ABSTRACT

In the Fourth Industrial Revolution, academics should enhance entrepreneurial capacity to leverage digital-based advances and knowledge capital to support academic economic growth. A scoping review based on the Joanna Briggs Institute’s guiding principles, using Krueger’s intention-based entrepreneurship model as the theoretical framework, was undertaken to determine the extent of the literature related to characteristics, attributes, behaviours, enablers, and barriers of academic entrepreneurship in Higher Education Institutions in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Twenty articles were identified and included. The most common academic entrepreneurial characteristics included hunger for success, desire for independence, innovation, creativity, futuristic thinking, and self-esteem. For entrepreneurship to flourish, donor support, strong regulatory systems, political and macroeconomic stability were necessary. Characteristics such as innovation, creativity and futuristic thinking were tied to academic entrepreneurship. Further research on enablers and barriers is suggested to guide academics in LMIC universities with their transition to entrepreneurship as their engagement with society develops.

Introduction

The world economy is changing with knowledge supplanting physical capital as a source of wealth, requiring Higher Education Institutions (HEI), as the prime creators and conveyors of knowledge, to narrow development gaps between high-income countries (HIC) and low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [World Bank, Citation2000].

Etzkowitz [Citation1983], was the first to use the term ‘entrepreneurial universities’. He introduced the term to describe universities’ role in economic and regional development. His work suggested that the entrepreneurial university offers a new stage in the development of HEI. Since broad economic development has become the HEI “third mission’ (after teaching and research), entrepreneurship has become critical to HEI impact and success. Broström et al. [Citation2021], indicate that this third mission is expected to contribute to technological innovation, regional development, and solving societal problems. They also describe the complex field of emerging financial opportunities and constraints, policy challenges and asymmetrical delivery of results given the resources and opportunities currently available to researchers. It is clear that this presents uncertainly regarding the role that HEI and academics should play in society [Albats et al., Citation2018].

Expectations that industry will continue to drive economic growth are receding and instead, the fundamental economic actors are likely to be organisations originating from within or closely associated with entrepreneurial HEI. This represents an interactive bilateral flow of influence between the HEI and an increasingly knowledge-based society, in contrast to the traditionally linear model of innovation. In the transition from industrial to knowledge-based society, clusters and regions rely increasingly on HEI to secure a ‘smart specialisation’ niche in the global arena, with their research, education, and entrepreneurial capabilities. The interaction between HEI, industry and government (idiomatically the ‘Triple Helix’) is becoming the central focus of innovation theory and practice in HIC and LMIC [Etzkowitz, Citation2013].

The fourth industrial revolution (4IR) simplifies this fundamental societal shift with the potential to impact and disrupt vocations, economies and industries across nations. First coined by Klaus Schwab, the founder and chairperson of the World Economic Forum, 4IR describes a world where technologies fuse and boundaries between the physical, digital and biological spheres become blurred. Schwab asserts that the 4IR is not merely a prolongation of the digital (third industrial) revolution but a distinct fourth revolution characterised by an unprecedented velocity (4IR is evolving at an exponential rather than the linear rate with new technologies begetting newer and even more capable technologies), breadth and depth (4IR is not only changing the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of doing things but also ‘who’ we are) and systems-impact (4IR involves the transformation of entire systems, across and within countries, companies, industries and society). Knowledge production and its application (innovation) is the force directing the 4IR, with HEI regarded as one of the foremost places to pursue the forward-thinking ideas required. However, HEI must adapt their incremental and conservative research development approach, developing bolder and more innovative approaches to align with the 4IR velocity and scope [Schwab, Citation2016].

Understanding the disruptive potential of the 4IR is important for all nations, especially for LMIC’s where its ultimate impact remains unknown. Schwab highlighted the risks of global manufacturing being ‘re-shored’ back to advanced economies from current LMIC locations should access to low-cost labour no longer be a requirement for economic competitiveness. Such a reversal could overturn some of the progress made over recent years to shrink the economic gap between industrialised and developing economies. The counterargument proposes that the speed of the 4IR advance might enable a faster closing of the economic gap between the developed and under-developed worlds, leapfrogging LMIC to more advanced economic stages [Schwab, Citation2016].

