ABSTRACT

This study develops and tests a structural model that incorporates the determinants of SME financial performance in Mauritius. Data were collected from 384 tourism SME owners using a structured questionnaire. The results indicate that managerial capability has a significant positive effect on SME performance and is in turn influenced by managers’ autonomy and competence. The study does find a significant relationship between innovation capability and SME performance. Given the socio-economic importance of SMEs to the Mauritian economy, the results provide crucial information to government and policy-makers that can used to develop macro-economic policies that increase their contribution to the socio-economic development of the country. For entrepreneurs, the study provides insights on areas of interventions that can lead to an improvement in the financial performance of their organisations. Despite the study limitations, it contributes to a theoretical understanding of the determinants of financial performance in African economies.

1. Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are important for economic growth and contribute to tourism development in an economy (Rogerson Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2005, Citation2006, Citation2008; Pillay & Rogerson Citation2013). They are formed out of existing opportunities and help in satisfying tourism demand and filling the production gaps in the market. For developing countries, SMEs hold particular prominence as they help nurture a culture of entrepreneurship (Kirsten & Rogerson Citation2002; Huarng & Hui-Kuang Yu Citation2011). The promotion of entrepreneurial attitude and abilities is also believed to make a positive contribution to poverty reduction. Furthermore, SMEs help reinforce industrial relationships and make use of resources productively and efficiently (Rogerson Citation2007, Citation2012). These factors together allow the country to be less reliant on overseas help (Peberdy & Rogerson Citation2000; Todaro & Smith Citation2012). Thus, the development of SMEs in a country and economic growth is deeply intertwined (Rogerson Citation2010). However, in developing countries, SMEs often struggle to sustain, especially during constantly fluctuating economic conditions. Furthermore, the future of an SME relies largely on the entrepreneur. All important decisions, including setting the business direction, its long term strategy, its tactical choices to reach the set destination are all made by that individual (Masurel & Nijkamp Citation2004). The quality of those decisions often depends on several factors and individual traits of the entrepreneur including technical know-how, past experiences and education level (Onkelinx et al. Citation2016).

Various studies have been carried out by researchers and policy-makers alike on the determinants of the financial performance of SMEs (Kober et al. Citation2012; Saunila et al. Citation2014; Ogunyomi & Bruning Citation2016). However, most of those studies have been carried out in developed economies and those outside the African region. The latter’s specific socio-economic and political characteristics that influence SME development are different from those of industrialised countries (Rogerson Citation2000; Visser & Rogerson Citation2004; Rogerson & Rogerson Citation2011). Like in several other African countries, SMEs make an important contribution to the economic development of Mauritius. For example, the share of SMEs in gross domestic product and total employment is currently estimated to be around 40% and 54% respectively. The ten-year master plan for the SME sector in Mauritius aims at increasing SME’s contribution to gross domestic product and total employment to 52% and 64% respectively (Ministry of Business, Enterprise and Cooperatives, Citation2017). Most SMEs operate in tourism and related sectors such as accommodation, tour operations, entertainment, ground transportation, and food services. However, despite their current and anticipated economic contribution to the Mauritian economy, research on this sector is clearing lacking and little is known about their financial performance and its determinants. At present, policies to support SMEs seem to be implemented on an ad-hoc basis, without a proper understanding of the factors influencing their financial performance. In an attempt to contribute to the very limited research on SME performance in Mauritius, this study develops and tests a structural model that incorporates a number of factors that are likely to influence the financial performance of SMEs in the economy.

2. Theoretical background

A common way to assess SME performance quantitatively is through their financial performance. Financial performance measures allow an organisation to assess whether its overall strategy and operations are effective in improving the bottom-line. These measures traditionally consist of evaluations of profitability, growth, shareholder value, and return on investment (Kaplan & Norton Citation1992). In some cases, both financial and marketing performance is treated as a singular unit of measure for performance (Weerawardena Citation2003). Albeit, they can and have also been treated as two distinct units of measure for total performance (Vorhies & Morgan Citation2005). Moreover, a third method also exists where both measures are treated as distinct constructs for performance (Hooley et al. Citation2005).

3. Determinants of SME performance

3.1. Management capability

Management capability of SMEs as a determinant of financial performance, is well documented in existing literature, with evidence highlighting its importance in the process and success of innovation within the organisation (Pfirrmann Citation1995; Soderquist et al. Citation1997; Cobbenhagen Citation2000). Existing research posits that management and innovation capability are closely linked, such that usually the former precedes the latter (Hooley et al. Citation2005). Furthermore, findings from empirical research lend further support to the idea that superior management capability will usually create conditions ideal to optimise innovation capability. A significant relationship between the two has been observed in various studies (Trott Citation1998; Tidd & Bessant Citation2013).

