?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

South Africa lags behind among other developing and emerging market economies on business start-ups. Businesses that fail in a year is averaging between 50% and 60%, a figure quite high for a country struggling with achieving sustainable economic growth to reduce unemployment, inequality and poverty. This study identifies issues hurting SMMEs that need attention from both businesses themselves as well as from policymakers. The objective of this study is to identify key business success determinants using cross-sectional data that was randomly collected from informal businesses in Johannesburg/Pretoria in South Africa from 390 informal SMMEs. Using assets ownership as a yardstick for success in an ordered logistic regression, the study finds education status, income, employment growth, centre of operation, financial inclusion, experience, financial literacy and advertising budget were significant in explaining assets ownership (success) in South Africa. This study recommends that the government through its various institutions that deal specifically with small businesses come up with radical business training programmes so as to improve the finance literacy among small business. Also, small business owners should budget to fund their advertising budgets since it is found that advertising has a positive impact of firm success.

1. Introduction

Small micro and medium enterprises (SMMEs) are defined as businesses that employ less than 50 employees (McPherson, Citation1996; Rocha, Citation2012; Ndayizigamiye & Khoase, Citation2020). South Africa is currently in the midst of disappointing economic growth patterns, with an ever increasing unemployment rate, poverty and inequality. The country also lags behind other developing countries on small business start-ups. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) 2013 report insists that eight out of every 100 adults start and own a business that is less than 3.5 years old. On average other developing countries are ranging from 14 to 16. GEM (Citation2014) articulates that only 2.3% of South Africans own businesses that are older than 3.5 years. These are indications that the small business failure rate is very alarming in South Africa. To further indicate the failure rate of small businesses in South Africa, especially among starts-ups, South Africa ranks 41st out of 43 countries in the prevalence rate for established businesses (GEM, Citation2015).

It is also estimated that the failure rate of small, medium and micro enterprises (SMEs) is between 50% and 60%. Millions are being spent on business ventures but, because of a wide range of factors starting from the individual owner of the business to the general business environment in the country, most of the businesses fail within a period of 5 years (GEM, Citation2014). It is maintained often that the ideas are good and the people behind them are competent, but they do not have much experience when it comes to the technical knowhow to run a business and most of the people have been observed as not having the underlying appreciation of business fundamentals (Brink, Citation1997; Barron, Citation2000; Mokoena, Citation2017). Problems encountered by small businesses are numerous and can be described amongst others as being environmental, financial or managerial in nature.

The objective of this paper is to probe and identify key success indicators among black owned businesses in South Africa. The authors noted in literature that in Africa an issue of great significance for policy development surrounding small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) point towards finding the determinants of successful SMEs (Rogerson, Citation2000). Evidence from a range of international studies points to the fact that while entrepreneurs are generally not in short supply in most African countries, only a small fraction of new enterprises will ‘graduate’ from birth to become small enterprises with more than 10 workers (Kamitewoko, Citation2013; Shibia & Barako, Citation2017). In southern African research, it is estimated that only 1% of new micro-enterprises will make the transition to a successful established small enterprise (Gillani & Khan, Citation2013). Despite their small numbers, this group of growing and successful SMEs is viewed as offering a critical contribution to the policy goals of employment creation, promotion of inclusive economic growth and poverty alleviation (Maduku and Kaseeram Citation2019). A critical issue for policy becomes understanding those factors which will cause some firms to grow to become successful small enterprises, thus creating sustainable or long-term employment opportunities. Hence, the focus of this study rests on the interest to investigate the determinants of informal small business success for policy intervention so as to expand the number of successful SMMEs in South Africa.

The contribution of this study to the body of knowledge is on establishing a success indicator that can be used to judge if an SMME is successful or not successful. Assets ownership was regressed against a number of independent variables to see what determines the ownership of assets in South Africa, which is a yardstick for success. The foundation assumption of this study is that businesses that own assets or that have acquired assets stand a better chance to access credit that can be used for further growth prospects and general expansion of the business. When a business expands and grows its capital base, more workers will be demanded for output to grow. That is exactly what South Africa currently needs to move out from a number of socio-economic problems it is faced with, such as unemployment, poverty and inequality.

2. Review of related literature: theoretical literature

Over time, there has been an increase of literature that tries to understand and analyse business growth. If we pay attention to neoclassical economics, O’Farrell and Hitchens (Citation1988) reiterate that growth of a firm is generally enabled by declining short run cost curves leading to increased savings that then accrue from unit costs that become lower (Kamitewoko, Citation2013). Whilst explaining firm growth, O’Farrell and Hitchens argue that productivity of variable factors of production, for example labour, was limited by the fixed factors of production such as capital (Kamitewoko, Citation2013). According to iterations from O’Farrell and Hitchens (Citation1988), growth of a firm is technologically, wage and lastly price driven. The argument follows the belief that more workers are included into production to increase output up until the marginal product of labour becomes equal to the wage rate (O’Farrell & Hitchens, Citation1988; McPherson, Citation1996; Phelps & Wijaya, Citation2020).

