ABSTRACT

Central parts of southern Africa are expected to face major environmental and economic changes in the near future, calling for proactive thinking on how local people could diversify their livelihoods. In Botswana, the tourism industry is considered as a major option for economic diversification and current tourism policies include a strong emphasis on tourism that participates in and benefits communities. The developmental impact of tourism depends on how the local communities perceive their livelihood options and the role of tourism. This paper analyses how community members in selected villages in Kalahari Desert perceive the current and estimated future impacts of climate change and how these impacts may influence their livelihoods in future and what role the tourism industry may play in that process. Based on the results, there are minimal local benefits and participation in tourism, which limits the potential of tourism to work for sustainable local development in practice.

1. Introduction

In southern Africa, especially the central parts are predicted to undergo considerable environmental changes in the near future. Global climate change is creating challenges for the region, and especially for rural and remote communities who need to prepare and adapt to ongoing environmental changes. Specifically, southern African dry, hot and water-stressed regions such as Kgalagadi District (a part of the Kalahari desert) in southwest Botswana are facing greater challenges and effects than the global average of global climate change: global warming of 1.5°C would lead to an average temperature rise (above the pre-industrial time) in Botswana of 2.2°C (ASSAR, Citation2015; Mberego, Citation2017). Water availability (and quality) is perhaps the primary element through which the impacts of climate change are being felt in the region (see Mpandeli et al., Citation2018), whose economy has been recently based on arable and pastoral farming. Due to climate change impacts, such as extreme droughts and heat waves, these economies are becoming increasingly vulnerable and economically unviable in the region (see Totolo & Chanda, Citation2003; Atlhopheng et al., Citation2019). These economies, however, still provide the main sources of living for a majority of the population (Moswete & Thapa, Citation2018).

It has become highly evident that socio-ecological challenges created by global climate change call for adaptation in local communities and promote (or encourage) proactive thinking on how people could and should develop their livelihoods in future (see Lew, Citation2014; Mberego, Citation2017; Tervo-Kankare et al., Citation2018). In order to be less vulnerable and, thus, resilient, local communities may need to change or diversify their livelihoods (see England et al., Citation2018; Hoogendoorn & Fitchett, Citation2018). This development of adaptive strategies and economic diversification is highly important with respect to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, Citation2015), which define the agenda for global development to 2030 by addressing challenges related to poverty, climate and environmental degradation (Atlhopheng & Segaetsho, Citation2019).

In general, economic diversification can be one tool for adaptation and sustainable local development. In Botswana, the promotion of the tourism industry is currently used for economic diversification (see UNWTO, Citation2008), specifically to lessen the high dependency on the mining sector (Mbaiwa, Citation2015). As a result, an increasing number of communities are reaching out for new economic opportunities potentially provided by this emerging opportunity called tourism development (Moswete & Thapa, Citation2018). Many major international agencies, such as the UNWTO and the World Bank, consider (sustainable) tourism as a tool for achieving the SDGs and ‘benefitting communities in destinations around the world’ (World Bank Group, Citation2017:5), especially in the Global south.

In Botswana, tourism development and opportunities have been skewed to the northern parts of the country with a strong focus on wildlife and wilderness tourism (Mbaiwa, Citation2005, Citation2017) and the tourism potential of the Kgalagadi region has not been given enough attention (Saarinen et al., Citation2012). However, the area and its wilderness characteristics, communities and cultural diversity offer opportunities for tourism development (see Phuthego & Chanda, Citation2004; Moswete et al., Citation2009; Hambira, Citation2017). Current tourism development plans support the diversification policy spatially and thematically (see Moswete & Thapa, Citation2015). First, tourism offerings need to be developed in different parts of the country, including the Kgalagadi region. Secondly, instead of wilderness resources alone, tourism products and activities should include participation of local communities and cultures (Rylance & Spenceley, Citation2017; Moswete & Thapa, Citation2018). The key goals aiming to achieve the diversification vision centralising the local involvement and benefits are e.g.: to substantially increase the share of local ownership and management in the industry; to promote labour-intensive tourism practices; to develop and improve tourism skills and provide tourism education and training; to encourage community participation; and to create awareness of tourism among the population (UNWTO, Citation2008; see Saarinen et al., Citation2014; Monare et al., Citation2016; Mbaiwa, Citation2017).

This need to initiate economic diversification and local benefits based on tourism, together with estimated impacts of environmental change, have created high government level expectations on the prospective economic and employment role of the tourism industry in the different parts of the country (see Lenao & Saarinen, Citation2015), including the Kgalagadi region (Phuthego & Chanda, Citation2004; Moswete et al., Citation2012). There is also a strong emphasis on developing cultural tourism in Botswana as that form of tourism is seen as involving local people to tourism operations and products (Mbaiwa & Sakuze, Citation2009; Saarinen et al., Citation2014). In addition to the national policies and markets, however, the developmental impact of tourism depends greatly on how the local communities perceive their livelihood options and the role of tourism in their life and locality (see Saarinen, Citation2010; Adger et al., Citation2012; Moswete et al., Citation2012). Based on this it is crucial to understand how communities see their own prospects to participate in tourism development.

