?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The corporate income tax (CIT) systems of developing countries can potentially be contributors or impediments to their economic development. This is especially relevant in the SADC region that has a set agenda regarding regional integration goals, and where the guiding principle is tax harmonisation that benefits all members through tax reform efforts. Despite the importance of the topic, empirical literature remains scant, and this paper attempted to revisit the CIT determinants in the SADC region. Having a larger database at their disposal, the authors could update the existing empirical literature. The sample period of the study included the commodity booms and slumps following the global financial crises, and illustrated the varying fortunes of developing countries in general, and the SADC specifically. Furthermore, given the lower economic growth, together with the variable commodity prices since 2008, there is a concern that corporate tax revenue may continue to erode. A cross-section panel was utilised to determine those factors that may best explain changes in corporate taxes in Southern Africa over the period of time from 1980 to 2017.

1. Introduction

Corporate income tax (CIT) systems have the potential to contribute to or impede the economic development of developing countries, and as such, present a particularly difficult dilemma. For example, the IMF (Citation2014) found that developing countries are up to three times more vulnerable to the negative effects of other countries’ tax rules and practices than developed nations are.

In this regard, Robinson (Citation2006) argued that in developing countries public needs should take precedence over tax policies that generate uncertain revenue. This gives rise to the question whether it is the internal public needs, in the shape of a coordinated effort that determines CIT, or whether external competitive pressures determine CIT tax rates in developing countries. Empirical evidence on this remains scant. Most existing studies focus on trends in corporate tax rates and changes in tax bases, such as the work of Keen & Simone (Citation2004), Keen & Mansour (Citation2010) and Abbas et al. (Citation2012). In the context of the SADC, a few recent studies have been published on tax coordination in the region, however, these studies tend to focus on indirect taxes, such as VAT (value added tax) (see Letete, Citation2012). Robinson’s (Citation2006) study remains the only study focusing on the determinants of CIT in the SADC region.

In an attempt to identify these alternative factors affecting CIT rates, one needs to explore the hypothesis whether internal or local pressure for public goods delivery determines the CIT rates in the SADC region. If this problem statement holds true, it is accepted that internal (local) pressure takes precedence in the determination of CIT rates. Internal needs for public goods delivery then becomes a priority, together with the varied consequences (Robinson, Citation2006).

2. Background

The 16 SADC member states have a population of over 200 million with an expanding consumer class. As many SADC economies are too small to draw significant investment on their own, regional integration and cooperation are at the centre of the organisation as a means of creating a more attractive environment for foreign investment. Tax coordination and harmonisation are regarded as basic requirements for economic integration. It is against this background that the SADC’s Memorandum of Understanding on Co-operation in Taxation and Related Matters, and the SADC Protocol on Finance and Investment have been developed as tools to achieve the coordination and harmonisation of taxation laws within the region and to avoid harmful tax competition among the member states through tax incentives (IMF, Citation2015).

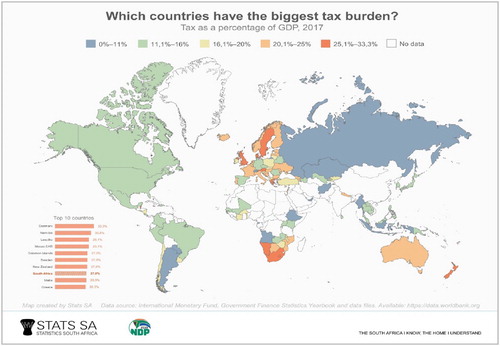

The structure of many developing economies is characterised by many small producers that operate outside the formal sector or that are officially exempt due to their size, and this could lead to revenue authorities being highly dependent on a few large businesses. In terms of the tax revenue-to-GDP ratio, the DRC stands at less than 13%, while the ratios in Angola, Zambia, Malawi and Tanzania are between 13 and 18%, with the remainder of the SADC members at above 18%. For some countries, the tax revenue-to-GDP target is still below the minimum level of 20%, which the UN considers necessary for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. South Africa (27%) finds itself ahead of other countries, such as Australia (22,2%), Brazil (12,7%) and the United States (11,9%). The world average, according to the IMF, was 15.4% in 2017. It should be kept in mind that social security contributions are not included, and that child, disability and old age grants or universal credits are excluded.

