ABSTRACT

This study aims to examine how car guarding remains a sustainable means of livelihood in the informal sector. The study interviewed 30 car guards at six different locations in Durban, South Africa. It examined their demographic characteristics, income, education and skills, among other factors. Furthermore, it compares the findings from 2019 with the 2015 findings from Foster and Chasomeris (2017, Examining car guarding as a livelihood in the informal sector. Local Economy 32(6), 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094217727990). The findings show deterioration in the real income levels and livelihoods. In 2015, 22 car guards earned above a domestic worker’s minimum hourly wage of ZAR15, compared to 16 car guards in 2019 and, only eight above the national minimum wage of ZAR20 per hour. There is a notable decline in expenditure on accommodation and reduced optimism about their future. Car guards still display a level of entrepreneurship, especially where daily bay fees are not paid to car guarding agents.

1. Introduction

The South African informal sector, although small in relation to the formal sector, offers alternative and long-term employment to manyof the people in South Africa. According to Fourie (Citation2018), one in six participants in the South African labour force is working in the informal sector. In absolute terms, this implies that about 5 million people were employed in the informal sector before the onset of the COVID 19 pandemic in 2020 (Francis & Valodia, Citation2020). One such informal sector activity is car guarding.

Car guards offer to guard motorists’ vehicles at either private or public parking areas for a donation (Steyn et al., Citation2015). Car guarding remains predominately a South African informal sector employment activity (Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017). The origin of car guarding, according to Arde (Citation2014), occurred at a Durban beachfront in 1996, when an unemployed individual was asked by a motorist to guard his car in exchange for a small donation. What distinguishes car guarding from other means of informal economic activities is that the amount of the donation is generally at the motorist’s discretion.

Bernstein (Citation2003) noted that car guards fulfil more of a public service role rather than a private service role such as waiters. Therefore, the option of tipping is unique and suggests a desire to reward good service, yet there is no personal obligation. Car guarding is therefore an unusual combination of market economics of rewarding work well done, and the good nature of the public. Furthermore, motorists may tip simply due to their own internalised feelings of wishing to help others (Saunders & Petzer, Citation2009; Saunders & Lynn, Citation2010; Steyn, Citation2018).

Unemployment in South Africa remains high and a challenge for the country. The results of the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) for the third quarter of 2020, released by Statistics South Africa, indicate that the official unemployment increased to 30.8%, from 23.3% in the second quarter of 2020. The expanded unemployment rate, for Quarter 3, however, was 43.1% for South Africa and 47.5% for KwaZulu-Natal (Statistics South Africa, Citation2020). The impact of the COVID 19 pandemic is clearly felt in the labour market and will also have short- and long-term consequences for the informal sector.

In addition to increasing unemployment, the South African economy cannot accommodate the vast number of migrants entering our borders, and thereforecar guarding remains a viable means to earn a living due to low entry barriers (Daniel et al., Citation2010; Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017).

Although authors such as Steyn et al. (Citation2015), Foster & Chasomeris (Citation2017) and Steyn (Citation2018) found that car guards represent the more marginalised components of South African society, the more formalised car guards, and especially those based at areas where repeat motorists frequently park, do manage to earn a relatively stable income. What often hampers this ability to survive on tips is the daily bay fees car guarding agents demand from car guards. These agents simply regulate car guards by providing pre-allocated parking bays for a daily bay fee. As car guards are not employed by the agencies, they receive no salary, paid leave, sick leave and very few, if any, benefits.

Some believe car guards are part street-corner entrepreneurs and part meter attendants (Spinks, Citation2012). Other authors believe car guards offer no real value and are simply a nuisance or another form of begging (Aberdein, Citation2014). It has been documented that some more informal car guards may well be involved in crime, and therefore the drive by the Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority (PSIRA) to better regulate and ultimately formalise car guarding, as per Nair (Citation2015), and Foster & Chasomeris (Citation2017). Formalised car guards are regulated by agents, or premises’ management, and expected to be far more responsible, and often vetted by the South African Police Service (SAPS) to ensure they have no criminal record (McEwen & Leiman, Citation2008).

However, car guarding is still considered in terms of preventative measures to be a very effective means of combating crime, even more effective than patrol cars or closed-circuit television (Steyn et al., Citation2015). McEwen & Leiman (Citation2008) noted that although car guards are seldom able to actively fight crime, as they usually carry no weapons and have no means to apprehend a criminal, their very presence can deter criminal activity.

The aim of this study is to examine how car guarding remains a sustainable means of livelihood in the informal sector. The study interviewed 30 car guards at six different locations in Durban, South Africa. The demographic characteristics, income, education and skills, risks and challenges faced, and the opinions of car guards regarding their livelihood were further examined and compared to the 2015 findings from Foster & Chasomeris (Citation2017).

