ABSTRACT

Since 2016 Ghana has introduced several initiatives to formalise parts of the e-waste economy. This e-waste management system is based on the experiences, expert policy advice and partial funding from the Global North. Employing serial interviewing, we assess the rolling out of this formalisation pathway, the evolving e-waste management landscape and reflect on informal terrain’s reconstitution and remaining barriers, such as inadequate funding, low levels of awareness about informal e-waste management among policymakers and the general populace and inadequate training programmes to equip informal operators with technology. Several formal/informal economy overlaps are now visible in a ‘gray space.’ Some low-skilled e-waste work, ancillary collection services and workplaces are being upgraded and integrated but informal infrastructure remains very deficient. Downgrading of some e-waste work is taking place. Fragmentation of the main hub is occurring as rival informal operations continue in various locations, and new small ventures are emerging in peripheral locations.

1. Introduction

The e-waste economy is today recognised globally as both strategic and lucrative. According to Baldé et al. (Citation2014:15), it forms part of the US$52 billion global electronics recycling and processing industry. The mobile phone repair, refurbishment, and reuse market segments account for a US$4 billion industry (Le Moigne Citation2017). Increasing recognition of the industry’s importance is also evidenced by several long-standing international management accords (e.g. Basel Convention, Bamako Convention), but informal e-waste economies still cluster in the Global South (Oteng-Ababio et al. Citation2020). The pervasiveness of informal e-waste recycling in developing economies with its territorial tendency and concerns over the release of toxins into the environment and human bodies at the processing locus have stimulated policy debate, media commentary, and non-governmental organisation (NGO) activism (Greenpeace Citation2008). These have culminated in international organisations and policy experts collaborating with governments to enact national legislation and formalise domestic e-waste management systems.

So far, some 40 countries have made headway in formalising their domestic regimes (Baldé et al. Citation2017:48). In the formalisation process, countries have turned to Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) principles, which require manufacturers to accept responsibility for all stages of product life cycles as the centrepiece of new domestic efforts (Baldé et al. Citation2017). Thus, in the Global North, e-waste is managed as part of a circular economy (keep materials in use and design to reduce waste), though the system is far from being a closed loop since a large amount of e-waste still gets diverted to distant ‘disadvantaged’ locations. In such locations (particularly in Africa), even though governments are aware of the heavy environmental and social costs inherent in poor e-waste management, only a handful of states (e.g. Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Rwanda, and Uganda) have so far adopted e-waste management bills (Baldé et al. Citation2017). Even in these countries, formal e-waste treatment facilities are meagre, hence planned ‘formal’ practices are emerging in a piecemeal process, aiming for international standardisation. However, questions are raised to as whether they are appropriate for contexts where the informal economy looms large (Grant Citation2019; Chen et al. Citation2020).

In Ghana, the government passed a formal E-Waste Management Bill (Act 917) in 2016 and a revised policy and Act is anticipated in 2021 (Quaye et al. Citation2019). Technically, the policy embraces the circular economy thinking, relying on formal companies to link with informal operators, although the concept is a virgin pathway in Ghana (Holland Circular Hotspot Citation2019:41). Our paper assesses the early evolution of the formal management system, its major players, its new formal infrastructure and particularly upgrades to informal infrastructure, and reflects on enduring barriers to informal participation. Given the new policy tilt, it is unknown if prevalent informal management systems are being supported or disabled, and/or whether the distinction between the dual economic sectors is breaking down or being worked out in other ways.

Barrientos et al. (Citation2010) rightly observed that though a new management system may enable upgrading of aspects of the e-waste value chain, the transition may also produce diverging trajectories. Thus, economic upgrading can entail social upgrading involving less discrimination, better working conditions, less vulnerability, and more empowerment and industrial voice but these advances take time and it is unknown when in the transition they are realised. However, the transition to formal management can also lead to economic downgrading of informal workers excluded from the restructuring, downward pressures on costs/remuneration dictated by lead firms (often headquartered abroad), and informal value chains cannibalised by formal firms, thereby adversely incorporating informal workers in another round of casualisation of employment. Other outcomes in the transition are also possible such as new cooperative arrangements based on new formal infrastructure (storage, transportation, treatment, disposal technological treatment) (Chen et al. Citation2020) in what has been labelled ‘the gray space’ (Lindell & Ampaire Citation2016), where a group of informal workers ally themselves with governmental or other actors, thereby engendering pragmatic and shifting web of relations that complicate neat division of informal versus formal entities.