Whether a high GDP-to-tax ratio is a good or a bad thing is dependent upon each country’s view. For a nation that has a high ratio, but where taxpayers receive good value for money, a high tax burden might not be that detrimental. For example, Denmark, Sweden and Norway have high tax-to-GDP ratios, but these nations also report the highest standard of living.

A very low tax-to-GDP ratio can be problematic as it may be a sign of an inefficient tax system. A government will struggle to provide services, build infrastructure or maintain public goods if it fails to collect taxes during periods of strong economic growth. The tax-to-GDP ratio alone provides no indication of good governance, nor of the efficiency of the taxation system in the country, or the way in which taxes are used or distributed.

However, the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) countries are in close proximity to South African and rely on South Africa for revenue. For example, South Africa’s neighbouring countries Lesotho’s and Namibia have tax-to-GDP ratios of 29.1% at 30.8%, respectively. In developed countries, such as Denmark and the United Kingdom, this ratio was 33% (StatsSA, Citation2019). Base broadening is thus still an objective for less developed regions such as southern Africa, where economic growth is still low, together with a resultant high unemployment rate. ().

This is particularly alarming in the context of the literature that shows that a lack of a certain level of harmonisation of the national tax systems and a lack of harmonised tax policy could compromise SADC integration as a whole (IMF, Citation2015:30).

3. Literature review

3.1. The origin of tax competition literature

Tax competition is presented in the academic literature as a game between two or more countries that make choices simultaneously and non-cooperatively in terms of their tax policy, usually their tax rate, on an internationally mobile tax base, usually capital. In simple terms, tax competition includes the welfare effect of one country’s tax policy when goods and/or factors of production are traded internationally. It therefore deals with various measures or strategies that can be taken by governments on the same or horizontal level, but also different or vertical levels, to adjust their tax rates or reconsider their tax systems (especially tax bases), in order to attract mobile factors of production from other regions. Tax competition therefore does not only occur through the lowering of tax rates, but also from changes or distortions in tax bases that are less visible and more difficult to assess. Mobile tax bases include income from sales and services (commodities), income and assets from labour, income from rentals and royalties, income from portfolio capital (interest income), and income from corporate profits or investment capital.

Since capital is far more mobile than other production factors, research on tax competition focuses on the taxation of capital income. That is, where the elasticity for the supply of capital is relatively high, making reduction of the cost of having capital, such as CITs, an attractive opportunity for governments to attract capital. This mobility induces some international spill-overs in the design of national tax policy. Interdependencies (fiscal externalities) trigger a ‘race to the bottom’, as each country tries to attract a disproportionate share of the mobile capital tax base. In equilibrium, tax rates are lower in both countries than they would otherwise be, resulting in lower tax revenues and/or a shift of the tax burden to immobile tax bases.

Nearly all the models considered above predict that capital mobility decreases the source-based tax on the mobile factor (capital) and shifts the tax burden towards immobile factors (labour). Capital mobility also decreases tax revenues and the provision of public goods, thereby undermining the fairness and social acceptance of tax. There are, however, counteracting or mitigating factors, such as the size of the country, agglomeration benefits, foreign ownership and political pressure. The strength of each of these factors is largely an empirical issue.

Tax competition literature can be extended to include various other theories. In an open economy, governments often cannot fully tax foreign destined income due to capital flight (tax evasion) or the manipulation of transfer prices within multinational corporations. Governments are not always inclined to report to foreign fiscal authorities on, for instance, income from those residents investing abroad. However, double taxation agreements and exchange of information have occurred internationally. Empirical evidence has been provided in terms of tax enforcement problems (tax evasion), and thus the survival of capital income taxes (Gordon, 1992).

Based on models such as that of Zodrow & Mieszkowski (Citation1986), a small body of literature started to emerge that attempted to provide insight into how countries determine their corporate tax rates. The variables employed in these types of studies include country-specific determinants. According to public finance literature, an understanding of tax systems requires an understanding also of external pressures such as the effect of economic integration within a region (Devereux et al., Citation2005; Devereux et al., Citation2008).

Country-specific determinants of corporate tax rates are especially relevant in the developing country context.

The advantage of size reduces fiscal stress in small countries because it broadens the revenue base: directly through capital inflows and higher revenues from capital taxation, and indirectly, because the capital inflows push up the capital–labour ratio (i.e. labour becomes relatively scarcer which increases its worth), and it thus fuels revenue from labour and consumption taxation.