Irrespective of which view prevails, one cannot ignore the regional impact of the entrepreneurial HEI on economic and social innovation in LMIC where poverty persists. Marginalised people are driven to entrepreneurship by defensive and regressive factors such as unemployment, which contrasts with the thriving opportunity-seeking behaviour that prevails in HICs [Vivarelli, Citation2012]. Thus, in the HIC university settings, academic and HEI entrepreneurship is focused on activities in partnership with industry driven by the need to thrive and profit. On the other hand, LMIC academics and HEI face the overwhelming need to pursue social entrepreneurial activities attempting to alleviate poverty and high unemployment. Sutter et al. [Citation2019] identified three common assumptions about the challenges that need to be addressed to enable thriving entrepreneurial pursuits in LMIC. These include providing resources and external mentorship, addressing the social exclusion of the marginalised and effecting new economic models as alternatives to capitalism.

A case study at a prominent Brazilian university found that the narrow economic metric used to assess entrepreneurial HEI performance in the HIC, fell short when assessing entrepreneurial HEI impact in the LMIC context, where HEI lie at the heart of regional efforts to address social and economic challenges. An LMIC tailored entrepreneurial HEI model is therefore vital to assist HEI to play a positive role within their regions through various social and economic paths as the impact of the 4IR on LMIC unfolds [Thomas & Pugh, Citation2020].

It will be the HEI employees who pursue entrepreneurial activities beyond their traditional research and lecturing duties to meet an HEI third mission objectives [Grünhagen & Volkmann, Citation2014], as it is not organisations who innovate but rather the individuals within these organisations who do [Krueger, Citation2000]. Understanding what encourages or discourages individual entrepreneurship requires insight into how people perceive opportunities. Intention-based models, where attitudes influence behaviour via intentions, provide a coherent and robust framework for understanding the entrepreneurial process [Krueger, Citation1993; Krueger, Citation2000]. Based on these concepts, Krueger developed an entrepreneurial intention-based model [adapted from Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982; Krueger & Brazeal, Citation1994; Krueger, Citation2000] explaining how opportunities emerge (detailed in [Krueger, Citation2009]). This is the theoretical basis used for this scoping review.

Figure 1. Krueger Intention-Based Model [Krueger, Citation2009].

![Figure 1. Krueger Intention-Based Model [Krueger, Citation2009].](/cms/asset/f1ae4775-f40f-4290-a3f2-21a0fd825daf/cdsa_a_2027230_f0001_ob.jpg)

The Krueger and Brazeal Entrepreneurial Potential (KEP) model [Krueger & Brazeal, Citation1994] is a synthesis of Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [Ajzen, Citation1991] and Shapero’s Entrepreneurial Event (SEE) model [Shapero and Sokol, Citation1982]. While the TPB model explains the behaviour of individuals in general, the SEE model was specifically developed to understand entrepreneurial intention and behaviour. The TPB posits that behavioural intentions, which directly provide the incentive to execute the behaviour, are determined by: 1) attitude toward the behaviour (an individual’s perception of the desirability of an outcome), 2) subjective norm (perceived social pressure), and 3) perceived behavioural control (the extent to which the behaviour is perceived to be within the individual’s ability), which is similar to Bandura’s self-efficacy concept [Bandura, Citation1982]. On the other hand, the SEE model assumes that human behaviour is guided by inertia (sum of ‘vectors’) until interrupted or ‘displaced’. Whether the displacement has a negative (e.g. loss of employment) or positive (e.g. receiving inheritance) origin, it precipitates a behavioural change. This change is based on the relative ‘credibility’ of alternative courses of action predicated on that individual’s inherent ‘propensity to act’ on available opportunities. The behavioural options in the SEE model are therefore based on the: 1) perceived feasibility of the behavioural options (compares with the TPB perceived behavioural control) and 2) perceived desirability (generally corresponds to the TPB’s ‘attitude to behaviour’ and ‘subjective norms’), of the different courses of action. The propensity to act represents the individuals’ desire and willingness to perform a specific behaviour.

Intention-based models of entrepreneurial activity (TPB, SEE, KEP) have shown that situational and individual variables are exogenous to the entrepreneurial act and thus poor predictors of entrepreneurial action. Rather, these variables have an indirect influence on entrepreneurship by influencing key attitudes and general motivation [Krueger, Citation2000]. The Krueger intention-based model () proposes that these exogenous factors influence intentions and behaviour (action) through influencing one or more critical attitudes.

As the involvement of the individual academic is central to the HEI entrepreneurship endeavour, a complete picture of HEI entrepreneurship may only arise when considering the individual academics and the factors that drive their transition to entrepreneurship [Goethner et al., Citation2012]. This paper aims to review the published literature describing the characteristics and attributes of academics engaged in entrepreneurial activities in HEI in LMIC, and the enablers of, or barriers to, their entrepreneurial activation, using the Kreuger intention-based model.