2. Data and methods

Research on the formal sphere of e-waste in Ghana is scarce (notable exceptions are: Atiemo et al. Citation2016; Quaye et al. Citation2019; Chen et al. Citation2020; Oteng-Ababio et al. Citation2020). Prior research has concentrated on informal activities and related health, environmental and security consequences (Daum et al. Citation2017; Doyon-Martin Citation2015; Grant & Oteng-Ababio Citation2019), hence, the need for a probing methodology to assess its recent progression towards formalisation. In our view, ‘a one-shot interview’ common in social science research (to maximise sample size and a range of participants) is not capable of producing information of adequate quality, quantity and validity (Read Citation2018). As the management system evolves in scale and scope and as stakeholders respond to policy by changing practices, waiting on the side-lines, inaction and/or indifference to the formalisation pathway, one-off interviews fail to capture its influence. Indeed, single interview sessions in complex, ill-defined, occluded domains can produce a flattening of complexity as well as other bias such as interviewees’ giving safe, simple answers that reveal themselves in flattering lights and/or as victims (Read Citation2018). We employ serial interviewing (Crang & Cook Citation2007) (a number of interviews with the same respondents over a period of time) to uncover a panoramic view of interviewees’ learning and adaptation, degree of participation/nonparticipation in new initiatives, flexibility in forging new arrangements although they may be controlled by powerful firms (Williams Citation2019) as well as those remaining outside the formal management system in avoidance of the burden of policy reach. Serial interviewing provides an opportunity to explore the maturation of local knowledge, probe contradictory and inconsistent behaviour and reflect on existing barriers in the informal economy.

Our study also benefited from prior studies between 2009 and 2018 (see Oteng-Ababio Citation2010; Grant and Oteng-Ababio Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2019). This research proceeded in three steps. Step 1 involved listing the key stakeholders in the current e-waste landscape and their locations within the value chain and obtaining data through interviews and researching the internet to uncover newer entrants. Step 2 involved conducting semi-structured interviews with 10 formal firms (Blancomet Recycling, City Waste Recycling, FIDEV, Gravita Ghana, Success Africa Ghana, J. Stanley Owusu, Presank Enterprises, Vemark Environmental Services, Zoomlion, Zoil Services) and 20 environmental and government organisations (Customs and Excise, Environmental Protection Agency, Free Zones Board, Association of Ghana Industry, Agbogbloshie Scrap Dealers Association (ASDA), informal pickers, transporters, refurbishers, scrap dealers, and middlemen).

Given the evolution of this sector, a snowball technique was employed to identity key formal firms and importers, and we selected 10 of the 20 firms as a representative sample to elucidate the dynamic qualities of the major formal agents (Crouch & McKenzie Citation2006). Notes were taken during the interviews and were subsequently transcribed and repeat interviews were conducted to understand the complex dimensions of new management law and initiatives. The response rate was high, and only one formal firm decided not to participate. Questions posed in interviews related to the introduction of the management bill, intent to deploy technologies, participation/nonparticipation in new management initiatives and the likely impact of an upgraded formal Agbogbloshie Recycling Centre (ARC). Key agents were interviewed on several occasions (during June 2017, December 2018 and again in June 2019) in a serial interviewing approach (Crang & Cook Citation2007; Read Citation2018).

3. Sketching the background and the shadow of Accra’s E-waste informal economy

The Accra e-waste industry is an important informal activity supporting a large, well-organised informal livelihood subdivisions and self-governance centred around refurbishment and recycling (Grant & Oteng-Ababio Citation2013, Citation2019, Stacey Citation2019). While the sector has grown and consolidated, it remains technically ‘brittle,’ since each node in the value chain can be disrupted by either state intervention (policy supports and/bans), market forces (price fluctuations, intermittent flows, or/and intense local competition), vagaries of the quality and quantity of imports, and export demand for its constituent valuable fractions. Despite relying on low-level technologies and manual labour, a variegated division of labour occurs. After importation and wholesaling, the e-waste value chain encompasses five conduits along through which value recovery and new value creation occur: (1) resale, (2) refurbishing, (3) repair (4) dismantling, and (5) secondary inputs. The first three conduits are situated in the informal economy and intersect with second-hand market buyers who cherry pick the most saleable items. Large electronic importers participating in both new and used trade (e.g. CompuGhana, Zepto, Next Computers) maintain ties to both formal and informal circuits (Atiemo et al. Citation2016). Formal firms control the accumulation and trading of secondary metals for reincorporation into manufacturing production whether in Ghana (e.g. copper smelting in Tema) or elsewhere (Grant & Oteng-Ababio Citation2016).

