ABSTRACT

Inclusive tourism is a major focus in international scholarship. The South African record is significant as national government addresses the apartheid legacy of the historical exclusion of black communities from participation in the mainstream economy. The objective is to examine the potential of leveraging state assets for achieving a more inclusive tourism economy. The specific focus is the use of municipal assets with evidence from the Overstrand local municipality which centres upon the tourist town of Hermanus, Western Cape. This municipality has a significant basket of municipal assets which can be leveraged for tourism development, including for the potential benefit of entrepreneurs from disadvantaged communities. The results reveal that several of these assets are underperforming for the local tourism economy. The nexus of municipal asset management and inclusive tourism merits further scholarship.

1. Introduction

Among others Kadi et al. (Citation2019:1) observe that how widely the benefits of tourism ‘are shared has long been a key scholarly, social and political concern’. One specific issue coming under closer academic and policy scrutiny is the ‘inclusiveness’ of tourism development. Saito et al. (Citation2018:175) maintain that whilst the economic impacts of tourism are considerable across several parts of the global South ‘those most in need often benefit very little from the tourism sector’. Heightened academic and policy debate around the nexus of tourism and economic inclusion is the consequence of ‘inclusion’ being incorporated as one of the core principles of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals which were ratified in 2015 (Scheyvens & Hughes, Citation2019). The mounting calls for inclusion derive from the fact that certain groups or communities often are ‘left out’ of tourism development processes on the grounds either of their gender, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation or poverty (Scheyvens, Citation2011).

For Scheyvens & Biddulph (Citation2018:589–90) the tourism sector stands

accused of providing opportunities for the privileged middle and upper classes to travel and enjoy leisure activities in ‘other’ places, creating profits particularly for large companies and creating enclaves for the rich, while development opportunities associated with tourism are not open to those who are poor and marginalized.

This concept of inclusive tourism is put forward both as an analytical concept and aspirational ideal (Kadi et al., Citation2019). For its proponents the discussion around inclusive tourism ‘is a direct attempt to acknowledge that many people have been excluded by tourism in the past, and to find ways to overcome this so that more people can benefit from tourism’ (Scheyvens & Biddulph, Citation2018:593). Indeed, potentially it ‘can be used to evaluate current tourism practices to help to detect where changes are needed, as well as to guide new tourism development’ (Biddulph & Scheyvens, Citation2018:587). A recent burst of international scholarship emerges around the concept of inclusive tourism and the inclusiveness of tourism development processes (Bakker & Messerli, Citation2017; Bakker, Citation2019; Rogerson, Citation2020a). Such debates represent an extension and refinement of those which have taken place over the previous 15 years around tourism’s role in poverty reduction and the innovation of ‘pro-poor tourism’ approaches (Rogerson & Saarinen, Citation2018).

Overall it is conceded ‘tourism development’ can be inclusive and assist towards poverty reduction only if a broad array of stakeholders contribute both to the creation of opportunities as well as sharing potential benefits. One key research issue is, therefore, to identify the drivers or constraints for the achievement of inclusive tourism (Bakker, Citation2019). Within the growing international scholarship on inclusive tourism the South African experience is of compelling interest because of national government’s desire to address the apartheid legacy of the historical exclusion of black communities from participation in the mainstream economy (Butler & Rogerson, Citation2016; Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2019a). Indeed, whilst South Africa has come a long way since the advent of democracy, the findings of a recent World Bank (Citation2018:iii) investigation are that the economic transition ‘from a system of exclusion under segregation and apartheid remains incomplete’. Progress towards a more sustainable and inclusive tourism development pathway would be one element of overcoming the legacy of exclusion in South Africa (World Bank, Citation2018). The revised national tourism strategy of South Africa (issued in 2018) demands broadening the economic beneficiaries of tourism development and stresses the imperative for attracting and supporting more black entrepreneurs as owners and operators of tourism small medium or micro-enterprises (SMMEs) (Department of Tourism, Citation2018a).

Against this backdrop this paper’s objective is to examine the potential of leveraging state assets for achieving a more inclusive tourism economy. Arguably, the mobilisation of local assets for energising local development is a policy challenge for sub-national levels of government. Local governments hold or control significant baskets of physical assets such as land, buildings and infrastructure which can be valuable for promoting local economic well-being (Kaganova, Citation2010; Kaganova & Kopanyi, Citation2014). The maximisation of local assets specifically for tourism development represents a form of government involvement that would be categorised as ‘developmental active involvement’ in tourism (Jenkins & Henry, Citation1982). The research focus is upon the use of municipal assets with evidence from a case study of Overstrand local municipality centred upon the tourist town of Hermanus, Western Cape. Three sections of material are given. First, the growth of South African government policy interest in leveraging state assets for support of black SMME involvement in tourism is reviewed. Second, a brief discussion of the study locality, the historical development of tourism, and the contemporary character of Overstrand tourism is presented. Third, an analysis is undertaken of the chequered record of using municipal assets to leverage greater inclusion in the local tourism economy.

