ABSTRACT

Communities play an important role in the process of tourism development and their support is essential for the development, planning and successful operation of tourism development, and for attainment of sustainable livelihoods. Community-driven tourism projects are supposed to benefit the community and contribute to their livelihoods. However, the majority of community-driven tourism projects ultimately do not benefit communities because of poorly or mismanaged institutional structures. This paper presents a review of various planning and management strategies that have been used for community-driven tourism projects and also identifies some case studies where applications of some of these strategies have worked. Critical sustainable tourism indicators were adopted to provide the basis for a stakeholder-oriented model for community-driven tourism projects. Furthermore, an all-stakeholder-oriented model is proposed where the community is at the centre with an element of co-management with other sectors, bearing in mind the sustainability of communities’ livelihoods.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the most important social and economic fields of all time, and is an agent of social change subject to objective laws of social development (Baggio, Citation2008; Lew & Cheer, Citation2018; Benner, Citation2019). Despite it being one of the growing industries in the global economy, many governments and entrepreneurs have invested in the tourism industry with minimum planning and preparation and, in some cases, without considering tourism’s detrimental impacts (Tosun & Timothy, Citation2001; Mason, Citation2015). Furthermore, tourism operations depends on local communities for labour, entrepreneurship and goodwill (Blackstock, Citation2005; Košić et al., Citation2017). Their participation in tourism development is heavily dependent on the benefits accrued and therefore their involvement is detrimental to the sustainability of the industry (Košić et al., Citation2017).

The second section of this chapter explores the benefits of tourism that are considered key to communities, analysing sustainable tourism in regard to community livelihoods. For communities to achieve maximum benefits the projects need to be properly managed. The third section appraises and deliberates on various planning and management strategies in relation to the development of tourism. Considering sustainable tourism indicators as vital pointers for community-driven tourism projects, an all-stakeholder-oriented model is proposed. The fourth section presents conclusions.

2. Benefits of tourism

Being an economic activity, the revenues generated from tourism have become a very important resource and a key factor in the balance of payment for many countries and regions; it has been and still is a major contributor to their economic growth (Rate et al., Citation2018). Tourism has been described (or refined) by several governments and academics as relating to fields such as economics, sociology, cultural anthropology and geography (Theobald, Citation2005). Economists are concerned with tourism’s contributions to the economy and the economic development of a destination area (Mason, Citation2015). Chisova (Citation2015) views tourism from a socio-economic perspective and describes it as a twentieth-century phenomenon involving not only the travelling individual but also a process engaging many people and multidisciplinary activities. Rate et al. (Citation2018: 5) consider the changing business environment, the pace of which is driven by ever-changing supply and demand in terms of the emergence of technology and new holiday packages. They further analyse foreign exchange rates and the steadiness of expenditure, employment and other monetary factors that contribute to the growth of the global economy. Rate et al. also identify tourism as a multifaceted contributor to the economy but question how it contributes to communities in rural areas.

Tourism has been assumed to relate well to rural communities by providing many benefits to them. Because tourism is labour intensive, it provides job opportunities (UNWTO, Citation2015). It is seen to promote the creation of small and micro enterprises (Zapata, Citation2011). Tourism is known to support the construction of public facilities, amenities and infrastructure, as well as promote the preservation and conservation of the environment and culture of the residents (Yanes et al., Citation2019). Since tourism is consumed at the point of production, it can provide indirect income as well as direct purchases, hence boosting the economy of an area. Most rural areas are rich with natural resources that are used as tourist attractions. These resources are owned by local communities and thus need to be tapped by them to benefit from tourism. To date, despite such prospects and the increasing attention focusing on sustainable tourism to benefit host communities, there seem to be few or no benefits whatsoever to the communities residing in the vicinity of tourist attractions. There is a need for properly organised programmes to enable communities to tap into and benefit from tourism. Community-driven tourism projects, if well managed, allow rural communities to benefit fully from tourism. The contribution of tourism to rural communities’ sustainable livelihoods is discussed below.

2.1. Tourism and community livelihoods

The formation of tourism areas and related developments sometimes results in the displacement and relocation of local communities (Sirima & Backman, Citation2013; Su et al., Citation2016). This disrupts economic arrangements and social and political administrations and processes (Sirima & Backman, Citation2013). As important tourism stakeholders, the host communities and their livelihoods are critical to tourism sustainability and development of the region. The Department for International Development (DFID, Citation1999), Allisona and Horemans (Citation2006) and Serrat (Citation2017) advocate for a people-centred, holistic and sustainable livelihood approach, based around five key features: livelihood assets (economic, social, human, physical and natural; DFID, Citation1999); transforming structures and processes (laws, policies, culture and institutions; Scoones, Citation1998; Carney, Citation2003); vulnerability context (shocks, trends and seasonality); strategies (activities employed to generate means of household survival; DFID, Citation2000); and outcomes (the successes and objectives achieved by livelihood strategies; Carney, Citation2003).

As a rural livelihood choice, tourism needs to be understood in comparison with other traditional rural livelihoods (e.g. agriculture, forestry and so on) (Stone and Nyaupane, Citation2017). In this sense, tourism is a livelihood opportunity and its distinctiveness can be observed from the angle of production-consumption (Shen et al., Citation2008). Tourism ‘products’ include tourism-oriented products (e.g. accommodation, food services, transportation), common resident-oriented products (e.g. infrastructure, security, hospitals) and contextual tourism essentials (i.e. landscape, cultural and public attractions). Kheiri and Nasihatkon (Citation2016) argue that sustainable livelihood (SL) tourism is a convergence of sustainable, rural and tourism development. Not only should SL be viewed and analysed in the context of rural development it should also be seen from the perspective of tourism (Mitchell & Hall, Citation2005; Saarinen, Citation2007).

