ABSTRACT

The sustainability of community ecotourism under the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) in Zimbabwe is under stress due to shocks including the new coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The pandemic has potential to impede the efforts the community ecotourism sector has been making towards the attainment of the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. The specific objectives of the research were to: (i) document the shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic on the Mahenye community ecotourism project and (ii) suggest possible coping and recovery strategies to the COVID-19 pandemic shocks at the Mahenye community ecotourism project. Qualitative methods were adopted encompassing data mining, expert opinion and key informant interviews. The overall impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Mahenye ecotourism elements have been negative. The present research results could enable ecotourism to be sustainable in the face of shocks emanating from infectious pandemics like COVID-19 and future others.

1. Introduction

The new coronavirus (COVID-19) has been spreading rapidly across the world since the first confirmed case in Wuhan, China in December 2019 (WHO, Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has had a global impact on the tourism industry and by May 2020, all global destinations had imposed some form of travel restrictions, and 45% had totally or partially closed their borders for tourists resulting in revenue and job losses (Spenceley, Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2020; Mudzengi et al., Citation2021). The pandemic has left the world heading for economic recession and humanitarian crisis that will result in reduced funding for African conservation initiatives and increased threats of degradation of environmental resources which ecotourism relies on (World Economic Forum, Citation2020; Worldometer, Citation2020).

A preliminary analysis of an online survey conducted to examine the COVID-19 pandemic impacts on protected area tourism showed that in 38 African countries the pandemic has had significant negative effects on destination visitation, local livelihoods, procurement, conservation and environmental services (Spenceley, Citation2020). Further, the online survey showed a steep drop (61%) in operator’s clients in March 2020 compared to the same time in the previous year (2019), coupled with a decline in future booking requests by 71%. The majority of operators’ clients (about 82%) cancelled their bookings between March and June 2020 (Spenceley, Citation2020). If the COVID-19 pandemic continues it is predicted that, on average, three quarters of local employees will be affected with reduced wages, leave without pay or unemployment (Spenceley, Citation2020). The overall impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on African photographic and hunting tourism as well as environmental conservation will be largely negative (Lindsey et al., Citation2020; Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2021).

The community ecotourism sector under the CAMPFIRE in Zimbabwe is one of the most affected industries by the COVID-19 pandemic (Zamasiya et al., Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic shocks are adding on to the stresses that community ecotourism has been facing over the years. The pandemic is also negatively effecting the sustainability of the Mahenye community ecotourism project (Mudzengi et al., Citation2020a), but has remained resilient even amidst other shocks like climate change, hyperinflation, donor fatigue, reduced international ecotourist visitation and international hunting bans (Gandiwa et al., Citation2013; Mudzengi et al., Citation2020a).

Sustainable community-based ecotourism projects result in good conservation outcomes and positive local development (Newsome & Hassell, Citation2014; Musavengana, Citation2018; Siakwah, Citation2018; Mudzengi et al., Citation2020b). Thus, the lack of ecotourist visitation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic presents a problem. Further, the longer the travel restrictions are in place the more risk there is of biodiversity losses at many wildlife destinations due to declines in tourism user fees leading to less conservation funds for law enforcement and hence increased poaching (Maron, Citation2020). The community ecotourism sector has been making efforts towards promoting pro-poor tourism (Scheyvens, Citation2007), inclusive tourism (Scheyvens & Biddulph, Citation2018), sustainable tourism (Wheeller, Citation1993) and responsible tourism (Wheeller, Citation1991). Given the efforts the community ecotourism sector has been making towards the attainment of the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) it is of interest to proffer strategies that ensure that ecotourism projects such as the Mahenye project remain sustainable in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic shocks.

This study’s specific objectives were to: (i) document the shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic on the Mahenye community ecotourism project and (ii) suggest possible coping and recovery strategies to COVID-19 pandemic shocks at the Mahenye community ecotourism project, southeast Zimbabwe. The results from the above two objectives were then used to propose a management framework for enabling community ecotourism to cope and recover from COVID-19 pandemic shocks.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study area

