?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Despite the rapid economic growth recorded since the 1990s, inequality, poverty and unemployment levels remain high in most African countries. As such, achieving socio-economic goals has been the major focus of policymakers. The objective of this study is to examine the effect of financial inclusion on human development in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Access to and usage of financial services may encourage business start-ups, allow individuals to invest in health and education, manage risk and lessen the burden of financial shocks, and therefore, impact positively on human development. The study employs the panel data approach and utilises the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) technique. The results show that financial inclusion has a positive effect on human development. Therefore, it is recommended that policymakers implement measures that reduce the costs of access to and usage of financial services, such as investments in infrastructure, and raise awareness of the available financial services.

1. Introduction

Achieving the socio-economic goals of reducing poverty, inequality, and unemployment has been the major focus of African countries. In Africa, despite the rapid economic growth recorded since the 1990s, inequality, poverty and unemployment levels remain high (African Development Bank, Citation2018). Although poverty rates have declined since the 1990s, the number of poor people has increased, while inequality measured by the GINI index has risen. The high unemployment rates may be attributed to low levels of human development caused by a lack of access to quality education and health facilities, which in turn has rendered a large part of the population unemployable (African Development Bank, Citation2018).

The United Nations adopted developmental goals designed to ensure prosperity for individuals and the planet in 2015 (UNSGSA et al., Citation2018). The targets, 17 in total, are referred to as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs incorporate a wide variety of factors including environmental, socio-economic, gender equality and education, amongst others. Financial inclusion has been regarded as a means of achieving seven of the 17 SDGs, thus policy measures must be put in place to ensure its effectiveness in African countries (Klapper et al., Citation2016).

Financial inclusion, defined as the broadening of access to and usage of financial services, may enable African countries to achieve their socio-economic goals (Klapper et al., Citation2016). Access to financial services is captured by the availability of automated teller machines (ATMs) and the number of bank branches, which only represents the likelihood of usage (Cámara & Tuesta, Citation2014). Usage of financial services is measured by the number of people with loan, deposit and savings accounts in formal financial institutions. Access to and usage of financial services may allow individuals to invest in health and education, manage risk and lessen the burden of financial shocks, thus impacting positively on human development (United Nations Global Compact & KPMG, Citation2015). Furthermore, financial inclusion may promote smooth transfer of funds thus easing the flow of remittances between countries (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., Citation2018).

Access to and usage of financial services has improved over the last decade (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., Citation2018). However, as reported by Klapper et al. (Citation2016), a large part of the world population still has no access to formal financial services. In some developing/emerging economies, such as China, Kenya, India and Thailand, over 80% of the population has access to a financial account and this has contributed to improvements in human development (Klapper et al., Citation2016).

It is against this backdrop that this study examines the effect of financial inclusion on human development in selected countries in SSA using panel data analysis. The study’s contribution to literature is threefold. First, a number of existing empirical studies employed correlation analysis which is non-parametric and does not reveal the direction of causality between financial inclusion and human development (see Gupta et al., Citation2014; Nanda & Kaur, Citation2016; Raichoudhury, Citation2016). The study employs the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM) technique as the number of cross-sectional units is larger than the available time periods. This technique is parametric in nature and caters for endogeneity in variables. Second, some studies constructed indices of financial inclusion, which, although plausible due to the correlation between the financial inclusion indicators, does not show the effect of individual indicators on human development. Employing individual indicators of financial inclusion shows the effect of both usage and availability of financial services on human development, which is crucial for policy purposes. The human development indicator selected is the Human Development Index (HDI). Third, there is scant empirical evidence on the effect of financial inclusion on human development in African countries. Most studies are centred on the impact of financial inclusion or financial development on economic growth, which is not reflective of the achievement of socio-economic goals.

The study is structured as follows: section one introduces the study, section two provides a brief overview of financial inclusion and human development in SSA, section three surveys the existing literature, section four outlines the methodology and data used in the analysis, section five discusses the results of the empirical analysis and, lastly, section six concludes the study.

2. Overview of financial inclusion and human development in Sub-Saharan Africa

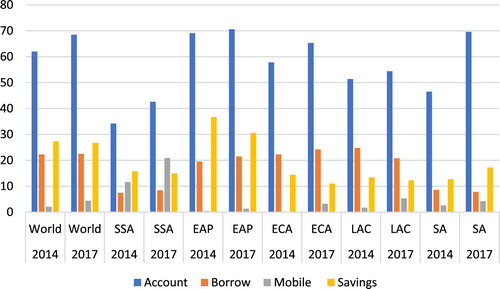

This section provides an overview of financial inclusion and human development in SSA. More recent data from the World Bank’s Findex report shown in indicates that there has been an improvement in financial inclusion in SSA countries. The region, however, still lags behind others in most of the financial inclusion indicators (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., Citation2018). The only exception is the usage of mobile money services, in which Africa is the leading region in the world; 20.9% of the adults in the labour force reported that they had used a mobile money account to conduct financial transactions in 2017, up from 11.6% in 2014.

Figure 1. Regional comparison of financial inclusion. Source: Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (Citation2018).

Notes: SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa, EAP = East Asia and Pacific, ECA = Eastern Europe and Central Asia, LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean, SA = South Asia.

