ABSTRACT

The notions of foreign-owned small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have gained the attention of scholars in the SME literature due to the contributions that they make in both their home and host countries. Despite the growing attention on foreign-owned SMEs in the academic literature, there is limited literature exploring the motivations and unique challenges that these enterprises face in the various African contexts. This study, therefore, used the grounded theory approach on a sample of forty-two (42) owners of successful foreign-owned SMEs operating in South Africa to explore their motivations and unique challenges. Eight (8) categories of motivations and five (5) unique challenges for successful foreign-owned SMEs to start businesses in South Africa were identified. A grounded theory in this study shows the motivations for starting SMEs, dealing with unique challenges and success factors of foreign-owned SMEs. The study provides useful insights into the motivations of foreign-owned SMEs, as well as on how successful foreign-owned SMEs deal with unique challenges to succeed.

1. Introduction

Foreign-owned SMEs have been noted to make significant contributions in developed nations. Elo & Hieta (Citation2017) observed that strong economies, for example, the United States of America, rely on foreign-owned resources such as labour and entrepreneurs. Thus, understanding the notions of successful foreign-owned SMEs is of paramount importance for the economic progress of nations, especially in developing nations such as South Africa. The economic process of nations includes reduced unemployment, reduced poverty, reduced inequality and increased economic growth (Schumacher, Citation2016). Extant literature on SME development in South Africa has been centred on locally owned SMEs and seldom mentions successful foreign-owned SMEs which, in addition to the problems facing local SME owners, experience further challenges (Charman & Piper, Citation2012). Similarly, the specific motivations enabling successful foreign-owned SMEs to conduct business in South Africa remain unclear. Nevertheless, the past decade has seen the introduction of discussion on the notions of foreign-owned SMEs in the SME literature and other discussions in South Africa (Charman & Piper, Citation2012; Charman et al., Citation2012; Tengeh, Citation2013; Grant & Thompson, Citation2015; Rogerson, Citation2015; Ndoro, Citation2016).

Foreign-owned SMEs gained attention in South African SME literature following the media exposure of targeted attacks on foreign-owned businesses during the year 2008 (Crush, Citation2008), the dire effects of which were mostly felt by foreign-owned SMEs (Charman & Piper, Citation2012). Following this event, several publications relating to foreign-owned SMEs have produced mixed results. For example, in their study of foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa, Charman et al. (Citation2012) observed that some locally owned businesses were forced to close due to their failure to cope with the competition presented by foreign-owned SMEs. Nestorowicz (Citation2011) noted that the success of foreign-owned businesses is attributed to their networking and competitive intelligence. This fact may serve to suggest that successful foreign-owned businesses might have a competitive advantage over locally owned businesses and, thus, may present a cause for tension between locally owned and foreign-owned firms. Despite the mixed results of research conducted on the role of foreign-owned businesses in South Africa (Charman & Piper, Citation2012), the potential of foreign-owned businesses in closing the skills gaps, on cross-cultural knowledge diffusion and knowledge transfer, are some of the issues to be considered when viewing the notions of successful foreign-owned businesses (Rogerson, Citation2015). Ndoro (Citation2016) observed that foreign-owned businesses have been noted to be more innovative in their operations, thus explaining the growing influx of successful foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa.

While studies (Charman & Piper, Citation2012; Tengeh, Citation2013; Ndoro, Citation2016) have attested to the growing influx of foreign-owned SMEs into South Africa, it remains unclear as to the specific motivations of foreign-owned SMEs for starting businesses in South Africa. Also, there are a few studies (see Akinyemi & Adejumo, Citation2017; Shangase, Citation2017) that investigated the unique challenges experienced by foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa. In light of this previous research, the study at hand sought to investigate the motivations and the unique challenges of foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa. Its ultimate aim is to produce a substantive grounded theory that explains the motivations of successful foreign-owned SMEs, as well as how these businesses overcome these unique challenges and succeed.

The following section highlights the theoretical perspectives on motivations and challenges faced by successful foreign-owned SMEs. This segment will be followed by an explanation of the research methodology employed in this study. The findings of this study and the emergent ground theory are then presented. The study then offers discussions on the topic and, finally, provides the paper’s conclusions.

2. Theoretical perspectives on motivations and challenges of successful foreign-owned SMEs

Several theoretical perspectives may be used as a basis to explain the notions of motivations and challenges of successful foreign-owned SMEs. These theoretical perspectives can be drawn from theories such as the Uppsala Internationalisation Process Model (Johanson & Vahlne Citation1977; Zohari, Citation2008), immigrant entrepreneurship theories (Blanding, Citation2016; Chrysostome & Nkongolo-Bakenda, Citation2019), push-and-pull factor theories (Nieman & Nieuwenhuizen, Citation2018; Pan, Citation2019) as well as ethnic enclaves (Zhang & Xie, Citation2016) which are briefly introduced below.

