ABSTRACT

Africa is rapidly urbanising and urban food systems are being transformed. Some have argued that this transformation is driven by a supermarket revolution akin to that in North America, Europe and Latin America. Others suggest that the supermarket revolution model oversimplifies complex African realities and that urban food systems are experiencing uneven supermarket penetration in the face of resilient informal food sectors. This paper focuses on Windhoek, Namibia, showing that the city’s food system is dominated by South African and local supermarket chains. Since the end of apartheid, South African supermarket chains have expanded their operations into Namibia. Supermarket domination of Windhoek’s urban food system is a function of proximity of South Africa and integration into South African supply chains. In other African countries, supermarket penetration has been much slower and is even being reversed. Explanations for uneven penetration in different countries require greater contextualisation and more case study research.

1. Introduction

Africa is urbanising at unprecedented speed and will be over 50% urbanised by mid-century (Parnell & Pieterse, Citation2014). Rapid urbanisation is being accompanied by major transformation of food systems (Reardon, Citation2015; Crush & Battersby, Citation2016; Tefft et al., Citation2017; Frayne et al., Citation2018), involving ‘extensive consolidation, very rapid institutional and organizational change, and progressive modernization of the procurement system’ (Reardon & Timmer, Citation2012). The process is driven by new urban mass markets, the growth of an urban middle class, and the activity of multi-national and local supermarket chains (Reardon, Citation2011; Tschirley et al., Citation2015). In the view of many, this amounts to a ‘supermarket revolution’ in the Global South (Reardon et al., Citation2003, Citation2007; Weatherspoon & Reardon Citation2003; Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006; Reardon & Gulati, Citation2008; Reardon & Timmer, Citation2008; Tandon et al., Citation2011; Dakora, Citation2012; Altenberg et al., Citation2016).

The idea of an inexorable supermarket revolution in Africa came to prominence after 2000 and was underpinned by four basic assumptions – first, the power of supermarkets in the Global North, and increasingly in Latin America, would inevitably diffuse in stages to Africa (Reardon et al., Citation2003, Citation2007). The modernisation argument that Africa is bound to follow the example of the Global North and experience a supermarket revolution is reinforced by the claim that the revolution proceeds in ‘stages’ with Africa the fourth stage (Dakora, Citation2012). Second, South Africa, whose entire food system has been revolutionised and dominated by a small number of supermarket chains, supposedly shows the rest of the continent a mirror of its own future. The aggressive expansion of South African supermarkets into the rest of Africa will hasten the realisation of an Africa-wide supermarket revolution by displacing other formal and informal forms of retail and their supply chains (Miller et al., Citation2008). Third, dietary change by Africa’s new and growing urban populations are providing new consumer markets that only supermarkets are equipped to meet. Spatially, supermarkets initially target middle-class consumers and higher-income areas but over time spread into lower-income areas with their mass market (Battersby, Citation2017). The final assumption is that the supermarket revolution presents new market and livelihood opportunities for the continent’s millions of smallholders who will be incorporated into modern food supply chains (Vorley et al., Citation2008; Biénabe et al., Citation2011).

The inevitability of a supermarket revolution across the continent has been questioned by a number of researchers who have challenged all of these assumptions. These researchers tend to focus on the obstacles that confront supermarket expansion in Africa, including the absence of large-scale commercial agriculture, inadequate transportation infrastructure, the lack of spending power of the mass of the urban poor, inhospitable regulatory and policy environments, and the strength of the informal food sector and other traditional forms of retail such as urban markets (Humphrey, Citation2007; Minten, Citation2008; Abrahams, Citation2009, Citation2011; Vink, Citation2013). Abrahams (Citation2009) suggests that proponents of the supermarket revolution model engage in ‘supermarket revolution myopia’ by neglecting other potentially transformative processes and the resilience of informal food economies in Africa. The transition towards supermarkets is therefore not a smooth evolution, nor does it entail the end of the informal food economy as ‘the growth and dominance of supermarkets presents only one element of a larger, more resilient narrative’ (Abrahams, Citation2009:123).

The resilience and growth of urban food markets, supply chains, and informal food vending has recently been documented in a number of studies in East Africa (Kirimi et al., Citation2011; Alarcon et al., Citation2017; Wegerif, Citation2017). Supermarkets have had considerable difficulty expanding their reach and still tend to cater for a small number of higher-income urbanites. In Southern Africa, a similar pattern can be seen in countries such as Mozambique, Zambia and Malawi (Tschirley et al., Citation2010; Mvula & Chiweze, Citation2013; Chikanda & Raimundo, Citation2016). Even in countries and cities dominated by supermarkets, including South Africa and Namibia, informal food retailing displays considerable resilience and supplies much of the daily food needs of lower-income consumers in general and those in informal settlements in particular (Battersby et al. Citation2016; Nickanor et al., Citation2019).

The assumption that smallholders will be integrated into, and benefit from, integration into supermarket supply chains has also been questioned. In the South African case, Karaan & Kirsten (Citation2008) note that

large food and agribusiness companies and large retailers are now dominant players in the South African agricultural and food system. This is replicating the situation in the high income industrialised nations of the world. Added to these realities are the low engagement levels of South African agribusiness and retailers with black farmers.

In the context of this debate between supermarket revolution advocates and sceptics, this paper focuses on the case of Namibia and the capital city of Windhoek in particular. A 2007–8 study of food security in Windhoek unexpectedly found that many households in low-income areas of the city were sourcing food from supermarkets (Pendleton et al., Citation2012). This finding suggested that supermarkets were playing an important role in the whole urban food system, not just in high-income areas of the city. Other research on supermarkets in Namibia has focused on supermarket supply chains and demonstrated minimal integration of rural smallholders into those chains (Emongor, Citation2009). However, little attention has been specifically paid to the activities and impacts of supermarkets in the Namibian capital undergoing rapid growth and change. This paper sets out to fill this gap in the literature on urban food systems in Africa by examining whether Namibia is following the path predicted by the classic supermarket revolution model or not and what role supermarkets play in the food system of the capital city.