2. Literature review

2.1. Livelihood of car guards in the informal sector

The South African informal economy has a relatively small informal sector compared to other developing countries (Kingdon & Knight, Citation2001). Broadly defined, the informal economy includes the self-employed individuals in informal enterprises (i.e. small businesses with unregulated workers) as well as the wage employed workers in informal jobs (i.e. unregulated and unprotected workers) in both urban and rural areas (International Labour Organisation (ILO), Citation2002; Chen et al., Citation2005). Casual or temporary wage workers, such as car guards and day labourers, have no fixed employer and sell their labour (human capital) on a daily or seasonal basis, often as a last resort (Makaluza, Citation2016). In addition, informal workers are denied workplace protection with little or no workplace health and safety standards, employment rights such as minimum wages, annual leave, paid holiday and sick leave and training (Chen, Citation2012).

In addition, according to Kistan et al. (Citation2020), informal workers in general have worse self-reported health statuses than formal workers and are often being discriminated against at clinics (McLaren et al., Citation2013). Missing a day at work equals a loss of income, and transport costs add to the plight of informal workers.

Many workers earn such low wages, they cannot satisfy their most basic needs; this is defined as working poverty and is not unique to South Africa (Huysamen, Citation2018). Tokman (Citation2001) and Nelson & Bruijn (Citation2005) noted that informal workers simply provide income opportunities for the poor, as with lower tier informal car guards.

2.2. Regulation of informal sector car guards

In Durban alone, there may be more than a thousand car guards and usually a clear distinction exists between the more smartly dressed, formally regulated car guards, and informal unregulated car guards. Unregulated car guards usually pay little or no daily fees and, often include homeless street people, who usually patrol public domains. Regulated car guards usually pay daily bay fees to the agencies that are expected to ensure their car guards receive training and are regulated (McEwen & Leiman, Citation2008). These organisations have no contract with, nor do they employ car guards, often only selling, or providing the needed jackets and security equipment on a hired basis and demand that car guards pay daily fees (Steyn et al., Citation2015; Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017).

Numerous news articles, such as Athman (Citation2019), reported that unregulated car guards demanded R10 to watch cars in Pietermaritzburg, and Phakgadi (Citation2018) reported how a car guard stabbed a motorist in the street for not paying a tip. These unregulated car guardsseem to be more likely to be aggressive or defensive towards motorists and the public. In addition, some may also be involved in public indecency and threaten the public.

Throughout South Africa, there are examples of initiatives to better regulate car guards. For example, Kalk Bay municipality is in the process of formalising car guards, spearheaded by local businesses, with the intention of reducing potential crime associated with unregulated car guards (Kotze, Citation2017). Simon’s Town Community Policing Forum (CPF) has taken the initiative further by launching a project to better train and then offer employment to car attendants in collaboration with law enforcement agencies (McCain, Citation2017).

2.3. PSIRA drive to formaliseinformal sector car guards

Section 20 of the Private Security Industry Regulation Act (Act 56 of Citation2001) states that all car guards are required to complete a one-week basic security and security-related training course before registering with the Private Security Industry Authority (PSIRA) with a Grade E security certificate. Given the concern regarding illegal and therefore unregulated car guards, who may well be involved in crime, PSIRA’s new legislation to better formalise car guards has merit, but the financial cost to attend the training and pay the monthly registration fee is for the car guards’account as they are classified as independent workers (Steyn et al., Citation2015; Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017). Many car guards cannot afford these amounts. Furthermore, the terms illegal and legal car guards refer to their legal status in terms of complying with PSIRA regulations and having a minimum-security Grade E. In addition, legal car guards should have name tags and branded shirts or bibs and be vetted by the South African Police Service (SAPS) to ensure they have no criminal record. In addition, car guarding agents are liable to a fine if they allow unregistered car guards to work (Lindeque, Citation2017).

The efforts to formalise informal and illegal car guards have brought with it possible additional direct costs for car guards who may not be able to continue as informally active. The theoretical (and policy) implication is that well-intended attempts to formalise the informal economy without a participatory process with the informal workers themselves may in fact jeopardise lives and livelihoods. This finding is confirmed by Schenck et al. (Citation2019) where similar efforts to formalise the operations of informal collectors of recyclable material on some landfills have often led to deteriorating earnings and longer hours of work for the collectors (Schenck et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, this can further question the informal sector’s perceived role as a shock absorber in case of economic distress as has been propagated by mainstream development theory (Francis & Valodia, Citation2020).

2.4. Exploitation of informal sector car guards

As far back as 2003, Rondganger (Citation2003) reported that PSIRA had issued warnings to unregistered guards to register with PSIRA or face possible arrest. In December 2018, a joint sting operation by PSIRA and the South African Police Services (SAPS) resulted in the arrest of 36 carguards and their employer at Sanlam (Pinedene) shopping centre in Pinetown, Durban. As reported by Singh (Citation2018), these car guards were not registered as security guards with the required minimum Grade E training. Arrests were also made at Windermere Centre and the China Mall in Springfield Park in Durban. To bypass the required PSIRA registration and therefore also not having to pay car guards security Level E monthly wages (R4 102 (2018 rates) in major metropolitan areas and R3 414 in other areas) (SA Government News Agency, Citation2018), the car guarding agents now provide car guards with new branded bibs advising they are customer trolley assistants (CTA), not car guards. In addition, these car guards still need to pay daily bay fees to the car guarding agents.