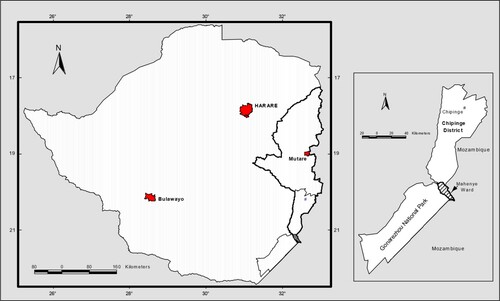

The Mahenye community ecotourism project is a partnership between the local Shangaan-speaking peoples and River Lodges of Africa that owns Chilo Lodge (Machena et al., Citation2017; Mudzengi et al., Citation2020b). Mahenye lies at the extreme southern end of Chipinge District (southeast Zimbabwe) (). Mahenye is characterised by a tropical savanna ecosystem experiencing alternating dry cool winters and wet hot summers. The average monthly maximum temperatures are 25.9°C in July and 36°C in January. The average monthly minimum temperatures range between 9°C in June and 24°C in January (Gandiwa, et al., Citation2011). Annual average rainfall is low ranging between 400 and 600 mm and supports little rain-fed crop cultivation, thus making ecotourism an important non-agricultural source of livelihood (Mudzengi et al., Citation2020b). Mahenye is also mainly covered by mixed mopane (Colophospermum mopane) and Combrertum woodland but a dense riverine forest is found along the Save River supporting a broad range of floral and avian species (Murphree, Citation2001; Gandiwa, Citation2011).

The main ecotourism activities or products at Mahenye are both consumptive such as trophy hunting and fishing and non-consumptive including game drives, photographic safari, birdwatching and identification, canoeing, village tours and scenic views for example at Chivilila Falls along the Save River and lodges (Gohori, Citation2020). The ecotourism project has been sustained by attracting few but high paying visitors and through support from donors, non-governmental organisations and the private sector. The project started as a community public partnership between the local Shangaan-speaking peoples and the then Department of National Parks and Wildlife Management, now Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA) in 1982. This arrangement was formally endorsed when the central government granted appropriate authority over wildlife to Chipinge Rural District Council in 1991 (Murphree, Citation2001). Communal natural resources management initiatives at Mahenye therefore predate the CAMPFIRE.

The other main economic activities in the study area are crop cultivation and livestock rearing. There is also community gardening, marketing crafts and curios to ecotourists and selling traditional beer brewed from palms called Njemani. Some local residents are also engaged in low-paying jobs at the Chilo Lodge which accommodates ecotourists. Some local residents have also been trained as natural resource monitors and game scouts. Further, local residents also perform traditional dances to ecotourists and at cultural festivals (Gohori, Citation2020).

The Mahenye community ecotourism project was chosen as it has been resilient in the face of significant challenges emanating from a changing socio-economic environment in Zimbabwe (Gandiwa Citation2011; WILD Programme, Citation2015; Machena et al., Citation2017; Tchakatumba et al., Citation2019; Mudzengi et al., Citation2020a) and climate change effects (Murphree Citation2001; Mudzengi et al., Citation2020b) and COVID-19 pandemic (Mudzengi et al., Citation2021). The selection of Mahenye was also based on its great potential for ecotourism development as it is part of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area (GLTCA) initiative. The Transfrontier Conservation Areas (TCAs) initiatives seek to promote and facilitate regional peace, tourism, biophysical conservation, cooperation and socio-economic development in Southern Africa (Ferreira, Citation2004).

2.2. Research approach

We approached the research from a qualitative perspective basing the study on data mining, expert opinion, key informant interviews using cellphone calls, e-mailing and social media platforms and researchers’ prior knowledge about Mahenye having carried out research in the area from 2004 to 2020. The study also used the case-study approach. However, the Mahenye community ecotourism project experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic were compared with the situation in other tourism ventures in Africa following methods by Mudzengi et al. (Citation2021).

2.3. Data collection and analysis

Data mining was done using mainly academic literature search engines such as Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science and Science Direct among others. Various search phrases were used in searching for academic articles including ‘COVID-19 and community ecotourism’, ‘COVID-19 and tourism in Zimbabwe, Africa’, ‘COVID-19 and wildlife conservation in Africa’, ‘COVID-19 shocks and ecotourism’, and ‘community ecotourism and environmental sustainability’. The preliminary selection of an academic article for inclusion in the analysis was guided by the articles’ abstract. This was then followed by an in-depth reading of all 77 initially selected articles so as to assess their relevance as data sources for the study. A total of 45 relevant academic documents were finally selected for the analysis.

Expert opinion was sought from a natural resources governance academic at the University of Zimbabwe’s Centre for Applied Social Sciences, hereafter referred to as Expert 1. Expert opinion was also obtained from an environmental management professional at the Environmental Management Agency (EMA) headquarters in Harare, hereafter referred to as Expert 2. A virtual key informant interview was carried out with a senior official at the ZPWMA, hereafter referred to as Key Informant 1. Another key informant interview was carried with an official at the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA) in Harare, hereafter referred to as Key Informant 2. Further, virtual interviews were carried out with 2 key informants with experience in the Mahenye community ecotourism project, hereafter referred to as Key Informant 3 and Key Informant 4. Expert opinion and key informant interviews were sought in order to corroborate data from academic documents and authors’ field experiences. The interviews were conducted between June 2020 and June 2021. Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Chinhoyi University of Technology. The respondents were pre-informed of the academic purposes of the study and gave their informed consent to participate.