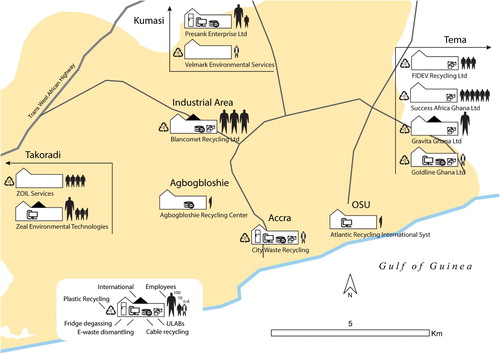

A major e-waste hub is Agbogbloshie, Accra. On site, most entry-level tasks are undertaken by marginalised migrants from northern Ghana who cannot find other decent work; they gravitate to informal e-waste collection and pre-processing because it offers same-day payment and ease of entry. The challenges notwithstanding, participants collect 95% of e-waste generated nationwide (Grant & Oteng-Ababio Citation2016). They operate a low-cost, efficient household collection and treatment in informal workshops mainly at Agbogbloshie. Various estimates of the size of this e-waste exist. Prakash & Manhart (Citation2010:15) for example estimate about 4,500–6,000 individuals are employed directly and approximately 30 000 throughout the broader e-waste chain of activities, with as many as 200 000 livelihoods sustained nationwide (Oteng-Ababio et al. Citation2014:164). Another 400–600 informal recycling firms operate in Accra, all with strong ties to scavengers (see ). Subsets of these firms are linked to formal firms, but most scrap operators are survivalists and depend on intermediators. Economically, the e-waste economy contributes about 0.55% of Ghana’s GDP (Prakash & Manhart Citation2010:38), which the World Bank (Citation2015:41) calculates to be about US$416 million.

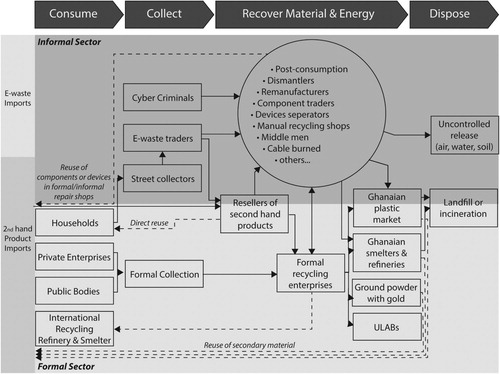

represents the network and flows of e-waste materials within Ghana. Shading in the diagram designates informal circuits moving to and from formal circuits in the recycling chain. In real-time operation, there is always no clear split between the two sectors as they often overlap and sometimes highly relate to each other. In terms of processes, the obsolete electronic products are sold to the informal sector where components (power supply cables, compressors, etc.) and devices (handsets, processors) are dismantled and segregated. Regarding material-specific recovery and separation (e.g. copper, lead), they occur after manual separation, and after grading these fractions which enter the secondary-materials market.

Figure 1. E-waste players and ties in the formal and informal economy.

Note: Figure 1 is adapted from Chi et al. (Citation2011:737).

Data on imports of new and used categories of electronics is shown in . Over the ten-year period, 302 000 tonnes of electronic goods were imported. Large household appliances account for almost half of the volume in weight, and used appliances are the norm in several product categories (e.g. air conditioners, refrigerators, radios, and stereos). Second-hand imports provide some indication of the amount of e-waste: World Bank (Citation2015:37) estimates this to be 110 000 tonnes.

Table 1. Top 10 used-electronics imports in tonnage volumes, Ghana 2010–18

4. Shifting terrains

In 2010 monthly estimates of second-hand electronics shipments to Ghana were estimated in the range from 300–600 containers per month arriving at the port of Tema (Amoyaw-Osei et al. Citation2011) and smaller amounts arrived by land from neighbouring countries (Grant & Oteng-Ababio Citation2016). A senior Ghana Customs and Excise official interviewed on several occasions emphasised in June 2019 that even if earlier estimates were correct, ‘these days are now gone’ and e-waste imports ‘have been in sharp decline since 2017.’ In practice, e-waste imports are at the interface/grey area between illegal smuggling and legal import (Wang et al. Citation2020). At the same time, mounting evidence indicates that domestic sources are on the rise, amounting to 1.4 kg per capita or 39 kt in 2016 (Baldé et al. Citation2017:104). The shift towards domestic sources of e-waste may mean management might become more clear-cut.

In recent years, the government is actively seeking to dispel the negative image of Accra as a ‘wasteland’ (Oteng-Ababio & Grant Citation2019), leveraging international funding and technical support to clean up the sector. Facilitating this progression, the government is the beneficiary of several European funding streams: e.g. EU funding of €1.2 million (2018–2022) to formalise micro enterprises, disseminate best practices, and provide training (EU Citation2018); German government (€25 million) support to provide technical assistance; Swiss funding of €6.1 million (2020–23) for sustainable recycling of e-waste, including an initiative to teach informal recyclers to extract copper more efficiently without burning devices (Ngounou Citation2020), and the Dutch government and five local companies are attempting to facilitate the local circular waste economy (Holland Circular Hotspot Citation2019:35). Further, the e-waste sector is also supported by the Society General de Surveillance SA, a Swiss company with expertise in surveillance, verification, testing, and the collection of eco-levies (Kumi et al. Citation2019).