The East Africa region, comprising countries such as Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, shows the highest levels of mobile money usage in Africa. According to the IMF’s Financial Access Survey (FAS), countries such as Ghana, Rwanda, Madagascar, Mozambique and Guinea have recently recorded significant growth in mobile money usage (IMF, Citation2018).

Human development is defined as the expansion of alternatives available to individuals as well as the opportunities that allow them to live their lives to the fullest (AfDB et al., Citation2013). The African continent has a history of low levels of human development despite the available natural resources. This view is supported by Fosu and Mwabu (Citation2010), who found that African countries continue to lag behind other regions of the world in human development. Human development is often measured by variables such as health, levels of education (human capital) and standards of living. In 1990, the United Nations developed the Human Development Index (HDI) as a tool to measure human development. The index comprises variables such as health (life expectancy), education (mean years and expected years of schooling) and standard of living (Gross National Income per capita) (UNDP, Citation2018). The index permits comparisons between countries to track progress made by each country or country group.

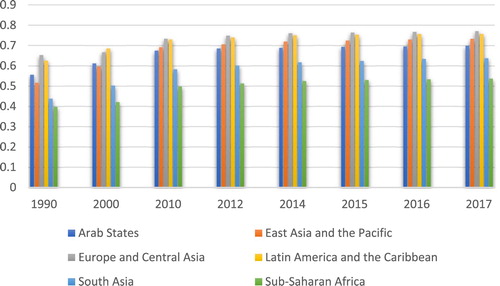

According to recent data from UNDP (Citation2018), all regions of the world recorded improvements in human development as shown by higher HDI values. However, SSA recorded an average value of 0.537 in 2017, which is the lowest amongst the major regions. The SSA region recorded declines in human development in the early 1990s due to wars and the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which resulted in a substantial decrease in life expectancy. During the period from 2000 to 2010, SSA recorded the fastest growth in HDI in the world; however, the growth rate has been sluggish since 2010.

The African region is home to the lowest ranked countries in terms of HDI, namely, Burundi, Chad, South Sudan, Central African Republic and Niger (UNDP, Citation2018). The highest ranked countries in Africa are Seychelles, Mauritius, Algeria, Tunisia, Botswana, Libya and Gabon. These countries achieved high human development levels, above 0.7, in 2017. shows HDI comparisons for the different regions. Despite improvements in human development in SSA, the region lags behind other regions. As such, the implementation of policies that enhance human development is crucial for further advances.

Figure 2. Regional HDI comparisons. Source: UNDP (Citation2018).

3. Literature review

This section provides a brief overview of the existing theoretical and empirical literature regarding the relationship between financial inclusion and human development.

3.1. Theoretical literature

The origins of the human development literature can be traced back to Aristotle, who argued that policymakers ought to have a clear understanding of the needs of individuals in order to enhance standards of living (Kuriakose & Iyer, Citation2015). Satisfaction of individual preferences requires an array of choices that an individual may act upon. As such, human development may be promoted by increasing the choices available to individuals. In line with Aristotle’s view, Adam Smith proposed an approach for enhancing human development by nurturing human abilities (Skousen, Citation2001). Prior to Smith’s views, real wages and standards of living of the working class were low and stagnant, and it was against this backdrop that Smith argued for economic freedom or liberty, which he believed was instrumental in promoting human capabilities.

Human capabilities, freedom and development were advanced in the nineteenth century by the utilitarian advocates such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill (Skousen, Citation2001). Utilitarianism is the view that an action is ‘good’ if it maximises individual welfare or well-being, which is measured by happiness (hedonistic theories) and satisfaction of preferences (Hausman & McPherson, Citation2006; Eggleston, Citation2012). Bentham advocated for legislative reform that would result in the greatest happiness for the largest number of individuals while Mill was of the view that personal liberty and human individuality are instrumental in promoting individual well-being.

The theory of the capability approach to human development was further advanced by Amartya Sen (Citation1987, Citation1992) and Nussbaum (Citation2000, Citation2001). Sen argued that the well-being of individuals is determined by their capabilities and functionings. Capabilities can be defined as personal attributes as well as a political, social and economic environment that promotes individual freedom, while functionings are individual experiences influenced by capabilities (Kuriakose & Iyer, Citation2015). As such, Sen (Citation1992) advocated for policy to be channelled towards capabilities that are the determinants of functionings. Nussbaum (Citation2000) went a step further and defined a set of capabilities that should be the target of policy (Hausman & McPherson, Citation2006); these included health, integrity, property rights and affiliation, amongst others.

In line with the above theories regarding human capabilities, the United Nations introduced the human development approach through the UNDP in 1990 (Kuri & Laha, Citation2011). The approach was advanced by Mahbub ul Haq, who used the HDI as an alternative measure for economic progress and development. While the UNDP (Citation2018) defines human development as the process of enlarging people’s choices to promote a long and healthy life, quality education, higher standards of living and political freedom, other aspects such as inequality, poverty and gender equality are also considered. As such, the economic development paradigm has shifted from income led-growth to human development and further to individual capabilities.