3.2. Innovation capability

Innovation can be defined as a process within an organisation to adopt change. The changes can be in terms of implementation of a new process, policy, or in the ways of doing things inside the organisation (Damanpour Citation1987; Garcia & Calantone Citation2002). Innovation capability adds value to an organisation by always being willing to adopt changes through the use of knowledge (Hsu et al. Citation2007; Hult et al. Citation2004). When studying performance, innovation cannot be ignored. Over the years, it has received significant attention and is perceived as extremely important for SMEs to develop a competitive edge, often through its contribution to marketing performance (Han et al. Citation1998; Hooley et al. Citation2005). Hence innovation is regarded as a key determinant of marketing performance. Moreover, innovation has been shown to have a significant role in enhancing the overall performance of an organisation (Weerawardena Citation2003; Hult et al. Citation2004; Weerawardena & O’Cass Citation2004; Weerawardena et al. Citation2006). The same has been observed in the Chinese context when comparing SME innovation and large enterprise innovation as well – Innovation has been observed to play a major role (Li & Mitchell Citation2009).

In existing literature, there have been various attempts to classify innovation. Generally, innovation has been classified into three categories: service/product innovation, product method innovation, and market innovation (Jenssen & Randøy Citation2006). Another approach was to split innovation capability into four distinct dimensions referred to as production innovation, process innovation, position innovation and paradigm innovation (Tidd & Bessant Citation2013). Due to the rapid changing nature of technology, technological innovations have also been subject to much attention by academics (Teece Citation1986; Damanpour Citation1987; Utterback Citation1994; Tuominen & Hyvönen Citation2004; Lau & Lo Citation2019).

3.3. Autonomy

Management scholars have long recognised that reliance on a centralised strategic planning is insufficient and may be detrimental to organisational performance (Andersen Citation2000). Managers’ ability to make independent decisions is beneficial for businesses operating in a dynamic environment. In an entrepreneurial context, ‘independent spirit and freedom of action’ is necessary to develop new ventures and for value creation (Lumpkin et al. Citation2009, 47). Autonomy provides managers the freedom and flexibility to develop and enact entrepreneurial initiatives. Autonomy can be defined as the extent to which managers feel that they have enough freedom and flexibility to act within a firm (Pratono et al. Citation2018). Under such conditions, entrepreneurial initiatives from individuals with the firm flourishes (Johansson et al. Citation2015). Past findings have identified autonomy as a key component in the creation of value within enterprises (Lumpkin et al. Citation2009). The presence of autonomy can bring benefits such as better team working, originality and encourage participation (Kakar Citation2018). Finally, autonomy has also been empirically found to have a significant contribution to the performance level of SMEs (Pratono et al. Citation2018). Andersen (Citation2000) also demonstrates a positive influence of autonomous actions on corporate performance.

3.4. Competencies

Competencies are the underlying characteristics such as generic and specific knowledge, motives, traits, self-images, social roles, and skills that influence the financial sustainability of SMEs (Li Citation2009). It is defined as an individual traits such as knowledge, skills and/or abilities need to perform a particular job (Baum et al. Citation2001) and includes strategic, conceptual, opportunity, organising, relationship, technical and personal attributes (Ahmad & Seet Citation2009; Ahmad et al. Citation2010). Strategic competency consists of thinking which reflects the ability of the leader to develop future vision and take action which necessitates them to think beyond day-to-day operations (Stonehouse & Pemberton Citation2002; Ahmad et al. Citation2010). Such a vision helps entrepreneurs to focus their actions and decisions more strategically which in turn provides firms advantages over their competitors. These strategies link firm resources and their ability to gain competitive advantage to overcome organisational uncertainty (Parnell et al. Citation2000). Operating in a dynamic environment often results in misfit between firm strategies and external demand which in turn force organisations to change their strategy and business structure when required. Consequently, the ability to make strategic change helps entrepreneurs to adapt and adjust the business operations to meet the current demand in the industry.

The ability to think analytically and to cope with uncertainty depends heavily on conceptual abilities (Bird & Beechler Citation1995). Conceptual competency reflects the conceptual capability of entrepreneurs such analysing, problem solving, decision-making, innovating and risk taking (Ahmad et al. Citation2010; Man et al. Citation2008). Conceptual competency includes the mental ability to coordinate all of the organisation’s interests and activities (Chandler & Jansen Citation1992). Being creative, innovative and flexible especially in handling opportunities, risks and uncertainties show the important capability which allow entrepreneurs to make a difference (Thompson Citation1999). Entrepreneurs, especially those operating in SMEs, face various situations where they need to make quick decisions, therefore having the abilities to carry out high level of conceptual activities are vital for the survival and success of their business (Ahmad et al. Citation2010). Opportunity competency relates to the ability of an entrepreneur to recognise and take advantage of opportunities. Recognising high quality opportunities triggers the creation of organisations and to embrace the various risks needed to turn the opportunities into profitable outcome. The readiness to seize relevant opportunities is a necessary competency for growing companies (Snell & Lau Citation1994; Choi & Shepherd Citation2004).

