ABSTRACT

Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) emphasises the role and benefits of local communities in order to promote a sustainable utilisation of natural resources. This study aims to identify and analyse the locally perceived benefits and challenges of CBNRM practices in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. A specific focus is on Communal Area Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE), which has faced challenges due to changes in the political and economic environment in the country. The findings based on a household survey from three wards adjacent to Hwange National Park suggest that community members have negative perceptions on CAMPFIRE largely due to their non-involvement in the decision-making and management of the natural resources. The community members do expect to gain benefits from CAMPFIRE but they do not perceive and experience receiving any. Therefore, they consider facing mainly challenges from the Park, emanating from the current inefficiencies of CAMPFIRE.

1. Introduction

Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) aims to centre the role of local communities in natural resource management (Roe et al., Citation2009). In general, CBNRM is based on the idea that local communities need to participate in the management and have direct control over the use and benefits of natural resources (Child & Grenville, Citation2010; Musavengane & Kloppers, Citation2020). By securing the control and benefits of natural resources local communities are assumed to value and manage them in a responsible and sustainable way (Ostrom, Citation1990; Blaikie, Citation2006). Therefore, local involvement and perceptions of the value and practices of CBNRM are crucial to study.

CBNRM has become a popular policy tool and dominant development discourse for environmental management processes especially in southern Africa (Jones & Murphree, Citation2004), where wildlife-based ecotourism operations have been increasingly used as a tool to generate community benefits from sustainable use of natural resources (see Hoole & Fikret, Citation2010; Mbaiwa, Citation2015; Moswete & Thapa, Citation2015; Stone, Citation2015). In principle, both CBNRM and ecotourism aim at centralising the local communities and their involvement and benefits from sustainable natural resource management by emphasising need for participation, control and benefit creation (Fennell, Citation2001, Citation2015; Mbaiwa et al., Citation2019). In this respect, the combination of CBNRM and ecotourism development can represent an incentive-based conservation thinking (Swatuk, Citation2005). While there are many success stories of the symbiotic relation between communities and CBNRM with ecotourism initiatives (see Jones & Murphree, Citation2004; Long, Citation2004; Fennell & Weaver, Citation2005), there are also failures.

In general, the key problems originate from poor local involvement, power inequalities and resulting minimal or missing community benefits, which should be addressed based on local views and needs (see Tosun Citation2000, Citation2006; Saarinen, Citation2010; Mbaiwa, Citation2011a, Citation2017). This is crucial because CBNRM is seen in the southern African context often as a concept meant to correct the colonial injustices of the past whereby the rural people were excluded from the management of resources in their communities (Matseketsa et al., Citation2018). During the colonial era, protected areas (PAs) were formulated to forward the global conservation agenda, and laws were promulgated to criminalise traditional practices such as subsistence hunting done by the locals (Ramutsindela, Citation2009; Matseketsa et al., Citation2018) thereby taking away the right of the locals to benefit from the resources in their communities.

In addition to counter the detrimental impacts of colonial practices to African communities, CBNRM has become an increasingly important tool to support the achievement of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and related targets (United Nations, Citation2015), in general, and particularly those that focus on uplifting lives of rural communities and the protection of natural resources (see Saarinen et al., Citation2013). In this regard, the SDGs aim to reduce rural poverty through among other things promoting the sustainable use of resources (Rogerson & Saarinen, Citation2018). Furthermore collaborative resource governance strategies have the potential to help in the achievement of SDGs through reduction of poverty in rural communities and promoting the sustainable use of biodiversity (Spenceley & Rylance, Citation2019). Pro-poor tourism, inclusive tourism and collaborative based community tourism are concept tied to CBNRM practices because of their ability to promote governance of resources by local community members hence they can be advanced for the achievement of SDGs such as no poverty, gender equality, reduced inequalities and partnership for the goals among others (Siakwah et al., Citation2019).

In this paper we argue that the local views, involvement and participation are crucial issues to analyse for the successful management of CBNMR projects (see Blaikie, Citation2006; Saarinen, Citation2019; Musavengane & Kloppers, Citation2020). In Zimbabwe the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) project was introduced in 1982 as a CBNRM practice to ensure that the local community members would benefit from the existing wildlife in their everyday living environment (Ntuli & Muchapondwa, Citation2017). During the years, many ecological and socio-economic benefits largely based on ecotourism developments have been reaped in the conservation of natural resources and in uplifting the well-being of communities (Chigonda, Citation2018). In the last two decades, however, CAMPFIRE projects have been facing major operational constraints due to a number of political and economic challenges facing the country thereby reducing the number of international ecotourists and, thus, benefits accruing to the locals (Mutandwa & Gadzirayi, Citation2007). There are existing studies on CBNRM issues in Zimbabwe, but many of them are general policy-oriented papers or conservation focused, or they are empirically older in respect the current conservation area management situation and tourism system in the country (see Madzudzo, Citation1999; Jones, Citation2004; Child & Grenville, Citation2010).

The main aim of the research is to identify and analyse the perceived benefits and challenges of CBNRM in the Zimbabwean context. The study provides an empirically informed situation analysis on local views on CBNRM developments and practices by participating local communities living adjacent to Hwange National Park. The empirical approach is based on a household survey from three wards adjacent to the Park, which is the largest protected area in Zimbabwe and a major tourism destination in the country and southern African region. Therefore, studying the local views on the management, benefits and costs of the National park is important for the communities but also for the socio-economic development of the country in future.