Steyn et al. (Citation2015) found that most car guards struggle to survive financially as bay fee tariffs must be paid to car guarding agencies or the owners of shopping centres daily. In addition, these amounts are paid, mainly irrespective of the car guards’ daily income. This was also noted in studies by McEwen & Leiman (Citation2008), as well as Foster & Chasomeris (Citation2017).

2.5. Representation of informal sector car guards

Cohen & Moodley (Citation2012:320) noted that the fundamental goal of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) is the achievement of ‘ … decent and productive work for both women and men in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity.’ Decent work is more than simply a source of income, but a source of personal and family stability, and the opportunity for economic growth due to productive employment (International Labour Organisation (ILO), Citation2010). Yet, car guards in the lower tiers of the informal sector are unable to benefit from these standards. Informal workers, especially workers such as car guards, are vulnerable due to the absence or minimal employment relationships or contracts, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. According to Fourie (Citation2008), in theory, under current South African labour legislation, these individuals should be protected; however, in practice, their unusual employment circumstances render the enforcement of their rights problematic.

Car guards, by the very nature of their dispersity, vulnerability and the regulations imposed on them by car guarding agents, are unable to form any representative associations. Consequently, the struggle to earn a minimum wage that allows car guards to get out of poverty is not an option.

2.6. Survivalist pursuit of informal sector car guards

Some intrepid car guards offer additional services, for example Durban car guards at the new pier have been nick named ‘the guardian angels’, as they, in addition to guarding vehicles, also SMS surfers daily regarding surfing conditions and keep surfers’ keys while the motorists are out surfing (Arde, Citation2014; Hentschel, Citation2015; Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017). Car guards also forge good relations with business owners and assist by keeping storefronts and parking lots clear of vagrants (Christie, Citation2009). Nicolson (Citation2015) found that car guards in Johannesburg may wash cars to supplement their income. This also occurs elsewhere in South Africa (Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017).

3. Research methodology

Interviews were conducted with 30 car guards located at two shopping centres, two hospitals and two public beachfronts in Durban, between June and August 2019, as per the previous study done in 2015. The same shopping centres and beach front sites were re-visited. One of the hospital sites visited in 2015 no longer has car guards, and therefore was replaced by an alternative hospital that is very similar in terms of size, location, demographics and socioeconomics.

The interviews were semi-structured with both open- and closed-ended to allow for in-depth information about the livelihood of car guards. The themes were therefore predetermined based on the set of questions used by the first author in completion of the author’s master’s dissertation in 2015. The same themes were again used to allow comparison between the findings from 2015 and 2019. The themes as well as the research method were based on the format used by well-published authors on car guards, such as Blaauw & Bothma (Citation2003) and Steyn (Citation2018).

All the car guards were eager to be interviewed and interviewed individually, face-to-face, and encouraged to answer the questions in detail, to better understand the perceptions of their livelihood, their concerns and opinions. Each car guard signed an informed consent form agreeing to be interviewed and audio recorded. Ethics clearance to conduct the study was acquired from the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Potential limitations were anticipated, namely misunderstanding due to language barriers; car guards’ reluctance to being interviewed; and the study being limited to Durban. The concern was that as the interviews were conducted in English, and for many car guards, English would be a second or even third language, there could be misunderstanding of the questions. However, all car guards had enough understanding of English to answer all questions. Although not required, copies of the interview scripts were translated into Zulu and French in case any questions were not understood. Efforts were made to explain questions clearly, while ensuring that the questions were not leading. As the study was limited to only six different sites and only conducted in Durban, this study is not an accurate representation of KwaZulu-Natal or South Africa, yet provides a general indication of the current situation.

The duration of each interview was approximately 20 min. In total, close to ten hours of audio-recorded data was collected, transcribed and then analysed using coding to identify emerging themes. The findings are summarised and discussed in the next section.

4. Key findings

4.1. Car guards: demographic characteristics and incomes

compares the profiles of randomly selected car guards interviewed in 2019 as relating to the 2015 study by Foster & Chasomeris (Citation2017).

Table 1. Profile of car guards interviewed in Durban, 2015 and 2019.

indicates that male car guards still outnumber female car guards substantially. The mean age of car guards has dropped at all sites but the hospitals. The average car guard now works just under six days per week, yet still works an average of just short of nine hours per day, and the average income for car guards now ranges from ZAR13 to ZAR19 per hour. Average daily incomes ranged from as little as ZAR108 to ZAR161. A domestic worker in Durban theoretically can earn ZAR20 per hour in 2020. The legislation stipulates a national minimum wage rate of ZAR20 per hour, or ZAR3 500 per month, depending on the number of hours worked. As reported by De Wet (Citation2020), as of 1 March 2020, the rate has increased by 3.8% to ZAR20.76, although this rate is still in the process of being challenged by the trade unions in South Africa who demand a bigger increase.

The earnings of car guards depend on the tips they receive from motorists. The respondents were asked to indicate the smallest single tip they received. The smallest was a mere five cents (reported by 4 out of the 30 respondents). The maximum value of this variable was ZAR2.50 with a median of 50 cents. When asked what the biggest single tip was, the responses ranged from ZAR5 to ZAR400, with a median of ZAR100.

