ABSTRACT

Development corridors have recently gained momentum as territorial tools to attract flows of global capital into agricultural value chains. As this includes the controversial blending of public with private funding for investments into farmland, the integration of smallholders in large-scale operations is increasingly promoted as legitimatory practice. With this article, we discuss the role of finance in shaping such value chain arrangements. Using a spatially sensible financialisation perspective, we present two investment cases that have touched ground as reaction to the promotion of the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT). We assess how finance unfolded along territorial (corridor region and investment origin) and relational (investment chain and value chain) spatialities, to scrutinise the tensions and fragile outcomes that were co-constituted by mixed financial and moral investment imperatives. This helps to understand whether, why, and with what consequences smallholders can benefit from corridor-related investments.

1. Introduction

With the interrelated food and finance crises (2007/08), the agricultural sector has returned onto the agenda of national planning, international development, and global capital investments. Same rediscovery of agriculture as field of development intervention as well as investment opportunity, was further accompanied by a general return towards regional planning to facilitate and govern the increased articulation with the global political economy (Smalley, Citation2017; Schindler & Kanai, Citation2019). Ambitious infrastructural projects in the form of agriculture-oriented development corridors have since epitomised this trend in several African regions. Sometimes dubbed as ‘investment corridors’ (Bergius et al., Citation2018:2), the new generation of corridors goes, however, way beyond the conventional understanding as providing solely connectivity through linear, physical infrastructures (Dannenberg et al., Citation2018). Rather, the notion of attracting ‘investments along the agricultural value chain’ (de Cleene, Citation2014:67) has become the most accentuated feature of contemporary corridor-making. Deployed to demarcate territory that can attract flows of global capital, development corridors can hence be understood as territorial tools aimed at financialising agricultural value chains.

In line with this understanding, we address corridor-making and its implications for integrating smallholders into value chains with a distinct perspective on the role of finance. Based on the case study of SAGCOT, two farmland investments are analysed. To adhere to financial and at the same time moral investment imperatives, both large-scale farms integrated smallholder farmersFootnote1 into their respective value chains. Our qualitative research highlights how a perspective on finance can add to explaining whether, why, and especially with what consequences farmland investments along SAGCOT have led to the integration of smallholders into value chains.

Conceptually, we draw from financialisation literature and adopt Pike & Pollard’s (Citation2010) approach on the economic geographies of financialisation. The spatial sensibility of this approach allows to differentiate the complexity of territorial and relational spatialities under which finance touched corridor territory. We use this to explain emerging tensions and paradoxes between large investments and smallholders beyond a confined land grabbing perspective (Pedersen & Buur, Citation2016). We show that these tensions can go as far as to existentially jeopardise the efforts of letting smallholders benefit from development corridors on the long run.

We structure this article as follows. We introduce how financialisation processes along agricultural value chains are promoted in practice and how they are discussed in the literature. We then explain our conceptual framework for researching the economic geographies of financialisation. After explaining our methodology, we use our framework to discuss two case studies. Finally, we conclude by arguing why a financialisation perspective on value chains can add to understanding the terms of smallholder integration along development corridors.

2. Financialisation and agricultural value chains

With vast empirical evidence on what Epstein (Citation2005:3) popularly defines as ‘the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of domestic and international economies’, interest on financialisation has gained widespread attention. Financialisation perspectives serve as epistemic entry point to understand contemporary capitalism and are used by scholars to understand the rising relevance of finance from the global political economy down to everyday life. While the theoretical foundation and conceptual applicability of financialisation is often criticised for its fuzziness (Ouma, Citation2014; Christophers, Citation2015), financialisation research can be understood as an inter-disciplinary heuristic and rallying point (Fuchs et al., Citation2013).

Regarding the agricultural sector, financialisation has indeed become such a rallying point. Despite the long history of finance in agriculture (Martin & Clapp, Citation2015), the 2007/08 food and finance crises have elevated the focus on financialisation processes (Clapp, Citation2014). Research on the ‘new enclosures’ (White et al., Citation2012), the ‘corporate food regime’ (McMichael, Citation2012) and the financial networks and actors invested in agriculture (Borras et al. Citation2020; Kish & Fairbairn, Citation2018) composes a body of literature incorporating financialisation as a meta-perspective for understanding agricultural production and trade. This literature differentiates two broader phenomena: financialised commodities and financialised farmland (Fuchs et al., Citation2013).

Work on financialised commodities shows that particularly value chains for globally traded cash crops are increasingly financialised through the price mechanisms of derivative markets. Far beyond their financial sphere, global derivative markets have transformed how and to the favour of whom value chains are organised (Newman, Citation2009; Bargawi & Newman, Citation2017; Staritz et al., Citation2018). Here, value chains resemble translation devices for financialisation processes from global markets in their most financial form towards local trading and production in its most physical form (Purcell, Citation2018).

Rather indirectly, financialised farmland, and with that the second phenomena, does affect agricultural value chains as well. With the rediscovery of farmland as an alternative asset class (Ducastel & Anseeuw, Citation2017; Ouma, Citation2020), a ‘farmland investment boom’ (Fairbairn, Citation2014:777) or the ‘finance-farmland-nexus’ (Ouma, Citation2016:82) has led to what is often problematised as a ‘global land rush’ (McMichael, Citation2012; Pedersen & Buur, Citation2016).