4. Empirical evidence

A study by Rixen & Dietsch (Citation2016) showed that corporate tax rates are significantly associated with country size using a sample of 110 countries in 2010. By and large, small countries do try to cash in on their advantage of size, as hypothesised by economic theory, though conclusions generally point to the structural advantage of small size being an advantage of small democracies.

Other country-specific factors that help to explain corporate tax rates, as Slemrod (Citation2004), Mutti (Citation2003), Clausing (Citation2007) and others note, is the level of individual tax rate of a particular country. CITs work as a sort of ‘backstop’ to PITs. That is, as PIT rates increase, corporations will try to reclassify labour income as general business income, to defer taxation on the personal level. Overesch & Rincke (Citation2009) found a positive relationship between the two variables.

It is reasonable to expect that there would be a relationship between revenue needs for expenditures and corporate tax rates, proxied by government expenditure as G:GDP. Slemrod (Citation2004) used this variable in explaining statutory tax rates.

Since economic integration tends to increase the mobility of capital, it is generally accepted that economic integration leads to lower taxation on corporate income. However, empirical evidence in this regard remains mixed. Earlier researchers, including Garret (1995), Slemrod (Citation2004) Clausing (Citation2007) and De Nood (Citation2012), found a significant negative relationship between openness and corporate tax burdens. This indicates that a higher level of trade or economic openness leads to higher capital mobility, and thus to a higher elasticity of capital supply.

Corporate tax rates may fall for reasons other than tax competition. Such reasons include ‘common intellectual trends’ such as the tax-rate-cut-cum-base-broadening approaches, due to concerns about the deadweight loss of taxation resulting from high tax rates (Devereux et al., Citation2005), and changes in the political climate towards a more business-friendly environment (Musgrave, Citation1990; Persson & Tabellini, Citation2000).

As previously stated, empirical evidence on CIT developments in developing economies remains scant. Most of the existing studies focus on trends in corporate tax rates and changes in tax bases. These studies include that of Keen & Simone (Citation2004), Keen & Mansour (Citation2010) and Abbas et al. (Citation2012). In the African context, Petersen (Citation2010) provided a detailed overview of the basics of the East African Community (EAC) integration and tax harmonisation process. The review highlighted the importance of harmonising domestic consumption taxes in central and western African countries towards the improved revenue positions for countries in the regions.

In the context of the SADC, a few recent studies have been published on tax coordination in the region, though these studies tend to focus on indirect taxes, such as VAT. Previous studies on taxation in the SADC (Letete, Citation2012) have largely been theoretical and have principally focused on the possibility of harmonising indirect taxes (mainly VAT). More recent studies by Ade et al. (Citation2018) show some important policy implications for the SADC (given its heterogeneous nature), aimed at enhancing the process of regional tax harmonisation.

There is a need for the SADC to develop policies aimed at collectively expanding the corporate tax base so as to accommodate the relatively low optimum CIT rates. This is of particular importance, as the adoption of lower optimum CIT rates may lead to a reduction in tax revenue. However, Robinson’s (Citation2006) study remains the only study that focused on the determinants of CIT in the SADC region.

5. Methodology

The design of a suitable model that can fully or partly explain the changing tendencies over time in CIT in the southern African region, has become essential. Before this can be done, it is important to first observe and investigate real-life data and patterns that can easily be observed on the surface. As a first step, the prevailing situation in the SADC region is detailed, so as to understand any shortcomings that may occur in the empirical analysis. The second step involves the acknowledgement of observable patterns in CIT over time. In the third and final step, the model is presented, with the intention of highlighting the causes for changing patterns in CIT over time.

5.1. Data analysis

As previously noted, taxation levels could also relate to the level of development in these countries. The level of development normally determines the size of the tax base, but also affects a country’s capacity to administer taxes. Low state capacity also reduces governments’ ability to cope with the negative fiscal consequences of tax competition. On the one hand, it becomes more difficult to police and prevent cross-border tax avoidance and evasion by rich domestic citizens and profitable companies; whilst on the other hand, given the large informal sector, it is difficult for governments to increase revenues by shifting the tax burden to labour and consumption. International tax competition thus compounds the domestic problems of raising tax revenues.

Varying degrees of development can be observed within the SADC, according to the World Bank classification. Countries such as the DRC, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe are classified as low-income developing countries. Countries such Lesotho, Swaziland and Zambia are classified as low middle-income developing countries, while Namibia and South Africa are classified as upper middle-income countries. Angola, Botswana and Mauritius are classified as low tax-rate countries, while Seychelles is regarded as a high-income country, whilst also being a low tax-rate country. Some of these countries have already started with improved tax administration efforts to broaden their tax base.