Therefore, this paper analyses how local community members perceive the current and estimated future impacts of environmental change and how these impacts may influence their livelihoods in future and what role the tourism industry may play in that process. Thus, in addition to the environmental change perceptions, a special focus is given on local perceptions concerning the impacts of tourism development and local benefits from and participation in tourism. The case study communities of Kang and Macheng (or Matšheng) villages are located in the northern part of the Kgalagadi District. These villages are situated along the key routes to one of the main attractions in south-western Botswana – the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (KTP). The KTP is made up of South Africa’s Kalahari Gemsbok National Park and Botswana’s Gemsbok National Park. The village of Kang is situated on the Trans-Kalahari Highway while Macheng villages are further away from the main highway (Moswete et al., Citation2009), which allows to evaluate if proximity in relation to expected tourist activities and flows plays a role in local perceptions of tourism’s benefits and future potential. First, the paper shortly describes climate change impacts on livelihoods in southern Africa at a general level and then focuses on the key issues in local participation in tourism. After that, the case study area and research methods are described, followed by the analysis and conclusions.

2. Climate change and livelihood issues in southern Africa

Climate change poses serious problems for sustainability, as climate change is often linked to changing and deepening inequities (Hoogendoorn & Fitchett, Citation2018; Masalila, Citation2019). In this respect, marginal or subsistent livelihoods are the most vulnerable in poor countries and rural areas (Pelling, Citation2011). As stated by Ashley & Maxwell (Citation2001:395): ‘Poverty is not only widespread in rural areas, but most poverty is rural’. Thus, the people and individuals with limited alternative livelihoods in rural areas will be the most affected as climate change poses risks to places, systems and communities and their access to natural resources (Paavola & Adger Citation2006). Indeed, previous studies from different peripheral, rural and indigenous communities (see Gentle & Maraseni, Citation2012; Willox et al., Citation2012) indicate that climate change creates major livelihood challenges to communities, and communities’ vulnerability relates to the environmental (and social) processes that limit the ability of systems to cope with climate change-related impacts (Adger et al., Citation2006).

While the effects of global climate change to southern African countries are expected to be serious, there are still major research and information gaps (Saarinen et al., 2012; Hambira & Saarinen, Citation2015; Hoogendoorn & Fitchett, Citation2018; Moswete et al., Citation2017). Local communities living in extreme environments will be highly impacted but in the case of Botswana and the wider Kalahari Desert, representing a large (900,000 square kilometres) semi-arid environment covering much of Botswana and parts of Namibia and South Africa, the local views and perceptions concerning environmental change have not been widely studied. These local views, however, may have a major effect on how people and communities can and/or will respond to climate change, as adaptation strategies are often driven by individuals’ (socially constructed) personal beliefs and perceptions of change (and obviously their chances to adapt) (Grothmann & Patt, Citation2012).

While climate change and its socio-economic contexts and impacts on development and sustainability are widely acknowledged, they are empirically less studied in the southern Africa region, especially in Botswana. Some studies on impacts of climate on communities highlight challenges for the poor (Gentle & Maraseni, Citation2012), stating that poor people are not often able to adapt, but rather ‘passively’ cope with the impacts. Contrast to passive coping, adaptation refers to a process through which communities are actively ‘able to reflect upon and enact change in those practices and underlying institutions that generate root and proximate causes of risk, from capacity to cope and further rounds of adaptation’ (Pelling, Citation2011:21). In the context of both coping and adaptation with the direct climate change impacts, poor households often face other related challenges such as limited access to markets services, knowledge, productive assets and government services, hence frustrating any livelihood diversification opportunities (Paavola & Adger Citation2006), including tourism.

3. Tourism for local development: Community participation, control and awareness

The tourism industry is often seen as a beneficial socio-economic instrument for local community development (Tosun, Citation1999; Moswete & Thapa, Citation2015), serving as a response to negative economic changes taking place in rural and peripheral areas (see Telfer & Sharpley, Citation2008). The World Bank Group (Citation2017), for example, outlined their list of 20 reasons why tourism works for development, specifically for sustainable development. The World Bank Group highlighted that tourism development can serve sustainable economic growth; social inclusiveness, employment, and poverty reduction; resource efficiency, environmental protection, and climate; cultural values, diversity, and heritage; and mutual understanding, peace, and security (see UNWTO, Citation2017). Although having a global sustainability view, these elements and the specific reasons for supporting the tourism industry in development are clearly based on the industry’s role as a local solution for global challenges in various places and communities (Saarinen, Citation2019). Therefore, local communities and their role in tourism can be regarded as the key issue when evaluating the sustainability of tourism development.