As one car guard noted on the beachfront ‘we leave at 6 and (bad) people come and sit in cars and they know we leave then so no one to look after cars’. Even though the beachfront has a high volume of traffic, car guards at these venues are unable to retain the same level of earnings in terms of real value as in 2015. One car guard, an icon with Durban surfers and beach goers, who has been guarding cars for 26 years, noted that ‘ … people are tired of people asking for money at every street corner, car guarding is taking a bit of a nose dive, we earn less now.’

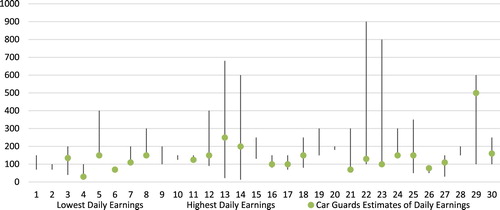

shows car guards’ lowest, highest and estimated daily earnings. The large range of earnings indicates how uncertain and volatile car guards’ potential earnings are. The average (mean) of the lowest daily income is ZAR82.53 and the median ZAR75. The respondents were also asked to report on their highest income earned per day. This ranged from ZAR70 per day to ZAR900, with a mean of ZAR360.67 per day and a median of ZAR225.

Figure 1. Car guards’ income 2019 (lowest, highest and estimated daily earnings in ZAR).

Note: Several car guards were unable to provide their estimated daily incomes.

Car guards labelled one to ten are based at two shopping centres in Durban, where the first five do not pay any daily bay fees, while car guards six to ten pay R35 daily bay fees. Their daily earnings are relatively low as the shopping centres are both based in middle to lower income areas near Umbilo. Only six car guards managed to earn ZAR300 or more at the high end of their earning potential.

Car guards labelled 11 to 20 are at two private hospitals in the Glenwood area in Durban. Car guards labelled 11–15 pay daily fees ranging from ZAR17 to ZAR35 a day, depending on where they are located, while car guards labelled 16–20 patrol the public road outside the second hospital and do not pay daily fees. Car guards labelled 21–30 are on the Durban North and South Beaches, respectively. The North Beach car guards (labelled 21–25) can earn substantially more as they are situated near restaurants and have specialised in keeping car keys of surfers, and often SMS surfers early in the morning regarding the surf (sea) conditions. These car guards refuse to pay the (CPF) Community Policing Forum ZAR5 a day, due to vagrants taking the tips from motorists and even threatening the car guards. The agents are unable to regulate the vagrants. A car guard noted that ‘we are often threatened by beggars, we chase them away and they threaten me that they wait for us tonight. Told I have a hit on my life for ZAR50’. The South Beach car guards (labelled 26–30) earn less than the North Beach guards as they rely more on the beachgoers. Most estimate their average daily earnings to be closer to their lowest daily earnings, and this reiterates the uncertainty of their daily income and the financial plight of South African car guards.

In 2015, shopping centre car guards in Durban worked an average of 5.4 days per week, 8.5 h per day earning an average of ZAR11.57 per hour. In 2019, working an average of 5.4 days per week, slightly fewer hours of 8.3 h per day and earn an average hourly income of ZAR13. Hospital car guards, in 2015, worked an average of 5.6 days per week, 9.9 h per day, earning an average of ZAR15.3 per hour. In 2019, they work an average of 5.8 days per week, and 9.5 h per day earning an average of ZAR16.2 per hour. Beach front car guards worked an average of 6.4 days per week and 10.3 h per day, earning an average of ZAR15.9 per hour. In 2019, they work an average of 6.1 days per week, 8.4 h per day and earn an average of ZAR19.1 per hour. Therefore, in real income values, all car guards are earning less than in 2015.

In terms of expenditure on accommodation, in 2019, nine car guards paid between ZAR1 000 and ZAR1 999 per month rent, unlike 15 in 2015, eight paid between ZAR2 000 and ZAR2 999 per month compared to 13 in 2015, four paid between ZAR3 000 and ZAR3 999 compared to one in 2015 and none paid between ZAR4 000 and ZAR4 999 rent per month, unlike one in 2015. Therefore, nine paid less than ZAR999 a month in 2019 compared to only one car guard in2015. The increased cost of living and lower income earned by most car guards force many to settle for cheaper accommodation.

In 2019, only two car guards owned their own small rural dwellings unlike eight in 2015. In addition, seven car guards live in either a squatter camp or in rooms that are either unfit for human occupancy or have no electricity or sanitation. This may well be related to the fact that accommodation is getting more expensive and shelters are not always clean or safe, with people’s clothes often stolen. This was confirmed by three of the interviewed car guards who had their clothes stolen this year at a shelter when they left the dorm room to take a shower.

When comparing the level of education, it was noted that 24 car guards (80%) in 2019 had completed primary school (grade 7), unlike 26 (86.7%) in 2015. In 2019, six foreign car guards had started studying in their home country, yet had not completed their studies due to political strife, unlike threeforeign car guards in 2015.