2. Community-based natural resource management thinking

2.1. Devolution of power and creating local benefits

In southern Africa, CBNRM related policies and implementation practices have taken different forms and shape depending on the needs and situation of a particular country (Mountjoy et al., Citation2016). Related to this, Dyer et al. (Citation2014) have noted that there are several CBNRM programmes in the region. For example, there is the Administrative Management Design for Game Management Areas (ADMADE) and Luangwa Integrated Resource Development Project (LIRDP) in Zambia (DeGeorges & Reilly, Citation2009; Musavengane & Simatele, Citation2016) and Wildlife Integration for Livelihood Diversification (WILD) practice in Namibia (Harrison et al., Citation2014). In addition, Namibian government has established communal conservancies based on trust and co-management (DeGeorges & Reilly, Citation2009; Kavita & Saarinen, Citation2016). According to Hoon (Citation2014) Botswana has community trusts guided by the CBNRM policy promulgated in 2007 by the Botswana parliament (see Mbaiwa et al., Citation2019).

Despite the specific initiative, CBNRM represents a ‘management of resources such as land, forests, wildlife and water by collective, local institutions for local benefit’ (Roe et al., Citation2009: 5). Thondhlana et al. (Citation2015) have noted that in various places around the world local people are part of parks and their surroundings making them an important stakeholder in the conservation of natural resources. Child & Grenville (Citation2010) have argued that most rural African communities live on communal lands where they are politically and also economically excluded from having access to resources in their areas that form the bedrock of their survival. However, people living at the proximity of protected areas often experience costs such as disruption of their agricultural activities, depredation of their livestock, loss of lives as well as spread of diseases from wildlife to livestock among other costs (Mutandwa & Gadzirayi, Citation2007).

There is an increasing need to involve local communities in the management of protected areas to reduce social and economic costs and to ensure that the conservation objectives are achieved (Musavengane & Simatele, Citation2016). Indeed, previous research findings indicate that conservation without local participation and benefit creation often leads to negative outcomes for both protected areas and communities (Ostrom, Citation1990; Muboko & Murindagomo, Citation2014; Musavengane & Simatele, Citation2016). In order to avoid such outcomes, CBNRM entails empowerment of community members and encouraging their participation in decision-making and management of natural resource as well as the devolvement of ownership to the communities integrally involved in resource use (Jones, Citation2004; Gandiwa et al., Citation2013). In addition, the SDGs centralise the local and human well-being in economic development (see United Nations, Citation2015; Saarinen, Citation2020).

In general, CBNRM programmes are aimed at creating economic value for wildlife conservation for the benefit of community members (Chigonda, Citation2018). Opportunities arising from CBNRM include revenue accruing to the community members, game meat in cases where the trophy animal is edible as well as infrastructural development in the communal areas (Zunza, Citation2012; Harrison et al., Citation2014). Politically and mentally, CBNRM practices can empower local people and allow previously marginalised communities to exercise their collective rights over natural resources and land (Hoon, Citation2014; Chiutsi & Saarinen, Citation2017; Schnegg & Kiaka, Citation2018).

In addition to success, however, Hoole & Fikret (Citation2010) have elucidated that CBNRM experiences in southern Africa involve also failures due to a number of challenges facing specific projects (Blaikie, Citation2006; Mbaiwa, Citation2011b; Dyer et al., Citation2014; Ntuli & Muchapondwa, Citation2017). Corruption by the local committees in accounting for the revenue collected from CBNRM projects as well as lack of transparency in the distribution of benefits is one of the challenges facing CBNRM (Chiutsi & Saarinen, Citation2017). Lack of funding is one of the major challenges facing CBNRM, since they are heavily reliant on donor funding (Mountjoy et al., Citation2016). Donors and other support agencies have been of late focusing their resources to new initiatives such as transfrontier conservation areas (Hutton et al., Citation2005; Ramutsindela, Citation2009). CBNRM practices are too depended on donor funds such that when donors pull out they tend to collapse because of lack of funds (DeGeorges & Reilly, Citation2009). Moreover marginalisation of the local communities in the management of natural resources and the tendency by central government to retain authority in key decision-making and determining how resources will be used is another challenge facing CBNRM (Hoon, Citation2014; Chigonda, Citation2018).

Dyer et al. (Citation2014) have highlighted that major policy failure in the devolution of power and authority in CBNRM practices as a dominant challenge. It is also argued that in Sub-Saharan Africa CBNRM practices are often driven by the need to fulfil personal interest exercise of political power (Nelson & Agrawal, Citation2008). In Namibia the creation of communal conservancies was blamed for the increase in the number of wild animals resulting in competition for grazing land and water between wildlife and livestock (Weaver & Skyer, Citation2003). The ban on trophy hunting and other forms of consumptive wildlife use in some countries greatly diminishes the potential economic returns for communities and creates disincentives for conservation by reducing wildlife’s local economic value (Norton-Griffiths, Citation2007).