The financialisation of farmland relies foremost on complex transnational ‘investment chains’ (Kish & Fairbairn, Citation2018:573) or ‘investment webs’ (Borras et al. Citation2020:1). Constituted of financial actors such as equity investors, financial intermediaries, and asset managing firms, these networks are however not only providing capital, but also setting the investment’s financial (e.g. revenue creation, investment horizon) and moral (e.g. social or environmental impact) imperatives (Kish & Fairbairn, Citation2018). In order to enhance particularly the moral performance of farmland investments and pre-emptively oppose accusations of neo-colonial forms of land grabbing (Bluwstein et al., Citation2018), the integration of smallholders into large farms’ value chains has since established as a widely applied legitimatory practice (Kirsten & Sartorius, Citation2002; Brüntrup et al., Citation2018; Sulle, Citation2020). Additionally, when fully commercial investments are not feasible at a given place and time, the moral performance of large-scale farms can become instrumental for attracting subsidizing capital from public or benevolent funders or investors who are seeing a case in creating social impact and/or who are willing to abstain from immediate profits.

On the side of financial actors, morality as a resource of securing and creating financial value is hence an important factor to make investments possible and more profitable. The win-win logic of leveraging synergies between capital accumulation and developmental effects has become a widespread phenomenon in the contemporary development of agricultural value chains in Africa. Hand in hand with the upsurge of value chain-oriented mega-alliances such as the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition or the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (Sulle & Hall, Citation2013; Moseley, Citation2016), an unprecedented landscape of ‘new actors in development’ (Richey & Ponte, Citation2014) is today steering the transformation of African agriculture in this fashion.

This blended mode of financialising agricultural value chains, goes however not without criticism. As Mawdsley (Citation2016) raises, highly speculative financial investments are the main beneficiaries of foreign aid flows into frontier markets. For frontier markets, public and benevolent capital is increasingly pivotal to escort investments as it subsidizes otherwise unprofitable asset classes. Such subsidies, and hence new forms of financialisation, through foreign aid and philanthropic funding tends to be ‘neglectful and wilfully blind to the greater exposure to the risk and volatility that such trends entail’ (Richey & Ponte, Citation2014:8). Particularly in cases where investments fail, frontier markets can ultimately create a vacuum of accountability when the lines of who covers costs and risks and who collects benefits get blurred.

The translation of investment imperatives from financial actors towards everyday farm operations occurs not in an isolated interaction between the financial sphere of investors and farm operators. Rather, the territorial setting of farmland investments is co-constitutive to investment imperatives. When farmland investments touch ground, place-based specifies such as policy, legal regimes, infrastructure, and the physical environment shape what imperatives are applicable (Ouma, Citation2014). Here, moral performance becomes again pivotal to achieve and maintain socio-political legitimacy within the territorial setting that farmland investments penetrate: the creation of jobs, tax incomes, but also the integration of smallholders can create this legitimacy (Li, Citation2015). These territorial-institutional settings at investment destination are, therefore, complementary to the financial sphere of investors and supporters in co-constituting the ground rules for farmland investments.

Ouma (Citation2014) argues in this vein, that a reading of financialisation ‘from above’ (the financial sphere of investments) should include – if not be replaced – by a perspective ‘from below’ (the place and space-based sensitivity of such investments). Only then, an overemphasis as seeing financialisation as explanatory for almost everything can be avoided (see also Christophers, Citation2015). To create sensibility for place and space-based implications, we adopt Pike & Pollard’s (Citation2010) two-fold framework on the economic geographies of financialisation.

2.1. Widening and deepening range of agents, relationships and sites

Pike & Pollard (Citation2010) raise that financialisation processes should be understood as inescapably rooted in their geographic context. Therefore, a scalar reading of financialisation can help identify what spaces are made, linked, and affected by a widening range of financial actors and practices. These spaces can be conceptualised as territorial – bounded – entities (e.g. nation-states, regions) and relational – unbounded – flows (e.g. capital circulation, trading networks).

Accordingly, we address the financialisation of farmland in relation to value chains as follows: In territorial terms, the financialisation of farmland links (i) the socio-institutional settings from which networks investors and intermediaries originate with (ii) the domestic setting at destination of a farmland investment (e.g. the corridor region). In relational terms, we differentiate between (iii) the investment chain as constituted between financial actors and farmland investment, and (iv) the terms of integration between farmland investment and smallholders (). With this approach to financialisation, we create the geographical sensibility necessary to disentangle the role of finance for corridor-making.

Table 1. Framework for the analysis of farmland investments and value chain integration of smallholders.

2.2. Tensions between territorial and relational spatialities

According to Pike & Pollard, the territorial and relational spatialities under which financialisation processes unfold and that they parallelly create can lead to tensions and discrepancies. Such tensions reveal the often uneven and contradictory everyday consequences of financialised spatialities. Therefore, we derive analytical themes from the four identified sub-types of spatialities (). For both territorial entities, the institutional setting (e.g. human rights regulations for investors, conditions to receive financial subsidies from public sources) of financial actors vis-à-vis the setting in the investment destination (e.g. agricultural policy, property regimes, production factors) are co-constitutive for investment imperatives. This differentiation serves to disentangle how and by whom financial as well as moral investment imperatives are driven and how they are affected under changing territorial conditions either at financial actors’ origins and/or destination of investment.

For the relational spatialities of investment and value chains, the same understanding of how investment imperatives are co-constituted can further explain how the investment chain (expressed by the flow of capital and its imperatives) relates to the structures and dynamics of operating large-scale farms and also integrating smallholders into value chains (expressed through the terms of integration). Ruptures and tensions can then become visible when these analytical categories shift.

