?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Extant studies on the relationship between financial development and inequality have largely adopted single financial indicators especially the private credit/GDP. Unlike these works, the present study adopts a robust total financial development indicator based on four mainstays of financial development of financial deepening, efficiency, stability and access following the World Bank recommendation on the measurement of financial development. Using this measure, the paper examines the relationship in 40 African countries. The empirical results confirm the findings of extant studies that the ratio of private credit to GDP increases inequality in high, middle-low and low-income countries. The total financial development, however, reports mixed evidence. While this measure reduces inequality in high and middle-low income countries, it does not affect inequality in low-income countries. Also, the study finds evidence of a nonlinear relationship only among the low-income countries. The paper recommends that policymakers should formulate wholesome policies that cut across all mainstays of financial development to reduce inequality, particularly, in high and middle-low African countries. Also, policymakers are advised to increase growth in low-income countries so that financial development could reduce inequality. At most, these countries should pay less attention to financial development for inequality-reduction policies among low-income countries.

1. Introduction

The effect of financial development on macroeconomic policies is well documented in economic literature. Financial development influences economic growth, remittances, inflation, foreign direct investment and openness (Naceur & Zhang Citation2016; Rashid & Intartaglia Citation2017; Bolarinwa & Akinbobola Citation2021). Recently, the importance of financial development in addressing imperative development issues of poverty and income inequality has attracted the attention of scholars, governments, international organisations in developing countries and Africa continent in particular (Naceur & Zhang Citation2016; Zhang & Naceur Citation2018). This becomes more expedient because of the widespread inequality and poverty that ravages the continent which has resulted in low life expectancy, unemployment, corruption despite the high economic growth recorded recently. Following these incidences and the argument of Seer (1969), scholars and policymakers have therefore continued to devote more attention to development issues that affect the quality of life such as efficient and quality education, functional and accessible healthcare, infrastructural facilities, poverty reduction and low inequality in the continent.

Existing theoretical literature provides complex predictions on the relationship between financial development and inequality. Following Greenwood & Jovanovic (Citation1990), it is predicted that the relationship between financial development and economic development is bound to bring about a nonlinear U-shaped relationship between financial development and inequality. This theory documents that an increase in economic growth majorly resulting from financial development is expected to yield a high level of income inequality at the initial level of economic development. Over time, however, the economy stabilises, economic development occurs and the financial sector, in particular, becomes fully grown. This simultaneously improves economic growth and income of the poor. Therefore, there exists a non-linear relationship between financial development and inequality. Moreover, financial development reduces inequality in the long run. The theory, therefore, suggests that financial development allocates financial capital differently at several stages of economic development. However, the distributional impact of financial development is constrained by the level of economic development. This is because, at the initial level of development, only a few rich individuals could access and benefit from financial development. Contrarily, the works of Galor & Zeira (Citation1993) and Galor & Moav (Citation2004) argue that the relationship between financial development and inequality hinges on credit constraints. The theory suggests that financial development increases inequality in poor economies because of the high level of income inequality, on one hand. On the other hand, financial development is bound to reduce inequality in rich economies because of access to financial credit. As such, financial development is predicted to aggravates inequality in Africa since most of the countries are low-income economies and low-weak credit in the continent.

Indeed, the empirical literature has further compounded the issue of the relationship. This has yielded contradictory evidence. While some studies reported a negative relationship, implying that financial development reduces inequality (Beck et al. Citation2007; Bittencourt, Citation2007; Hamori & Hashiguchi Citation2012; Jauch & Watzka Citation2015; Naceur & Zhang Citation2016; Rashid & Intartaglia Citation2017; Rewilak Citation2017; Jung & Vijverberg Citation2019; Thornton & Di Tommaso Citation2019), some others have reported that the relationship between financial development and inequality is positive, hence, financial development increased inequality (Jaumotte et al. Citation2013; de Haan & Sturm Citation2017; Altunba & Thornton Citation2018; Casti Citation2018; Dabla-Norris et al. Citation2015). Still, few studies have reported both views on the relationship between financial development and income inequality (Bahmani-Oskooee & Zhang Citation2015; Zhang & Naceur Citation2018; Chiu & Lee Citation2019). Recently, studies have also reported a non-linear relationship (Kim & Lin Citation2011; Law et al. Citation2014; Chiu & Lee Citation2019).