2. Methodology

This paper uses primary research data drawn from three sources. First, consumer patronage patterns of supermarkets and other food retail outlets were constructed from a baseline household food security conducted in Windhoek in 2016. This city-wide survey sampled a total of 875 households using a two-stage sampling design. Primary sampling units (PSU) were randomly selected with probability proportional to size (PPS). The PSUs were selected from a master frame developed and demarcated for the 2011 Population and Housing Census. Within the city’s ten constituencies, a total of 35 PSUs was randomly selected and 25 households were systematically selected in each PSU. The sampled PSUs and households were located on maps, which were used to target households for interviews using tablet technology.

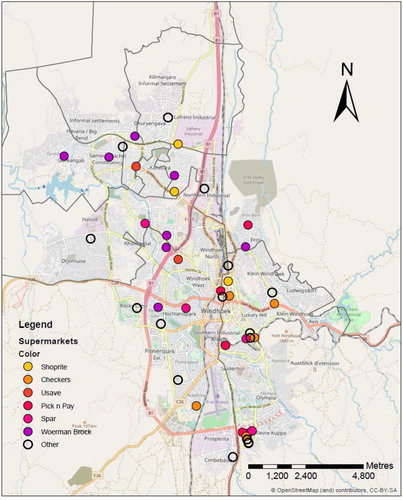

Second, a comprehensive inventory of all supermarkets in Windhoek was compiled from phone directories and field observation. The GPS coordinates of each supermarket were recorded, together with its name and company of ownership. This data was then plotted on detailed city maps of Windhoek and reduced to scale using GIS. The next step was to examine the socio-economic status of the constituencies in which the supermarkets were located. This was necessary in order to test whether supermarkets tend to cluster in higher-income areas or are evenly distributed throughout the city. This exercise facilitates analysis of whether the city is in the early or later stages of supermarket penetration of the urban food system.

Third, in order to assess the extent to which supermarkets were incorporating local suppliers into their supply chains, several supermarket managers were asked to share their product inventories and sourcing strategies. However, in each case, company policy prohibited the sharing of the information. A novel methodology was therefore devised to compile comprehensive product inventories in three supermarkets in different areas of the city (serving high, middle and low-income consumers, respectively). With the assent of managers, student research assistants photographed all products on supermarket shelves with cell phones, capturing information on product type, brand name, quantity, pricing, and source country. The information on the photographs was extracted and recorded in Excel spreadsheets for analysis.

3. Regionalising a revolution

South Africa’s food system is clearly dominated by supermarkets. Large-scale supermarket chains dominate the food retail market in most South African towns and cities (Battersby & Peyton, Citation2014, Citation2016; Caesar & Crush, Citation2016). Greenberg (Citation2017) notes that the transformation of the food system by supermarket corporations has involved extensive consolidation, rapid institutional and organisational change in agro-food value chains, and technological modernisation of procurement systems. There are now over 4000 large-scale hypermarkets and supermarkets in South Africa, and the number of branded convenience stores has increased to more than 4500 (Das Nair & Dube, Citation2017). The four biggest food retailers are Shoprite, Pick n Pay, Spar, and Woolworths. Combined, they control over two-thirds of the total South African food retail market. A fifth company – Fruit & Veg City (FVC) – has expanded rapidly, primarily marketing fresh produce (Das Nair et al., Citation2018). Two external players have recently entered the country: Walmart (who acquired a controlling interest in South African retailer Massmart) and Choppies (a Botswana-based chain).

The largest chain, Shoprite Holdings, has 1284 supermarkets (2016 figures) and a number of subsidiaries with different target markets, including Checkers, Shoprite, OK Foods, USave, and Hungry Lion. Pick n Pay operates 1280 supermarkets and hypermarkets in more affluent areas of cities, as well as the discount Boxer chain of supermarkets. The SPAR Group has 892 supermarkets and five brands – SuperSPAR, SPAR, KwikSPAR, SaveMor, and SPAR Express – using a franchise model of store ownership. Many of Woolworth Holdings’ 382 outlets (particularly in malls) retail clothing and housing goods along with food. FVC has almost 100 supermarkets in South Africa (Das Nair & Dube, Citation2015), including the up-market Food Lovers’ Market. Walmart primarily retails consumer goods but has started food retailing as Game FoodCo, and Cambridge (240 outlets combined). Choppies has nearly 70 supermarkets in smaller South African towns close to Botswana.

These supermarket chains have adopted the strategies of their North American and European forbears and counterparts, formalising supply chains and standardising supermarket layouts (Peyton et al., Citation2015). They have all invested in large distribution centres around South Africa, supplying products to outlets through their own or outsourced transportation companies. Centralised procurement drives down costs, reduces competition, and ensures that supermarkets can dictate terms to agricultural producers (Das Nair et al., Citation2018). It also lowers transaction costs, improves adherence to product quality and homogeneity, and reduces the number of suppliers who are retained on longer-term supply contracts. Supermarkets in South Africa initially served upper-income neighbourhoods and consumers, and in most towns and cities they still tend to cluster in suburban shopping malls or on main streets in the CBD. However, the supermarket chains are now increasingly targeting middle- and low-income residents of towns and cities, as well (Battersby & Peyton, Citation2016).

