ABSTRACT

Rural tourism contributes towards socio-economic development. In South Africa, rural areas experience significant development challenges with limited opportunities. Rural tourism as an instrumental tool against poverty requires rural tourism products to be not only viable but also sustainable. Presented is a sustainability assessment framework to assist South African enterprises to assess the sustainability of their rural tourism products (RTPs). The framework has two functions: it provides RTP operators with an understanding of all aspects of sustainability for which they are responsible and it provides indicators to measure the sustainability of the product. The indicators are presented as a sustainability scale that acts like a road map to enable operators to improve the sustainability of their RTPs in successive years. The intention and purpose of the framework is to ensure that sustainability is central to the operation of RTPs in South Africa thereby contributing toward sustainable development goals.

Introduction

Tourism is central to the growth of the South African economy (Phiri Citation2016; Amoah & Amoah Citation2019). Notwithstanding the prevailing tough economic climate, the president of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, in his 2019 State of the Nations Address, emphasised the tourism sector as a strategic area that has the ability to boost economic growth in the country (South African Government Citation2019). Whereas primary industries such as agriculture and mining used to be the dominant economic activities directed towards poverty reduction and alleviation, tourism is considered the new sunrise industry (Mtembu & Mutambara Citation2018). Statistics reveal that the tourism industry in South Africa contributed 1.5 million jobs and R425.8 billion to the economy in 2018, which represents 8.6 percent of all economic activity in the country (World Travel & Tourism Council Citation2018).

With the release of the Rural Tourism Strategy in 2012, the South African National Department of Tourism (NDT) committed to stimulating tourism growth and economic development within rural areas of the country. This strategy was influenced not only by the country’s National Development Plan (NDP), which calls for opportunities to grow rural development, but also by the fact that a quarter of South Africa’s population lives in rural areas characterised by extreme poverty and underdevelopment (NDT Citation2012a). Since rural areas in South Africa offer some of the most unique tourist destinations, including unspoilt wilderness, abundant wildlife, rugged coastlines, diverse and vibrant cultures, and distinctive heritage, there is much opportunity for rural tourism products (RTPs) to stimulate financial gains through much-needed jobs and also by creating and attracting investments in rural ways of life, traditions and local identities of rural areas (Bennett Citation2000; Mafunzwaini & Hugo Citation2005; Viljoen & Tlabel Citation2007; Trukhachev Citation2015; Mtembu & Mutambara Citation2018).

Tourism is recognised as a complex and multidimensional phenomenon mainly because the sector’s value chain transcends and influences the economics of other sectors, namely, agriculture, manufacturing, construction and transport (Adiyia & Vanneste Citation2018). Tourism in rural areas thus has the potential to provide new sources of economic benefit for local communities through its ability to contribute to economic diversification and local economic development by offering local employment opportunities, stimulating external investment in local economies and supplementing sectors traditionally dominant in rural areas (ILO Citation2019). While the positive economic and social impacts of tourism can contribute to local livelihoods, there are many negative impacts that can result due to the use of natural, cultural and heritage resources associated with rural areas that would have attracted tourists in the first place (Martin et al. Citation2017; Martínez et al. Citation2019; Nicolaides Citation2020).

Though tourism is not an extractive industry it is dependent on resources as it relies on natural resources, communities and the steady supply of products to create experiences for visitors (Ewert & Shultis Citation1997; Nicolaides Citation2020). As such, some of the most commonly reported impacts of rural tourism include the high concentration of people in sensitive ecosystems, insufficient or inadequate infrastructure or development plans to handle tourists, increase in waste production, increased use of limited resources and the displacement of cultures in desirable destinations (Ewert & Shultis Citation1997; Díaz & Rodríguez Citation2016; Martin et al. Citation2017; Kişi Citation2019; Martínez et al. Citation2019; Nicolaides Citation2020).

The South African tourism sector has its own unique challenges, including those related to sustainability. First, in South Africa, due to our specific socio-economic and political context, crime is often associated with the low income and high poverty levels. The South African crime rate and its resultant reputation often impact tourism as tourists fear xenophobia, mugging and violent assault (Adeleke et al. Citation2008). Second, South Africa is a water scarce country and some of its most popular tourism destinations, such as the Western, Eastern and Northern Cape provinces, periodically experience severe drought (Colvin Citation2016). In addition, the vulnerable and volatile electricity supply system often leaves tourists in darkness and tourism operators at a loss (Duminy Citation2019). The electricity and water shortages are forcing tourism enterprises to invest in electricity and water supply for their guests, often at great personal expense. Third, in South Africa landfill space is very limited and waste management is thus critical, especially considering that larger numbers of tourists equate to greater generation of waste. Dreyer et al. (Citation2016), for example, note that waste generation in the hospitality industry has a severe impact on the environment because the establishments within this sector, such as hotels, use large quantities of consumer goods as part of their operations. Lastly, recent health-related issues such as the listeriosis outbreak in South Africa and the global COVID-19 pandemic have affected tourism because tourists are worried about health and safety standards in the country. There is thus a need to minimise the negative physical and social effects of tourism, specifically rural tourism. It is necessary to establish a balance between the concentration and requirements of tourists, the RTP, the fragility and sensitivity of the environment and the local community while continuing to build the economic stability of the product offering (Marzo-Navarro et al. Citation2015; Khartishvili et al. Citation2019; Martínez et al. Citation2019).