One major issue among studies investigating the relationship is the narrow way in which financial development has been captured in extant studies. A large proportion of these papers adopted single financial development indicators of financial deepening such as the ratio of broad money supply (M2) to GDP (Claessens & Perotti Citation2007; Kunieda et al. Citation2011; Furceri & Loungani Citation2015); the ratio of bank credit to GDP (Aggarwal et al. Citation2011; Bettin & Zazzaro Citation2012; Ojapinwa & Bashorun Citation2014; Jauch & Watzka Citation2015; Karikari et al. Citation2016; Fromentin Citation2017; Rashid & Intartaglia Citation2017); bank deposit to GDP (Chowdhury Citation2016; Aggarwal et al. Citation2011; Bettin & Zazzaro Citation2012); broad money supply (M2) to GDP (Bettin & Zazzaro, Citation2012; Ojapinwa & Bashorun, Citation2014; Fromentin Citation2017) and the financial inclusion indicators (Anzoategui et al. Citation2014; Aga et al. Citation2014). In the context of Africa, few studies have investigated the relationship (Kapingura Citation2017; Tita & Aziakpono Citation2016).

This work argues that individual measures of financial development adopted by extant studies are not wholesome, adequate and sufficient for measuring total and robust financial development in developing countries and Africa in particular. First, financial deepening as captured by the ratio of private credit to GDP is not suitable for African countries because of the level of financial inclusion is low compared to other continents. Rather, this measure is suitable for advanced economies where there is a high level of financial inclusion, hence a large proportion of the population are financially included (See ). Besides, efficiency in the financial market which results from the high competition reduces the cost of funds, prices of financial products and encourages financial inclusion is a better measure of financial development considering the characteristics of African financial sectors. Also, financial access is a better measure of financial development is more suitable for capturing financial development in the continent considering the low level of financial inclusion in Africa.

Table 1. World Bank financial sector development pillars and indicators.

Moreover, stability is equally expedient for measuring financial development considering the impact of the financial crisis in major economies and their spillover effect on African economies. Thus, a wholesome indicator that accommodates these individual measures are more likely to capture financial development more adequately in the context of African countries. This measure could also help better analyses the relationship between financial development and inequality since indicators of access, stability, and efficiency seems much more relevant than financial deepening for measuring financial development in the context of Africa. Besides, these four indicators of financial access, stability, efficiency and deepening simultaneously occur in an economy. Hence, the exclusion of any of these indicators implies that the measure of financial development might not be adequate, robust and wholesome. Against this background, this study adopts a wholesome measure of financial development based on a composite measure of financial development that accommodates the four mainstays of financial development-depth, efficiency, stability, and access following the World Bank measure and classifications of financial development and few studies in the literature (Altunbas & Thornton Citation2018; Bolarinwa & Akinbobola Citation2021; Thornton & Tommaso Citation2019). Using this indicator, this paper reports empirical evidence from African continent considering the low level of financial development and high inequality in the continent (see and ).

The paper contributes to the literature on three major grounds. First, following few studies in the literature, the paper adopts a robust financial development measure using the four pillars of financial deepening, stability, access and efficiency as advocated by the World Bank (see ; Cihak et al. Citation2013). This measure yields a more robust financial development indicator based on principal component analysis (PCA) methodology. Second, this paper documents evidence on the relationship from African continent using income groupings in the continent as our yardstick. To the best of our knowledge, no study has undertaken this. This allows us to examine whether the same relationship holds for all income groups. We focus on the African continent because of high inequality and the low level of financial development in the continent (See ). Third, this paper investigates the nonlinear relationship in the context of African countries following the theoretical propositions of Greenwood & Jovanovic (Citation1990) and few empirical studies in developed and other developing countries. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The second section addresses the trends of financial development and inequality in the selected countries while the third section critically examines methodology adopted in the paper. The fourth section equally presents empirical results and interpretations. Lastly, section five provides a brief conclusion and recommendations.

Table 2. Data and sources.