Several frameworks attempt to comprehend the intricate relationships among tourism, development and community livelihoods (Kheiri and Nasihatkon, Citation2016; Su et al., Citation2016; Mbaiwa, Citation2018). Salafsky and Wollenberg (Citation2000) developed a framework to link biodiversity conservation and people’s livelihoods. They argue that, when people’s livelihoods are dependent on biodiversity only, there is a tendency to exploit some of these biological resources to extinction. The common approach to conserving biodiversity has therefore been the creation of parks and protected areas that exclude people’s livelihoods (Adams et al., Citation2004; Mbaiwa & Stronza, Citation2010; Nyaupane & Poudel, Citation2011). Anaya and Espírito-Santo (Citation2018), however, noted that the strategy of creating protected areas caused foreclosure of future land use options and thereby denied local communities of other potential livelihood opportunities. The creation of protected areas may also have resulted in the eviction of original occupiers from their land, subjecting them to further poverty (Adams et al., Citation2004). Therefore, Salafsky and Wollenberg (Citation2000) postulated that there was a need to provide an alternative source of livelihood to communities, such as economic substitution activities. This prompted a proposal for a linked incentives model whereby livelihoods are the main drivers of biodiversity. The linked incentives model suggested livelihood interventions such as handicrafts, ecotourism, beehives and butterfly production, which became the driving force behind conservation efforts (Salafsky & Wollenberg, Citation2000). This gave local communities an opportunity to benefit directly from biodiversity efforts and, consequently, motivated them to respond to external threats to such biodiversity (e.g. corporate logging). Additionally, previous studies have argued that, for tourism to realise sustainable rural development, it is necessary to integrate sustainable livelihoods and tourism (Shen et al., Citation2008; Mbaiwa & Stronza, Citation2010; Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2018). Shen et al. (Citation2008) suggested a tourism–livelihood approach that is broad and includes core livelihood assets (natural, human, economic, social and physical capital), involves activities related to tourism and provides a means of making a living.

According to Su et al., a sustainable tourism livelihood is embedded in a tourism setting within which it can cope with vulnerability and achieve livelihood outcomes that are economically, socially, environmentally and institutionally sustainable without undermining other livelihoods. These sentiments were emphasised by Chambers and Conway (Citation1992) and Ellis (Citation2000). Thus, sustainable tourism can only exist in a sustainable location (Su et al., Citation2016). The sustainable livelihood approach to tourism proposed by Shen et al. (Citation2008) provided broad intervention measures carried out by general stakeholders and focused on the macro-level tourist industry (international and domestic). There is a need, therefore, for new theories on sustainable tourism at the household (micro) level (Su et al., Citation2016). Rural development is best executed if local communities are involved in the initial planning process, the operation and management of the development project and major decision making (Blackstock, Citation2005; Tosun, Citation2006; Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2017). Su et al. argue that community-based tourism projects provide a sustainable livelihood if the communities have access to their capital assets. Moreover, communities that are well-informed regarding their priorities and can legitimately utilise all of the resources at their disposal to create sustainable livelihoods. Furthermore, the sustainable livelihood concept is driven by the argument that development must be based on an integrated system (social, environmental and economic) approach to management, with an organisational culture and values that support collaborative sharing of knowledge and encourage participation of all stakeholders (Karagiannis & Apostolou, Citation2004). Previous studies maintain that the poor themselves are often aware of their living conditions and needs and should therefore be involved in the designing of policies and projects intended to better their lives (Jacobs & Makaudze, Citation2012; Sachikonye et al., Citation2016; Serrat, Citation2017).

In most destinations, especially in rural areas, natural resources are the attractions, which are owned by the host communities. It is here that community-driven tourism projects (CDTPs) should be introduced, to protect and conserve such resources and ensure the communities that rightfully own them reap the benefits. Boniface et al. (Citation2016) noted that destinations deserve more attention than the other components of CDTPs because they not only attract tourists but also have a huge impact on the host community and the environment, thus necessitating sustainable planning and management. It is vital that tourism project developers devise a sustainable method for tourism planning and management (Islam et al., Citation2018). The following section therefore reviews literature on tourism planning and management approaches and later looks at various management models used in different community tourism projects.

3. Tourism planning and management

According to Williams and Hall (Citation2002:126), planning is, or should be, a process for anticipating and ordering change that is forward looking, that seeks optimal ‘solutions, that is designed to increase and ideally maximise possible development benefits and, that will produce predictable outcomes’. McCabe et al. (Citation2000: 235) state that, ‘A plan enables us to identify where we are going from here and how to get there – in other words it should clarify the path that is to be taken and the outcomes or end results'.

Tosun and Jenkins (Citation1998) defined tourism planning as a process based on research and evaluation, which is intended to enhance the probable contribution of tourism to human welfare and environmental quality. This definition reveals that tourism planning not only involves tourists and their economic input but also stresses achieving set developmental goals (Tosun & Timothy, Citation2001). Additionally, tourism planning comprises a decision-making process involving the tourism industry and other sectors of the economy and various sub-national areas and different types of tourism (Tosun & Timothy, Citation2001; Mason, Citation2015). It is important to note that tourism planning is not just a process steered by government but one that includes all stakeholders (Tosun, Citation2002; Aas et al., Citation2005; Marzuki & James, Citation2012; Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2017; Latip et al., Citation2018). Saarinen et al. (Citation2017) assert that tourism planning should be understood as a potential instrument for guiding tourism on to a development trail that generates benefits and wellbeing beyond the industry and its principal processes. In addition, they emphasise that extensive socio-economic development in tourism is not an automatic route to success and therefore a poorly planned tourism project can produce unexpected consequences.

