ABSTRACT

The passing of the 2019 National Health Insurance Bill (NHI) has revived debate whether such a policy can be effectively implemented in South Africa. The purpose of this article is to discuss the development process of this bill against the backdrop of the country’s political and social context. Furthermore, it will examine the constitutional right of public participation in health policy decision-making and its vital role in understanding the user perspectives to ensure successful implementation of the NHI. Approachable and communicative leaders are required to facilitate public participation and to engage with the public and health workers. Such leaders will need to be innovative and creative in order to overcome current public health shortfalls.

1. Introduction

South Africa has a history of racial segregation and discrimination whereby the health system and its policies were used to reinforce white supremacy and capitalist ideals (Price, Citation1986). In 1994, the country became a democracy and the elected party, the African National Congress (ANC), developed a National Health Policy that aimed to overcome past injustices. The Constitution was created in 1996 and has since been the country’s supreme law, and all policies must be aligned with its standards (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Citation1996). The 1994 National Health Policy, as well as other health policies that have been implemented post-apartheid, have had mixed success (Giaimo, Citation2016).

Currently, South Africa’s health system consists of a private and a public sector. This duel structure has been criticised for its unequal nature whereby only the socio-economic elite utilises private healthcare, and the large majority of the population are left to rely on the under-resourced and overburdened public sector (Burger & Christian, Citation2018). In order to address the current disparities in healthcare, the ANC government has begun the process of implementing a National Health Insurance Policy (NHI) with the end goal of achieving affordable and accessible Universal Health Coverage (UHC). UHC is defined as the provision of affordable and high-quality health services for all people (World Health Organisation, Citation2019a).

A national health policy is essential in creating the circumstances that allow for an entire population to be of good health. There are three crucial elements of a national health policy. These include the political, social and cultural context, lifestyle considerations and empowering approaches (Navarro, Citation2007). The political and social context of South Africa is deeply intertwined with healthcare as it directly impacts individual safety, economic success and public involvement in politics (Arnold, Citation2020). This article will discuss the development and implementation of the NHI within the context of South Africa’s political and social history. Furthermore, public health financing, decision-making structures and public involvement will be considered. The government perspective on the country’s need for NHI will be revealed as well as the health worker and user perspectives.

2. Political and social context of National Health in South Africa

2.1. South Africa under apartheid rule

Apartheid, which means ‘aparthood’ when translated from Afrikaans, was introduced in 1948 by the governing political party, the National Party (NP). Apartheid entailed racial segregation in favour of the white minority population and was established on the foundation of European colonialism and the associated racial hierarchical ideals (Giaimo, Citation2016). Horwitz (Citation2009) states that apartheid was partly justified by the outbreaks of diseases, such as the bubonic plague, smallpox and Spanish influenza. These diseases added to already established misconceptions regarding the black population and their supposedly unhygienic character (Horwitz, Citation2009). Due to the perceived potential threat to white populations, policies were put in place to protect the health of the whites and to ensure racial segregation throughout the country (Land, Citation2003).

Policy decision-making and governance during apartheid involved top-down processes and was exclusive to the State Security Council, which involved only white members of the population (Geldenhuys & Kotzé, Citation1983). Health expenditure and resource allocation was based on racial hierarchy and, therefore, highly unequal and disproportional. Healthcare for the majority black population was disregarded, and millions of South Africans suffered (Harris et al., Citation2014). Price (Citation1986) argues that the segregated health systems during apartheid were used as a tool by the NP to reinforce their assumptions of white supremacy and to maintain capitalist ideals.

2.2. South Africa and democracy post-apartheid

From the 1950s onwards, apartheid led to conflict between the state and citizens, resulting in the formation of civil society liberation groups, such as political parties and labour organisations. These groups were often banned, leading to increased conflict between the public and government (Giaimo, Citation2016). Local and international pressure in February 1990 led to negotiations between the government and the leading democratic political party, the ANC. The formal processes leading towards a non-racial and participatory democracy for South Africa began in 1990 (South African Legislative Sector, Citation2013). Policies were created and implemented, such as the National Policy for Health Act 116 of 1990, whereby healthcare standards were re-evaluated to provide adequate healthcare for all South Africans, regardless of their race (van Rensburg, Citation2012). The first national democratic elections were held in 1994, and the ANC was voted into power. The ANC has continued to win every election since (Giaimo, Citation2016).