One of the theories that explain the migration of business from one international location to another is the Uppsala Internationalisation Process Model (Johanson & Vahlne, Citation1977). Grounded on inductive studies of Swedish multinational entities, the Uppsala Model of Internationalisation is a behavioural-oriented theory that demonstrates the incremental manner through which businesses internationalise by focusing on market knowledge, market commitment, uncertainties, and resources (Zohari, Citation2008). This theory has been applied to the creation of international new ventures (foreign-owned SMEs) (Verbeke et al., Citation2014) in which the individual-level characteristics of entrepreneurs were found to be the driving motivations to start new international ventures. These motivations are related to the accumulation of requisite resources (Verbeke et al., Citation2014). The research literature on immigrant entrepreneurship also confirms that the characteristics of individual entrepreneurs, such as the experience of conducting business in other countries, knowledge of new markets and network relationships, influence their motivation to start new businesses in international markets (Vissak & Zhang, Citation2014).

Another possible theoretical explanation regarding the motivations of foreign-owned SMEs is based on the Push–Pull Factor theory, (Nieman & Nieuwenhuizen, Citation2018; Lok et al., Citation2019; Pan, Citation2019). This theory, which relates to motivational factors that encourage entrepreneurship due to traditional occupations being less attractive (‘push’ factors) and motivational factors that encourage people in conventional occupations to leave their current occupations to become entrepreneurs (‘pull’ factors) (Nieman & Nieuwenhuizen, Citation2018), has been studied in different contexts. For example, Lok et al. (Citation2019) determined the motivational forces that influenced the entrepreneurial efforts of female entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Other studies investigating the motivational factors for entrepreneurship were conducted in the United States of America (Kogan et al., Citation2018) and Brazil (Pereira & Gosling, Citation2019), however, no studies could be found in the reviewed literature to explain the factors that motivate successful entrepreneurs specifically within the African and South African contexts.

The Ethnic Enclave theory has been used to explain the motivations and how successful foreign-owned SMEs overcome the challenges they face (Zhang & Xie, Citation2016; Elo & Hieta, Citation2017; Kane et al., Citation2018). The Ethnic Enclave theory explains the concentration of certain foreign ethnic groups in specific locations in their host countries (Zhang & Xie, Citation2016). Elo & Hieta (Citation2017) observed that foreign nationals in ethnic enclaves support each other in starting new businesses and have unique ways in which they approach business opportunities and create their new enterprises. However, the specific approaches to business opportunities, the challenges experienced by successful foreign-owned SMEs, as well as their motivations for starting new businesses, remain unclear, especially in the South African context.

While existing theoretical perspectives provide glimpses of the possible motivations and unique characteristics (such as challenges) of foreign-owned SMEs, these existing theories are unable entirely to explain in the internationalisation experiences of foreign-owned SMEs (Cruz et al., Citation2016; Emontspool & Servais, Citation2019). Previously researchers such as Shangase (Citation2017) and Akinyemi & Adejumo (Citation2017) have included in their studies the motives and challenges facing foreign-owned SMEs attempting to start businesses in South Africa. These studies have alluded to challenges facing all SMEs, such as access to both finance and markets, bureaucracy and crime, among others, without singling out the unique challenges confronting successful foreign-owned SMEs. One of the challenges, that became apparent in the South African context as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic economic lockdown, is the lack of government support for foreign-owned SMEs (Moise et al., Citation2020). Only locally owned SMEs received targeted support while foreign-owned SMEs were left to fend for themselves. This situation exists despite the notable contributions made by successful foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa. For example, Khosa & Kalitanyi (Citation2014) noted that there are several foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa that make contributions in terms of employment creation, micro foreign-direct investment, and augment the growth of the local economy (Moise et al., Citation2020). Khosa & Khalatinyi (Citation2014) also reported that foreign-owned SMEs operate in diverse contexts, some of which are not well-documented in the reviewed literature, hence it is difficult to quantify their unique contributions.

The diversity of contexts from which foreign-owned SMEs emerge provides a challenge to researchers when trying to understand the motivations and unique challenges experienced by successful foreign-owned SMEs. Consequently, this study sought to explore both the motivations and unique challenges faced by thriving foreign-owned SMEs in the South African context. The methods applied in this study are described in the next section.

3. Research methodology

This paper applied the Grounded Theory approach of Strauss & Corbin (Citation1998), to explore the motivations and unique challenges experienced by successful foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa. This particular approach involves developing a substantive grounded theory based on data that was systematically gathered and analysed via a research process (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). The study is premised, therefore, on the phenomenological strand of the interpretivism research paradigm, which involves understanding a social reality from the perspective of the participants’ lived experiences (Bertram & Christiansen, Citation2018). Thus, in-depth interviews were conducted with a sample of forty-two (42) proprietors of successful foreign-owned SME.

The initial sample participants were obtained using purposive sampling methods. Purposive sampling involves selecting possible information-rich participants based on their possession of certain characteristics that are of interest to the researcher (Patton, Citation2015). In this study, successful foreign-owned SMEs were defined as established businesses that have been operating for more than three and a half years (Herrington & Kew, Citation2016). The success of the business was also determined in terms of business performance, profitability, return on investments, market share, number of employees as well as number of product lines (Radipere & Dhliwayo, Citation2014). It should be noted that although all of these factors were recognised as determinants of the success of the business, they were not established before the interviews. Thus, the primary determinant of success that was considered in this study is the period of operation, which was identified as the businesses having operated for more than three and half years. Businesses that did not meet the minimum number of operational years were excluded from this study. Thus, all foreign-owned SMEs that were interviewed for this study were deemed to be successful based on the stated definition of SME success used in this study, namely the criterion of having operated for at least three and a half years.