The discussion draws from a range of primary documentary sources which include archival sources from the national library (Cape Town), recent and contemporary planning documents of the municipality, the local tourism data information from IHS Global Insight and, most importantly a group of semi-structured interviews which were conducted during 2018 with key tourism stakeholders in Hermanus. The stakeholder interviews included the former CEO of the Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, the head of the local heritage association, the marketing director for the Cape Whale Coast Association, heads of tourism marketing for Gansbaai and Stanford, three local property developers, staff and personnel (including community members) working at the municipal assets (especially the museums) and several key private sector tourism stakeholders including the leader of a local think-tank set up to improve the tourism economy. The paper contributes to international scholarship around inclusive tourism and to expand local debates around demand-side interventions to support black entrepreneurial involvement in South Africa’s tourism economy (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2019a; Giddy et al., Citation2020).

2. Changing support policy for black SMME involvement in South African tourism

Over the past two decades South Africa has introduced a range of support programmes and initiatives targeted to expand the participation of black entrepreneurs in the country’s tourism economy, specifically for SMME development to support wider objectives of transformation and inclusive tourism (Rogerson, Citation2005, Citation2007; Department of Tourism, Citation2018c). Transformation legislation was introduced in order to address the debilitating legacy of apartheid policies which included the deliberate marginalisation if not outright exclusion of black business development within the former space of ‘white’ South Africa (Abrahams, Citation2019). The policy interventions since 2000 have been geared to tackle the particular challenges and needs of SMMEs in the tourism sector (Department of Tourism, Citation2016; Bukula, Citation2018).

Under the Department of Tourism’s Enterprise Development Programme are several focal areas including market access, supplier development, mentorship and coaching, training and development, an information portal, and incubation. Recent interventions include assistance for tourism business incubators (Rogerson, Citation2017). In alignment with other national government programmes for inclusion the support provided by the Department of Tourism is to create a conduit for economic inclusion by building the competitiveness of tourism businesses for increased sustainable jobs, economic growth and development. Further impetus for black SMME development derives from the implementation of BBBEE Codes and especially of Enterprise and Supplier Development which is viewed as a key driver for transformation (Department of Tourism, Citation2018b).

Additional support for tourism SMME development emerges from cooperation between the departments of tourism and small business development (DSBD). The mandate of the DSBD – the core national government department with responsibility for SMME development since its establishment in 2014 – is ‘the coordination of efforts towards a strong and sustainable community of SMMEs and Cooperatives to enable them to contribute positively to economic growth and job creation in South Africa’ (Department of Small Business Development, Citation2018:4). The DSBD initiated a National Interdepartmental Coordinating Committee to establish a government-wide perspective as well as promote the development of SMMEs through inter-departmental planning. This committee is made up of representatives of 24 government departments including tourism. Among key DSBD interventions are to improve access to financial and non-financial support, build market access for SMMEs, support the national township and rural enterprises strategy, and drive a policy, legislative and regulatory review for ‘red tape’ reduction. The DSBD’s National Red Tape Reduction Strategy is to counter the negative impacts of red tape on small businesses as a whole. Among its objectives is the removal of barriers hindering new tourism ventures and most importantly ‘including a typical bureaucratic mind-set of “it’s against the rules or not in the rules’ need to be addressed”’ (Department of Tourism, Citation2018c:8). DSBD seeks also to strengthen government procurement programmes for supporting SMME development as a whole, and by implication also to include the tourism sector.

The full impact and ramifications of this group of recent policy measures for tourism SMME development remains to be evaluated. One 2018 report concerning the state of transformation in the South African tourism sector suggests the pace of change is ‘slow’ and ‘concerning’ (Department of Tourism, Citation2018b:71). Arguably, public sector support for SMMEs typically has assumed the form of mainly supply side interventions in which a range of services are delivered to enterprises. Bukula (Citation2018:89) maintains that while such interventions can and do provide beneficial support ‘many are questionable when it comes to the scale and sustainability of benefits derived by participants’. What is evident is the rising national government interest to complement supply side support interventions with demand-side initiatives such as leveraging the potential of state-owned assets in South Africa for tourism development and particularly for upgrading the role of black entrepreneurs. State assets include those of national and provincial government as well as municipal assets. The most significant state assets are those game parks and major nature reserves falling under the control of SANParks, North West Parks and Cape Nature. A range of municipal assets also exist which encompass small nature reserves, accommodation complexes, camp sites, caravan parks and even lighthouses (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2019a).

Tourism is a strategic focus for local economic development (LED) across South Africa (Nel & Rogerson, Citation2016). The maximisation of municipal assets can assume a vital role in galvanising tourism-led LED as well as boosting inclusion particularly in small towns (Rogerson, Citation2020b). The Department of Public Works (Citation2008) has driven the preparation of a government-wide immovable asset management policy one of the objectives of which is to enhance and optimally support government socio-economic objectives. The need for such a policy framework derives from the fact that historically ‘immovable asset management practices in government resulted in immovable assets slipping into disrepair due to improper funding and maintenance’ (Department of Public Works, Citation2005:2). In addition, within the context of the massive service delivery and other challenges confronting local governments across South Africa ‘immovable asset management is a low priority’ (Department of Public Works, Citation2005:2). Many less well-resourced local municipalities confront difficulties in appropriately managing their municipal assets for tourism. Evidence from East London is that ‘many South African municipalities are failing to incorporate their assets effectively’ for tourism development (Dlomo & Tseane-Gumbi, Citation2017:3). Critical findings relate not only to poor maintenance of municipal assets that could be utilised for tourism development but also that ‘lack of tourism knowledge by many municipality departments leads to the underutilisation of many immovable municipal assets’ (Dlomo & Tseane-Gumbi, Citation2017:8).