In order to rectify the injustices of the past, break down racial barriers, and create equality for all, a complete transformation of the health systems in South Africa was necessary (Giaimo, Citation2016). The ANC introduced the National Health Policy in May 1994, which focused not only on medical care but also on pursuing healthy lifestyles for all South Africans with the establishment of Primary Health Care (PHC) facilities (African National Congress, Citation1994). PHC, as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO), is essential in promoting health, protection and prevention, identifying further determinants of health and empowering communities (World Health Organisation, Citation2019b).

The Constitution, which includes the Bill of Rights, was established in 1996 and has since been the country’s supreme law. The Constitution lays the foundation for all present and future policies to be fair and in alignment with its standards (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Citation1996). The Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) is a lawful body that exists to ensure adequate regulation of health professionals and facilities (Health Professions Council of South Africa, Citation2020).

In 1997 the White Paper for the Transformation of Health Systems was published, followed by the National Health Act 61 of 2003, which has since been the country’s health policy (Hassim et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, the National Development Plan 2030, which contains governmental health, economic and environmental goals for 2030, was established in 2013 (van Rensburg, Citation2012). The ANC, through these policies, has made significant progress in moving South Africa forward, most notably by recognising that health care is a human right (Giaimo, Citation2016). The creation of the world’s most extensive antiretroviral treatment programme and the development of PHC facilities in rural areas are further successes of the ANC (African National Congress, Citation2019).

Since South Africa became a democracy, healthcare has been divided into the private and public sector, and government spending is equally divided between the two sectors (Rispel, Citation2016). The government has allocated 12%, approximately R248 billion, of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) towards healthcare (National Treasury, Citation2021). It is important to note that the private sector supports only 16% of the population, which is the socio-economic elite, and the remaining 84% rely on the overrun and poorly managed public sector (Burger & Christian, Citation2018). This imbalance has contributed to South Africa remaining one of the most unequal countries in the world (Harris et al., Citation2014). South Africa also faces challenges of high unemployment rates, pressure for economic growth and inadequate access to quality healthcare (Tshoose, Citation2015).

2.3. Shortfalls of health policies since 1994

Many inspiring policies have been introduced since South Africa became a democracy, however, due to poor implementation and lack of evaluation, they are not effectively being utilised (Gilson & McIntyre, Citation2007). Rispel (Citation2016) acknowledges three factors contributing to this inefficiency. Firstly, there has been a tolerance of unsatisfactory leadership, management and governance failures. Corruption has additionally contributed to mistrust of the government and inadequate health care funding (Rispel et al., Citation2015).

Secondly, there is a lack of fully functional PHC facilities (Rispel, Citation2016). There is an imbalance of health workers and funds, which will be discussed in more detail below, in the different provinces as well as private and public sectors. The public sector and the PHC facilities are overburdened and under-resourced (McIntyre et al., Citation2014). Currently, only 30% of health workers practice in the public sector while the remaining 70% are in private (Labonté et al., Citation2015) Furthermore, the public sector carries the heavy burden of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Multi-drug Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Costly transport, limited free time and a perceived loss of dignity are additional barriers for individuals in low-income households seeking health care at PHC facilities (Nkosi et al., Citation2007).

The inability of the government to resolve or improve the health worker shortage is the third factor in understanding the poor implementation of health care policies (Rispel, Citation2016). Low remuneration, high living costs, poor working conditions and lack of career advancement opportunities contribute to unmotivated, sometimes aggressive, staff (Rispel et al., Citation2015). The private sector is more appealing than the public due to the high employee value proposition where working conditions and remuneration are superior. There has also been a continual increase in health worker migration overseas (Labonté et al., Citation2015).

These factors contribute to perceived poor quality of care by South Africans (Nkosi et al., Citation2007). As demonstrated in Thailand, if health care is perceived as low quality, medical health insurance and out-of-pocket fees will rise (Passchier, Citation2017). The increased unaffordability of private health care results in the increase of poverty as well as the reinforcement of segregation (Mkhize, Citation2019). Eliminating barriers and improving the abovementioned factors are central aspects of the government’s perspective and motivation for implementing the NHI. Prior to critical analysis of the NHI policy, the South African decision-making process needs to be understood.

2.4. Funding public health services

Public healthcare funding is currently decentralised and is distributed both nationally and provincially. Public sector services are governed by individual provincial departments (Michel et al., Citation2020). Approximately 3.8% of South Africa’s GDP is allocated to provincial public spending by means of a need-based formula. Each province has executive control over its funds and distributes it accordingly to designated sectors, such as education, health and security (Michel et al., Citation2020). 76% of the country’s Total Health Expenditure is distributed to the nine provinces through unconditional provincial equitable shares (PES). The remaining 24% is allocated to the National Department of Health (DoH). The majority of these funds are then distributed to the provinces through conditional grants (UNICEF, Citation2020).