One of the pioneers among other theories was the work of Gibrat (Aguilar & Kimuyu, Citation2002). The Law of Proportionate Effect (LPE) by Gibrat (Citation1931) explained firm growth as a random experience that had nothing to do with firm size. Firms could grow despite their size or despite existing policies in a certain country (Yadav et al., Citation2020). McPherson (Citation1996) referred to firm growth as stochastic models, explaining that those firms that are ‘lucky’ could actually continue to make high profits in the long-run. Thus, McPherson and Gibrat assume that firms could grow independent from size and policies, putting an emphasis on luck and other attributes that differ from one firm to another.

Contrary to the theories of Gibrat and McPherson, there is another school of thought that attributed firm growth to availability of benefits that accrue from better management of factors of production at firm level. Coase (Citation1937) argued that firms that are more productive and cost-efficient grow better. If a firm could manage to reduce production costs, exchange and transaction costs then it stood better chances to grow. This theory points to the economic importance of emergence of firms and management structure. Firms stand better chances to grow if firms were more efficient and they face low running costs whilst getting better supply prices for inputs (labour and capital) (Coase, Citation1937). In agreement with Coase’s theory, the famous theory of firm growth by Penrose (Citation1959), which adumbrates that firm growth is basically driven by resources ranging from efficiency and capacity for managers to plan and forecast. This theory does not dismiss the paramount importance of external factors but it emphasised that if internal factors are well in place, it will be fundamental to exploit external factors to promote firm growth (Penrose, Citation1959).

Another school of thought posited that firm growth depends of firm age and business opportunities available. The life cycle theory of the firm by Mueller (Citation1972) is of the view that businesses grow slowly during their early ages of existence, the growth rate increases then slows down again as the firm reaches maturity because of diminishing profitable opportunities in the market. Mueller’s theory believes that the growth pattern of firm follows an S-shape as the firm grows into maturity. So if the business owner or the business managers are not vigilant enough to plan and forecast, the maturity of the firm as far as growth is concerned can be premature if there are new entries that come in with new offers that are better than what the firm is offering (Mueller, Citation1972; Stepanyan, Citation2012).

Jovanovic’s (Citation1982) theory is contrary to the Law of Proportionate Effect (LPE) from the perspective that firms are believed to learn from the past so that they improve on efficiency. Efficient firms survive and grow at a faster rate whilst those that do not collapse and shut down. The theory of ‘noisy selection’ by Jovanovic underscores on the effect of managers that are inefficient. The inefficiency of managers was attributed on their lack of experience in production optimisation (Jovanovic, Citation1982; McPherson, Citation1996). The theory of noisy selection assumes that, with time, managers will gather sufficient experience to plan better and to become more efficient. However, as managers accumulate experience, as firms grow both in age and size, the cycle will then turn to diminishing growth as new experiences and innovations impact on the business together with the market where the firm is operating (McPherson, Citation1996).

To summarise, engaged theories were divided into two distinct category variables that are believed to influence firm growth. One part of the theories underscored the importance of internal factors to foster growth of firms (Penrose, Citation1959; Jovanovic, Citation1982). The other distinct group of schools of thought emphasised on the importance of external factors that happen to drag and limit firms to grow (Penrose, Citation1959; Mueller, Citation1972; O’Farrell & Hitchens, Citation1988; McPherson, Citation1996). To clearly investigate the determinants of firm growth and success, this paper then has to include both internal and external factors that facilitate firm success.

2.1. Empirical literature

In this section we focus on previous work that tried to identify and solicit key drivers of small business success. Iyer and Schoar (Citation2008) look at the market for wholesale pens in India amongst three different ethnic groups. Consistent with Penrose (Citation1959) on the impact of internal factors, they found the one group, known for being particularly having a deep business culture was better at fostering long-term business relationships especially within their own community than other ethnic groups. Santarelli and Tran (Citation2013) show that human capital strongly predicts firm success with learning really showing a statistically significant positive association with operating profit. On the other hand, benefits from strong ties outweigh those from weak ties, interaction of human capital and social capital displays a statistically significant positive effect on new-firm performance. The former talks much about the importance of social capital and business network. This is much of a skill that can be developed into business people so that they can start to network their business ideas and benefit from social capital.

There is also evidence of a positive link between education and training and successful SMMEs. This is from a limited exploration of the determinants of success in a sample of emerging manufacturing SMMEs in Western Cape, South Africa. Sawaya (Citation1995) concluded that the rate of success was highly correlated with the level of education attained by the owner. This finding is in line with the World Bank (Citation1993) report which indicated a direct correlation between education and turnover in SMMEs. Specifically, this investigation concluded that entrepreneurs who had achieved a Standard 10 level of education had average turnover nearly twice of those who had completed Standard 8. Interestingly that was the status of the majority of SME entrepreneurs in South Africa (World Bank, Citation2014). Conforming findings from World Bank (Citation1993) and Sawaya (Citation1995), on common characteristics that foster business success among South African businesses, education was also identified as an important factor for businesses to graduate from the micro-enterprise seedbed into the formal economy (Ebony Development Alternatives, Citation1995).