While pressures to curb some informal activities are ongoing in the policy arena, initiatives are scattered and far from reflecting an integrated policy framework. The government established a formal recycling centre (e.g. ARC) for the safer handling of cables and a Handover Centre (comprising of modified and repurposed 40-foot shipping containers arranged in a U-shaped square with doors/windows plus an additional roof covering to prevent overheating of the inside workspace). Lauded in the Ghanaian press and social media (Dogbevi Citation2016), an upgraded and expanded centre was inaugurated in March 2019, located in the heart of Agbogbloshie. Supported by German funding (€5 million), this facility aims to kickstart sustainable e-waste management. Providing a designated building, storage and secure area (the latter alleviates materials theft), technical support (facilitated by local NGO, Ghana Advocacy, who provides training in cable stripping and the shredding of plastics), advisory services, and in-house health services for 100 workers is a significant improvement, especially for those hitherto unprotected, informal workers. Material deliveries are also supported by onsite motorcycle-taxi vehicles (okada), thereby involving other informal workers. The designated roofed facility goes some way in removing the stigma of dirty, polluting, and undesirable activities and acknowledges this work as legitimate, environmentally sound, and safe for its affiliates. One interviewee commented that his ‘uplifted role will be a hinge that links the big players to the small players’ (Interview, December 2019).

The municipality has been active in rehabilitating key spaces in Agbogbloshie for some time (see Oteng-Ababio & Grant Citation2019 for detailed discussion). But past municipal actions suggest that formalising the sector competes with other policy objectives. For example, a clean-up exercise to prevent flooding cleared a 50-metre channel along the Korle Lagoon in 2015 and resulted in forced evictions and shack demolitions. Subsequently, the municipality dumped rubble around the scrap yard in an effort to deter the rebuilding of temporary structures. For a period of time the government located a waste station in the same vicinity. More recently, the largest waste management company, Zoomlion, has stationed its Integrated Recycling and Compost Facility in the area. Zoomlion further partnered with the municipality to clean up the area and sensitised traders and patrons about keeping the market area clean (Interview, December 2018). Such attempts to coordinate this central space have not, however, succeeded in greatly changing negative perceptions by the public and industries about e-waste in this area. Indeed, Agbogbloshians remain deeply suspicious that cleaning up the negative aspects of e-waste may reflect ‘ulterior motives’ and that ‘the government is making way for future urban redevelopment in this central location, (likely to be lucrative for those involved because of the central location), (Interview, December 2018 and even more forcibly argued in June 2019) despite setting up several new initiatives in the vicinity.

An uptake in international recycling organisations assisted by international NGOs, facilitating new roles for some informal operators is also evident. For example, a social entrepreneurship intervention known as the Agbogbloshie Makerspace Platform (AMP) aims to generate alternative income and to amplify informal participant workers’ reputation as ‘makers’ (AMP Citation2017:1). This youth entrepreneurship project engaged about 75 informal workers in refashioning e-waste – wires and cables become bracelets; radiators become pots; oil drums and refrigerators become grills. Such upcycling focuses on transforming e-waste into consumer commodities and objects of art, hopefully tapping into a new market niche. However, after the initial three years of funding, this project ran into difficulties because it did not become self-sustaining. Despite AMP being longlisted (but not selected) for a 2019 Visible Award to retrofit the scrapyard in a participatory initiative linking ‘makers’ with STEM professionals, in 2020 it is almost dormant due to a failure to procure additional funding. Nevertheless, AMP is indicative of the kind of a short-term grassroots intervention supported by external donors that provides some support in the transition towards formalisation.

Different pilot schemes have also experimented with formalising take-back services. For example, Ericsson, Sweden, ran a pilot take-back scheme in 2014 to recover 100 000 obsolete mobile phones without much success. Fairphone, a Dutch sustainable smartphone company, has also operated a recycling scheme since 2014, collecting three tons of waste phones using a local partner, Recell (Fairphone Citation2017: 1). Even the government in 2018 became the first African country to release technical guidelines for the collection, treatment and final disposal of e-waste (SRI & EPA Citation2018). Such efforts notwithstanding, formal take-back public infrastructure remains non-existent in Ghana while informal operators continue to dominate the e-waste collection turf. Parallel to these developments, imports of new low-cost electronic units from China and UAE have surged, while the used market has softened; repairers noting, ‘customers failing to collect/pay for repaired items, causing storage and business problems’ (Interview, December 2018 and reiterated again in June 2019). Thus, the real battle is not just about formalisation but to ensure that the legislation does not morph into a greenwashed environmental pact between international regulators and environmental NGOs.

5. The domestic formal economy

Many scholars (e.g. Wang et al. Citation2020) contend that the lack of sound international regulations is the main reason that e-waste is transported to Ghana. The government has long been aware of the phenomenon and official attitude was one of acquiescence until recent years.

