social accountability from other accountability mechanisms. An accountable service provider is one that pro-actively informs about and justifies its plans of action, behaviour and results and sanctioned (positively and negatively) accordingly, thus, the core elements of accountability are therefore information, justification and sanctions (Ackerman, Citation2005b). Social accountability involves a number of activities including participatory budgeting, social audits and citizen report cards. At the national level, social accountability initiatives are increasingly expected to facilitate positive development outcomes such as more responsive local government, exposing government failure and corruption, empowering marginalised groups, and ensuring that national and local governments respond to the concerns of the poor (Camargo & Jacobs, Citation2013).

Although research indicate positive outcomes from social accountability such as improved governance, increased development effectiveness through better service delivery, and empowerment (see for example Ackerman, Citation2005b), the mechanisms through which such changes are induced still need to be explored (Frankish et al. Citation2002; Thurston et al. Citation2005; O’Neil et al. Citation2007). In addition, another school of thought gives a dissimilar view that assets no direct correlation between engagement and the creation of participatory spaces (Joshi, Citation2008:15). There is an emerging discourse around understanding mechanisms through which social accountability manifests including; the Polity approach which explores conditions under which social accountability emerges and how it might work (Skocpol, Citation1992; Mahoney, Citation2000) and Realist approach that appreciates the complexity of the environment within which social accountability manifests (Lodenstein et al., Citation2013). The paper adds to this discourse through the application of a realist assessment of social accountability. The next section, therefore, gives an overview of the realist perspective to provide a theoretical context.

2.2. The realist perspective

Assessing social accountability invariably brings issues of complexity, understanding contextual issues and unfolding human agency. This study views the facilitation of social accountability within a given community as complex. The perceived complexity can be justified for the following reasons, borrowing from a typology of complexity by Pawson (Citation2013). Firstly, they are implemented in communities where there are other existing (dis)incentives and choices by the rights bearers to raise their concerns and duty bearers to listen to concerns.Footnote1 Secondly, implementation chains are often long and tortuous. Thirdly, they are implemented within contextual layers (individual, interpersonal, institutional, social, cultural economic) that are dynamic, complicated and inter-connected. Lastly, outcomes are multiple, intended and unintended.

Regarding contextual issues, on one hand, O’Meally (Citation2013) identified six contextual domains that affect social accountability intentions, these are summarised in . On the other hand, social accountability interventions can shape the context under which implementation unfolds. Context determines the social accountability strategy and its effectiveness, with some contexts being more enabling. These intricacies call for an appreciation of the complexity and context sensitive understanding of social accountability interventions. In this regard, any useful assessment of social accountability projects (for decision-making) needs to indicate ‘what works, how, in which conditions and for whom’, rather than to answer the question ‘does it work?’ This study borrowed constructs from a realist evaluation approach, a type of theory-driven evaluation that aims to ascertain why, how and under what circumstances, programmes succeed or fail within complex social system interventions. It evolved in response to a growing interest in understanding how interventions or social programmes work rather than providing success or failure assessment of their effectiveness (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997).

Table 1. Summary of the key contextual domains and sub-dimensions that influence social accountability.

The realist assessment in this study is rooted in realism and critical realism philosophy founded through the seminal works of Roy Bhaskar in the 1970s.Footnote2A key assumption of the realist assessment in this study is the existence of a ‘generative’ model of causality, where causal links are a result of events linking cause and effect to outcomes. The principle assumption lies in the generation of social accountability outcomes rather than causation by project interventions within the given context (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). This generative view on causality drives the assessment towards not looking for strict correlations between particular events but merely strives to explain how the association of these phenomena manifests.

The concept of generative mechanism focuses exactly on the question of how, in a certain context, the outcomes are generated (Holma & Kontinen, Citation2011:186). Realist assessments provide a basis to help describe how and why a complex social intervention did or did not work. It provides logic through a theory-driven inquiry that explains what works, for whom, in what circumstances and in what respects (Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2012). The programme theory outlines the pathways for change and is moulded around a context-mechanism-outcome configuration [Context + Mechanism=Outcome (C+M=O)]. Realistic assessments offer deep insights into the links between programme and outcomes by exploring interactions between programme, actors, context and mechanisms. This implies that, within any programme theory for a complex intervention, there are multiple CMOCs. Programmes or interventions, therefore, attempt to change the contexts through triggering appropriate mechanisms to give the desired outcomes (Wong, Citation2018:110).