2. Trend of financial development and inequality across the world

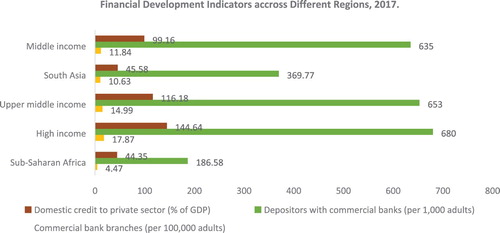

and present the trends of inequality and financial development across different regions of the world. Using financial development indicators of the ratio of credit to the private sector to GDP, the number of depositors with commercial banks per 1000 adults and the commercial branches per 100,000 adults in 2017, shows that high-income countries have the highest performance in all indicators compared to all other income groupings. The study further reports indicators from sub-Saharan Africa and other less developed regions in terms of financial development globally. We equally find out that African continent performs poorly in terms of all financial development indicators. This shows the imperative of investigating the relationship in African continent separately. Regarding the inequality pattern across the world, the study compares the level of inequality in Africa with the best economies in Europe and the US. As shown in , Nigeria has the highest level of inequality among the six selected African countries. Surprisingly, South Africa follows. The least developed country in Africa is Benin republic. Among the developed economies, the USA has the highest level of inequality among the selected countries while Norway and Sweden have the least inequality among the selected developed countries.

3. Methodology

3.1. Empirical model

Following extant studies, the empirical model on the relationship between poverty and income inequality estimated in the study is specified as follows:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2) Where FD and INQ are financial development and income inequality respectively while X is the matrix of control variables of trade openness, economic growth, government spending, institutional quality, and educational achievement.

is a time-specific effect captured by a set of time-dummy variables while

is the composite error term comprising of unobserved country-specific and

is the observation-specific error in the model. While inherent endogeneity has been reported in the interaction between financial development and inequality due to country-specific heterogeneity and persistence of inequality (Beck et al. Citation2004; Calderón & Servén Citation2004; Batuo et al. Citation2010), most recent studies have neglected this problem (Zhang & Naceur Citation2018; Chiu & Lee Citation2019; Jung & Vijverberg Citation2019). To address this issue, this study adopts the two-step system GMM of Blundell & Bond (Citation1998) to estimates the model. To capture the inherent endogeneity, one lag of the dependent variable is adopted in the model. Our control variables are not chosen arbitrarily. Trade openness is adopted because it is believed that trade openness reduces poverty and consequently, inequality following extant literature (Faustino & Vali Citation2011; Georgantopoulos & Tsamis Citation2011; Mitra & Hossain Citation2018). According to Hecksher-Ohlin-Samuelson trade theory, trade openness increases the real and nominal returns of abundant unskilled labour in developing economies as these economies specialise in and export unskilled labour products. This, therefore, decreases the gap between the skilled and unskilled labour which forms the majority of the poor. Besides, economic growth is a significant factor for explaining inequality because of its redistribution effects. We equally include its lag into the model to capture the existing distribution pattern. Also, government spending equally aims at redistribution of income hence it reduces inequality. Furthermore, it is argued that the level of inequality in an economy largely depends on the quality of institution. Last, educational attainment is a strong weapon assumed to reduce income inequality.

3.2. Data and sources

The paper adopts an unbalanced panel covering the period between 1999 and 2015 for 40 African countries. The study is constrained by data unavailability for financial development indicators of access, stability, and efficiency, hence, the selection of the sample period. These countries are divided into three income levels of high-income, middle-low income and low-income countries following World Bank division. This is with the view of examining whether the relationship changes as income increases. A display of these countries based on the World Bank income level groupings is shown in . Following Arestis & Caner (Citation2010) and Rashid & Intartaglia (Citation2017), we take the 4-year average to address short-run disturbances of the business cycle and to maximise country observations. Thus, our panel estimation comprises of four periods. Only countries with at least three-year observation are included in the modelling. All data asides from inequality measure are sourced from World Bank Development database managed by World Bank (Citation2019). Our inequality data are sourced from the Solt’s (Citation2009) Standardised World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) 2018 version. This GINI coefficient is based on household income before taxes. This method has been used by some studies (Altunbas & Thornton Citation2018; Thornton & Di Tommaso Citation2019). To measure financial development, we adopt the PCA of total financial development developed by the World Bank and the IMF. This measure covers the depth, breadth, efficiency, and access to financial institutions and financial market (Svirydzenka Citation2016; Bolarinwa & Akinbobola Citation2021; Thornton & Di Tommaso Citation2019). provides further information on these variables, sources, and proxies.

Table 3. Countries adopted in the study according to income grouping.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of the variables (High-Income Countries).