Earmarking rural tourism as a tool in the fight against poverty requires that RTP services and/or activities be not only viable but also sustainable. This is firmly reinforced in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Its importance as a driver of job creation and local economic development is reflected in its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), 12 (responsible consumption and production) and 14 (life below water). These three SDGs include tourism-specific targets (ILO Citation2019). Target 12b of SDG 12 requires all countries to develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts to ensure a form of tourism that creates jobs and promotes local cultures and products. South Africa has some way to go before achieving the targets of SDG 12 as the country does not have sustainability guidance or performance measures specific to RTP services and/or activities even if it does have a national standard on responsible tourism (SANS 1162).

Despite much research into the issue, the practical application of sustainability measurement in tourism is still not widespread in the management of tourist destinations. In this paper we present a sustainability framework that was designed to assist RTPs in South Africa to assess and plan for sustainability. Since sustainability is about ensuring effective functioning of interconnected social and ecological systems, it is vital to ensure that a sustainability framework addresses a multitude of relationships and interactions within the greater social ecological system within which an RTP operates. This requires that sustainability assessments and monitoring apply a holistic systems thinking approach. The intention and purpose of the sustainability framework is to ensure that sustainability is central to the operation of RTPs in South Africa. The framework offers sustainability objectives for the RTPs to meet and scaling indicators that will enable RTPs to measure their performance in terms of their optimal use of environmental resources, the social and cultural authenticity of their product and the provision of economic benefits for the local community.

Rural tourism

Rural tourism has produced a plethora of definitions in the extant literature (Lane & Kastenholz Citation2015; Amoah & Amoah Citation2019; Mtapuri & Giampiccoli Citation2019). In general, rural areas are associated with characteristics such as agriculture, low population density and small, widely scattered settlements (Lenao & Saarinen Citation2015). Pearce (Citation1989) defines rural tourism as a country experience that encompasses a wide range of attractions taking place in natural and/or agricultural milieu. Lane (Citation1994) posits that rural tourism is located in rural areas and its functionality is predominantly limited to non-urban spaces. Fleischer and Pizam (Citation1997) relate rural tourism to ‘country vacations’, during which tourists spend most of their time engaging in recreational activities in a rural environment. Petric (Citation2003) adds to this definition by inferring that visitors have personal contact with, or a taste of, the physical and environmental countryside. Fatimah (Citation2015) emphasises the component of culture in the definition of rural tourism, including historical places and religious views. Ultimately, there are several catchwords that emerge from these various definitions, including ‘country experience’, ‘cultural and/or natural resources’, ‘farm or agricultural activities, ‘heritage’ and ‘traditional practices’. Rural tourism is, therefore, an umbrella definition capturing terminology such as: ecotourism, which is focused around the natural environment; agrotourism, which allows tourists to participate in traditional agricultural practices; cultural tourism, which enables tourists to experience the places and activities that signify both the history and heritage of local people; community-based tourism, which enables tourists to immerse themselves and experience village life; and adventure tourism, which involves action-based activities for tourists (Martínez et al. Citation2019; Lwoga & Maturo Citation2020).

The potential to stimulate social and economic benefits in rural areas results from the fact the tourist attractions, be they natural, cultural or historical, are already in place (Jacobs et al. Citation2020). This makes the level of investment required by rural tourism entrepreneurs to attract tourists relatively low (Ibănescu et al. Citation2018). Investment by tourism entrepreneurs, government or private sector investors is, however, required in order to establish RTPs. Once this investment is in place, the significance of rural tourism lies in its potential to change and upgrade the lives of communities through the RTPs in the area. Employment made possible by RTPs contributes to population retention in rural communities by encouraging youths, who are most vulnerable to emigrating to urban areas, to stay. Rural tourism through RTPs should (1) revive and diversify local incomes, employment and growth; (2) contribute to the cost of providing economic and social infrastructure; (3) encourage the development of other industrial sectors (e.g. through local purchasing links); (4) contribute to local residents’ amenities and services; (5) provide skills development for the unskilled, youths, women and emerging entrepreneurs; and (6) contribute to the conservation of environmental and cultural resources (Rogerson Citation2012; Jacobs et al. Citation2020; Lwoga & Maturo Citation2020). These rural tourism goals are almost identical to those of sustainable tourism development (Lane & Kastenholz Citation2015).