This two-fold analytical framework of first differentiating the spatialities under which farmland investments occur, and then probing them for their tensions will guide our empirical analysis. We use the framework to show how farmland investments affected the integration of smallholders into value chains along SAGCOT.

3. Case study selection and methods

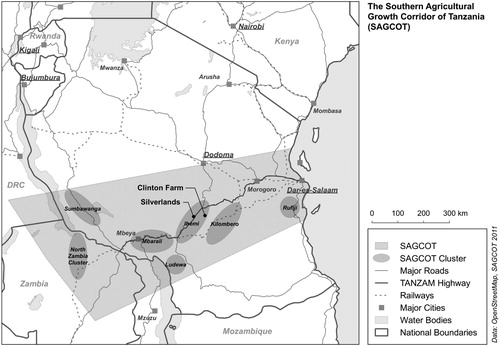

We draw from empirical work along the Tanzanian SAGCOT corridor and present two farmland investments that have materialised shortly after SAGCOT’s launch (). We chose these cases as they have been repetitively put forward as successes of SAGCOT. Both aligned their financial and operational models with SAGCOT’s blueprint from the onset and were integral to developing the prioritised value chains of soya and maize.

Our data consists of the following: (i) a review of academic and grey literature on SAGCOT and investment cases; (ii) 32 problem-centric interviews with project managers and employees, donor representatives, small- and large-scale farmers, and SAGCOT and government representatives; as well as (iii) five farm visits. Data on the case studies were collected during long-term research stays in late-2018 and mid-2019 by the first author.

A major limitation lays in the politicised nature of SAGCOT in general and both case studies in particular. To remain politically legitimate, SAGCOT stakeholders are careful to control the corridor’s public representation. Further, as Brüntrup et al. (Citation2018) line-out, especially farmland investments at financial or political risk often allow only limited empirical access to ‘their inside’. Accordingly, our long term research stays were crucial for contextualisation amid the shifting political economy of Tanzania and SAGCOT.

4. Results

The SAGCOT corridor was launched by a state-capital alliance of donors, multinational agri-businesses and the Tanzanian government in 2010 (Mbunda, Citation2016; Bergius et al., Citation2018). Covering an infrastructure axis, the corridor proposes several priority value chains, such as soya, beef, maize, and others, as favourable investment cases (). In a grand-modernist fashion aiming to ‘deliver rapid and sustainable agricultural growth’, SAGCOT’s (Citation2011:2) Investment Blueprint promotes investments into value chains particularly through commercial, large-scale farms (Sulle, Citation2020). The promotion of commercial farms as investable assets feeds into the goal to untap an ostensibly underexploited potential to exploit land for farming. Nevertheless, due to the ‘greenfield state of development’ (SAGCOT:19) more than commercial capital is required to overcome unfavourable economies of scale and scope for purely private investments. As a fix, the blending of private with public capital to kick-start a ‘virtuous agricultural growth cycle’ (SAGCOT:19) is put forward. Funders aiming at creating social impact and willing to abstain from immediate profits (donors, philanthropists, social impact investors) are hence targeted as early capital sources (de Cleene, Citation2014). Sensible to the need to legitimise the access to such funding, SAGCOT’s blueprint highlights further that ‘the most important requirement is that smallholder farmer and local community benefits are built into the project from the outset’ (42). For this, farmland investments should foster the integration of smallholders into value chains (de Cleene, Citation2014:38).

Contrary to blueprint goals, our and other research (e.g. Mbunda, Citation2016; Bergius et al., Citation2018; Brüntrup et al., Citation2018, Sulle, Citation2020) highlights however that 10 years after SAGCOT launch, implementation of the corridor is way behind schedule – if not under existential threat. With the legislative shift from president Kikwete to his successor Magufuli in 2015, a general turn towards industrialisation policies vis-à-vis the former focus on agriculture-led development has scrambled the Tanzanian economy. This scramble has since decreased SAGCOT’s relevance substantially. Domestically, declining support by the Tanzanian government was paired with worldwide accusations that SAGCOT facilitates land grabs (Bergius et al., Citation2018; Bluwstein et al., Citation2018). Today, the confidence in the corridor project among investors has clearly suffered and also the international donor community froze or withdrew substantial shares of initially committed funds (Sulle, Citation2020). Accordingly, the dynamic political economy of the SAGCOT territory is characterised by an early stage of widespread attention and massive investment commitments that was followed by a gradual withdrawal of support and today’s dawning failure of the whole project. This dynamic is important as it defines the territorial setting of both case studies.

4.1. Silverlands Tanzania

Silverlands Tanzania aggregates one of the largest farmland investments in the corridor. Part of the Tanzanian portfolio is a poultry farm that integrates smallholders into its value chain.

4.1.1. Investment chain and territorial origins of Silverlands Tanzania

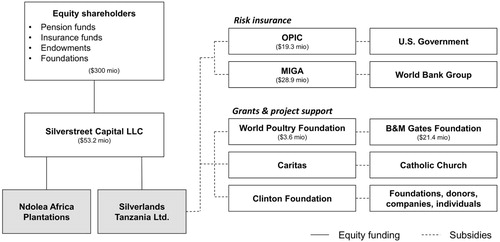

Silverlands Tanzania is entity of SilverStreet Capital, a UK-governed and Luxembourg-based private equity fund, that manages an investment portfolio worth $300 million. During fundraising in 2009, SilverStreet collected capital by private and institutional investors, such as European pension funds, insurance companies and development finance institutions (e.g. the Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC)). The fund operates farms in Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia. The Tanzanian investment of $49.7 million is split into Silverlands Ndolela (two farms totalling 2200 ha for cropping) and Silverlands Tanzania (673 ha farm for poultry). With $19.3 million and $28.9 million, respectively, the US development finance institutions Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) further back the portfolio against risks of expropriation, political violence, and fragile regulatory frameworks (OPIC, Citation2015). Moreover, donor and philanthropist projects support the Tanzanian investment. The World Poultry Foundation by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) allocated a $3.6 million grant to establish an extension network for poultry breeders. Caritas International and the Clinton Foundation ran smallholder-oriented programmes on soya cultivation ().