Subsequent samples were obtained using snowball sampling coupled with theoretical sampling through which emerging theoretical considerations guided the selection of further research participants. To complete this practice, concurrent data collection and analysis was conducted, meaning that data was collected, analysed and the emergent concepts tracked simultaneously.

Concurrent data collection and data analysis continued until theoretical saturation was achieved. Theoretical saturation relates to the point when emerging concepts have been fully explored and no new theoretical insights are being generated (Charmaz, Citation2014). Throughout the whole process, constant comparison of emerging concepts was conducted to maintain a close connection between concepts and categories. This comparison was achieved through data management and coding using NVIVO 12 software.

To prove rigour and ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, due care was taken to ensure that the findings reflected the reality and lived experiences of the participants. To achieve this legitmacy, member reflections (Tracy & Hinrichs, Citation2017) in which participants were allowed to read the interview transcripts, as well as to comment on the analysed data, were used. In all instances, participants confirmed that the findings were a true representation of their lived experiences in running successful foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa. The following section presents the findings of this study.

4. Findings

The findings of this study cover the motivations of successful foreign-owned SME owners for starting businesses in South Africa, as well as the unique challenges that successful foreign-owned SMEs experience in South Africa. These findings are grounded on empirical data obtained through in-depth interviews with forty-two (42) owners of successful foreign-owned SMEs. The study aimed to gain an understanding of the motivations and challenges facing these businesses. Firstly, Section 4.1 provides an overview of the study participants, followed by a discussion of the motivations and challenges facing successful foreign-owned SMEs in Sections 4.2 and 4.3, respectively. A grounded theory on these motivations and challenges is then presented in Section 5.

4.1. Overview of participants

As shown in , a total of 42 participants were engaged in this study. These participants consisted of successful SME owners/managers from various countries who were conducting business in the Gauteng and Limpopo provinces of South Africa. Data collection took place between the period August 2018 to December 2018.

Table 1. Overview of participants.

Participants came from eleven (11) different countries. The largest number of participants originated from Zimbabwe (14), followed by Nigeria (7), Zambia (6) and Ghana (3). Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India and Pakistan were represented by 2 participants each, while one (1) participant came from Portugal. One participant (the owner) from each SME was interviewed. Thirty-two (32) of the participants were males and ten (10) were females. The following section presents the findings regarding their motivations for starting businesses in South Africa.

4.2. Motivations for starting a business in South Africa

Relevant words, phrases, statements, or observations were extracted from each participant’s transcript to identify their specific motivation for starting a SME in South Africa. The results of the initial coding process are shown in . The codes presented in were identified from portions of the data, the process of breaking down the data, as well as the memos written by the researcher during and after the interviews.

Table 2. Motivations for starting business in South Africa.

By comparing and analysing the inter-relationships between the initial codes, the codes were reassembled into more abstract categories using axial coding techniques. The axial coding yielded eight categories of motivations for starting new businesses in South Africa. These motivations were grouped into (i) personal factors, (ii) influence of others, (iii) exclusion from the mainstream economy, (iv) discoveries, (v) favourable conditions in the host country, (vi) unfavourable conditions in the home country, (vii) community factors and (viii) financial factors. All the initial codes identified in the data fitted into these categories and this coding process became the basis of concept development. The categories and their respective coding concepts are shown in . The numbers of participants who mentioned at least one or more of the identified concepts per category are also shown in the References column of .

Table 3. Results of axial coding on motivations to start SMEs in South Africa.

Each of the categories will be discussed in the following subsections.

4.2.1. Personal factors

Personal factors were strongly expressed by forty-two (42) foreign-owned SME owners as their main motivations for starting SMEs in South Africa. Personal factors included passion and drive, the desire for self-employment, vision, interests and hobbies, personal values, previous work experience, desire to grow, experience from the home country, education, flexibility, skills possessed, background knowledge, personal experiences, desire to use skills and putting yourself to work.

The participants pointed out that passion and drive were their main motivation for starting specific business ventures in South Africa. These sentiments were strongly stressed by Participant 11 who, when asked about why she started a restaurant, replied as follows: ‘Actually, I like cooking a lot.’ The emphasis in Participant 11’s voice showed her passion for what she does. While sitting in her restaurant, waiting to interview Participant 11, the researchers wrote the following memo:

As I wait, I could see through the corner of the counter, how the participant is preparing meals for her clients with love and passion for her job. The passion and love for what she was doing could be seen through her smiles and the tone of her voice as she instructs her other two staff members to come and collect the cooked food to serve customers. (Memo dated 12 August 2018, Gauteng)

Participant 36, who owns a fashion design shop, also noted that ‘right from when I was born … it’s the love I have for this designing that makes me go into it’. Participants 6, 14, 26 and 29, also expressed similar views.