Sustainability in tourism

The Brundtland Commission report of 1987 established the fundamental definition of sustainable development, namely, development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs too (World Commission on Environment and Development Citation1987). This definition connects economic development, environmental protection and social equity. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) adapted this definition to tourism and now defines sustainable tourism thus:

[It] makes optimal use of environmental resources; respects the socio-cultural authenticity of host communities; ensures viable, long-term economic operations, providing socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders; requires the informed participation of all relevant stakeholders, as well as strong political leadership; and also maintains a high level of tourist satisfaction. (UNEP and UNWTO Citation2005)

While a number of different terminologies are synonymous with sustainable tourism, such as ‘responsible tourism’ and ‘ethical tourism’, they all embrace the key parameters of sustainability within the tourism sector, including: establishing viable, long-term economic operations; providing socio-economic benefits such as employment; providing social services to communities; contributing to poverty alleviation; and reducing the negative impact on the receiving environment (UNWTO Citation2004; Díaz & Rodríguez Citation2016). Globally, these have been tackled in terms of policy and physical implementation, including reducing the carbon footprint of transport, reducing tourist overcrowding, using alternative energy options, pursing sustainability certifications, sourcing products locally and managing waste reduction sustainably, to name a few.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with its 17 SDGs, establishes the new global development pathway. As the tourism sector comprises an interconnected system involving the tourism destination, the tourism business/product, the tourist and the local community, as well as interlinkages with many other economic sectors, tourism can accelerate progress towards achieving all 17 SDGs () (UNWTO & UNDP Citation2017; UNWTO & OSA Citation2018). The SDGs, therefore, represent a new culture of sustainability for the sector. As part of the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development (IY2017), the UNWTO defined five pillars that specifically link the concept of sustainable tourism with the 2030 Agenda. These pillars represent the areas within which tourism is able to make a significant contribution to sustainability. These five pillars are: (1) sustainable economic growth, (2) social inclusiveness, employment and poverty reduction, (3) resource efficiency, environmental protection and poverty reduction, (4) cultural values, diversity and heritage; and (5) mutual understanding, peace and security (UNWTO Citation2018). The relationship of these pillars with the individual SDGs in presented in .

Table 1. The SDGs, their relationship with tourism and the sustainability pillars to which tourism can make a contribution.

Sustainability of rural tourism

While tourism is considered a key sector in terms of meeting the SDGs, sustainable tourism has specific application to rural tourism as its point of departure is strongly grounded in the rural development plans of developing countries, namely: (1) the creation of local income, employment and growth; (2) the contribution to economic and social infrastructure; (4) the contribution to local resident amenities and services; and (5) the contribution to the conservation of environmental and cultural resources (Saarinen Citation2014; Lenao & Saarinen Citation2015; Mtembu & Mutambara Citation2018). In South Africa, for example, some of the main development challenges experienced in rural areas include: unsustainable use of natural resources, inadequate access to socio-economic and cultural infrastructure and services, lack of access to water for both households and agricultural development, low literacy rates and skill levels, migratory labour practices, decay of the social fabric and abundance of unexploited opportunities in many economic sectors (Department of Rural Development and Land Reform Citation2010; Mtembu & Mutambara Citation2018). Rural tourism, therefore, is ideally placed to not only embrace the objectives of sustainable tourism but also, and more so, to help overcome rural development challenges in a sustainable manner.

The significance of rural tourism lies in its potential to change and uplift the lives of those in rural communities through contributing to the reduction of poverty (Amoah & Amoah Citation2019). Sustainability is integral to long-term community well-being (Amoah & Amoah Citation2019). In a rural context, sustainability is about ensuring that the social ecologicall system in which the RTP operates is able to maintain functionality and a workable structure to the extent that communities are able to exist and continuously adapt within their social and ecological boundaries and thresholds (Young et al. Citation2006; Collier et al. Citation2009; Pisano Citation2012; Xu et al. Citation2015). Economically, local communities can benefit by becoming involved in tourism through the creation of RTPs that provide a variety of hospitality services, markets local products and creates favourable conditions in terms of additional income generation (Mrkša & Gajić Citation2014). The social component reflects an improved quality of life for those living within a rural area. This can occur through the improvement and construction of infrastructure, raising awareness of and knowledge about the potential of an area and maintaining its cultural heritage and characteristics (Mrkša & Gajić Citation2014; Marzo-Navarro et al. Citation2015). Maintaining and protecting ecological integrity and ecosystem services is vital. All RTPs must respect the ecological capacity of the social ecological system in which they operate and reduce their impact on the environment at all times (Mrkša & Gajić Citation2014). As such, a systematic approach is needed in sustainable tourism development planning (Kişi Citation2019).