Relationship competency refers to an entrepreneur’s ability to maintain good relationships with other individuals and organisations so as to be able to have access to information and data (Ahmad et al. Citation2010). This in line with resource dependency theory, suggesting that entrepreneurs use their social relations to get the resources they need to launch a business (Barringer & Harrison Citation2000; Jenssen Citation2001). Networks are essential for small firms to obtain advice and support from lawyers, accountants and consultants (Duchesneau & Gartner Citation1990; Ramsden & Bennett Citation2005) as well as government bodies, research and training institutes and even suppliers and customers (Ritter & Gemünden Citation2004). Some studies validate a positive relationship between managers’ competency and performance (Russell Citation2001; Levenson et al. Citation2006). In another study, Junges et al. (Citation2015) find innovation competency to influence performance of firms in the information technology sector.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data collection and questionnaire design

Data were collected using a survey method based on a structured questionnaire. Before the questionnaire was designed, the researchers organised a workshop session with members of the SME community, representatives of Mauritius Tourism Authority, and other key stakeholders on 30 March 2018. The opinions of the participants were sought on the topic and following a review of the existing literature, the questionnaire was designed. Before data collection, the necessary ethical clearance was sought from the relevant authorities. The survey was administered to SMEs operating in the tourism sector of Mauritius between June and November 2018. In the majority of cases, a drop-off pick-up method was used to collect data. This method has the advantages of yielding a high response rate and reducing non-coverage error (Steele et al. Citation2001). Three hundred and ninety responses were obtained, out of which four were discarded due to several missing responses across the scale items, resulting in a valid sample of 386.

Seven-point Likert scales were used to measure the constructs of interest, namely: competence, autonomy, managerial capability, innovation capability and SME performance. The measurement scales were adapted from previously validated scales. Competence was measured using indicators adapted from the study of Omerzel & Antončič (Citation2008). It comprised of indicators measuring different skills such as teamwork, leadership, communication skills, accounting and time. Autonomy was measured using a set of items adapted from the study of Menon & Hartmann (Citation2002). The latter included items such as ‘I can influence decisions taken in my department’, ‘I can influence the way work is done in my department’, and ‘I have the authority to make decisions at work’. Scales to measure Managerial and Innovation Capability were adapted from the study of Hooley et al. (Citation2005) and Merrilees et al. (Citation2011). Items used to measure managerial capability included: ‘My business has better operational management expertise’, ‘My business has better overall management capabilities’, ‘My business is able to execute marketing strategies’, ‘My business manages its supply chain better’; Innovation capability was measured through statements such as: ‘Better at developing new ideas to help customers’, ‘More able to fast track new offerings to customers’, ‘More able to manage processes to keep costs down’ and ‘More able to package a total solution to solve customer problems.’ Finally, to measure SME performance, indicators were adapted from the study of Hooley et al. (Citation2005). The measures for SME performance consisted of statements such as ‘is more profitable’, ‘has a better return on investment’, ‘is able to reach financial goals’, ‘stronger growth in sales revenue’, ‘better able to acquire new customers’, ‘has a greater market share’ and ‘able to increase sales to existing customers.’

4.2. Data analysis procedure

The theoretical model of the study is tested using structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM allows researchers to study real-life phenomenon and ‘provides a useful forum for sense-making and in so doing link philosophy of science to theoretical and empirical research’ (Bagozzi & Yi Citation2012). SEM is a statistical procedure for testing measurement, functional, and predictive hypotheses that approximate world realities (Bagozzi & Yi Citation2012). Its ability lies in the assessment of latent (unobservable) variables at the observation level (measurement model) and testing hypothesised relationships between latent variables at the theoretical level (structural model) (Hair et al. Citation2012). SEM has become increasingly popular in social and behavioural sciences and is considered one of the most widely used statistical techniques for testing complex models that involve several dependent and independent variables (MacCallum & Austin Citation2000; Heene et al. Citation2012). The two approaches to SEM include co-variance based SEM and partial least square (PLS)-SEM. Given the present study’s focus on prediction of the outcome variable (SME performance), the PLS-SEM technique is of particular relevance (Richter et al. Citation2016; Rigdon Citation2016; Sarstedt et al. Citation2017). The PLS-SEM algorithm relies on the estimation of composites instead of covariances and this allows for the estimating coefficients having optimum effects on the model’s ability to predict the outcome variable (Rigdon et al. Citation2017). We use the SmartPLS3 software developed by Ringle et al. (Citation2015) to test the model.

5. Analysis and findings

5.1. Analysis of sample profile

A valid sample of 384 respondents was obtained, which is a satisfactory number of observations based on the G-Power analysis. The demographic profile of the survey respondents is presented in . A slight majority of 52.6% is female. With respect to the age profile, the sample was dominated by respondents between the age of 40 and 60 (44.7%). Around 38% of the sample are holders of an undergraduate degree and around 8% holds a post-graduate qualification. The majority does not have formal university education (52.6%). In terms of the legal status of the SMEs, the majority are sole proprietor owned (60.6%). The SMEs are fairly distributed across different sectors. The majority of them are tourism start-ups (56.7%).

Table 1. Sample profile of respondents and SMEs.