The community is an important stakeholder and should take centre stage in the planning and implementation of tourism project development (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2017). In order to create a more sustainable industry, Rasoolimanesh et al. (Citation2017) stressed that community-based tourism should be focused on the involvement of the host community in terms of planning and maintaining tourism development. This is because the host communities literally own the natural resources on which tourism development hinges. Sustainable development is the ultimate goal for community-development projects (Peerapun, Citation2018) and, since tourism can play an important role in diverse economic development, cautious tourism planning that involves the community in all stages of development is necessary (Byrd et al., Citation2008). Tourism as an economic activity has the potential to create employment and subsequently improve the livelihoods of host communities (Owuor et al., Citation2017). Therefore, programmes that encourage the participation of all stakeholders in tourism development go a long way in terms of poverty alleviation in the destination areas (Waligo et al., Citation2013). The following sections briefly examine tourism planning strategies relevant to this study. It is vital to investigate different planning and management strategies in order to be able to recommend an appropriate management model for CDTPs.

3.1. Participatory planning and management

The implementation of an operational community participation process is key to improving the quality of tourism plans, protecting tourism resources and balancing the numerous benefits from tourism (Tosun & Timothy, 2003). According to Peerapun, (Citation2018: 149), ‘Participatory Planning is a set of processes through which varied groups and interests engross together in reaching for a consensus on a plan and its implementation.’ Participatory planning can be introduced by any of the parties and the procedures and schedules they will follow are likely to be negotiated and agreed upon by participants (Peerapun, Citation2018). Stakeholders are all those who need to be involved and considered in attaining project goals and whose participation and support are vital to a project’s success (Golder, Citation2005). Participation of all relevant stakeholders is key and therefore it is important for any developer or planner to analyse the various groups of stakeholders and types of participation (Treves, Wallace, & White, 2009; Peerapun, 2018; Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2017).

There are five levels of participation: informing, consultation, involvement, collaboration and empowerment (Golder, Citation2005; Peerapun, Citation2018). The planner can correspond with suitable stakeholders at each level of participation (Peerapun, Citation2018). In addition, Golder (Citation2005) suggests that full participation of all stakeholders is key and so is analysis of those stakeholders. This is because stakeholder participation analysis helps identify the interests of all stakeholders who may affect or be affected by the project, probable areas of conflict, risks that could jeopardise the initiative and relationships that can be built during implementation (Golder, Citation2005)

Full participation of stakeholders in both project design and implementation is important because stakeholder participation gives people some say over how projects or policies may affect their lives (Golder, Citation2005); Peerapun, Citation2018). According to Pugh and Potter (Citation2018), community participation in development results in socio-economic empowerment, good marketing relations with wider networks and hence access to funds. Therefore, participation of all stakeholders in CDTPs is key.

3.2. Protected area management model

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, Citation1994:9) defined a protected area as ‘an area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means'. IUCN then grouped protected areas in to six categories, namely: strict nature reserve, national park, natural monument or feature, habitat/species management area, protected landscape/seascape area, and protected area with sustainable use of natural resources(Stuart et al., Citation1990; UNEP-WCMC, Citation2016). The main objective of protection is to safeguard regions that have established a distinct and valuable ecological, biological, cultural or scenic character (IUCN, Citation1994; Masud et al., Citation2017).

From the 1940s onwards, the protected area model was seen as one of the best approaches to conservation (Stuart et al., Citation1990). The protected area model involved identifying an area endowed with rich natural resources or physical features (Stuart et al., Citation1990; Okello, Citation2005) and moving the human population away from their traditional habitats (Badola et al., Citation2018). This meant displacing those people and, in some cases, denying them access to natural resources that were, in most cases, the source of their livelihood and of food and water for their domestic animals (Okello, Citation2005). Displacing people and preventing them from accessing resources in protected areas led to them feeling a sense of resentment regarding conservation of resources such as wildlife (Okello, Citation2005; Figueroa & Rotarou, Citation2016; Badola et al., Citation2018). In most cases the local community is excluded from the initial idea and planning of conservation methods (Okello, Citation2005). This has resulted in human/wildlife conflict in areas adjacent to or surrounding many national parks in Africa.

3.3. Institutional management

Institutions are the conventions, norms and formal rules of a society that regulate life, support values and protect the interests of the people (Vatn, Citation2010). Institutions can be categorised into two groups: formal and informal. Formal institutions follow codified rules while informal institutions adhere to socially shared, openly codified and unwritten rules (Li & Abiad, Citation1990; Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004; Torniainen & Saastamoinen, Citation2007; Holmes et al., Citation2013). Institutions via formal and informal rules determine the nature of tourism activities and influence tourists’ behaviour. Institutions are meant to provide incentives or deterrents to people that determine their direct or indirect role in shaping the nature of tourism in a given area (Badola et al., Citation2018). They control tourism activities and their impact on the ecological, social and cultural values of an area, and the manner in which their benefits are shared among the diverse stakeholders (Liu et al., Citation2017).