In total, Silverlands’ investment chain is far from being a straight-forward commercial investment. In territorial terms, the investor landscape is composed of funders and supporters with predominantly UK and US origin who indeed blend private with public capital. This blending explains a two-fold investment imperative for Silverlands’ operations.

On the one side, equity investors expect whopping profits between 20 and 25 percent annually for the 10-years investment cycle.Footnote2 At the end of the investment cycle sometime between 2021 and 2022, the fund will divest all assets.Footnote3 Hence, Silverlands’ investment imperative follows foremost the logic to develop, operate, and eventually liquidate all assets for profit.Footnote4 This imperative fits well with the subsidiary risk insurances provided by OPIC and MIGA as their subsidies underlie the eligibility criteria of facilitating US-based private capital to gain foothold in global South economies.

On the other side, however, particularly indirect support for the farm's development and operational costs through public capital (e.g. CDC, OPIC, MIGA), but also philanthropic activities (Caritas, BMGF), adds a moral imperative to the investment. This moral imperative is defined by different frameworks, such as the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation Performance Standards, or the CDC’s Modern Slavery Act. These frameworks define an overlapping and fuzzy set of sustainability standards and can be summarised as going beyond ‘avoiding harm’ as they aim not only to alleviate issues such as land grabbing, but at the creation of environmental and social benefits (e.g. OPIC, Citation2015).

In total, both, the territorial setting of originating funders and the relational structure of Silverlands' investment chain define not only the long-term operational logics of the farm (develop – operate – liquidate), but also a constant pressure to uphold legitimacy in form of a win-win narrative in front of its shareholders and supporters. To do the latter, Silverlands uses its poultry farm.

4.1.2. Silverlands approach of integrating smallholders into its value chain

Silverlands uses a hub out-grower model for its poultry farm as proposed in SAGCOT’s blueprint. Other than fully integrated poultry businesses that would have missed ‘a massive development opportunity for Tanzania’ (Silverstreet, Citation2018:23), the externalisation of upstream activities is communicated as creating social impact.

Generally, Silverlands’ poultry chain foremost relies on its on-farm operations: investments into sophisticated farm equipment allow the farm to produce about 170 000 heads of day-old chicken and 400 tons of feed weekly. Beyond-farm, Silverlands involves in arm’s length trading with smallholders to access raw materials for feed production. Since 2015, maize and soya purchases have increased from 4200 to 44 000 tonnes, thus making Silverlands a regional offtaker for about 8000 soya and 9500 maize farmers (SilverStreet, Citation2018). Pivotal for this are tight partnerships with donor or philanthropist projects. These smallholder-oriented projects create economies of scale when purchasing maize and soya as well as for disseminating new varieties and production technology necessary to match Silverlands’ raw material needs. At downstream side, Silverlands further raises the externalisation of breeding and retailing to local breeders as creating impact. Here, Silverlands – again with strong philanthropic support by the BMGF through the World Poultry Foundation – involves in extension activities to expand the Tanzanian value chain for poultry.Footnote5

4.1.3. Tensions in navigating financialised spatialities

Merging Silverlands’ moral with financial investment imperatives is messier than suggested at first glance. Indeed, as stated by the farm management, the navigation between relational and territorial tensions of the investment have substantial implications for everyday operation:

We have to balance between being a responsible investment and being profitable. For me, as a businessman, this was something totally new.Footnote6

It is difficult to quantify our impact, but it’s absolutely necessary to document it for our board of investors. Measuring our impact has become a part of our day-to-day business.Footnote7

Accordingly, everyday farm operations follow more than sole commercial reasoning. The mixed investment imperative translates into an omnipresent pressure to proof social impact.

Expressive for this pressure to proof social impact, and thus the creation of (moral) value, is especially the trading of soya for feed production. The quality of soya is decisive for processability and, according to farm management, it would be economically most feasible to bulk-import and store large volumes of soya at high quality and lower price from Zambian large-scale producers.Footnote8 Yet, Silverlands opts for nurturing a regional, smallholder-based value chain to create moral value in the form of regional trust and legitimacy and social impact hard facts directed towards shareholders (amount of smallholders integrated).Footnote9 Despite philanthropic support via smallholder-oriented projects, the sourcing of soya from smallholders comes eventually with higher costs and less quality vis-à-vis the Zambian alternative.

In this sense, the decision whether to buy from smallholders is less based on how profitable their integration might be according to factors such as firm capability (e.g. soya quality) or transaction costs (high for smallholder-produced soya), but merely on how much this benefits Silverlands’ regional and trans-regional moral performance. This moral performance is essential to harmonise the different spatialities under which Silverlands operates. Silverlands has benefitted from this harmonisation strategy through the SAGCOT initiative (e.g. SAGCOT lobbying to remove taxations on feed production) and vice versa become an affirmative model to it.Footnote10 Today, Silverlands is communicated as the ‘puller of SAGCOT’s soya value chain'Footnote11 and used as precedence case for how SAGCOT’s investment strategy might work elsewhere.