There has been considerable scholarship on tourism and its’ community relations. Research has been focusing on local perceptions and attitudes towards tourism, tourism development and impacts, sustainability of tourism and the local benefits of tourism in various community contexts (see Gursoy et al., Citation2009; Kim et al., Citation2013; Hunt et al., Citation2015). Past studies have identified different attitudinal responses and their reasons (Tosun, Citation1999, Citation2000; Saarinen, Citation2010) and a broad range of effects for communities (Pearce et al., Citation1996; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012). Based on the previous studies some of the key elements in tourism benefit creation are based on community participation, control and tourism awareness and knowledge, which are often intertwined in practice in complex ways in tourism planning and development processes (Saarinen, Citation2019). Obviously, communities are not homogenous units, thus, different community members and sub-groups may cope and react very differently with tourism development activities and their various impacts (see Nunkoo & Ramkissoo, Citation2011; Nunkoo & Smith, Citation2013). Communities may also have different ways of using local natural and/or cultural resources, which can influence their attitudes towards tourism development and specific operations. If the use of resources by the tourism industry conflicts with traditional local livelihoods, for example, the resistance and conflicting views towards tourism development are more likely to take place compared to symbiotic situations in resource utilisation (see Saarinen, Citation2019).

In order to minimise local conflicts and optimise local benefits, community participation is seen as the key element for locally beneficial and sustainable tourism planning and development (Scheyvens Citation2002; Li, Citation2006). Although participation represents the core issue, it is often vaguely used and conceptualised in tourism-community studies (Timothy, Citation1999; Scheyvens, Citation2002; Tosun, Citation2006). According to Tosun (Citation2000:615) participation ‘refers to a form of voluntary action in which individuals confront opportunities and responsibilities of citizenship’. In tourism, Pearce et al. (Citation1996:181) have outlined the term as ‘the involvement of individuals within a tourism-oriented community in the decision-making and implementation process with regard to major manifestations of political and socio-economic activities’. What this basically means is that in order to benefit from tourism, community members need to be involved in the industry and its operations (Kavita & Saarinen, Citation2016).

There are different models of community involvement (Thondhlana et al., Citation2015). Many of them are explicitly or implicitly based on Sherry Arnstein’s (Citation1969) seminal work on the ladder of participation, in which she categorises eight types of participation as Citizen Control, Delegated Power, Partnership (representing Citizen Power); Placation, Consultation, Informing (representing Tokenism); and Therapy and Manipulation (representing Non-participation). Tosun (Citation2006) has applied these to tourism-community relations by classifying the local involvement into coercive, induced, and spontaneous community participation. Tosun’s coercive participation is a formal top-down approach. In tourism it can take place in the implementation phase of certain tourism planning processes and development projects. However, it does not necessarily lead to a significant benefit sharing but can primarily benefit and serve the industry and its development needs. Induced participation involves a consultation, in which community members can share their views and opinions towards the implementation of the tourism development but they do not necessarily set the goals for tourism-based development (Tosun, Citation2000). Therefore, community members are symbolically heard and, thus, their role can be characterised by being passive recipients (i.e. objects) of tourism development and tourism-based benefits (Saarinen, Citation2011, Citation2012). Spontaneous participation represents a contrasting approach to the previous one by being based on an active role of community members. It emphasises a bottom-up approach and deeper participation in actual decision-making, which should also include a priority and goal setting for the industry and its resource and land uses (Tosun, Citation2006). In spontaneous participation community members are seen as active agents and subjects in tourism planning and development.

While direct participation is highly crucial, it is obvious that truly beneficial participation process for communities needs to go beyond a simple involvement with tourism alone. Indeed, based on the research literature, participating communities and their members need to have mechanisms to influence the decision-making processes in tourism planning and development (Hunt & Stronza Citation2014). This is implicitly included to Tosun’s (Citation2006) spontaneous participation idea. Based on this, people should have a control over tourism industry and its planning and development activities taking place in communities and using and impacting local resources (Hall, Citation2008). Simply, the question is about power relations between the tourism industry and local communities (Saarinen, Citation2019). Power issues and power-sharing are noted to be highly problematic issues between global private sector industry and local people (Church & Coles, Citation2007). The idea of power-sharing is built into the community participation also in Arnstein’s (Citation1969: 216) ladders: she has defined participation as ‘the redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens’ to have a say and share ‘the benefits’ of development. Related to this, many community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) models, which are widely utilised in southern Africa, are ideally based on the devolution of power from central government and tourism coordinating institutes to local communities and their institutions (see Blaikie, Citation2006; Mulale & Mbaiwa, Citation2012; Moswete & Thapa, Citation2015). These CBRNM approaches aim to empower communities to represent their interests with their own authority in planning and development processes (Thakadu, Citation2006).