Literature on human development in Africa can be traced back to Claude Ake in the 1990s, who defined development as a process by which individuals evolve through their own actions in order to attain higher civilisation levels (Gumede, Citation2017). According to Cheru (Citation2009), development in African countries post the colonial era has lacked inclusiveness. This can be attributed to a developmental approach modelled around that of the colonial period, which limited people’s choices. Furthermore, Ake (Citation1981) argued that leadership failures in African countries have contributed significantly to the slow pace of development. This assertion is supported by de la Escosura (Citation2013), who suggested that human development advancement in Africa since the mid-twentieth century is positively linked to coastal and resource-rich countries and negatively to political economic distortions. Gumede (Citation2017) is of the view that social policies should be enacted to promote inclusive development in African countries.

The developmental approach required for African countries is one that promotes human capabilities. According to Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (Citation2017), financial inclusion may be instrumental in promoting economic growth and human development. The finance–economic development nexus can be traced back to Schumpeter (Citation1912) and Levine (Citation1997), who outlined the role of the financial sector in promoting innovation and production. The financial sector, through its effect on the pooling of savings, capital allocation and facilitation of trading, exerts a positive impact on economic growth and development. This notion is further supported by Greenwood Jovanovic (Citation1990), Bencivenga and Smith (Citation1991) and Saint-Paul (Citation1992).

The financial sector promotes human development through several channels. Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (Citation2018) are of the view that access to financial services supports the development of human capital, which is a major component of human development. Access to savings accounts and credit encourages investments in health and education, thus enhancing human development. Gupta et al. (Citation2014) suggested that financial inclusion provides opportunities for poverty alleviation as well as social and economic development by providing access to affordable financial services amongst the low-income and vulnerable groups within a society. A well-functioning financial system is crucial for channelling funds to their most productive uses and mitigating risks associated with loss of income, thus boosting human development, improving opportunities and income distribution, and reducing poverty (Allen et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, by promoting equal opportunities to access financial services, financial inclusion fosters economic integration of socially excluded individuals (Voica, Citation2017). Therefore, by ensuring ease of access to, availability and usage of the formal financial services for all individuals in an economy, financial inclusion is an important aspect of human development.

3.2. Empirical literature

In exploring the relationship between financial inclusion and human development, correlation analysis has been widely used (see Kuri & Laha, Citation2011; Sarma & Pais, Citation2011; Gupta et al., Citation2014; Nanda & Kaur, Citation2016; Raichoudhury, Citation2016; Dutta & Singh, Citation2019).

Nanda and Kaur (Citation2016) used the HDI as well as a modified HDI that captures financial availability and access and found a positive association between financial inclusion and human development in 68 countries. Raichoudhury (Citation2016) utilised an index of financial inclusion and also reported a positive correlation between financial inclusion and human development in a cross-country study. Kuri and Laha (Citation2011) and Gupta et al. (Citation2014) constructed financial inclusion indices using variables that capture penetration, availability and usage of banking services and concluded that there is positive correlation between financial inclusion and human development in Indian states. Similarly, Sarma and Pais (Citation2011) and Dutta and Singh (Citation2019) also constructed financial inclusion indices for developing and developed countries and found a positive association between financial inclusion and human development.

There is a strand of literature that promotes the efficacy of mobile money in enhancing financial access and human development in African countries. Asongu (Citation2013) reported that mobile money may be a crucial channel through which the informal sector may be able to access finance. Asongu and Nwachukwu (Citation2016) concluded that governance and institutions complement mobile money in promoting inclusive human development in SSA. Gosavi (Citation2018) suggested that mobile money mitigates the problem of lack of access and enhances productivity for businesses, which supports the findings of Asongu (Citation2013).

Some studies have noted the challenges that are encountered in ensuring availability of and access to financial services which may hinder human development. Arora (Citation2012) studied the relationship between financial development and human capital in developing Asia. She noted that a number of studies do not take into account the fact that low human development and high illiteracy levels in developing economies may prevent a large section of the population from benefitting from financial inclusion efforts because of low awareness and comprehension of the financial services available. Bagli and Dutta (Citation2012) suggested that the major causes of financial exclusion are geographical distance from a bank, financial illiteracy, gender inequality, lack of income and collateral assets and lack of identity documents amongst disadvantaged individuals. On the other hand, staff shortages, high transaction costs and economic viability of branches are common problems encountered by financial institutions in extending financial services to disadvantaged areas.

Tita and Aziakpono (Citation2017) examined the welfare enhancing effect of financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan African countries using a cross-sectional framework. Income inequality was employed as a proxy for welfare. The findings indicated that financial inclusion increases income inequality, suggesting that the availability of financial services may not lead to usage. Furthermore, first-time account users may experience difficulties in accessing loans due to moral hazard and information asymmetries. However, Tchamyou and Asongu (Citation2017) suggest that information sharing through credit bureaus and public credit registries may promote finance access in African countries.

4. Data and methodology

This section discusses the properties of the data as well as the methodology. The financial inclusion indicators are sourced from the IMF’s financial access survey and the human development proxies were gathered from the United Nations. All the control variables were obtained from the World Bank’s (Citation2019) world development indicators except institutional quality (property rights), which is sourced from the Heritage Foundation (Citation1995). The study covered the period from 2004 to 2017.