Supporting the neoclassical economics of diminishing returns to variable production factors in the short run, productive capacity of firms is affected by variables that impact on their productive capacities. On the impact of external factors, Neves et al. (Citation2009) identified successful enterprises as those with relatively stable access to markets, with access to capital from outside sources (either from Non-Governmental Organisations then in rare cases from banks) and run by entrepreneurs with capacity to innovate and take risks. In regards to entrepreneurship, the major findings related to success of enterprises with owners who had prior industry experience usually with larger enterprises and to the fundamental importance of a basic level of education as well as some essential technical knowledge (Neves et al., Citation2009). The study found the importance of technical experience on top of being on educated with theory educated. It further argues that, it is not significantly enough for a small business owner to be good with classroom theories but should have been hands on in business. The argument in Neves’ paper is that, if a person has been involved hands on in business, chances are that the person will be familiar with processes of procurement, management of finance, management of stock and business risks involved. That will make a business person familiar with the market, improving on key decisions that have to be made whilst running the business.

Some of the early studies into democracy of South Africa found evidence of a positive relationship between success of SMMEs and the entrepreneurs’ level of skills and training. The conclusion was based on manufacturing SMMEs in Gauteng (Rogerson, Citation2000). As a result of the apartheid system, the majority of South Africa’s population had not been socialised or educated to become entrepreneurs, but rather to enter the labour market as waged employees (Visser, Citation1997). This situation underpins the problems faced by emerging black entrepreneurs in the face of competition from groups of well-educated and multi-skilled immigrant entrepreneurs who have been establishing production SMMEs in the post-apartheid period (Rogerson, Citation2000). It is against this background of existing South African research on successful SMME development that attention now turns to the industry case study.

To conclude, heterogeneity of sectors has also been identified as a variable that affects firm growth and success in Kenya. SMMEs that operate in construction, services, chemicals and plastic sectors were identified to be experiencing growth compared to other sectors (McPherson, Citation1996). These differences per sector in terms of growth can be attributed to specific transformations that exist in the structure of the economy. Mead and Liedholm (Citation1998) underscores the fact that certain sectors are prioritised and subsidised the most in other economies, hence they may proliferate compared to other sectors that can impact on firm growth and success. Andre (Citation2015) posits that certain differences in growth among economic sectors may be attributed to outright inducements that are from potential growth in demand or may be that can be explained by the invention of totally new products that respond to the dynamic needs of the market.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Conceptual framework

This study is a quantitative study which will use evidence from small businesses. Corporate or Business success is measured in so many dimensions determined by both internal and external resources ranging from labour expertise and availability of market opportunities (McPherson, Citation1996). It is assumed that businesses that operate in highly competitive markets increase output of their productions until a point where marginal costs (MC) of production equals Marginal Revenue (MR). Production of firms in the short run reaches a point where there are diminishing returns to inputs of production such as labour. Small businesses are labour-intensive, hence they keep employing labour up until the returns from employing one more unit of labour equals the wage of that extra employee hired. Bond et al. (Citation2015) iterates that when firms suffer from credit/financing constraints, their opportunities for expansion are stifled and that as a result negatively impacts their growth and success prospects. To add, when firms are operating in an environment which is costly to invest it can lead marginal costs (MC) to increase at a very high rate such that firms arrive at profit maximisation output with lower quantities as compared to an environment that is cheap to invest in.

Considering the fact that SMMEs are human capital intensive, if we view both physical and human capital as resources that are complementary to each other in production, resources that an entrepreneur possesses, such as experience in business and education attained, are assumed to have a positive impact on the productivity of a given physical capital (Shibia & Barako, Citation2017). Joint ownership of firms is also believed to contribute to growth and success through specialisation and sharing notes. Innovative firms are also argued to expand the absorptive capacity of technology through networking, productivity improvement and exacerbated growth of firms (West & Bogers, Citation2014). To see the relationship of investment environment to firm success, , let us assume that the success of the firm is proportional to its new investment,

, that is:

(1)

(1) So in this case, all new investments come from either internal profits or borrowing. In the case that there is no credit from external sources, investment from saved income will be;

(2)

(2)

is the firm’s net profit and is a function of net income of operations, financing and investing costs.

is the portion of net income distributed to the entrepreneur for external uses. In the case that there is external credit lines:

(3)

(3)

is the amount of external credit. Equation (1) can be rewritten as:

(4)

(4) In this case, any factor that negatively impacts on

will lower firm success.

affects

directly through expansion of capital and indirectly because it reduces profits saved for reinvestments through high interest rates.

3.2. Data issues

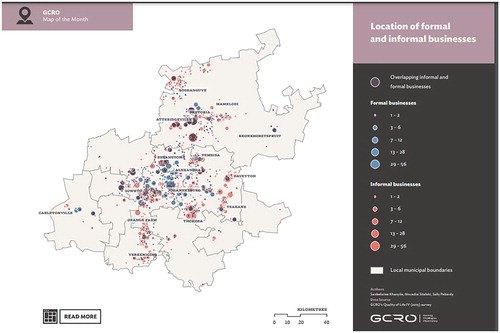

The analysis is based on cross-sectional data gathered from informal SMMEs in Johannesburg/Pretoria area in South Africa. Johannesburg and Pretoria are the joint capital cities of South Africa situated in the Gauteng province. The study area was chosen because it is the national hub of economic activity in the country as well as these cities serving as the capital cities of the country. The area is home to an estimated 1,210,475 SMMEs, of which more than 60% of those are not formally registered (SEDA, Citation2015). The majority of the SMMEs in the research area are concentrated in clusters depending on the nature of businesses and that is indicated by the annexed map (). The evidence of businesses concentration both formal and informal can be explicitly found from the 2015 survey contacted by Gauteng City-Region Observation (GCRO) Quality of life survey (GCRO, Citation2017). The survey clearly outlines the towns under the municipalities of Johannesburg and Pretoria that have high concentration of both formal and informal SMMEs. The high concentrated areas considered by this paper are shown in the below;

Figure 1. Johannesburg and Pretoria SMMEs concentration. Source: GCRO (Citation2015).