In both 2019 and 2015, no car guard in the two Durban surveys had completed any tertiary studies. Although these findings are like those of McEwen & Leiman (Citation2008), who found that many foreign nationals enter South Africa with higher qualifications, whereas few local car guards have completed their schooling. This may well be becauseSouth African car guards with tertiary studies may find better employment.

Unlike 2015 where only one car guard had done any PSIRA training, in 2019 a total of nine car guards had PSIRA training of at least an E grade, and all these car guards were regulated by agents. These car guards where predominantly all car guards for many years and predominately white, with only two Zulu car guards having completed their PSIRA grading.

4.2. And challenges faced

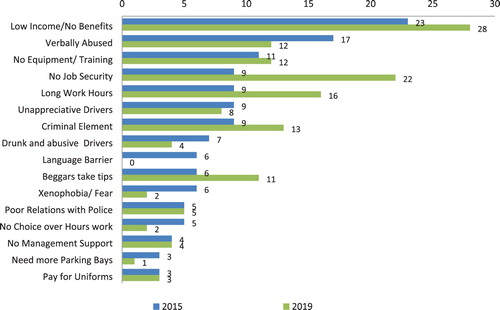

examines the risks and challenges that car guards face in performing their duties in 2019 as compared to the 2015 study.

shows that 28 car guards compared to 23 in 2015 are now concerned about the low income and no benefits, with one car guard mentioning, ‘we use to make up to R500 a day now we struggle to make R100. People have bad attitude towards us now’. Another car guard stated that ‘the country is going down, not get more like before, things are bad’.

In addition, having no equipment or means to protect themselves against armed carhijackers who are becoming more aggressive and increasingly stealing cars; the long hours worked; the lack of job security and beggars that don bibs and steal car guards’ tips are the biggest challenges and concerns of car guards. In 2019, two car guards at one of the hospitals had witnessed cars being stolen. On the beachfront, one car guard related how a car had been hijacked and guns had been produced and pointed at the car owner and car guard. The car guard explained this harrowing situation as follows: ‘I want to tell you the truth, the owner was there and I was there, he just parks the car, and he jump out car. When I try to go to the owner, they just pull a gun, then the owner come stand here and me too stand here. They reverse car, then we just keep quiet, scared, never do nothing, just stand and look, and car is vei (gone)’On a lighter note, he mentioned that he needs training ‘to protect me so if someone shoots I know how duck a bullet’.

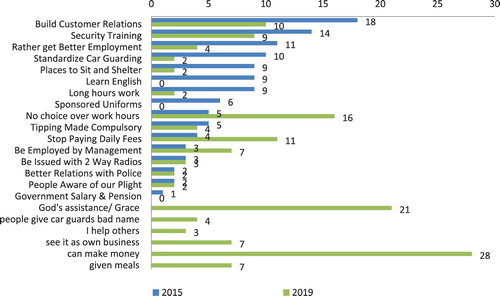

refers to the concerns car guards raised relating to their livelihood.

Figure 3. Car guards: Opinions regarding their livelihood, 2015 and 2019. Source: 2019 data from this study and 2015 data from Foster & Chasomeris (Citation2017)

4.3. Entrepreneurial spirit of informal car guards

In 2019, 22 (73.3%) of the car guards realised the need to build relations with customers to receive higher tips, higher than 18 (60%) in 2015. Christie (Citation2009) noted that car guards in Cape Town often build customer relations and therefore forge strong relations with business owners. Aberdein (Citation2014) and Nicolson (Citation2015) noted that car guards build customer relations and offered value-added services to customers, such as washing cars. One car guard summed up the need for customer relations by stating ‘it’s customer based, everyone needs a parking and a car to get into when they come back, I get cash because I have a smiley face and always wave hello and help.’ Another car guard who earns a more sustainable income at one of the hospitals mentioned: ‘It’s money every day, this is my business, customers come to me, but it is bad that we have to pay bay fees’.

Formalised car guards often build good relations with clients, such as beach front car guards who look after surfers’ car keys (Arde, Citation2014; Hentschel, Citation2015; Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017). Car guards often earn the trust and respect of motorists and therefore benefit financially from these relationships. In addition, several car guards, especially migrants, mentioned that they save up money from car guarding to buy and resell clothes or electronic goods to earn additional income.

4.4. The frustration of daily fees

Bay fees and the sheer unfairness of paying daily to work were a grave concern to 11 (37%) car guards in the 2019 study compared to four (13%) car guards in 2015. One car guard mentioned ‘paying day fees is cutting our throats’. Another car guard reasoned that ‘nobody pays to work yet if I do not pay to work, they will just get the next ou (person). ‘It may well be that car guards have resolved to make the best of the situation, as car guard agencies have full control in this power relationship, and car guards have no trade union or other recourse.

4.5. The reliance on a higher power for direction and wisdom

Twenty-one (70%) car guards specifically noted the importance of God in their lives and their dependence on God to overcome their many challenges. A car guard noted that ‘without God we cannot make it (car guarding)’, another car guard mentioned ‘God must be there else we won’t make it’.