Earlier scholars recognise that, in developing countries, representation of the poor in natural resources management is often informal and carried out by local-level institutions (Thomas, Citation2004; Bjarnegård, Citation2013; Chappell & Waylen, Citation2013; Olson, Citation2014). Formal institutions, in contrast, are largely preserved as the stronghold of men, the educated and the rich (Thomas, Citation2004; Badola et al., Citation2018). Strong local institutions enhance local communities’ resilience in opposing social, cultural and ecological changes and ensuring equitable sharing of benefits (Ogra & Badola, Citation2014).

In the early seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the African people preserved and conserved forests as holy grounds, as shrines and as providers of traditional medicine (Reid & Turner, Citation2004). Subsequently, traditional African institutions that prevented the overuse of natural resources were replaced by western institutions and practices, such as courts of law, fines and fences (Reid, Citation2001; Reid & Turner, Citation2004). Later, in the 1990s, communal property institutions were formed, some of which became the foundation of the community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) approach, such as CAMPFIRE of Zimbabwe (Fabricius et al., Citation2013; Ntuli & Muchapondwa, Citation2018). Some CBNRMs are currently under the control of communal property institutions in Africa, such as the Makuleke Contractual Park in South Africa and the Mara Conservancies of Kenya (Fabricius et al., Citation2013).

The institutions have rights and control over benefits accrued from ecosystems and other natural resources (Ntuli & Muchapondwa, Citation2018). Nonetheless, the literature has shown that institutions without proper guidelines to control human behaviour are likely to result in the over-exploitation of natural resources (Reid & Turner, Citation2004; Ntuli & Muchapondwa, Citation2018). Apparently, many communities are not able to manage their resources sustainably because they are not represented equitably in these institutions (Schnegg, Citation2018). Additionally, Ntuli and Muchapondwa (Citation2018) assert that communities do not have easy access to their natural resources because they encounter institutional restrictions and bureaucracy. Since these institutions are meant to guard and manage common-pool resources, they need to be governed by all stakeholders to ensure communities’ sustainable livelihoods.

3.4. Adaptive co-management

According to Hasselman (Citation2017), adaptive co-management (ACM) empowers resource users and managers in terms of experimentation, monitoring, deliberation and responsive management of local resources, supported by, and working with, various organisations at different levels. Tourism destination management can be problematic if and when tourism takes place in significant natural and cultural locations dedicated to the conservation of species, ecosystems, landscapes or culture (Saarinen, Citation2006; Saarinen et al., Citation2017; Islam et al., Citation2018). Tourism in protected areas may not reach its potential due to poor management resulting in little cooperation and coordination among stakeholders, which sometimes leads to conflict (Islam et al., Citation2018). It is imperative therefore that managers observe the distinctive features of AC|M, which are essential for monitoring the management of tourism destinations or protected areas (Armitage et al., Citation2010). These features include shared vision, problem definition, interaction and collaboration among multi-scaled actors, distributed control across multi-levels and shared responsibilities and decision making.

The main aim of ACM is to resolve natural resource management conflict and to function as a means of enhancing governance systems in protected areas or tourism destinations. The following is a case study conducted by Stone and Nyaupane, (Citation2017) on the Chobe Enclave Conservation Trust (CECT), next to Chobe National Park in Botswana. The CECT practises the three tourism planning and management models discussed above: participatory planning, co-management and institutional management (see Box 1).

According to Stone and Nyaupane (Citation2017), the CECT was formed in 1992 to encourage community participation in tourism and wildlife conservation. It is a community institution that practises community-based tourism and comprises five villages: Mabele, Kavimba, Kachikau, Satau and Parakarungu. The CECT is run by a board of trustees from these member villages. The villages are in a buffer zone divided into two controlled hunting areas (CHAs) used for hunting tourism and photographic tourism. The inhabitants of the five villages are the Basubiya tribe, who predominantly depend on both subsistence pastoral and arable farming complemented by tourism wages for those who are employed in the tourism establishments. Two members are elected through general membership from each participating village. Altogether, there are 15 members on the board of trustees. The CECT owns CHAs 1 and 2, a community lodge, six tractors, a brick-moulding workshop, two camping sites and two administrative offices.

Participation in tourism by the CECT is a collective action that harmonises the role of park and community livelihoods in resource use, builds community capitals and enhances the vitality of natural capital. Through the collective action of the CECT communities, mutual trust exists between the community and government, which results in low rates of reported illegal hunting, suggesting a positive relationship between tourism and the Chobe National Park. Due to employment in the tourism facilities, people’s diet has improved as has food security. Since the people of Chobe villages are part of the tourism practices in the area, there is a reduction in poaching because they understand the importance of wildlife in tourism.

Tourism takes place in a setting comprising both human and natural features (Mason, Citation2015). The human environment includes economic, social and cultural aspects (Lis, Citation2009; Moscardo, Citation2011; Huang & Huang, Citation2018). In a real setting, the human environment and the natural environment are linked, and human activities are both affected by and have an effect on the natural environment (Mason, Citation2015). Based on the models reviewed above, it can be concluded that, regardless of the management model, involving the community in management is vital for the success of all tourism projects and, in order to manage projects appropriately, stakeholders need to understand the management model best suited for each project. The following section discusses the sustainable tourism indicators that are considered fundamental for CDTPs.