A combination of content and thematic analysis was used to sort the large volumes of collected data into focused and meaningful information for the purpose of addressing the research objectives. Data analysis also included identifying and documenting the shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic on community ecotourism in Africa in general and at Mahenye in particular. Mahenye community ecotourism coping and recovery strategies to COVID-19 pandemic shocks were determined from authors’ field experiences, strategies mentioned in the academic documents and from the experts and key informant interviews. The main weakness of the research was the unavailability of quantified data on the shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic at Mahenye due to poor record-keeping protocols and data management systems. However, the use of peer-reviewed journal articles and triangulation of several data sources ensured the reliability of our findings. The information obtained from data analysis and authors’ field experiences was then used to propose a management framework for enabling community ecotourism to cope and recover from COVID-19 shocks. The management framework was adapted from the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) (Scoones, Citation1998; Morse & McNamara, Citation2013). The SLA is a diagnostic tool that provides a framework for understanding and improving the sustainability of livelihood in the face of biophysical, socio-economic and health shocks.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic on the Mahenye community ecotourism project

3.1.1. Reduced photographic and hunting ecotourism visitation

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in reduced income-earning streams for the Mahenye community ecotourism project as photographic tourist visitation and trophy hunting have declined. International ecotourists have either postponed or cancelled their travel arrangements owing to travel restrictions and traveller concerns (Lindsey et al., Citation2020; Yamin, Citation2020). Zimbabwe is also considered as a hotspot for new COVID-19 virus variants based on prototypes that emerged in South Africa (Roberts, Citation2021) and India making Southern Africa a pandemic hotspot. As a result, some tourist source countries have advised their citizens against travelling to Zimbabwe. As a result, most ecotourism operations at Mahenye have been largely suspended except those aimed at protecting wildlife and maintaining infrastructure. Locals have also been subjected to curfews and interprovincial travel bans which have been relaxed depending on the level of COVID-19 infections (Mudzengi et al., Citation2021). Reduced visitation results in less income for the Mahenye community ecotourism project in terms of entrance and lodge fees, selling of crafts and performing cultural dances. Further, it results in reduced income for supporting other community capacity building and resilience projects such as environmental education, fire management, road maintenance and gardening. Less income from ecotourism-related spending leads to a decrease in resources in terms of satisfying lodge employment and maintenance costs. Key Informant 4 had the following to say:

Income for the Chilo Lodge has been reduced as less tourists visit due to COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. The lodge is under difficult to pay workers. Some of the workers have been put on unpaid leave while others have been retrenched. Those engaged in selling crafts and curios have also been affected by reduced arrivals.

3.1.2. Perceived increase in poaching incidences

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a perceived increase in poaching incidences at the Mahenye community ecotourism project due to poor ecosystem monitoring by both anti-poaching staff and tourists who provide an extra eye (Higginbottom et al., Citation2001). Increases in poaching have been reported as providing more fodder for the international anti-hunting lobby against hunting tourism (Machena et al., Citation2017). Lindsey et al. (Citation2020) note that due to the crises associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa local food insecurity and poverty has increased, as governments invest more in health and less in agriculture, leading to communities relying more on natural resources. This poses a heightened threat to biodiversity as communities engage in illegal hunting for bush meat and tree cutting for woodfuel. Cases of human-wildlife conflicts also increase as communities go out into the wilderness in search of natural resources. Key Informant 3 had the following to note:

Poaching at Mahenye has gone up during the COVID-19 pandemic. The anti-poaching operations of community game scouts have been hampered by lack of personal protective equipment, fear of contracting COVID-19 and low morale.

The Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority has had to suspend human-wildlife conflict resolution and mitigation, community engagement and infrastructure development projects due to funding shortages as tourism entrance fees plummet. The suspension is also due to the need to limit COVID-19 transmissions.

3.1.3. Economic downturn

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the world economy heading for a downturn (World Economic Forum, Citation2020). The global economy is estimated to have contracted 4.3 percent in 2020 and economic output will remain more than five (5) percent below pre-pandemic projections in 2021 (World Bank, Citation2021). This leads to a further decline in both photographic and hunting tourism due to lower disposable incomes. Decline in photographic and hunting tourism means a decrease in local community conservation benefits and lower confidence in current wildlife management models (Newsome, Citation2020). An economic downturn also results in inflation as monetary authorities may be tempted to engage in quantitative easing.

These macro-economic shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in a drop in travel-related purchases of artefacts to take home as souvenirs by ecotourists. The shocks have also resulted in a downturn in ecotourism visitation thereby negatively impacting earnings of local traditional dancers who entertained tourists and the profitability of Chilo Lodge. These observations were also corroborated by Key Informants 3 and 4.