Healthcare receives 27% of the country’s PES transfers with factors, such as individual provincial risk characteristics and capacity of healthcare facilities, being considered (Roos, Citation2020). The South African government utilises PES to achieve fiscal equalisation of the provinces (Alm & Martinez-Vazquez, Citation2015). However, this goal has not been obtained due to notable differences in the distribution of financial and human resources among the provinces. Additionally, accountability in South Africa’s district health system, such as district committees or councils, are non-exist or are not actively involved in decision-making (Michel et al., Citation2020).

District health systems (DHS) and PHC facilities are a crucial component of a functioning health system in developing countries to promote equal and efficient healthcare (Fusheini & Eyles, Citation2016). The funding that PHC facilities currently receive is adjusted on an incremental basis in conjunction with an item-line budget. This process has prevented dynamic and active purchasing of resources and services (McIntyre e al., Citation2014). The inadequacy of the current DHS financing results in the inability of district managers to make effective decisions and the local health benefits of a decentralised health system not being recognised (Michel et al., Citation2020).

3. Policy decision-making in South Africa

3.1. Decision-making structures

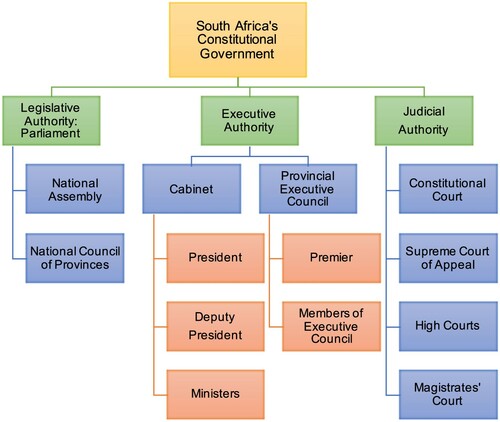

The South African government is designed as a non-discriminatory and unitary participatory democracy with a three-tiered system that involves an independent judiciary. It is solely responsible for constitutional policy creation and implementation (Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Citation2020). The three tiers are both independent and interconnected (South African Legislative Sector, Citation2013). demonstrates the three relevant tiers, namely the legislative, executive and judicial authorities, and their subparts.

Figure 1. South Africa’s Constitutional Government. Source: Author’s own development.

Note. Adapted from How Law is Made, by Parliament of Republic of South Africa, 2020. Copyright 2020 by Parliament of Republic of South Africa. Adapted with permission.

Bills are created by departments and presented to Cabinet for approval and then to Parliament for a final ruling (South African Government, Citation2020). In the case of the NHI, the bill was drafted in 2018 by the DoH and was put forward to Cabinet by the Minister of Health (Parliamentary Monitoring Group, Citation2019). The bill was approved by Cabinet and was introduced to Parliament in 2019. The National Assembly, the main decision-making body of Parliament, comprises of 400 members where the allocated seats are proportional to the number of votes cast per political party in the national elections (Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Citation2020). Currently, due to the ANC maintaining a large majority of these seats, they virtually rule as a single party government (Giaimo, Citation2016).

The decision-making process regarding national health is structured similarly to the government, whereby decisions are made via top-down processes (Alence, Citation2004). At the top of the hierarchy is the DoH, followed by nine provincial departments and, at the bottom, local and district health authorities (South African Government, Citation2020). The DoH is responsible for the policy creation and the allocation of funds and resources, the provincial departments represent the interests of each of the nine provinces, and the local and district levels ensure adequate operating of health facilities (Giaimo, Citation2016).

It can be argued that the decision-making processes in South African should, instead of top-down processes, rather involve bottom-up inputs to reflect a relationship web. A web would ensure that the voice of the public and those at the lower levels of the hierarchy are heard and considered (Harris et al., Citation2014). Houston (Citation2001) states that public participation in South African must be improved in order to abide by the Constitution and ensure that appropriate implementation of policies is achieved.

3.2. Public participation in decision-making

Public participation is the process whereby the government consults with the people prior to making decisions and creates a platform for two-way communication to occur. This ensures that the decisions made are agreeable and the associated goals will be reached with the public’s help (Tshoose, Citation2015). It is a necessary function of a modern participatory democracy and ensures that the public is involved in the decision-making, implementation and evaluation of policies. Participation is a constitutional right, and it warrants government accountability and transparency (Maphazi et al., Citation2013).