Several studies also reported changes in the effective tax burden in the region. Effective taxation relates to various aspects concerning the decision-making process to invest, namely, the user-cost of capital. Keen & Mansour (Citation2010) found that corporate tax bases have narrowed in sub-Saharan Africa, especially through the spread of tax holidays and special zones, but surprisingly, tax revenues have held steady in this region.

Several other papers have highlighted the fact that sub-Saharan Africa is an outlier in terms of changes in the tax base over time, which was on average narrower. This is attributed to the widespread use of tax incentives granted under special regimes, which has brought effective tax rates close to zero in many countries and a ‘partial race to the bottom’ (Abbas et al., Citation2012). All the countries in southern Africa have some special tax regime in place where in some instances it is brought close to zero. These trends confirm anecdotal evidence of governments in some low-income economies attempting to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) with extremely generous incentive schemes; though good governance, infrastructure and financial markets are needed for sustainable FDIs (Munongo & Robinson, Citation2017).

The above-mentioned papers, however, only report a count of the number of special regimes in a country, and do not track their generosity or calculate their impact on effective tax rates. These issues will be addressed throughout the following discussion.

5.2. Changes in CIT rates in the SADC, 1980–2017

So as to achieve an overall picture of the changing patterns and tendencies in CIT, provides an overview of the mean and standard deviation of the statutory and average tax rates. The average tax rates represent a ratio of CIT revenues-to-GDP. In this regard, it is important to continuously take all shortcomings into consideration when utilising pure statutory CIT rates.

Table 1. Changes in corporate taxation in the SADC region, 1980–2015.

The methodology used in is similar to that of Slemrod (Citation2004) and various other authors, with some minor adjustments. These calculations take the first and end figures for the calendar year and add them together, and the results are then divided by 15 to get the average. The standard deviation is then also calculated from these figures. Each pair of intervals between 1980 and 2015 is conducted only for those countries where data is available for the beginning and ending year.

5.3. Trends in tax rates: developing versus the SADC

It can be observed that developing regions, such as the SADC, have closely followed declining tendencies, which since 1985, have occurred in statutory CIT rates in the industrialised world.

In practice, developing countries have been cutting headline and effective CIT rates, as have advanced countries, but they have made tax bases narrower rather than broader. Between 1985 and 1995 the mean statutory rate fell sharply from 45 to 36%, which continued into the 1990–1995 interval. The dispersion in these rates was at its highest in the latter interval, but started to stabilise during 1990–2005, which continued until 2015. For the average CIT rates, the largest decline in the mean and standard deviation occurred during 1990–2000, with the standard deviation stabilising from 2000 to 2005. From 2005 to 2015, the statutory rate again fell to 24%.

The data for the statutory CIT rates was not available, and the average tax rates were used, meaning the tax revenue as percentage of GDP was used. Torslov et al. (Citation2018) found that between 1985 and 2018, the global average statutory corporate tax rate fell by more than half, from 49 to 24%. Torslov et al. (Citation2018) argue that profit shifting is a key driver of the decline in CIT rates. An IMF study of 2012, looked at the CIT regimes in 50 emerging and developing economies during 1996, but found no evidence of a global ‘race to the bottom’ for standard tax systems. However, for special regimes, the ‘race to the bottom’ has long taken place, with effective tax rates close to zero.

In the next section, an alternative procedure is followed in determining changing patterns and trends in CIT in the SADC region. The idea is to determine whether internal or external factors influence CIT, and whether a regime of tax competition is being followed.

5.4. Empirical model

The discussion thus far suggests that a general empirical/prospective model, as used by Robinson (Citation2006) which explains the impact of various independent variables on the statutory CIT rate, could accept the following mathematical form:

where: μ is the country dummy that represents country-specific factors; λ is the time dummy that represents the change over time; β represents the different coefficients; and X the different SADC members involved.

The data used in the pooled estimations was mostly obtained from the International Financial Statistics (Government Financial Statistics) PriceWaterhouseCoopers (Citation1980–2017), and the World Bank (Citation1980–2017). The panel covers the period 1980 to the end of 2015. It is a Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) of one tax rate measure plus a constant term. Developing regions, such as the SADC, have closely followed declining tendencies in CIT rates, as has also been observed in the industrialised world. Between 1985 and 1995, the statutory and average rate fell, but this continuous fall only gained momentum or significance from 1995 onwards ().