Similarly as in the spontaneous participation, the core element in community empowerment is the idea of agency, i.e. that people are positioned as subjects in tourism planning and development processes (see Ramutsindela, Citation2009; Saarinen, Citation2012). Thus, in order to participate in fruitful and meaningful ways in tourism, communities need to feel empowered (Scheyvens, Citation2002; Thakadu, Citation2006; Mbaiwa Citation2017). For this, they also need to have an understanding of how tourism functions and what is the tourism system and its internal logic. This tourism awareness concerning its operations and impacts and what is community’s role in tourism is important for participation and benefit creation (Saarinen, Citation2010). It is an important because knowledge differences between industry actors and local people may involve power imbalances and lead to the cultural limits of participation (Tosun, Citation2000). Based on this Novelli & Gebhardt (Citation2007:449) have pointed out that local communities need to achieve ‘similar levels of understanding and knowledge’ with other stakeholders in order to fully participate in tourism planning and development processes (see Reed, Citation1997). Thus, full participation also calls for sharing of knowledge and learning (McCool, Citation2009), highlighting a need to raise community awareness in terms of collaborative tourism development (Moswete et al., Citation2009).

4. Local perceptions and attitudes towards changing environment and tourism development in Kang and Macheng villages

4.1. Study methods and research materials

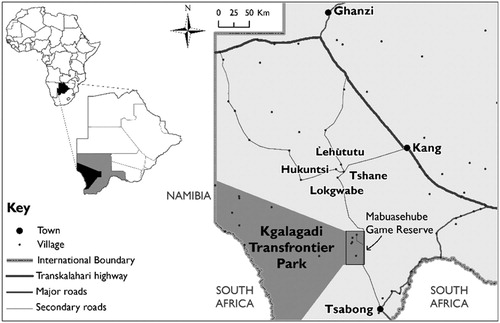

This study is based on research materials gathered from semi-structured questionnaires in May-June 2012, which were distributed in five villages consisting of Kang, Hukuntsi, Tshane, Lehututu and Lokgwabe in Kgalagadi North (). Of these villages, Kang is situated on the Trans-Kalahari Highway running through the southern section of Botswana linking up Botswana with Namibia and South Africa, while Hukuntsi, Tshane, Lokgwabe and Lehututu, known as Macheng villages, are more remotely located on the way to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (app. 80 km) from the Highway. Both Kang and Macheng villages have modest level tourism facilities (e.g. guest houses, bakeries, restaurants), but tourism is characteristically a passing by activity and/or based on short stops in the villages. There are no tourism statistics to support any estimates on the scale of visitation or characteristics of and expenditures by tourists.

Figure 1. Map showing Kang and Macheng villages (Hukuntsi, Lehututu, Tshane and Lokgwabe). Source: Data: National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency OpenStreetMap & MapCruzin. Map: Ms Outi Kivelä, Geography Research Unit, University of Oulu.

Semi-structured questionnaires were administrated face-to-face and respondents were approached in their homes. The questions aimed at soliciting respondents’ perceptions on experienced changes in the environment; key livelihood activities; replacement future livelihood activities; the contribution of tourism to community livelihoods; and community participation in tourism planning and development. The administration of the face to face questionnaires was based on a systematic sampling focusing on households in certain pre-selected wards (village districts). Although the sampling was systematic in this sense, the results cannot be fully generalised to community level(s) due to missing updated village-level population information. Based on (an outdated) 2011 census Kang (5985) is more populated than any single community in Macheng Villages (total 9393) (Statistics Botswana, Citation2012).

The sample consists of 289 residents and is quite evenly distributed among Kang (47. 2%) and Macheng villages (52. 8%). This resulted from an easier access to households in Kang as the structures of Macheng villages are a bit fragmented and, thus, more time consuming for empirical fieldwork. Therefore, despite the same time used in each sites, the sampling does not allow a direct statistical comparison between Kang and Macheng Villages as the samples represent differently the populations.

4.2. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents

A typical household representative was a female working in the household premises and having a relatively low level of education and income. Over one-third of the contacted households were actually female-led, and if there was an existing male household head he may have been working outside the house or village during the survey. Therefore, the majority of the contacted respondents are female (63. 2%) and there is no statistically significant difference in gender distribution between Kang and Macheng villages (). Over half of the respondents (51.3%) have secondary school level of education and the average household consists of 6.5 persons. It is notable that 50.0% of the contacted households received less than 1000 Pula (app. 90 USD) per month, which means that these households (and also the ones receiving max. 2500 Pula per month) are well below the current global poverty datum line of 1.90 USD per person per day. This interpretation is supported by the District level results of Botswana poverty mapping (Botswana Government, Citation2008) and the Botswana poverty incidence mapping (Majelantle, Citation2018).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents (N = 289).

As indicated in there are some differences on respondents’ age, income and years of residency depending on where they are from. In general, respondents from Macheng villages are older and have lived longer in their home community compared to the respondents in Kang.

4.2.1. Perceptions on environmental change, livelihoods options and tourism

Respondents’ opinions were distributed quite evenly concerning their experienced changes in environment during the past five years (). Based on the open-ended follow-up question (N=134), the main perceived changes were weather and rainfall related: weather patterns were seen as changing, temperatures getting warmer and rainfall was considered more erratic. These elements were perceived as causing soil degradation and droughts, impacting communities’ current livelihoods and their economic potential in future. A vast majority of respondents considered farming (arable and pastoral) as the main current economic livelihood (80.9%). Its prospects, however, were not seen positively as only less than 60% of respondents considered farming as the key livelihood for them in future. Based on their opinions it is challenging to identify a clear replacement livelihood, and this open-ended question did not position tourism in a visible role as it resulted in only very few mentions (in the category ‘Others’) from the interviewed community members.