4.1. Methodology

The panel data approach is selected for the empirical analysis. The approach is suitable for the analysis due to its superiority over time-series and cross-sectional methods. Problems such as multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity are minimised using the panel data approach (Hsiao, Citation2003; Baltagi, Citation2005). Furthermore, due to the limited number of time-series observations in the study (14 years), the panel approach is more suitable for the analysis as it allows for more degrees of freedom, which improves the precision of estimations.

The empirical model of the analysis is specified as follows:(1)

(1) where HD represents the measures of human development, FIN is the indicators of financial inclusion, WAT is the percentage of the population with access to basic drinking water services, INT is the number of individuals using the internet as a percentage of the population, HEA is public health expenditure as a percentage of GDP, UNE is the unemployment rate, FDI is foreign direct investments, INS is the level of institutional quality and

is the error term. The

and

subscripts indicate the time-series and cross-sectional components of the data.

Human development is captured by the HDI constructed by UNDP. The index is created using components such as health, educational attainment and gross national income and is widely used as a measure of human development (see Binder & Georgiadis, Citation2011; Shuaibu & Oladayo, Citation2016; Rastogi & Gaikwad, Citation2017; Arisman, Citation2018). The individual components of the HDI will be regressed on the indicators of financial inclusion for policy analysis.

Financial inclusion is proxied by six indicators that capture the access to and usage of financial services. These measures are:

ATMs per 1000 people (ATMS)

Borrowers at commercial banks per 1000 adults (BORROW)

Number of commercial bank branches per 1000 km (BRANCH)

Deposit accounts with commercial banks per 1000 adults (DEPOSIT)

Outstanding deposits with financial institutions (DEPS)

Loan accounts at commercial banks per 1000 adults (LOAN)

The authors would have preferred to include mobile money as one of the measures of financial inclusion. However, time-series data on mobile money is not adequate for empirical analysis. Studies that have included mobile money in African studies have utilised survey data in cross-sectional studies (see Asongu, Citation2013; Fanta et al., Citation2016). The six measures of financial inclusion mentioned above will be used in separate regression models. This is done to ensure the robustness of the results and to avoid the consequences of severe collinearity in the indicators of financial inclusion.

Access to basic drinking water and internet usage represents the level of infrastructural development, which is expected to have a positive effect on human development and welfare (Shuaibu & Oladayo, Citation2016). Access to drinking water is a measure of the quality of physical infrastructure (National Research Council, Citation1996). Internet usage is an indication of the development of digital infrastructure, which promotes human development (see Lee et al., Citation2017; Ejemeyovwi et al., Citation2019). The public health expenditures variable is expected to be positively related to human development. Government expenditure on health has a direct effect on the health component of the index (life expectancy) and promotes educational attainment and income (Agarwal, Citation2015). Unemployment is a hindrance to human development and welfare as it reduces private expenditure on education and health. Furthermore, employment as a measure of social inclusion and quality of life is a crucial determinant of sustainable human development (Taner et al., Citation2011).

FDI represents the level of openness in an economy, which promotes human development through job creation, skills development and the diffusion of technology (Rastogi & Gaikwad, Citation2017). Institutional quality is expected to have a positive effect on human development (Binder & Georgiadis, Citation2011). Institutions that uphold property rights encourage innovation and investments in human and physical capital from both domestic and foreign sources, which in turn boosts incomes and promotes job creation (Acemoglu et al., Citation2014).

EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) can be estimated using various panel data methods. These techniques include the pooled OLS, fixed effects (FE), random effects (RE), cointegration models such as the pooled mean group (PMG) and mean group (MG) estimators, instrumental variable models such as the generalised methods of moments (GMM) and two-stage least squares (TSLS). The pooled OLS model does not cater for the heterogeneity across panels and, therefore, is not an ideal technique (Hill et al., Citation2012). The heterogeneity is shifted to the error term, which may result in correlation between the error term and the regressor, which violates one of the assumptions of the classical linear regression model and as such the estimated coefficients would be biased and inconsistent.

The fixed effects model caters for heterogeneity in the cross-sectional units; however, the fixed-effect within-group estimator may result in biased estimates as long-run effects are eliminated (Gujarati & Porter, Citation2009). The random effects model is similar to the fixed effects model; however, the technique assumes that the individual effects are random rather than fixed (Hill et al., Citation2012; Bell & Jones, Citation2015). Cointegration models such as the PMG and MG estimators are used to estimate the long-run relationship between variables. Both techniques are autoregressive in nature and thus utilise lags of the variables (Pesaran et al., Citation1999). As such, these models require panels with a large number of time-series observations.