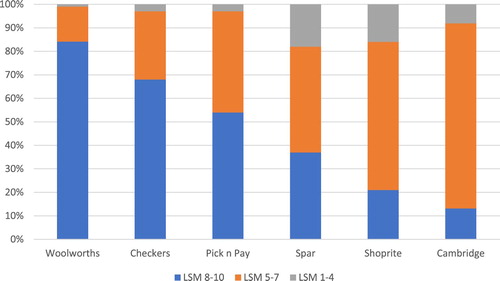

The budget subsidiaries of supermarket chains focus on the mass market in lower-income areas, often as anchor tenants in new mini-mall developments (Battersby & Peyton, Citation2014). As shows, the different chains have varying customer mixes when measured against the country’s LSM (Living Standards Measure) (see Truter, Citation2007). Woolworths, for example, draws 85% of its customers from the upper income LSM 8-10 brackets. Pick n Pay draws 54% from these brackets and 43% from middle-income LSM 5-7. Both have very few customers (less than 4%) in the low-income LSM 1-4 brackets. Spar has its most significant customer base in LSM 5-7 (45%) and a 15% presence among LSM 1-4 consumers. Shoprite-owned Checkers primarily targets high-income consumers (68% in LSM 8-10) with only 3% of its customers from LSM 1-4. By contrast, Shoprite (which includes USave) has 21% from LSM 8-10 and 16% from LSM 1-4. Its primary customers are middle-income earners (63% from LSM 5-7). Cambridge Food (launched in 2008), owned by Massmart-Walmart, has the lowest high-income customer share (13% in LSM 8-10) and the highest middle-income customer base (78% in LSM 5-7).

Figure 1. Customer base of supermarket chains in South Africa. Source: Nortons Inc. (Citation2016).

Battersby & Peyton (Citation2014, Citation2016) have mapped the spread of supermarkets across the urban landscape in Cape Town since the early 1990s and note that their spatial distribution remains highly unequal. The greatest concentration is in high-income areas, the CBD, and shopping malls along major transportation arteries. There are eight times as many supermarkets in upper-income quintile areas as in lowest-income quintile areas. They also map Shoprite’s USave supermarkets which target low-income consumers. USaves are disproportionately located on the edges of the poorer Cape Flats region which ‘has provided many in lower income neighbourhoods with a cheaper alternative food source’ (Peyton et al., Citation2015). Battersby (Citation2011) shows that 94% of households in three poor Cape Town neighbourhoods purchase some of their food at supermarkets. However, the frequency of supermarket patronage arise with income. Poorer households in most South African cities use supermarkets on a monthly basis to purchase staples (such as maize meal or rice) in bulk (Battersby, Citation2011; Rudolph et al., Citation2012; Caesar & Crush, Citation2016).

Since the end of apartheid in the mid-1990s, the major South African supermarkets have all aggressively sought out new markets in other African countries, leading some to conclude that Africa’s supermarket revolution is being led by South Africa (Dakora et al., Citation2010; Chidozie et al., Citation2014; Parker & Luiz, Citation2015; Das Nair & Chisoro, Citation2016; Das Nair & Dube, Citation2017; Das Nair et al., Citation2018). The penetration of supermarkets is part of a broader process of corporate South African profit-seeking in larger African markets (Miller et al., Citation2008; White & Van Dongen, Citation2017). Pick n Pay has 104 supermarkets and hypermarkets in eight other African countries (Das Nair & Dube, Citation2015, Citation2017). The Spar Group has 153 SuperSpar and Spar outlets in 12 countries while Woolworths owns food retailing outlets in 10 countries. Massmart-Walmart has Game outlets in 12 countries, although its Game FoodCo outlets are primarily located in South Africa at present. The most detailed information on geographical spread and the split between South African and other locations is available for Shoprite. As shows, Shoprite’s 171 non-South African outlets (or 84%) are spread across 14 African countries with a particularly strong presence in Namibia (26% of non-South African outlets), Angola (12%) and Zambia (12%).

Table 1. Shoprite holdings in Africa, 2015 (No. of supermarkets).

While the supermarket revolution model projects the inevitable spread of South African supermarkets into the rest of the continent, it did not fully take account of various obstacles and challenges to replicating the South African model in different regions, particularly those more distant from the country itself (Dakora & Bytheway, Citation2014). Dakora et al. (Citation2010) argue that cross-national systems connectivity, variable development levels of local production and supply, imports and freights, labour disputes/ issues, land issues in managing franchisees, complex international supply chains, import duties/paperwork, and domestic competition all present challenges for South African food retail expansion into other African countries. They categorise the barriers in supply chain expansion of South African retail businesses as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft.’ Hard barriers include those related to physical infrastructure and utilities. Roads, railways, ports, airports and electricity are the main delivery systems for retail companies to get their goods to outlets, yet this physical infrastructure is inadequate in many countries. Soft barriers comprise the bureaucratic environment of government legislation on imports and exports, and regional and international bilateral/multi-lateral trade and customs agreements. Other soft barriers include information deficits, land tenure rights issues, non-uniformity in regulations and market structures for freight/cargo, and protectionist policies of African governments (Dakora, Citation2016; White & Van Dongen, Citation2017; Das Nair et al., Citation2018).

While the spread of South African supermarkets to other countries is an indication of food system formalisation, the process has met with a mixed local response. Middle-class consumers have generally welcomed their advent, but their procurement and employment practices have generated considerable controversy and opposition (Miller, Citation2006, Citation2011). Abrahams (Citation2009), for example, notes that there have been concerted local efforts to discipline exclusionary sourcing practices and supermarket dominance. In Nigeria, farmers have threatened to burn down the South African owned Shoprite branch because of the supermarket’s practice of procuring food products from foreign sources (Abrahams, Citation2009). In Uganda, local authorities actively encouraged farmers to seek government support for what they referred to as ‘invading’ supermarket supply chains, helping producers meet the quality and consistency requirements for supplying the supermarket (Abrahams, Citation2009). Furthermore, Shoprite’s alleged practice of procuring 80% of their products from South Africa led the government of Tanzania to publicly condemn the practice (Ciuri, Citation2013). Shoprite’s expansion in East Africa has also been thwarted by local competition. In 2014, Shoprite’s locations in Tanzania were bought by the growing Kenyan retail giant Nakumatt (Ciuri, Citation2013). And in 2015, Nakumatt announced its intention to buy Shoprite stores in Uganda as well (Ciuri & Kisembo, Citation2015). However, Nakumatt itself has since run aground, reducing its number of outlets from 64 in East Africa at the beginning of 2017 to only 5 in mid-2018 (Kiriri Citation2018). The next section of the paper examines how South African supermarkets have avoided similar difficulties in neighbouring Namibia.