Table 2. Local perceptions and preferences towards livelihoods options now and in future (N = 289).

Less than 2% of the respondents had received tourism-related income during the past year () which is understandable considering the estimated low tourist activities and employment at the time and perceived future. In respect to this almost missing personal participation in tourism operations and economy, there were no significant differences between Kang and Macheng villages. Similarly, only 2.5% of the respondents stated that some of their household members had received tourism-related monetary income in the past year, and a majority of the respondents (61.0%) had not even seen tourists in their communities (). Therefore, due to the minimal benefit creation based on the current level of tourism operations, almost all respondents (92.7%) had the opinion that the number of tourists visiting their villages and nearby area should increase, and they did expect to see tourism growth in future. None of the respondents had experience of participating in tourism planning and development processes.

Table 3. Local tourism knowledge and perceptions (N = 289).

In general, although most respondents or their household members have not received tourism-related income or even seen tourists, some did consider that there are certain community level benefits from tourism development. However, a majority (58.4%) of the respondents noted that there are no community benefits. Those that were of the view that the community does benefit from tourism listed the following main elements: general infrastructure development, income generation and employment creation. Respondents living in Macheng villages had a relatively strong opinion that there are no tourism-related benefits for their communities: almost two-thirds of them did not indicate any benefits from tourism, which indicates the role of expected proximity of tourism activities for local perceptions of tourism, its benefits and future potential. Furthermore, when asked as to who benefits from tourism, the Macheng respondents considered the government being the main recipient, while in Kang the respondents opined that the community is the main target for tourism-related benefits. In addition, foreigners (e.g. South Africans and Britons), their businesses and Batswana/citizens outside the villages were also considered among the main recipients of tourism-related benefits in the area.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Global environmental change and globalisation create increasing challenges for local communities to cope and adapt with changing socio-ecological environment. This is especially so in peripheral areas in southern Africa, such as the Kgalagadi region in Botswana, where communities are already facing environmental stressors and should proactively think how to cope with the change and develop and diversify their livelihoods in future (Moswete & Thapa, Citation2018). A proactive thinking of adaptive strategies and economic diversification is highly important with respect to the SDGs addressing challenges related to climate change-poverty nexus, for example. However, as noted by Atlhopheng & Segaetsho (Citation2019) one of the key challenges is how to implement the SDGs in a national scale and operationalise them for community development processes in practice in Botswana. In order to focus on the latter aspect, there needs to be information on how communities perceive the change and position themselves in the economic diversification policies, which are emphasising the increasing role of local participation and tourism in income and employment creation in the country.

Tourism is considered as having a good developmental potential in Botswana (see Moswete & Thapa, Citation2015) and in local development contexts, the prospective role of tourism is often portrayed very positively despite contextual challenges (Hambira & Saarinen, Citation2015; Saarinen et al., Citation2017). Based on this case study local people in Kang and Macheng villages were generally aware about the potential role of tourism growth in future. However, among the respondents, there was a missing involvement i.e. coercive participation in tourism operations, and this situation was further demonstrated by reported very minimal personal or household level benefits received from tourism. Furthermore, a majority of the respondents both in Kang and Macheng villages noted that they had never met and interacted with any tourists in their home village.

Still, over 40% of the respondents considered that tourism does benefit their communities. This indicates that there seems to be a difference between expected and experienced benefits from tourism: assumed tourism benefits were placed to community and government levels but they were not experienced as being delivered at personal or household levels. This may explain that despite the acknowledged need to diversity the current basis of livelihoods and local perception of tourism as an engine of economic growth in the region, the respondents did not consider the tourism industry as the replacement livelihood for them personally in future. Instead, no specified replacement economy was indicated, except ‘piece jobs’ that perhaps reflects an unsecured income and employment landscape for locals in future. All this indicates that tourism may have evolved in the area without an active integration to local communities and planning processes (see Mbaiwa, Citation2017) in which local people could have a say.

The study did not focus on the actual changes in the local environment, absolute impacts of tourism or local understanding of wider tourism economy or its operative logics in detail. These all would be interesting to analyse in future. In relation to tourism elements, it seems that poor local participation and access in tourism benefits and planning and the finding that a majority of the respondents had never actually met and interacted with any tourists indicates that their knowledge on the tourism industry and system are most probably quite limited. This lack of tourism awareness further hinders communities’ prospects to participate in and benefit from evolving tourism economy in the Kgalagadi region. In this respect, despite a strong emphasis on citizen power/spontaneous participation in tourism policies, there is a danger that the emphasised diversification of tourism spaces and products towards people and communities may actually turn people and their cultures to attractions for tourism without providing an agency and capacity to control the tourism growth. In cultural tourism development this lack of power may result in a benefit creation model serving more the industry than community needs in the diversification process (see Burns, Citation1999; Scheyvens, Citation2009; Saarinen, Citation2012). Thus, instead of being subjects, the communities may become objects for government and business operations in local development ingenuities.