3.1.4. Increased calls for hunting and wildlife trade bans

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased calls for hunting and wildlife trade bans owing to speculations that the majority of emerging infectious diseases are linked to wildlife (Jones et al., Citation2008; Mudzengi et al., Citation2020a). The COVID-19 pandemic is believed to have originated at wildlife markets in China and transmitted to humans due to close interaction between wildlife and people. This is not the first time that infectious diseases have been linked to wild animals as between 2002 and 2003, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) which infected thousands of people across the world was also believed to be linked to human-wildlife interactions (WHO, Citation2014). Other significant zoonotic diseases whose transmission has been associated with wildlife include Ebola, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Human Immuno-Deficiency Virus (HIV), bovine tuberculosis, rabies and leptospirosis (Lindsey et al., Citation2020; Yamin, Citation2020). Further, there is a risk of ecotourists spreading COVID-19 to wild animals. Great apes are susceptible to human diseases and there is the possibility of gorillas contracting COVID-19 from tourists (Newsome, Citation2020). Weber et al. (Citation2020) also note that, under normal touristic conditions, gorillas come into close contact with visitors despite strict wildlife–human interaction regulations being in place. This has resulted in gorilla tourism programmes being temporarily suspended in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Uganda (Newsome, Citation2020).

This increased call for hunting and wildlife trade bans has a negative effect on revenue streams from trophy hunting at places like the Mahenye community ecotourism project. This is so as trophy hunting is the biggest income earner for the project. Revenue from trophy hunting at Mahenye was under stress even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit due to some ivory trading restrictions under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (Gandiwa et al., Citation2014; Mudzengi et al., Citation2020a). Consumptive tourism is also under strain due to unilateral restrictive policies by the United States of America (USA) and some European countries limiting the importation of some trophy specimens by hunters (Lindsey et al., Citation2016). The USA Fish and Wildlife Service in 2014 sanctioned a temporary ban on the importation of trophy products of the African elephant into the country. Similarly, some commercial airlines adopted policies that do not allow freight of trophy products from certain species making it even more difficult for potential safari hunters to have trophies from Africa (Di Minin et al., Citation2016).

Hunting and wildlife trade bans have also led to reduced bush meat availability for the local people. This has resulted in less meat protein for the local community. The consumption of less meat protein has negative health effects on the local people. Key Informant 3 also noted that:

The international anti-hunting lobby is well-organised and is pushing hard for the ban of trade in wildlife products. The bans in wildlife trade result in less sport hunting activities and reduced supply of bush meat to the local people. A decrease in bush meat supply lead to the locals less willing to support the ecotourism initiative thereby promoting poaching.

3.2. Possible coping and recovery strategies to COVID-19 pandemic shocks at the Mahenye community ecotourism project

3.2.1. Broadening livelihood options

The findings of this study indicate that the Mahenye community ecotourism project needs to broaden livelihood options and diversify revenue-generating streams in order to cope with and recover from the shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic. This can be achieved through promoting other income-generating activities using local natural resources. Expert 2 noted that:

Additional income generating projects at Mahenye can include bee keeping and honey production, fisheries, crocodile farming, insect and termite extraction, harvesting of the ‘mopane worm’ which is the caterpillar of the emperor moth (Imbrasia belina), fruit collection, mushroom production and fetching leaf litter. Even more there could be the making of natural healthcare products.

Machena et al. (Citation2017) also note that baobab (Adansonia digitata) trees are being used to commercially produce pulp, seed oil, baobab tea infusion and flavoured yoghurt at Mahenye. This is also being done in dry Zimbabwean districts of Binga and Rushinga. Further, natural resources are being used to market products such as traditional remedies for various ailments, dried ‘mopane worms’, honey, dried indigenous vegetables, wild loquat (Uapaca kirkiana) and buffalo thorn (Ziziphus mauritiania) jams and marula (Sclerocarya birrea) oil, jerry and butter. These products are being produced in other dry districts of Zimbabwe such as Matobo, Bulilima Mangwe, Gwanda, Mwenezi, Zaka, Mberengwa, Muzarabani and Rushinga (Mazambani & Dembetembe, Citation2010). Conservation organisations currently operating at Mahenye such as the CAMPFIRE Association and Wildlife in Livelihood Development (WILD) can also provide visible support to other existing core livelihood activities such as crop farming, community vegetable gardening and livestock rearing. The support could be in the form of installing sustainable drip irrigation infrastructure and refurbishing and maintaining livestock watering points to enable enhanced production.