Since the early 2000s formal foreign firms (Success Africa, Gravita, Commodities Processing, and N.N. EST Metals; Goldline), have been operating from the Tema export processing zone (EPZ) (and a few others [e.g. Blancomet}, operating outside), enjoying sole rights to export scrap metals (2004–10). In recent years more formal firms have entered the e-waste arena downstream (Atiemo et al. Citation2016). Some 20 formal, registered companies now operate across the waste and electronic recycling value chain (from collection to processing to exporting to secondary lead smelters). Firms are becoming more proactive and no longer restricting their activities to one stage in the value chain, instead increasingly straddling two or more stages (focusing on more waste streams/service offerings and engaging in complementary activities; e.g. export and/or recycling). But formal firms cannot compete with informal operators in collection/preprocessing due to higher operating costs when abiding by environmental/labour laws.

E-waste is only profitable as a stand-alone business for the largest formal firms concentrating on exports (Interview export firm, June 2017; June 2019). Most formal firms regard it as a secondary activity, largely unprofitable to date (Interview export firm, June 2019). Outside of exporting, most profits are secured in the informal economy via metal accumulation, middlemen trading, and some aspects of refurbishment (Interviews, June 2017; June 2019), although this situation appears to be changing since more affordable electronics are entering the market in greater quantities. The formal e-waste sector is not a large employer. For instance, Blancomet Recycling, one of the largest players, employs 300 workers in its entire (diverse) e-waste activities, yet most are employed on contract or subcontract basis. Most private companies’ (e.g. Zoomlion) core activities focus on solid waste; typically, less than 5% of employees participate in e-waste-related activities. Large firms’ main output fractions ‘are ferrous (50%), non-ferrous (16%) and printed circuit boards (16%)’ (World Bank Citation2015:8), and in addition complex fractions are ground down for sophisticated mechanical processing abroad.

Some local firms are struggling to enlarge their e-waste foci (e.g. recycling acid batteries, refrigerator degassing, cable recycling, and e-waste dismantling), in most cases, supported by international funding. For example, City Waste Recycling received German government funding to purchase a cable granulator to separate and recycle copper, and the firm is considering building a two-hectare state-of-the-art recycling plant (Interview, December 2018), but it has not been built to date. This upturn in formal firms’ e-waste engagement also extends to the largest firms devoting more time and effort to research additional business opportunities, anticipating green funding to support potential exploratory projects. Ghana’s formal firms are positioned in the value chain where profits are stable and health risks minimised. These firms are linked upwards to international processors and refineries and linked downwards to the metals buyers. An interviewee from the ASDA in December 2019 described the Agbogbloshie informal hub as functioning ‘in a closed and circular system in which resources and waste are neither the beginning nor the end of a process and in which nothing appears or disappears’.

6. Formalisation and the policy environment

The government of Ghana is acting to formalise e-waste with a top-down focus on management, largely through new legislation accompanied by capital-technical initiatives underwritten by international partners. Initially, the E-Waste Management Bill aimed to ban both imports and exports of e-waste. However, its text affirms support for the Basel Convention, so it permits conditions under which hazardous waste can be imported. Thus, a formal company can apply to be granted the right to import hazardous waste, and imports are permissible if the entity can manage and dispose of the waste in an environmental-friendly way.

The government seeks to corral e-waste space by stricter official control. Public authorities are empowered to order ‘the sealing up’ of any ‘area, site or premises’ suspected to be a place for hazardous waste disposal (Government of Ghana Citation2016:3). The officers are granted ‘a power of search, seizure and arrest, over person or place suspected of keeping or transporting hazardous wastes. Searchers that fall under the auspices of governmental powers include vehicles, lagoons, ponds, landfills, building, structures, storage containers and ditches’ (Government of Ghana Citation2016:2). This vaguely configured authority further legitimises the persecution of informal waste collectors, already subject to harassment, hostility, and seizures by municipal authorities and has considerable discretionary powers to disable informal operators deemed in violation of the law.

The Ghanaian regulationist approach fails to disaggregate the informal economy and targets particular collectors and preprocessors such as those engaging in burning, illegal dumping, and disorderly storage in the Agbogbloshie area, some of the most visible and precarious players. The policy tilt assists larger formal companies and networks then to secure loans to purchase equipment from international governments (e.g,. Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and organisations (e.g. Pure Earth)). At the other end, the bill relies on Ghana’s Environmental Protection Agency to disarm informal operators and close sites, while municipalities are authorised to close e-waste markets and ban informal collectors’ pushcarts from the streets. Sporadic enforcement, virtually non-existent monitoring and auditing remain considerable barriers to formal management. To replace the informal system, the bill establishes state-led collection, but the state’s meagre formal-informal scheme centred on Agbogbloshie barely makes a dent on the informal sector. Informal collectors are more competent than their formal counterparts, given their door-to-door collection service, convenience, extensive collection categories of waste and amounts paid to customers. Rather than incentivising manufactures and importers to develop efficient closed-loop systems and foster sustainable relationships with informal waste collectors and incentivising informal operators to green their activities, the legislation depends too much on state control and bolstering established formal companies’ leverage in the market.