Against these successes of the Silverlands investment, the same translation of imperatives to operational level creates however also paradoxical tensions. First, whereas Silverlands’ poultry chain is used to showcase and capitalise on the social impact of SilverStreet’s Tanzanian portfolio, the much larger crop farms, where high-value activities such as export-oriented crop or seed re-production take place, are generously ignored with regard to where social impact practices are pursued. Creating social impact through the poultry farm seems to suffice to legitimise the otherwise exclusive counterparts of Silverlands’ Tanzanian portfolio (see SilverStreet, Citation2018). Even where smallholders are integrated (poultry farm), the extent of this integration is thin. As smallholder integration is limited to supplying raw materials, smallholders remain with activities where little value is captured and upgrading is unlikely. Both, the spatial and functional selectivity of where financial and moral value is created show therefore that Silverlands’ can leverage its self-conceptualising position to govern how, where, and to the favour of whom moral as well as financial value is created.

Second, the SilverStreet fund’s investment plan raises questions about the long-term prospect of smallholder integration. As a stated by the farm management:

Let me be clear: we are a private equity investment, so that means the ambition is to build a business and sell it on a future date. They [the investor board] might decide to sell everything, they might also decide to launch a second round of investment. We don’t know about their decision.Footnote12

This indicates that, regardless of how successfully smallholders can integrate into Silverlands’ operations, latest the liquidation of the fund’s assets will start a new round of investment and then reconfigure the investment imperatives at place. SilverStreet’s investment circle is more short-sighted than the 30-years SAGCOT plan or the long-term goals of donors to achieve some form of sustainable impact. Whereas the development costs of SilverStreet’s investment were heavily flanked by subsidiary funds (donors, philanthropists) and institutional backing (SAGCOT, Tanzanian government) along the assumption of mutual interests, it remains unaccounted how these interests might shift at date of divestment. Particularly the looming demise of SAGCOT and the widespread withdrawal of public and benevolent funding, questions whether moral imperatives can be upheld in such way that smallholder integration vis-à-vis the alternative of buying raw materials elsewhere remains profitable.

4.2. Clinton Development Farm

The Clinton Development Farm (CDF) established in close partnership with SAGCOT. Despite initially integrating smallholders as an offtaker, recent changes in the farm’s investment chain have fully reconfigured how CDF operates.

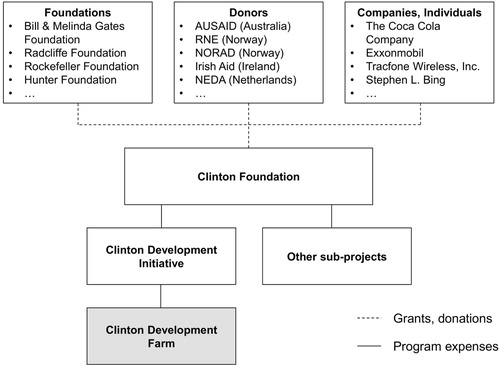

4.2.1. Investment chain and territorial origins of the Clinton Farm

In 2013, the Clinton Development Initiative (CDI), a subsidiary of the US-based Clinton Foundation, launched a farming project similar to Silverlands. The Clinton Foundation is an donation-based foundation that raises capital for in-house projects from governments, firms, individuals and other foundations mainly in the USFootnote13 (). Therefore, the foundation does not underlie a strict imperative of generating profits but uses the inflow of donations for covering operational costs. This funding model allows the foundation to be relatively flexible and independent from hard(er) international standards for measuring impact. The foundation summarises its impact obligation as follows:

At the end of the day of course, the most important piece of data is the number of lives saved, improved, and empowered – or as we like to say, the number of people who are now living better life stories.Footnote14

To achieve the benevolent but fuzzy aim of creating better life stories, the CDI long followed its house-made Anchor Farm Approach. The approach aimed at developing value chains for smallholders by establishing large-scale hub farms as offtaker and centre of innovation. Thus, although the farm’s investment chain is not shareholder-driven like Silverlands, the CDF aimed just as well at developing a commercial farm that could provide economies of scale for smallholders and operate profitable on the long run.

4.2.2. Clinton Farm’s approach of integrating smallholders into its value chain

Due to the similarity of the CDI’s Anchor Farm Approach (at that time already applied in Malawi and Rwanda) and SAGCOT’s hub farm model, the CDF affiliated with the SAGCOT initiative from the onset. Most illustratively, SAGCOT assisted the CDF to take-over the state-owned 1000-hectare through a 20 years lease agreement.Footnote15

With an initial investment of $5.0 million, particularly the commercial farm was equipped with agricultural machinery and silos for large-scale cultivation of maize and soya. Additionally, the CDI launched a programme for about 6000 smallholders to target the introduction of high-yielding farming practices and pool the marketing of crops. Here, the commercial farm occupied a three-fold function of creating economies of scale for distributing inputs, hosting agricultural trainings, and facilitating commodity trades with larger buyers such as Silverlands, Tanzania's National Food Reserve Agency, and processors from Northern Tanzania.Footnote16 Our interviews suggest that the CDF indeed positively impacted surrounding communities with this approach.Footnote17 In total, the first few years of the CDF describe a period in which the unprecedented inflow of philanthropic capital mobilised widespread excitement about the CDF. Although observed sceptically for the high operational costs which had to be covered by the foundation,Footnote18 smallholders scored higher yields and integrated more tightly into domestic value chains for maize and increasingly soya.