Instrumental variable models are proposed to cater for endogeneity present in regression models (Baltagi, Citation2005). Endogeneity in this study is introduced by the interrelationships between the variables. The techniques employ proxy variables correlated with a particular regressor but orthogonal to the error term (Wooldridge, Citation2002). The GMM model is the preferred technique because it may be used in the presence of first-order serial correlation and heteroscedasticity, which are common in empirical models (Baum et al., Citation2003). Arellano and Bond (Citation1991), Arellano and Bover (Citation1995) and Blundell and Bond (Citation1998) developed GMM estimation techniques. The GMM estimators are ideal for studies with a small number of time periods and a large number of cross-sectional units (Roodman, Citation2009). The GMM technique is thus ideal for this study as the number of cross-sectional units is greater than the time-series observations. To ensure the validity of the estimated coefficients, diagnostic tests are performed on the GMM models. The Arellano and Bond (Citation1991) test for second-order serial correlation is employed due to the use of lagged regressors as instruments. The instruments selected should meet the orthogonality requirement and, as such, the Hansen (Citation1982) as well as the Difference-in-Hansen tests are employed to test for the validity of the instruments.

5. Empirical results

The empirical results are presented in this section. Each table with the empirical results includes the coefficients at the top followed by the diagnostic tests towards the bottom. The models above pass the diagnostic tests and, therefore, the analysis may proceed to the interpretation of the coefficients. The GMM models were estimated using Roodman’s (Citation2009) xtabond2 command in Stata. In , each proxy of financial inclusion is regressed on the human development index.

Table 1. Empirical results, dependent variable: HDI.

The financial inclusion measures have a positive effect on the HDI, with the exception of outstanding deposits at commercial banks. This finding supports the hypothesis that financial inclusion may provide a means of solving some of the developmental goals of the Sub-Saharan African countries. Access to financial inclusion captured by the number of ATMs and the number of bank branches, especially in remote areas, may encourage the use of financial services for private health and education expenditure. The results support the findings of Nanda and Kaur (Citation2016), Raichoudhury (Citation2016), Gupta et al. (Citation2014), Sarma and Pais (Citation2011) and Dutta and Singh (Citation2019), who reported a positive association between financial inclusion and human development. The finding implies that African countries ought to enhance access to and usage of financial services as a means of achieving the socio-economic goals of poverty reduction, equality and lowering unemployment levels. Access to loans may promote expenditure in areas that improve human development, such as education and healthcare. Furthermore, loans may be used for business start-ups, which lower unemployment and poverty levels. The socio-economic goals are linked to human development to a large extent. High poverty and unemployment levels could be the result of low levels of human development, which have prevented a substantial part of the population from responding to higher demand for labour during periods of economic growth.

Evidence shows that infrastructural improvements represented by access to basic drinking water and internet usage have a positive impact on human development. This supports a priori expectations as infrastructure promotes productivity and quality of life (Mohanty et al., Citation2016). Unemployment has an insignificant effect on human development to a large extent while public health expenditure has a negative coefficient in a majority of the models, which contradicts a priori expectations. The negative coefficient of public health expenditures may be indicative of inefficiencies in government spending which has been a problem for a number of African economies (Novignon, Citation2015). Institutional quality has a positive and significant effect on human development in only half of the models. A possible reason could be the low levels of institutional quality associated with African countries, hence the lack of robustness in the finding. There is also evidence of lack of robustness with regards to the effect of FDI inflows on human development.

In the second part of the empirical analysis, a regression of the financial inclusion indicators on the components that constitute the HDI is conducted. The purpose of such an analysis is to show the effect of financial inclusion on the different indicators of human development, which is crucial for policy formulation. As shown in , financial inclusion is positively related to life expectancy, which is a measure of health. However, the coefficients of BORROW and DEPs are insignificant at the 5% level.

Table 2. Empirical results, dependent variable: LIFE.

Access to financial services may enable households to save for relatively smaller health expenses (Morgan & Churchill, Citation2018). Since outstanding deposits represent funds that have been recorded but not received, it is not surprising that the variable has an insignificant effect on health. The results support the findings of Masiyandima et al. (Citation2017), who reported that financial inclusion had a positive effect on health in Zimbabwe. Furthermore, Gyasi et al. (Citation2019) found that financial inclusion mitigates the effects of health challenges for the older generation in Ghana. The results imply that health outcomes may be improved by ensuring access to finance. Access to a bank account and financial services such as a loan may allow individuals to borrow to deal with unexpected health problems. A substantial part of the population in African countries has no access to adequate healthcare due to low incomes, which often hinders their productivity. Improvements in productivity levels are crucial for reduction in unemployment and poverty levels, and also for income generation for individuals who are self-employed.

Access to water has a positive effect on health; however, the coefficient is only significant in three models. Internet usage has a positive and significant effect on health in most models. Mimbi and Bankole (Citation2015) are of the view that the usage of ICT in health systems may lead to efficient outcomes through education, research and provision of healthcare services in remote areas. As expected, unemployment has a negative effect on health. Public health expenditure has an insignificant effect on health, which may be a reflection of insufficient spending on health in African countries (Novignon, Citation2015; Odhiambo et al., Citation2015). In line with a priori expectations, institutional quality and foreign direct investment are positive and significant in most specifications.

Financial inclusion has a positive and significant impact on income in four of the six specifications, as shown in . This supports the view of Levine (Citation1997), who suggests that the financial sector promotes income or GDP growth through savings mobilisation and investments, better risk management and facilitation of the exchange of goods and services. The finding supports those of Inoue and Hamori (Citation2016), who found that access to financial services promotes economic growth in SSA. The number of bank branches and outstanding deposits has an insignificant effect on incomes. The insignificance of the coefficient of outstanding deposits has been evident throughout the entire empirical analysis.