4. Empirical results and discussions

4.1. Descriptive statistics

This paper begins the empirical analysis by examining the descriptive statistics because this provides a synopsis of the empirical results. show that inequality varies greatly among income levels in Africa. For instance, inequality ranges between 41% and 68% in High-income countries, the same ranges between 31%–60% and 29.5%–60% for middle-low and low-income countries respectively. Average of 64%, 49%, and 44.5% are recorded for high income, middle-low income, and low-income countries respectively. These results show that inequality increases with income levels. High-income countries record high inequalities than the least developed economies in Africa. The financial development indicators among these countries also show some variations. Among high-income countries, an average of 45% private credit is recorded. The same variable is 17.6% and 13% in middle-low and low-income countries respectively. This is within the minimum and maximum values of 2%–160%, 2%–65.7% and 0.5%–103% for high, middle-income and low-income countries respectively. For the degree of competition measure of financial development, high-income countries record the highest degree of competition, this is followed by middle-low income and low-income countries respectively. Thus, it could be deduced that the income level may be positively related to the degree of competition. No wonder, financial sectors in these economies are more developed than others in the continent. The same performance is equally shown in the stability indicator of Z-Score. The high-income countries also have the highest level of stability than the low-income and low-income countries. In terms of account ownership, this study adopts the numbers of account ownership of the adult population in the formal financial institutions. Like other financial development indicators, the high-income countries have the highest score with the maximum and minimum values of 2019–10 per 1000 people. For the low-middle and low-income countries, we have 1860–0.4 and 4.9–0.7 respectively per 1000 individuals. Lastly, we examine the GDP per capita among the groupings. For high-income countries, there is an average of $7978 while an approximate of $1667 and $504 is reported in middle-income and low-income countries respectively. Overall, there are wide differences in income among the groupings. Besides, inequality increases as per capita income grow in the continent.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of the variables (Middle-Low Income Countries).

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of the variables (Low-Income Countries).

4.2. Analysis of unit root and correlation

To determine the appropriate method, this paper equally examines the unit root properties of the variables in the study. To determine this, we adopt five renown tests in the empirical literature. They are Levin, Lin & Chu, LLC, (2002); Breitung (2002); Im, Pesaran & Shin, IPS, (2003); Augmented Dickey–Fuller, ADF-Fisher (2004) and the Phillips–Perron-Fisher chi-square, PP-Fisher, (1999). While both LLC and Breitung assume common unit root processes among cross-sectional units, the rest assume individual unit root processes across cross-sections. The empirical results are shown in . The Table shows that four variables of Inflation, Income, Trade openness, and government expenditure are stationary at levels while three variables of Inequality, School Enrolment, and Institutional Quality are stationary at first difference. Hence, the variables are a mixture of I(0) and I(1). Similarly, our total financial development indicator, the overall indicator which captures all the four measures of financial indicators, is stationary at first difference. A major implication arising from the empirical results is that the ordinary fixed/random effects models popular in the literature might not be appropriate, thus the present Generalised Method of Moment (GMM) is more appropriate for examining the relationship between inequality and financial development. We equally examine the correlation between the variables adopted in the model. The results are shown in . The Table shows a positive relationship between inequality and financial development, this implies that financial development tends to worsen inequality. However, to validate this result, there is a need to examine the econometric results on the relationship. Besides, the results are largely close to 50% for most of the variables while few are above 50%. However, there is no need for concern for multicollinearity of autocorrelation in the model since the SGMM technique is adequate for addressing these issues.

Table 7. Result of the panel unit root test (Individual Effects and Trends).

Table 8. Correlation matrix.

4.3. Analysis of the principal component analysis (PCA) model of the total financial development indicator

The paper equally examines the composition of the PCA model of total financial development, which captures all four financial indicators, using the correlation method. The result is available on request.

More importantly, documents empirical results from our baseline model which comprises all 40 countries adopted in our sample. We further split this sample into three-high income, lower-middle-income, and low-income countries following World Bank income grouping. Having estimated the sample of low-income countries with the 20 countries, the individual models for high-income comprising 7 and 13 countries in low-middle income could not be estimated in Stata probably due to smallness of the sample, hence, the study merged both samples thus we have a new sample for both low-middle and high-income countries. and present their results respectively. For , the probability values for Sargan test of over-identification are significantly higher than the required 5%, thus the null hypothesis cannot be rejected in all specifications thus the estimates are orthogonal to residuals. This shows that the instruments adopt in all specifications are not over-identified. The implication is that all instruments are valid and appropriate, hence, our coefficients are robust and reliable for predictions and policy recommendations. We further examine the autocorrelation using Arellano & Bond first and second-order autocorrelation tests. Our results equally show that all specifications do not suffer from autocorrelation. Judging by the probability values, the estimates are greater than the required 5%, hence, the null hypothesis that the residuals are not serially correlated are accepted. Hence, our estimates are robust, appropriate and reliable for policy formulations.