4. Windhoek’s urban food system

The urban population of Namibia increased from 493 000 (30% urban) to 1 116 000 (48% urban) between 1995 and 2015, and is projected to grow to 1 567 000 (55% urban) by 2025 (UNHABITAT, Citation2016). The growth of the capital city, Windhoek, has been particularly rapid: the population growing from 147 000 at independence in 1990 to 326 000 in 2011 to its current estimated 430 000. Rapid urbanisation has led to new demands for food and new markets for retailers. All of the major South African supermarket chains have developed a strong presence in Nambia over the last 20 years. Of the nearly 160 supermarkets in the country, one third are owned by Shoprite, followed by Pick n Pay (22%), SPAR (18%) and Woolworths (4%) () Of the South African chains, Shoprite and Spar are clearly the most important, with both expanding their national presence in Namibia in the last decade. The greatest growth has been from Pick n Pay (with 35 supermarkets since opening its first in 1997) (). Consistent with its corporate strategy of targetting smaller urban centres, Choppies has recently opened three supermarkets in northern Namibia, but none in Windhoek.

Table 2. Number of supermarkets in Namibia and Windhoek.

There is also one locally owned supermarket chain with a strong national and local presence: Woermann Brock (WB). WB originated as a German colonial trading company in the late 1800s and is still owned and run by the descendents of the founders. It opened its first supermarket in Windhoek in 1966 and has nearly 30 supermarkets throughout the country as well as six in Windhoek. Windhoek itself now has 45 supermarkets (or a fifth of all supermarkets in the country). Of these, half are South African-owned and half are locally owned. Shoprite has the largest South African presence in the city with 10 supermarkets (including two Usave, 3 Shoprite and 5 Checkers supermarkets). Woermann Brock has six supermarkets in the city.

The distribution of supermarkets in Windhoek is shown in . Although the spatial spread appears to be relatively even, most supermarkets are actually concentrated in higher-income areas. As shows, there is a direct correlation between the proportion of poor/severely poor and food insecure residents and the number of supermarkets in a constituency. At one end of the spectrum are Windhoek East and Windhoek West with no poverty and 30 supermarkets. At the other end is Moses Garoëb with 78% of residents living in poverty or severe poverty and only one supermarket. Shoprite subsidiaries such as Checkers are all located in higher-income areas of the city, as are direct competitors such as Pick n Pay supermarkets. Those supermarkets in lower-income areas tend to be Shoprite, USave and WB outlets. There are no supermarkets in the sprawling and growing informal settlements to the north of the city.

Table 3. Location of supermarkets by constituency.

Emongor (Citation2009) and Emongor & Kirsten (Citation2009) were the first to provide insights into the nature of supermarket supply chains in Namibia. Emongor (Citation2009) conducted a census of the source of products on supermarket shelves and showed the overwhelming domination of South Africa as a source of fresh food and vegetable products. She estimated that 82% of fresh fruit and vegetables came from South Africa and only 18% from local sources. Although supermarkets were required to source a certain percentage of their fresh produce from local farmers, most made up their quota by sourcing from a small number of large-scale commercial farmers. However, even these figures can be misleading. In 2014, for example, the Namibian Standards Institution launched an inquiry into mislabelling practices by several supermarket chains who were allegedly representing South African products as locally grown and produced (Kaira & Haidula Citation2014). Little, if any, fresh produce was sourced from smallholders, supermarkets claiming that the supply was unreliable and the quality insufficient.

With regard to processed foods, South Africa was again the dominant source. All of the brands of wheat and maize flour, and pasta were labelled as Namibian products. However, the processing ingredients were mainly imported and processed by a local milling company, Namib Mills. Emongor (Citation2009) reports that a government ban on the import of flour to Namibia meant that Namib Mills effectively had a monopoly on the importation and processing of wheat and maize to produce flour. Some 80% of all processed foods were imported from South Africa. The only locally procured foodstuffs were dairy and red meat. Most of the meat sold in supermarkets in Windhoek came from within the country with supply chains that connect supermarkets with large-scale commercial ranching operations via MeatCo, the largest abattoir in the country (Olbrich et al., Citation2014). Recent studies have highlighted the formidable barriers facing small-scale cattle farmers from accessing formal markets (Thomas et al., Citation2014; Kalundu & Meyer, Citation2017).

The cellphone inventory methodology developed especially for this study provided a more up-to-date picture of supermarket supply chains. All of the fruit and most of the vegetables in the supermarkets were labelled as products of South Africa. The exact locations in South Africa where these products are grown is not disclosed since aggregators such as FreshMark procure from throughout the country and supply supermarkets (including in Windhoek) via distribution centres. Some vegetables are locally produced by large irrigated farms. There was little evidence of procurement from smallholders. Red meat and fresh milk are labelled as products of Namibia, but again the supply is dominated by large-scale commercial ranchers.