Some of these activities have forward and backward linkages with ecotourism as livestock and crocodile meat, fish, crops, honey, insects, termites, edible caterpillars, mushroom and fruits can be used to serve traditional cuisines to visitors while meat from trophy hunting provides crocodile feed. These local revenue streams are more resilient to global shocks such as reduced international ecotourist visitation and trophy hunting that are emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic. Local people would also link the benefits accruing from these local income-generating streams to conservation thereby will be more willing to provide backing to community ecotourism.

Further, remittances are another livelihood option at Mahenye in the face of socio-economic problems emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic. Remittances by cross-border migrants from Zimbabwe have been used to cushion family members back home in the face of significant shocks emanating from socio-economic and climatic changes in Zimbabwe (Maphosa, Citation2007; Tambara, Citation2011; Damiyano & Dorasamy, Citation2019). According to Key Informant 3:

A segment of the Mahenye population has migrated to urban areas and other countries, particularly South Africa and Mozambique in search of better employment and socio-economic opportunities. These migrants bring remittances back to the community in the form of cash, food, household appliances and agricultural inputs. These remittances can also be an important source of capital for the value addition of veldt products.

3.2.2. Promoting domestic ecotourism visits

The findings of the study indicate that Mahenye community ecotourism should reduce its reliance on international holiday makers and promote domestic visitation. This was also noted by Mutanga et al. (Citation2017) and Mudzengi et al. (Citation2020a). The World Tourism Organisation (WTO) and International Labour Organisation (ILO) (Citation2013) also noted that some southern and eastern African countries heavily reliant on international tourism should foster domestic visitation to enhance resilience to global shocks and build long-term national and regional support for conservation. Fostering domestic ecotourism is being done at Nairobi National Park in Kenya (Lindsey et al., Citation2020) and the initiative has the advantage that the destination is in close proximity to the national capital city with its large concentration of population and capital. Promoting domestic visitation was also noted as a strategy for the tourism industry to recover from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (Rogerson & Rogerson, Citation2021). Accessibility to Mahenye community ecotourism by domestic visitors can be enhanced by tarring and upgrading the link road from the main Birchenough Bridge-Chiredzi-Ngundu highway that is also currently being rehabilitated. This is important as it will provide an all-weather access road for visitors who cannot afford expensive light aircrafts and thereby prefer driving. Promoting domestic ecotourism visits can also be achieved through increasing marketing and reducing barriers to access by reducing prices and offering financial support packages such as holiday allowances for locals. This has to be done during those times when the curfews and interprovincial travel bans are relaxed and in the long-term when the COVID-19 pandemic is over and the subdued economic environment in the country improves. Key Informant 2 noted that:

The Zimbabwe Tourism Authority is promoting domestic tourism and visits to CAMPFIRE sites via enhanced domestic marketing. At the moment the Authority is focusing on creating awareness using digital platforms.

3.2.3. Aggressive marketing

The current study findings indicate towards the need for aggressive marketing of community ecotourism destinations such as Mahenye in the face of COVID-19 pandemic shocks. Aggressive marketing strategies include encouraging ecotourists to postpone their travel arrangements instead of cancelling. This can be done by continuing marketing to potential visitors through reinforcing the message of staying safe from COVID-19 but at the same time reminding them that the destination is still waiting to be explored when they are ready and allowed to travel. The Mahenye community ecotourism project through its linkages of safari operators, tourism promoters, conservation agencies and donor organisations can also promote and offer virtual tourism experiences. This will enable the project to receive some income through selling viewing rights. Chilo Lodge and local community members who are involved in selling handcrafts can also offer discounts and gift coupons to encourage travel-related spending. Dube et al. (Citation2020) also recommended similar promotions for the hospitality industry. Key Informant 2 also noted that:

CAMPFIRE destinations need to market cultural festivals as hybrid events whereby a few visitors may be physically present while the majority attend remotely.

3.2.4. Capacity building in managing community ecotourism during periods of uncertainty

The findings of this study indicate that the Mahenye community should be capacitated in managing ecotourism during periods of uncertainty emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic shocks. The community can be capacitated in using remote communication technology in relaying messages to game scouts once they sight poachers. This is important at a time when people’s movements are restricted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. International conservation partners can also support local people by sharing expertise remotely and funding training programmes on managing community ecotourism in the COVID-19 era (Lindsey et al., Citation2020). Rogerson & Rogerson (Citation2021) also recommended the significance of the contactless economy in the tourism business in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the Mahenye community can be trained on skills of marketing other ecotourism products such as gastronomy. The capacitation will then enable local chefs to teach other people how to prepare Shangaan traditional dishes online for a fee. There is therefore need for effective community ecotourism stakeholder interactions in building the capacity to manage the Mahenye project during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Health authorities can also train the community in disinfecting and deep cleaning of ecotourism amenities and managing COVID-19 cases. The training can lead to ‘COVID-19 Safe’ certification to encourage local people and Chilo Lodge to participate. These certification programmes were also proposed by Dube et al. (Citation2020). The capacitation will enhance community confidence in managing fears and shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, measures should be taken to minimise the transmission of COVID-19 within the local community and from local residents to tourists and vice-versa through masking, regular washing of hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds and sanitising, social distancing, practising basic hygiene and vaccination. Other best practices to minimise COVID-19 transmission include using effective epidemic surveillance systems as what has been done in Chile and in the Caribbean countries (Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO), Citation2020). Expert 2 also noted that:

The Mahenye ecotourism project can allow only visitors with COVID-19 vaccination certificates as is being proposed by similar players elsewhere. Workers at ecotouristic lodges and other operations can also be instructed to have their breaks and lunches scattered across the working hours. Ecotourists should also eat their meals in their rooms. Further, both local residents and visitors should avoid close contact with people who are sick.

3.2.5. Lobbying for a government bailout and other forms of support

The present study findings indicate that the Mahenye community ecotourism project could lobby for a government bailout in form of job support measures, grants, tax deductions and/ or deferments. Key Informant 2 also noted that the government can enter into air travel bridging arrangements to bring in ecotourists from other countries where COVID-19 infection rates are low or under control. The project can also seek for loans with flexible repayment conditions and interest rates close to zero from financial institutions. Further, the project can also develop together with donors a cooperative marketing grant fund to incentivise and support tour operators to start bringing ecotourists to Mahenye once COVID-19 travel restrictions are lifted. These forms of support were also noted by Dube et al. (Citation2020) and Spenceley (Citation2020). In lobbying for support the Mahenye project should work together with other tourism players. This is important because if tourism players work in isolation their voices may not be loud enough to be listened to. However, a substantive bailout may not be feasible in the short-term given the poor state of the Zimbabwean economy.

3.2.6. Developing an international hunting code of ethics and lobbying for legal wildlife trade

The present study findings indicate that the Mahenye community ecotourism project in partnership with other conservation actors need to develop an international hunting code of ethics to wade off increased calls for consumptive safari and wildlife trade bans. The hunting code of ethics should aim to stamp out unsafe, illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade practices that jeopardise human health and environmental conservation. In addressing the disease-transmission risk of the hunting industry Mahenye ecotourism stakeholders can forge partnerships with universities and health institutions to undertake research on the prevention of zoonotic diseases. The research can lead to the creation of an environmental health hub at Mahenye. Expert 2 also noted that:

Hunting industry players need to develop a code of ethics with a buy in from the concerned international community to make it acceptable.

4. Management framework for enabling community ecotourism to cope and recover from COVID-19 pandemic shocks

The shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in community ecotourism initiatives such as Mahenye experiencing significant challenges. Developing management frameworks that ensure that community ecotourism projects remain sustainable in the face of COVID-19 pandemic shocks therefore becomes imperative. This is important if community ecotourism is to continue making efforts towards the attainment of the SDGs. The proposed management framework () shows the COVID-19 shocks impacting community ecotourism elements and possible management coping and recovery strategies as well as livelihood outcomes. The framework is largely related to the one developed by Mudzengi et al. (Citation2020a) on ensuring ecotourism resilience to shocks induced by a changing environment.

Table 1. Proposed management framework for community ecotourism to cope and recover from COVID-19 shocks (Source: Authors).

5. Conclusion

The shocks emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic at the Mahenye community ecotourism project include decline in ecotourism visitation, upsurge in poaching incidences, global economic downturn and increased intensity of lobbying for further international hunting and wildlife trade bans. Possible coping and recovery strategies to the COVID-19 pandemic shocks at Mahenye include broadening livelihood options, promoting domestic visitation, aggressive marketing, capacity building, lobbying for government support, promoting effective stakeholder interactions and developing an international hunting code of ethics. However, these coping and recovery strategies may have limited potential due to the poor macro-economic environment in the country. Some of the strategies may have to be implemented in the long term with the hope that measures being put in place to revive the economy succeed. The present research results could inform environmental policy makers on strategies of ensuring the sustainable management of community ecotourism projects in a changing operating environment emanating from infectious pandemics. To this end, the current community ecotourism model can be adapted to be more resilient using our management framework for coping and recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic shocks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACF (African Conservation Foundation), 2020. How is the novel coronavirus connected to wildlife? https://africanconservation.org/how-is-the-novel-coronavirus-connected-to-wildlife/ Accessed 30 May 2020.

- Damiyano, D & Dorasamy, N, 2019. The diaspora effect to poverty alleviation in Zimbabwe. Restaurant Business 118(11), 381–416.