It is clear that in order to benefit from tourism, community members need to be involved in the industry (Saarinen, Citation2019). Based on the results, there seems to be a long way to Tosun’s (Citation2000, Citation2006) induced and especially to spontaneous community participation, which obviously limits the potential of tourism to work for communities and SDGs in practice. Therefore, it is imperative to create and support those existing mechanisms which provide control and power for local communities to participate in tourism planning and development in a meaningful and mutually beneficial way, whose aims have been highlighted in recent inclusive tourism development and good governance literature (see Butler & Rogerson, Citation2016; Mbaiwa, Citation2017; Rogerson & Saarinen, Citation2018). These kind of inclusive and control mechanisms are often in place in wilderness and wildlife-based tourism operations based on CBNRM model (see Mulale & Mbaiwa, Citation2012; Hambira, Citation2019), for example, but village-based tourism development may call for new kinds of supporting and governance mechanism, which would provide an ownership for people on their culture, traditions and everyday living environment (see Moswete et al., Citation2009). Still, a further challenge is the existing poverty, as a minimum of two-thirds of the contacted households were below the poverty datum line. This means that the majority of the community members and households may not be able to adapt, but passively try to cope with the impacts of climate change and the changing socio-ecological environment of Kalahari Desert in future. All this calls for better governance of tourism planning and development that participates and, thus, empowers and benefits communities in the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adger, WN, Paavola, J, Huq, S & Mace, MJ, 2006. Fairness in adaptation to climate change. MIT Press, London.

- Adger, WN, Barnett, J, Brown, K, Marshall, N & O’Brian, K, 2012. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nature Climate Change 3, 112–7.

- Arnstein, SR, 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 35(4), 216–24.

- ASSAR (Adaptation in scale at semi-arid regions), 2015. Planning for climate change in the semi-arid regions of Southern Africa. Information Brief #1 http://www.assar.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/138/Info_briefs/ASSAR%20info%20brief%201%20-%20Planning%20for%20climate%20change%20in%20the%20semi-arid%20areas%20of%20Southern%20Africa.pdf Accessed 15 November 2019.

- Ashley, C & Maxwell, S, 2001. Rethinking rural development. Development Policy Review 19, 395–425.

- Atlhopheng, JR, Moshoeshoe, MG, Phunyuka, G & Mokgopa, W, 2019. Biodiversity and climate change perceptions in arid lands-implications for sustainable development in Botswana. Botswana Journal of Agriculture and Applied Sciences 13(2), 24–31.

- Atlhopheng, J & Segaetsho, T, 2019. UB SDGs Hub Technical Report 1 – public discussions on SDGs in Botswana. University of Botswana, Gaborone.

- Blaikie, P, 2006. Is small really beautiful? Community-based natural resource management in Malawi and Botswana. World Development 34, 1942–57.

- Botswana Government, 2008. Botswana census-based poverty map report: District level results. Botswana Government, Gaborone.

- Burns, P, 1999. Paradoxes in planning: Tourism elitism or brutalism? Annals of Tourism Research 26(2), 329–48.

- Butler, G & Rogerson, C, 2016. Inclusive local tourism development in South Africa: Evidence from Dullstroom. Local Economy 31(1–2), 264–81.

- Church, A & Coles, T, 2007. In Tourism, power and space. Routledge, Abingdon.

- England, MI, Dougill, AJ, Stringer, LC, Vincent, KE, Pardoe, J, Kalaba, FK, Mkwambisi, DD, Namaganda, E & Afionis, S, 2018. Climate change adaptation and cross-sectoral policy coherence in Southern Africa. Regional Environmental Change 18(7), 2059–71.

- Gentle, P & Maraseni, TN, 2012. Climate change, poverty and livelihoods: adaptation practices by rural mountain communities in Nepal. Environmental Science & Policy 21, 24–34.

- Grothmann, T & Patt, A, 2012. Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Global Environmental Change 15(3), 199–213.

- Gursoy, D, Chi, CG & Dyer, P, 2009. Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of Sunshine Coast. Australia. Journal of Travel Research 649(3), 381–94.

- Hall, CM, 2008. Tourism planning. Prentice-Hall, Harlow.

- Hambira W.L. 2017. Botswana tourism operators and policy makers’ perceptions and responses to the tourism-climate change nexus: Vulnerabilities and adaptations to climate change in Maun and Tshabong area, Oulu. Nordia Geographical Publications, 46(2), 1–59.

- Hambira, WL, 2019. A review of community social upliftment practices by tourism multinational companies in Botswana. In MT Stone, M Lenao & N Moswete (Eds.), Natural resources, tourism and community livelihoods in Southern Africa. Challenges of sustainable development, 52–63. Routledge, London.

- Hambira, W & Saarinen, J, 2015. Policy-makers’ perceptions on the tourism-climate change nexus: policy needs and constraints in Botswana. Development Southern Africa 33(3), 350–62.