3.5. Indicators of sustainable tourism for community-driven projects

Sustainable tourism is an element of sustainable development that encourages minimisation of the socio-economic impacts of tourism and maximises the socio-economic benefits to the host community (UNWTO, Citation2007; Edgell, Citation2019). Sustainable tourism is not a discrete or special form of tourism. Rather, all forms of tourism should strive to be more sustainable (UNEP & UNWTO, Citation2005). Sustainable tourism indicators exist to influence the growth of tourism (Chisova, Citation2015); these are: economic, social, cultural, environmental and managerial. For communities to gain maximum benefit from tourism, there is a need for tourism sustainability, which is achieved through focusing on the above indicators for monitoring sustainable tourism (Choi & Sirakaya, Citation2006)

The sustainable tourism indicators are vital tools in the tourism planning, management and monitoring processes and also provide accurate information for decision making (UNWTO, Citation2007). They focus on issues relating to economic sustainability, conservation and preservation of cultural assets and social values, and management of projects (Choi & Sirakaya, Citation2006; Bulatović & Rajović, Citation2016). The sustainable tourism indicators for community-driven projects involve utilisation of natural resources while also ensuring minimal destruction of the ecosystem and conservation of biodiversity. This study generates sustainable tourism indicators through synchronisation, adoption and review of the sustainable tourism indicators provided by UNWTO (Citation2007), Choi and Sirakaya (Citation2006), Chisova (Citation2015) and Bulatović and Rajović (Citation2016) (see and ). The indicators also point out the importance of ensuring community access to natural resources as well as involving community members in conservation. Sustainable tourism preserves and conserves cultures and values the beliefs and traditions of local communities. Communities need to benefit economically from tourism.

The CDTPs need to create employment through tourist generation activities such as tour guiding, selling of arts and crafts to tourists and so on. For projects to succeed and benefit the community, there is a need for the proper management of tourism projects. Their management structures need to be exclusive, holistic and community oriented. Tourism projects ought to purchase services and agricultural supplies from the community, as well as provide a market for traditional artefacts made by the community. Through these efforts the community ought to earn a living for their households.

Development of tourism-based community capital assets improves the overall wellbeing of the community (Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2017). Much research has maintained that if communities are to benefit from tourism then community participation in tourism development is key (Blackstock, Citation2005; Rasoolimanesh & Jaafar, Citation2016; Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2017). Nevertheless, limited literature has supported the notion that added benefits are accrued if the communities have total control of projects whereby they collectively make decisions and execute them (Putnam, Citation2000; Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2018). For community projects to succeed, all stakeholders need to be involved in their operation. Consequently, guided by the sustainable tourism indicators, this study proposes an all-stakeholder-oriented model of management for CDTPs whereby communities have majority shares in projects.

3.6. All-stakeholder-oriented model for CDTPs

Previous tourism studies identified different stakeholder types, with many typologies typically merging into six broad categories: tourists, industry, local community, government, special interest groups and educational institutions (Place, Hall, & Lew, Citation1998; Markwick, Citation2000; Getz & Timur, Citation2012; Mason, Citation2015). These stakeholder groups influence tourism development in many ways, including tourism supply and demand, regulation, management of the impact of tourism, human resources and research (Waligo et al., Citation2013). Notably, Waligo et al. (Citation2013:346) identified the key factors influencing stakeholder involvement in sustainable tourism as ‘leadership quality, information quality and accessibility, stakeholder mindsets, stakeholder involvement capacity, stakeholder relationships and implementation priorities’. As stakeholders are influential in terms of achieving the sustainability objectives of tourism development, their opinions on how to get involved are fundamental (Getz & Timur, Citation2012; Waligo et al., Citation2013). In this instance, involving all stakeholders at the initiation, planning, operation and decision making stages of tourism development will eliminate conflict that may derail progress in the development of tourism projects. Furthermore, stakeholders are a fundamental component of sustainable tourism and therefore stakeholder participation is expected to facilitate the implementation of sustainable community-driven tourism projects.

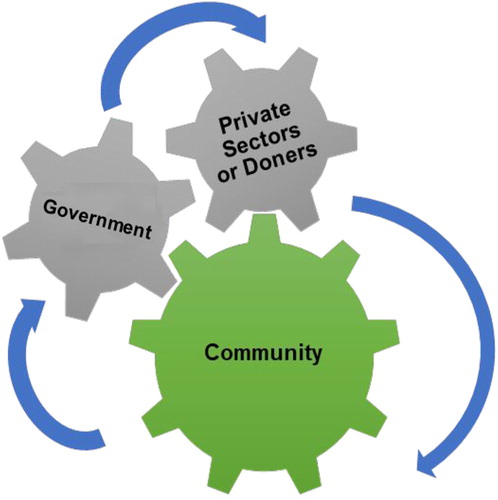

In pursuit of benefit sharing and the success of tourism projects, this study proposes an all-stakeholder-orientated model of management for community driven projects that will assist in achieving maximum benefits for sustainable livelihoods of communities. Observing the sustainable tourism indicators for community-driven projects, the community ought to be the major beneficiaries of these projects. This is because the rural communities own the natural and cultural resources that are tourist attractions. Consequently, the communities need to be involved in the initiation, planning, operation and management of the projects. Other players who might be involved in projects, such as the government, some donors or non-governmental organisations (NGOs), ought to consult with the community on every plan or development. They also need to work with the community towards the accomplishment of the objectives of such projects. The management structure, such as heads of sections, community mobilisers, constitution and major decision making, ought to be led by the community or their representatives. ) illustrates this model.