- Di Minin, E, Leader-Williams, N & Bradshaw, CJ, 2016. Banning trophy hunting will exacerbate biodiversity loss. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 31, 99–102.

- Dube, K, Nhamo, G & Chikodzi, D, 2020. COVID-19 cripples global restraint and hospitality industry. Current Issues in Tourism, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1773416

- Ferreira, S, 2004. Problems associated with tourism development in Southern Africa: The case of Transfrontier Conservation areas. Geographical Journal 60, 301–10.

- Gandiwa, E, 2011. Preliminary assessment of illegal hunting by communities adjacent to the northern Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe. Tropical Conservation Science 4(4), 445–67.

- Gandiwa, E, Chikorowondo, G, Zisadza-Gandiwa, P & Muvengwi, J, 2011. Structure and composition of Androstachys johnsonii woodland across various strata in Gonarezhou National Park, south-east Zimbabwe. Tropical Conservation Science 4(2), 218–29.

- Gandiwa, E, Heitkönig, IMA, Lokhorst, AM, Prins, HHT & Leeuwis, C, 2013. Illegal hunting and law enforcement during a period of economic decline in Zimbabwe: A case study of northern Gonarezhou National Park and adjacent areas. Journal for Nature Conservation 21, 133–42.

- Gandiwa, E, Sprangers, S, van Bommel, S, Heitkönig, IMA, Leeuwis, C & Prins, HHT, 2014. Spill-over effect in media framing: representations of wildlife conservation in Zimbabwean and international media, 2009–2010. Journal for Nature Conservation 22, 413–23.

- Gohori, O, 2020. Towards a tourism and community development framework: An African perspective. PhD thesis, North-West University.

- Higginbottom, K, Northrope, C & Green, R, 2001. Positive effects of wildlife tourism on wildlife. CRC Sustainable Tourism, Gold Coast.

- Jones, KE, Patel, NG, Levy, MA, Storeygard, A, Balk, D, Gittleman, JL & Daszak, P, 2008. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536

- Lindsey, PA, Balme, GA, Funston, PJ, Henschel, PH & Hunter, LTB, 2016. Life after Cecil: channeling global outrage into funding for conservation in Africa. Conservation Letters 9(4), 296–301.

- Lindsey, P, Allan, J, Brehony, P, Dickman, A, Robson, A, Begg, C, Bhammar, H, Blanken, L, Breuer, T, Fitzgerald, K, Flyman, M, Gandiwa, P, Giva, N, Kaelo, D, Nampindo, S, Nyambe, N, Steiner, K, Parker, A, Roe, D, Thomson, P, Trimble, M, Caron, A & Tyrrell, P, 2020. Conserving Africa’s wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nature Ecology & Evolution, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6

- Machena, C, Mwakiwa, E & Gandiwa, E, 2017. Review of the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) and Community Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM) models. Government of Zimbabwe & European Union, Harare.

- Maphosa, F, 2007. Remittances and development: The impact of migration to South Africa on rural livelihoods in southern Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa 24(11), 123–36.

- Maron, D, 2020. Poaching threats loom as wildlife safaris put on hold due to COVID-19. www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2020/04/wildlife-safaris-halted-for-covid-boost-poaching-threat Accessed 28 May 2020.

- Mazambani, D & Dembetembe, P, 2010. Community Based Natural Resources Management Stocktaking Assessment. Zimbabwe CBNRM Country Profile. CBNRM Forum, CAMPFIRE Association, Harare.

- Morse, S & McNamara, N, 2013. The theory behind the sustainable livelihood approach. Sustainable Livelihood Approach, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6268-8_2

- Mudzengi, BK, Gandiwa, E, Muboko, N & Mutanga, CN, 2020a. Towards sustainable community conservation in tropical savanna ecosystem: a management framework for ecotourism ventures in a changing environment. Environment, Development & Sustainability, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00772-4

- Mudzengi, BK, Gandiwa, E, Muboko, N, & Mutanga, CN, 2020b. Ecotourism and sustainable development in rural communities bordering protected areas. A case study of opportunities and challenges for Mahenye, Chipinge District, southeast Zimbabwe. In Berrahmouni, N. (Ed.), Biodiversity: The central role in the sustainable development of Africa. Nature & Faune 33(1), 70–7.

- Mudzengi, BK, Gandiwa, E, Muboko, N, Mutanga, CN & Chiutsi, S, 2021. Ecotourism resilience: The case of Mahenye community project, Chipinge District, Zimbabwe. African Journal of hospitality. Tourism and Leisure 10(2), 459–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-111

- Muposhi, VK, Gandiwa, E, Bartels, P & Makuza, SM, 2016a. Trophy hunting, conservation, and rural development in Zimbabwe: issues, options, and implications. International Journal of Biodiversity, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8763980

- Muposhi, VK, Gandiwa, E, Makuza, SM & Bartels, P, 2016b. Trophy hunting and perceived risk in closed ecosystems: flight behaviour of three gregarious African ungulates in a semi-arid tropical savanna. Austral Ecology, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/aec12367

- Muposhi, VK, Gandiwa, E, Makuza, SM & Bartels, P, 2017. Ecological, physiological, genetic trade-offs and socio-economic Implications of trophy hunting as a conservation tool: A narrative review. The Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences 27(1), 1–14.