Using a questionnaire, data was collected from areas that are highly concentrated, with informal SMMEs shown in . The considered areas were marked as high concentration zones of informal business activities on a map published by Gauteng City Region Observatory (GCRO). The distribution of informal businesses in the visited area is shown on the map in .

Table 1. High SMMEs concentrated zones.

In addition, this paper focused on areas with economic activities that are highly concentrated with informal businesses. These economic activities have also been found by statistics South Africa as the major contributors to the Gauteng economy through its interlinkages with both formal and informal businesses (Statistics South African, Citation2015b). This research concentrated much on the four clusters of economic activities that are highly likely to attract more SMMEs, especially those that are operating informally. shows the clusters that will be targeted.

Table 2. Distribution of economic activity in Gauteng Province.

3.3. Sampling and sample size selection

Gauteng province is an area which is multilingual but there are three major languages which are Tswana, Zulu and English. The questionnaires used were translated from English to the other two indigenous languages so that those who did not understand English could understand the questionnaire. The majority of the informal businesses that were visited were identified as operating in sectors or in high concentrated zones. Given that fact, a clustered random sampling technique was used so that SMMEs in all the clusters get equal probability of being interviewed (Cresswell, Citation2014). The cluster sampling technique involves the researcher dividing the population into separate groups, called clusters. Thereafter, a simple random sample of clusters is selected from the population and thus the data analysis is conducted from the sampled clusters. The economic activities that were considered in this research are manufacturing, wholesale and retail, transport and lastly other services. Questionnaires were handed out depending on the size of each and every economic activity involved in this study, as publicised by Statistics South Africa (Citation2015a). That background led us to distribute 31% of the total questionnaires to manufacturing, 26% to wholesale and retail, 25% to the transport sector and 18% to others services. Gauteng province has an estimated number of close to 700 000 informal SMMEs and 550 100 SMMEs that are operating, formally complying with all the rules that guide businesses in the country. In choosing our sample size, the study borrows from Alvi (Citation2016) and Stattrekcom (Citation2016). In an area with 700 000 SMMEs, the formula calculates 385 as the appropriate sample of these SMMEs.

3.4. Variable description

Gender: The sex of the business owners. The sex was measured as (1) male, (2) female and (3) other.

Business type (bustyp): The ownership status of the businesses involved in the research. Measured as (1) sole proprietors, (2) partnerships and (3) family business.

Sector: This simply identifies the sector in which the SMME is operating in: (1) manufacturing, (2) wholesale and retail, (3) transport and (4) other services.

Education: The highest education attained by the business owner: (1) primary, (2) secondary/matric, (3) tertiary and (4) other.

Income: Average monthly sales received by businesses measured as (1) for income below R10 000, (2) sales between R10 000–R30 000 and (3) sales above R30 000.

Assets ownership: The nature of assets ownership by the business. The criteria of ownership were measured as (1) acquired fixed assets, (2) renting assets and (3) if the business cannot afford but using the street or backyard.

Experience: If the business owner had acquired business experience before establishing his own business. It was measured as (1) if yes and (0) if otherwise.

Capital source: Seeking to understand where the business accessed capital to start the business and was captured as (1) bank, (2) family, (3) savings and (4) other sources.

Financial literacy: Establishing if the business owner has the skills to prepare accounting/financial statements. It was captured as (1) high, (2) good and (3) very little knowledge.

Advertising: Establishing if the business had a budget set aside annually for advertising its business. It was captured as (1) for those who always have a budget, (2) for those who have it sometimes and (3) for those who never have it.

Employee growth: Established if the number of employees has increased or decreased since the first year of operation. Captured as (1) yes (increased), (2) decreased and (3) remained unchanged.

3.5. Model specification

This paper used a categorical dependent variable and an ordered logit (ologit) model by Powers and Xie (Citation2008) to estimate determinants of informal SMME success in South Africa. We measure success using assets ownership. The variable was coded (1) if the business owns fixed assets for operation, (2) if the owner is renting assets and (3) if the owner uses back yard. If the business owns assets, it is regarded as highly successful. If they rent assets, the business is regarded as moderately successful. Lastly, if the business is using the backyard, the business is regarded as the least successful.

Now let us assume that we have the following model:

(5)

(5) where Y* is unobserved, the Xs are the regressors and

is the error term.

is sometimes referred to as a latent variable.

In the event that we have independent firms and they are facing j-ordered alternatives, such that:

(6)

(6)

where

.

That is, we observe a specific private firm in one of the

ordered categories, where categories of these private firms will be made separate by some threshold parameters, for example

or

. It is also important to note that the ordered logit model estimates not only the coefficients of the X regressors but it also produces or creates the threshold parameters (Gujarati, Citation2011). The slopes of the coefficients of the X regressors will not be different for all the categories but the intercepts will be different. However, we will end up having parallel regression lines that are anchored on different intercepts.