Responsible and sustainable rural tourism in South Africa

Sustainable tourism is not new to South Africa. In fact, the Tourism Act (Act 3 of 2014) embraces sustainability through the concept of ‘responsible tourism’. Section 2(2) of the Act emphasises that tourism must seek to avoid negative economic, environmental and social impacts. The concept of rural tourism as a mechanism to generate economic benefits for local people, enhance the well-being of host communities and improve working conditions is also incorporated in responsible tourism. Following the promulgation of this Act, the NDT commissioned the National Responsible Tourism Development Guidelines for South Africa (2002). These guidelines have been instrumental in highlighting the importance of developing tourism with ‘dignity, respect and nurture of local cultures’, promoting equality in terms of gender, ethnicity, age and disability, as well as the implementation of national labour standards. The South African National Minimum Standard for Responsible Tourism (SANMSRT) is designed to complement the guidelines. The SANMSRT aims to establish a common understanding of responsible tourism and to harmonise the different sets of criteria that were previously used for certifying the sustainability of tourism businesses (ILO Citation2019). The Rural Tourism Strategy also embraces sustainability as the unlinking principle for this form of tourism. The contemporary legislative interventions in South Africa are progressive because they set out to address inequality in tourism enterprises by forging sustainability in terms of environmental protection and inclusiveness whereby the previously disadvantaged have leverage to enter and effectively participate in this thriving sector. What has been lacking, however, is any form of measuring and monitoring of sustainability.

Sustainability assessment tools for tourism

Two sustainability assessment tools stand out as significant in relation to tourism, namely, the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). The TBL is one of the first tools designed to expand organisational performance evaluation to include not only the financial bottom line of an organisation but also non-financial elements relating to contributions to environmental quality and social justice (Elkington Citation1999). The GRI was later developed as a reporting framework providing insight into how and what to report and measure in terms of the TBL. While the framework is applicable to all forms of business, the GRI has developed sector-specific supplements and currently does not cover the tourism and hospitality industry.

Research also shows that there is no universally accepted method for measuring the sustainability of tourism products (Parris & Kates Citation2003; Worrall et al. Citation2009; Weber & Taufer Citation2016). What is common amongst the wide range of tools that currently exist is an acknowledgement that, if tourism products are to be sustainable, the current status of their portfolios, including their strengths and weaknesses, must be made known (Weber & Taufer Citation2016).

The International Institute of Sustainable Development’s Bellagio Sustainability Assessment and Measurement Principles (STAMP) provide an excellent platform from which to develop guidance for the development of sustainability assessment frameworks (Pinter et al. Citation2012). The Bellagio STAMP emphasises the need for any sustainability assessment to: (1) have a guiding vision in terms of its objective to measure sustainability; (2) ensure that the assessment takes all aspects of sustainability into consideration; (3) have adequate spatial and temporal scope; (5) gather reliable and accessible data with which to measure and monitor sustainability; (6) be transparent; (7) ensure effective communication of the sustainability results; (7) ensure broad participation; and (8) provide continuity.

The most common and effective means of measuring sustainability is via indicators. Indicators need to be identified in such a way that they are not only able to measure a specific parameter but also serve to manage the development of a particular activity and, thereby, to guide the tourism operation towards sustainability (Torres-Delgado & Saarinen Citation2014). Ultimately, the indicators and the manner in which they are used in an assessment must be able to identify the key factors of change, their evolution and potential threats (James Citation2004). What is not measured can neither be managed nor improved. So, to make a case of whether or not RTPs are sustainable, it is crucial that we must have principles, criteria and indicators to be used as measurements.

Methodology

Taking the Bellagio STAMP into consideration, in order to develop a sustainability framework for RTPs in South Africa we made use of the Principle, Criteria and Indicator (PCI) approach. The PCI approach was originally developed for assessing sustainability in forestry (van Bueren & Blom Citation1997). The PCI approach has subsequently been used in a variety of studies, for example: the measurement of changes taking place to develop organic farming (Darnhofer et al. Citation2010); the management of the reuse of mining land (Worrall et al. Citation2009); and the participatory design of indicators for local coastal management (Fontalvo-Herazo et al. Citation2007). The PCI approach is distinctive because it is a hierarchical framework that makes it possible to disaggregate the complex concept of sustainability into assessable and communicable components. The ‘principles’ are the fundamental desired outcomes for a sustainable RTP, the ‘criteria’ are the conditions or objectives that the RTP needs to meet in order to reach the desired sustainable outcome, and the ‘indicators’ are the measurable states that allow the RTP to assess its progress toward a sustainable operation.

To define the sustainability principles that make up our sustainability framework for RTPs in South Africa, the team undertook two main tasks. First, we carried out a literature review (including international literature) in which all sustainability aspects relating to responsible tourism were defined. Based on the objectives of South Africa’s National Development Plan, Rural Development Programme, the National Tourism Sector Strategy and the Rural Tourism Strategy, principles were refined in a way that encapsulates both global standards and the specific needs of the country.