Various econometric techniques were tried and tested to find the most suitable for use in the study at hand. These included the so-called WITHIN and LSDV estimations, as well as random effects. Finally, the seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) analysis that takes fixed effects into account was decided upon. This technique was also recently used in other research (Ade et al., Citation2018). shows the results concerning the statutory CIT rates. The first pair regressions are pooled least-squares regressions, with the first pair having only the internal or local variables (columns 1 and 2 for SACU), and the second pair of regressions having both local and international or external variables (column 3 and 4 for SADC).

Table 2. Regressions in terms of the statutory CIT-rate (SACU and SADC). Dependant variable: Statutory CIT rate.

Although there are some shortcomings to this method, the investigation attempted to eliminate these through the SUR analysis. This analysis makes provision for any further unexplained factors through taking the error term into account. If any linkages (information) exist between countries that irreversibly bind the countries through common ground, which would most probably be the case in an economic bloc, such as the SADC, the SUR analysis would account for this. Common factors could, for instance, include high HIV-AIDS infection ratios and high absolute poverty levels.

All results delivered good R-squares, that is, well-fitted or explained models. The explanatory power of the independent variables in terms of the applicable dependent variable was thus good (see ).

5.5. Statutory CIT rates

It can be difficult to estimate the corporate tax base, as issues, such as defining depreciation, measuring capital gains, costing inventories and accounting for inflation, also require consideration. Economic or pure profits are therefore not always that clear-cut.

5.5.1. Dependent variable: CIT rates

The most common measure to use is the (top marginal) statutory CIT rate. Some studies on tax competition use effective average tax rates (EATR) as a proxy for taxing the burden. The EATR is a measurement that includes the statutory rate, as well as deductions, exemptions and other credits, and the decision-making process regarding the cost of capital.

With the above-mentioned as background, it is essential to note that not only is the ‘rent’ element important for SMMEs, but natural resource companies tend to have a high ‘rent’ (royalty) component. The SADC region has a vast natural resource base, and each country has a different way of taxing these. Some countries use differentiated CIT rates on different resources, whilst others use unique formulas designed for a specific natural resource (e.g. the tax formula used for gold production in South Africa).

The following models are used in the different columns of :

Column 1

Ln_CIT = f(ln_PIT; ln_PITNOCAP; ln_GOVEXP; SR)

Column 2

Ln_CIT = f(ln_PIT; ln_PITNOCAP; ln_GOVEXP; SR; O)

Column 3

Ln_CIT = f(ln_PIT; ln_PITNOCAP; ln_GOVEXP; ln_W; SR)

Column 4

Ln_CIT = f(ln_PIT; ln_PITNOCAP; ln_GOVEXP; ln_W; SR; O)

Where the variables can be described as follows:

Statutory corporate income tax rate [CIT]: These rates are taken from several issues of PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PWC) Corporate Tax: A Worldwide Summary. Statutory CIT corresponds to the marginal CIT rate at the top bracket for central (national) government only.

Statutory personal income tax rate [PIT]: These rates are taken from several issues of PWC’s Individual Tax: A Worldwide Summary. These rates correspond to the marginal individual income tax rate at the top bracket for the central government only.

Statutory personal income tax rate [PIT] interact with an indicator for the presence of capital gains tax [PITNOCAP]: (=1 if there is no capital gains taxation, adopting PIT value for that specific year, and 0 otherwise). These are taken from PWC’s Individual Tax: A Worldwide Summary.

The personal income tax rate (PITR), however, is expected to have a positive effect on the CIT rates. This will mainly be due to governments using the CIT as a backstop for PIT avoidance (Slemrod, Citation2004). To assess this effect, the top marginal income rates from the countries to be researched have been used. Also, the size of the economy has been included in the equation, measured by a country’s GDP. There is little consent on the size-effect in the empirical literature.

5.5.2. Internal/local variables

Central government expenditure as ratio of GDP [GOVEXP]: Government expenditures are taken from several issues of the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics. Government spending as a fraction of GDP. As explained previously, the coefficient of this variable should be insignificant.

Withholding Tax [W]: This is a tax on earnings (royalties, management fees), interest or dividend payments deducted at source. The tax is designed to simplify the collection of tax and to ensure that tax is not evaded. By taxing dividends due for repatriation, it is hoped that foreign-owned companies will be encouraged to invest in the country where its subsidiary is located.