Materials and methods

Study design

This review was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute’s scoping review method and aimed to systematically identify evidence and research gaps regarding academic entrepreneurial activation [Peters et al., Citation2015; Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005].

Search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria

The scoping review followed a comprehensive, systematic search process identifying literature relating to the characteristics (attributes) and behaviours of entrepreneurial university academics; and the enablers (drivers) and barriers (inhibitors) they face within the HEI sector in LMIC. The search strategy and screening included: 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, 5) collating, summarising and reporting the results [Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005].

A comprehensive search of relevant keywords in indexed journals related to the generic terms ‘entrepreneurial’, ‘academic’, and ‘low and middle-income countries’ (see Additional File 1), was developed according to the research question and based on the PCC (population, concept, and context) framework. This scoping review includes university academics (population), characteristics (attributes), behaviours and enablers (drivers) and barriers (inhibitors) associated with entrepreneurial activities (concept) in the HEI sector in LMIC (context), as outlined in . An initial search was conducted in PubMed and Emerald Insight databases and identified records imported into EndNote where three review team members (AF, MJ, WM) checked whether relevant studies already known to the review team were present. After this initial search, we modified the search strategy to increase its comprehensiveness. The final search was conducted using the following databases: EBSCO (CINAHL, Health Source, Econlit, and Business Source Ultimate), PubMed, Emerald Insight, ProQuest and Science Direct. These electronic databases were selected due to their relevance and comprehensiveness to the review objectives. The last online search of the databases was on 31 August 2019. To complement the electronic search, the team manually searched the reference list of included studies.

Table 1. PCC framework.

Based on the scoping review aims and the PCC framework, the studies included met the following parameters: 1) population: academics or university lecturers, professors and researchers (18 years and older), 2) phenomenon of interest/concept: characteristics (attributes), behaviours, enablers (drivers) and barriers (inhibitors) associated with entrepreneurial activities, and 3) setting: HEI (academic) sector in LMIC or developing countries.

We only included studies published in English. The risk of bias was not conducted, as stipulated in the scoping review manual [Peters et al., Citation2015].

Study selection and data extraction

All identified records from the various electronic databases and reference searching were collated using EndNote reference management software. The articles were exported into Covidence [Covidence Software, Citation2020], where duplicates were removed, and the review team performed independent screening of titles, abstracts and the full text. As part of training and setting a consistent screening pattern in both title and abstract and full-text stages, the review team screened 50 records together. Disagreements arising during the screening process were consultatively resolved.

A standardised data abstraction form developed a priori was used to collect data variables. The data abstraction form was piloted on a sample of ten included articles and adjusted accordingly. The following data variables were abstracted from the included studies: author(s) and year study were published; study title; country or region where the research was conducted; the aims or objectives of the study; reported entrepreneurial characteristics (attributes), behaviours, enablers (drivers) and barriers (inhibitors). Three reviewers carried out data abstraction, whilst two other reviewers checked on the consistency and accuracy of the data.

Results

Search and selection of articles

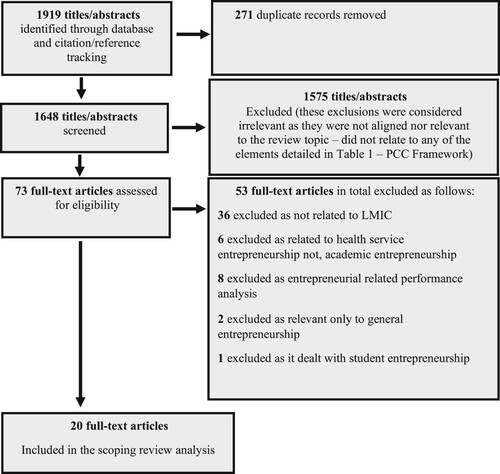

The results of the literature search are detailed in (PRISMA flowchart). Seventy-three (73) full-text articles were screened for eligibility. Of these, 20 articles met the inclusion criteria (see details in Additional File 3). The 53 articles excluded are listed in Additional File 2.

Overview

Using Krueger’s intention-based model, the 20 selected articles all explored the exogenous factors which influence the attitudes that help develop academic entrepreneurial intention. However, coverage of entrepreneurial attitude, intention, propensity to act and behaviour was variable across the 20 articles, with only one applying an intention-based model as its theoretical framework.