Other personal factors include previous work experience, running a similar business in their home country and skills and education, all of which were major driving forces that led the participants to start SMEs in South Africa. For example, Participant 1 indicated that ‘having a legal background, having assisted quite a good number of clients on how to start-up companies’ was the main reason why he started his legal consultancy business. Participant 13 also affirmed that his experience from his home country was the main reason why he decided to start a clothing business in South Africa. He commented: ‘ … when I was back home I was into clothing business’. These comments are an indication that some participants used experiences and skills obtained from their home countries to start successful businesses in South Africa.

Other codes relating to personal factors included background knowledge about the business, experience in a similar line of business obtained from home countries, the desire to utilise the skills they possessed, and the need for independence (self-employment) and flexibility. The interrelationship among these and other factors play a major role in the establishment of successful foreign-owned SMEs.

4.2.2. Influence by others

Another category motivation involved the influence of others. Participants indicated that it was not initially their intention to start their own business but they were influenced by others who saw potential in their operations. Participant 20 indicated that ‘it was an individual that I worked with on a project [who encouraged me to start the business]. My first project was dissolving an estate. So, I found it very interesting and the guy just said, “By the way, let’s start a business”’. The influence of others also includes family members who encouraged the participants to start their businesses. Participant 6 pointed out that ‘my fiancé motivated me to start the business’. The same sentiments were echoed by Participant 41 whose wife encouraged him to join her in business. The role of family and others in motivating foreign-owned SME owners to start SMEs in South Africa was further confirmed by Participants 4, 6, 11, 15, 20, 23 and 31. The family background in which individuals were raised to have ‘business savvy’, influenced successful foreign-owned SME owners to start their businesses.

4.2.3. Exclusion from the mainstream economy

Exclusion from the mainstream economy such as education and job opportunities were cited among the motivations for starting SMEs in South Africa. Nine participants indicated that lack of job opportunities and/or loss of employment was one of the key reasons why they were motivated to start their own SMEs to earn a living. Even when they acquired employment, they indicated that they were often paid low wages in contract work and this situation encouraged them to start their own businesses. Participant 27 mentioned: ‘I got retrenched then I started working, I started doing my stuff.’ Therefore, lack of job opportunities, loss of employment or unattractive employment opportunities were among the motivations for starting SMEs for foreign nationals in South Africa.

4.2.4. Discoveries

Discoveries were cited as one of the main motivations for starting SMEs in South Africa. Participants indicated that they had discovered an unserved market, new opportunities or new products. Most participants (16) indicated that they ‘saw a gap in the market’. Participant 19, who runs a consulting firm, indicated that ‘the government cannot handle certain things’, hence he and his partners were motivated to start a consultancy that targets government departments. Similarly, Participant 22, who operates a general merchandise store in a rural township in Limpopo, indicated that he was motivated by the ‘existence of marginalised markets in the rural communities, unserved markets’. This was confirmed by the following researcher’s memo:

There is only one general merchandise shop in this township. The other outlet that is there is a tavern which sells alcohol and cigarettes only. There are, however, two other recently established spaza shops nearby, both owned by other Somalis. These Somali-owned spaza shops had very limited stock. The Somalis who owned the spaza shops declined to be interviewed but one of them mentioned that they buy their stock from the only general merchandise shop in the township and recommended that I interview the owner of the general merchandise instead. (Memo dated 13 September 2018, Limpopo)

Therefore, factors such as the opportunity to provide unique or affordable products had encouraged these successful foreign-owned SMEs proprietors to start their businesses. Thus, participants interviewed in this study identified opportunities and used their knowledge of such situations to enter into untapped/unserved markets.

4.2.5. Favourable conditions in the host country

Another motivating factor identified was related to favourable conditions for conducting business in South Africa. The sub-categories that emerged from this factor included ease of conducting business, favourable business environment, no bureaucracy, the presence of potential customers, market size, availability of resources, favourable legislation, usable market, ready market and South Africa’s position on the African continent. The motivations listed in this section are in contrast with the experiences of South African-owned SMEs who do not find the legislation or other conditions favourable for conducting a business (for example see, Asah et al., Citation2020). However, foreign-owned SMEs find the conditions in South Africa propitious because of the comparatively worse conditions in their home countries. For example, Participant 2 who is from Zimbabwe indicated that conditions for conducting business in South Africa were more positive than those in Zimbabwe. The same sentiments were echoed by other participants from countries such as Ethiopia, Somalia and Portugal. This particular motivation is related to the concept of unfavourable conditions in the home country discussed in the next section.

4.2.6. Unfavourable conditions in the home country

Participants also noted unfavourable conditions in their home countries as among the factors that led to them to starting SMEs in South Africa. These elements include political instability, civil wars and economic hardship. Thus, the more favourable conditions in South Africa made it easier for the migrants to establish businesses in this country than in their home countries.