3.6. Estimation procedure of the ordered logit model (OLM)

All multinomial models are estimated by the method of maximum likelihood, so is the ordered logit model. When estimating an ordered logit, we want to estimate;

(7)

(7) Thus, equation (7) reflects the cumulative probability that

is in category j and below, for example in category 1, 2 … upto j. If we are to come up with a random variable that takes a value equal to or less than the number provided, we use the cumulative distribution function (CDF). Also in order for us to estimate an ordered logit model, the disturbance term (

) should follow a logistic distribution as opposed to when it follows the normal distribution (Gujarati, Citation2011). When it follows the normal distribution we obtain an ordered probit model. In this case we want the residuals to follow a logistic distribution.

To compute cumulative probabilities as shown in equation (7), we use the following:

(8)

(8) Equation (8) is the CDF of the logistic probability distribution. BX is there to represent

. The regressor on the ordered logit dependent variable becomes nonlinear because it is channeled through the nonlinear CDF. When that happens, the interpretation of the ordered logit can become complicated to interpret but to make it easy we use the odds ratios. The left hand side of equation (6) reflects the ordering of the response scale and it is standard to then consider the odds ratios that are defined by the following equation

(9)

(9) where

(10)

(10) Equation (10) denotes the cumulative probability that the outcome is less than or equal to

. So we use the logistic CDF as given in equation (8) to come up with odds ratios in equation (9) then take the log of these odds ratios to obtain the following;

(11)

(11)

Equation (11) will thus give a sequence of logits and in our case we have to have three such logits. The logits should have the same regressors and the same slope or coefficients. However, the only things that will be different are the intercepts.

3.7. Limitations of the model

The model estimates one equation over all levels of the dependent variable in our case assets ownership with three categories but the only difference will be the cut-off points or we can call them intercepts. That will be the reason why we will obtain parallel regression lines for the different levels of our dependent variable. However, we can test this assumption after running the model to see if the coefficients are the same. This can be done using the (Omodel and Brant) tests that can be run by the statistical package software (Stata).

4. Results and discussion

In presentation of the results, provides details about the demographics and descriptive statistics of the 380 respondents, followed by an analysis of the results. Thereafter, reports the ordered logistic regression results, and the ensuing discussions thereof.

Table 3. Demographic and descriptive statistics of respondents.

Table 4. Ordered logit regression output.

Referencing , out of 390 SMMEs involved in this study, 51.54% of them were male owned whilst 48.46% were female owned. In terms of their educational status, there are four categories in which they were meant to fit in. Statistics from those categories reveal that 27.18% completed primary school only, 51.03% of the responses managed to complete matric (secondary education), those who completed tertiary education as well as their postgraduate education were 17.95% of 390 SMMEs included in the study and, lastly, those who did not have anything of the above were a paltry 3.85%. In an effort to understand the type of businesses that are thriving in the study area, we found that 53.85% were sole proprietor businesses, while 18.46% were partnerships and 26.92% came out to be family businesses. However, 0.77% of the responses did not indicate the type of businesses they were running. The other point of interest was to understand how those businesses were funded in the first place. The capital source for most businesses were their savings which constituted 43.08%, while those funded by capital raised from family members were 39.23% and those that received capital from banks and other sources were 13.33% and 4.36%, respectively. The manufacturing sector is most attractive to small businesses in the study area and it contributed 40.77% to the responses of this study, while retail and wholesale were 22.05% of the 390 SMMEs, 21.03% reported that they were working in the transport sector and 16.15% reported that they were involved in the business of other services like hairdressing and food catering.

On another important aspect of business, advertising budget, we established that 53.85% of businesses have never advertised nor have a budget specifically for that. However, there are those who sometimes have this budget which are 32.82%, then 13.33% confirmed that they always have the budget meant for advertising their businesses and products they are offering. According to the findings of this study SMMEs in the Johannesburg/Pretoria area are struggling to earn significant profits, as only 5.12% of those sampled earned an income in excess of R30 000 per month, while 67.18% of the respondents earned an income of R10 000 or less per month. When it comes to assets ownership, 23.85% have managed to acquire their own assets for operation, while 30.26% are renting assets from other people and 45.64%, which is the majority in this case, cannot afford to acquire or to rent assets but they use the street or backyard of their houses to operate their businesses. To add, financial literacy has been cited as one of the biggest challenges SMMEs are facing. In our study, we found that 48.21% reported that they had little understanding of preparing financial statements and budgets. However, 37.18% responded in the appropriate section of the questionnaire that they were ‘good’ in preparing and understanding financial statements. However, interestingly, 14.62% of the respondents reported a ‘very high’ competency in preparing and understanding financial statements. Lastly, our findings reflect that 54.10% of our sample did not have business experience when they started engaging in business. It was only 45.90% of them who were engaged in business activities before starting their own operations.

After using the ologit command of stata 13, we found results that are shown in the table 4 above. However, before the interpretation of results is done, the researcher will take you through the overall results of the estimated model. Given the null hypothesis that, under ordered logit, all regressor coefficients are zero, the LR test follows the χ2 distribution with degree of freedom equal to number of independent variables (14 in this case) (Gujarati, Citation2011). The χ2 value is about 167. If the null hypothesis happens to be true, the chances of obtaining a χ2 value of as much as 167 or more are almost non-existent. We can conclude that the explanatory variables have enough influence on the success probability. Also the model shows a Pseudo R2 of 0.2425. This is not the same as the usual R2 in OLS regression that we use to measure the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables included in the analysis. Also to add, under the logit the statistical significance of the regression coefficients is determined by the Z-value, which is the standard normal distribution of Z. Eight of our 14 variables are significant except business network (bisnet), capital source, business branches (bizbranch), profit growth (profgrow), sector of operation (sect) and business type (bustyp).