While complete community-driven projects are often seen as vital to any community’s growth and success, the planning and management process by which the projects are operated is key for attainment of livelihoods.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, the literature has revealed that CDTPs are mandated to contribute to the community’s wellbeing as well as keep tourism alive as an industry. For this to happen, sustainable tourism practices need to be present. The sustainable tourism indicators should then act as pointers for community-driven projects for sustainable livelihoods. The CDTPs’ management should be people-centred, holistic and inclusive. The study reviewed several tourism planning and management models, amongst them participatory planning, adaptive co-management, the protected areas model and the institutional management model. Tourism contributes enormously to community livelihoods and hence the communities need to participate in tourism projects. The study therefore proposed an all-stakeholder-oriented management model that has the community at the centre, with an element of co-management with other sectors such as the government, the private sector or NGOs. All stakeholders need to be involved from the initiation of the concept to the end and in major decision making concerning the operation of the project. The communities need to drive their own tourism projects for sustainable livelihoods. This study recommends further investigation into the impact of CDTPs on community livelihoods through tourism community capital assets.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aas, C, Ladkin, A & Fletcher, J, 2005. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Annals of Tourism Research 32(1), 28–48. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.005

- Adams, WM, Aveling, R, Brockington, D, Dickson, B, Elliott, J, Hutton, J, … & Wolmer, W, 2004. Biodiversity conservation and the eradication of poverty. science, 306(5699), 1146–1149.

- Allison, EH & Horemans, B, 2006. Putting the principles of the sustainable livelihoods approach into fisheries development policy and practice. Marine Policy 30(6), 757–766.

- Anaya, FC, & Espírito-Santo, MM, 2018. Protected areas and territorial exclusion of traditional communities. Ecology and Society, 23(1).

- Armitage, D, Berkes, F & Doubleday, N, 2010. Adaptive co-management: collaboration, learning, and multi-level governance. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press.

- Badola, R, Hussain, SA, Dobriyal, P, Manral, U, Barthwal, S, Rastogi, A & Gill, AK, 2018. Institutional arrangements for managing tourism in the Indian Himalayan protected areas. Tourism Management 66, 1–12.

- Baggio, R, 2008. Symptoms of complexity in a tourism system. Tourism Analysis 13(1), 1–20.

- Benner, M, 2019. From overtourism to sustainability: A research agenda for qualitative tourism development in the Adriatic.

- Bjarnegård, E, 2013. Gender, informal institutions and political recruitment: Explaining male dominance in parliamentary representation. Hampshire, UK: Springer.

- Blackstock, K, 2005. A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal 40(1), 39–49.

- Boniface, B, Cooper, R & Cooper, C, 2016. Worldwide destinations: The geography of travel and tourism. London, UK: Routledge.

- Bulatović, J & Rajović, G, 2016. Applying sustainable tourism indicators to community-based Ecotourism tourist village Eco-katun Štavna. European Journal of Economic Studies 2, 309–330.

- Byrd, ET, Cárdenas, DA & Greenwood, JB, 2008. Factors of stakeholder understanding of tourism: The case of Eastern North Carolina. Tourism and Hospitality Research 8(3), 192–204.

- Carney, D, 2003. Sustainable livelihoods approaches: Progress and possibilities for change. London, Department for International Development.

- Chambers, R, & Conway, G, 1992. Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. Institute of Development Studies, UK.

- Chappell, L & Waylen, G, 2013. Gender and the hidden life of institutions. Public Administration 91(3), 599–615.

- Chisova, J, 2015. Transformation of approaches to the definition of «tourism» in the context of socio-economic importance. Socio-economic Research Bulletin 59(4), 26–31.

- Choi, HC & Sirakaya, E, 2006. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management 27(6), 1274–1289.

- DFID, UK, 1999. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. London: DFID, 445.

- DFID, GS, 2000. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets, Section 2. Framework. UK.

- Edgell Sr, DL, 2019. Managing sustainable tourism: A legacy for the future. Routledge, New York.

- Ellis, F, 2000. Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford University Press.

- Fabricius, C, Koch, E, Turner, S & Magome, H, 2013. Rights resources and rural development: community-based natural resource management in Southern Africa. London, UK: Routledge.

- Figueroa, B & Rotarou, E, 2016. Sustainable development or eco-collapse: Lessons for tourism and development from Easter Island. Sustainability 8(11), 1–26.

- Getz, D & Timur, S, 2012. 12 stakeholder involvement in sustainable tourism: balancing the voices. Global Tourism 230, 230–247.

- Golder, B, 2005. Cross-Cutting Tool, Stakeholder Analysis. A resource to support the implementation of the WWF Standards of Conservation Project and Programme Management. Resources for Implementing the WWF Standards. Retrieved from https://intranet.panda.org/documents/folder.cfm?uFolderID=60976.

- Hasselman, L, 2017. Adaptive management; adaptive co-management; adaptive governance: what’s the difference? Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 24(1), 31–46.

- Helmke, G & Levitsky, S, 2004. Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Perspectives on Politics 2(4), 725–740.

- Holmes Jr RM, Miller, T, Hitt, MA & Salmador, MP, 2013. The interrelationships among informal institutions, formal institutions, and inward foreign direct investment. Journal of Management 39(2), 531–566.

- Huang, SS & Huang, J, 2018. Effects of destination social Responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and Perceived quality of life. Journal of Hospitality AND Tourism Research 42(7), 1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/1096348016671395

- Islam, MW, Ruhanen, L & Ritchie, BW, 2018. Adaptive co-management: A novel approach to tourism destination governance? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 37, 97–106.