5.2. Structural equation model

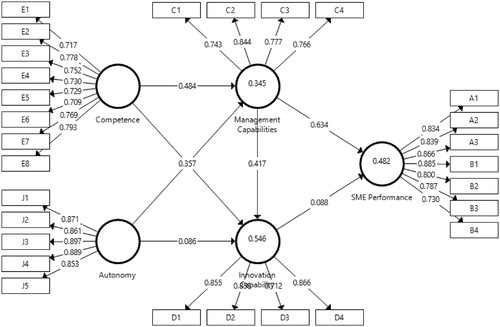

We followed a two-stage approach process to test the structural model. First, we assess the psychometric properties of the measurement model (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon Citation2012; Nunkoo et al. Citation2013). shows the results of the measurement model testing. As shown, performance, management capability and innovation capability that are assessed using a reflective measurement models, have satisfactory reliability and validity scores. In the case of reliability, all observed Cronbach’s alpha scores were above the 0.7 threshold value which demonstrate an adequate level of internal consistency. As for the validity all outer loadings were observed to be above the 0.7 value; the AVE scores as well were all observed to be at a satisfactory level above the established threshold value of 0.5. Furthermore, the bias-corrected confidence interval of the HTMT values can be observed not to contain 1, hence making it satisfactory to ascertain discriminant validity (Hair et al. Citation2017) ().

Table 2. Properties of the measurement model.

Following the validation of the measurement models, the next step is to test the structural model and evaluate the specific path relationships. It can be observed through the results that 48% (R2 = 0.48) of variation in performance can be explained through management and innovation capability. Additionally, the bootstrapping procedure set at 5000 iteration, at a 95% confidence level resulted in confidence interval ranging in values not including zero implying statistical significance. As presented in above, managerial capability has a significant positive direct effect on SME performance (β = 0.634; BCa = [0.523–0.737]) while innovation capability does not (β = 0.088; BCa = [−0.030–0.194]). Managerial capability is found to be significantly predicted by both autonomy (β = 0.086; BCa = [0.001–0.171]) and competence (β = 0.484; BCa = [0.402–0.572]). Moreover, the results show that the competence of SME owners has a much stronger effect on overall managerial capability as compared to autonomy. The results also show that innovation capability does not exert a significant effect on SME performance (β = 0.088; BCa = [−0.030–0.194]).

Table 3. Results of Structural Model (Assessment of Direct and Total Effects).

6. Discussion

Results indicate that managers’ autonomy is a significant determinant of SME performance, suggesting that more autonomous managers lead to improved SME performance. This is because autonomy facilitates entrepreneurial actions by facilitating the exploration of business opportunities, development of new business concepts, and their execution through to completion (Lumpkin et al. Citation2009). Our study confirms previous research, suggesting that managers who feel they have enough flexibility to take managerial decisions report better firm’s performance (Johansson et al. Citation2015). In the context of this study, autonomy refers to manager’s freedom to act and the latitude they have when formulating strategic decision in their organisation and the development of the SEM strategy (Montanari Citation1978). The benefits of the execution of managerial discretion for greater performance consequences have been well discussed in the existing literature (Magnan & Stonge Citation1997; Keegan & Kabanoff, Citation2008; Li & Tang Citation2010; Sirén et al. Citation2018).

Our results also indicate competence to be a significant determinant of performance. Higher level of managerial competence was positively related to performance. In SMEs, managerial human capital plays an important role in determining the performance of the organisation. Managers’ knowledge helps to develop the required capabilities that are essential and decisive in strategic outcomes. In addition, managers are the main factor behind the initiation, development, sustenance, and success of a firm’s (Freeman et al. Citation2006). The main approaches in the social science literature to identify competence build from the scientific principles of rationalistic research tradition that focus on job analysis (Cascio Citation1995). Furthermore, the study also demonstrates that skills of the managers were positively related to managerial competency. The literature identifies skill as an important determinant of competence and indirectly, performance (Yamazaki Citation2010). Empirical studies have attempted to establish relationships between skills, competence and performance, with the conclusion that performance and competence has to be accompanied by difference types of managerial skills (Black & Mendenhall Citation1990; Yamazaki & Kayes Citation2004; Seak & Enderwick Citation2008).

We also demonstrate empirically that skills are positively related to innovation capabilities of the managers, suggesting that more skillful managers demonstrate more capabilities to bring innovation to their SMEs. The role of skill in innovation has been validated across several studies carried out in different context (Thoenig & Verdier Citation2003; Compagni et al. Citation2015). From an economic perspective, skills are considered as an engine for growth and productivity of firms (Nelson & Phelps Citation1966). Evidence from both theory and empirical analyses suggest that skills drive the capacity of manager to innovate, which consequently influences productivity, growth, and market value of firms.

However, empirical analysis is mainly concentrated with large firms, although from a theoretical perspective, we can extrapolate such evidences to SMEs. The OECD’s Innovation strategy report highlights that in some OECD countries firms now invest as much in the intangible assets such as skill improvement to improve the innovation capabilities of managers (The OECD Innovation Strategy, Citation2010). Our study has also established a significant positive relationship between management capability and innovation capability. This finding is not surprising given the ample evidence that validate a similar relationship in the existing literature. Several firms have improved the management capability in an attempt to improve innovation capability. For example, FedEx adopts an outside-in approach to create innovative products (Battor et al. Citation2008).