Of the processed products inventoried, only 25% are manufactured in-country and 8% internationally (i.e. outside Africa) (). Two-thirds of products are manufactured in South Africa and imported. There are only three product categories – cereals and cereal products, dairy products and processed meat – where there are more local than imported products. In all other categories, there are more imported than locally produced products. Brands of flour and pasta are from Namib Mills, suggesting continuity with the findings from Emongor’s (Citation2009) earlier study. Rice packaged by Namib Mills is imported from Thailand and sold alongside Thai rice imported into South Africa where it is also packaged and re-exported to Namibia. As suggests, Shoprite’s supply chains for processed foods are dominated by imports from South Africa. That country has an almost complete monopoly on the supply of canned food, sauces, spreads, desserts and frozen foods.

Table 4. Source of foods in Checkers and Shoprite, Windhoek.

The high number of cereal products listed is related to South African domination of the supply of breakfast cereals. South Africa also has a commanding presence in the soft drinks (including fruit juices and pop), condiments (including tea and coffee) and snacks categories. There is very little sourcing from other countries within the region (with canned pineapples from Swaziland and orange juice concentrate from Zimbabwe the only recorded products). Equally, Europe and Asia are only sources for certain specialised foods. The only US product of the 642 different types on supermarket shelves is tabasco sauce.

5. Supermarkets in Windhoek’s food system

Given the large number of supermarkets in Windhoek, and their locational preference for higher-income areas of the city, we might expect this spatial unevenness to be reflected in differential patterns of consumer patronage in different parts of the city. However, over 90% of the surveyed households across the city purchase some of their food at supermarkets, far higher than for any other food source. A comparison of food secure and food insecure household food sourcing revealed little difference in overall levels of supermarket patronage (99% vs 96%). However, two-thirds of households only shop at supermarkets on a monthly basis. Another 17% shop at supermarkets weekly while only 5% are daily shoppers. This raises important questions about who purchases what kinds of products at supermarkets.

The household survey used the Hungry Cities Food Purchases Matrix to capture how many households had purchased a range of 30 separate food items in the previous month and where they get them from (Crush & McCordic Citation2017). shows the results for products purchased by more than 10% of households in the previous month. Every product on the list was primarily purchased at supermarkets by over 20% of households. However, when it comes to staples which are the main ingredient of household diets, the market domination of supermarkets is particularly clear. Over 90% of households purchasing maize meal, pasta, rice, and mahangu (millet flour) obtained these dietary staples at supermarkets. Supermarkets also completely dominated the market for dairy products (including fresh milk) and other necessities such as tea/coffee and cooking oil. Around 60% of purchasing households also obtained their meat and vegetables from supermarkets. Only four items on the list were purchased at supermarkets by less than half of the households: bread, fish, offal, and eggs. These products were certainly not absent from supermarket shelves but the informal food sector was an equally or more important source. In sum, supermarkets completely dominate the food retail system of Windhoek, irrespective of the location, wealth and level of poverty and food insecurity of households. At the same time, this does not mean the complete elimination of informal vendors who operate from fixed and informal markets, on the streets, and from tuck shops in informal settlements. In fact, the informal food sector is particularly important for households in informal settlements in meeting their daily food needs (Nickanor, Citation2014). Although the analysis here focuses on households as supermarket and informal sector patrons, it is also clear that informal vendors also regularly patronise supermarkets. They do this in three ways: first, they purchase in bulk and then bulk-break into smaller quantities for sale on the streets in markets. Second, they take advantage of inter-supermarket competition and sales by buying goods from supermarkets at reduced prices when they have product discounts. Third, they purchase goods for resale that are past their best before dates and are sold on by supermarkets at reduced prices.

Table 5. Main source of individual food items in previous month.

In order to assess the reasons why supermarkets were patronised in Windhoek, the most common reasons advanced in the literature for supermarket patronage were distilled into a number of statements for the over 90% of households who had shopped at supermarkets in the previous month to respond to. Some 88% agreed that the reason was the variety of foods in supermarkets (). Other factors with which there was strong agreement were the sales and discounts offered by supermarkets (82%), the better quality of food (81%), and the opportunities to buy in bulk (76%). The latter ties in with the tendency of many households to shop once per month for cereal staples in bulk. Supermarket prices were not nearly as strong an incentive for patronising these outlets: less than half (44%) agreed that food was cheaper at supermarkets and as many as 50% disagreed.

Table 6. Reasons for shopping at supermarkets.

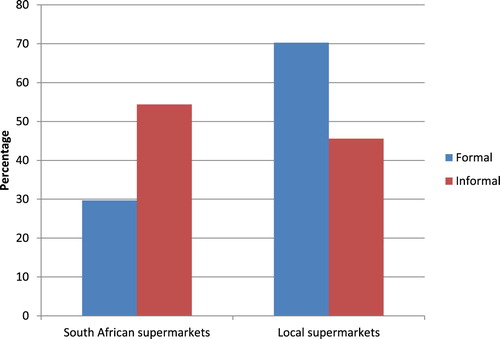

A final question that emerges from the supermarket revolution debate is whether local supermarket chains can compete with foreign-owned supermarkets. In terms of preference for South African over local supermarkets, over half of the survey respondents said they (57%) mainly patronise South African supermarkets, while the remainder (43%) patronise Namibian supermarkets (with 32% patronising WB). Shoprite is clearly the dominant South African chain, with two-thirds of the households patronising Shoprite, Checkers and Usave supermarkets. Around 17% shop at Usave (the subsidiary that targets lower-income areas of cities). The South African supermarkets appear to be more accessible than local supermarkets for households in informal housing where 54% patronise South African outlets compared to only 30% in formal housing. The majority of households (70%) in the formal housing areas shop at local supermarkets (). This suggests that although South African supermarkets are targeting higher-income areas of the city, they are attracting more customers in low-income and informal areas of the city. Local supermarkets tend to follow the more conventional strategy of targeting middle and high-income areas and consumers.