Source/Residence principle [SR]: A dummy variable was included to describe the method of international taxation, either a source or residence principle.

5.5.3. External/international variable

Openness is expected to carry a negative sign. That is, greater capital mobility increases the elasticity of capital supply and hence drives down corporate tax rates. It is measured as the fraction of imports and exports of GDP.

Exports and Imports [O]: Exports plus Imports divided by GDP: X + M/GDP. (See World Bank’s World Development Indicator.)

In the SADC region, where withholding tax rates (from 5 to 25%, depending on the type of income involved) are still of utmost importance and double taxation agreements are rare or non-existent (South Africa has the most extensive list), it is not surprising that a strong negative relationship is present in terms of CIT rates. This could mean that these countries need to adjust their CIT rates downwards when withholding tax rates move in the opposite direction. Some double taxation agreements already exist to make provision for credits on double taxation. Another variable that is also related to this context, is the dummy variable that considers whether the country is on a source or residence (SR) system, which is significant and points to the sensitivity in terms of CIT rates.

The government expenditure-to-GDP ratio is negatively related, with the CIT rate in the pooled estimation (columns 1, 2 & 4). Though it becomes positive in the SADC region, where only local variables are used, it becomes negative as soon as the openness variable is added: This is to be expected, for the higher the spending, the more pressure there is on the CIT rates to become more competitive in terms of capital income tax systems. Only the variables for which data was available were included in this study.

The presence-of-trade variable (O) is determined as follows: [Exports (X)/Gross Domestic Product (GDP) + Imports (Z)/Gross Domestic Expenditure (GDE)]/2.

It partly gives an indication of trade openness in the region. This variable is negatively associated with the CIT rate both for the pooled and fixed effects estimators, where all international variables are present. This result could be indicative of lower CIT rates with higher trade ratios, and therefore, international pressure to lower the CIT rates. It should be taken with caution, as other factors also play a definite role in terms of a country’s openness.

Various other variables were also sourced, such as population, which showed that an increase in the population still leads to decreased CIT rates.

From it appears that there has been some pressure in the region to cut CIT statutory rates since 1985, increasing in urgency from 2005 to 2015, potentially indicating the possibility of strategic action and some tax competition.

5.6. Tax coordination not equally important in all countries

The following quotation from Ade et al. (Citation2018) is relevant:

For the countries that have large economies, good infrastructure, natural resources and attractive non-tax related FDI determinants, the case for tax harmonisation does not appear to be overwhelming. However, for countries that have small economies, poor infrastructure, relatively low levels of natural resources and less attractive non-tax related FDI determinants, the merits for tax policy harmonisation may be more appealing.

From the study, it appears that tax policies take precedence over public needs, and as such, external competitive pressure determines CIT rates. This can also be seen from a country such as South Africa, where most of the tax revenue collected is derived from personal income taxation and not corporate income taxation. Emerging and/or developing regions thus tend to under-tax capital, specifically the more elastic capital outflows.

Even in the eighteenth century, Adam Smith (Citation1776) acknowledged that capital has never been the ‘citizen of any country’. Tax havens or low tax regions have become a familiar sight in order to avoid current and future taxes, and exchange controls. Whereas the OECD and the EU lend credence to the claim of ‘harmful preferential tax regimes’, and attempt to blacklist these countries, Tanzi (Citation1995) suggests the establishment of a World Tax Organisation to deal with global tax harmonisation issues.

Countries do not appear to give much attention to their own macroeconomic environment when determining their statutory corporate tax rates. This is represented by the low level of significance of the country-specific determinants. The only effect that shows consistent significance is the effect of the PIT rate, which indicates that governments appear to use the CIT more as a backstop to the PIT. Other than this backstop effect, no consistently significant country-specific determinants were found. Indeed, corporate tax rates do not appear to be geared towards the spending behaviour of governments, as indicated by research conducted by Slemrod (Citation2004). Moreover, the effect size can be contested, because even when not including the strategic interaction variable, it is only marginally significant.

6 Concluding remarks

This paper utilised a cross-section panel (pooled and SUR analysis) to determine the factors that best explain changes in corporate taxes over time. The outcome of low taxes, namely, higher levels of capital investment, has long been questioned in literature. The main question is whether governments in developing countries, such as those in the SADC region, set their public needs first over everything else, including over inefficient tax policies that might generate uncertain revenues. If so, is it the internal public needs that determine CITs, or external competitive pressures (as part of a globalised environment)?