Dube (Citation2019) has noted that in communities bordering conservation areas members usually perceive wildlife as a menace that interferes with their day to day lives and destroy their sources of livelihood. CBNRM practices are therefore seen as a potential way in which the local community members can also benefit from the wildlife in their localities and encourage the coexistence of wildlife and humans (see Grobler, Citation2007). Such approaches are credited for creating positive perceptions and awareness among the community members on the benefits they can reap from natural resources in their communities (Musavengane, Citation2019). Rogerson & Saarinen (Citation2018) have observed that CBNRM practices help in the transferring of tourism benefits to local communities and especially the poor rural areas.

2.2. Communal Area Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE)

In the Zimbabwean context the CAMPFIRE has been the flagship programme for the country and also for the wider southern African region (Musavengane & Simatele, Citation2016). In this respect, CAMPFIRE is recognised as the first initiative of CBNRM practices in southern Africa and a number of countries have subsequently borrowed from this initiative after its success to develop their own CBNRM (DeGeorges & Reilly, Citation2009; Musavengane & Simatele, Citation2016). The Programme was introduced in the early 1980s to improve community participation in wildlife conservation and management (Muboko & Murindagomo, Citation2014). More specifically, it was largely created for the purposes of dealing with the surge in human-wildlife conflict (HWC) in communities residing adjacent to protected areas (Harrison et al., Citation2014).

CAMPFIRE replaced Wildlife Industries New Development for All (WINDFALL) project, which was introduced in 1978 with the primary objective of introducing commercial wildlife ranching in communal areas and also to fight human-wildlife conflict (Chigonda, Citation2018). WINDFALL failed due to a number of challenges, such as exclusion of the local people and resulting negative perception of the project as well as unfair distribution of benefits (Muboko & Murindagomo, Citation2014). Contrast to preceding project the CAMPFIRE programme was credited for contributing to the conservation agenda at the same time helping to alleviate poverty in local communities (Tichaawa & Mhlanga, Citation2015).

Currently, CAMPFIRE is governed by the Rural District Councils (RDCs) that are empowered by law to manage revenue derived from selling hunting concessions, trophy fees among others for the benefit of the local communities (Chigonda, Citation2018). RDCs provide the link to national government through the provincial government and they collect hunting fees and distribute the community share through the local CAMPFIRE committees (Gandiwa et al., Citation2013). Harrison et al. (Citation2014) have noted, however, that failure to fully decentralise authority to the local communities has hindered the original design of the CAMPFIRE programme. Therefore, compromises had to be made to devolve authority up to Rural District Councils, which were mandated with representing the local communities. CAMPFIRE project is structured in such a way that there is an elected CAMPFIRE committee that manages the project at a local level and is also responsible for representing the community in dealings with various stakeholders (Balint & Mashinya, Citation2006).

Reduced human-wildlife conflicts have been a result of the education and increase in environmental awareness of local people on how to minimise risk or damage from wild animals in the CAMPFIRE programme (Mapedza & Bond, Citation2006). However, CAMPFIRE has also faced a number of challenges including failure to devolve authority to the local communities, lack of empowerment and participation of local community members as well as elite capture of resources and wildlife-based tourist revenues within Rural District Councils (RDCs) (Harrison et al., Citation2014; Musavengane & Simatele, Citation2016). Barrow & Murphree (Citation2001) have noted that in most cases communities are involved as passive objects of benefits generated and they do not have much to say, i.e. control in the management of resources in their areas (see Chiutsi & Saarinen, Citation2017).

Previous studies have indicated that with regard to CAMPFIRE community members indicate that the control of the programme has been held by a few people who do not have the community at heart and who benefit at the expense of the general community members (Dube, Citation2019). Musavengane & Kloppers (Citation2020) have further posited that CBNRM practices are often characterised by power imbalances between the leaders and community members, which is seen as a source of conflicts between the two groups. Chigonda (Citation2018) has noted that among the participating communities there has been an emergence of a few elite who dominate the whole CBNRM structure and appropriate to themselves the benefits that should be enjoyed by the whole community. Tichaawa & Mhlanga (Citation2015) argued that CAMPFIRE is seen to have generated more of social, i.e. intangible benefits to a community level. Thus, there are less economic benefits accruing to individual households creating negative perceptions by people. In addition, communities go through social and economic changes over time which results in changes in their values and viewpoints necessitating the need to study and understand community perceptions before designing collaborative resource management initiatives (Grobler, Citation2007).

3. Materials and methods

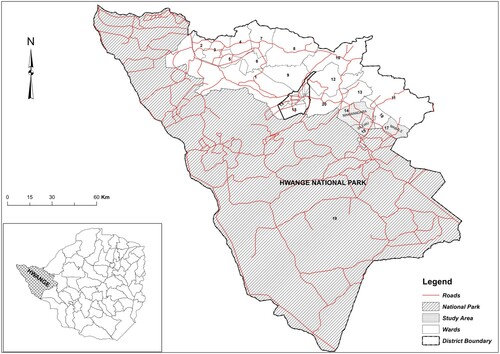

The research was carried out in communities living adjacent to the Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe. The area was first designated as a game reserve in 1928 and currently the park is the largest protected area in Zimbabwe housing a wide variety of wildlife and occupies about 14 600 km2 of land. The area is located in Matabeleland North province (), which is in the agricultural region of the country (Guerbois et al., Citation2013). This research focused on three wards in the Hwange district namely Makwandara (ward 14), Sileu (ward 15) and Mabale (ward 17) due to their close proximity to the National park.