6. Conclusion

Many scholars have argued that Africa is undergoing a supermarket revolution, similar to that which had earlier come to dominate food systems and consumer habits in the Global North and Latin America. They suggested that South Africa is the one African country emulating this model and that South African-based supermarkets would lead a broader African revolution. The primary reason for this was the end of apartheid and the opening up of the continent to South African supermarket chains, who were attracted by the massive and growing urban consumer market accompanying rapid urbanisation and the growth of an African middle-class. The revolution would supposedly benefit consumers and small farmers who would be incorporated into new supermarket food supply chains. The proponents of the supermarket revolution model were primarily agricultural economists who viewed it as a largely inevitable and positive development. However, enthusiasm for the model has waned over time with much less being written about it in the last decade. Some have been extremely critical of the assumptions of the model (the idea of inevitable stages in particular), arguing that it overstates the power of supermarkets, ignores the many challenges they face in penetrating new markets, undervalues the resilience of the informal food sector and urban food markets, and that the primary beneficiaries are not consumers or smallholders but large, monopolistic corporations.

A study by the African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN) surveyed low-income households in eleven cities across the Southern African region and found surprisingly high rates of supermarket patronage not just in South Africa (Crush & Frayne, Citation2011). This finding broke with conventional wisdom at the time that supermarkets are primarily patronised by middle and high-income urban residents and therefore target those areas of the city where these residents tend to live. The AFSUN survey suggested that the supermarket revolution model was a potentially accurate depiction of countries in the immediate vicinity of South Africa. There were a number of reasons for this: first, those countries within the Southern African Customs Union and Rand Monetary Area facilitated the ability of South African corporations to do business, move goods across borders, and repatriate profits. Second, these countries had a long history of South African corporate investment dating back into the apartheid period. Third, geographical proximity meant that it was not necessary for supermarkets to build local supply chains from the ground up. Instead, these countries and their cities were simply incorporated into existing South African supermarket supply chains, becoming retail nodes for large-scale South African agricultural producers, food processors and retailers.

This paper has examined the nature of the supermarket revolution in Namibia in greater depth through a case study of the capital city, Windhoek. The levels of supermarket concentration in Windhoek are actually very similar to those in similar-sized South African cities. The Namibian supermarket revolution is incomplete in the sense that, unlike in South Africa, it has not involved wholesale transformation of the agro-food system as a whole. Some large-scale Namibian farms (particularly in the beef and vegetables sector) have been able to take advantage of new demands from supermarkets but the overall number of local producer-beneficiaries is small. Smallholders, in particular, have not been integrated into supermarket supply chains. Government protectionism has prompted some adjustment in supermarket strategies of procurement (particularly for processed cereal products) but, as this paper shows, the vast majority of supermarket products sold in supermarkets in Windhoek are imported from South Africa. Indeed, supermarkets in Windhoek appear to be fully integrated into the same supply and distribution chains as South African cities.

The purpose of the paper is not to resuscitate the idea of an Africa-wide supermarket revolution but rather to suggest that the model needs greater nuance and attention to the specific context of individual countries. There is growing evidence outside the region that urban food markets and informal vendors, and their supply chains, are extremely resilient and expanding their market share at the expense of supermarkets (Wegerif, Citation2017). However, it appears that the supermarket revolution is also proceeding rapidly in countries that are geographically proximate to South Africa. This is probably related to close geographical, historical and economic ties which mean that it is possible to seamlessly incorporate these countries into South Africa-based supply and distribution networks. Supermarket chains from the Global North do not have the same competitive advantage and are not present in countries such as Namibia as a result. In general, though, it is clear that there is no single unilinear supermarket revolution in Africa. Rather, the rate of supermarket penetration of urban food systems varies considerably from country to country. While some, such as Namibia, are aping South Africa, others are not or not to the same degree. More research is therefore needed to better understand the unevenness of supermarket penetration across Africa.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the research support of the Open Society Foundation for South Africa, the Hungry Cities Partnership (funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada) and the Queen Elizabeth Advanced Scholars program. We also wish to thank Gareth Haysom, Maria Salamone and the anonymous referees for their comments and input.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, C, 2009. Transforming the region: Supermarkets and the local food economy. African Affairs 109, 115–34.

- Abrahams, C, 2011. Supermarkets and urban value chains: Rethinking the developmental mandate. Food Chain 1, 206–22.

- Alarcon, P, Fevre, E, Murungi, M, Muinde, P, Akoko, J, Dominguez Salas, P, Kiambi, S, Ahmed, S, Hasler, B & Rushton, J, 2017. Mapping of beef, sheep, and goat food systems in Nairobi: A framework for policy making and the identification of structural vulnerabilities and deficiencies. Agricultural Systems 152, 1–17.

- Altenberg, T, Kulke, E, Hampel-Milagrosa, A, Peterskovsky, I & Reeg, C, 2016. Making retail modernisation in developing countries inclusive: A development policy perspective. Discussion paper 2/2016. German Development Institute, Bonn.

- Andersson, C, Chege, C, Rao, E & Qaim, M, 2015. Following up on smallholder farmers and supermarkets in Kenya. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 97, 1247–66.

- Battersby, J, 2011. The state of urban food insecurity in Cape Town. Urban Food Security series no. 11. AFSUN, Cape Town.

- Battersby, J, 2017. Food system transformation in the absence of food system planning: The case of supermarket and shopping mall retail expansion in Cape Town, South Africa. Built Environment 43, 417–30.

- Battersby, J, Marshak, M & Mngqibisa, N, 2016. Mapping the informal food economy in Cape Town, South Africa. Discussion paper no. 5. Hungry Cities Partnership, Cape Town and Waterloo.

- Battersby, J & Peyton, S, 2014. The geography of supermarkets in Cape Town: Supermarket expansion and food access. Urban Forum 25, 153–64.