The public is encouraged to participate in decision-making through submissions directly to the government or to representative civil society bodies, attending conferences and workshops, and sharing in public hearings (Houston, Citation2001). The Public Participation Framework was published in 2013 by the South African Legislative Sector and is in place to express the importance of public involvement within the country’s democracy (South African Legislative Sector, Citation2013). Despite this framework, the government is currently lacking in its ability to involve the public in its decision-making.

Negligence, lack of service delivery, irregular feedback, inexperience of the officials and corruption are factors that need to be investigated and improved upon by leadership for public participation to be enhanced (Tshoose, Citation2015). Those living in poverty, which was more than half of the population in 2015, should be given a voice (Statistics South Africa, Citation2017). Tshoose (Citation2015) states that their voice isn’t heard due to the poor being seen as disorganised and often chaotic. The government, to rectify this, needs to address these status inequalities by using straightforward terms, publishing papers and hosting hearings in various languages and offering transport to these hearings (Amado et al., Citation2012). Not addressing these issues and not including all stakeholders on all levels in health care decision-making will result in resistance against the NHI and subsequent inadequate implementation (Passchier, Citation2017).

4. National health insurance policy

4.1. The need for NHI: the government perspective

The WHO recognises UHC as essential in providing adequate health care to the world’s population (World Health Organisation, Citation2019a). Countries like France, Thailand and the United Kingdom (UK) have had success in implementing UHC health systems (Child & Mashego, Citation2019). There is difficulty, however, in comparing UHC in these countries with African countries due to different demographic, economic, political and social factors (Crinson, Citation2009). African countries are uniquely challenged with high mortality rates, malnutrition, prevalence of chronic diseases and insufficient resources (World Health Organisation, Citation2016). The framework for UHC for Africa was published in 2016 by WHO. It highlights the benefits, both concerning the population’s health and economically, of moving forward with UHC despite these challenges (World Health Organisation, Citation2016). Ghana is an example of an African country that has adopted the UHC standards and has improved access to healthcare since its NHI scheme implementation in 2004 (Kipo-Sunyehzi et al., Citation2020).

Minister of Health, Dr Zweli Mkhize, challenged the attendees at the annual HPCSA conference to view the NHI as an opportunity for South Africa to achieve freedom from inequality, poverty and the injustices of the past (Mkhize, Citation2019). The 2019 NHI Policy states the goals of the NHI are improving access to quality healthcare for all South Africans, providing financial protection for individuals from health expenses and creating a public fund for all health services (National Health Insurance Bill, Citation2019). Implementing the NHI will improve the population’s health which results in an efficient workforce. A healthy and robust workforce with benefit South Africa economically (Amado et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, prioritising PHC will improve preventative medicine measures and reduce hospital stays and associated costs (Amado et al., Citation2012).

Successfully implementing UHC is significantly challenging for most countries, and no one best way or approach has been identified (Yamey & Evans, Citation2015). The South African government has chosen to implement NHI in incremental phases to rebuild trust with the public and to allow time for public health infrastructure and services to be improved (Mkhize, Citation2019). In Nigeria, it was made evident that the process of policy implementation was accelerated when well-known political leaders guide and support the process. A complete transformation of a health system cannot occur without political support (Onoka et al., Citation2015). Unfortunately, the DoH in South Africa has been unsuccessful in rallying public support for the NHI. Influential leaders are required that will generate both public and political support for NHI implementation (Onoka et al., Citation2015).

The National Health Service (NHS) in the UK was implemented after World War II and is considered one of the most successful UHC schemes in the world (Amado et al., Citation2012). It was implemented to reduce inequality and to create a unified national health system. At the time, similar to South Africa, the NHS was met with resistance and the impact on economic stability was observed (Amado et al., Citation2012). The South African government can learn from this and be prepared for opposition and challenges whilst maintaining the view that the NHI is a necessity.

4.2. Funding of the NHI

The purpose of the NHI will be to pool public revenue to create a NHI Fund based on social solidarity that will eliminate the division in health funding between the private and public sectors (National Health Insurance Bill, Citation2019). The policy also acknowledges the challenge of corruption and states that it is essential for adequate measures to be in place to ensure it does not continue (National Health Insurance Bill, Citation2019). Legislature regarding the NHI Fund and what health services it will cover has been vague and what is entailed is yet to be clarified (Child & Mashego, Citation2019). There is concern among the public as to how much tax they will be expected to pay and what structures of medical insurance will look like (Welthagen, Citation2019).