3. The Overstrand tourism economy

By 2017 the Overstrand Local Municipality, with Hermanus its largest town, was estimated to have a population of 91 190 of which 43% are classed as African (black), 29% as Coloured and 28% white (Western Cape Government, Citation2017). The fastest growth is amongst the African community because of recent in-migration from Eastern Cape (Overstrand Local Municipality, Citation2018a). In many respects Hermanus remains spatially segregated along racial lines. Its long-established ‘Coloured’ settlements of Mount Pleasant and Hawston and the newer ‘black’ township of Zwelihle are separated from the more affluent (mainly white residential) areas of the town.

Hermanus represents the economic heart of the Overstrand municipality. The town is one of several seaside resorts that evolved in South Africa from the nineteenth century onwards. The initial historical establishment of settlement in the area occurred during the mid-nineteenth century with its local economic base being fishing and whaling. Indeed, Hermanus would be categorised as a ‘traditional’ as opposed to an integrated resort (Kauppila, Citation2010) as it has its own distinct development history with settlement before the tourism era. The transition from unassuming fishing village to resort town began slowly during the late nineteenth century with the locality’s discovery by health tourists as well as pleasure seekers. The attractions of the Hermanus climate, beaches and sea angling explain its progressive consolidation as a pleasure tourist resort during the first decades of the twentieth century. By the 1920s Hermanus was likened to the French Riviera in appeals to international tourists (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2020a). Publicity material issued by the South African Railways in the 1930s targeted to attract visitors from outside South Africa described the town as a ‘holiday resort and centre of world-wide fame for its sea fishing’ (Carlyle-Gall, Citation1937:16). Further, it was elaborated that Hermanus

has become to the South African rodster what St Andrews is to the British golfer, while the man making his cast from the rock beside you may hail from New Zealand, from the British Isles, from America or Rhodesia, so widespread is the repute of the coast here as an angler’s paradise. (Carlyle-Gall, Citation1937:24)

During the apartheid period Hermanus consolidated its reputation as a family destination for domestic travellers and continued to boast its attractions of ‘champagne air’, safe bathing and as one of the world’s best sea-fishing locations. A watershed moment for local tourism occurred during the 1980s with the fortuitous return of Southern Right Whales to the Hermanus coast (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2020a). This allowed Hermanus and the surrounding towns of the Overstrand to be reinvented as an ecotourism destination and subsequently branded as the ‘Whale Coast’ (Lloyd, Citation2018). Bordered by the Atlantic Ocean contemporary tourism development in the Overstrand is part of the ‘blue economy’ and of wider national government initiatives for expanding coastal and marine tourism (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2019b).

Within the municipality are several tourism destinations such as Kleinmond, Betty’s Bay, Stanford and Gansbaai as well as Hermanus. Beyond beaches and spectacular natural scenery the municipal area includes wine farms, numerous natural protected areas offering hiking and camping opportunities as well as an array of marine activities, most notably whale viewing and cage diving with great white sharks. Adventure tourism is of such growing significance for the municipal tourism economy that Hermanus seeks to claim the title of South Africa’s adventure tourism capital. Shark-cage diving is a popular ‘bucket-list’ item for many long-haul international tourists particularly from Europe and North America (McKay, Citation2020). Other adventure tourism activities in the area include canopy tours, ziplining, parasailing, sand boarding, tubing and quad biking. Food tourism is of importance and signalled by the UNESCO announcement in November 2019 that Overstrand was designated Africa’s first Creative City of Gastronomy.

The major characteristics of the local tourism economy are captured on . The Overstrand exhibits a strong tourism economy which is heavily leisure-based and with only a relatively small, albeit growing, component of business tourism. As compared to the national pattern of trip visits the category of visiting, friends and relatives is far less significant in this locality. The tourism economy is dominated by domestic trips representing the continuation of a long history of Hermanus evolution as a domestic tourism resort (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2020a). It is observed, however, that across the period 2001–18 there is a relative reduction in the overall share of domestic as opposed to international trips from 80.1% in 2001 to 74.1% by 2018. This is a general reflection of the downturn in domestic travel since 2010 linked to the decline of the national economy; most domestic visitors are either from the Western Cape or Gauteng. International tourism is a rising component in the local economy with leading source markets being Germany, United Kingdom, USA and Netherlands. Chinese tour groups are also noted as expanding in numbers particularly in Hermanus. The critical significance of tourism for the local economy is signalled by the finding that tourism is estimated to contribute 37.2% of local GDP. This makes the Overstrand local municipality South Africa’s fourth most tourism-dependent economy.