- Battersby, J & Peyton, S, 2016. The spatial logic of supermarket expansion and food access. In Crush, J & Battersby, J (Eds.), Rapid urbanisation, urban food deserts and food security in Africa. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 33–46.

- Biénabe, E, Berdegué, J, Peppelenbos, L & Belt, J (Eds.), 2011. Reconnecting markets innovative global practices in connecting small-scale producers with dynamic food markets. Gower, Farnham.

- Blandon, J, Henson, S & Cranfield, J, 2009. Small-scale farmer participation in new agri-food supply chains: Case of the supermarket supply chain for fruit and vegetables in Honduras. Journal of International Development 21, 971–84.

- Caesar, M & Crush, J, 2016. Food access and insecurity in a supermarket city. In Crush, J & Battersby, J (Eds.), Rapid urbanisation, urban food deserts and food security in Africa. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 47–58.

- Chidozie, F, Olanrewaju, I & Akande, O, 2014. Foreign megastores and the Nigerian economy: A study of Shoprite. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5, 425–37.

- Chikanda, A & Raimundo, I, 2016. The urban food system of Maputo, Mozambique. Report no. 2. Hungry Cities Partnership, Cape Town and Waterloo.

- Ciuri, S, 2013. Nakumatt set to take over Shoprite stores in Tanzania. Business DailyAfrica, 17 December.

- Ciuri, S & Kisembo, D, 2015. Uganda: Nakumatt to buy Shoprite. All Africa, 23 July.

- Crush, J & Battersby, J (Eds.), 2016. Rapid urbanisation, urban food deserts and food security in Africa. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Crush, J & Frayne, B, 2011. Supermarket expansion and the informal food economy in Southern African cities: Implications for urban food security. Journal of Southern African Studies 37, 781–807.

- Crush, J & McCordic, C, 2017. The Hungry cities food purchases matrix: Household food sourcing and food system interaction. Urban Forum 28, 421–33.

- Dakora, E, 2012. Exploring the fourth wave of supermarket evolution: Concepts of value and complexity in Africa. International Journal of Managing Value and Supply Chains 3, 25–37.

- Dakora, E, 2016. Expansion of South African retailers’ activities into Africa. Project 2014/05. Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town.

- Dakora, E & Bytheway, A, 2014. Entry mode issues in the internationalisation of South African retailing. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5, 194–205.

- Dakora, E, Bytheway, A & Slabbert, A, 2010. The Africanisation of South African retailing: A review. African Journal of Business Management 4, 748–54.

- Das Nair, R & Chisoro, S, 2016. The expansion of regional supermarket chains and implications for local suppliers: Capabilities in South Africa, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Working paper 2016/114. UNU WIDER, Helsinki.

- Das Nair, R, Chisoro, S & Ziba, F, 2018. The implications for suppliers of the spread of supermarkets in Southern Africa. Development Southern Africa 35, 334–50.

- Das Nair, R & Dube, C, 2015. Competition, barriers to entry and inclusive growth: Case study on Fruit and Veg City. Working paper 9/2015. CCRED, Johannesburg.

- Das Nair, R & Dube, C, 2017. Growth and strategies of large, lead firms – supermarkets. Working paper 8/2017. CCRED, Johannesburg.

- Emongor, R, 2009. The impact of South African supermarkets on agricultural and industrial development in the Southern African Development Community. PhD thesis. University of Pretoria, Pretoria.

- Emongor, R & Kirsten, J, 2009. The impact of South African supermarkets on agricultural development in the SADC: A case study in Zambia, Namibia and Botswana. Agrekon 48, 60–84.

- Frayne, B, Crush, J & McCordic, C (Eds.), 2018. Food and nutrition security in Southern African cities. Routledge, London.

- Greenberg, S, 2017. Corporate power in the agro-food system and the consumer food environment in South Africa. Journal of Peasant Studies 44, 467–96.

- Humphrey, J, 2007. The supermarket revolution in developing countries: Tidal wave or tough competitive struggle? Journal of Economic Geography 7, 433–50.

- Kaira, C & Haidula, T, 2014. Checkers and Shoprite probed over mislabelling. The Namibian, 11 September.

- Kalundu, K & Meyer, F, 2017. The dynamics of price adjustment and relationships in the formal and informal beef markets in Namibia. Agrekon 56, 53–66.

- Karaan, M & Kirsten, J, 2008. A programme to mainstream black farmers into supply chains: an emphasis on fresh produce. Southern Africa policy brief 6. Regoverning Markets Project, IIED, London.

- Kirimi, L, Sitko, N, Jayne, T, Karin, F, Muvanga, M, Sheahan, M, Flock, J & Bor, G, 2011. A farm gate-to-consumer value chain analysis of Kenya’s maize marketing system. International development working paper no. 11. Michigan State University, East Lansing.

- Kiriri, P, 2018. The role of anchor tenants in driving traffic in a shopping mall: The case of Nakumatt exit from three shopping malls in Nairobi. Journal of Language, Technology & Entrepreneurship in Africa 10, 151–62.

- Michelson, H, Reardon, T & Perez, F, 2012. Small farmers and big retail: Trade-offs of supplying supermarkets in Nicaragua. World Development 40, 342–54.

- Miller, D, 2006. ‘Spaces of resistance’: African workers at Shoprite in Maputo and Lusaka. Africa Development 31, 27–49.

- Miller, D, 2011. Changing African cityscapes: Regional claims of African labor at South African-owned shopping malls. In Murray, M & Myers, G (Eds.), Cities in contemporary Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp. 149–72.

- Miller, D, Saunders, R & Oloyede, O, 2008. South African corporations and post-apartheid expansion in Africa: Creating a new regional space. African Sociological Review 12, 1–19.

- Minten, B, 2008. The food retail revolution in developing countries: Is it coming or is it over?. Economic Development and Cultural Change 56, 767–89.