Table 9. Effect of financial development on inequality in Africa (All African Countries).

Table 10. Effect of financial development on inequality in Africa (Low-Income Countries).

Table 11. Effect of financial development on inequality in Africa (High & Middle-Low Income Countries).

Our empirical results on the relationship are particularly interesting. We discover that our empirical results are not only in agreement with existing studies and a priori expectation but also provides new insights into the relationship between financial development and inequality in the context of Africa. For the baseline model, the dynamism of the model captured by the one-period lag of inequality is positive and statistically significant at 1% in all specifications. This supports the recent argument on the existence of endogeneity and reverse causation in the relationship (Batuo et al. Citation2018; Zhang & Naceur Citation2018). It equally implies that financial development persists over time, hence, the popular static models in the literature might be inappropriate. Thus, the superiority and appropriateness of the GMM method are validated by our findings. The empirical results also validate the importance of financial development indicator of private credit in addressing inequality. However, the empirical results show a significant positive relationship. This implies that financial development increases inequality in Africa. Our result is in line with extant literature in both developed and developing countries on the subject (Claessens & Perotti Citation2007; Jauch & Watzka Citation2015; De Haan & Sturm Citation2017; Altunbas & Thornton Citation2018; Chiu & Lee Citation2019). Possible explanations for these results are that the financial sector provides a disproportionately larger share of financing in African economy to only high-income groups, thus supporting the theoretical proposition of Galor & Zeira (Citation1993) and Galor & Moav (Citation2004) which stipulates that credit constraints trigger financial development to increase inequality. This is because only a few high-income groups could access the benefits of financial development. However, the finding on the relationship between inequality and account ownership per 1000 people contradicts the works of Zhang & Naceur (Citation2018). The result validates the is real in the context of Africa because only a few proportions of the populace could access financial benefits provided by the financial sector of these economies as shown in the trend of inequality earlier.

Besides, the role of other financial mainstays of stability, efficiency, and access are not validated in the study. For the wholesome measure of financial development, this does not have any effect on inequality. This implies that only the popular narrow view of private credit is important for estimating the relationship in the context of African countries, thus overall financial development indicator does not affect inequality in Africa. Also, the paper does not validate the nonlinear relationship in the baseline model, thus, the position of the theory on the nonlinear relationship is not justified by our findings on the overall model that capture all countries. This contradicts the findings of Kim & Lin (Citation2011); Brei et al. (Citation2018) on developed and developing countries. Concerning the control variables, inflation, a measure of macroeconomic instability is positive and statistically significant in all specifications. This implies that inflation increases inequality generally in the continent. However, the absolute effect of the variable is negligible in all specifications. More importantly, the role of income is highly important in tackling inequality in Africa. This view is validated in five out of the six models. The empirical results imply that inequality decreases with an increase in per capita income in the baseline results. This is in line with the submissions of the pro-poor effect of growth and agrees with extant empirical literature (Dollar & Kraay Citation2002; Kraay Citation2006). The lag of income indicating the existing pattern of income distribution and trade openness are equally significant for addressing inequality. While trade openness reduces inequality, the existing pattern of income distribution increases inequality in Africa.

4.3.1. Effect of financial development on inequality in low-income countries

This paper also investigates the relationship between income levels. shows the empirical results for low-income countries. Like the baseline model, the dynamic nature of the relationship is further validated in all specifications at 1% significant level. Similarly, both post-estimation tests of Sargan and AB autocorrelation tests are satisfied in all specifications. Inequality-enhancing role of financial development using private credit as an indicator is validated in low-income countries. Similarly, account ownership reduces inequality in low-income countries. This agrees with the a priori expectation and therefore implies that account ownership has enabled poorer households the opportunity for consumptions smoothing and personal loans. Hence, the reduction of inequality reduces poverty among low-income countries. Thus, the present policy of financial inclusion strategy, emanating from financial access, among African countries particularly the low-income countries tends to reduce inequality. This is in line with the findings of Zhang & Naceur (Citation2018). However, like the baseline model, a robust total financial development indicator, which captures the four pillars of financial indicators of stability, access, deepening and efficiency does not have a significant effect on inequality in low-income countries as earlier established in the baseline model. The intuition from the results is that the financial development indicators of Z-Score, Boone, Private credit and account ownership are highly important for addressing inequality in the middle- and high-income counties. Thus, these measures of financial development measures are only in the middle- and high-income countries. The result is plausible because the measures of financial development adopted in the study are highly associated with the commercial banking system which is far from the poor. Hence, the insignificance of the total financial development indicator is not surprising in low-income countries.