In order to create an overview into the current status and impacts of CAMPFIRE in communities adjacent to Hwange National Park a case study approach with quantitative research methodology was adopted. Household surveys were conducted to three purposively selected wards out of the twenty individual wards in the Hwange district. Respondents were household heads selected using a convenience sampling and the rationale for targeting household heads was because they were assumed to have had an involvement with the operations of CAMPFIRE in their communities. In addition, household heads are culturally expected to approach with questions focusing on land use, natural resource management and related potential challenges (see Chiutsi & Saarinen, Citation2017).

The household surveys were processed by trained Zimbabwean research assistants, which was considered crucial for the fieldwork phase (see Adeyinka-Ojo & Khoo-Lattimore, Citation2018). In the end a total of 200 usable responses were collected from all the three wards by utilising a semi-structured questionnaire with both open ended and closed ended questions. Open ended questions enabled respondents to freely express themselves and to capture their opinion regarding CAMPFIRE practices in their community. The questionnaire contained items that seek to gain an understanding of the important resources for the community members, an evaluation of CAMPFIRE by the community members, benefits the community expects from CAMPFIRE, benefits they have received, challenges they face as well as their proposed solutions to the challenges. Questionnaire items were designed based on a thorough literature review of past studies done on CBNRM practices in Southern Africa. The data was analysed by using descriptive statistics and frequency distribution.

Results from demographic data shows that there were more females (57.5%) than males (42.5%) among the respondents () and the majority of them are educated up to primary level (61.2%), which points to a low level of education in rural areas, in general. The study area is predominated by Nambiya (51%) and Tonga (20.5%) speaking people and the two are regarded as minority languages in Zimbabwe. Due to study areas the dominant languages in Zimbabwe, Ndebele (24%) and Shona (2%), have a lower representation in the research material. Most of the respondents (53%) are in the age group 41-50, and the study sampled 45% of the respondents from ward 17, 32.5% from ward 14 and 22.5% from ward 15.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents (n = 200).

4. Results

Respondents were asked to indicate the key resources they consider having in their community. According to the respondents, firewood, construction materials, wild fruits and grazing land for livestock are the most important resources (). Wild animals, game meat and traditional medicines were regarded as less important based on the Likert scale answers. Still, they were also evaluated in average as important.

Table 2. Importance of resources in the community (n = 200).

Respondents were asked to evaluate the CAMPFIRE project based on their perceptions (). On whether the local CAMPFIRE committee is active, if the locals are given feedback, whether the locals benefit from wildlife through CAMPFIRE and whether CAMPFIRE is effective in reducing HWC, the means were neutral but more tilted towards a disagree scale. Respondents also disagreed on benefits being distributed equally among community members, inclusion of locals in decision-making and on locals getting compensation for destruction by wild animals. This clearly shows that the locals do not believe that CAMPFIRE in their community is beneficial to them and they feel excluded from CAMPFIRE activities. The respondents expressed willingness to actively participate in CAMPFIRE activities as shown by a mean of 2.83 which is aligned to agree scale.

Table 3. Evaluation of CAMPFIRE project (n = 200).

presents responses on benefits the locals expect to get from CAMPFIRE. Respondents expect benefits such as the construction of dams and drilling of boreholes (53%) to provide water to the community, funding of income generating projects (30%), funding provision of social infrastructure (24%), pay school fees for the underprivileged children (18%) and to protect livestock from depredation by wild animals (12%) among other benefits.

Table 4. Benefits expected from CAMPFIRE (n = 200).

The respondents were asked about the benefits they have received from CAMPFIRE. The majority (62%) highlighted that they have received nothing from CAMPFIRE, which may become highly problematic for nature protection and sustainability in a long term. In respect of the benefits, 20% mentioned the construction of community halls, 9.5% construction of grinding mills, 4.5% funding of income generating projects (). Other benefits cited are provision of game meat to community member (4.5%), construction of shops to the community (3.5%), drilling of boreholes (3%) and acquisition of a water engine for a local school in ward 17 (2%). It was also highlighted by community members that of late there are no benefits accruing from CAMPFIRE and the benefits they mentioned were received way back when the project was still viable.

Table 5. Benefits received from CAMPFIRE (n = 200).

While there were identified benefits, also some challenges were faced by community members in CAMPFIRE areas (). In addition to the previously mentioned missing benefits, the respondents cited challenges such as lack of consultation in decision-making (95%), destruction of crops by wild animals (74%), livestock depredation (69.5%), lack of direct benefit to households (65.5%), failure to devolve authority to local communities (64%) and increase in livestock diseases (62%) among other challenges.

Table 6. Challenges faced by communities in CAMPFIRE areas (n = 200).

Respondents were also asked to suggest solutions to challenges they highlighted (). These solutions include activating village CAMPFIRE committees (41%), tightening security in the game park to confine wild animals (28%), CAMPFIRE leadership and community members working closely together (23.5%), compensating community members for loss of livestock and crops caused by wild animals (18%) and educating community members on CAMPFIRE projects (17%). In addition, respondents recommended the construction of water reservoirs, provision of secure grazing lands and dipping chemicals for their livestock (8%).