4.1. Interpretation of results

The coefficients from regression in the table 4 above are ordered log-odds or logit coefficients. In this section we will only interpret those variables that were significant in explaining success of SMMEs using assets ownership as an indicator for success. The dependent variable has three categories: (1) acquired assets (this is regarded as highly successful), (2) rent assets (this is regarded as moderately successful) and (3) can’t afford/use backyard (this was regarded as not successful or the least successful). Our findings suggest that if we increase education level by one category, for example from metric to tertiary education, the ordered log-odds of being in the high success category increases by about 0.66 (66%), holding all other independent variables constant. This implies that if one moves a step up in the education category, there is the probability of moving from operating in the backyard to starting to rent assets with all being constant. Education has been cited as one of the major problems affecting the smooth running and growth of SMMEs in the developing world (GEM, Citation2015). Another related finding to education is financial literacy of SMMEs that operate in the Johannesburg/Pretoria area. If financial literacy increases to an upper category, the odds in favour of a higher success category over a lower category of success are greater than 1. In other words the odds increase by 371%. Financial literacy is an important skill that businesses need to possess if they are going to survive because they will be skilled enough to handle their finances as well as budgeting and stock management (Mwirigi et al., Citation2019).

Another important variable in the literature and in our findings is income. Our results indicate that the odds of moving to a higher success category increases as income received by black-owned SMMEs increases say from the category of getting less than R10 000 a month to getting between R10 000 and R30 000. The same also happens when an entrepreneur starts receiving more income, for example moving from getting between R10 000 and R30 000 a month to getting an income above R30 000. The odds increase by 0.4374 or 44% of the income received by SMMEs increases. This implies that success increases as income increases and decreases the more income decreases. SMMEs that have challenges to penetrate markets, lack advertising budgets and lack finance related skills are prone to receiving lower incomes and that decreases the odds of their success, and Sefiani (Citation2013) also found the same results.

The odds of moving to a higher success category increase as SMMEs manage to secure budgets that are specifically meant for advertising their businesses. If advertising increases by one category up for example, from never to sometimes, the odds of moving to a higher success category are more than 1. According to , the odds increase by 195%. This is how marketing and advertising budgets are important to SMMEs that operate in the Johannesburg/Pretoria area. In order to penetrate the market, SMMEs need to be capacitated so that they can be able to sustain competition from bigger businesses and those that are in the same line of operations with them. Competition has been cited as one of the biggest challenges that small business face in South Africa (Mukumba, Citation2014). Some small businesses close down as they fail to sale mostly because they are failing to compete. Hence, increased capacity towards advertising and marketing might help SMMEs to be resistant to competition shocks and improve the odds of their success.

Table 5. Ramsey RESET test using powers of fitted values.

Another interesting finding from our ordered logit model (OLM) is experience of SMME owners in business. This variable seeks to understand the impact of experience on success. The findings indicate that if experience increases by one category, that increases the odds of moving to a higher success category by 0.4785 or 48%. Those SMMEs owned by people who have had experience in business somewhere stand higher chances of being successful by at least 48% compared to those that are owned by entrepreneurs who have not accumulated experience somewhere and these results confirm the work of Islam et al. (Citation2011). On another note, since SMMEs are mostly labour intensive in their operations, the odds of moving to a higher success category when employees have increased since the first day of operation are higher. In other words, if employees increased, the odds of moving to a higher success category are more than 1. Employee increment as opposed to being constant or decreasing, increase the odds of going to higher success category by 157%. This implies that SMMEs that see their employees increasing overtime stand better chances of being successful than those that are with constant or decreasing employees. The benefits attributed to increasing labour are at least attributed to the theories of O’Farrell & Hitchens (Citation1988) and McPherson (Citation1996).

Lastly, other determinants of success, as identified by our findings reported in , are the centre of operation and financial inclusion. When a business has a place of fixed abode, that increases its chances of being trusted by clients as well as convenient in terms of operations. We found that odds of moving to a higher category of success increase by 69% if a business has a centre of operation like an office. That also reflects that if a business does not have a centre of operation, the odds of moving to a higher success category are lower by almost the same percentage (Islam et al., Citation2011). Also according to , those SMMEs that have secured credit or funding from any financial service institution increase its odds of moving to a higher success category by 37%. This is one of the most important variables in the developing world, mainly because small businesses struggle to secure credit. If a business cannot access credit, this implies that basically it cannot grow. The problem of financial exclusion of small business cuts across all types of SMMEs (informal and formal). Details to this high rate of exclusion are explained by different authors ranging from lack of collateral security (Mwirigi et al., Citation2019), the inability to run finances (budgeting) (Chowdhury & Alam, Citation2017) and the inability to draft business proposals and high risks that small businesses bear (World Bank, Citation2016). However, government policies have shifted already hoping that SMMEs are going to contribute significantly towards economic growth, job creation and poverty alleviation. This cannot be achieved at least in the context of South Africa where close to 60% of small businesses collapse before they reach 3.5 years of existence. One of the most cited causes of the increasing mortality rate of small businesses is lack of credit. Something needs to be done so as to improve credit access for small businesses, especially black-owned SMMEs that represent the bigger part of the population, which is characterised by massive poverty, unemployment and is heavily marginalised in the South African economy.