Second, based on these principles, the project team engaged in a participatory process. Three workshops were held with various tourism stakeholders. The purpose behind the workshops was to refine the principles and define the criteria and indicators specific to those principles and in line with the development objectives of the country. The workshops included a number of different stakeholders, most notably officials from the National Department of Tourism (DoT), municipality officials dealing specifically with tourism and RTP owners. Recruitment for participation in the workshops took the form of purposeful sampling. Used widely in qualitative research, purposeful sampling is a non-random selection of participants based on purpose and research question (Palinkas et al. Citation2015). Since this research was part of the DoT research programme, the workshop participants were identified in conjunction with the DoT specifically based on their interest in, experience and knowledge of the topic. The workshops were as follows:

Workshop with DoT officials that deal with sustainability issues: June 2017

Training workshop with tourism stakeholders, including government officials, students and RTP owners: March 2018

Capacitation workshop held as a component of the 2018 ITSA conference; provincial tourism offices attended: August 2018

The defined criteria were cross-referenced with other tourism sustainability assessment tools and international sustainability tools such as the GRI. The indicators were developed accordingly and then tested with tourism stakeholders, including RTPs and government officials, during workshops.

Whilst attending a workshop, one RTP owner was selected and the framework was subjected to the owner’s self-assessment. We present the outcome of this exercise, as a case study, in the results section to show the applicability of the framework.

The sustainability framework

The sustainability assessment framework that was designed based on the PCI approach comprises six principles, 22 criteria and 28 indicators. The six principles address the three pillars of sustainability, namely, economic, social and environmental considerations, which all RTPs should be addressing. The principles include sustainability management of the RTP, economic viability of the RTP, RTP satisfaction, socio-cultural authenticity, community beneficiation and well-being and optimal use of resources.

The six principles are thus:

Sustainability management: This principle embraces the non-economic aspects of the business. It relates to the planning, organising, leading and controlling of tourism activities, services and/or activities while at the same time sustaining the social, economic and natural environment upon which the economy and society depend.

Economic viability: This principle is about ensuring and maintaining the long-term financial viability of the RTP. Tourism products should be financially profitable while also having a positive impact on society and the environment.

RTP satisfaction: This principle is concerned with the needs of the guest and meeting those needs. Ii investigates how tourism activities and/services supplied by an RTP meet or surpass tourists’ expectations. It provides RTP owners with a metric that they can use to manage and improve their offering.

Socio-cultural authenticity: This principle refers to the conservation of cultural heritage and traditional values in the area in which the RTP operates. The extent to which a tourism product reflects the beliefs, values, culture and heritage and depicts an accurate detail of the everyday life and experience of a specific community surrounding the RTP is extremely important for such a tourism product.

Community beneficiation and well-being: This principle applies to building strong links between the RTP and the community. The tourism product should give access to decent ownership and work opportunities for the locals, particularly youth, women and people with disabilities, and be a tool for the empowerment of these vulnerable groups, helping to ensure their full participation in all aspects of society.

Optimal use of resources: This principle concerns the RTP operating within environmental limits. Tourism products have the moral and commercial imperative to use resources efficiently and to conserve and preserve fragile ecosystems.

These RTP sustainability principles are interconnected, highlighting that the performance of the RTP in terms of one principle has an effect on another principle. The framework was specifically designed in this manner so that the sustainability of an RTP is measured as a function of the system as a whole. In this regard, an RTP is responsible for contributing to the resilience of the social ecological system in which it operates, resilience being the ability of a system to maintain its structure and function. depicts the interconnected relationships between the RTP sustainability principles discussed above. The figure illustrates that the management of an RTP in terms of service provision is linked to the economic viability of the business; both principles are significantly influenced by RTP satisfaction. RTP management contributes to the socio-cultural authenticity of the RTP operation as well as its operational impact on natural resources. Both of these principles also influence RTP satisfaction. The economic return of the RTP will significantly contribute to the well-being of the community in terms of job creation and skills development.

provides the criteria and indicators associated with the six principles.

Table 2. Principles, criteria and indicators to assess the sustainability of RTPs in South Africa.

Based on the PCI presented above, an easy-to-use framework was developed that is threefold in its purpose and intent. First, it provides RTPs with an understanding of the aspects of sustainability for which they need to be responsible. This is especially important if this is the first time an RTP is addressing sustainability in its operations. For example, the principles and criteria provide the RTP with the sustainability conditions needed to address and measure its operations. Second, the framework provides indicators. Having indicators enables the RTP to measure its sustainability performance. Third, associated with each indicator is a sustainability scale to enable the RTP to measure its performance against each criterion within each principle. This scale () was devised based on a Likert scale. Such a scale is important as it enables quantitative values to be determined for any kind of subjective or objective dimension. A five-point scale was chosen such that varying degrees of sustainability (positive) or unsustainability (negative) could be determined. Each weighting represents a measure that relates to an RTP’s level of performance; e.g. 1 = unacceptable, 3 = acceptable and 5 = excellent. In this regard, we designed each indicator to have a weighting based on the sustainability scale. Another important aspect of this sustainability scale is that it can serve as a roadmap providing the RTP with the relevant information it needs to improve on its sustainability performance in future.