Table 1. Overstrand municipality: key indicators, 2018.

Research undertaken on the development and ownership structure of the Overstrand tourism economy reveals that the early historical evolution of tourism in the area was almost exclusively dominated by white entrepreneurs (Rogerson, Citation2019; Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2019c). The dominant role assumed by white entrepreneurs in the Hermanus tourism economy continued during the apartheid period and following democratic transition the ownership structure of the key components of the tourism economy remained little changed. The accommodation services economy of Hermanus includes (November 2018) eight hotels and over 150 guest houses or lodges as well as 292 advertised Airbnb listings; all are in white ownership. In terms of tour services Trip Advisor lists 27 Hermanus tour companies with only one black-owned enterprise. In restaurants the commanding heights of the local food tourism economy are exclusively in white ownership; the only black-owned tourism restaurant is a community-owned facility which has been established at the local attraction of the penguin colony. Finally, in relation to the area’s leisure tourism attractions, including ecotourism, wine, food and adventure, all are currently operated and owned by white entrepreneurs. Conference tourism is focused on the corporate-owned Arabella hotel and golf course under the ownership of the African Pride Group, part of Protea/Marriott.

4. Leveraging municipal assets for inclusive tourism

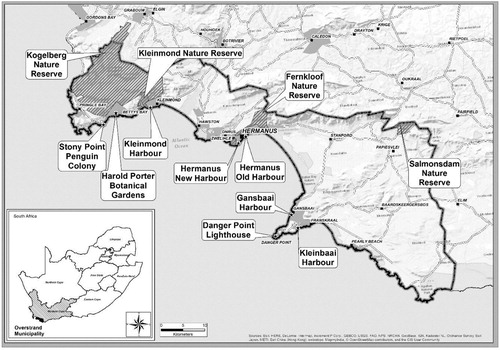

It is evident the existing ownership structure of the local tourism economy is overwhelmingly white-dominated and cannot be described as inclusive. The urgency for development planning as a whole in this municipality to become more ‘inclusive’ was underlined during 2018 by mass civil protests which were triggered partly by the absence of economic livelihood opportunities and with youth unemployment rates exceeding 30%. Significantly, on TripAdvisor several of the ‘top things to do’ in the Overstrand relate to assets owned by the local municipality, a finding which underscores the significance of understanding the question of leveraging for inclusion. In line with the government-wide framework on immovable assets the Overstrand Municipality has adopted an asset management policy with one goal to fulfil the constitutional mandate for ‘promotion of social and economic development’ (Overstrand Local Municipality, Citation2018b). This effectively aligns asset management with the essential goals of municipal LED programming. The list of municipal assets for the Overstrand includes harbours, nature reserves, caravan parks, beaches, a botanical garden, cliff path, penguin colony and a lighthouse. shows the local geography of the core assets.

The stakeholder interviews and documentary sources disclosed that in recent years several initiatives for building a more inclusive Overstrand tourism economy have been launched by different institutional actors. The first chapter in terms of planning initiatives targeted at broadening the engagement of entrepreneurs from previously disadvantaged communities in local tourism relates to the activities of the Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency (OLEDA) which was a ‘private company owned by the Overstrand Municipality’ (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2008:2). The establishment of OLEDA was part of the wave of LEDA establishments that occurred in South Africa during the period 2000–10 giving support to place-based local development initiatives (Lawrence & Rogerson, Citation2018, Citation2019). OLEDA’s core business was to support local government in respect of the objective of promoting social and economic development. All OLEDA’s approved projects were incorporated in the IDP of Overstrand Municipality (which was constituted in 2000) and aligned ‘with Local Economic Development strategies as strategic thrusts for local economic development’ (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2008:3).

The vision of the leadership of OLEDA was ‘the Overstrand municipal area will be the most sustainable/responsible investment and tourism destination in the Western Cape’. The project scoping undertaken by OLEDA identified high potential projects which would serve as ‘primary or key projects’ of operations. Among its projects several related to tourism and with potential for opportunities to be leveraged for entrepreneurs from previously disadvantaged communities. First, was the upgrading of a municipal caravan park and holiday resort situated on the beach at the Palmiet River lagoon outside Kleinmond. With its picturesque seaside location OLEDA argued the ‘facility is totally underutilized and has very high potential to be developed as a tourist destination to the wider public’ (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2008:4). The park comprises 100 caravan sites and 70 camping sites. The proposed upgrade would occur against a backdrop of a poor economic climate in South Africa reflected in the downturn in domestic tourism and of local travellers downscaling to lower-cost holidays including camping tourism (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2020b). It was argued the upgrading of Palmiet in order to offer clean, well-maintained caravan and camping facilities was attractive in providing ‘holiday accommodation that can be rented on a short term basis’ (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2008:21).