Ghanaian realities are overlooked and much of the informal sector remains a blind spot. The informally connected vertical parts of the non-formal economy where tight social relations prevail is undervalued. Dynamic relationships exist (e.g. between aggregators and repairers) with an awareness of each other’s supplies (Kumi et al. Citation2019). Aggregators visit repair shops (many are located in garages and backyard premises) to enquire about non-repairable gadgets; repairers call on scrap yards to source specific components for particular jobs. The vast majority of these workers remain ineligible for loans due to the informal nature of their trade, poor record keeping, and ‘because lending institutions perceive them as risky’ (Interviews, December 2018). Intermingling of e-waste and other scraps is common. Without incentives to green the least profitable informal economy tasks, it will be business as usual and out of sight out of mind for any kind of policy support.

As portions of the informal economy are being reconstituted by new formal experimentation in shared infrastructure (e.g. the ARC/Handover hub), the informal economy is being further fragmented away from Agbogbloshie to secondary sites in Accra (e.g. Ashaiman in Tema and Madina in northeast Accra) and to various minor sites throughout the city and beyond (e.g. Kumasi, Koforidua, and Takoradi). Scattering of the Agbogbloshie informal hub has also occurred due to other political factors.

Political shifts and the election of a new President in 2017 of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) also coincided with a parallel shift in leadership of the Agbogbloshie informal hub that saw affiliates of the NPP assume leadership, while loyalists of National Democratic Congress (NDC) were purged from the site. Interviews with informal recyclers in Agbogbloshie (December 2018/June 2019) emphasised a deep politics whereby national political swings coincide with a corresponding adjustment in the leadership of the Agbogbloshie recyclers. For instance, ARC’s establishment, therefore, reinforced the political split and in essence added another layer of complexity as multiple circuits continue to operate in different locales. NDC loyalists relocated to a separate but proximate site along Abose-Okai Mortuary Road. Moreover, field observations confirmed a further labour and site fragmentation driven by efforts to reduce transport costs and to avoid all politics associated with the restructuring of e-waste at the hub. Unknown to the public is the proliferation of informal processing across the urban periphery, distant from ethnic/political cleavages that run deep in Agbogbloshie, where conflicts involving the Dagbon chieftaincy in the northern region are extended, spill over, and sometimes erupt in violent episodes, machete fights, and even local killings (Interviews, December 2018/June 2019).

Upgrading has occurred for some workers affiliated with the ARC buy-back centre (collectors, pickers, transporters) that especially managers/opinion leaders that link directly to formal firms and funding organisations that purchase technological equipment and decide on who participates in training schemes. However, downgrading is also occurring in that other workers have been side-lined in this area and less opportunities exist for new nonskilled entrants into the sector at the main hub. In yet another round of informalisation, there is evidence of more non-affiliated informals operating from peripheral locations beyond the purview of formal management and surveillance. However, it is impossible to determine that extent to which this a direct consequence of the evolution of formal management infrastructure and/or the precarious reality for survivalists in an economy where employment options are scarce. Several middlemen who hitherto acted as gatekeepers now find themselves cut from some markets as well. As a consequence, these middlemen have responded by forging new arrangements with start-ups in peripheral locations. Start-up operations in the periphery have the least room for manoeuvrability, fewest prospects of upgrading, and greatest likelihood to experience downward business pressures due to their relative isolation and lack of accumulated knowledge, particularly about the transition to formal e-waste management.

Whether ARC will be a strong anchor (leading the way in best practices that can be scaled-up and/or cannibalise the informal economy) or a weak link in the new management chain (providing decent work for affiliates but otherwise not upgrading skills/value), is still unclear.

While ARC is a start, it is a modest facility, wholly insufficient to accommodate numerous informal operators based in garages, makeshift sheds, and other unauthorised spaces scattered across urban areas. Various initiatives to manage e-waste remain uncoordinated and non-integrated, reflecting a scattergun approach that follows international funding rather than a coordinated, sequenced, local strategic plan, with broad-based participation, not just from the community and informal workers but also from the public. Moreover, while associations and various informal business networks exist (ASDA renewed its registration in 2019), cooperative groups in e-waste in Ghana are rare, and industry associations and/or classifications of e-waste activities along the chain conceal huge variability. External interventionist projects, no matter how advocated by government and its partners, remain at high-risk of not achieving a long-term impact due to combinations of factors such as political commitment challenges in the context of limited resources, local and national politics, corruption, and failure in building local capacity among informal operators.

7. Ghana’s E-waste management pathway evolution: concluding remarks

The government’s top-down regulationist management approach privileges the more powerful firms, and silences others and when informals are included (to work more safely, efficiently and more environmentally sustainable) their articulation with formal firms is in terms of providing inputs to more powerful entities that operate up the value chain. To date, there is no evidence of formal firms cannibalising informal entities. The government e-waste formalisation empowers formal firms by enacting official laws on oversight and enhanced powers of enforcement but it fails to accommodate engagements with diverse informal economy players, some of whom are entirely preoccupied with their own survival. Government incisions into the e-waste space economy miss an understanding of the scale and scope of the informal sector. Evidently, a social understanding of how informal collection functions so efficiently and profitably is disregarded.