Despite showing a statistical increase in access to healthcare, the NHI scheme implemented in Ghana has not reduced inequality due to it being a voluntary and not a tax-based system. An annual premium is required by the users, making healthcare unaffordable for 60% of the population (Kipo-Sunyehzi et al., Citation2020). This scheme highlights the importance of South Africa implementing a tax-based NHI, despite its inconvenience to the public, to combat poverty and encourage unity. The government, however, is required to demonstrate greater transparency and clarity on public concerns.

The re-engineering and utilisation of PHC facilities are intended to be the foundation of the NHI in strengthening and restoring the DHS (Michel, et al., Citation2020). The values of DHS, which include autonomy, solidarity, equity and efficacy, are closely aligned with the values that underpin the proposed NHI (Fusheini & Eyles, Citation2016). WHO states that a fully functioning DHS with well-resourced and equipped PHC facilities are crucial in achieving UHC (World Health Organisation, Citation2019a). In accordance with these values, the government aims to alter public health financing by contracting private healthcare providers in the form of Contracting Units for Primary Health Care (CUPs). These CUPs will be integrated into PHC with the aim of promoting preventative and curative healthcare with rehabilitation services being made available to all South Africans (National Health Insurance Bill, Citation2019). Furthermore, the delegation of responsibilities in the DHS will be carried out by forming District Health Management Offices to ensure the public is served well at the local level (National Health Insurance Bill, Citation2019).

A high level of organisation and health service coordination is necessary to achieve the patient-centred, and decentralised NHI sought after by the government (Fusheini & Eyles, Citation2016). Consideration must be given to the time consuming and extensive processes that are involved in NHI implementation, such as the financial and management authority allocations in the DHS (Michel et al., Citation2020). The restructuring of public health financing in the implementation of the NHI will play a significant role in its success. However, if current and future challenges are not addressed at the district level, the goal of achieving the NHI by 2026 may be unobtainable (Michel et al., Citation2020).

4.3. Development and implementation of NHI

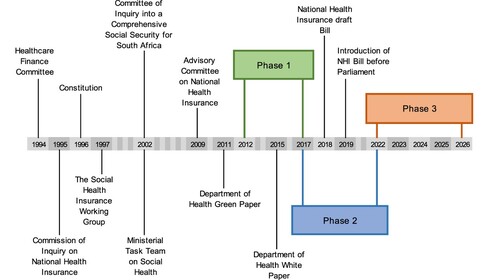

The aspiration for achieving UHC in South Africa has been a talking point for many years. In fact, 44 primary care centres were established pre-apartheid but were abolished when the NP came to power in 1948 (Giaimo, Citation2016). NHI was then mentioned in the 1994 ANC manifesto when running for election and in the subsequent National Health Plan once they were voted into power (African National Congress, Citation1994). Relevant committees and teams were established over time, as seen in , in order to reach the goal of developing an adequate NHI Policy (Parliamentary Monitoring Group, Citation2019).

Figure 2. Development of the NHI Bill in South Africa. Source: Author’s own development.

Note. Adapted from NHI Timeline: Key dates and events by Parliamentary Monitoring Group, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Parliamentary Monitoring Group. Adapted with permission.

NHI is structured to be implemented in three phases, as seen in , with the aim of all South Africans being covered by 2025/2026. Strengthening health services is an objective of all three phases (National Health Insurance Bill, Citation2019). The first phase involved piloting NHI structures at 10 PHC facilities. Evaluation of this phase demonstrated varying levels of success due to several challenges (Genesis Analytics, Citation2019). The challenges included a lack of planning, limited resources, inadequate communication and poor coordination and monitoring. Furthermore, there was little accountability for poor staff performance (Genesis Analytics, Citation2019). In cases where interventions were well designed, and managers led effectively, it was found that dedicated budgets did not support the policy objectives. This evaluation concluded that improvements are required in the governance of health systems to successfully implement NHI (Genesis Analytics, Citation2019).

Phase two is currently in progress and involves the development of legislature, namely the 2019 NHI Bill and the amendment of relevant existing legislation. The NHI Fund is to be created in this phase as well. The third phase involves reallocating resources as approved by Cabinet and establishing mandatory payment schemes (National Health Insurance Bill, Citation2019). A lack of clarity on practical steps required in each phase and inadequate communication from the government has contributed to confusion and negative public perceptions (Passchier, Citation2017).

4.4. Public participation with NHI: the user perspective

Public participation as seen throughout this article, is a central aspect of South African policies, however, the government has fallen short in providing adequate measures for the public to be involved in decision-making (Tshoose, Citation2015). South Africans have lost their trust in the government and, despite the government demonstrating the importance of implementing NHI, the public is uncertain of its capability to execute implementation successfully (Sekhejane, Citation2013). The health workers will be the driving force if NHI is to succeed, and their perspectives should be taken with careful consideration (McIntyre et al., Citation2009).