- IUCN, 1994. IUCN red list categories. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland.

- IUCN, 2016. A global standard for the identification of Key Biodiversity. Retrieved from Hawai.

- Jacobs, P, & Makaudze, E, 2012. Understanding rural livelihoods in the West Coast district, South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 29(4), 574–587.

- Karagiannis, S, & Apostolou, A, 2004, December. Knowledge Management in Eco-tourism: A case study. In International Conference on Practical Aspects of Knowledge Management (pp. 508–521). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Kheiri, J & Nasihatkon, B, 2016. The effects of rural tourism on sustainable livelihoods (Case study: Lavij rural, Iran). Modern Applied Science 10(10), 10–22.

- Košić, K, Demirović, D & Dragin, A, 2017. Living in a rural tourism destination: The local community's perspective. Tourism in South East Europe 4, 267–278.

- Latip, NA, Rasoolimanesh, SM, Jaafar, M, Marzuki, A & Umar, MU, 2018. Indigenous participation in conservation and tourism development: A case of native people of Sabah, Malaysia. International Journal of Tourism Research 20(3), 400–409.

- Lew, A., & Cheer, J. (2018). Lessons Learned: Globalization, change, and resilience in tourism communities. In Lew JCaAA. (Ed.), Tourism, resilience, and sustainability: Adaptingto social, political and economic change, 319–323. London:Routledge.

- Li, W & Abiad, V, 1990. Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance.

- Lis, S, 2009. Impacts of tourism; An assignment about the development of tourism in Marjoca. In S Lis, Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany, pp.11 –14.

- Liu, S, Cheng, I & Cheung, L, 2017. The roles of formal and informal institutions in small tourism business development in rural areas of South China. Sustainability 9(7), 1–14.

- Markwick, MC, 2000. Golf tourism development, stakeholders, differing discourses and alternative agendas: the case of Malta. Tourism Management 21(5), 515–524.

- Marzuki, A & James, IHJ, 2012. Public participation shortcomings in tourism, planning: the case of the Langkawi Islands. Malaysia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(4), 585–602. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.638384

- Mason, P. 2015. Social change and the growth of tourism. In P. Mason (Ed.), Tourism impacts, planning and management (3rd ed.pp. 1–18, Vol. 13, ). Great Britain: Routhledge.

- Masud, MM, Aldakhil, AM, Nassani, AA & Azam, MN, 2017. Community-based ecotourism management for sustainable development of marine protected areas in Malaysia. Ocean & Coastal Management 136, 104–112.

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2018. Effects of the safari hunting tourism ban on rural livelihoods and wildlife conservation in Northern Botswana. South African Geographical Journal 100(1), 41–61.

- Mbaiwa, JE & Stronza, AL, 2010. The effects of tourism development on rural livelihoods in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 18(5), 635–656.

- McCabe, V, Poole, B, Weeks, P & Leiper, N, 2000. The business and management of conventions.

- Mitchell, M, & Hall, D, 2005. Rural tourism as sustainable business: Key themes and issues. Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business, 3-14.

- Moscardo, G, 2011. Exploring social representations of tourism planning: issues for governance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(4-5), 423–436. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.558625

- Ntuli, H & Muchapondwa, E, 2018. The role of institutions in community wildlife conservation in Zimbabwe. International Journal of the Commons 12(1), 134–169.

- Nyaupane, GP, & Poudel, S, 2011. Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Annals of tourism research, 38(4), 1344–1366.

- Ogra, M & Badola, R, 2014. Gender and climate change in the Indian Hindu-Kush Himalayas: global threats, local vulnerabilities. Earth System Dynamics Discussions 5(2): 1491–1520.

- Okello, MM, 2005. Land use changes and human–wildlife conflicts in the Amboseli area, Kenya. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 10(1), 19–28.

- Olson, J, 2014. Whose voices matter? Gender inequality in the United Nations framework Convention on Climate change. Agenda (durban, South Africa) 28(3), 184–187.

- Owuor, G, Knerr, B, Ochieng, J, Wambua, T & Magero, C, 2017. Community tourism and its role among agropastoralists in Laikipia County. Kenya. Tourism Economics 23(1), 229–236.

- Peerapun, W, 2018. Participatory planning approach to Urban conservation and Regeneration in Amphawa community, Thailand. Asian Journal of Environment-Behaviour Studies 3(6), 147–155. doi: 10.21834/aje-bs.v3i6.245

- Place, S, Hall, CM & Lew, A, 1998. Sustainable tourism: A geographical perspective.

- Pugh, J., & Potter, RB. (2018). Participatory planning in the Caribbean:some Key Themes. In Potter JPaRB. (Ed.), Participatory planning in the Caribbean; Lessons from Practice (pp. 1–23). London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Gruop.

- Putnam, RD, 2000. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. (pp. 223–234) In Culture and politics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rasoolimanesh, SM & Jaafar, M, 2016. Residents’ perception toward tourism development: a pre-development perspective. Journal of Place Management and Development 9(1), 91–104.

- Rasoolimanesh, SM, Ringle, CM, Jaafar, M & Ramayah, T, 2017. Urban vs. rural destinations: residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tourism Management 60, 147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.11.019

- Rate, S, Moutinho, L & Ballantyne, R, 2018. The New business environment AND trends in Touurism. In L Moutinho & A Vargas-Sanchez (Eds.), Strategic management in tourism. 3rd ed. CABI Tourism Texts., Boston, Masschusetts, 1 –15.