The envisaged piecemeal management framework is weak when addressing existing realities. A European-informed, top-down management approach with partial funding is being cut and pasted onto a very different economic and political environment. In Ghana, importantly, there is a lack of national political will and imagination to engage informal operators beyond a few place-based initiatives in Agbogbloshie. Several major barriers thwart informal economy participation including: prejudicial ingrained attitudes towards e-waste workers; virtually non-existent informals’ voice in policymaking; insufficient spending to realise a formal management transition; delays in passing the E-waste Management Act and its supporting apparatus for proper functioning (monitoring, data collection, updates on e-waste categories); scarcity of training for unskilled workers and green management; lack of investment in equipment, storage and other upgrades essential to transition informal infrastructure; lack of awareness among informal operators of business opportunities in formal e-waste, including no informal-formal mentorship programmes and low levels of awareness about informal e-waste activities and its management among policymakers and the general population (Chen et al. Citation2020; Oteng-Obabio et al. Citation2020).

In many ways, the imaginings for the future of e-waste in Ghana are not bold enough. A different and more important policy concern is how the informal economy can retain its employment-generating attributes while embracing green jobs/technology, increasing incomes, improving working conditions, using proper contracts, and being compliant with various regulations. Based on the country’s current level of socio-economic development, it remains highly unlikely that the entire value chain can transition towards formalisation. It also remains highly unlikely that the informal operators will disappear.

‘Gray space’ sheds different light on the intersections both longstanding and new between formal and informal entities. However, it should also be underscored that pure formality in which formal firms engage other formal firms is atypical in Ghana’s e-waste economy, and governmental and international donor desire for a single entirely formal, managed system may be misdirected. Indeed, it can also be argued that a pure informal sector exists only at the very base of e-waste, and when it comes to aggregation and metals trading many informal entities engage formal firms and various subcontractors. Therefore, the better way of conceptualising the formal/informal space is to frame the landscape as a continuum that is generated by a large grey zone which contains many shades of grey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amoyaw-Osei, Y, Opoku Agyekum, O, Pwamang, JA, Mueller, E & Fasko, R, 2011. Ghana e-waste country assessment. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). http://ewasteguide.info/files/Amoyaw-Osei_2011_GreenAd-Empa.pdf Assessed 8 January 2021.

- AMP (Agbogbloshie Makerspace Platform). 2017. Agbogbloshie makerspace platform. https://www.bfi.org/ideaindex/projects/2017/agbogbloshie-makerspace-platform-amp Accessed 15 July 2019.

- Atiemo, S, Faabeluon, L, Manhart, A, Nyaaba, L & Schleicher, T, 2016. Baseline assessment of e-waste management in Ghana. Ghana National Cleaner Production Centre, Sustainable recycling industries and Oko-Institute eV. Accra, Ghana.

- Baldé, CP, Wang, F, Kuehur, F & Huisman, J, 2014. Global e-waste monitor 2014: Quantities flows and resources. UNU, Bonn.

- Baldé, CP, Forti, V, Gray, V, Kuehr, R & Stegmann, P, 2017. Global e-waste monitor 2017. Quantities flows and resources. UNU, Bonn.

- Barrientos, S, Gereffi, G & Rossi, A, 2010. Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: Developing a framework for analysis. Working Paper 2010/3. https://globalvaluechains.org/sites/globalvaluechains.org/files/publications/ctg-wp-2010-3.pdf/ Accessed 18 August 2019.

- Chen, D, Faibil, D & Agyemang, M, 2020. Evaluating critical barriers and pathways to implementation of e-waste formalisation management systems in Ghana: A hybrid BWM and fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10360-8

- Chi, X, Streicher–Porte, M, Wang, M & Reuter, M, 2011. Informal electronic waste recycling: A sector review with special focus on China. Waste Management 31(4), 731–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.11.006

- Crang, M. & Cook, I, 2007. Doing ethnographies. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Crouch, M & McKenzie, H, 2006. The logic of small sample size in interview-based qualitative research. Social Science Information 45(4), 483–99.

- Daum, K, Stoler, J & Grant, R, 2017. Towards a more sustainable trajectory of e-waste policy: A decade of e-waste research in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14(2), 135–55.

- Dogbevi, E, 2016. Ghana to set up e-waste recycling plant. Ghana Business News, 17 Oct, p. 1. https://www.ghanabusinessnews.com/2016/10/17/ghana-to-set-up-e-waste-recycling-plant/ Accessed 15 July 2019.

- Doyon-Martin, J, 2015. Cybercrime in West Africa as a result of transboundary e-waste. Journal of Applied Security Research 10(2), 207–20.