A survey was done in October 2019 by Solidarity Research Institute to determine health workers readiness, understanding, opinions and ability to adapt to the implementation of NHI (Welthagen, Citation2019). The results are based on 651 respondents from 3 different provinces. Almost 80% of the respondents had an unfavourable opinion or outlook on NHI. Apprehension regarding the government’s ability to make payments on time and manage staff shortages was recognised. Additionally, most respondents felt that the NHI could destabilise the healthcare system and satisfactory healthcare for the population is not feasible (Welthagen, Citation2019).

The results of this survey closely align with a report released by the Institute of Risk Management in South Africa, which reveals the risk the government is taking in implementing what they refer to as an ill-conceived, NHI policy (Institute of Risk Management, Citation2020). The report acknowledges that challenges such as the shortage of health workers, distrust in the health sector, inadequate service delivery, the government’s incapability to deal with corruption and the need for considerable capital funding may result in implementation failure (Institute of Risk Management, Citation2020).

A consensus among civil society groups, namely the Helen Suzman Foundation, Section27 and People’s Health Movement, is that the country is not ready for NHI as the current health system requires improvement first. This was made evident in their submissions made to the government in 2018 after the draft NHI Bill was published (National Health Insurance Library, Citation2018). A letter written in November 2018 by Ismail Momoniat, the acting director-general of the National Treasury, to the NHI presidential advisor, Dr O. Shisana, was leaked to the public. This letter expresses the National Treasury’s concerns with the 2018 bill and states that public and civil societal submissions have been disregarded (Momoniat, Citation2018).

The South African government’s justification for NHI is both understandable and admirable. Transformation of the health system is necessary due to poverty, increasing medical insurance fees and tolerance of inequality (Mkhize, Citation2019). However, policies and legislations are insufficient in themselves to battle inadequate management, ill-equipped facilities and underperforming institutions (Passchier, Citation2017). PHC facilities, which is to be the focus of NHI, require drastic improvements. Associated challenges, namely costly transport and loss of patient dignity, must be innovatively improved upon as well (Nkosi et al., Citation2007). Strengthening PHC will empower the public to take responsibility for their health and will contribute towards healthier lifestyles for the population as a whole.

The health workers and people of South Africa are considered the most valuable resource in ensuring acceptance and successful implementation of NHI (Yamey & Evans, Citation2015). The user perspective of the NHI is considerably negative, and the government must acknowledge this apprehension and reflect on it. It is recommended for a leader, such as the Minister of Health, to respond to stakeholder questions on a regular basis. NHI and the impact of its implementation should be explained, and public involvement should be facilitated and encouraged for all members of the population (Yamey & Evans, Citation2015). The complexity of facilitating public involvement has been seen in Nigeria, however, the implications of not yielding stakeholder support may result in continued inadequate access to quality healthcare for the population (Onoka et al., Citation2015).

4. Conclusion

Arising from South Africa’s history of racial discrimination and segregation, the polarisation of the national healthcare system manifested in enduring inequality. Historical policies that reinforced white supremacy ideals resulted in the unequal distribution of healthcare resources and poor public sector infrastructure (Price, Citation1986). Rectifying these past injustices is essential for the ANC, and post-apartheid policies have been aimed at achieving equality. Equality, however, has not yet been accomplished. The large majority of the population relies on the overburdened public sector, which is fraught with challenges of staff shortages, inefficient PHC facilities, inadequate management and corruption. Additionally, public involvement in decision-making has been overlooked. Top-down decision-making processes are currently in place, although bottom-up processes should be considered for the voice of the public and of health workers to be heard. Involving the public in current and future decision-making is both a constitutional requirement and an essential aspect of an authentic participatory democracy.

Implementing the NHI is perceived by the government as the only way forward in achieving UHC and equality in the health sector. The positive impact of UHC on a population’s health and the economy has been seen in many countries throughout the world. However, it is imperative that the South African government reveals greater transparency and clarity on public concerns and address current and future financial challenges in public health finance allocations. Policies are alone insufficient to battle inadequate management, ill-equipped facilities and underperforming institutions. The public and health workers will be the driving force for successful implementation. Assurances must be given specifically regarding the NHI Fund and its implications for the everyday user. Effective leaders who can engage with stakeholders regularly and who can reflect on their perspectives are needed. Furthermore, innovation is necessary for healthcare service delivery to overcome the current health system failures and to ensure adequate delivery of quality healthcare to all South Africans.