A second group of projects proposed for Hawston were targeted explicitly ‘to make a significant contribution to the socio-economic transformation process’ as well as ‘create and stimulate economic empowerment opportunities’ (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2008:29). During 2006 proposals were made to use certain heritage assets in Hawston and establish a local museum as a tourism product but this project never materialised (Overstrand Heritage Landscape Group, Citation2009). OLEDA proposed a mixed-use development on municipal land, a defunct caravan park located next to the Hawston Blue Flag Beach, with proposals for a hotel as well as golf links development. The area enjoys an Olympic-size swimming pool maintained by the municipality which is utilised by the general public, and especially the local community, for recreational purposes. OLEDA sought to facilitate the preparation of a development plan for the area, feasibility study and the process of securing development rights. Two other proposed projects in Hawston were for a marine aquaculture node (that potentially might have tourism spin-offs) and the Hawston Gateway on unused land to make it the gateway to Hermanus for travel from Cape Town. OLEDA identified Hawston ‘as a potential tourist destination in the Overstrand area’ and its projects would serve as an opportunity to develop small local businesses which would benefit Hawston residents. Another tourism proposal was for a camping area at Hawston (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2009).

Notwithstanding the rich potential development opportunities identified by OLEDA for tourism development as a whole as well as creating business opportunities for members of previously disadvantaged communities little progress occurred. OLEDA experienced a strained relationship with the municipality and frustrated by its inability to function as a development agency because of the red tape of municipal processes. In 2010 OLEDA operations were closed down with full responsibility for economic and social development reverting to the municipal LED department. The interviews revealed that ‘a lot of proposals have not happened’ and ‘there were repeated missed and lost opportunities’ as the municipality ‘stopped a lot’ and did not move forward proposals to the stage of putting out tenders. It was stressed the municipality was not entrepreneurial and ‘one of the most conservative’ in terms of its planning. Other limiting factors on the progress of tourism projects proposed for Hawston related to lack of essential community buy-in (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2009). OLEDA recognised the threat posed by ‘high and complex community expectations’ surrounding proposed developments in Hawston (Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, Citation2008:33) and certain project proposals failed to reach fruition ‘because of community divisions and conflicts’.

With the ending of OLEDA the focus is upon the status of other tourism development proposals for inclusion. The redevelopment of Kleinmond Harbour and its mixed use waterfront is of note (Gotz, Citation2014). In addition to the waterfront the project involves a heritage element linked to the restoration of cottages of the Visbaai fishing community (mainly Coloured households) whose village was demolished after the community was forcibly removed because of the Group Areas Act (Gabriel Fagan Architects, Citation2008). The interviews revealed progress has been limited on this ambitious project with explanations offered that ‘it is a divided community not knowing where to take the development potential of the area’. Mistrust between the private sector property developer, the local fishing community as well as heritage groups resulted in the project stalled with neither the developer or community prepared to commit. Over a period of 10 years the developer sought to engage the local community and reach a contractual agreement (including establishment of a Trust) but this ‘was reneged on three times by the community’. Further frustrating the progress of this project was ‘internal politics’ within the municipality surrounding planned developments at the harbour.

Missed opportunities for tourism development also occur beyond Kleinmond. Progress in redevelopment of Hermanus New Harbour slowed because of an inter-governmental dispute between the Western Cape province and national government over the management of 12 provincial harbours including Hermanus (Kaiser Associates, Citation2012). The province alleges that it is unconstitutional for these assets to be under the control of national government which it charges with ‘gross mismanagement’ and the serious degradation of these public assets negatively impacts socio-economic opportunities in the fishing, aquaculture and tourism sectors. At Danger Point Gansbaai problems surround Portnet’s ownership and control of the site which includes the Lighthouse and surrounding heritage area. Interviewees suggest Portnet has ‘blocked Whale Coast tourism’ and tourist visits to the Lighthouse are not guaranteed as it is closed on weekends and public holidays.

At Betty’s Bay one project has moved forward for a community-owned restaurant at the entrance to Stony Point penguin colony, one of only two land-based penguin colonies in the world. In 2005 details of the project were first announced. Following several years of extensive public participation and the challenges of amending site plans the project came to fruition in April 2015 when the Stony Point Eco-Centre and restaurant opened. The project was funded by the national Department of Tourism with additional support from the Western Cape Department of Tourism Extended Public Works Programme for constructing a themed visitor information centre, tearoom and heritage site for whaling history. The project is a community initiative and a partnership with the local Mooiuitsig Community Trust, which holds the rights to manage the restaurant and eco-centre. The restaurant was described by interviewees as ‘a vision of the community’ with Cape Nature the custodian of the initiative. The project experienced difficulties concerning the operations of the restaurant. By 2016 municipal officials were cautioning about ‘difficulties’ at the restaurant attributed ‘mostly to poor management’ and ‘that it is a sticky situation to administer due to the Community Trust’. Field visits in 2018 confirm the opinion of interviewees that the project ‘is not operating at its full potential’.