3. The rationale of the REPAIR project and the theory of change (TOC)

3.1. Project rationale

The Resilience through Peaceful and Inclusive Relationships (REPAIR) project aimed at increasing community resilience to violence in polarised communities by restoring relationships and strengthening CBOs’ responsiveness to community needs through improving social accountability. The project worked with Community Resource Management Committees (CRMCs)Footnote3 which are CBOs responsible for collective management of local resources. The project was implemented between June 2016 and December 2017. It focused on improving decision-making on resource management, fostering constructive engagement across the selected communities, and support meaningful interaction with local governing authorities. CRMCs in the health (Health Centre Committees-HCCs), education (School Development Committees -SDCs), environment (Environmental Management Committees -EMCs), and water & sanitation sectors (Water Point Committees -WPCs) were targeted to serve as constructive, inclusive decision-making spaces for effective resource management, relationship strengthening and strengthening responsiveness and accountable by CRMCs to community concerns. The project was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), jointly implemented by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and the International Institute for Development Facilitation (IIDF) Trust.

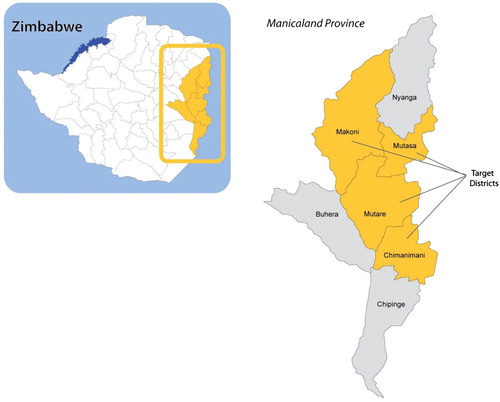

The project was implemented in four districts of Manicaland Province in Zimbabwe; Makoni, Mutare, Chimanimani, and Mutasa (see ) – reaching approximately 4,000 direct and 130,000 indirect beneficiaries. According to the last census (ZIMSTAT, Citation2012), the total population figures for the four districts were: Makoni (72,340), Mutare rural (262,124), Chimanimani (143,940) and Mutasa (168,747). According to ZIMSTAT (Citation2017), Manicaland Province has the highest proportion of households living in poverty (16.5%) in Zimbabwe, with a percentage poverty prevalence of 71%. The province has a considerable number of CBOs working on diverse issues including public health, youth empowerment, community-based advocacy and socio-economic development.

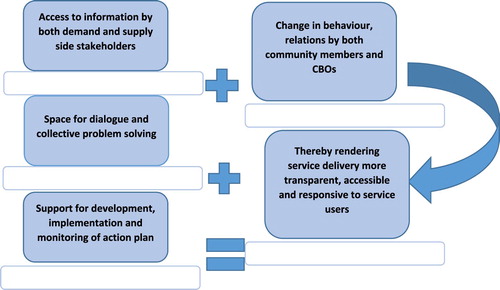

The project premised on the underperformance of CRMCs and their inability to act as spaces for constructive interaction and collective problem solving. Exclusion of certain groups (particularly along political and gender lines) from decision making on public resources such as water, health and education services, worsened grievances among marginalised groups. The use of Community Score Cards (CSCs) allowed the development of self and peer assessment mechanisms and NRMCs acquired space to develop inclusion/transparency strategies and implement steps to respond to community interests. The Community Score Card (CSC) is a two-way and continuous participatory tool for assessment, planning, monitoring and evaluation of services. It brings together the demand side (service user) and the supply side (service provider) of a particular service or programme to jointly analyse issues underlying service delivery problems and find a common and shared way of addressing those issues (Care Malawi, Citation2013). The CSC process for the REPAIR project had four components: dissemination of information to service users about their rights; development of performance scorecards by users and self-assessment scorecards by service providers; space for dialogue and joint problem solving by users and providers; and development, implementation, and monitoring of a shared action plan.