- Hoogendoorn, G & Fitchett, JM, 2018. Tourism and climate change: A review of threats and adaptation strategies for Africa. Current Issues in Tourism 21(7), 742–59.

- Hunt, C, Durham, W, Driscoll, L & Honey, M, 2015. Can ecotourism deliver real economic, social, and environmental benefits? A study of the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 23(3), 339–57.

- Hunt, C & Stronza, A, 2014. Stage-based tourism models and resident attitudes towards tourism in an emerging destination in the developing world. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 22(2), 279–98.

- Kavita, E & Saarinen, J, 2016. Tourism and rural community development in Namibia: policy issues review. Fennia 194(1), 79–88.

- Kim, K, Uysal, M & Sirgy, MJ, 2013. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tourism Management 36, 527–40.

- Lenao, M & Saarinen, J, 2015. Integrated rural tourism as a tool for community tourism development: Exploring culture and heritage projects in the North East District of Botswana. South African Geographical Journal 97(2), 203–16.

- Lew, AA, 2014. Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tourism Geographies 16(1), 14–22.

- Li, WJ, 2006. Community decision-making: participation in development. Annals of Tourism Research 33, 132–43.

- Majelantle, A, 2018. Official statistics, trends and profile on poverty and inequality in Botswana. International Conference on leaving no one behind in the fight against poverty, exclusion and inequality, 20 March, Gaborone, Botswana. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/botswana/docs/Poverty/Session1/1.%20Anna%20Majelantle.pdf Accessed 1 May 2020.

- Masalila, P, 2019. Kalahari Conservation Society donates to cyclone Idai victims; KCS e-newsletter (July), 7–13. Gaborone. www.kcs.org Accessed 17 November 2019.

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2005. The socio-cultural impacts of tourism development in the Okavango Delta. Botswana. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 2(3), 163–85.

- Mbaiwa, J, 2015. Ecotourism in Botswana: 30 years later. Journal of Ecotourism 14(2–3), 204–22.

- Mbaiwa, JE, 2017. Poverty or riches: who benefits from the booming tourism industry in Botswana? Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35(1), 93–112.

- Mbaiwa, JE & Sakuze, LK, 2009. Cultural tourism and livelihood diversification: The case of Gcwihaba Caves and XaiXai village in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 7(1), 61–75.

- Mberego, S, 2017. Temporal patterns of precipitation and vegetation variability over Botswana during extreme dry and wet rainfall seasons. International Journal of Climatology 37(6), 2947–60.

- McCool, SF, 2009. Constructing partnerships for protected area tourism planning in an era of change and messiness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17(2), 133–48.

- Monare, M, Moswete, N, Perkins, J & Saarinen, J, 2016. Emergence of cultural tourism in Southern Africa: Case studies of two communities in Botswana. In H Manwa, N Moswete & J Saarinen (Eds.), Cultural tourism in Southern Africa: Perspectives on a growing market, 165–80. Channelview, Bristol.

- Mpandeli, S, Naidoo, D, Mabhaudhi, T, Nhemachena, C, Nhamo, L, Liphadzi, S, Hlahla, S & Modi, AT, 2018. Climate change adaptation through the water-energy-food nexus in Southern Africa. Environmental Research and Public Health 15(10), 2306.

- Moswete, N, Thapa, B & Lacey, G, 2009. Village-based tourism and community participation: A case study of Matsheng villages in southwest Botswana. In J Saarinen, F Becker, H Manwa & D Wilson (Eds.), Sustainable tourism in Southern Africa: Local communities and natural resources in transition, 189–209. Channelview, Clevedon.

- Moswete, N, Thapa, B & Child, B, 2012. Attitudes and opinions of local and national public sector stakeholders towards Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 19(1), 67–80.

- Moswete, N & Thapa, B, 2015. Factors that influence support for community-based ecotourism in the rural communities adjacent to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana. Journal of Ecotourism 14(2-3), 243–63.

- Moswete, N, Manwa, H & Purkitt, H, 2017. Perceptions of college students towards climate change, environmental, and tourism issues: A comparative study in Botswana and the US. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education 12(5), 349–58.

- Moswete, N & Thapa, B, 2018. Local communities, CBOs/trusts, and people–park relationships: A case study of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana. The George Wright Forum 35(1), 96–108.

- Mulale, K & Mbaiwa, JM, 2012. The effects of CBNRM integration into local government structures and poverty alleviation in Botswana. Tourism Review International 15, 171–82.

- Novelli, M & Gebhardt, K, 2007. Community based tourism in Namibia: ‘Reality Show’ or ‘Window Dressing’? Current Issues in Tourism 10(5), 443–79.

- Nunkoo, R & Gursoy, D, 2012. Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 39(1), 243–68.

- Nunkoo, R & Ramkissoo, H, 2011. Developing a community support model for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 38(3), 964–88.

- Nunkoo, R & Smith, SLJ, 2013. Political economy of tourism: Trust in government actors, political support, and their determinants. Tourism Management 36, 120–32.