As noted, it is widely accepted that tax competition could have an array of consequences or outcomes. Competition in this context might lead to a natural process of tax rate convergence, and thus a limitation on the growth of governments. On the opposing side of the spectrum, it might lead to under-taxation, and consequently, an under-supply of government services and thus a ‘dilemma’. It is therefore essential to investigate whether this convergence, also in a macroeconomic sense, has been taking place and what the future outcome may hold for the SADC. In order to find a calculated outcome, it is essential to summarise the empirical results of the paper.

The main findings in this paper have delivered the following interesting results:

Firstly, the study observed that the backstop scenario is applicable both in terms of the average and statutory CIT rate. Here it makes perfect sense to accept that in countries with a higher PIT rate, the statutory CIT rate will also be higher, and that these countries will raise more CIT revenue when PIT rates increase, due to the direct link between the two rates (the differentiation between labour and business income with income linked to the GDP). Further, the PITNOCAP variable is negatively related to the statutory rate, which means that if the capital gains tax rate increases, the CIT rate will decline.

Secondly, in terms of the government expenditure variable (GOVEXP), the reality of strategic action in terms of tax competition becomes clear, irrespective the level of government expenditure. The government expenditure variable is negatively related to the statutory rate, where local and international variables are in place. It seems that tax competition prevails, whatever the level of government expenditure.

Thirdly, in the SADC region where withholding tax rates are still of utmost importance, it is not surprising that a strong negative relationship is present in terms of the statutory CIT rates. This could mean that these countries need to adjust their CIT rates downwards when withholding tax rates move in the opposite direction. The dummy variable for statutory rates (SR) becomes relevant in this context.

The fourth point is that the presence of the trade variable (O) is negatively associated with the statutory CIT rate, where all international variables are present. Although this result could be indicative of lower CIT rates with higher trade ratios, and therefore, international pressure to lower the CIT rates, it should be read with caution because other factors may also play a definite role. This also tends to confirm the region’s dependency on trade for tax revenues, especially in terms of the SACU region and its relationship with South Africa. Again, this is not an isolated issue and should also be seen in the light of capital mobility and the degree of doing business in the region.

The analysis in this paper is not final. This could mean that countries are pressurised into following competitive regimes when determining the statutory CIT rate as part of a globalised tax environment. Note should be taken of the fact that multinational companies tend to shift profits to tax havens, irrespective of the levels of corporate tax rates. The PIT base then experiences more pressure to cover public expenditure needs. With South Africa, as the so-called Stackelberg leader, the importance of sustainable economic growth needs to be emphasised. Burger (Citation2018:364) emphasises the need in South Africa for a partnership between business, labour, public interest groups and citizens, including the poor, to bring about much needed reform, excluding corruption. Economic growth in South Africa can result in economic wealth for southern Africa, and viable taxation bases for the future.

6.1. Limitations of the study

This research is not without its limitations. Firstly, this paper focused on the determinants of corporate tax rates, and not on corporate tax bases or revenues. As previously mentioned, competition using tax bases is possible; though sourcing suitable data for review of this would be very difficult, as tax laws regarding tax bases can be very complex and opaque. There are many other considerations countries evaluate when competing with others: These may include, for example, trade balances, the legal environment to set up corporations in relation to each other, historical ties between two countries, and a common language. Future research could attempt to address some of these additional factors as a more comprehensive analysis.

6.2. Implications

This paper re-emphasises the importance of international pressure in terms of future tax policymaking. At the same time, it emphasises governments’ abilities to raise taxes and thus deliver services in future. Tax cooperation or harmonisation might become the preferred route in the SADC region to ensure its attractiveness as an investment destination, and to realise the full benefit from future initiatives concerning regional integration efforts or schemes. A careful review of future tax measures and strategies by the SADC tax-subcommittee has become essential to ensure fiscal sustainability and all-importantly, macroeconomic stability increasing programmes, such as New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD).

A fine balance between domestic public needs and external competitive pressures will therefore have to be maintained in future tax policies. The main question is whether governments in developing countries, such as those in the SADC region, set their public needs over everything else, including those inefficient tax policies that might generate uncertain revenues? If so, is it the internal public needs that determine CIT, or external competitive pressures (as part of a globalised environment)?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbas, SMA, Klemm, A, Bedi, S & Park, J, 2012. A partial race to the bottom : corporate tax developments in emerging markets. IMF Working Paper 12(28), 2–31.