The CSC process was preceded by a Rapid Functionality Assessment (RFA) to acquire valid information on current status of CBOs that provided benchmarks for measuring project success or failure, with 56 CBO members participating in the assessment. A total of 2050 community members from the four Districts (934 males and 1116 females) participated in the CSC process. Input Tracking Matrices (ITM) were developed with community members in March 2017, to collect objective information on service performance in targeted sectors using the national norms on users’ entitlements. This was followed by the development of Community Generated Performance Score Cards (CGPSCs) to gather inputs from community members and CBOs on potential solutions to redressing service delivery challenges. This allowed generation of success indicators and a commonly agree scoring process. The process of developing Service Provider Self-Evaluation Score Cards was facilitated in April 2017 across all four implementing districts. The process involved performance measurement of services by CBO members without the involvement of community members. This culminated into the final stage, leading to the development of Joint Service Improvement Plans (JSIPs) through interface meetings between CBOs and community members. The CSC process was reviewed through community review meeting. Twenty (20) community review meetings were conducted in September 2017.

3.2. Theory of change (ToC)

Realist assessments start with unpacking the theory of change with the results of the assessment aiming towards contributing to strengthening the ToC. The REPAIR project was premised on two mutually reinforcing assumptions that addressed both the demand and supply sides of service delivery by CBOs. The first focused on relationship building at the community level (demand side) through improved resource management: IRC outlined the assumption as follows:

If community members from across the political divide are able to engage constructively with each other to address resource management concerns in inclusive, non-partisan spaces, then they will be able to counter feelings of exclusion, establish common ground, strengthen relationships, and address grievances, thereby increasing resilience and decreasing the likelihood of violence (IRC, Citation2016).

If local institutions increase their capacity to perform impartially and engage constructively with communities and other local actors, then they will be able to respond more effectively to community concerns and improve accountability, thereby presenting a viable option to address grievances and decreasing the likelihood of violence (IRC, Citation2016).

Table 2. Expected outcomes from the REPAIR project.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Conceptual framework

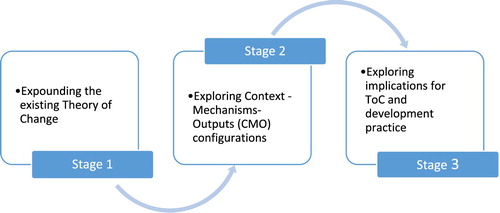

This study was conceptualised in three stages. The first stage involved explicit outlining of the REPAIR theory of change. The second stage focused on exploring the Context-Mechanisms-Outcomes (C–M-O) configuration. This stage involved the identification of the features of context that affect how the interventions worked and articulation of the outcomes from the REPAIR project. These were consolidated into streams of C–M-O configurations (see ). The final stage focused on exploring implications on the theory of change and implications for future programming. The conceptual framework is outlined in .

4.2. Data collection

This study utilised a qualitative research design through an action research process. The author was engaged in action research between the periods June 2016 to December 2017 as a Project Advisor and was actively involved in field work. Throughout the research process, the author was taken as an ‘insider’ due to previous engagements in the districts through other projects. This helped in creating trust and rapport with the CBOs and community members. The community mobilisation process was conducted in partnership with local authorities (Rural District Councils) at district level and Ward Development Committees (WADCOs) together with Village Development Committees (VIDCOs) at the local level. Traditional leaders and ward councillors were placed at the fore front of community mobilisation activities to enhance project ownership and allow the project to be smoothly integrated into existing local development activities. The action research process involved cycles of planning-action-reflection at the community and implementing partner levels. During the action research cycles, qualitative data were collected using fieldwork diaries, review of project monthly and quarterly progress reports, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), Community Identified Significant Change Stories (CISCSs), Key Informant Interviews (KIIs), quarterly review meetings and after action reflection meetings. . Shows the main action research streams conducted during the research period.