- Paavola, J & Adger, NW, 2006. Fair adaptation to climate change. Ecological Economics 56(4), 594–609.

- Pearce, PL, Moscardo, G & Ross, GF, 1996. Tourism community relationships. Pergamon/Elsevier Science, Oxford.

- Pelling, M, 2011. Adaptation to climate change: From resilience to transformation. Routledge, London.

- Phuthego, TC & Chanda, R, 2004. Traditional ecological knowledge and community based natural resource management: Lessons for a Botswana wildlife management area. Applied Geography 24, 57–76.

- Ramutsindela, M, 2009. Transfrontier conservation and local communities. In J Saarinen, F Becker, H Manwa & D Wilson (Eds.), Sustainable tourism in Southern Africa: Local communities and natural resources in transition, 169–85. Channelview, Clevedon.

- Reed, M, 1997. Power relations and community-based tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research 24, 566–91.

- Rogerson, CM & Saarinen, J, 2018. Tourism for poverty alleviation: Issues and debates in the global South. In C Cooper, S Volo, WC Gartner & N Scott (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of tourism management: Applications of theories and concepts to tourism, 22–37. SAGE, London.

- Rylance, A & Spenceley, A, 2017. Reducing economic leakages from tourism: A value chain assessment of the tourism industry in Kasane, Botswana. Development Southern Africa 34(3), 295–313.

- Saarinen, J, 2010. Local tourism awareness: Community views in Katutura and King Nehale conservancy, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 27, 713–24.

- Saarinen, J, 2011. Tourism, indigenous people and the challenge of development: the representations of Ovahimbas in tourism promotion and community perceptions towards tourism. Tourism Analysis 16(1), 31–42.

- Saarinen, J, 2012. Tourism development and local communities: The direct benefits of tourism to OvaHimba communities in the Kaokoland, North-West Namibia. Tourism Review International 15(1–2), 149–57.

- Saarinen, J, 2019. Communities and sustainable tourism development: Community impacts and local benefit creation tourism. In SF McCool & K Bosak (Eds.), A research agenda for sustainable tourism, 206–22. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

- Saarinen, J, Hambira, W, Atlhopheng, J & Manwa, H, 2012. Perceived impacts and adaptation strategies of the tourism industry to climate change in Kgalagadi South District, Botswana. Development Southern Africa 29(2), 273–85.

- Saarinen, J, Moswete, N & Monare, MJ, 2014. Cultural tourism: New opportunities for diversifying the tourism industry in Botswana. Bulletin of Geography: Socio–Economic Series 26, 7–18.

- Saarinen, J, Rogerson, C & Hall, CM, 2017. Geographies of tourism development and planning. Tourism Geographies 19(3), 307–317.

- Scheyvens, R, 2002. Tourism for development: Empowering communities. Prentice Hall, Harlow.

- Scheyvens, R, 2009. Pro-poor tourism: Is there value beyond the rhetoric? Tourism Recreation Research 34(2), 191–6.

- Statistics Botswana, 2012. Population of towns, villages and associated localities. Department of Government Printing and Publishing Services, Gaborone.

- Telfer, DJ & Sharpley, R, 2008. Tourism and development in the developing world. Routledge, Abingdon.

- Tervo-Kankare, K, Kajan, E & Saarinen, J, 2018. Costs and benefits of environmental change: Tourism industry’s responses in Arctic Finland. Tourism Geographies 20(2), 202–23.

- Thakadu, OT, 2006. Success factors in community based natural resources management in northern Botswana: Lessons from practice. Natural Resources Forum 29, 199–212.

- Timothy, DJ, 1999. Participatory planning: A view of tourism in Indonesia. Annals of Tourism Research 26(2), 371–91.

- Thondhlana, G, Shackleton, S & Blignaut, J, 2015. Local institutions, actors and natural resource governance in Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and surrounds, South Africa. Land Use Policy 47, 121–9.

- Tosun, C, 1999. An analysis of the economic contribution of inbound international tourism in Turkey. Tourism Economics 5(3), 217–50.

- Tosun, C, 2000. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management 21(6), 613–33.

- Tosun, C, 2006. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management 27(3), 493–504.

- Totolo, O & Chanda, R, 2003. Prospects for subsistence livelihood and environmental sustainability along the Kalahari Transect: The case of Matsheng in Botswana’s Kalahari rangelands. Journal of Arid Environments 54, 425–45.

- United Nations, 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. United Nations, New York.

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organisation), 2008. Policy for the growth and development of tourism in Botswana. UNWTO/Government of Botswana Project for the Formulation of a Tourism Policy for Botswana, July 2008. UNWTO and Department of Tourism, Gaborone.

- UNWTO (World Tourism Organization), 2017. Tourism and the sustainable development goals – journey to 2030, highlights. UNWTO, Madrid.

- Willox, AC, Harper, SL, Ford, JD, Landman, K, Houle, K & Edge, VL, 2012. The Rigolet Inuit Community Government. Social Science and Medicine 75, 538–47.

- World Bank Group, 2017. World Bank Annual Report 2017. World Bank, Washington, DC.