- Moustier, P, Tam, P, Anh, D, Binh, V & Loc, N, 2010. The role of farmer organizations in supplying supermarkets with quality food in Vietnam. Food Policy 35, 69–78.

- Muchopa, C, 2013. Agricultural value chains and smallholder producer relations in the context of supermarket proliferation in Southern Africa. International Journal of Managing Value and Supply Chains 4, 33–44.

- Mvula, P & Chiweze, A, 2013. The state of food insecurity in Blantyre city, Malawi. Urban Food Security series 18. AFSUN, Cape Town.

- Nickanor, N, 2014. Food deserts and household food insecurity in the informal settlements of Windhoek, Namibia. PhD thesis. University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Nickanor, N, Crush, J & Kazembe, L, 2019. The informal food sector and cohabitation with supermarkets in Windhoek, Namibia. Urban Forum 30, 425–42.

- Nortons Inc, 2016. Grocery retail sector market inquiry: Pick n Pay submission. CCSA, Johannesburg.

- Olbrich, R, Quass, M & Baumgärtner, M, 2014. Characterizing commercial cattle farms in Namibia: Risk, management and sustainability. Working paper no. 248. University of Lüneburg, Lüneburg.

- Parker, H & Luiz, J, 2015. Designing supply chains into Africa: A South African retailer’s experience. In Piotrowicz, W & Cuthbertson, R (Eds.), Supply chain design and management for emerging markets. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 65–85.

- Parnell, S & Pieterse, E (Eds.), 2014. Africa’s urban revolution. Zed Books, London.

- Pendleton, W, Nickanor, N & Pomuti, A, 2012. The state of food insecurity in Windhoek, Namibia. Urban Food Security series no. 12. AFSUN, Cape Town.

- Peyton, S, Moseley, W & Battersby, J, 2015. Implications of supermarket expansion on urban food security in Cape Town, South Africa. African Geographical Review 34, 36–54.

- Reardon, T, 2011. The global rise and impact of supermarkets: An international perspective. Conference on the Supermarket Revolution in Food, Canberra, Australia.

- Reardon, T, 2015. The hidden middle: The quiet revolution in the midstream of agrifood value chains in developing countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 31, 45–63.

- Reardon, T & Gulati, A, 2008. The rise of supermarkets and their development implications. Discussion paper 00752. IFPRI, New Delhi.

- Reardon, T, Henson, S & Berdegué, J, 2007. ‘Proactive fast-tracking’ diffusion of supermarkets in developing countries: Implications for market institutions and trade. Journal of Economic Geography 7, 399–431.

- Reardon, T & Hopkins, R, 2006. The supermarket revolution in developing countries: Policies to address emerging tensions among supermarkets, suppliers and traditional retailers. European Journal of Development Research 18, 522–45.

- Reardon, T & Timmer, P, 2008. The rise of supermarkets in the global food system. In von Braun, J & Diaz-Bonilla, E (Eds.), Globalization of food and agriculture and the poor. IFPRI, New Delhi, pp. 189–214.

- Reardon, T & Timmer, P, 2012. The economics of the food system revolution. Annual Review of Resource Economics 4, 225–64.

- Reardon, T, Timmer, C, Barrett, C & Berdegué, J, 2003. The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85, 1140–6.

- Rudolph, M, Kroll, F, Ruysenaar, S & Dlamini, T, 2012. The state of food insecurity in Johannesburg. Urban Food Security series no. 12. AFSUN, Cape Town.

- Tandon, S, Landes, M & Woolverton, A, 2011. The expansion of modern grocery retailing and trade in developing countries. Economic research report no. 122. USDA, Washington, DC.

- Tefft, J, Jonasova, M, Adjao, R & Morgan, A, 2017. Food systems for an urbanizing world. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Thomas, B, Togarepi, C & Simasiku, A, 2014. Analysis of the determinants of the sustainability of cattle marketing systems in Zambezi region of north-eastern communal area of Namibia. International Journal of Livestock Production 5, 129–36.

- Trebbin, A, 2014. Linking small farmers to modern retail through producer organizations: Experiences with producer companies in India. Food Policy 45, 35–44.

- Truter, I, 2007. An overview of the living standards measurement. South African Pharmaceutical Journal 74, 52–4.

- Tschirley, D, Avieko, M, Hichaambwa, M, Goeb, J & Loescher, W, 2010. Modernizing Africa’s fresh produce supply chains without rapid supermarket takeover: Towards a definition of research and investment priorities. International development working paper 106. Michigan State University, East Lansing.

- Tschirley, D, Reardon, T, Dolislager, M & Snyder, J, 2015. The rise of a middle class in East and Southern Africa: Implications for food system transformation. Journal of International Development 27, 628–46.

- UNHABITAT, 2016. Urbanization and development: Emerging futures. UNHABITAT, Nairobi.

- van der Heijden, T & Vink, N, 2013. Good for whom? Supermarkets and small farmers in South Africa: A critical review of current approaches to increasing access to modern markets. Agrekon 52, 68–86.

- Vink, N, 2013. Commercialising agriculture in Africa: Economic, social, and environmental impacts. African Journal of Agricultural and Resources Economics 9, 1–17.

- Vorley, B, Fearne, A & Ray, D, 2008. Regoverning markets: A place for small scale producers in modern agrifood chains? Routledge, London.

- Weatherspoon, D & Reardon, T, 2003. The rise of supermarkets in Africa: Implications for agrifood systems and the rural poor. Development Policy Review 21, 333–55.

- Wegerif, M, 2017. Feeding Dar es Salaam: A symbiotic food system perspective. PhD thesis, Wageningen School of Social Sciences, The Netherlands.

- White, L & Van Dongen, K, 2017. Internationalization of South African retail firms in selected African countries. Journal of African Business 18, 278–98.