7. Managerial implications

The study provides important managerial implications for improving the performance of SMEs. For better performance, it is imperative for SMEs to improve their management capability. Our results indicate that SMEs with more autonomous managers’ report improved performance. Thus, it is important that managers of SME are empowered to make strategic decision. The concept of empowerment is originally derived from participative management theories and suggests that manager’s involvement in decision-making leads to several benefits for the organisation. Thus, the organisational structure of SMEs should encourage managers to participate fully in the decision-making processes. SMEs should be a light organisational structure that reduces bureaucratic decision-making processes involving several layers of management. As Martin & Bush (Citation2006) argue,

… a participative climate that emphasizes individual contribution and employee initiative accepts and fosters the notion that employee creativity and self-determination are critical success factors in a competitive environment. In turn, as work climate perceptions become increasingly positive, employees likely perceive greater meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact in their work. (p. 420)

Improving innovation capabilities remains an important consideration for SME to improve their performance. SME should recognise that innovation provides them with a competitive advantage and help them play a dominate role in the industry. SME therefore has to focus on such processes that lead to more efficient production at the lowest possible costs. Furthermore, SME can use process and system innovation to improve productivity. They can, for example, implement lean principles that aim to eliminate ‘waste’ from production to customer relations, product design, supplier networks and factory management with objective being less human effort, inventory and time to develop products, within minimum space to become highly responsive to customer demand and produce quality products economically.

Developing managerial skills is another path to improve management and innovation capabilities as our findings suggests. The government should recognise the importance of managerial skills for the sustainability of SMEs in Mauritius and should provide incentives or directly support skills development programme for SME managers. Such programmes should at improving skills of SME managers such as those related to people management, business finance, communication, negotiations, project management, business strategy and planning, leadership, and other fundamental management skills.

Despite the value of this study for theory and practice, it is not without limitations. First, the study relied on data collected using self-reported measures. Therefore, common-method bias could have influenced the results, although we took various measures to limit such biases in the study. Second, the theoretical model contains only a limited number of determinants of financial performance. The literature evidences a number of other determinants such as those related to the macro-economic conditions of a country. It is therefore recommended that future research takes into account additional factors that can enhance the predictive power of the model. Third, the study is based on a survey design which is a non-experimental research approach. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted in the light of the caveats inherent to survey research, commonly referred to as the total survey error (Eckman & de Leeuw Citation2017; Nunkoo et al. Citation2018). The latter is defined as ‘the accumulation of all errors that may arise in the design, collection, processing, and analysis of survey data. In this context, a survey error is defined as the deviation of a survey response from its underlying true value’ (Biemer Citation2010, 817). Survey errors can pose challenges to the reliability and validity of research findings. Finally, the specific socio-economic and political conditions of Mauritius limit the extent to which the findings can be generalised to other economies.

8. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to assess the determinants of SME performance in Mauritius. To this end, a theoretical model was developed based on a review of the existing literature in the field. The model proposes that management capability, autonomy, competence, self-confidence, and skills are the antecedents of SME performance. The model was tested using a structural equation modelling approach on data collected from 384 SME owners/managers. The results indicate managerial capability has a strong influence on SEM performance, while the former is influenced positively by mangers’ autonomy. Given the socio-economic importance of SMEs to the Mauritian economy, the results provide crucial information to government and policy-makers that can used to develop macro-economic policies that increase their contribution to the socio-economic development of the country. For entrepreneurs, the study provides insights on areas of interventions that can lead to an improvement in the financial performance of their organisations. Despite the study limitations, it contributes to a theoretical understanding of the determinants of financial performance in African economies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, NH, Halim, HA & Zainal, SRM, 2010. Is entrepreneurial competency the silver bullet for SME success in a developing nation. International Business Management 4(2), 67–75.

- Ahmad, NH & Seet, PS, 2009. Dissecting behaviours associated with business failure: A qualitative study of SME owners in Malaysia and Australia. Asian Social Science 5(9), 98–104.

- Andersen, TJ, 2000. Strategic planning, autonomous actions and corporate performance. Long Range Planning 33(2), 184–200.

- Bagozzi, RP & Yi, Y, 2012. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40(1), 8–34.

- Barringer, BR & Harrison, JS, 2000. Walking a tightrope: Creating value through interorganizational relationships. Journal of Management 26(3), 367–403.

- Battor, M, Zairi, M & Francis, A, 2008. Knowledge-based capabilities and their impact on performance: A best practice management evaluation. Business Strategy Series 9(2), 47–56.

- Baum, JR, Locke, EA & Smith, KG, 2001. A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal 44(2), 292–303.

- Biemer, PP, 2010. Total survey error: Design, implementation, and evaluation. Public Opinion Quarterly 74(5), 817–48.