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) has put the NHI further into the spotlight in South Africa. The acute shortcomings of the PHC facilities will be evident. The pandemic offers a valuable opportunity to investigate the impact it will have on the health system and to conceptualise the implications for the implementation of the NHI.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- African National Congress, 1994. A National Health Plan for South Africa. https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/a_national_health_plan_for_south_africa.pdf.

- African National Congress, 2019. Let’s grow South Africa together: 2019 election manifesto. African National Congress, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Alence, R, 2004. South Africa after apartheid: The first decade. Journal of Democracy 15(3), 78–92.

- Alm, J & Martinez-Vazquez, J, 2015. Re-designing equalisation transfers: An application to South Africa’s provincial equitable share. The Journal of Developing Areas 49(1), 1–22.

- Amado, L, Christofides, N, Pieters, R & Rusch, J, 2012. National Health Insurance: A lofty ideal in need of cautious, planned implementation. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 5(1), 4–10.

- Arnold, K, 2020. The NHI could provide a dose of social justice for South Africa. https://mg.co.za/article/2020-03-15-the-nhi-could-provide-a-dose-of-social-justice-for-south-africa/.

- Burger, R & Christian, C, 2018. Access to health care in post-apartheid South Africa: availability, affordability, acceptability. Health Economics Policy and Law 15(1), 1–13.

- Child, K & Mashego, P, 2019. SA can learn about NHI from those who have it. https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/sunday-times-1107/20190908/282488595417654.

- Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Republic of South Africa. https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/SAConstitution-web-eng.pdf.

- Crinson, I, 2009. Health policy: A critical perspective. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, UK.

- Fusheini, A & Eyles, J, 2016. Achieving universal health coverage in South Africa through a district health system approach: Conflicting ideologies of health care provision. BMC Health Services Research 16(1), 1–11.

- Geldenhuys, D & Kotzé, H, 1983. Aspects of political decision-making in South Africa. Politikon 10(1), 33–45.

- Genesis Analytics, 2019. Evaluation of the phase 1 implementation of the interventions in the National Health Insurance pilot districts in South Africa. Republic of South Africa. https://www.hst.org.za/publications/NonHST%20Publications/nhi_evaluation_report_final_14%2007%202019.pdf.

- Giaimo, S, 2016. Reforming health care in the United States, Germany, and South Africa: comparative perspectives on health. Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK.

- Gilson, L & McIntyre, D, 2007. Are South Africa’s new health policies making a difference? Joint HEU/CHP policy brief. Health Economics Unit and Centre for Health Policy, Cape Town and Johannesburg. http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/4742.

- Harris, B, Eyles, J, Penn-Kekana, L, Fried, J, Nyathela, H, Thomas, L & Goudge, J, 2014. Bringing justice to unacceptable health care services? Street-level reflections from Urban South Africa. The International Journal of Transitional Justice 8, 141–61.

- Hassim, A, Heywood, M & Honermann, B, 2008. The National Health Act 61 of 2003: A guide. Siber Ink CC, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Health Professions Council of South Africa, 2020. About us. https://www.hpcsa.co.za/?contentId=463&actionName=About%20Us.

- Horwitz, S, 2009. Health and health care under Apartheid. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. https://www.wits.ac.za/media/migration/files/cs-38933-fix/migrated-pdf/pdfs-4/health%20and%20health%20care.pdf.

- Houston, G, 2001. Public participation in democratic governance in South Africa. HSRC Publishers, Pretoria.

- Institute of Risk Management, 2020. IRMSA risk report: South Africa risks 2020. https://files.irmsa-techlibrary.org.za/riskreport2020/.

- Kipo-Sunyehzi, DD, Ayanore, MA, Dzidzonu, DK & Yakubu, YA, 2020. Ghana’s journey towards universal health coverage: The role of the National Health Insurance scheme. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 10, 94–109.

- Labonté, R, Sanders, D, Thubelihle, M, Crush, J, Abel, C, Yoswa, D, Runnels, V, Packer, C, MacKenzie, A, Murphy, GT & Bourgeault, IL, 2015. Health worker migration from South Africa: Causes, consequences and policy responses. Human Resources for Health 13(92), 1–16.

- Land, G, 2003. “Healing the nation”: Medicolonial discourse and the state of emergency from apartheid to truth and reconciliation. Cultural Critique 54, 88–119.

- Maphazi, N, Raga, K, Taylor, JD & Mayekiso, T, 2013. Public participation: A South African local government perspective. African Journal of Public Affairs 6(2), 56–67.