Table 3. Sustainability scale to access performance of RTPs in South Africa.

Application of the framework: A case study of an RTP operator located in eThekwini Municipality

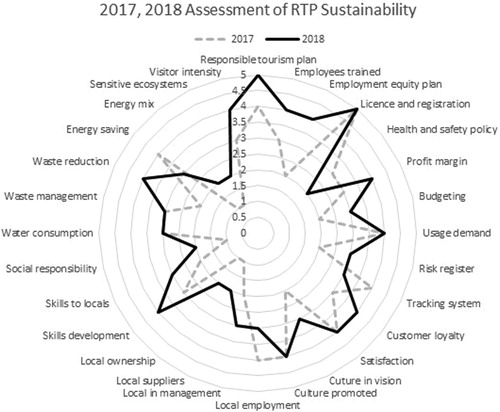

In order to analyse application of the framework, a self-assessment was conducted by an RTP owner who then provided feedback to the team. The RTP is a small bed and breakfast (B&B) situated in Tongaat Beach, approximately 35 kilometres from Durban. While Tongaat Beach may be considered a small town, the B&B is situated on the outskirts very close to the sugar plantations. Scores were given for the reporting year of 2017 and some of 2018 (). The result of this exercise was then mapped on a spider diagram (), which provides a graphical representation of the sustainability performance of the RTP over those two years. Comparisons over that two-year period enable the RTP to identify whether or not it has improved in terms of sustainability.

Table 4. Theoretical example of a sustainability assessment of an RTP over a two-year period, highlighting performance.

The spider diagram presents a visual representation of the RTP’s performance in relation to the six principles. It shows that, whereas the RTP’s satisfaction has remained relatively stable over a period of 12 months, a visible improvement can be seen in relation to the other principles. Moreover, the diagram provides an overall summary in the form of a snapshot that allows the user to gain a visual perspective of the sustainability performance of the RTP across all six principles.

Numerous benefits are associated with the use of a sustainability roadmap and assessment framework. In the case of RTPs, these benefits include:

Early identification of emerging issues

Identification and reduction of impacts

Focused decision making to lower risks or costs

Product marketing and brand building

Optimal and sustainable use of resources

Well-being of host communities and cultural/heritage

Monitoring that leads to opportunities to make improvements

Conclusion

Rural tourism products have the potential to contribute significantly to socio-economic development in South Africa. They are predominantly associated with South Africa’s rich and diverse cultural and natural landscapes. The management, or lack thereof, of RTPs has the potential to affect the condition of rural areas, including the well-being of communities, cultural inheritance and traditional activities and the physical environment. Informed decisions, good planning and management can ensure that RTPs make a positive contribution to sustainable development in rural areas.

In this paper, we presented a sustainability assessment framework that has multiple functions. It not only informs RTP owners of the sustainability aspects they need to consider in their operations but also enables the operators to measure their sustainability performance against indicators. Since the framework makes use of a sustainability scale with indicators presented for each level, RTP operators are able to use it as a roadmap to further improve their sustainability so that their RTP:

Contributes to the optimal and most sustainable use of natural and cultural resources

Respects the social and cultural authenticity of rural areas

Provides economic benefits to stakeholders who have a direct and indirect relationship with the RTP

RTP operators are, therefore, encouraged to use this framework first as a tool to determine their sustainability. As sustainability becomes more entrenched in their operations, the operators are then encouraged to build and adapt the tool so that they can address more complex aspects associated with sustainability and tourism. This framework is aligned with meeting the development and growth goals of South Africa’s National Development Plan as well as its contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adeleke, BO, Omitola, AA & Olukole, OT, 2008. Impacts of xenophobia attacks on tourism. IFE Psychologia 16(2), 136–147.

- Adiyia, B & Vanneste, D, 2018. Local tourism value chain linkages as pro-poor tools for regional development in Western Uganda. Development Southern Africa 35(2), 210–224.

- Amoah, F & Amoah, LNA, 2019. Tourist experience, satisfaction and behavioural intentions of rural tourism destinations in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 8(4), 1–12.

- Bennett, JA, 2000. Managing tourism services. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

- Collier, WM, Jacobs, KR, Saxena, A, Baker-Gallegos, J, Carroll, M & Yohe, GW, 2009. Strengthening socio-ecological resilience through disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation: Identifying gaps in an uncertain world. Environmental Hazards 8(3), 171–186.