Table 7. Solutions to challenges faced by communities in CAMPFIRE areas (n = 200).

5. Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that communities living adjacent to the Hwange National Park place importance to a number of resources within their vicinity. Most of these resources are found inside or very close to the park and they include the wild animals, game meat, grazing land for livestock, firewood and construction materials. This is in line with previous studies. Thondhlana et al. (Citation2015), for example, have stated that parks and the surrounding areas endowed with natural resources can sustain the livelihoods of local community members. Furthermore, Chigonda (Citation2018) has concurred that people in Less Economically Developed Countries rely heavily on wildlife for food, shelter and medicines.

However, this study shows critically that the respondents have some negative perceptions towards CAMPFIRE: they do not always see any benefits accruing to them from the Park. This is possibly because there is no active (enough) involvement of the locals in CAMPFIRE, resulting in a knowledge gap concerning the direct and indirect benefits to communities in a form of infrastructure and employment. However, these negative perceptions may simply exist because there are no direct factual, especially financial, benefits to the households and individuals participating in the study. Regardless of these negative perceptions the community members expressed willingness to actively participate in CAMPFIRE activities, if possible. This is in line with Matseketsa et al. (Citation2018) who posited that a governance system where locals are excluded in the management of resources will create negative perceptions among local community members. In this regard Musavengane & Simatele (Citation2016) have noted that if the locals are not involved in the management of resources in their community it is highly likely that they will distance themselves from such initiatives. Similarly, Tichaawa & Mhlanga (Citation2015) have agreed that failure to economically improve the livelihoods of the community members and the lack of compensation for wildlife damages results in a negative perception towards CAMPFIRE. In concurrence with findings of this study Dyer et al. (Citation2014) highlighted that benefits received, costs borne by the locals as well as their involvement in making key decisions has an influence on the local communities’ attitude towards conservation.

The study revealed that people have high expectations from CAMPFIRE and community members may expect ‘life changing’, i.e. significant benefits for their community and household. This is not surpising as the main goal of CAMPFIRE is to provide communities with substantial benefits (Tichaawa & Mhlanga, Citation2015), which creates high expectations for people. Suich (Citation2013) has agreed that lack of sufficient benefits to households and individuals affect the long term survival of the CBNRM projects. Some of the expected benefits (such as presented in ) include construction of dams and boreholes, funding of income generating projects, building of social infrastructure in the community, protection of livestock from wild animals and compensation for destruction caused by wild animals among other benefits. This is consistent with the study done by Zunza (Citation2012) who confirmed that income generating projects such as beekeeping, livestock keeping, gardening projects and handcraft making are perceived as important by communities. Zunza (Citation2012) further opines that opportunities arising from CBNRM include revenue accruing to the community members, game meat as well as infrastructural development in the communal areas. In addition, Lenao et al. (Citation2014) have stated that ecotourism activities in the rural areas concretely raise expectations of the locals to receive tangible benefits.

A majority of the respondents highlighted that they are not receiving any benefits from CAMPFIRE, which is highly alarming and calls for further studies based on a more detailed level. The few benefits mentioned such as construction of community halls, provision of grinding mills and funding of income generating projects were received a long time ago when the project was still viable. Chiutsi & Saarinen (Citation2017) are of the view that locals living adjacent to protected areas have a perception and expectation that tourism brings a lot of benefits but, after all, only a few are benefiting. Related to this, Zunza (Citation2012) has noted that in CAMPFIRE programme areas benefits are seen to be declining, in general, and they are considered as insufficient to support livelihoods of the local communities.

Communities living around protected areas face a myriad of challenges identified in this study. The identified challenges (see ) include insufficient involvement in making decisions regarding the management of resources in the communities, destruction of crops and livestock depredation by wild animals, lack of direct benefits to households, failure to devolve authority to locals and increase in livestock diseases among other challenges. This is in line with Mutandwa & Gadzirayi (Citation2007), for example, who have stated that challenges facing people living at the proximity of protected areas include disruption of their agricultural activities, depredation of their livestock, loss of lives as well as spread of diseases from wildlife to livestock. Chigonda (Citation2018) has also pointed out that marginalisation of the local communities in the management of natural resources and the tendency by central government to retain authority in key decision-making and determining how resources will be used are challenges facing CBNRM. Ntuli & Muchapondwa (Citation2017) are in agreement that CAMPFIRE managed to devolve wildlife management up to the RDCs level only instead of the local communities that bears the cost of wildlife in their areas. Chiutsi & Saarinen (Citation2017) also observed that corruption by the local committees in accounting for the revenue collected from CBNRM projects as well as lack of transparency in the distribution of benefits is one of the challenges facing CBNRM practices in Zimbabwe.