- Bird, A & Beechler, S, 1995. Links between business strategy and human resource management strategy in US-based Japanese subsidiaries: An empirical investigation. Journal of International Business Studies 26(1), 23–46.

- Black, JS & Mendenhall, M, 1990. Cross-cultural training effectiveness: A review and a theoretical framework for future research. Academy of Management Review 15(1), 113–36.

- Cascio, WF, 1995. Whither industrial and organizational psychology in a changing world of work? American Psychologist 50(11), 928–39.

- Chandler, G & Jansen, E, 1992. The founder’s self-assessed competence and venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing 7(3), 223–36.

- Choi, Y & Shepherd, D, 2004. Entrepreneurs’ decisions to exploit opportunities. Journal of Management 30(3), 377–95.

- Cobbenhagen, J, 2000. Successful innovation. 1st ed. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

- Compagni, A, Mele, V & Ravasi, D, 2015. How early implementations influence later adoptions of innovation: Social positioning and skill reproduction in the diffusion of robotic surgery. Academy of Management Journal 58(1), 242–78.

- Damanpour, F, 1987. The adoption of technological, administrative, and ancillary innovations: Impact of organizational factors. Journal of Management 13(4), 675–88.

- Duchesneau, D & Gartner, W, 1990. A profile of new venture success and failure in an emerging industry. Journal of Business Venturing 5(5), 297–312.

- Eckman, S & de Leeuw, E, 2017. Editorial – special issue on total survey error (TSE). Journal of Official Statistics 33(2), 301.

- Freeman, S, Edwards, R & Schroder, B, 2006. How smaller born-global firms use networks and alliances to overcome constraints to rapid internationalization. Journal of International Marketing 14(3), 33–63.

- Garcia, R & Calantone, R, 2002. A critical look at technological innovation typology and innovativeness terminology: A literature review. Journal of Product Innovation Management 19(2), 110–32.

- Hair, JF, Sarstedt, M, Pieper, TM & Ringle, CM, 2012. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: a review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long range planning, 45(5-6), 320–340.

- Hair, J, Sarstedt, M, Ringle, C & Gudergan, S, 2017. Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. 1st ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Han, J, Kim, N & Srivastava, R, 1998. Market orientation and organizational performance: Is innovation a missing link? Journal of Marketing 62(4), 30–45.

- Heene, M, Hilbert, S, Freudenthaler, H & Bühner, M, 2012. Sensitivity of SEM fit indexes with respect to violations of uncorrelated errors. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 19(1), 36–50.

- Hooley, G, Greenley, G, Cadogan, J & Fahy, J, 2005. The performance impact of marketing resources. Journal of Business Research 58(1), 18–27.

- Hsu, RC, Lawson, D & Liang, TP, 2007. Factors affecting knowledge management adoption of Taiwan small and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development 4(1), 30–51.

- Huarng, K & Hui-Kuang Yu, T, 2011. Entrepreneurship, process innovation and value creation by a non-profit SME. Management Decision 49(2), 284–96. doi: 10.1108/00251741111109160

- Hult, G, Hurley, R & Knight, G, 2004. Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Industrial Marketing Management 33(5), 429–38.

- Jenssen, J, 2001. Social networks, resources and entrepreneurship. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 2(2), 103–9.

- Jenssen, J & Randøy, T, 2006. The performance effect of innovation in shipping companies. Maritime Policy and Management 33(4), 327–43.

- Johansson, M, Keränen, J, Hinterhuber, A, Liozu, S & Andersson, L, 2015. Value assessment and pricing capabilities—how to profit from value. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management 14(3), 178–97.

- Junges, FM, Gonçalo, CR, Garrido, IL & Fiates, GGS, 2015. Knowledge management, innovation competency and organisational performance: A study of knowledge-intensive organisations in the IT industry. International Journal of Innovation and Learning 18(2), 198–221.

- Kakar, A, 2018. Engendering cohesive software development teams: Should we focus on interdependence or autonomy? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 111, 1–11.

- Kaplan, R & Norton, D, 1992. The balanced scorecard. Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA, pp. 71–9.

- Keegan, J & Kabanoff, B, 2008. Indirect industry-and subindustry-level managerial discretion measurement. Organizational Research Methods 11(4), 682–94.

- Kirsten, M & Rogerson, CM, 2002. Tourism, business linkages and small enterprise development in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 19(1), 29–59.

- Kober, R, Subraamanniam, T & Watson, J, 2012. The impact of total quality management adoption on small and medium enterprises’ financial performance. Accounting and Finance 52(2), 421–38.

- Lau, A & Lo, W, 2019. Absorptive capacity, technological innovation capability and innovation performance: An empirical study in Hong Kong. International Journal of Technology Management 80(1/2), 107–148.

- Levenson, AR, Van der Stede, WA & Cohen, SG, 2006. Measuring the relationship between managerial competencies and performance. Journal of Management 32(3), 360–80.