Moreover, the submission of the nonlinear effect in the relationship following the work of Greenwood & Jovanovic (Citation1990) is equally validated in the low-income countries model, unlike the baseline model. Regarding the control variables, inflation rate existing income distributional pattern and trade openness all have a significant effect on inequality thus confirming baseline the findings of the baseline model. However, income has a negative impact thus increasing the level of inequality in low-income countries. This is in contrast with the submission of the pro-poor growth theory. Hence, as income grows in these economies, inequality increases. This is plausible for some reasons. One, as validated by the lag of income, an indicator of existing income distributional pattern, as income increases among these countries, the rich get richer while the poor get poorer. Hence, inequality widens. Besides, only a few rich among the low-income countries could access the gains and benefits of financial development as provided by the private credit which is significant in the model. This privileged few thus benefits maximally from the gains of financial development in the economy at the expense of a large proportion of the populace. Thus, the view that ‘90% of GDP of low-income countries in Africa are in the hands of 10% of the population’ is verified by our empirical findings. One reason for this is the level of corruption which permits leaders to embezzle public funds for private gains in these economies. Lastly, education is a strong weapon for reducing inequality in low-income countries. This is because education creates an opportunity for employment which tends to reduce inequality.

4.3.2. Effect of financial development on inequality in high and middle-low-income countries

Last, this paper documents empirical results from the high-income and middle-low income countries. Like other specifications, the post-estimation tests and the dynamic nature of the models are validated in the results. However, the specification provides some different results unlike existing findings from the baseline and low-income groupings. First, this speciation validates the view that financial development reduces inequality. Second, financial development indicator of stability which is captured by Z-Score equally reduces inequality among these countries. However, private credit still reduces inequality. The reasons for these different results are not farfetched. One, these grouping accommodates the most developed financial sectors in Africa including South Africa. This implies that these economies have benefitted from financial development, unlike average African country. This is evidenced in the account ownership, Boone indicator, private credit, and Z-Score indicators. Hence, a robust financial development indicator could further have an impact on these economies. Second, it could be concluded from these facts that a large proportion of the population in these countries have been able to access financial services and its benefits, unlike low-income countries. Hence, the impacts of the total financial development indicator. For the control variables, the negative role of income for reducing inequality is established among high-income countries, unlike the low-income countries. This contradictory result is justified considering established distributional pattern among high-income countries, unlike the low-income countries where this is not existing. However, government expenditure increases inequality. This is explainable considering the weak quality of institutions in Africa generally. high-income countries. School enrolment, however, reports contradictory results. This shows that education increases inequality among these countries. This is justified by the level of unemployment of graduates generally among African countries. Last, inflation increases inequality as reported in other specifications.

5. Conclusions and policy recommendations

This paper investigates the relationship between financial development and inequality among selected 40 countries in Sub-saharan Africa. Motivated by the widespread inequality and low financial development in the continent, the paper further segregates these countries into high, middle-income and low-incomes countries. Following the view that there exists an endogeneity in the relationship, the paper adopts a dynamic panel method of system generalised method of moment (SGMM) for estimating the relationship. Unlike other studies in the literature, this work adopts income levels to examine the relationship among African countries. Similarly, the work uses a robust measure of financial development built using PCA techniques. The empirical results confirm the findings of extant studies that the ratio of private credit to GDP increases inequality in all income levels. The total financial development, however, reports mixed evidence. While this measure reduces inequality in high and middle-low-income countries, it does not affect inequality in low-income countries and the overall model comprising all countries. Also, the study finds evidence of a nonlinear relationship only among the low-income countries.