- European Union (EU), 2018. E-waste management in Ghana: From cradle to grave. EU, Brussels.

- Fairphone, 2017. Collecting used phones from Africa to Europe. https://www.fairphone.com/en/2017/07/31/collecting-used-phones-from-africa-to-europe/ Accessed 15 July 2019.

- Government of Ghana, 2016. Ghana’s e-waste management bill 2016. http://greenadgh.com/images/documentsrepository/HazardousandElectronicWasteControl.pdf Accessed 15 July 2019.

- Grant, R, 2019. E-waste challenges in Cope Town: Opportunities for the green economy? Urban Izziv 30(2), 5–23.

- Grant, R & Oteng-Ababio, M, 2013. Mapping the invisible and real “African” economy: Urban e-waste circuity in Accra, Ghana. Urban Geography 33(1), 1–21.

- Grant, R & Oteng-Ababio, M, 2016. The global transformation of materials and the emergence of urban mining in Accra, Ghana. Africa Today 62(4), 2–20.

- Grant, R & Oteng-Ababio, M, 2019. Electronic waste circuitry and value creation in Accra, Ghana. In Scholvin, S, Black, A, Diez, J & Turok, I (Eds.), Value chains in Sub Saharan Africa: Challenges of integration into the global economy, pp. 115–32. Springer, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Greenpeace, 2008. Poisoning the poor – Electronics waste in Ghana. http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/news/features/poisoning-the-poor-electronil Accessed 15 July 2019.

- Holland Circular Hotspot, 2019. Market survey waste and circular economy in Ghana. https://hollandcircularhotspot.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Ghana-Market-Survey-Waste-Circular-Economy-100719.pdf Accessed 11 September 2019.

- Kumi, E, Hemkhaus, M & Bauer, T, 2019. Money dey for borla: An assessment of Ghana’s e-waste value chain. https://www.adelphi.de/en/system/files/mediathek/bilder/Value%20Chain%20Assessment%20Report_final_v3_1.pdf Accessed 4 September 2019.

- Le Moigne, R, 2017. Eliminating the concept of electronic waste. Circulate News. http://circulatenews.org/2017/07/eliminating-the-concept-of-electronic-waste/ Accessed 15 July 2019

- Lindell, I, & Ampaire, C, 2016. The untamed politics of urban informality: “Grey space” and struggles for recognition in an African city. Theoretical Inquiries 17, 257–82.

- Ngounou, B, 2020. Ghana: Switzerland invests €6.1 million for sustainable recycling of electronic waste. https://www.afrik21.africa/en/ghana-switzerland-invests-e6-1-million-for-sustainable-recycling-of-electronic-waste/ Accessed 26 April 2020

- Oteng-Ababio, M, 2010. E-waste: An emerging challenge to solid waste management in Ghana. International Development Planning Review 32(2), 191–206.

- Oteng-Ababio, M, Amankwaa, E & Chama, M, 2014. The local contours of scavenging for e-waste and high-valued constituent parts in Accra, Ghana. Habitat International 43(1), 163–71.

- Oteng-Ababio, M & Grant, R, 2019. Ideological traces in Ghana’s urban plans: How do traces get worked out in the Agbogbloshie informal settlement. Habitat International 83, 1–10.

- Oteng-Ababio, M, van der Velden, M & Taylor, M, 2020. Building policy coherence for sound waste electrical and electronic equipment management in a developing country. Journal of Environment & Development 29(3), 306–28.

- Prakash, S & Manhart, A, 2010. Socio-economic assessment and feasibility study on sustainable e-waste management in Ghana. Oko-Institute, V. Friedberg, Germany.

- Quaye, W, Akon-Yamga, G, Daniels, S, Ting, B & Asante, A, 2019. Transformation, innovation learning history of Ghana’s e-waste management system. http://www.tipconsortium.net/wp content/uploads/2019/10/Ghana_TILH_Oct2019_final.pdf Assessed 27 April 2020.

- Read, B, 2018. Serial interviews: When and why to talk to someone more than once. International Journal of Qualitative Methodology 17, 1–10.

- Stacey, P, 2019. State of slum: Precarity and informal governance at the margins in Accra. Zed, London.

- Sustainable Recycling Industries (SRI) & Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2018. https://www.sustainable-recycling.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/eWaste-Guidelines-Ghana_2018_EPA-SRI.pdf Accessed 3 September 2019.

- Wang, K, Qian, J & Liu, L, 2020. Understanding environmental pollution of informal e-waste clustering in Global South via multi-scalar regulatory frameworks: A case study of Guiyi Town, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, 1–18.

- Williams, C, 2019. The informal economy. Agenda Publishing, Newcastle.

- World Bank, 2015. E-waste technical report. http://greenadgh.com/images/documentsrepository/EwasteTechnicalReportWorldBank.pdf Accessed 15 July 2019.