Table 3. Key action research sessions.

4.3. Data analysis

The context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configuration, as the main conceptual tool, guided the data analysis process. The analysis of qualitative data from interviews, transcripts and documents were based on coding in terms of ‘description of the actual intervention’, ‘observed outcomes’, ‘context conditions’ and ‘underlying mechanisms’. The results were compiled into a C–M-O table (See ). Verifications of the emerging CMO configurations were conducted with other Facilitators from the action research process (including project managers, field officers and monitoring and evaluation officers from both IIDF and IRC) as a form of triangulation.

Table 4. The consolidated Context-Mechanism-Outcome configurations.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Overview of the broad context

The action research process was conducted in a politically polarised environment. Differences in partisan politics in the four Districts led to exclusion of some community members in decision-making and allocation of public resources by CBOs along political affiliations. In addition, relationships were damaged by years of violence, repression, poor and biased service delivery, preventing community members from working together to seek redress for their shared grievances. Partisan decision-making by CBOs and gaps in capacity severely compromised resource management and service delivery at the local level, augmenting grievances. Rather than being accountable to their communities, CBOs became accountable to political institutions. In addition, results of a gender analysis study conducted by USAID funded ENSURE program (Citation2014) in the four districts showed that more than 90% of key decision-making positions were male dominated thus depressing women's voices and aspirations. Baseline surveys at the inception of the REPAIR project showed limited knowledge by the community and CBOs on national norms on users’ entitlements regarding services from the health, environmental management, water & sanitation and education sectors. CBOs were not aware of government standards governing service delivery for public resources from the four sectors.

5.2. Contextual factors that drove social accountability

The study identified a number of contextual factors that influenced generative mechanisms for social accountability of CBOs. These contextual factors are as follows:

Enhancing community ownership and buy in of the process- Experience in rural development projects by a number of NGOs in Zimbabwe have shown that most rural communities do not appreciate ‘soft’ projects i.e. projects that focus on non-tangibles such as capacity building, skills development, etc., instead they prefer projects that bring tangibles such as food aid and infrastructure development. Community mobilisation by IIDF and IRC coupled with a transformative approach that highlighted the benefits of social accountability by CBOs contributed to changes in mind-sets.

Maintaining political neutrality— the environments at the onset of the project were politically polarised, with power tensions and strained relationships between traditional and elected leadershipFootnote4 and among community members from different political parties. In addition, local government officials were apprehensive in working with elected leaders from the opposition political parties due to fear of political victimisation. Maintaining a neutral political stance allowed effective implementation of the project.

Reducing reticence and improving participation of marginalised groups- The majority of the population of Manicaland province in Zimbabwe consists of the Manyika ethnic group. They are generally a conservative society in which women and youths do not participate freely in public engagement processes. Deliberate mobilisation of the marginalised and creation of inclusive dialogic spaces through participatory processes paved the way for community wide participation in the project.

Enhancing knowledge of entitlements – At the inception of the project, both the demand and supply sides had limited knowledge on entitlements to various services. Improving social accountability by CBOs required an environment where community members knew their rights to entitlements by service providers and where service providers did not view social accountability as witch hunting and policing, but rather a mutually beneficial arrangement.

Appreciating local leadership dynamics - The four districts had wards with diverse leadership dynamics. This is highlighted by the following quotation from IIDF reports that highlight the uniqueness of a selected ward:

‘ … ward (27) leadership whose uniqueness lies in the absence of traditional leaders in the development structure has a Committee of Seven comprising mostly liberation war veterans who are hostile and will not allow the CSC ward facilitators to implementing the process unless they are introduced to the community by the opposition ward councillor whom they avoid working with … ’(IIDF, Citation2017).

Situational and differential engagement of local leadership allowed effective engagement of varying local leadership structures.