Two major implication arises from this study. One, financial development using a single indicator of the ratio of private credit to GDP increases inequality in Africa. Hence, policymakers are advised to pay little attention to this measure for measuring financial development in the context of Africa. Rather, policy formulations should be based on robust financial development that comprises all four indicators for addressing issues in Africa. Second, robust financial development indicator equally reduces inequality in middle-income and high-income countries in Africa and not in low-income countries. As the indicator of robust financial development is only significant in the middle- and high-income countries, it implies that these countries have attained the threshold level of financial development necessary for financial development for impacting poverty and consequently inequality levels in these economies. It also implies that some levels of economic development are necessary for financial development to have a considerate effect for reducing inequality. Moreover, the results suggest that indicators of robust financial development measure are more effective in addressing inequality in these economies. It is therefore suggested that government in low-income countries should pay utmost attention to growth levels for financial development to have its impacts on inequality reduction policies in these economies. More importantly, this paper agrees with the World bank submission of using robust and total financial development indicator that addresses access, efficiency, stability and financial deepening for addressing issues in the financial sector in Africa. This is because these indicators are particularly important for Africa considering the low level of financial inclusion in the continent. The paper, therefore, recommends that policymakers should formulate wholesome policies that cut across all mainstays of financial development for reducing inequality, particularly, in high and middle-low African countries. Also, less attention should be focused on financial development for inequality-reduction policies among low-income countries. Moreover, this present study adopts only accounts per 1000 people for measuring financial access. While this is a weak measure, the study is constrained by data on other measures such as mobile banking, borrowing etc., hence, its use.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aga, GA, Peria, M & Soledad, M, 2014. International remittances and financial inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa. Policy Research Working Paper; No. 6991. World Bank Group, Washington, DC.

- Aggarwal, R, Demirguc-Kunt, A & Peria, MSM, 2011. Do remittances promote financial development. Journal of Development Economics 96(2), 255–64.

- Altunbas, Y & Thornton, J, 2018. The impact of financial development on income inequality: A quantile regression approach. Economics Letters. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2018.12.030

- Anzoategui, D, Demirgüç-Kunt, A & Pería, MSM, 2014. Remittances and financial inclusion: Evidence from El Salvador. World Development 54(1), 338–42.

- Arestis, P & Caner, A, 2010. Capital account liberalization and poverty: How close is the link? Cambridge Journal of Economics 34(2), 295–323.

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M & Zhang, R, 2015. On the impact of financial development on income distribution: Time-series evidence. Applied Economics 47, 1248–71.

- Batuo, ME, Guidi, F & Mlambo, K, 2010. Financial development and income inequality: Evidence from African countries.

- Batuo, ME, Guidi, F & Mlambo, K, 2018. Financial development and income inequality: Evidence from African countries.

- Beck, THL, Demirgüç-Kunt, A & Levine, R, 2004. Finance, inequality and poverty: Cross-country evidence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 3338. The World Bank, Washington DC.

- Beck, T, Demirgüç-Kunt, A & Levine, R, 2007. Finance, inequality and the poor. Journal of Economic Growth 12, 27–49.

- Bettin, G & Zazzaro, A, 2012. Remittances and financial development: Substitutes or complements in economic growth? Bulletin of Economic Research 64(4), 110–23.

- Bittencourt, M, 2007. Financial development and inequality: Brazil 1985–1994. Discussion papers//Ibero America Institute for Economic Research, No. 164. Ibero-Amerika-Inst. für Wirtschaftsforschung, Göttingen.

- Blundell, R & Bond, S, 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87(1), 115–43.

- Bolarinwa, ST & Akinbobola, TO, 2021. Remittances-financial development nexus: Causal evidence from four African countries. Ilorin Journal of Economic Policy 8(1), 1–17.

- Brei, M, Ferri, G & Gambacorta, L, 2018. Financial structure and income inequality. BIS Working Paper No. 756.

- Calderón, C & Servén, L, 2004. The effects of infrastructure development on growth and income distribution. Policy Research Working Paper; No.3400. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Casti, C, 2018. Income inequality and financial development: A multidimensional approach. Paper prepared for the 35th IARIW General Conference Copenhagen, August 20–25, 2018, Denmark, Session 7E-1, Short Paper Session: Financial Accounts Time: Friday, August 24, 2018 [14:00-17:30].

- Chiu, Y-B & Lee, C-C, 2019. Financial development, income inequality, and country risk. Journal of International Money and Finance. doi:10.1016/j.jimonfin.2019.01.001

- Chowdhury, F, 2016. Financial development, remittances and economic growth: evidence using a dynamic panel estimation. Margin The Journal of Applied Economic Research 10(1), 35–54.

- Cihak, M, Demirgüc-Kunt, A, Feyen, E & Levine, R, 2013. Financial development in 205 economies, 1960 to 2010. Journal of Financial Perspectives 1, 17–36.

- Claessens, S & Perotti, E, 2007. Finance and inequality: Channels and evidence. Journal of Comparative Economics 35(4), 748–73.