- Colvin, C, 2016. Foreword, in WWF-SA, Water: Facts & futures. http://awsassets.wwf.org.za/downloads/wwf009_waterfactsandfutures_report_web__lowres_.pdf Accessed May 2020.

- Darnhofer, I, Lindenthal T, Bartel-Kratochvil R & Zollitsch W, 2010. Conventionalisation of organic farming practices: from structural criteria towards an assessment based on organic principles. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 30(1), 67–81.

- Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, 2010. South Africa position paper on rural development. A model for the comprehensive rural development programme. http://www.rimisp.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Paper_T.T_Gwanya.pdf Accessed July 2019.

- Díaz, MR, & Rodríguez, TFE, 2016. Determining the sustainability factors and performance of a tourism destination from the stakeholders’ perspective. Sustainability 8(9), 951.

- Dreyer RPR, du Plessis R & Mearns, KF, 2016. Waste characterisation and review of the waste management practices at Phinda Private Game Reserve (KZN). Proceedings of the 23rd WasteCon Conference, 17–21 October 2016, Emperors Palace, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Duminy, E, 2019. Load shedding and its effect on SA’s tourism industry. https://www.bizcommunity.com/PDF/PDF.aspx?l=196&c=373&ct=1&ci=198962 Accessed May 2020.

- Elkington, J, 1999. Triple bottom line revolution—reporting for the third millennium. Australian CPA 69(1), 75–77.

- Ewert, A, & Shultis, J, 1997. Resource-based tourism: An emerging trend in tourism. Parks and Recreation 32(9), 94–104.

- Fatimah, T, 2015. The impacts of rural tourism initiatives on cultural landscape sustainability in Borobudur area. Procedia Environmental Sciences 28(2015), 567–577.

- Fleischer, A, & Pizam, A, 1997. Rural tourism in Israel. Tourism Management 18(6), 367–372.

- Fontalvo-Herazo ML, Glaser M & Lobato-Ribeiro A, 2007. A method for the participatory design of an indicator system as a tool for local coastal management. Ocean & Coastal Management 50(10), 779–795.

- Ibănescu, BC, Stoleriu, OM, Munteanu, A & Iațu, C, 2018. The impact of tourism on sustainable development of rural areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 10, 3529.

- ILO. 2019. Sustainable tourism – A catalyst for inclusive socio-economic development and poverty reduction in rural area. Accessed May 2020. file:///D:/Current%20projects/Tourism/Literature/ILO%20responsible%20tourism.pdf.

- Jacobs, L, Du Preez, EA & Fairer-Wessels F. 2020. To wish upon a star: Exploring astro tourism as vehicle for sustainable rural development. Development Southern Africa 37(1), 87–104.

- James, D. 2004. Local sustainable tourism indicator. Estudios Tuŕısticos 161–162, 219–232.

- Khartishvili, L, Muhar, A, Dax, T, & Khelashvili, I. 2019. Rural tourism in Georgia in transition: Challenges for regional sustainability. Sustainability 11(2), 410.

- Kişi, N. 2019. A strategic approach to sustainable tourism development using the A’WOT hybrid method: A case study of Zonguldak, Turkey. Sustainability 11(4), 964.

- Lane, B, 1994. What is Rural Tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2(1 & 2), 7–21.

- Lane, B & Kastenholz, E, 2015. Rural tourism; the evolution of practice and research – towards a new generation concept? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 23(8–9), 1133–1156.

- Lenao, M & Saarinen, J, 2015. Integrated rural tourism as a tool for community tourism development: exploring culture and heritage projects in the North-East District of Botswana. South African Geographical Journal 97(2), 203–216.

- Lwoga, NB & Maturo, E, 2020. Motivation-based segmentation of rural tourism market in African villages. Development Southern Africa. Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2020.1760791

- Mafunzwaini, AE & Hugo, L, 2005. Unlocking the rural tourism potential of the Limpopo province of South Africa: Some strategic guidelines, Development Southern Africa 22(2), 251–265.

- Martin, JMM, Fernández, JAS, Martin, JAR & Aguilera, JdDJ, 2017. Assessment of the Tourism’s potential as a sustainable development instrument in terms of annual stability: Application to Spanish rural destinations in process of consolidation. Sustainability 9(10), 1692.

- Martínez, JMG, Martín, JMM, Fernández, JAS & Mogorron-Guerrero, H, 2019. An analysis of the stability of rural tourism as a desired condition for sustainable tourism. Journal of Business Research 100, 165–174.

- Marzo-Navarro, M, Pedraja-Iglesias, M & Vinzón, L, 2015. Sustainability indicators of rural tourism from the perspective of the residents. Tourism Geographies 17(4), 586–602.

- Mrkša, M & Gajić, T, 2014. Opportunities for sustainable development of rural tourism in the municipality of Vrbas. Economics of Agriculture 61(1), 163–175.