5. Further discussion

Car guards have not received much attention in recent literature (Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017). This study contributes as it documents and assesses car guarding as a means of livelihood in the informal sector. There are three main themes that emerge from this research that deserve further discussion. These themes to be discussed below are: (1) formalisation, (2) automation and pay for parking, and (3) income levels and livelihoods.

5.1. Theme 1: formalisation

The South African informal sector for years has been seen by provincial and local policymakers as a sector with little growth, even a ‘problem sector’ due to zoning and urban planning difficulties. Another view may be that it is part of the apartheid legacy and not the modern economic landscape (Rogerson, Citation2015; Fourie & Kerr, Citation2017). PSIRA regulations as well as new legislations to regulate the informal sector affect car guards. After years of existing to provide a service to the community, as well as to earn an income in the informal sector, car guards are still forced to pay daily bay fees (Steyn et al., Citation2015; Foster & Chasomeris, Citation2017). Car guards need to be offered the opportunity to complete the required PSIRA Grade E certification so that they are better informed about how to handle potential emergencies and break-ins. The move by PSIRA to formalise security agents and directly provide an income to car guards has been circumvented by the agents who have simply renamed car guards as customer trolley assistants (CTA) at several shopping centres. In addition, car guard agents and to a lesser extent the shopping complex management need to be regulated, so that car guards are not forced to pay daily bay fees to guard cars in a predetermined area. With better regulation of car guards, this will also result in informal car guards being vetted and the criminal aspect to be regulated.

5.2. Theme 2: automation and ticketed pay for parking

The introduction of automated boom gates and pay for parking at several hospitals and shopping malls has resulted in a decline of the traditional car guarding services. Several malls and hospitals have introduced automated boom gates and ticketed pay for parking facilities that have resulted in many car guards losing their ‘jobs’ or livelihoods. However, the loss in livelihoods and income is not uniform across locations. For example, at one of the hospital locations in 2015 the hospital used several car guards, but by 2019 there were no longer any car guards as the hospital has converted to using a security guard at the exit to check whether keys were in the vehicle when leaving the premises and, more recently ticketed automated boom gates have been installed. At another hospital location in this study, in 2015 there were several car guards offering their services and by 2019 the hospital had installed ticketed pay for parking boom gates, but had retained the services of some of the original car guards. Consequently, even though these car guards have retained their employment, customers are required to pay for the parking tickets and so the incomes received by the car guards have significantly declined. Furthermore, with such changes to their working environments, these car guards fear for the future of their livelihoods. The informal sector and some of its activities are evidently also vulnerable to exogenous structural adjustments to the environment they function in – as illustrated through the car guard experience.

5.3. Theme 3 income levels and livelihoods

The evidence from this study shows that there has been a general deterioration in the income levels and livelihoods of car guards between 2015 and 2019. A combination of factors has caused the deterioration in livelihoods. These factors include: the deteriorating economy exasperated by COVID 19, which has resulted in further economic recession and significantly reduced employment in both the formal and informal sectors; the pressures of formalisation (partly through the activities of PSIRA, and partly due to car guard agents), and the introduction of automated boom gates and ticketed pay for parking facilities that no longer require the services of car guards. Such trends have not only resulted in loss of livelihoods for car guards, but also show the reduced opportunities and possibilities of car guarding as a sustainable livelihood.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to examine informal sector car guarding as a sustainable means of livelihood. The study interviewed 30 car guards at six different locations in Durban, South Africa. The average car guard interviewed is 42 years old, has been guarding cars for nine and a half years, works five and a half days per week for an average of nine hours per day. In addition, only nine car guards had completed the compulsory Private Security Industry Regulatory Agency Grade E security training, unlike only one in the 2015 study.

The findings show a dramatic deterioration in their real income levels and livelihoods. There is reduced optimism about the future livelihoods of car guarding, with verbal abuse, violence and possible health risks as concerns. The regulation of daily bay fees as well as better management of car guarding agents also needs to be urgently addressed. There is a need for the public and all interested stakeholders to better understand the challenges and contributions of car guards.

The themes forthcoming from the study also guide us to consider the possibility that the informal sector’s theoretical role as shock absorber in times of crises may be in fact limited in South Africa. This, however, does not diminish the critical role of the informal sector in providing livelihoods for millions of South Africans (Fourie, Citation2018). This is a relatively small study, but suggests that more local research is needed to better understand the theoretical and practical role of the informal sector in South Africa. Revisiting informal employment (in line with the work of Heintz & Posel (Citation2008)) with more focused research will facilitate an improved theoretical understanding of the unique nature of the South African informal sector. Car guarding, for example, was not in evidence when mainstream development economic theories on the informal sector were developed. From a theoretical perspective, the development of a-typical activities, e.g. car guarding, necessitates a reconsideration of the standard view of segmented labour markets. We argue in line with and Uys & Blaauw (Citation2006) that segmentation can also occur within the informal sector itself and not merely between the formal and informal sector – as is often accepted. Studies that focus on informal economic activities such as car guarding will enhance our understanding of the labour market challenges faced by so many of South Africa’s citizens in their quest to earn a living and hopefully provide a future for their children and the next generation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the 30 car guards who agreed to be interviewed, for the giving of their time and for so openly sharing their life stories with us. Most of all, we greatly respect that these men and women who have faced much hardship and still do, refuse to revert to the easier cowardly option of crime. We salute your perseverance. We also thank the reviewers and editor for valuable comments and suggestions on earlier drafts. The usual disclaimer applies. Above all, we acknowledge and give honour to Jesus Christ without His undertaking, no change will occur.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aberdein, M, 2014. Beggars wearing yellow vests: Cape Town’s car guards entrepreneurs. http://www.mattabbo.com/blog/cape-town-car-guard-entrepreneurs Accessed 20 September 2015.