Table 3. Empirical results, dependent variable: INCOME.

Infrastructure indicators are positive in most models, which supports a priori expectations. Unemployment has a positive and significant effect on income in most, which contradicts theoretical expectations. Health expenditure is negatively related to income, which is in line with the findings from the earlier regressions in the study. Institutional quality promotes incomes, as shown by the positive sign in most models. Sound institutions, in particular property rights, may promote incomes through higher domestic and foreign investments as well as human capital levels (Mbulawa, Citation2015). The effect of FDI on income is largely insignificant in African countries.

outlines the effect of financial inclusion on educational attainment. The coefficients of the financial inclusion indicators are all positive and significant, with the exception of outstanding deposits. Financial services allow families, especially those in remote communities, to save for education by opening child savings accounts, thus promoting human capital levels. Furthermore, Anderson et al. (Citation2019) reported that financial inclusion is vital for youth development as access to financial services may encourage education and skills development. Furthermore, access to easier payment methods may encourage parents to keep their children at school for longer periods, which promotes higher levels of human capital development. Access to and usage of financial services should be encouraged as much as possible in order to promote human capital. One of the reasons for high poverty, inequality and unemployment levels is low levels of human capital, which render some individuals unemployable. Expenditure on education is vital, especially during the Fourth Industrial Revolution as demand for skilled workers is expected to increase.

Table 4. Empirical results, dependent variable: EDU.

With regards to infrastructure indicators, internet usage has a positive and significant effect on education in all models, while access to water is only significant in two models. Overall, evidence shows that infrastructure is crucial for educational outcomes. Unemployment, FDI and institutional quality are largely insignificant in the specification.

Overall, the empirical results indicate that both access to and usage of financial services is crucial for economic growth, as most of the measures were positive and significant in all of the models. Infrastructure indicators (access to water and internet usage) are important determinants of human development as they are positive in most models. The remaining control variables are not robust to a large extent. However, there is evidence of a positive effect of institutions on human development in several specifications.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have low human development levels, which continue to lag behind those of other world regions. Despite the high economic growth achieved since the 1990s, the socio-economic problems of high poverty levels, unemployment rates and inequality still remain in SSA countries. By promoting access to and usage of financial services, financial inclusion has the potential to make a significant contribution to the achievement of the SDGs.

The objective of the study was to investigate the effect of financial inclusion on human development in SSA. The study adopted the panel data approach to empirical analysis, and the GMM estimator was the chosen method of estimation due to potential endogeneity of the variables. Furthermore, the number of cross-sectional units exceeded the time-series components, which necessitated use of the GMM technique.

The findings are as follows. First, the study found that financial inclusion has a positive effect on human development proxied by the HDI. All the financial inclusion indicators have a positive effect on human development, with the exception of outstanding deposits that maintains an insignificant coefficient throughout the empirical analysis. The finding supports the notion that access to and usage of financial services promotes human development.

Second, the study went further and examined the effect of financial inclusion on the individual components of the HDI, namely, health, education and income. The findings support the view that financial inclusion improves health outcomes possibly by enabling households to save for health expenses. Financial inclusion has a positive effect on income, which supports the view that access to and usage of financial services promotes gross national income or GDP by enhancing savings and investments and facilitating the exchange of goods and services in an economy. Financial inclusion has a positive effect on the education component of human development. Financial inclusion may promote educational attainment and skills development by allowing families to save or borrow for educational expenditures. Furthermore, access to easier payment methods may encourage parents to keep their children at school for longer.

Overall, the findings show that financial inclusion has a positive effect on human development. Therefore, it is recommended that policymakers in Africa encourage or promote investments in the financial sector in order to broaden access to and usage of financial services. Investments in infrastructure, especially in remote areas, is vital for further growth in financial services. Policymakers should also raise awareness of the available financial services that may be used by households. Lack of usage of financial services may be due to lack of awareness of their availability. To ensure the availability of affordable financial services, collaboration between policymakers and financial service providers may be crucial. Affordable financial services may encourage the use of financial services, which in turn will boost human development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Acemoglu, D, Gallego, FA & Robinson, JA, 2014. Institutions, human capital and development. NBER Working paper No. 19933. http://www.nber.org /papers/w19933. [Accessed 1 October 2019].

- AfDB, OECD, UNDP & ECA, 2013. Human development in Africa. Economic Outlook. http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/en/outlook/humandevelopment. [Accessed 18 September 2019].

- African Development Bank, 2018. African economic outlook 2018. https://www.afdb.org. [Accessed 31 July 2019].

- Agarwal, P, 2015. Social sector expenditure and human development: Empirical analysis of Indian states. Indian Journal of Human Development 9(2), 173–89.

- Ake, C, 1981. A political economy of Africa (Vol. 4). Longman, London.

- Allen, F, Demirguc-Kunt, A, Klapper, L & Martinez-Peria, MS, 2016. The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding ownership and use of formal accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation 27, 1–30.

- Anderson, S, Hopkins, D & Valenzuela, M, 2019. The role of financial services in youth education and employment. Working Paper. CGAP, Washington, DC.