Solutions to the challenges identified in this study as recommended by the community members include re-activating village CAMPFIRE committees, educating the community members on CAMPFIRE, close cooperation between CAMPFIRE leadership and community members as well as providing compensation to community members for losses caused by wild animals. These are highly justified suggestions. Musavengane & Simatele (Citation2016), for example, are in agreement that there is an urgent need to involve local communities in the management of wildlife to reduce social costs and to ensure that the CBNRM practice is effective. Similarly, Harrison et al. (Citation2014) have also concurred that the main aim of CBNRM is to give community members more role to play in the management of natural resources. Tichaawa & Mhlanga (Citation2015) affirmed that locals can only be involved successfully in the conservation of natural resources if they are given the opportunity to make decisions regarding the resources in their communities and if they stand to benefit from the conservation efforts (see Matose & Scotney, Citation2010).

There are some limitations in this study. The results represent three out of twenty wards in the Hwange district, and the selected communities are located close to the Park. In respect to the other wards distance decay may have effects on their relations and perceptions concerning CBNRM practices. Due to the convenience sampling, the results should not be generalised to the analysed wards but considered as an overview on the studied communities. The analysis was mainly based on quantitative and descriptive approach, which can provide unbiased results in general. Still, the questions asked were influenced by the previous research and the researchers motivation on thinking critically on community-conservation relations and benefit sharing practices.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

This study aimed at identifying the current state of CAMPFIRE in relation to the Hwange National Park, by focusing on how the community members perceive the programme and its local practices with regard to benefits they expects and receive and challenges they face. The results indicate that there are negative perceptions among local community members towards the current CAMPFIRE practices and how the programme has been implemented in the study area. These negative views are largely based on the current management situation in which the locals feel sidelined from CAMPFIRE activities and that there are no – financial or material – benefits accruing to them from wildlife conservation. Indeed, there seems to be a wide gap between what the community members expect to receive and what the actual benefits are from CAMPFIRE. Still, the locals perceive wildlife as an important resource that could and should contribute to their well-being and the community development. In order to receive benefits and reduce conflicts, the community members believe that CAMPFIRE can work for them if it is open for their participation.

Historically, many of the local communities in Zimbabwe have once benefited immensely from CAMPFIRE. Thus, they understand the value wildlife could bring to them based on ecotourism operations. Reasons for reduced or vanished benefits and the effects of that for conservation should be studied. They are probably resulting from a combination of internal and external processes. Along with economic challenges, the land reform process changed the policy and development context for CAMPFIRE programme. Nowadays, some of the conservancies that used to support the programme are housing new farmers presenting new kind challenges for conservation and benefit sharing efforts (Mutandwa & Gadzirayi, Citation2007; Guerbois et al., Citation2013). As a result, communities living adjacent to conservation areas no longer benefit from the resources in their vicinity because of the changes in land use patterns, decline in tourist arrivals and the decline in economic activities in the country.

In line with the findings of this research to change the negative perception of community members towards CAMPFIRE it is important to revive the village committees. This would enable community participation, and based on the results there is an urgent need to integrate communities to conservation area management (see Guerbois et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, the community leaders need to be trained on how to co-manage the CAMPFIRE programme with emphasis on the inclusion and participation of the local community members. It was also observed that the community members are affected negatively by wildlife in their area through livestock depredation, spread of diseases from wildlife to livestock and destruction of their crops among other impacts. Based on this, there is a practical need to ensure that such impacts are reduced through buffer zones and proper fencing and also by providing compensating to community members for loss of livestock and crops.

Overall, the effects of nature conservation areas and CAMPFIRE practices on local perceptions and livelihoods are still poorly understood. Further studies should focus on the development of an inclusive benefit sharing model for CAMPFIRE in the current socio-economic circumstances of the country. There is also a need to find better ways to deal with human-wildlife conflict in communities living in proximity to protected areas but not necessarily benefiting from the current Programme and related tourism developments. Otherwise, increasing human settlements at the vicinity of CAMPFIRE areas and other protected sites may become major challenges for nature conservation efforts in future.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by funding from Lupane State University. Many thanks to Mr Phindile Ncube and Mr Nxolelani Ncube from Hwange Rural District council for providing assistance with accessing respondents. The researchers also wish to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adeyinka-Ojo, S & Khoo-Lattimore, C, 2018. Black on brown: research paradoxes for black scholars working in ethnic communities. In Mura, P & Khoo-Lattimore, C (Eds.), Asian qualitative research in tourism. Springer, Singapore, 255–70.

- Balint, PJ & Mashinya, J, 2006. The decline of a model community-based conservation project: governance, capacity, and devolution in Mahenye, Zimbabwe. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 37(5), 805–15.

- Barrow, E & Murphree, M, 2001: Community conservation: From concept to practice. In Hulme, D, Pearce, D & Murphree, M (Eds.), African wildlife and livelihoods: The promise and performance of community conservation. James Curry Limited, Oxford, 24–38.

- Blaikie, P, 2006. Is small really beautiful? Community-based natural resource management in Malawi and Botswana. World Development 34(11), 1942–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.023

- Chigonda, T, 2018. More than just story telling: A review of biodiversity conservation and utilisation from precolonial to postcolonial Zimbabwe. Scientifica, 1–11.