At Hawston missed opportunities on other tourism proposals were accounted for by ‘ideas not being seen through due to disagreements within the community’. Private sector interviewees suggested that the municipality itself ‘don’t have an understanding of tourism’ as is reflected by the fact that ‘they do not see blacks as tourists’ and are ‘not addressing the major issues such as seasonality’. Core problems surround municipal ‘red tape’ and complaints about protracted periods of delay by Council in making decisions on proposed business developments. The frustrations of private sector entrepreneurs about Council are captured in the statement that ‘they would rather delay everything rather than do the work’ in terms of development facilitation. These responses underline the municipality’s limited entrepreneurialism towards business development and that a major part of its LED operations focus on public works poverty alleviation projects. From the private sector perspective there is minimal focus on investor needs and that municipality ‘don’t take LED seriously’. It was argued the municipality ‘do not know how to facilitate things’ for private investment and the town planning department is ‘a tourism hindrance as business plans either can take over a year to be passed or be lost altogether’.

Notwithstanding the above criticisms directed at the local municipality there have been a number of municipal-led initiatives targeted at assisting the entry of potential black entrepreneurs into tourism. The IDP review acknowledges ‘the lack of transformation in tourism business ownership and opportunities’ as one of the most significant challenges facing Overstrand. It seeks to address this through enhanced access to training and opportunities for previously disadvantaged communities (Overstrand Local Municipality, Citation2018a:66). Cape Whale Coast marketing has hosted free tour guide training courses for community members but few attendees complete the entire course and therefore do not receive certification. Overstrand tourism marketing indicated that ‘we have been trying for two years to register people for tourism initiatives but in many cases they start something and then leave it for something new before it has really got off the ground’. In one statement about the traditionally fishing village of Hawston the municipality identified ‘fishing as something that the Coloured community could do with tourists and training was offered but nobody was interested’. Another initiative at Fernkloof Nature Reserve involves the municipality training four black rangers as field guides to assist tourists, seeing this project as a platform for trainees to move on to other tourism entrepreneurial endeavours. At municipal Blue Flag beaches contracts are awarded during the tourist season to black entrepreneurs for renting-out umbrellas and chairs at the beaches as well as training offered to local community members as beach stewards. The municipality aims to use these basic tourism opportunities and offer further training to assist community members into other more full-time avenues for tourism entrepreneurship.

In terms of explaining the minimal involvement of local black entrepreneurs in the Hermanus tourism economy, the views of the one successful black tour operator are instructive. His business was founded in 2012 on ‘a passion for tourism’. The absence of other black tourism entrepreneurs was attributed to ‘Mentally they want to work for someone else. People are too lazy to start something’ as well as ‘it is very risky to start a business’. In addition, it was argued government ‘does not send the right message’ as ‘they want to be elected in 2019 so they promise free housing, free education and job creation. The government will do everything so there is no need [for blacks] to make the effort to start a business’. In a further statement ‘people are looking for something to come to them’. The entrepreneur acknowledged support he had received in business development from the municipality for training courses: ‘Cape Whale Coast marketing people have been very helpful in assisting with training and courses … they send out emails with course updates’. Among difficulties facing local potential entrepreneurs are access to finance and lack of direct support for business development, issues which mirror the national needs analysis for tourism SMMEs (Department of Tourism, Citation2016).

The discussion now shifts beyond initiatives to directly engage and promote black entrepreneurs in the Overstrand tourism economy and instead focuses upon expanded involvement of black entrepreneurs in supply chains associated with key municipal tourism assets. In its procurement operations the Overstrand municipality follows national and provincial guidelines. The municipal IDP states in meeting its economic development goals it would put in a place a process for steering the procurement process to favour emerging service providers (Overstrand Local Municipality, Citation2018a). Further, following national policy directions, the focus is on capacity building with the long-term aim of building the competitiveness of service providers. Tender processes are standard in terms of advertising using a variety of forms of communication; the municipality organises training linked to opportunities. Service providers are encouraged to register on the municipal data base and a separate emerging service providers data base for training and other opportunities. The most recent review documentation of the municipal IDP identifies as a response to the risk of deteriorating economic and social conditions ‘making use of supply chain as an economic lever’ (Overstrand Local Municipality, Citation2018a:31).

Key stakeholders confirmed ‘there is a lot of goodwill from Overstrand tourism to engage with local black entrepreneurs’ albeit that the municipality’s engagement must comply with the Municipal Financial Management Act. The interviewees disclosed use of national as well as provincial databases for procurement and in terms of council procurement ‘they have contractors on the database who know how to comply’. Although the extensive supplier data base is categorised as SMME or BEE compliant, they ‘have found that there is only a relatively small number of reliable companies’. Nevertheless, the research revealed limited opportunities in the supply chains of municipal assets. The services of black supplier enterprises are contracted for various different capacities; the clearance of alien vegetation (Fernkloof), building contracts (Harold Porter Reserve), general repair and maintenance (including of cliff paths) and provision of catering services at municipal functions including at municipal assets. At least one catering enterprise is now established and growing as a consequence of preferential procurement linked to municipal assets.

5. Conclusion

The building of inclusive tourism is an international challenge. In South Africa the policy questions around inclusion relate especially to extending participation in the tourism economy of previously disadvantaged groups under apartheid. National government seeks to promote inclusion through innovating a range of supply side interventions to assist black entrepreneurs. A new policy focus is leveraging the potential of state assets to promote greater participation either as tourism entrepreneurs or in supply chains. This new policy focus directs attention to a little discussed aspect of municipal activities, namely the management of immovable assets.