- Murphree, M, 2001. Community, council & client: A case study in ecotourism development from Mahenye, Zimbabwe. In D Hulme & M Murphree (Eds.), African wildlife & livelihoods: The promise and performance of community conservation. James Currey, Oxford, 177–193.

- Musavengana, R, 2018. Toward pro-poor economic development in Zimbabwe: The role of pro-poor tourism. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 7(1), 1–14.

- Mutanga, CN, Gandiwa, E & Muboko, N, 2017. An analysis of tourist trends in northern Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe, 1991–2014. Cogent Social Sciences 3(1), 1392921. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1392921

- Newsome, D, 2020. The collapse of tourism and its impact on wildlife tourism destinations. Journal of Tourism Futures, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2020-0053

- Newsome, D & Hassell, S, 2014. Tourism and conservation in Madagascar: the importance of Andasibe National Park. Koedoe 56(2), 1–8.

- PAHO, 2020. PAHO outlines best practices to control COVID-19 pandemic. reliefweb.int/report/world/paho-outlines-best-practices-to-control-covid-19-pandemic Accessed 1 April 2021.

- Roberts, M, 2021. South Africa coronavirus variant: What is the risk? bbc.com/news/health-55534727.

- Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2021. COVID-19 and changing tourism demand: research review and policy implications for South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 10(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720-83

- Scheyvens, R, 2007. Exploring the tourism-poverty nexus. Current Issues in Tourism 10(2&3), 231–254.

- Scheyvens, R & Biddulph, R, 2018. Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies 20(4), 589–609.

- Scoones, I, 1998. Sustanable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton.

- Siakwah, P, 2018. Tourism geographies and spatial distribution of tourists sites in Ghana. African Journal of hospitality. Tourism and Leisure 7(1), 1–19.

- Spenceley, A, 2020. COVID-19 and tourism in Africa’s protected areas: impacts and recovery needs. Eurata Consortium, Brussels.

- Tambara, J, 2011. The impact of remittances on Zimbabwean economic development. MSc dissertation, University of Zimbabwe.

- Tchakatumba, PK, Gandiwa, E, Mwakiwa, E, Clegg, B & Nyasha, S, 2019. Does the CAMPFIRE ensure economic benefits from wildlife to households in Zimbabwe? Ecosystems and People 15(1), 119–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2019.1599070

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organisation), 2020. Tourism and COVID-19 Coronavirus. www.unwto.org/tourism-covid-19-coronavirus Accessed 27 May 2020.

- World Bank, 2021. Global Economic Prospects, January 2021. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1612-3.

- Weber, A, Kalema-Zikusoka, G & Stevens, NJ, 2020. Lack of rule-adherence during mountain gorilla tourism encounters in Bwindi impenetrable national park, Uganda, places gorillas at risk from human disease. Frontiers in Public Health 8, 1–13.

- Wheeller, B, 1991. Tourism’s troubled times: responsible tourism is not the answer. Tourism Management 12(2), 91–6.

- Wheeller, B, 1993. Sustaining the ego. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 1(2), 121–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589309450710

- WHO (World Health Organisation), 2014. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004 04 21/en/ Accessed 30 May 2020.

- WHO (World Health Organisation), 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 Accessed 27 May 2020.

- WILD (Wildlife in Livelihood Development) Programme, 2015. Jamanda Community Conservancy. www.wild-africa.org/jamanda-conservancy/4588094811 Accessed 27 May 2020.

- World Economic Forum, 2020. The COVID-19 recession could be far worse than 2008 – here’s why. www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/mapping-covid-19-recession Accessed 27 May 2020.

- Worldometer, 2020. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. www.wordometers.info/coronavirus Accessed 27 May 2020.

- WTO (World Trade Organisation) & ILO (International Labour Organisation), 2013. Economic Crisis, International Tourism Decline and its Impact on the poor. https://go.nature.com/2DLxAaw Accessed 28 August 2020.

- Yamin, M, 2020. Counting the cost of COVID-19. International Journal of Information Technology 12(2), 311–7.

- Zamasiya, B, Ndlovu, N, Mabikwa, N & Dhliwayo, M, 2020. The effects of COVID 19 pandemic on wildlife reliant communities and conservation efforts in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association, Harare.