4.2. Diagnostic tests

On our diagnostic tests we start by interpreting the RESET Test Results at 5% significance level, we fail to reject the null hypothesis of correct specification. This means that the functional form is correct. Therefore, we conclude by saying that our model was correctly specified.

Here we interpret the Pearson goodness of fit which assesses the discrepancy between the current model and the full model. It tests if the predicted probabilities deviate from the observed probabilities in a way that the model does not predict. If the p-value for the goodness of fit test is lower than the chosen level, the predicted probabilities deviate from the observed probabilities in a way that the model does not predict. If the p-value is not significant at 5% then the model has enough prediction power to yield reliable coefficients. shows that the p-value for Pearson is not significant at 5% (0.05), which indicates that our model is correctly fit.

Table 6. Goodness of fit for multivariate.

The Wald test confirmed if there is a relationship between the independent variables and the depended variable. The hypothesis that we test is that the relationship between the explanatory variable and the dependent variable is zero (0), meaning there is no relationship. We fail to reject the null hypothesis when the p-value of the χ2 is above 5% (0.05). If the p-value of the χ2 is below 0.05, as is our case in , we reject the null the hypothesis and argue that there is a relationship or the independent variables are explaining the dependent variable enough.

Table 7. Wald tests for multivariate case.

5. Conclusion and policy recommendations

The objective of this study is to identify key determinants of business success in South Africa using cross-sectional data. Continuous failure of small businesses in developing countries limits the contributions of SMMEs towards Gross Domestic Product (GDP), unemployment and poverty. Given the fact that 50–60% of SMMEs in South Africa, especially those that are black-owned, close down before reaching 3 years of existence. This means that the country is having more businesses that are in their formative stages and this limits the number of businesses that graduate from small to being large businesses so as to contribute towards sustainable employment in the country. Using cross-sectional data from SMMEs in Johannesburg and Pretoria in South Africa, the research identified the firm specific factors that explain firm success. Firm specific factors identified are owner’s education, owner’s financial literacy, business age, experience, income, advertising budget and employee growth. On external factors affecting informal SMMEs, access to capital was found to be one of the determining factors for firm success. Findings of the owner’s education and years of experience confirm the resource-based theory of firm growth by Coase (Citation1937). Findings on the impact of business experience on firm growth and success also confirm conclusions from Shibia and Barako (Citation2017). Some of the recommendations arising from the findings of our study point to small business owners to save so that they can fund their advertising budgets, since it is found that the availability of advertising has a positive impact of firm success. Also financial literacy was found to be one of the factors contributing towards firm success. We recommend that there be a partnership between government (Department of Trade and Industry), Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and Universities to come up with SMMEs business training centres equipped with programmes targeted at improving skills such as financial literacy and operations management among small business owners in South Africa. Also the South African government should consider forming an SMME Bank that harnesses financial resources for improving access to capital/credit for small businesses so that the success rate of small businesses can be improved.

5.1. Suggestions for future research

The current study analysed data from mainly four sectors, namely manufacturing, wholesale and retail, transport and services. Hence, to come up with more comprehensive and conclusive findings more sectors involved in informal businesses in South Africa can be considered.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aguilar, R & Kimuyu, P, 2002. Firm growth. In A Bigsten & P Kimuyu (Eds.), Structure and performance of manufacturing in Kenya. Palgrave, New York, NY, 192–205.

- Alvi, MH, 2016. A manual for basic techniques of data analysis and distribution. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. https://mpra.ub.unimuenchen.de/60138/.

- André, L, 2015. Structural change, sectoral specialisation and growth rate differences in an evolutionary growth model with demand shocks. Journal of Innovation Economics & Management 1(16), 217–48.

- Barron, C, 2000. Brilliant ideas but spectacular flops. Sunday Times Business Times, 9 April, p. 1.

- Bond, EW, Tybout, J & Utar, H, 2015. Credit rationing, risk aversion, and industrial revolution in developing countries. International Economic Review 56(3), 695–722.

- Brink, A, 1997. The marketing perception of grocery store retailers belonging to black business associations in Gauteng. Univeristy of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Chowdhury, M & Alam, Z, 2017. Factors affecting access to finance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) of Bangladesh. USV Annals of Economics and Public Administration 2(26), 55.

- Coase, RH, 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica 4(16), 386–405.

- Cresswell, JW, 2014. Research design, qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 6th ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Ebony Development Alternatives, 1995. Growth and linkage of South African SMMEs. Unpublished report prepared for the Black Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Support Facility, Johannesburg.

- GCRO, 2015. Quality of life survey IV (2015): Health. GCRO data brief No. 9. December 2018.

- GCRO, 2017. Gauteng quality of life survey: Data world. gcro-qols-2015-2016-technical-report.pdf.

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), 2014. The crossroads – A goldmine or a time bomb? Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Cape Town.

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), 2015. September 2015, GEM. http://www.gemconsortium.org.

- Gibrat, R, 1931. Les Inégalités économiques. Librairie du Recueil Sirey, Paris.