- Child, B & Grenville, B, 2010. The conceptual evolution and practice of community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa: past, present and future. Environmental Conservation 37(3), 283–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000512

- Chiutsi, S & Saarinen, J, 2017. Local participation in transfrontier tourism: Case of Sengwe community in Great Limpopo transfrontier conservation area, Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa 34(3), 260–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2016.1259987

- DeGeorges, PA & Reilly, BK, 2009. The realities of community based natural resource management and biodiversity conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability, 1, 734–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su1030734

- Dube, N, 2019. Voices from the village on trophy hunting in Hwange District, Zimbawe. Ecological Economics 159, 335–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.02.006

- Dyer, J, Stringer, LC, Dougill, AJ, Leventon, J, Nshimbi, M, Chama, F, Kafwifwi, A, Muledi, JI, Kaumbu, J-MK, Falcao, M, Muhorro, S, Munyemba, F & Kalaba, GM, 2014. Assessing participatory practices in community-based natural resource management: Experiences in community engagement from Southern Africa. Environmental Management 137, 137–45.

- Fennell, DA, 2001. A content analysis of ecotourism definitions. Current Issues in Tourism 4(5), 403–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500108667896

- Fennell, DA, 2015. Akrasia and tourism: Why we sometimes act against our better judgement? Tourism Recreation Research 40(1), 95–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1006419

- Fennell, D & Weaver, D, 2005. The ecotourium concept and tourism-conservation symbiosis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 13(4), 373–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580508668563

- Gandiwa, E, Heitkönig, IMA, Lokhorst, AM, Prins, HHT & Leeuwis, C, 2013. CAMPFIRE and human-wildlife conflicts in local communities bordering northern Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe. Ecology and Society 18(4), 7. doi: https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05817-180407

- Grobler, JHF, 2007. Community perceptions of tourism in the Tshivhase area, Limpopo province. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria.

- Guerbois, C, Dufour, AB, Mtare, G & Herve, F, 2013. Insights for integrated conservation from attitudes of people toward protected areas near Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. Conservation Biology 27, 844–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12108

- Harrison, EP, Dzingirai, V, Gandiwa, E, Nzuma, T, Masviele, B & Ndlovu, H, 2015. Progressing community-based natural resource management in Zimbabwe. Sustainability Research Institute Briefing Note Series No. 6. University of Leeds.

- Hoole, A & Fikret, B, 2010. Breaking down fences: Recoupling social-ecological systems for biodiversity conservation in Namibia. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 41(2), 304–17.

- Hoon, P, 2014. Elephants are like our diamonds: Recentralizing community based natural resource management in Botswana, 1996–2012. African Studies Quarterly 15(1), 55–70.

- Hutton, J, Adams, WM & Murombedzi, JC, 2005. Back to the barriers? Changing narratives in biodiversity conservation. Forum for Development Studies 32(2), 341–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2005.9666319

- Jones, B & Murphree, M, 2004. Community-based natural resource management as a conservation mechanism: Lessons and directions. In B Child (Ed.), Parks in transition. Earthscan, London, 233–67.

- Jones, BT, 2004. CBNRM, poverty reduction and sustainable livelihoods: Developing criteria for evaluating the contribution of CBNRM to poverty reduction and alleviation in Southern Africa. In Plaas, CA (Ed.), Centre for applied social sciences and programme for land and agrarian studies (7).

- Kavita, E & Saarinen, J, 2016. Tourism and rural community development in Namibia: policy issues review. Fennia 194(1), 79–88.

- Lenao, M, Mbaiwa, JE & Saarinen, J, 2014. Community expectations from rural tourism development at Lekhubu Island, Botswana. Tourism Review International 17, 223–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.3727/154427214X13910101597085

- Long, S (Ed.), 2004. Livelihoods and CBNRM in Namibia. The findings of the WILD project. Directorate of Environmental Affairs and Ministry of Environment and Tourism, the Government of the Republic Namibia, Windhoek.

- Madzudzo, E, 1999. Community based natural resource management in Zimbabwe: opportunities and constraints. Review of Southern African Studies 3(2), 61–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.4314/rosas.v3i2.22997

- Mapedza, E & Bond, I, 2006. Political deadlock and devolved wildlife management in Zimbabwe: The case of Nenyunga Ward. The Journal of Environment & Development 15(4), 407–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496506294635

- Matose, F & Scotney, W, 2010. Towards community-based forest management in Southern Africa: Do decentralization experiments work for local livelihoods? Environmental Conservation 37(3), 310–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000639

- Matseketsa, G, Chibememe, G, Muboko, N, Gandiwa, E & Takarinda, K, 2018. Towards an understanding of conservation-based costs, benefits, and attitudes of local people living adjacent to Save Valley Conservancy, Zimbabwe. Scientifica, doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6741439

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2011a. Changes on traditional livelihood activities and lifestyles caused by tourism development in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Tourism Management 32(5), 1050–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.002

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2011b. The effects of tourism development on the sustainable utilisation of natural resources in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Current Issues in Tourism 14(3), 251–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.555525

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2015. Ecotourism in Botswana: 30 years later. Journal of Ecotourism 14(2–3), 204–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1071378

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2017. Poverty or riches: who benefits from the booming tourism industry in Botswana? Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35(1), 93–112. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2016.1270424

- Mbaiwa, JE, Mbaiwa, T & Siphambe, G, 2019. The community-based natural resource management programme in southern Africa–promise or peril? The case of Botswana. In Mkono, M (Ed.), Positive tourism in Africa. Routledge, New York, 11–22.