- Dabla-Norris, E, Kochhar, K, Ricka, F, Suphaphiphat, N & Tsounta, E, 2015. Causes and consequences of income inequality: A global perspective. IMF Strategy, Policy, and Review Department Staff Discussion SDN/15/13.

- De Haan, J & Sturm, J-E, 2017. Finance and income inequality: A review and new evidence. European Journal of Political Economy 50, 171–95.

- Dollar, D & Kraay, A, 2002. Growth is good for the poor. Journal of Economic Growth 7(3), 195–225.

- Faustino, H & Vali, C, 2011. The effects of globalization on OECD income inequality: A static and dynamic analysis. Working Papers Department of Economics 2011/12. ISEG-Lisbon School of Economics and Management.

- Fromentin, V, 2017. The long-run and short-run impacts of remittances on financial development in developing countries. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 66(C), 192–201.

- Furceri, D & Loungani, P, 2015. Capital account liberalization and inequality. IMF Working Paper No WP/15/243.

- Galor, O & Moav, O, 2004. From physical to human capital accumulation: inequality and the process of development. The Review of Economic Studies 71(4), 1001–26.

- Galor, O & Zeira, J, 1993. Income distribution and macroeconomics. The Review of Economic Studies 60, 35–52.

- Georgantopoulos, GA & Tsamis, DA, 2011. The impact of globalization on income distribution: The case of Hungary. Research Journal of International Studies 21(1), 17–25.

- Greenwood, J & Jovanovic, B, 1990. Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy 98, 1076–107.

- Hamori, S & Hashiguchi, Y, 2012. The effect of financial deepening on inequality: Some international evidence. Journal of Asian Economics 23(4), 353–9.

- Jauch, S & Watzka, S, 2015. Financial development and income inequality: A panel data approach. Empirical Economics. doi:10.1007/s00181-015-1008-x

- Jaumotte, F, Lall, S & Papageorgiou, C, 2013. Rising income inequality: Technology, or trade and financial globalization? IMF Economic Review 61(2), 309–21.

- Jung, SM & Vijverberg, CC, 2019. Financial development and income inequality in China – A spatial data analysis. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 48(C), 295–320.

- Kapingura, FM, 2017. Financial sector development and income inequality in South Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 8(4), 420–32.

- Karikari, NK, Mensah, S & Harvey, SK, 2016. Do remittances promote financial development in Africa? SpringerPlus 5(1), 1011–21.

- Kim, D & Lin, S, 2011. Nonlinearity in the financial development-income inequality nexus. Journal of Comparative Economics 39, 310–325.

- Kraay, A, 2006. When is growth pro-poor? Evidence from a panel of countries. Journal of Development Economics 80(1), 198–227.

- Kunieda, T, Okada, K & Shibata, A, 2011. Finance and inequality: How does globalization change their relationship? Macroeconomic Dynamics 18(5), 1–13.

- Law, SH, Tan, H & Azman-Saini, WNW, 2014. Financial development and income inequality at different levels of institutional quality. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 50(s1), 21–33.

- Mitra, R & Hossain, S, 2018. Does trade openness increase income inequality in the United States? The Empirical Economics Letters 17(10), 1185–94.

- Naceur, SB & Zhang, R, 2016. Financial development, inequality and poverty: Some international evidence. IMF Working Paper 16/32.

- Ojapinwa, TV & Bashorun, OT, 2014. Do workers’ remittances promote financial development in sub-Sahara Africa countries? International Journal of Financial Research 5(2), 151–9.

- Rashid, A & Intartaglia, M, 2017. Financial development – Does it lessen poverty? Journal of Economic Studies 44(1), 69–86.

- Rewilak, J, 2017. The role of financial development in poverty reduction. Review of Development Finance 7(2017), 169–76.

- Solt, F, 2009. Standardizing the world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly 90, 231–242.

- Svirydzenka, K, 2016. Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. Working Paper No. 16/5.

- Thornton, J, & Di Tommaso, C, 2019. The long-run relationship between finance and income inequality: Evidence from panel data. Finance Research Letters. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2019.04.036

- Tita, AF & Aziakpono, MJ, 2016. Financial development and income inequality in Africa: A panel heterogeneous approach. Working Papers 614, Economic Research Southern Africa.

- World Bank, 2019. World Development Indicators. Online.

- Zhang, R & Naceur, SB, 2018. Financial development, inequality, and poverty: Some international evidence. International Review of Economics and Finance. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2018.12.015