- Reid, H, 2001. Contractual national parks and the Makuleke community. Human Ecology 29(2), 135–155.

- Reid, H & Turner, S, 2004. The Richtersveld and Makuleke contractual parks in South Africa: Win-win for communities and conservation. London, UK: Earthscan.

- Saarinen, J, 2006. Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research 33(4), 1121–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.007

- Saarinen, J, 2007. Tourism in peripheries: The role of tourism in regional development in Northern Finland. Tourism in Peripheries: Perspectives from the Far North and South, 41-52.

- Saarinen, J, Rogerson, CM & Hall, CM, 2017. Geographies of tourism development and planning: tourism Geographies. An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment 19(3), 307–317. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2017.1307442

- Sachikonye, MT, Dalu, T, & Gunter, A, 2016. Sustainable livelihood principles and urban greening in informal settlements in practice: A case of Zandspruit informal settlement, South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 33(4), 518–531.

- Salafsky, N, & Wollenberg, E, 2000. Linking livelihoods and conservation: A conceptual framework and scale for assessing the integration of human needs and biodiversity. World development, 28(8), 1421–1438.

- Schnegg, M, 2018. Institutional multiplexity: social networks and community-based natural resource management. Sustainability Science 13(4), 1017–1030.

- Scoones, I, 1998. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Sussex, UK: Inst. Dev. Studies.

- Serrat, O, 2017. The sustainable livelihoods approach. In Knowledge solutions (pp. 21–26). Singapore: Springer.

- Shen, F, Hughey, KF, & Simmons, DG, 2008. Connecting the sustainable livelihoods approach and tourism: A review of the literature. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 15(1), 19–31.

- Sirima, A, & Backman, KF, 2013. Communities’ displacement from national park and tourism development in the Usangu Plains, Tanzania. Current Issues in Tourism 16(7-8), 719–735.

- Stone, MT & Nyaupane, GP, 2017. Protected areas, wildlife-based community tourism and community livelihoods dynamics: spiraling up and down of community capitals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26(2), 307–324. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1349774

- Stone, MT & Nyaupane, GP, 2018. Protected areas, wildlife-based community tourism and community livelihoods dynamics: spiraling up and down of community capitals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26(2), 307–324.

- Stuart, SN, Stuart, S, Adams, RJ & Jenkins, M, 1990. Biodiversity in sub-Saharan Africa and its islands: conservation, management, and sustainable use (Vol. 6). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Su, MM, Wall, G, & Jin, M, 2016. Island livelihoods: Tourism and fishing at long islands, Shandong Province, China. Ocean & Coastal Management, 122, 20–29.

- Su, M, Wall, G & Xu, K, 2016. Heritage tourism and livelihood sustainability of a resettled rural community: Mount Sanqingshan world heritage Site, Chin. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24(5), 735–757. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1085868

- Theobald, W, 2005. The meaning, scope, and measurement of travel and tourism. In T. William (Ed.), Global tourism (Vol. 10, pp. 5 - 24). Burlington, USA: Elsevier Publications.

- Thomas, A, 2004. Formal and Informal Institutions: Gender and Participationin the Panchayati Raj.

- Torniainen, TJ & Saastamoinen, OJ, 2007. Formal and informal institutions and their hierarchy in the regulation of the forest lease in Russia. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 80(5), 489–501.

- Tosun, C, 2002. Host perceptions of impacts: A comparative tourism study. Annals of Tourism Research 29(1), 231–253.

- Tosun, C, 2006. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27(3), 493–504.

- Tosun, C, & Jenkins, C.L, 1998. The evolution of tourism planning in Third-World countries: A critique. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(2), 101–114.

- Tosun, C & Timothy, DJ, 2001. Shortcomings in planning approaches to tourism development in developing countries: case of Turkey. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Managemen 13(7), 352–359. doi: 10.1108/09596110110403910

- Treves, A, Wallace, RB & White, AS, 2009. Participatory planning of interventions to Mitigate; human–wildlife conflicts. Conservation Biology 23(6), 1577–1587. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01242

- UNEP-WCMC, I, 2016. Protected planet report 2016. UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge UK and Gland, Switzerland, 78-95.

- UNEP (United Nations Environmental Programme), UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). 2005. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers. UNEP, Paris.

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organisation), 2015. Annual Report 2014. Madrid, Spain.

- UNWTO, 2007. Sustainable Tourism Indicators and Desitination Management Retrieved from Spain Madrid.

- UNWTO, 2018a. International tourism Trends 2017. Retrieved from Madrid, Spain.

- UNWTO, 2018b. International Tourist Arrivals Reach 1.4 billion Two Years Ahead of Forecasts (PR 19003). Retrieved from Madrid, Spain.

- Vatn, A, 2010. An institutional analysis of payments for environmental services. Ecological Economics 69(6), 1245–1252.

- Waligo, VM, Clarke, J & Hawkins, R, 2013. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tourism Management 36, 342–353.

- Williams, AM, & Hall, CM, 2002. Tourism, migration, circulation and mobility. In Tourism and migration (pp. 1–52). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Yanes, A, Zielinski, S, Diaz Cano, M & Kim, SI, 2019. Community-based tourism in developing countries: A framework for policy evaluation. Sustainability 11(9), 1–23.

- Zapata, MJ, Hall, CM, Lindo, P & Vanderschaeghe, M, 2011. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Current Issues in Tourism 14(8), 725–749.