The Overstrand tourism economy is white-dominated and its benefits remains little changed from the apartheid years. The municipality, however, has a significant basket of municipal assets which can be leveraged for tourism development including for the potential benefit of entrepreneurs from disadvantaged communities. The record is that several of these assets are underperforming for the local tourism economy for a number of reasons. These include lack of entrepreneurialism and of risk-taking by Council, bureaucratic delays and red tape surrounding approval of development projects, a seeming lack of appreciation by the municipality of the real potential of these assets for tourism, and divisions and conflict within local black and coloured communities which repeatedly thwarted the progress of several carefully crafted project proposals for local tourism entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, the under-performance of municipalities in maximising the impacts of potentially valuable tourism assets cannot be understood only as the result of problems at the municipal level. Arguably, in many cases the maximisation of municipal assets is constrained by the fact that assets are in but not of the municipality. Critical limits are imposed by the fact that ‘municipal’ assets are either managed/controlled either by other tiers of government or by parastatal agencies. Efforts to use assets for tourism development are stymied by lack of inter-government cooperation or ambiguity as to which level of government was responsible. In terms of addressing inclusivity in Overstrand tourism these multiple factors must be appreciated as contributing to the slow pace of transformation.

Beyond direct involvement in tourism are a handful of opportunities for emerging black entrepreneurs to engage as suppliers linked to municipal assets; as yet these provide only limited avenues for growing black-owned businesses. In order to maximise such opportunities interventions are required in terms of supplier development support. Nevertheless, a key conclusion – at least for the case of the Overstrand – is that procurement processes around state assets in tourism are of minor significance for developing black SMMEs. More critical is the need to address blockages around the maximisation of municipal assets for further tourism growth as a whole as shown by the historical experience of missed opportunities. Arguably, among missed opportunities have been several initiatives with real potential to expand the business development of entrepreneurs from marginalised communities. In final analysis the need is urgent for municipalities to change the mindset from one of simply maintaining municipal assets to instead of striving continuously to maximise their potential for local economies. Overall, across international scholarship on inclusive tourism further exploration of municipal asset management is merited.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, D, 2019. Transformation of the tourism sector in South Africa: A possible growth stimulant? GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 26(3), 821–830.

- Bakker, M, 2019. A conceptual framework for identifying the binding constraints to tourism-driven inclusive growth. Tourism Planning & Development 16(5), 575–590.

- Bakker, M & Messerli, H, 2017. Inclusive growth versus pro-poor growth: Implications for tourism development. Tourism and Hospitality Research 17(4), 384–91.

- Biddulph, R & Scheyvens, R, 2018. Introducing inclusive tourism. Tourism Geographies 20(4), 583–8.

- Bukula, SM, 2018. What SMEs can do to increase their inclusion in the tourism value chain. In Sustainable Tourism Partnership (Comp.), The responsible and sustainable tourism handbook: South Africa. Vol. 6. Alive2green, Cape Town, pp. 88–91.

- Butler, G & Rogerson, CM, 2016. Inclusive local tourism development in South Africa: Evidence from Dullstroom. Local Economy 31(1–2), 264–81.

- Carlyle-Gall, C, 1937. Six thousand miles of sunshine travel over the South African Railways. South African Railways and Harbours, Johannesburg.

- Department of Public Works, 2005. Government-wide immovable asset management policy. Department of Public Works, Pretoria.

- Department of Public Works, 2008. Immovable asset management in national and provincial government: Guideline for custodians. Department of Public Works, Pretoria.

- Department of Small Business Development, 2018. Functions aligned to the mandate of DSBD. DBSD, Pretoria.

- Department of Tourism, 2016. SMME development project management unit. Unpublished report. Department of Tourism, Pretoria.

- Department of Tourism, 2018a. National tourism sector strategy 2016–2026. Department of Tourism, Pretoria.

- Department of Tourism, 2018b. Baseline study on the state of transformation in the tourism sector. Department of Tourism, Pretoria.

- Department of Tourism, 2018c. Minutes: national tourism sector strategy implementation work stream. Department of Tourism, Pretoria, 3 August.

- Dlomo, TO & Tseane-Gumbi, LA, 2017. Hitches affecting the utilization of immovable municipal assets in achieving tourism development in East London city, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6(3), 1–11.

- Gabriel Fagan Architects, 2008. Kleinmond Visbaai harbour redevelopment: Sustainable job creation for a coastal fishing community. Report prepared by Gabriel Fagan Architects, Cape Town.

- Giddy, JK, Idahosa, LO & Rogerson, CM, 2020. Leveraging state-owned nature-based assets for transformation and SMME development: Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa. In JM Rogerson & G Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 299–316.

- Gotz, L, 2014. Cape’s Kleinmond harbour upgrade, 27 February. https://www.property24.com/articles/capes-kleinmond-harbour-upgrade/19417 Accessed 10 July 2019.

- Jenkins, CL & Henry, BM, 1982. Government involvement in tourism in developing countries. Annals of Tourism Research 9, 499–521.