- Li, X, 2009. Entrepreneurial competencies as an entrepreneurial distinctive: An examination of the competency approach in defining entrepreneurs. MSc, Singapore Management University.

- Li, X & Mitchell, R, 2009. The pace and stability of small enterprise innovation in highly dynamic economies: A China-based template. Journal of Small Business Management 47(3), 370–97.

- Li, J & Tang, YI, 2010. CEO hubris and firm risk taking in China: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Academy of Management Journal 53(1), 45–68.

- Lumpkin, G, Cogliser, C & Schneider, D, 2009. Understanding and measuring autonomy: An entrepreneurial orientation perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33(1), 47–69.

- MacCallum, R & Austin, J, 2000. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology 51(1), 201–26.

- Magnan, ML & Stonge, S, 1997. Bank performance and executive compensation: A managerial discretion perspective. Strategic Management Journal 18(7), 573–81.

- Man, T, Lau, T & Snape, E, 2008. Entrepreneurial competencies and the performance of small and medium enterprises: An investigation through a framework of competitiveness. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 21(3), 257–76.

- Martin, C & Bush, A, 2006. Psychological climate, empowerment, leadership style, and customer-oriented selling: An analysis of the sales manager-salesperson dyad. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34(3), 419–38.

- Masurel, E & Nijkamp, P, 2004. Differences between first-generation and second-generation ethnic start-ups: Implications for a new support policy. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 22(5), 721–37.

- Menon, S & Hartmann, L, 2002. Generalizability of Menon’s empowerment scale. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 2(2), 137–53.

- Merrilees, B, Rundle-Thiele, S & Lye, A, 2011. Marketing capabilities: Antecedents and implications for B2B SME performance. Industrial Marketing Management 40(3), 368–75.

- Ministry of Business, Enterprise and Cooperatives. 2017. 10-year master plan for the SME sector in Mauritius: Accelerating innovation and growth. http://enterbusiness.govmu.org/English/Documents/SME%20Master%20Plan_Full%20Version_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2020.

- Montanari, J, 1978. Managerial discretion: An expanded model of organization choice. Academy of Management Review 3(2), 231–41.

- Nelson, R & Phelps, E, 1966. Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. The American Economic Review 56(1/2), 69–75.

- Nunkoo, R & Ramkissoon, H, 2012. Structural equation modelling and regression analysis in tourism research. Current Issues in Tourism 15(8), 777–802.

- Nunkoo, R, Ramkissoon, H & Gursoy, D, 2013. Use of structural equation modeling in tourism research. Journal of Travel Research 52(6), 759–71.

- Nunkoo, R, Ribeiro, MA, Sunnassee, V & Gursoy, D, 2018. Public trust in mega event planning institutions: The role of knowledge, transparency and corruption. Tourism Management 66, 155–66.

- OECD. 2010. The OECD innovation strategy: Getting a head start on tomorrow. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Ogunyomi, P & Bruning, N, 2016. Human resource management and organizational performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Nigeria. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27(6), 612–34.

- Omerzel, DG & Antončič, B, 2008. Critical entrepreneur knowledge dimensions for the SME performance. Industrial Management and Data Systems 108(9), 1182–99.

- Onkelinx, J, Manolova, T & Edelman, L, 2016. The human factor: Investments in employee human capital, productivity, and SME internationalization. Journal of International Management 22(4), 351–64.

- Parnell, JA, Carraher, S & Odom, R, 2000. Strategy and performance in the entrepreneurial computer software industry. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship 12(3), 49–66.

- Peberdy, S & Rogerson, C, 2000. Transnationalism and non-South African entrepreneurs in South Africa’s small, medium and micro-enterprise (SMME) economy. Canadian Journal of African Studies/La Revue canadienne des études africaines 34(1), 20–40.

- Pfirrmann, O, 1995. Path analysis and regional development: Factors affecting R and D in West German small and medium sized firms. Regional Studies 29(7), 605–18.

- Pillay, M & Rogerson, CM, 2013. Agriculture-tourism linkages and pro-poor impacts: The accommodation sector of urban coastal KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Applied Geography 36, 49–58.

- Pratono, A, Ratih, R & Arshad, D, 2018. Does entrepreneurial autonomy foster SME growth under technological turbulence? The empirical evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science 3(3), 170–8.

- Ramsden, M & Bennett, R, 2005. The benefits of external support to SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 12(2), 227–43.

- Richter, N, Cepeda, G, Roldán, J & Ringle, C, 2016. European management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Management Journal 34(6), 589–97.

- Rigdon, E, 2016. Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: A realist perspective. European Management Journal 34(6), 598–605.

- Rigdon, E, Sarstedt, M & Ringle, C, 2017. On comparing results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five perspectives and five recommendations. Marketing ZFP 39(3), 4–16.

- Ringle, CM, Wende, S & Becker, J-M, 2015. SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. http://www.smartpls.com.

- Ritter, T & Gemünden, H, 2004. The impact of a company’s business strategy on its technological competence, network competence and innovation success. Journal of Business Research 57(5), 548–56.

- Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2011. Tourism research within the Southern African development community: Production and consumption in academic journals, 2000–2010. Tourism Review International 15(1-2), 213–24.

- Rogerson, CM, 2000. Successful SMEs in South Africa: The case of clothing producers in the Witwatersrand. Development Southern Africa 17(5), 687–716.

- Rogerson, CM, 2004a. The impact of the South African government’s SMME programmes: A ten-year review (1994–2003). Development Southern Africa 21(5), 765–84.

- Rogerson, CM, 2004b. Urban tourism and small tourism enterprise development in Johannesburg: The case of township tourism. GeoJournal 60(3), 249–57.

- Rogerson, CM, 2005. Unpacking tourism SMMEs in South Africa: Structure, support needs and policy response. Development Southern Africa 22(5), 623–42.

- Rogerson, CM, 2006. Creative industries and urban tourism: South African perspectives. Urban Forum 17(2), 149–66.

- Rogerson, CM, 2007. Tourism routes as vehicles for local economic development in South Africa: The example of the Magaliesberg Meander. Urban Forum 18(2), 49–68.

- Rogerson, CM, 2008. Tracking SMME development in South Africa: Issues of finance, training and the regulatory environment. Urban Forum 19(1), 61–81.

- Rogerson, CM, 2010. Local economic development in South Africa: Strategic challenges. Development Southern Africa 27(4), 481–95.

- Rogerson, CM, 2012. Tourism–agriculture linkages in rural South Africa: Evidence from the accommodation sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 477–95.

- Russell, CJ, 2001. A longitudinal study of top-level executive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(4), 560–73.

- Sarstedt, M, Ringle, CM & Hair, JF, 2017. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Homburg C, Klarmann M, & Vomberg A, Handbook of market research, 1st ed., Springer, Heidelberg.

- Saunila, M, Ukko, J & Rantanen, H, 2014. Does innovation capability really matter for the profitability of SMEs? Knowledge and Process Management 21(2), 134–42.

- Seak, N & Enderwick, P, 2008. The management of New Zealand expatriates in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 19(7), 1298–313.

- Sirén, C, Patel, PC, Örtqvist, D & Wincent, J, 2018. CEO burnout, managerial discretion, and firm performance: The role of CEO locus of control, structural power, and organizational factors. Long Range Planning 51(6), 953–71.

- Snell, R & Lau, A, 1994. Exploring local competences salient for expanding small businesses. Journal of Management Development 13(4), 4–15.

- Soderquist, K, Chanaron, J & Motwani, J, 1997. Managing innovation in French small and medium-sized enterprises: An empirical study. Benchmarking for Quality Management and Technology 4(4), 259–72.

- Steele, J, Bourke, L, Luloff, AE, Liao, PS, Theodori, GL & Krannich, RS, 2001. The drop-off/pick-up method for household survey research. Community Development 32(2), 238–50.

- Stonehouse, G & Pemberton, J, 2002. Strategic planning in SMEs – some empirical findings. Management Decision 40(9), 853–61.

- Teece, D, 1986. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy 15(6), 285–305.

- Thoenig, M & Verdier, T, 2003. A theory of defensive skill-biased innovation and globalization. American Economic Review 93(3), 709–28.

- Thompson, J, 1999. The world of the entrepreneur – a new perspective. Journal of Workplace Learning 11(6), 209–24.

- Tidd, J & Bessant, J, 2013. Managing innovation. 5th ed. Wiley, London.

- Todaro, M & Smith, S, 2012. Economic development. Pearson Education, Boston, MA.

- Trott, P, 1998. Growing businesses by generating genuine business opportunities: A review of recent thinking. Journal of Applied Management Studies 7(2), 211–22.

- Tuominen, M & Hyvönen, S, 2004. Organizational innovation capability: A driver for competitive superiority in marketing channels. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 14(3), 277–93.

- Utterback, J, 1994. Mastering the dynamics of innovation. 1st ed. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

- Visser, G & Rogerson, CM, 2004. Researching the South African tourism and development nexus. GeoJournal 60(3), 201–15.

- Vorhies, D & Morgan, N, 2005. Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing 69(1), 80–94.

- Weerawardena, J, 2003. The role of marketing capability in innovation-based competitive strategy. Journal of Strategic Marketing 11(1), 15–35.

- Weerawardena, J & O’Cass, A, 2004. Exploring the characteristics of the market-driven firms and antecedents to sustained competitive advantage. Industrial Marketing Management 33(5), 419–28.

- Weerawardena, J, O’Cass, A & Julian, C, 2006. Does industry matter? Examining the role of industry structure and organizational learning in innovation and brand performance. Journal of Business Research 59(1), 37–45.

- Yamazaki, Y & Kayes, D, 2004. An experiential approach to cross-cultural learning: A review and integration of competencies for successful expatriate adaptation. Academy of Management Learning and Education 3(4), 362–79.

- Yamazaki, Y, 2010. Impact of learning styles on learning-skill development in higher education. Working Papers EMS_2010_09, Research Institute, International University of Japan.