- Arellano, M & Bond, S, 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58(2), 277–97.

- Arellano, M & Bover, O, 1995. Another look at instrumental variables estimation of error component models. Journal of Econometrics 68, 29–51.

- Arisman, A, 2018. Determinants of human development index in ASEAN countries. Signifikan: Jurnal llmu Ekonomi 7(1), 113–22.

- Arora, RU, 2012. Financial inclusion and human capital in developing Asia: The Australian connection. Third World Quarterly 33(1), 177–97.

- Asongu, AS, 2013. How has mobile phone penetration stimulated financial development in Africa? Journal of African Business 14(1), 7–18.

- Asongu, AS & Nwachukwu, JC, 2016. The role of governance in mobile phones for inclusive human development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Technovation 55-56, 1–13.

- Bagli, S & Dutta, P, 2012. A study of financial inclusion in India. Radix International Journal of Economics and Business Management 1(8), 1–18.

- Baltagi, BH, 2005. Econometrics analysis of panel data. 3rd edn. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, West Sussex.

- Baum, CF, Schaffer, ME & Stillman, S, 2003. Instrumental variables and GMM: Estimation and testing. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 3(1), 1–31.

- Bell, A & Jones, R, 2015. Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modelling of time series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Science Research and Methods 3(1), 133–53.

- Bencivenga, VR & Smith, BD, 1991. Financial intermediation and endogenous growth. Review of Economic Studies 58(2), 195–209.

- Binder, M & Georgiadis, G, 2011. Determinants of human development: Capturing the role of institutions. CESIFO Working Paper No. 3397. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2031500. [Accessed 18 September 2019].

- Blundell, R & Bond, S, 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87, 115–43.

- Cámara, N & Tuesta, D, 2014. Measuring financial inclusion: a multidimensional index. BBVA Research Working Paper No. 14/26.

- Cheru, F, 2009. Development in Africa: The imperial project versus the national project and need for policy space. Review of African Political Economy 36(120), 275–8.

- de la Escosura, LP, 2013. Human development in Africa: A long-run perspective. Explorations in Economic History 50(2), 179–204.

- Demirguc-Kunt, A, Klapper, L & Singer, D, 2017. Financial inclusion and inclusive growth a review of recent empirical evidence. Development Research Group Finance and Private Sector Development Team. Policy Research Working Paper No. 8040. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/403611493134249446/Financial-inclusion-and-inclusive-growth-a-review-of-recent-empirical-evidence. [Accessed 20 September 2019].

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A, Klapper, L, Singer, D, Ansar, S & Hess, J, 2018. The global findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Dutta, SK & Singh, K, 2019. Variation and determinants of financial inclusion and association with human development: A cross country analysis. IIMB Management Review. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0970389616301574. [Accessed 17 September 2019].

- Eggleston, B, 2012. Utilitarianism. Encyclopedia of Applied Ethics 4, 452–8.

- Ejemeyovwi, JO, Osabuohien, ES, Johnson, OD & Bowale, EIK, 2019. Internet usage, innovation and human development nexus in Africa: The case of ECOWAS. Journal of Economic Structures 8(15), 1–16.

- Fanta, AB, Mutsonziwa, K, Goosen, R, Emanuel, M & Kettles, N, 2016. The role of mobile money in financial inclusion in the SADC region. Evidence using FinScope surveys. FinMark Trust Policy research paper No.03/2016.

- Fosu, A & Mwabu, G, 2010. Human development in Africa. UNDP-HDRO Occasional Papers, (2010/8).

- Gosavi, A, 2018. Can mobile money help firms mitigate the problem of access to finance in Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of African Business 19(3), 343–60.

- Greenwood, J & Jovanovic, B, 1990. Financial development, growth and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy 98(5), 1076–107.

- Gujarati, DN & Porter, DC, 2009. Basic econometrics. 5th edn. McGraw-Hill, Singapore.

- Gumede, V, 2017. Social policy for inclusive development in Africa. Third World Quarterly. http://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1374834. [Accessed 15 March 2020].

- Gupta, A, Chotia, V & Rao, NVM, 2014. Financial inclusion and human development: A state-wise analysis from India. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management II(5), 1–24.

- Gyasi, RM, Adam, AM & Phillips, DR, 2019. Financial inclusion, health-seeking behaviour, and health outcomes among older adults in Ghana. Research on Aging 41(8), 794–820.

- Hansen, LP, 1982. Large sample properties of generalised method of moments estimators. Econometrica 50, 1029–54.

- Hausman, DM & McPherson, MS, 2006. Economic analysis, moral philosophy and public policy. 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Heritage Foundation (Washington, D.C.), & Wall Street Journal (Firm), 1995. The index of economic freedom. Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC. https://www.worldcat.org/title/index-of-economic-freedom/oclc/34018540?page=citation. [Accessed 15 August 2019 ].

- Hill, RC, Griffiths, WE & Lim, GC, 2012. Principles of econometrics. Wiley, Asia.

- Hsiao, C, 2003. Analysis of panel data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- IMF, 2018. Financial access survey. The International Monetary Fund. https://data.imf.org. [Accessed 10 July 2019].