In examining this factor, the following researcher’s memo is of relevance:

Factors relating to favourable conditions relate to push and pull factors as noted in Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen’s (Citation2018) book entitled Entrepreneurship: A South African Perspective. (Memo dated 15 January 2019, Gauteng)

Five (5) participants in this study expressed this factor. For example, participant 20 said,

We didn’t have a lot of challenges in South Africa. Portuguese people are very motivated because we came from a very poor country. You will always see that your poorer areas or your poorer countries, your Portuguese, your Italians from Sicily, your Greeks from Cyprus, your Indians, that type of stuff … the reason why they succeed is that they have come from very, very poor backgrounds. So they know what it is to suffer.

4.2.7. Community factors

An unexpected factor that emerged from the analysis relates to community factors. Some participants indicated that they were motivated by the desire to uplift the communities in which they live through social enterprises and pursuing social responsibility initiatives. One participant specified that they were driven by the desire to uplift or promote their own culture in the culturally diverse community of South Africa.

4.2.8. Financial factors

Financial factors also emerged as a driver of establishing a business in South Africa. Some participants mentioned that low salaries paid to foreign nationals by some companies drove them to start their own business. Although the financial motive was not explicitly expressed by most of the participants, there was clear evidence of its relationship to other identified factors. A constant comparative analysis using coding stripes on NVIVO 12 showed that this sub-category was related to exclusion from the mainstream economy. Other related factors included the desire to generate additional income, to earn a living as well as the financial rewards of entrepreneurship in South Africa.

Our analysis showed an interrelationship among the motivations of successful foreign-owned SMEs to start businesses in South Africa. We used constant comparative methods to show these interrelationships. The following section presents the results of these constant comparative methods.

4.2.9. Constant comparative method on motivations of successful foreign-owned SMEs

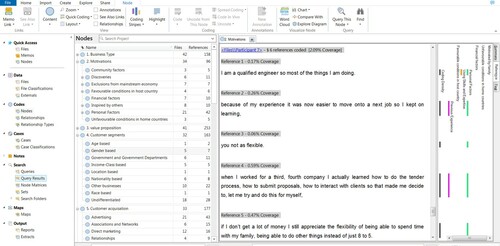

Using the constant comparative method on NVIVO 12, the coding stripes were examined to identify potential relationships between all other concepts on the motivation of foreign-owned SMEs. The constant comparative method involved comparing incidents of similar data applicable to each category and integrating categories and their respective properties (Glaser, Citation2005). To do this, the researcher used the coding stripes on NVIVO 12 to observe the interrelationships among concepts (See as an example).

In , the coding stripes are the coloured bars shown in the last column. These bars represent the content that was coded for each concept. The coding stripe parallel to each other indicates that similar content was coded for different categories, which indicates interrelationships among categories.

An examination of the coding stripes along the motivation node showed that interrelationships existed between all eight factors that encouraged the participants to establish SMEs in South Africa. The inter-relationships indicate that the eight factors affect or are related to each other. For example, an examination of the coding stripes revealed that the data coded on personal factors were also coded for financial factors. Thus, the coding stripes provided valuable information on the relationships between personal factors and financial factors. Similarly, the study found relationships between favourable conditions in the host country and unfavourable conditions in the home country. This situation is an indication that foreigners leave their countries due to adverse conditions and come to South Africa where there are better conditions for operating a successful business. Only the concept of community factors showed very limited interrelationships with other factors. This omission is mainly because this factor only emerged from five participants. Nevertheless, the concept emerged strongly amongst these participants and necessitated its conclusion in the analysis.

4.3. Managing unique challenges

Following a similar analysis procedure as in Section 4.2 above, relevant words, phrases, statements or observations were extracted from each participant’s transcript to identify the specific challenges facing successful foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa. The codes identified in the transcript were used to describe the challenges faced by successful foreign-owned SMEs. These codes are listed in . The investigation of the challenges facing successful foreign-owned SMEs revealed 18 key challenges, as shown in .

Table 4. Challenges facing foreign-owned SMEs.

Successful foreign-owned SMEs experienced similar challenges to all other SMEs in South Africa (see common challenges in ). The common challenges were expressed in a variety of studies outlined in the reviewed literature on SMEs in South Africa (for example Musara & Fatoki, Citation2011; Zondi, Citation2017; Moos & Sambo, Citation2018). By comparing common challenges identified in the reviewed literature and a list of challenges that we pinpointed from our study, we found out that certain challenges were unique to foreign-owned SMEs (see unique challenges in ), namely cultural differences, discrimination and stereotypes, documentation or immigration problems, the language barriers and community resistance. These problems are discussed in the following sub-sections.

4.3.1. Cultural differences

In terms of cultural differences, the foreign-owned SMEs were more susceptible to this challenge due to their background, which was different from the South African context in which they operated. It also took these businesses longer to adjust to the cultural dynamics of South Africa before they could fully settle down and offer their products. The participants also indicated that they experienced challenges in trying to assimilate with local cultures, which are complex and diverse. For example, Participant 20 indicated that ‘ … South Africa has very diverse cultures and languages … each time I move my business to another province or even a certain town within the same province … I struggle to adjust’.