- Ade, M, Rossouw, J, & Gwatidzo, T, 2018. Determinants of tax revenue performance in the Southern African Development Community. ERSA (August). Accessed on 20 September 2019. https://econrsa.org/system/files/publications/working_papers/working_paper_762_final.pdf

- Burger, P, 2018. Getting it right: A new economy for South Africa. KMM Review Publishing, Sandton.

- Clausing, KA, 2007. Corporate tax revenues in OECD countries. International Tax and Public Finance 14, 115–34.

- De Nood, R, 2012. Tax Competition in the European Union: Theory and Evidence from Panel Data. http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=126916 Accessed 6 April 2015.

- Devereux, MP, Griffith, R & Klemm, A, 2005. Corporate income tax reforms and international tax competition. Economic Policy 17-35, 451–95.

- Devereux, MP, Lockwood, B & Redoano, M, 2008. Do countries compete over corporate tax rates? Journal of Public Economies 92, 1210–35.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2014. IMF policy paper. Spillovers in international corporate taxation. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2014/050914.pdf Accessed 21 January 2019.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2015. Options for low-income countries’ effective and efficient use of tax incentives for investment. Report to the G20 Development Working Group. Accessed on 24 September 2019. https://www.imf.org/external/np/g20/pdf/101515.pdf.

- Keen, M & Mansour, M, 2010. Revenue mobilization in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges from globalization. Development Policy Review 28, 553–71.

- Keen, M & Simone, A, 2004. Tax policy in developing countries: some lessons from the 1990s, and some challenges ahead. In S Gupta, B Clements & G Inchauste (Eds.), Helping countries develop: the role of fiscal policy. International Monetary Fund, Washington.

- Letete, P, 2012. Between tax competition and tax harmonisation: coordination of value added taxes in SADC member states. Law Democracy & Development 16, 119–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ldd.v16i1.7.

- Munongo, S & Robinson, Z, 2017. Do tax incentives attract foreign direct investment ? The case of the Southern African development community. Journal of Accounting and Management 7(3), 35–59.

- Musgrave, PB, 1990. Merits and demerits of fiscal competition. In Prudhomme, R (Ed.), Public Finance with Several Levels of Government, Brussels: Proceedings of the 46th Congress of the IIPF.

- Mutti, J, 2003. Foreign direct investment and tax competition. IIE Press, Washington.

- Overesch, M & Rincke, J, 2009. What drives corporate tax rates down? A reassessment of globalization, tax competition, and dynamic adjustment to shocks. CESifo Working Paper, 2535, Munich.

- Persson, T & Tabellini, G, 2000. Political economics: explaining economic policy. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Petersen, HG (Ed.), 2010. Tax Systems and Tax Harmonisation in the East African Community (EAC). Faculty of Economics and Social sciences. Department of Economics, University of Potsdam.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), 1980–2017. Corporate taxes: Worldwide summaries. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), 1980–2017. Individual taxes: Worldwide summaries. John Wiley Sons Inc., New York.

- Rixen, T & Dietsch, P (Eds.), 2016. Global Tax Goverance: What is wrong and How to fix it. doi:10.3386/w10051

- Robinson, Z, 2006. Corporate tax rates in The SADC region: determinants and policy implications. South African Journal of Economics 73(4), 722–40. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2005.00049.x.

- Robinson, Z. & De Beer. 2020. Revisiting corporate income tax determinants in Southern Africa. Working Paper. UNISA. http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/26650?

- SADC, 2019. Towards a common future. https://www.sadc.int/themes/ Accessed 4 March 2019.

- Slemrod, J, 2004. Are corporate tax rates, or countries, converging? Journal of Public Economics 88, 1169–86.

- Smith, A, 1776. An inquiry into the nature and causes of wealth of nations. JM Dent and Sons, London.

- StatsSA, 2019. A breakdown of the tax pie. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12238 Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Tanzi, V, 1995. Taxation in an Integrating World. The Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

- Torslov, TR, Wier, LS, Zucman, G, Auerbach, A, Becker, J, Bolwijn, R & Zwick, E, 2018. The missing profits of nations. NBER Working Paper Series.

- World Bank, 1980–2017. World Development Indicators supplied by Quantec.

- Zodrow, GR & Mieszkowski, P, 1986. Pigou, Tiebout, taxation, and the under-provision of local public goods. Journal of Urban Economics 19, 12–32.