Competing NGO approaches - The project was implemented in an environment engulfed by numerous NGOs with competing approaches. This brought complications with regards to engaging community members. Competing demands for the same community brought some rent seeking behaviour by some sections of the community, examples are captured in the following quotations:

‘ … Community members requested for either lunches or refreshments during the implementation of the Community Score Card … ’

‘ … in Ward 4, traditional leaders demanded that IIDF/ IRC pay them a token amount of money before working together on the Water Points and Environment sectors … ’ (March 2017) …

Building faith in the process- community scepticism on the sustainability of development interventions marred the implementation process of the REPAIR project. The communities had prior experiences with some NGO funded projects that had failed in the past. IIDF and IRC continuously emphasised the perceived benefits of the REPAIR project as a way of building confidence and faith in the project.

5.3. Generative mechanisms (GMs)

The research process identified three categories of generative mechanisms that drove social accountability by CBOs. These are detailed in the proceeding section and utilised in developing streams of context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations summarised in .

5.3.1. The sanctions pathway

GM1 –IF CBOs face the loss of resources, social status, employment, votes, or other forms of support for not taking people's perspectives into account, THEN they will take people's articulated demands more seriously.

GM2 –IF people can organise collectively to identify ways in which CBOs face credible sanctions, THEN they can articulate their demands in ways that leverage this threat of sanctions.

GM3–IF CBOs face credible sanctions for not taking people's perspectives into account and IF vested interests have reduced influence on them and IF they have access to accurate information on people's perspectives and IF they have the organisational capabilities to process and respond to this information, THEN people can influence key decisions that affect their lives collectively.

GM4 –IF the local community leadership (both traditional and elected leadership) play a ‘Big brother is watching’ approach, THEN CBOs will respond in anticipation of the application of rewards and sanctions.

GM5 –IF, the local community leadership (both traditional and elected leadership) plays ‘Elder/Council authority’ THEN strengthened relationships between CBOs and local leadership lend credibility and authority to the CBOs to take specific actions to improve service delivery.

5.3.2. The shared-interests and collective-efficacy pathway

GM6 –IF people can organise collectively to identify areas of common interest with CBOs, THEN they can articulate their demands in terms of these shared interests.

GM7 –IF CBOs recognise their shared interest with peoples’ articulated demands and if they have the organisational capabilities to process and respond to this information, THEN people can influence key decisions that affect their lives collectively.

GM8–IF Mutual accountability is developed, in which all parties commit to an agreed action plan to monitor the performance of each other, THEN there is trust and commitment to meet agree on deliverables from both the people and the CBOs.

5.3.3. The community-awakening pathway

GM9 –IF people are conscious about the gap in service delivery in which discrepancies between rights or entitlements and actual provision surprise or concern them, THEN they will demand appropriate services and will not agree to less.

GM10 –IF people realise that service provision is the key to the future of their livelihoods, THEN there is increased understanding of and support for CBOs through individual or collective action to support CBOs.

GM11–IF people realise positive outcomes from any action (It's working!) THEN seeing operates as a positive feedback loop motivating further action

GM12 –IF the people take the role of ‘eyes and ears’ in which they act as local-data collectors for monitoring purposes and forwarding information to another party which has the authority to act (local and District authorities in the case of the REPAIR project), and if the people are aware of the consequences of the party not acting, THEN the party that receives the information has an obligation to act.

5.4. The context-mechanism-outcome configurations

presents the streams of Context-Mechanism-Outcome configurations that triggered outcomes for improving social accountability of CBOs through the REPAIR project. It outlines a consolidated picture of perceived generative mechanisms for specific outcomes and the contextual factors within which the outcomes emerged. As outlined in section 2.2, it should be recognised that enhancing social accountability is a complex process hence, in reality, the C–M-O mechanisms are not as linear and simplistic as illustrated in . They involve complex interactions amongst various contextual drivers, GMs and outcomes.