- McIntyre, D, Doherty, J & Ataguba, J, 2014. Universal health coverage assessment. Global Network for Health Equity (GNHE), Cape Town, South Africa.

- McIntyre, D, Goudge, J, Harris, B, Nxumalo, N & Nkosi, M, 2009. Prerequisites for National Health Insurance in South Africa: Results of a national household survey. South African Medical Journal 99(10), 725–9.

- Michel, J, Tediosi, F, Egger, M, Barnighausen, T, McIntyre, D, Tanner, M & Evans, D, 2020. Universal health coverage financing in South Africa: Wishes vs reality. Journal of Global Health Reports 4, 1–12.

- Mkhize, Z, 2019. Opening address by Minister of Health. Presented at the Inaugural National Conference of the Health Professions Council of South Africa. South Africa.

- Momoniat, I, 2018. Revised National Health Insurance bill [Letter to Dr O. Shisana]. National Treasury of the Republic of South Africa. https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NHI-bill.pdf.

- National Health Insurance Library, 2018. Civil society submissions. https://www.nhilibrary.com/civil-society-1.

- National Health Insurance Bill, 2019. Government Gazette No. 42598. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201908/national-health-insurance-bill-b-11-2019.pdf.

- National Treasury, 2021. Budget 2021: Budget review. Republic of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Navarro, V, 2007. What is a national health policy? International Journal of Health Services 37(1), 1–14.

- Nkosi, M, Goudge, J & Kahn, K, 2007. Cost still a barrier to primary health care for rural poor in South Africa. Centre for Health Policy: Policy Brief 1.

- Onoka, CA, Hanson, K & Hanefeld, J, 2015. Towards universal coverage: A policy analysis of the development of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning 30, 1105–17.

- Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, 2020. How a law is made. https://www.parliament.gov.za/how-law-made.

- Parliamentary Monitoring Group, 2019. NHI timeline: Key dates and events. https://pmg.org.za/blog/NHI%20Timeline:%20Key%20dates%20and%20events.

- Passchier, RV, 2017. Exploring the barriers to implementing National Health Insurance in South Africa: The people’s perspective. South African Medical Journal 107, 836–8.

- Price, M, 1986. Health care as an instrument of Apartheid policy in South Africa. Health Policy and Planning 1, 158–70.

- Rispel, L, 2016. Analysing the progress and fault lines of health sector transformation in South Africa. South African Health Review 2016, 17–23. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC189322.

- Rispel, LC, de Jager, P & Fonn, S, 2015. Exploring corruption in the South African health sector. Health Policy and Planning 31, 239–49.

- Roos, EL, 2020. Provincial equitable share allocations in South Africa. The Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University, Australia. https://www.copsmodels.com/ftp/workpapr/g-298.pdf.

- Sekhejane, PR, 2013. South African National Health Insurance (NHI) policy: Prospects and challenges for its efficient implementation. Africa Institute of South Africa 102, 1–4.

- South African Government, 2020. Structure and functions of the South African Government. https://www.gov.za/about-government/government-system/structure-and-functions-south-african-government.

- South African Legislative Sector, 2013. Public participation framework for the South African legislative sector. http://www.sals.gov.za/docs/pubs/ppf.pdf.

- Statistics South Africa, 2017. Poverty trends in South Africa: An examination of absolute poverty between 2006 and 2015. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=10341.

- Tshoose, CI, 2015. Dynamics of public participation in local government: A South African perspective. African Journal of Public Affairs 8(2), 13–29.

- UNICEF, 2020. Health budget brief: South Africa 2019/20. UNICEF: For Every Child, Pretoria, South Africa.

- van Rensburg, HC, 2012. Health and health care in South Africa. Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

- Welthagen, N, 2019. Healthcare workers’ knowledge of, insight into and opinion of the proposed National Health Insurance. Solidarity Research Movement, Pretoria, South Africa.

- World Health Organisation, 2016. Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in Africa: a framework for action: main report (English). World Bank Group, Washington, DC. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/735071472096342073/Main-report.

- World Health Organisation, 2019a. Universal health coverage (UHC). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc).

- World Health Organisation, 2019b. Primary health care. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care.

- Yamey, G & Evans, D, 2015. Implementing Pro-Poor Universal Health Coverage: Lessons from country experience. Policy Report from UHC workshop at the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Centre. Italy: The Rockefeller Foundation. https://www.hfgproject.org/policy-report-implementing-pro-poor-universal-health-coverage-lessons-from-country-experience/.