4.2.3. Tensions in navigating financialised spatialities

Despite the promising launch, CDF’s operations came to a sudden halt only four years later. When first visiting the farm in 2018, fallow plots and deserted infrastructure were all that was remaining. The operation of the farm was suddenly stopped in late-2018.

Although explanations for the shutdown are complex, two shifts were fundamental. Firstly, the shifting territorial setting in Tanzania forced the withdrawal from CDF:

With anchor farm, we were selling to big buyers. That means you have to go into business transactions. At this moment, it also means you are encroaching the purpose of being a non-profit organisation. […] That is why we had to stop anchor farm.Footnote19

Indeed, increased enforcement of tax collection and rigid auditing of non-profits went hand in hand with the declining relevance of SAGCOT under the new Tanzanian government (Sulle, Citation2020). With the re-regulation from ‘tax holidays’Footnote20 for foreign capital towards strict enforcement of tax collection, the territorial setting for commercial farming – even when listed as non-profit – had changed dramatically. Under these circumstances, the CDF’s operation somewhere between commercial and non-profit entity was no longer tolerated by the Tanzanian government.

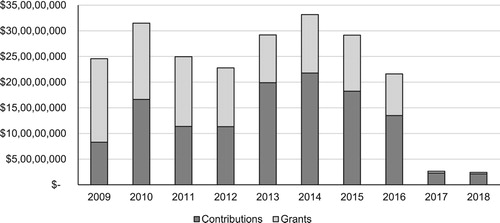

In US territory, the farm’s investment chain further experienced a blow due to US politics. With the defeat of Hillary Clinton in the presidential elections and far-right media house-driven conspiracy theories that accused the foundation of money laundering, the foundation’s ability to raise capital suffered dramatically. Whereas annual support long amounted to about $250 million, same support fell below $25 million in 2017 and has since not recovered ().

The shifting territorial conditions of both domestic and foreign origin have thus fuelled a breakdown of the legitimacy and capacity of CDF’s investment chain. As stated by a former CDF employee, this breakdown meant a sudden withdrawal from operating the farm:

Finally, they sent an email for what they call a global meeting. It was addressed to all staff members. […] In the meeting, they gave us a one week notice and everyone was dismissed.Footnote21

The CDF’s shutdown has since created a vacuum of information among formerly integrated smallholders. Interviewees highlighted that the CDF’s withdrawal lacked transparent information about the core farm’s withdrawal and what this would imply for smallholders.Footnote22 Whereas maize could still be sold via alternative markets, particularly the Silverlands-destined soya was now stock-piling at smallholders’ farms and eventually fed to cattle rather than commercially traded.

Despite the sudden withdrawal from the farm, the foundation has, however, not fully phased-out. In 2019, the CDI introduced their Community Agribusiness Approach. Today, smallholder cooperatives are promoted as an alternative mode to train farmers and achieve favourable economies of scale in staple crop value chains. Hence, the CDI follows a totally different approach of promoting the smallholder integration.

The CDF’s brief operational history shows how territorial dynamics within Tanzania (tax collection and regulatory enforcement) but also the US (political turmoil) could suddenly jeopardise the whole investment and its value chains. Both territorial dynamics explain the foundation’s sudden withdrawal from funding the core farm and the dramatic consequences for formerly integrated smallholders. The withdrawal highlights how suddenly the spatialities created and linked by financialisation processes can collapse. Similar to Silverlands, such collapse is not explained by how feasible smallholder integration is. Rather, it can be explained through the lens of finance and the dynamic territorial and relational spatialities along which it unfolds.

5. Discussion

How can we make sense of the two case studies? At first glance, both investments materialised with similar operational models. Apart from operating a commercial core farm, they integrated several thousands of smallholders and confirmed with SAGCOT’s approach of blending private and public investments into farmland. However, our financialisation perspective allows for a deeper understanding of the circumstances under which both investments touched ground. Whereas other research has addressed the farm(er)-based, socio-economic outcomes of similar farming arrangements in detail (Kirsten & Sartorius, Citation2002; Bellemare & Bloem, Citation2018), a financialisation perspective can add to addressing the mechanism of such outcomes. Under mixed investment imperatives, smallholder integration follows no longer economic reasoning at place (the farm). Rather, the ‘smallholder slot’ becomes a resource to navigate the complex imperatives to which investments need to comply. How feasible the actual practice of integrating smallholders is becomes secondary. It is secondary as integrating smallholders is not entirely motivated by directly capturing value between commercial farm and smallholders, but as it is essential for creating moral value that can be translated into hard cash elsewhere.

In early times of SAGCOT, farmland investments could easily translate moral value. As long as moral imperatives as co-constituted by investors, donors, and the SAGCOT framework were adhered to, direct and indirect capital flows supported the development and operation of both commercial farms. Hence, it was less relevant how smallholders were integrated, but primarily whether. The legitimatory and subsidiary gains from smallholder integration clearly outweighed the otherwise complicated operations and opportunity costs of nurturing smallholder integration. Such paradox outcomes can only be understood with a space-sensitive perspective on financialisation.

Moreover, this perspective adds to understanding why ruptures of financialised spatialities can imply sudden reconfigurations for whether, why, and with what consequences smallholder integration remains attractive. These tensions became most visible with the CDF’s withdrawal and they are looming to become relevant for Silverlands. Under ‘working’ conditions, when territorial and relational spatialities align, smallholders might indeed benefit from farmland investments. But what happens when tensions become ruptures? As Kaarhus (Citation2018:108) concludes on similar investments in the Mozambican Beira Corridor: ‘who remains with the risks, and who is left to pay the debts, becomes acute when some partners leave’. In this sense, it is debatable to what extent public and benevolent capital is sustainably invested to the favour of smallholders. Here, our approach can scrutinise the unevenly distributed and often neglected risks of farmland investments – even beyond farm.