- Mountjoy, NJ, Whiles, MR, Spyreas, G, Lovvorn, JR & Seekamp, E, 2016. Assessing the efficacy of community-based natural resource management planning with a multi-watershed approach. Biological Conservation 201, 120–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.06.026

- Moswete, N & Thapa, B, 2015. Factors that influence support for community-based ecotourism in the rural communities adjacent to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana. Journal of Ecotourism 14(2–3), 243–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1051537

- Muboko, N & Murindagomo, F, 2014. Wildlife control, access and utilisation: Lessons from legislation, policy evolution and implementation in Zimbabwe. Journal for Nature Conservation 22(3), 206–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2013.12.002

- Musavengane, R, 2019. Understanding tourism consciousness through habitus: Perspectives of ‘poor’ Black South Africans. Critical Afrcian Studies 11(3), 322–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2019.1670702

- Musavengane, R & Kloppers, R, 2020. Social capital: An investment towards community resilience in the collaborative natural resources management of community-based tourism schemes. Tourism Management Perspectives 34, 100654. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100654

- Musavengane, R & Simatele, DM, 2016. Community-based natural resource management: The role of social capital in collaborative environmental management of tribal resources in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Development Southern Africa 33(6), 806–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2016.1231054

- Mutandwa, E & Gadzirayi, CT, 2007. Impact of community-based approaches to wildlife management: Case study of the CAMPFIRE programme in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 14(4), 336–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500709469734

- Nelson, F & Agrawal, A, 2008. Patronage or participation? Community-based natural resource management reform in sub-Saharan Africa. Development and Change 39(4), 557–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00496.x

- Norton-Griffiths, M., 2007. Whose wildlife is it anyway? New Scientist 193(2596), 24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(07)60723-4

- Ntuli, H & Muchapondwa, E, 2017. A bioeconomic analysis of community wildlife conservation in Zimbabwe. Journal for Nature Conservation 37, 106–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2017.04.003

- Ostrom, E, 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press, London.

- Ramutsindela, M, 2009. Transfrontier conservation and local communities. In Saarinen, J, Becker, F, Manwa, H & Wilson, D (Eds.), Sustainable tourism in Southern Africa: Local communities and natural resources in transition. Channel View Publications, Bristol, 169–85.

- Roe, D, Nelson, F & Sandbrook, C, 2009. Community management of natural resources in Africa: impacts, experiences and future directions. International Institute for Environment and Development, London, UK.

- Rogerson, CM & Saarinen, J, 2018. Tourism for poverty alleviation: issues and debates in the Global South. Handbook of Tourism Management, 22–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526461490.n4

- Saarinen, J, 2019. Communities and sustainable tourism development: community impacts and local benefit creation tourism. In McCool, SF & Bosak, K (Eds.), A research agenda for sustainable tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, 206–22.

- Saarinen, J, Rogerson, CM & Manwa, H, 2013. In t, development and millennium development goals. Routledge, London.

- Saarinen, J, 2010. Local tourism awareness: Community views on tourism and its impacts in Katutura and King Nehale Conservancy, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27(5), 713–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2010.522833

- Saarinen, J (Ed.), 2020. Tourism and sustainable development goals: Research on sustainable tourism geographies. Routledge.

- Schnegg, M & Kiaka, RD, 2018. Subsidized elephants: community-based resource governance and environmental (in)justice in Namibia. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 93, 105–15.

- Siakwah, P, Musavengane, R & Leonard, L, 2019. Tourism governance and attainment of the sustainable development goals in Africa. Tourism Planning & Development, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1600160

- Spenceley, A & Rylance, A, 2019. The contribution of tourism to achieving UN sustainable development goals. In McCool, SF & Bosak, K (Eds.), A research agenda for sustainabe tourism. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, 107–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788117104.00015

- Stone, MT, 2015. Community-based ecotourism: A collaborative partnerships perspective. Journal of Ecotourism 14(2–3), 166–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1023309

- Suich, H, 2013. The effectiveness of economic incentives for sustaining community based natural resource management. Land Use Policy 31, 441–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.08.008

- Swatuk, LA, 2005. From “project” to “context”: Community based natural resource management in Botswana. Global Environmental Politics 5(3), 95–124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/1526380054794925

- Thondhlana, G, Shackleton, S & Blignaut, J, 2015. Local institutions, actors, and natural resource governance in Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and Surrounds, South Africa. Land Use Policy 47, 121–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.03.013

- Tichaawa, TM & Mhlanga, O, 2015. Community perceptions of a community-based tourism project: A case study of the CAMPFIRE programme in Zimbabwe. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance 21(Supplement 2), 55–67.

- Tosun, C, 2000. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management 21(6), 613–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

- Tosun, C, 2006. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management 27(3), 493–504. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.12.004

- United Nations, 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030AgendaforSustainableDevelopmentweb.pdf.

- Weaver, LC & Skyer, P, 2003. Conservancies: Integrating wildlife land-use options into the livelihood, development and conservation strategies of Namibian communities. Paper presented at the 5th World Parks Congress of IUCN to the Animal Health and Development (AHEAD) Forum, 8–17 September, Durban.

- Zunza, E, 2012. Local level benefits of CBNRM: The case of Mahenye Ward. University of Zimbabwe, Harare.