- Kadi, J, Plank, L & Seidl, R, 2019. Airbnb as a tool of inclusive tourism? Tourism Geographies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1654541.

- Kaganova, O, 2010. Government management of land and property assets: Justification for engagement by the global development community. Urban Institute Center on International Development and Governance, Washington, DC.

- Kaganova, O & Kopanyi, M, 2014. Managing local assets. In C Farvacque-Vitkovic & M Kopanyi (Eds.), Municipal finances: Guidebook for local governments. World Bank, Washington, DC, pp. 275–324.

- Kaiser Associates, 2012. Report on the economic and socio-economic state and growth prospects of the 12 proclaimed fishing harbours in the Western Cape. Report to Department of Premier, Western Cape Government, Cape Town.

- Kauppila, P, 2010. Resorts and regional development at the local level: A framework for analyzing internal and external factors. Nordia Geographical Publications 39(1), 39–48.

- Lawrence, F & Rogerson, CM, 2018. Local economic development agencies and place-based development: Evidence from South Africa. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series 41, 29–43.

- Lawrence, F & Rogerson, CM, 2019. Local economic development agencies and peripheral small town development: Evidence from Somerset East, South Africa. Urbani Izziv 30(Supplement), 144–157.

- Lloyd, F, 2018. Cape Whale Coast: A tourism marketing strategy 2018–2022. Report prepared for Overstrand Local Municipality, Hermanus.

- McKay, T, 2020. Locating great white shark tourism in Gansbaai, South Africa within the global shark tourism economy. In JM Rogerson & G Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 283–98.

- Nel, E & Rogerson, CM, 2016. The contested trajectory of applied local economic development in South Africa. Local Economy 31(1–2), 109–123.

- Overstrand Heritage Landscape Group, 2009. Public participation document: Hawston. Report prepared for the Overstrand Municipality, Hermanus.

- Overstrand Local Municipality, 2018a. Integrated development plan: 1st review of 5 year IDP (2018/19). Overstrand Local Municipality, Hermanus.

- Overstrand Local Municipality, 2018b. Asset management policy. Overstrand Local Municipality, Hermanus.

- Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, 2008. Application for establishment grant funding and business plan. Report prepared by OLEDA, Hermanus.

- Overstrand Local Economic Development Agency, 2009. Quarterly report: 1 November 2008–30 June 2009. Internal report, OLEDA, Hermanus.

- Rogerson, CM, 2005. Unpacking tourism SMMEs in South Africa: Structure, support needs and policy response. Development Southern Africa 22(5), 623–642.

- Rogerson, CM, 2007. Supporting small firm development in tourism: South Africa’s tourism enterprise Programme. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 8(1), 6–14.

- Rogerson, CM, 2017. Business incubation for tourism SMME development: International and South African experience. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6(2), 1–12.

- Rogerson, CM, 2020a. In search of inclusive tourism in South Africa: Some lessons from the international experience. In JM Rogerson & G Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 147–65.

- Rogerson, CM, 2020b. Using municipal tourism assets for leveraging local economic development in South Africa. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series 48, 47–63.

- Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2019a. Public procurement, state assets and inclusive tourism: South African debates. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 26(3), 686–700.

- Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2019b. Emergent planning for South Africa’s blue economy: Evidence from coastal and marine tourism. Urbani Izziv 30(Supplement), 24–36.

- Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2019c. Tourism, local economic development and inclusion: Evidence from Overstrand local municipality, South Africa. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 25(2), 293–308.

- Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2020a. Resort development and pathways in South Africa: Hermanus 1890–1994. In JM Rogerson & G Visser (Eds.), New directions in South African tourism geographies. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 15–32.

- Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2020b. Camping tourism: A review of recent international scholarship. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 28(1), 333–349.

- Rogerson, CM & Saarinen, J, 2018. Tourism for poverty alleviation: Issues and debates in the global South. In C Cooper, S Volo, B Gartner & N Scott (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of tourism management: Applications of theories and concepts to tourism. Sage, London, pp. 22–37.

- Rogerson, JM, 2019. The evolution of accommodation services in a coastal resort town: Hermanus, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 8(5), 1–17.

- Saito, N, Ruhanen, L, Noakes, S & Axelsen, M, 2018. Community engagement in pro-poor tourism initiatives: Fact or fallacy? – Insights from the inside. Tourism Recreation Research 43(2), 175–185.

- Scheyvens, R. 2011. Tourism and Poverty. Routledge, London.

- Scheyvens, R & Biddulph, R, 2018. Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies 20(4), 589–609.

- Scheyvens, R & Hughes, E, 2019. Can tourism help to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”?: The challenge of tourism addressing SDG1. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27(7), 1061–79.

- UNWTO, 2018. Global report on inclusive tourism destinations: Model and success stories. UNWTO, Madrid.

- Western Cape Government, 2017. Socio-economic profile: Overstrand Municipality, 2017. Western Cape Province, Cape Town.

- World Bank, 2018. An incomplete transition: Overcoming the legacy of exclusion in South Africa. Report no. 125838-ZA. World Bank, Washington DC.