5.5. Discussion on the outcomes

The REPAIR project produced a number of outcomes, which were in line with expected outcomes from the Theory of change (see ). There was evidence of improvement in Inclusive decision making through the development of Joint Service Improvement Plans (JSIPs).Footnote5 This process was reported to have provided an opportunity for the CBOs and service users to remove suspicion through a transparent process that facilitated inclusive decision making for the improvement of service provision. There was evidence of commitment to improved service delivery from the supply side. Interface Meetings raised the awareness of national standards guiding the provision of basic services in the targeted sectors. The scorecard process revitalised zeal in the CRMCs whose level of commitment to service delivery and accountability was enhanced through the acquisition of knowledge and understanding of roles and responsibilities. Despite these outcomes, it was evident that initially the community score card process was viewed with mixed feelings as outlined in the following quotation by a service provider from the education sector:

… Teachers viewed the process as a witch hunt especially after Input Tracking Matrix stage which they referred to as data collection meant for exposing inadequacies in schools. They referred the process as an official secret activity whose main purpose was to expose schools of their ill-practises … (IIDF, Citation2017)

The results indicated that the project enhanced a deeper appreciation of the level of deterioration in service delivery. Exposure to entitlements for the community increased awareness on the standards of service delivery expected from the CBOs, coupled with an appreciation by the CBOs of the level of inefficiencies in service delivery. There was improved relationships, trust and communication between service users and service providers. The process of joint decision- making, consensus building, joint planning built trust between service users and service providers. Relationships among community members (both within CRMCs and in the wider community) were restored. For example, service users became open and exposed issues that deterred commitment to engage in efforts for improving service delivery. The quotation below highlights some of the issues that deterred parents from engaging in improving services in the education sector:

… Parents were not attending general and consultation meetings and cited reasons such as fear of intimidation since they were not paying school fees and unwillingness to exert themselves to mould bricks required for classroom construction. Such schools include Gurure and Mukamba primary schools in Makoni district … (IIDF, Citation2017)

There was an improved community understanding of rights and responsibilities. At the inception, service users showed limited awareness of their rights. However, the introduction of the CSC increased demands from users claiming their rights and pushing service providers to meet their responsibilities. There was evidence of improved appreciation of service provider constraints. Before the CSC process, the community blamed the service providers for deteriorating service delivery in the four facilities without considering the constraints and limitations they faced. The Inputs Tracking Matrices provided an opportunity for the service providers, CRMCs and service users to reduce suspicion through a transparent process that facilitated inclusive decision making for the improvement of the facility.

Evidence of Community empowerment was reported. The process of raising issues, generating indicators and prioritisation has empowered communities and built their confidence to give constructive feedback, raise issues and request improvements to services. There is a progressive increase in community participation in decision-making processes and the associated sense of ownership. The process has been viewed as empowering the previously marginalised women and youths who participated fully in the crucial stages of the community generated performance score card and the interface meetings. A majority (54%) of the people who participated in the CSC process were women who dominated the water and health sectors

6. Conclusion and implications for development practice

This paper applied a realist approach to the assessment of facilitation of community scorecards in improving social accountability by CBOs using the REPAIR project in Zimbabwe as a case study. The focus was on understanding the generative mechanisms within specific contexts under which research outcomes emanated. Conceptually, the research followed a three stage process involving expounding the REPAIR theory of change, exploring Context-Mechanisms-Outputs (C–M-O) configurations and exploring implications for future programming. The study identified key contextual drivers for social accountability to include: enhancing community ownership and buy in; maintaining political neutrality; reducing reticence and improving participation by marginalised groups; enhancing knowledge of entitlements; appreciating local leadership dynamics; and building faith in the process. Three sets of generative mechanisms were identified; sanctions pathway shared interests and collective pathway, and community awakening pathway. Key outcomes from the community score card process included: inclusive decision making; commitment to improved service delivery by CBOs; appreciation of the level of deterioration in service delivery; improved relationships, trust and communication; improved understanding of rights and responsibilities; and community empowerment. It should be appreciated that the C–M-O configurations identified in the study are not linear in reality. They form a web of interrelationships and interconnectedness, thus they provide a simplistic and indicative picture of the mechanisms behind outcomes with the context of the REPAIR project.