- Arde, G, 2014. Durban’s car guards get corporate: Next City. https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/durbans-car-guards-get-corporate Accessed 20 September 2015.

- Athman, B, 2019. Hostile car guards an issue in town. News24. https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/local/maritzburg-fever/hostile-car-guards-an-issue-in-town-20190115Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Bernstein, J, 2003. Car watch: Clocking informal parking attendants in Cape Town. Centre for social science research, social surveys unit. Working Paper 55(13), 1–32.

- Blaauw, PF & Bothma, LJ, 2003. Informal labour markets as a solution for unemployment in South Africa: A case study of car guards in Bloemfontein. South African Journal of Human Resource Management 1(2), 40–44.

- Chen, M, 2012. The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. WIEGO Working Paper No. 1. Manchester, WIEGO.

- Chen, M, Vanek, J, Lund, F, Heinz, J, Jhabvala, R & Bonner, C, 2005. The progress of the world’s women 2005: Women, work and poverty. United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), New York.

- Christie, SH, 2009. The secret lives of Cape Town’tas car guards. http://www.seanchristie.co.za/articles/the-secret-lives-of-cape-towns-car-guards/ Accessed 22 November 2015.

- Cohen, T & Moodley, L, 2012. Achieving “decent work” in South Africa? Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad 15(2), 320–344.

- Daniel, J, Naidoo, P, Pillay, D & Southall, R, 2010. New South Africa review 2010: Development or decline? Wits University Press, South Africa.

- De Wet, P, 2020. New minimum wage in South Africa. Business Insider South Africa. https://www.businessinsider.co.za/new-minimum-wage-in-south-africa-2020-2020-2 Accessed 15 June 2020.

- Foster, J & Chasomeris, M, 2017. Examining car guarding as a livelihood in the informal sector. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 32(6), 525–538. doi:10.1177/0269094217727990

- Fourie, ES, 2008. Non-standard workers: The South African context, international law and regulation by the European Union. Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad 4, 110–152.

- Fourie, F, 2018. Creating jobs, reducing poverty III: Barriers to entry and growth in the informal sector – And business cycle vulnerabilities. http://www.econ3(3.org/article/creating-jobs-reducing-poverty-iii-barriers-entry-andgrowth-informal-sector-%E2%80%93-and-business Accessed 10 November 2020.

- Fourie, F & Kerr, A, 2017. Informal-sector employment in South Africa: An enterprise analysis using the SESE survey. REDI Working Paper 32 (March 2017). http://www.redi3×3.org/sites/default/files/Fourie%20%26%20Kerr%202017%20REDI3×3%20Working%20Paper%2032%20Informal%20sector%20employment%20and%20SESE.pdf Accessed 28 October 2020.

- Francis, D & Valodia, I, 2020. South Africa needs to focus urgently on how COVID-19will reshape its labour market. https://www.wits.ac.za/scis/publications/opinion/sa-needs-to-focus-on-how-covid-19-will-reshape-labourmarket/ Accessed 10 November 2020.

- Heintz, J & Posel, D, 2008. Revisiting informal employment and segmentation in the South African labour market. The South African Journal of Economics 76(1), 26–44.

- Hentschel, C, 2015. Security in the bubble: Navigating crime in urban South Africa. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

- Huysamen, E, 2018. The future of legislated minimum wages in South Africa: Legal and economic insights. De Jure 51(2), 271–297.

- International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2002. Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture. International Labour Office, Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_626831.pdf Accessed 15 June 2020.

- International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2010. South African decent work country programme 2010-2014. https://www.ilo.org/africa/countries-covered/south-africa/WCMS_227655/lang–en/index.htm Accessed 10 October 2011.

- Kingdon, GG & Knight, J, 2001. Why high open unemployment and small informal sector in South Africa? Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, University of Oxford. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4ca5/a3a73018fb58a2de59e62dc510140fca92a0.pdf Accessed 16 November 2020.

- Kistan Jesne, Ntlebi Vusi, Made Felix, Kootbodien Tahira, Wilson Kerry, Tlotleng Nonhlanhla, Kgalamono Spo, Mathee Angela, Naicker Nisha, Duplaga Mariusz, 2020. Health care access of informal waste recyclers in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One 15(7), e0235173. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235173. Accessed 1 November 2020.