To deal with these challenges, successful foreign-owned SME owners indicated that they work closely with the community to assimilate local cultures and traditions. This adjustment includes participation in local cultural and other related events such as attending wedding ceremonies, attending and contributing towards funeral services in the community, sponsoring and participating at local social events (e.g. football matches and other social clubs). For example, Participant 24 said: ‘ … I sponsor many soccer teams in the area so we are very much involved … we advertise and we put ourselves out there. So people know about us – we’re in your face all the time’.

Through these practices successful foreign-owned SMEs present themselves as part of the communities in which they operate, leading to trust and mutually beneficial relationships.

4.3.2. Discrimination and stereotypes

Related to cultural differences, the SMEs indicated that they experienced high levels of discrimination and stereotyping. This adverse behaviour occurred at both the individual and institutional levels. At the individual level, the participants indicated that certain customers were not willing to conduct business with them because of their nationality. For example, Participant 19 indicated that this individual-level discrimination ‘can be linked to the issue of xenophobia’. Furthermore, participants indicated that some of the discrimination and stereotyping arised because of past negative experiences with other foreign-owned SMEs. For example, Participant 30 indicated that:

There are a lot of fly-by-night businesses and it’s normally associated with foreigners. [Locals would say] so and so did business and the following day the person disappeared or they [took] a deposit from the client, then the following day they go to Zim or Mozambique. So, that negative image is associated with foreigners …

At the institutional level, policies such as the BEE policies and Preferential Procurement Policies implemented by the South African government were seen as discriminatory towards foreign business owners. Because of these practices, the SMEs struggled to gain access to certain opportunities. Participant 3 strongly expressed the discriminatory effect of BEE as follows:

… this BEE started about 20 … I don't remember when exactly but that when they started saying we want to do business with South Africans only. Therefore, we worked like that because there are different grades of BEE, so we worked like that and we were getting work. And then, they said they want South Africans born in South Africa, that's when we were burnt, our fingers were burnt now. And then, we resisted at first, and say we will get whatever they give us. But then we realised that, for us to survive, we need to have a South African in the business.

To deal with this challenge, proper integration and working with the South African community was seen as the best solution for solving this problem. Thus, participants expressed community acceptance as the panacea to discrimination and stereotypical challenges. Also, participants expressed the need to conduct business with utmost integrity to dispel some of the stereotypes formulated against certain groups of foreign nationals.

4.3.3. Documentation or immigration problems

Another unique challenge that the study participants raised was related to documentation and permits. The foreign SME owners revealed that they often experienced challenges in obtaining business permits, visas and other documentation that they required to operate their business legally. The challenge of accessing documentation and permits was exacerbated by corruption and bureaucracy. For example, Participant 4 noted that ‘ … when I came to this country I tried to get a working permit for maybe R10 000 but now if you're going for working permit they start from R30 000. Then on top of R30 000 that you are paying, is fake also’.

To an extent, participants indicated that the issues of documentation were beyond their control but still suggested the need to work closely with government officials to assist them in meeting their compliance requirements. In this regard, some participants indicated that fully complying with tax laws, business licensing laws, as well as immigration, was the only way they could easily navigate the documentation challenges.

4.3.4. Language barriers

The participants mentioned language barriers as a challenge inhibiting smooth interaction with local customers. An interesting observation was that owners of most successful foreign-owned SMEs were attempting to learn the native languages, while others had already acquired some basic proficiency in the local languages. For example, Participant 4 indicated that ‘As a foreign national doing business, there's a lot of challenges, it's not my country, there are challenges, now I can't speak the local language but I am trying to learn’. Also, employing native South Africans was used as a way to learn local languages as well as integrating within the local communities.

4.3.5. Community resistance

The business owners cited community resistance as another challenge that they experienced. This challenge is related to discrimination, stereotypes, and intolerance. Amid all these challenges, however, the successful foreign-owned SMEs employ survival mechanism as well as other support structures to keep their businesses afloat. To overcome this challenge, most owners of successful foreign-owned SMEs have worked on creating mutually beneficial relationships with the local people in the communities in which they operate. This practice includes offering employment opportunities to members of the local communities, offering favourable payment terms, participating in community social events (such as funerals, weddings, traditional ceremonies, etc) as well as maintaining friendly relationships with local communities. Participant 20 explained this phenomenon when he said,

… we take our brand and we push it into the community because it is not only about getting from the community. We need to give back so that is a “give and take”. If you don’t do that you are not going to get brand out there.

the most important thing is, you try and engage the community. … don’t isolate yourself from the community. Then you will find out that, ja, in case of those attacks some of them will stand up and defend your business.

Following an analysis of both the motivations of foreign-owned SMEs and how the owners of successful foreign-owned SMEs deal with unique challenges, we developed a grounded theory that explains these phenomena. The grounded theory is presented in the following section.

5. A grounded theory on motivations and unique challenges facing successful foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa

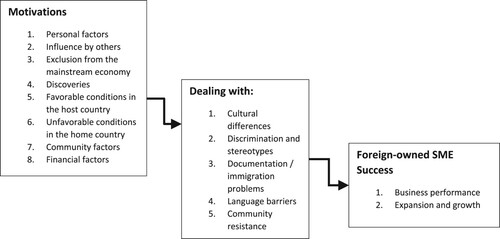

Our grounded theory (see ) hypothesises that successful foreign-owned SMEs can deal with their unique challenges driven by their motivations for starting their businesses. This practice will enhance the success of their businesses through increased business performance, expansions and growth opportunities.