The research findings have a number of implications on the REPAIR theory of change and practice recommendations with regards to the use of C–M-O configurations in practice. In practice, the C–M-O configurations would have been important in informing formative evaluations for the REPAIR project. However, this study being an ex-post assessment has more relevance in informing future practice. The C–M-O configurations identified in this study are useful in planning future projects within similar contexts though addressing issues around how proposed interventions are expected to work and identification of potential barriers and mitigation measures to ensure success. In conclusion, it should be realised that C–M-O configurations are inextricably linked and may be useful in practice to provide a starting point for thinking about particular interventions, the ways in which they work (or fail to work), the factors that affect whether and how they work, and the outcomes that they generate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See (Lodenstein et al., Citation2013) for detailed examples.

2 This paper will not dwell into the philosophical foundations of Realism. For detailed accounts see for example Pawson (Citation2013), Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997) and Bhaskar (Citation1978).

3 In this paper the terms CRMCs and CBOs will used interchangeably.

4 Chiefs on one hand claim that they are the legitimate representatives of the people as they are permanent and sanctioned by a higher authority (the ancestors), whilst on the other hand councilors claim that they have a mandate from the people because they were directly elected.

5 These were jointly developed by the community and CBOs to provide modalities for improved service provision.

References

- Abegunde, AA, 2009. The role of community based organisations in economic development in Nigeria: The case of Oshogbo, Osun state, Nigeria. International NGO Journal 4(5), 236–252.

- Ackerman, JM, 2005a. Human rights and social accountability. Social Development Papers. Participation and engagement. Paper No. 86. The World Bank.

- Ackerman, JM, 2005b. Social accountability for the public sector: A conceptual discussion. The World Bank, Social Development, Paper No. 82, Washington.

- Bhaskar, R, 1978. A realist theory of science. Harvester Press, Brighton.

- Bloom, T, Wagman, J, Hernandez, R, Yragui, N, Hernandez-Valdovinos, N, Dahstrom, M & Glass, N, 2009. Partnering with community-based organizations to reduce intimate partner violence. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 31(2), 244–257. doi: 10.1177/0739986309333291

- Boelen, C & Woollard, R, 2011. Social accountability: The extra leap to excellence for educational institutions. Medical Teacher 33(8), 614–619. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.590248

- Buchman, S, Woollard, R, Meili, R & Goel, R, 2016. Practising social accountability: From theory to action. Canadian Family Physician 62, 15–18.

- Camargo, CB & Jacobs, E, 2013. Social accountability and its conceptual challenges: An analytical framework. Working paper series No. 16. Basel Institute on Governance, Basel.

- CARE Malawi, 2013. The community score card (CSC): A generic guide for implementing CARE’s CSC process to improve quality of services. Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc., Lilongwe.

- Degano, R & Disman, M, 1997. Cultural competency handbook. Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

- Dutschke, M, 2014. The community score card evaluation report 2014. Blacksash making human rights real. Johannesburg.

- ENSURE, 2014. Gender analysis draft report. SNV, World Vision, CARE and SAFIRE. Enhancing Nutrition, Stepping Up Resiliency and Enterprises Project. Harare.

- Frankish, CJ, Kwan, B, Ratner, PA, Wharf Higgins, J & Larsen, C, 2002. Challenges of citizen participation in regional health authorities. Social Science & Medicine 54(10), 1471–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00135-6

- Holma, K & Kontinen, T, 2011. Realistic evaluation as an avenue to learning for development NGOs. Evaluation 17(2), 181–192. doi: 10.1177/1356389011401613

- International Institute for Development Facilitation Trust (IIDF), 2017. REPAIR Final Narrative Report. Harare, mimeo.

- International Rescue Committee (IRC), 2016. Resilience through Peaceful and Inclusive Relationships (REPAIR) Concept Document. Unpublished Mimeo.

- Irvine, H, 2000. Powerful friends: the institutionalization of corporate accounting practices in an Australian religious /charitable organisation. Third Sector Review 6(1,2), 5–26.