- Mtapuri, O & Giampiccoli, A, 2019. Tourism, community-based tourism and ecotourism: A definitional problematic. South African Geographical Journal 101(1), 22–35.

- Mtembu, B & Mutambara, E, 2018. Rural tourism as a mechanism for poverty alleviation in Kwa-Zulu-Natal Province of South Africa: Case of Bergville. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 7(4), 1–22.

- National Department of Tourism (NDT), 2012a. Rural tourism strategy. Pretoria: Republic of South Africa.

- National Department of Tourism (NDT), 2012b. National tourism sector strategy (NDT). https://www.tourism.gov.za/AboutNDT/Branches1/Knowledge/Documents/National%20Tourism%20Sector%20Strategy.pdf Accessed June 2017.

- Nicolaides, A, 2020. Sustainable ethical tourism (SET) and rural community involvement. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 9(1), 1–16.

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N & Hoagwood K, 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42(5): 533–544.

- Parris, TM & Kates, RW, 2003. Characterizing and measuring sustainable development. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 28, 559–86.

- Pisano, U, 2012. Resilience and sustainable development: Theory of resilience, systems thinking and adaptive governance. ESDN Quartely Report N26. Vienna, Austria: European Sustainable Development Network. https://www.sd-network.eu/?k=resources Accessed July 2018.

- Pearce, DG, 1989. Social impacts of tourism. Social Cultural and Environmental Impacts of Tourism, NSW Tourism Commission, Sydney. 1–39.

- Petric, L, 2003. Constraints and possibilities of the rural tourism development with special stress on the case of Croatia. Jyvaskyla, Finland: University of Jyvaskyla.

- Phiri, A, 2016. Tourism and Economic Growth in South Africa: Evidence from linear and nonlinear cointegration frameworks. Managing Global Transitions 14(1), 31–53.

- Pinter, L, Hardi, P, Martnuzzi, A & Hall, J, 2012. Bellagio STAMP: Principles for sustainability assessment and measurement. Ecological Indicators 17, 20–28.

- Rogerson, CM, 2012. The tourism-development nexus in sub-Saharan Africa: Progress and prospects. Africa Insight 42(2), 28–45.

- Saarinen, J, 2014. Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability, 6(11), 1–17.

- South African Government, 2019. President Cyril Ramaphosa: State of the nation address 2019. http://www.gove.za/speeches/2SONA2019 Accessed May 2020.

- Torres-Delgado, A & Saarinen, J, 2014. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tourism Geographies 16(1), 31–47.

- Trukhachev, A, 2015. Methodology for evaluating the rural tourism potentials: A tool to ensure sustainable development of rural settlements. Sustainability 7(3), 3052–3070.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) & United Nations World Tourism (UNWTO), 2005. Making tourism more sustainable. A guide for policy makers. United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organization. http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/pdf/DTIx0592xPA-TourismPolicyEN.pdf Accessed September 2017.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2004. Sustainable development of tourism conceptual definition. Madrid: United Nations World Tourism Organization.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2017. Tourism and the sustainable development goals – Journey to 2030. Madrid: UNWTO. Accessed April 2020. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Sustainable%20Development/UNWTO_UNDP_Tourism%20and%20the%20SDGs.pdf.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2018. Tourism for development. Volume 1: Key areas for action. Madrid: UNWTO. Accessed May 2020. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284419722

- United Nations World Tourism Organization and Organization of American States, 2018. Tourism and the sustainable development goals – Good practices in the Americas. Madrid: UNWTO.

- van Bueren, L & Blom, EM, 1997. Principles, criteria, indicators. Hierarchical framework for the formulation of sustainable forest management standards. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Tropenbos Foundation.

- Viljoen, J., & Tlabel, K, 2007. Rural tourism development in South Africa: Trends and challenges: Human sciences research council of South Africa: Cape Town.

- Weber, F & Taufer, B, 2016. Assessing the sustainability of tourism products – as simple as it gets. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 11(3), 325–333.

- World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987. Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- World Travel and Tourism Council, 2018. Travel and tourism economic impact 2018 South Africa. https://www.bbrief.co.za/content/uploads/2019/11/WTTC’s-economic-report.pdf Accessed July 2018.

- Worrall, R, Neil, D, Brereton, D & Mulligan, D, 2009. Towards a sustainability criteria and indicators framework for legacy mine land. Journal of Cleaner Production 17(2009), 1426–1434.

- Xu L, Marinova D & Guo X, 2015. Resilience thinking: A renewed system approach for sustainability science. Sustainability Science 10(1), 123–138.

- Young OR, Berkhout F, Gallopin GC, Janssen MA, Ostrom E & Van Der Leeuw S, 2006. The globalization of socio-ecological systems: An agenda for scientific research. Global Environmental Change 16(3), 304–316.