Figure 2. A grounded theory on motivations and unique challenges of successful foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa.

Our grounded theory shows the interrelationships between motivations, dealing with unique challenges as well as foreign-owned SME success factors. The substantive grounded theory highlights the centrality of dealing with unique challenges to ensure the success of foreign-owned SMEs. An awareness of motivations, coupled with action steps to deal with unique challenges, are antecedents for foreign-owned SMEs’ success. This substantive grounded theory could be further explored using explanatory studies, as well as broader sample sizes from a variety of contexts, to strengthen the theorisation of how motivations and dealing with unique challenges of foreign-owned SMEs could be used to explain their success in host countries.

6. Discussions and conclusions

This study sought to explore the motivations of successful foreign-owned SMEs for starting businesses in South Africa. In addition, the unique challenges experienced by successful foreign-owned SMEs were also identified. A grounded theory developed specifically for this study explains how successful foreign-owned SMEs deal with the unique challenges that they face in order to achieve business success. Understanding the motivations and unique challenges facing successful foreign-owned SMEs is important in guiding endeavours to promote their growth to realise their full potential in as far as addressing unemployment, poverty and inequality.

Studies (for example Nestorowicz, Citation2011; Charman & Piper, Citation2012; Grant & Thompson, Citation2015; Ndoro, Citation2016) have shown that successful foreign-owned SMEs play a significant role in the economy of South Africa. For example, Nestorowicz (Citation2011) observed that successful foreign-owned SMEs possess superior knowledge, which enables them to succeed despite the hostile environment in which they operate. Moreover, strong economies such as the United States of America build strongly on migrant resources and foreign-owned SMEs (Elo & Hieta, Citation2017) and thus provide an impetus for other like-minded economies to consider endeavours to promote foreign-owned SMEs. Thus, understanding the notions of foreign-owned SMEs is important, not only for their development and for promotion, but also for the development of the broader SME sector in South Africa and abroad.

While general motivations for starting new businesses have been explored in the extant literature (for examples see Kogan et al., Citation2018; Lok et al., Citation2019; Pereira & Gosling, Citation2019), until now, the specific motivations of successful foreign-owned SMEs to start businesses in South Africa were rarely explored. Similarly, there are limited studies (for example see Shangase, Citation2017) that investigated the unique challenges facing foreign-owned SMEs in South Africa. Our study, therefore, closed these research gaps by offering new insights into the specific motivations and unique challenges facing successful foreign-owned SMEs starting businesses in South Africa. Developing insights into the motivations and unique challenges of successful foreign-owned SMEs is paramount to facilitate their full integration into the main economy and to realise their full potential. This process is important for the broader development of the SME sector, which is the backbone of many thriving economies not only in South Africa but also globally. Mainstreaming and systematisations of the SME sector development, therefore, should not be confined to local SMEs only, but also include foreign-owned SMEs from which useful insights and lessons for guiding business policy could be drawn. This study is not exhaustive, thus, we hope that it will act as a springboard to guide future studies that explore other aspects of foreign-owned SMEs in diverse contexts.

Disclosure statement

The findings in this paper were drawn from a broader PhD study entitled: Business Models of Successful Foreign-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises for Small Business Development in South Africa.

References

- Akinyemi, F & Adejumo, O, 2017. Entrepreneurial motives and challenges of SMEs owners in emerging economies: Nigeria & South Africa. Advances in Economics and Business 5(11), 624–33.

- Asah, FT, Louw, L & Williams, J, 2020. The availability of credit from the formal financial sector to small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences 13(1), 1–10.

- Bertram, C & Christiansen, I, 2018. Understanding research: An introduction to reading research. Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

- Blanding, M, 2016. One quarter of entrepreneurs in the United States are immigrants. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/one-quarter-of-entrepreneurs-in-the-united-states-are-immigrants. Accessed 15 July 2017.

- Charman, A, Petersen, LM & Piper, LE, 2012. From local survivalism to foreign entrepreneurship: The transformation of the spaza sector in Delft, Cape Town. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 78(1), 47–73.

- Charman, A & Piper, L, 2012. Xenophobia, criminality and violent entrepreneurship: Violence against Somali shopkeepers in Delft South, Cape Town, South Africa. South African Review of Sociology 43(3), 81–105.

- Charmaz, K, 2014. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Chrysostome, E & Nkongolo-Bakenda, JM, 2019. Diaspora and international business in the homeland: From impact of remittances to determinants of entrepreneurship and research agenda. In Elo, M & Minto-Coy, I (Eds.), Diaspora networks in international business, 17–39. Springer, Cham.

- Crush, J (Ed.), 2008. The perfect storm: The realities of xenophobia in South Africa. Southern African Migration Project. http://www.genocidewatch.org/images/South_Africa_09_03_30_the_perfect_storm.pdf Accessed 15 July 2017.