- Kotze, K, 2017. Image make-over for car guards. False Bay Echo. https://www.falsebayecho.co.za/news/image-make-over-for-car-guards Accessed 11 June 2018.

- Lindeque, B, 2017. South Africa stories: Insight to being a female car guard, GOODTHINGSGUY 28 May 2017. [Blog]. https://www.goodthingsguy.com/opinion/car-guards-south-africa/ Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Makaluza, N, 2016. Job seeker entry into the two-tiered informal sector in South Africa. REDI3(3 Working Paper No.18. http://www.redi3(3.org/sites/default/files/Makaluza%202016%20REDI3(3%20Working%20Paper%2018%20-%20Job%20seekers%20in%20two-tiered%20informal%20sector.pdf Accessed 1 November 2020.

- McCain, N, 2017. Homeless set up as car guards People’s Post. https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/Local/Peoples-Postlhomeless-set-up-as-car-guards-20170626 Accessed 15 June 2018.

- McEwen, H & Leiman, A, 2008. The car guards of Cape Town: A public good analysis. South African Labour Development Research Unit Working Paper Series 25, 1–24.

- McLaren, Z, Ardington, C & Leibbrandt, M, 2013. Distance as a barrier to health care access in South Africa. https://www.google.com/search?q=McLaren+Z%2C+Ardington+C%2C+Leibbrandt+M.+Distance+as+a+barrier+to+health+care+access+in+South+Africa.+2013.&oq=McLaren+Z%2C+Ardington+C%2C+Leibbrandt+M.+Distance+as+a+barrier+to+health+care+access+in+South+Africa.+2013.&aqs=chrome..69i57.5926j0j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 Accessed 11 June 2020.

- Nair, N, 2015. Call for car guards to get training and an official ticket. http://www.timeslive.co.za/thetimes/2015/06/18/Call-for-car-guards-to-get-training-and-an-official-ticket Accessed 20 September 2015.

- Nelson, E & Bruijn, E, 2005. The voluntary formalization of enterprises in a developing economy? The case of Tanzania. Journal of International Development 17, 575–593.

- Nicolson, G, 2015. Men in the street: Of car guards and daily (poverty) grind. Daily Maverick. Cape Town. http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2015-03-17-men-in-the-street-of-car-guards-and-daily-poverty-grind/ Accessed 20 September 2015.

- Phakgadi, P, 2018. Joburg car guards urged to refrain from forcing motorists to pay for parking Eye Witness News. https://ewn.co.za/2018/09/09/joburg-car-guards-urged-to-refrain-from-forcing-motorists-to-pay-for-parking Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Private Security Industry Regulation Act 2001 (Act 56 of 2001), Pretoria: GovernmentGazette. http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/num_act/psira2001451.pdf Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Rogerson, C, 2015. Unpacking national policy towards the urban informal economy. In J Crush, A Chikanda & C Skinner (Eds.), Mean streets: Migration, xenophobia and informality in South Africa. Southern African Migration Programme, Waterloo, Canada, 229–248.

- Rondganger, L, 2003. Durban car guards get a last-minute reprieve. iolnews. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/durban-car-guards-get-a-last-minute-reprieve-.104322 Accessed 12 September 2015.

- Saunders, SG & Lynn, M, 2010. Why tip? An empirical test of motivations for tipping car guards. Journal of Economic Psychology 31(1), 106–113.

- Saunders, SG & Petzer, D, 2009. Consumer tipping: A study of the car guarding industry. Paper presented at Anzmac 2009, Australia, 30 November - 2 December 2009.

- Schenck, R, Blaauw, D, Viljoen, K, Swart, R & Mudavanhu, N, 2019. The management of South Africa’s landfills and waste pickers on them: Impacting lives and livelihoods. Development Southern Africa 36(1), 80–98.

- Singh, K, 2018. Unlicensed car guards get arrested. The Mercury News iolnews. https://www.iol.co.za/mercury/news/watch-unlicensed-car-guards-get-arrested-18377229 Accessed 4 April 2019.

- South African Government News Agency, 2018. Republic of South Africa Security officers to get salary increase. https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/security-officers-get-salary-increase- Accessed 1 June 2020.

- Spinks, R, 2012. Conversations with Cape Town car guards. Matador Network. http://matadornetwork.com/abroad/conversations-with-cape-town-car-guards/ Accessed 8 November 2015.

- Statistics South Africa, 2020. Quarterly labour force survey. Statistical Release P0211. Pretoria, South Africa. Quarter 3 2020 http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02113rdQuarter2020.pdf Accessed 19 November 2020.

- Steyn, F, 2018. Fleeing to exploitation: The case of immigrants who work as car guards. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 58(4–2), 925–939.

- Steyn, F, Coetzee, A & Klopper, H, 2015. A survey of car guards in Tshwane implications for private security policy and practice. SA Crime Quarterly 52, 15–24.

- Tokman, V, 2001. Integrating the informal sector in the modernization process. School of Advanced International Studies Review 21(1), 45–60.

- Uys, MD & Blaauw, PF, 2006. The dual labour market theory and the informal sector in SouthAfrica. Acta Commercii 6, 248–257.