In short, a financialisation perspective is more than an intellectual exercise of approaching the same matter from different epistemologies. Rather, such perspective can contribute to practically inform negotiations between investors, donors, philanthropists and local actors when they venture into similar arrangements.

6. Conclusion

We argued that a financialisation perspective is important to understand how development corridors materialise. It helps to acknowledge the most accentuated logic of contemporary corridor-making. This logic is about attracting flows of global finance and channelling them into the development of value chains. Hence, rather than providing just roads, corridors demarcate territory and suggest assets to be incorporated into flows of global finance. These flows originate, on the one side, from benevolent and developmental aims among the international development community and, on the other side, from the pressure to establish alternative asset classes among global capital.

Our empirical work raises how SAGCOT’s design served to attract and blend both flows of finance. SAGCOT functions as a territorial tool that ultimately channels blended finance into farmland. The common denominator for such controversial blending can be found beyond farm; namely in the integration of smallholders. Smallholder integration has become a legitimatory practice for corridor-making in general, and for farmland investments in particular.

Whether, why, and with what consequences smallholders integration occurs is tightly related to the imperatives under which farmland investments unfold. Under mixed investment imperatives somewhere between benevolent social impact creation and the generation of shareholder value, smallholder integration is no longer explained single-handedly by transaction cost theory as suggested by conventional value chain literature. Mixed investment imperatives obfuscate the mechanisms of whether and at what terms commercial farms opt for integrating smallholders. Here, smallholder integration is no longer solely explained by the value created between commercial farm and smallholders. Rather, smallholder integration is rendered as a resource to capture (more) value elsewhere. This elsewhere is reflected by the extent to which moral value created by smallholder integration is exchangeable into financial value at different times and spaces (e.g. global fund raising and subsidies before investment, local subsidiary projects or institutional support after investment).

When value is no longer necessarily captured through mutually beneficial and sustainable chain arrangements, but by leveraging the number of ‘smallholders integrated’, the implications of smallholder integration require scrutiny. Although smallholders might indeed capture some of the initial gains of finance attracted into corridor territory, the sustainability of such arrangements cannot be taken for granted. Ruptures in territorial terms (originating from funders and/or the investment destination) can abruptly scramble the relational spatialities (investment chain and value chain) that allow to translate moral value created through smallholder integration into financial value for investors. When ruptures occur, the integration of smallholders can then quickly lose all its attractiveness.

How and to whose favour corridors target global flows of finance requires therefore careful consideration. Against calls to fast-track corridor-making, the question how to alleviate and distribute the risks along financialising value chains should not be marginalised. Planning for failures, not only for investors, but especially also smallholders, can help aggravate the tensions and unsustainable outcomes that corridors might otherwise produce.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 From here on ‘smallholders’.

2 Silverlands #4.

3 Silverlands #1.

4 Silverlands #4.

5 Silverlands #2.

6 Silverlands #2.

7 Silverlands #4.

8 NGO #2, Silverlands #2; 3.

9 CDF #3.

10 Smallholder #1; 2; commercial farmer #2; NGO #1; SAGCOT #1.

11 SAGCOT #1.

12 Silverlands #4.

13 For an overview see: https://www.clintonfoundation.org/contributors.

14 Annual Report 2013–2014 (https://www.clintonfoundation.org/about/annual-financial-reports).

15 CDF #4, SAGCOT #1.

16 CDF #4.

17 CDF #1; 4, NGO #1, commercial farmer #2, smallholder #1; 3, government representative #1; 2.

18 Commercial farmer #1; 2.

19 CDF #3.

20 CDF #4.

21 CDF #4.

22 CDF #4, smallholder #3; 4.

References

- Bargawi, HK & Newman, SA, 2017. From futures markets to the farm gate: A study of price formation along Tanzania’s coffee commodity chain. Economic Geography 93(2), 162–84. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2016.1204894

- Bellemare, MF & Bloem, JR, 2018. Does contract farming improve welfare? A review. World Development 112, 259–71. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.018

- Bergius, M, Benjaminsen, TA & Widgren, M, 2018. Green economy, Scandinavian investments and agricultural modernization in Tanzania. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45(4), 825–52. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1260554

- Bluwstein, J, Lund, JF, Askew, K, Stein, H, Noe, C, Odgaard, R, Maganga, F & Engström, L, 2018. Between dependence and deprivation: The interlocking nature of land alienation in Tanzania. Journal of Agrarian Change 18(4), 806–30. doi: 10.1111/joac.12271

- Borras, S, Mills, E, Seufert, P, Backes, S, Fyfe, D, Herre, R & Michéle, L, 2020. Transnational land investment web: Land grabs, TNCs, and the challenge of global governance. Globalizations 17(4), 608–28.

- Brüntrup, M, Schwarz, F, Absmayr, T, Dylla, J, Eckhard, F, Remke, K & Sternisko, K, 2018. Nucleus-outgrower schemes as an alternative to traditional smallholder agriculture in Tanzania – strengths, weaknesses and policy requirements. Food Security 10(4), 807–26. doi: 10.1007/s12571-018-0797-0

- Christophers, B, 2015. The limits to financialization. Dialogues in Human Geography 5(2), 183–200. doi: 10.1177/2043820615588153

- Clapp, J, 2014. Financialization, distance and global food politics. The Journal of Peasant Studies 41(5), 797–814. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.875536

- Dannenberg, P, Diez, JR & Schiller, D, 2018. Spaces for integration or a divide? New-generation growth corridors and their integration in global value chains in the global South. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 62(2), 135–51. doi: 10.1515/zfw-2017-0034

- de Cleene, S, 2014. Agricultural growth corridors – unlocking rural potential, catalyzing economic development. In D Köhn (Ed.), Finance for food, 67–87. Springer, Berlin.