- Cruz, E, Barreto, C & Amaral, S, 2016. Analysis of the internationalization of Brazilian entrepreneurs in Orlando-USA according to the Uppsala model. In United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship. Conference Proceedings, CJ1. United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship.

- Elo, M & Hieta, H, 2017. From ethnic enclaves to transnational entrepreneurs: The American dream of the Finns in Oregon, USA. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 31(2), 204–26.

- Emontspool, J & Servais, P, 2019. Learning in various types of new ventures: The role of ‘incoming’ entrepreneurs. In Elo, M & Minto-Coy, I (Eds.), Diaspora networks in international business, 41–54. Springer, Cham.

- Glaser, BG, 2005. The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding. Sociology Press, Mill Valley, CA.

- Grant, R & Thompson, D, 2015. City on edge: Immigrant businesses and the right to urban space in inner-city Johannesburg. Urban Geography 36(2), 181–200.

- Herrington, M & Kew, P, 2016. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2016/2017. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 1–180.

- Johanson, J & Vahlne, JE, 1977. The internationalization process of the firm – a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign commitments. Journal of International Business Studies 8(1), 23–32.

- Kane, JB, Teitler, JO & Reichman, NE, 2018. Ethnic enclaves and birth outcomes of immigrants from India in a diverse US state. Social Science & Medicine 209, 67–75.

- Khosa, RM & Kalitanyi, V, 2014. Challenges in operating micro-enterprises by African foreign entrepreneurs in Cape Town, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(10), 205–15.

- Kogan, I, Graham, J, Belmont, Y & Bellenger, D, 2018. Russian-speaking immigrant motivation to become an entrepreneur in the US. SSRN Electronic Journal 2018, 1–26.

- Lok, SYP, Kumari, P & Sim, E, 2019. Push and pull factors for Malaysian women entrepreneurs within the urban based retail industry. Global Business and Management Research 11(2), 282–94.

- Moise, LL, Khoase, R & Ndayizigamiye, P, 2020. The influence of government support interventions on the growth of African foreign-owned SMMEs in South Africa. In Castaño-Martínez, MS (Ed.), Analyzing the relationship between innovation, value creation, and entrepreneurship, 104–24. IGI Global, Hershey.

- Moos, M & Sambo, W, 2018. An exploratory study of challenges faced by small automotive businesses in townships: The case of Garankuwa, South Africa. Journal of Contemporary Management 15(1), 467–94.

- Musara, M & Fatoki, O, 2011. The effectiveness of business development services providers (BDS) in improving access to debt finance by start-up SMEs in South Africa. International Journal of Economics and Finance 3(4), 208–16.

- Ndoro, TTR, 2016. Differentiating engagement of opportunity identification: A grounded theory study of Chinese immigrant entrepreneurs. Doctoral thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown.

- Nestorowicz, J, 2011. Know knowns and know unknowns of immigrant self-employment. Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw, Warsaw.

- Nieman, G & Nieuwenhuizen, C, 2018. Entrepreneurship: A South African perspective. 3rd edn. Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

- Pan, G, 2019. The push-pull theory and motivations of Jewish refugees. In Pan, G (Ed.), A study of Jewish refugees in China (1933–1945), 123–31. Springer, Singapore.

- Patton, MQ, 2015. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. 4th ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Pereira, GDA & Gosling, M, 2019. Push and pull motivations of Brazilian travel lovers. BBR. Brazilian Business Review 16(1), 63–86.

- Radipere, S & Dhliwayo, S, 2014. An analysis of local and immigrant entrepreneurs in South Africa’s SME sector. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(9), 189.

- Rogerson, CM, 2015. Progressive rhetoric, ambiguous policy pathways: Street trading in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. Local Economy 31(1), 1–15.

- Schumacher, R, 2016. Adam smith and the ‘rich country–poor country’ debate: Eighteenth-century views on economic progress and international trade. The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 23(5), 764–93.

- Shangase, NN, 2017. A comparative analysis of the critical success factors affecting local and foreign owned small-medium enterprises in the Ndwedwe area of Kwazulu-Natal. Doctoral dissertation.

- Strauss, A & Corbin, J, 1998. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Tengeh, RK, 2013. Advancing the case for the support and promotion of African immigrant-owned businesses in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4(2), 347–59.

- Tracy, SJ & Hinrichs, MM, 2017. Big tent criteria for qualitative quality. The international encyclopedia of communication research methods, 1–10.

- Verbeke, A, Amin Zargarzadeh, M & Osiyevskyy, O, 2014. Internalization theory, entrepreneurship and international new ventures. Multinational Business Review 22(3), 246–69.

- Vissak, T & Zhang, X, 2014. Chinese immigrant entrepreneurs’ involvement in internationalization and innovation: Three Canadian cases. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 12(2), 183–201.

- Zhang, C & Xie, Y, 2016. Ethnic enclaves revisited: Effects on earnings of migrant workers in China. Chinese Journal of Sociology 2(2), 214–34.

- Zohari, T, 2008. The Uppsala internationalization model and its limitation in the new era. International Management Strategy, Stockholm University School of Business.

- Zondi, WB, 2017. Challenges facing small business development in South Africa. Journal of Economic & Management Perspectives 11(2), 621–8.