- Joshi, A, 2008. Producing social accountability? The impact of service delivery reforms. IDS Bulletin 38(6), 10–17. Institute of Development Studies. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2007.tb00414.x

- Kazi, M, 2003. Realist evaluation for practice. British Journal of Social Work 33, 803–818. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/33.6.803

- Kindness, H & Gordon, A, 2001. Agricultural marketing in developing countries: The role of NGOS and CBO. Policy Series 13. Natural Resources Institute University of Greenwich.

- Lodenstein, E, Dieleman, M, Gerretsen, B & Broese, JEW, 2013. A realist synthesis of the effect of social accountability interventions on health service providers' and policymakers' responsiveness. Systematic Reviews 2, 98. 10 pages. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-98

- Malena, C, Forster, R & Singh, J, 2004. Social accountability: An introduction to the concept and emerging practice. The World Bank, Social Development Papers No 76, Washington.

- Mahoney, J, 2000. Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and Society 29(4), 507–48. doi: 10.1023/A:1007113830879

- McDonald, C, 1999. Internal control and accountability in non-profit human organisations. Australian Journal of Public Administration 58(1), 11–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-8500.00065

- Middlemiss, L, 2008. Influencing individual sustainability: A review of the evidence on the role of community-based organisations. International Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development 7(1), 78–93. doi: 10.1504/IJESD.2008.017898

- Mulgan, R, 2001. The accountability of community sector agencies: A comparative framework. Discussion Paper No.85.

- O’Meally, SC, 2013. Mapping context for social accountability: A resource paper. Social Development Department, the World Bank, Washington DC.

- O’Neil, T, Foresti, M & Hudson, A, 2007. Evaluation of citizens’ voice and accountability: Review of the literature and donor approaches. DFID.

- Opare, S, 2007. Strengthening community-based organizations for the challenges of rural development. Community Development Journal 42(2), 251–264. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsl002

- Pawson, R, 2013. The science of evaluation: a realist manifesto. SAGE, London.

- Pawson, R & Manzano-Santaella, A, 2012. A realist diagnostic workshop. Evaluation 18(2), 176–191. doi: 10.1177/1356389012440912

- Pawson, R & Tilley, N, 1997. Realistic evaluation. SAGE, London.

- Rycroft-Malone, J, McCormack, B, Hutchinson, AM, DeCorby, K, Bucknall, TK, Kent, B, Schultz, A, Snelgrove-Clarke, E, Stetler, CB, Titler, M, Wallin, l & Wilson, V, 2012. Realist sythesis: Illustrating the method for implementation research. Implementation Science 7, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-1

- Saxton, GD, 2007. Social Capital and the Vitality of Community-Based Organizations. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Western Academy of Management, Missoula, MT, March 21–24, 2007.

- Schouten, MAC & Mathenge, RW, 2010. Communal sanitation alternatives for slums: A case study of Kibera, Kenya. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 35(13), 815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.pce.2010.07.002

- Skocpol, T, 1992. Protecting soldiers and mothers. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Taylor, M, 1996. Between public and private: Accountability in voluntary organisations. Policy and Politics 24, 57–72. doi: 10.1332/030557396782200418

- Thurston, WE, MacKean, G, Vollman, A, Casebeer, A, Weber, M, Maloff, B & Bader, J, 2005. Public participation in regional health policy: A theoretical framework. Health Policy 73(3), 237–252. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.11.013

- Walsh, A, Mulambia, C, Brugha, R & Hanefeld, J, 2012. The problem is ours, it is not CRAIDS’. Evaluating sustainability of community based organisations for HIV/AIDS in a rural district in Zambia. Globalization and Health 2012(8), 40. 16 pages. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-40

- Westhorp, G, Walker, DW, Rogers, P, Overbeeke, N, Ball, D & Brice, G, 2014. Enhancing community accountability, empowerment and education outcomes in low and middle-income countries: A realist review. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

- Wong, G, 2018. Getting to grips with context and complexity − the case for realist approaches. Gaceta Sanitaria 32(2), 109–110. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.05.010

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT), 2012. Census 2012: Preliminary Report. Causeway, Harare.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT), 2017. Zimbabwe Poverty Report 2017. Causeway, Harare.