- Ducastel, A & Anseeuw, W, 2017. Agriculture as an asset class: reshaping the South African farming sector. Agriculture and Human Values 34(1), 199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10460-016-9683-6

- Epstein, GA, 2005. Financialization and the world economy. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

- Fairbairn, M, 2014. ‘Like gold with yield’: Evolving intersections between farmland and finance. Journal of Peasant Studies 41(5), 777–95. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.873977

- Fuchs, D, Meyer-Eppler, R & Hamenstädt, U, 2013. Food for thought: The politics of financialization in the agrifood system. Competition & Change 17(3), 219–33. doi: 10.1179/1024529413Z.00000000034

- Kaarhus, R, 2018. Land, investments and public-private partnerships: What happened to the Beira agricultural growth corridor in Mozambique? The Journal of Modern African Studies 56(1), 87–112. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X17000489

- Kirsten, J & Sartorius, K, 2002. Linking agribusiness and small-scale farmers in developing countries: Is there a new role for contract farming? Development Southern Africa 19(4), 503–29. doi: 10.1080/0376835022000019428

- Kish, Z & Fairbairn, M, 2018. Investing for profit, investing for impact: Moral performances in agricultural investment projects. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50(3), 569–88. doi: 10.1177/0308518X17738253

- Li, T, 2015. Transnational farmland investment: A risky business. Journal of Agrarian Change 15(4), 560–8. doi: 10.1111/joac.12109

- Martin, SJ & Clapp, J, 2015. Finance for agriculture or agriculture for finance? Journal of Agrarian Change 15(4), 549–59. doi: 10.1111/joac.12110

- Mawdsley, E, 2016. Development geography II: Financialization. Progress in Human Geography 42(2), 264–74. doi: 10.1177/0309132516678747

- Mbunda, R, 2016. The developmental state and food sovereignty in Tanzania. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 5(2–3), 265–91.

- McMichael, P, 2012. The land grab and corporate food regime restructuring. The Journal of Peasant Studies 39(3–4), 681–701. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.661369

- Moseley, WG, 2016. The new green revolution for Africa: A political ecology critique. The Brown Journal of World Affairs 23, 177–90.

- Newman, SA, 2009. Financialization and changes in the social relations along commodity chains: The case of coffee. Review of Radical Political Economics 41(4), 539–59. doi: 10.1177/0486613409341454

- Ouma, S, 2014. Situating global finance in the land rush debate: A critical review. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 57, 162–6.

- Ouma, S, 2016. From financialization to operations of capital: Historicizing and disentangling the finance – farmland-nexus. Geoforum 72, 82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.02.003

- Ouma, S, 2020. This can(t) be an asset class: The world of money management, ‘society’, and the contested morality of farmland investments. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52(1), 66–87. doi: 10.1177/0308518X18790051

- OPIC, 2015. Silverlands Tanzania limited – public notice. https://www.opic.gov/sites/default/files/files/silverlands-info-summary.pdf Accessed 25 June 2019.

- Pedersen, RH & Buur, L, 2016. Beyond land grabbing. Old morals and new perspectives on contemporary investments. Geoforum 72, 77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.03.013

- Pike, A & Pollard, J, 2010. Economic geographies of financialization. Economic Geography 86(1), 29–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01057.x

- Purcell, TF, 2018. ‘Hot chocolate’: Financialized global value chains and cocoa production in Ecuador. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45(5–6), 904–26. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1446000

- Richey, LA & Ponte, S, 2014. New actors and alliances in development. Third World Quarterly 35(1), 1–21. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2014.868979

- SAGCOT, 2011. Southern agricultural growth corridor of Tanzania – investment blueprint.

- Schindler, S & Kanai, JM, 2019. Getting the territory right: Infrastructure-led development and the re-emergence of spatial planning strategies. Regional Studies, 1–12.

- Silverstreet Capital, 2018. Annual impact and ESG report – the Silverlands funds. https://www.silverstreetcapital.com/positive-social-impact/annual-esg-report-2018 Accessed 25 June 2019.

- Smalley, R, 2017. Agricultural growth corridors on the eastern seaboard of Africa: An overview. APRA Working Papers, 1.

- Staritz, C, Newman, S, Tröster, B & Plank, L, 2018. Financialization and global commodity chains: Distributional implications for cotton in Sub-Saharan Africa. Development and Change 49(3), 815–42. doi: 10.1111/dech.12401

- Sulle, E, 2020. Bureaucrats, investors and smallholders: Contesting land rights and agro-commercialisation in the Southern agricultural growth corridor of Tanzania. Journal of Eastern African Studies 14(2), 332–53. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2020.1743093

- Sulle, E & Hall, R, 2013. Reframing the new alliance agenda: A critical assessment based on insights from Tanzania. Policy brief – future agricultures (56).

- White, B, Borras, SM, Hall, R, Scoones, I & Wolford, W, 2012. The new enclosures: Critical perspectives on corporate land deals. The Journal of Peasant Studies 39(3–4), 619–47. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.691879