- Gillani, DQ & Khan, REA, 2013. Socio-economic determinants of urban informal sector employment: A case study of district Bahawalpur. Pakistan Perspectives 18(2), 133.

- Gujarati, D, 2011. Econometrics by example. Macmillan, London.

- Islam, MA, Khan, MA, Obaidullah, AZM & Alam, MS, 2011. Effect of entrepreneur and firm characteristics on the business success of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management 6(3), 289.

- Iyer, R & Schoar, A, 2008. Are there cultural determinants of entrepreneurship? Some NBER paper.

- Kamitewoko, E, 2013. The determinant for choice of economic activities performed by Chinese migrants in Congo. Research paper of Center of Research and Prospective Studies.

- Jovanovic, B, 1982. Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica 50(3), 649–70.

- Maduku, H & Kaseeram, I, 2019. Mainstreaming willingness among black owned informal SMMEs in South Africa. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences 10(3), 140–7.

- McPherson, MA, 1996. Growth of micro and small enterprises in Southern Africa. Journal of Development Economics 48, 253–77.

- Mead, DC & Liedholm, C, 1998. The dynamics of micro and small enterprises in developing countries. World Development 26(1), 61–74.

- Mokoena, SK, 2017. The role of Local Economic Development (LED): Some empirical findings on the Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (SMMEs). Journal of Public Administration 52(2), 466–79.

- Mueller, DC, 1972. A life cycle theory of the firm. The Journal of Industrial Economics 20(3), 199–219.

- Mukumba, T, 2014. Overcoming SMEs challenges through critical success factors: A case of SMEs in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Economic & Business Review 16(1), 19–38.

- Mwirigi, C, Gakure, RW & Otieno, RO, 2019. Collateral on strategic access to credit facilities by women owned small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 6(1), 285–92.

- Ndayizigamiye, P & Khoase, RG, 2020. Analysing the relationship between SMME geographic coverage and e-commerce adoption. In Perspectives on ICT4D and socio-economic growth opportunities in developing countries. IGI Global, Hershey, Pennsylvania. 212–23.

- Neves, D, Samson, M, van Niekerk, I, Hlatshwayo, S & du Toit, A, 2009. The use and effectiveness of social grants in South Africa Research Report Johanneburg FinMark Trust.

- O’Farrell, PN & Hitchens, DMWN, 1988. Alternative theories of small-firm growth: A critical review. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 20(10), 1365–83.

- Penrose, E, 1959. The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- Phelps, NA & Wijaya, HB, 2020. Growth and growth constraints in craft industry clusters: The batik industries of Central Java. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 41(2), 248–268.

- Powers, DA & Xie, Y, 2008. Statistical methods for categorical data analysis. Academic Press, San Diego.

- Rocha, EAG, 2012. The impact of business environment on the size of the micro, small and medium enterprises sector: Preliminary findings from a cross-country comparison. Procedia Economics and Finance 4, 335–49.

- Rogerson, CM, 2000. Developing small firms in township tourism: Emerging tour operators in Gauteng, South Africa.

- Santarelli, E & Tran, HT, 2013. The interplay of human and social capital in shaping entrepreneurial performance: The case of Vietnam. Small Business Economics 40, 435–58. doi:10.1007/s11187-012-9427-y.

- Sawaya, A, 1995. Black manufacturing small and medium-sized enterprises in the Western Cape: An analysis of success factors. Unpublished M.Com Dissertation, University of Cape Town.

- SEDA, 2015. The small, medium and micro enterprise sector of South Africa - Research Note 2016 | No 1. Small Enterprise Development Agency, Pretoria.

- Sefiani, Y, 2013. Factors for success in SMEs: A perspective from Tangier. Doctoral dissertation, University of Gloucestershire.

- Shibia, AG & Barako, DG, 2017. Determinants of micro and small enterprises growth in Kenya. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 24(1), 105–18.

- Statistics South Africa, 2015a. Quarter 2. Quarterly labour force survey, Pretoria, viewed n.d. http://www.statssa.gov.za/default.asp.

- Statistics South African, 2015b. The statistics bulletin. Pretoria, South Africa. http://www.statsa.co.za.

- Stattrekcom, 2016. Survey Sampling Methods. [weblog]. 5 March 2016. http://stattrek.com/survey-research/sampling-methods.aspx?Tutorial=AP.

- Stepanyan, GG, 2012. Revisiting firm life cycle theory for new directions in finance. SSRN 2126479.

- Visser, K, 1997. Enterprise education in South Africa. Papers on education, training and enterprise, no. 8, Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh.

- West, J & Bogers, M, 2014. Leveraging external sources of innovation: A review of research on open innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management 31(4), 814–31.

- World Bank, 2016. Doing business 2016: Measuring regulatory quality and efficiency. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- World Bank, 1993. Characteristics of and constraints facing black businesses in South Africa: Survey results. Unpublished paper presented at the seminar on The Development of Small and Medium Business Enterprises in Economically Disadvantaged Sections of the South African Communities, Johannesburg 1–2 June.

- World Bank, 2014. Economics of South African Townships: Special Focus on Diepsloot. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Yadav, IS, Pahi, D & Goyari, P, 2020. The size and growth of firms: new evidence on law of proportionate effect from Asia. Journal of Asia Business Studies 14 (1), 91–108.