- Inoue, T & Hamori, S, 2016. Financial access and economic growth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 52(3), 743–53.

- Klapper, L, El-Zoghbi, M & Hess, J, 2016. Achieving the sustainable development goals: The role of financial inclusion. www.cgap.org. [Accessed 20 July 2019].

- Kuri, PK & Laha, A, 2011. Financial inclusion and human development in India: An inter-state analysis. Indian Journal of Human Development 5(1), 61–77.

- Kuriakose, F & Iyer, DK, 2015. Understanding financial inclusion through deconstructing human development approach and capabilities theory. Sahulat Journal of Microfinance 1(3), 13–31.

- Lee, S-O, Hong, A & Hwang, J, 2017. ICT diffusion as a determinant of human progress. Information Technology for Development 23(4), 687–705.

- Levine, R, 1997. Financial development and economic growth: Views and Agenda. Journal of Economic Literature 35, 688–726.

- Masiyandima, N, Mlambo, K & Nyarota, S, 2017. Financial inclusion and quality of livelihood in Zimbabwe. https://2017.essa.org.za/fullpaper/essa_3578.pdf. [Accessed 15 October 2019].

- Mbulawa, S, 2015. Determinants of financial development in Southern Africa Development Community (SADC): Do institutions matter? European Journal of Accounting Auditing and Finance Research 3(6), 39–62.

- Mimbi, L & Bankole, F, 2015. ICT and health system performance in Africa: A multi-method approach. 26th Australasian Conference on Information System. 30th Nov-04th Dec 2015, Adelaide, Australia.

- Mohanty, AK, Nayak, NC & Chatterjee, B, 2016. Does infrastructure affect human development? Evidenced from Odisha, India. Journal of Infrastructure Development 8(1), 1–26.

- Morgan, L & Churchill, C, 2018. Financial inclusion and health: How the financial services industry is responding to health risks. International Labour Office Geneva: ILO, 2018. Paper No. 51. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/documents/genericdocument/wcms_633702.pdf. [Accessed 10 September 2019].

- Nanda, K & Kaur, M, 2016. Financial inclusion and human development: A cross-country evidence. Management and Labour Studies 41(2), 127–53.

- National Research Council, 1996. Measuring and improving infrastructure performance. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/4929. [Accessed 21 May 2020].

- Novignon, J, 2015. On the efficiency of public health expenditure in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does corruption and quality of public institutions matter? MPRA Paper No. 39195. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/39195/. [Accessed 2 October 2019].

- Nussbaum, M, 2000. Women and human development. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Nussbaum, M, 2001. Upheaval of thought: The intelligence of emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Odhiambo, SA, Wambugu, A & Kiriti-Ng’ang’a, T, 2015. Convergence of health expenditure in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from a dynamic panel. Journal of Economic and Sustainable Development 6(6), 185–205.

- Pesaran, MH, Shin, Y & Smith, RP, 1999. Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association 94(446), 621–34.

- Raichoudhury, A, 2016. Financial inclusion and human development: Across country analysis. Asian Journal of Business Research 6(1), 34–48.

- Rastogi, C & Gaikwad, SM, 2017. A study on determinants of human capital development in BRICS nations. FIIB Business Review 6(3), 38–50.

- Roodman, D, 2009. How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 9(1), 86–136.

- Saint-Paul, G, 1992. Technological choice, financial markets and economic development. European Economic Review 36(4), 763–81.

- Sarma, M & Pais, J, 2011. Financial inclusion and development. Journal of International Development 23, 613–28.

- Schumpeter, J, 1912. The theory of economic development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Sen, A, 1987. The standard of living. G. Hawthorne. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Sen, A, 1992. Inequality re-examined. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Shuaibu, M & Oladayo, PT, 2016. Determinants of human capital development in Africa: A panel data analysis. Oeconomia Copernicana 7(4), 523–49.

- Skousen, M, 2001. The making of modern economics: The lives and ideas of great thinkers. ME Sharpe, New York, USA.

- Taner, MT, Sezen, B & Mihci, H, 2011. An alternative human development index considering unemployment. South East European Journal of Economics and Business 6(1), 45–60.

- Tchamyou, SV & Asongu, AS, 2017. Information sharing and financial sector development in Africa. Journal of African Business 18(1), 24–49.

- Tita, AF & Aziakpono, MJ, 2017. The effect of financial inclusion on welfare in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from disaggregated data. ERSA working paper 679.

- UNDP, 2018. Human development indices and indicators. 2018 statistical update. www.undp.org. [Accessed 9 September 2019].

- United Nations Global Compact & KPMG International, 2015. SDG industry matrix; financial services. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issuesdoc/development/SDGMatrixFinancialSvcs.pdf. [Accessed 14 October 2019].

- UNSGSA, The Better Than Cash Alliance, UNCDF & World Bank, 2018. Igniting SDG progress through digital financial inclusion.

- Voica, MC, 2017. Financial inclusion as tool for sustainable development. Romanian Journal of Economics 44(1), 121–9.

- Wooldridge, JM, 2002. Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data. MIT Press, London.

- World Bank, 2019. World Development Indicators. http://data.worldbank.org. [Accessed 14 July 2019 ].