Characteristics/attributes (exogenous factors)

All the articles selected explored and evaluated exogenous factors (such as knowledge) and how these factors influence HEI related entrepreneurship. According to the Krueger intention-based model, an entrepreneurial orientation typically requires that an intention is explained and predicted by desirability and feasibility.

Heng et al. [Citation2012], using TPB and SEE as a theoretical basis, performed eight structured case study interviews with 1) entrepreneurs from university incubators and 2) academics at various stages of commercialisation in three Malaysian Research Universities. They found that personal characteristics such as the need for achievement, the desire for independence and an internal locus of control were common in both groups (described in ). They concluded that the perception of feasibility, which is governed by perceived self-efficacy, has a significant impact on the decision making of an academic researcher to commercialise. They also argued that knowledge directly influences perception toward behaving entrepreneurially, rather than on the behaviour itself. Furthermore, academic researchers reported that the lack of business and marketing acumen harmed entrepreneurial attitude, and this may point to the importance of marrying academic researchers scientific and technical strengths with industry’s business knowledge, if HEI related entrepreneurship is to be cultivated.

Table 2. Exogenous factors that may promote academic entrepreneurship.

Using the framework of professional growth linked to psychological empowerment, a survey among 397 Professors and students from the Medical Sciences University and Persian Gulf University, Iran, investigated the impact of academic education on the development of entrepreneurial characteristics amongst students [Behroozi, Citation2012]. Entrepreneurial exogenous factors investigated in this study included controlled risk-taking, innovation and creativity, self-esteem and autonomy, flexibility, futuristic thinking, extroversion, resilience, openness to suggestions and criticism, perceptiveness, hunger for success, dynamism and leadership ability (also described in ). They found that whilst academic education positively influenced flexibility and openness to suggestions, it generally had limited influence on most other entrepreneurial exogenous factors.

Personality, motivation, ability, and aptitude (antecedents of desirability and self-efficacy elucidated by Krueger’s intention-based model) were identified as factors influencing the behaviour of those involved with HEI entrepreneurship, in a study using a qualitative comparative analysis approach [Freitas et al., Citation2013]. This study reports on 7 interviews with entrepreneurs regarding the emergence of their embryonic high-tech academic spin-off in Brazil and explains how exogenous factors impact intentions and behaviours indirectly through influencing desirability and feasibility.

Characteristics/attributes (attitudes)

Academic entrepreneurial attitude has been identified as the significant antecedent of entrepreneurial intention [Dabic et al., Citation2015; Fischer et al., Citation2019]. In examining entrepreneurial attitude among Croatian and Spanish university academics, Dabic et al. [Citation2015] postulated that attitude is influenced by perceived utility, creativity and entrepreneurial experience. In examining the samples from Croatia and Spain, which differ in terms of university systems, economic context and innovation systems, the study found no significant difference in academic entrepreneurial attitudes across the two regions. This might suggest that any change or intervention to promote a positive academic entrepreneurial attitude follows a similar trajectory regardless of the context or roles of the academics. However, in developing countries, challenges on promoting academic entrepreneurship still exist, and HEI need to navigate these challenges through promoting a more flexible academic career and the introduction of business ‘friendlier’ policies that facilitate the establishment of knowledge-intensive ventures in these poorer economic circumstances [Fischer et al., Citation2019].

In their analysis of academic entrepreneurship in developing economies, Cantu-Ortiz et al. [Citation2017] suggest that business experience affects the academics’ entrepreneurial attitude, where the more experienced the academic, the easier it is for them to identify opportunities for commercialisation.

Behaviour (action)

Globally, HEI have evolved in response to changing social, economic and political pressures. The initial significant evolution in the twentieth century was a transformation from institutions of cultural preservation to institutions creating and disseminating knowledge. In recent years, economic competitiveness is frequently achieved from technical innovation and the competitive use of knowledge. With the growing demand for valuable and exploitable research and steadily dwindling academic research funding, universities are required to undertake translational research that yields products and new commercial enterprises [Freitas et al., Citation2013; Gur et al., Citation2017; Belitski et al., Citation2019].

Belarus, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan are representative transition economies with substantial research commercialisation activity [Belitski et al., Citation2019]. Generally, Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) in these countries do not establish spin-offs or start-ups; instead, they perform an information brokerage function between a university and investors. Collaboration with industry remains the preferred channel of knowledge transfer for achieving entrepreneurial outcomes. Using a mixed-method quantitative survey and one-on-one interview approach for 424 commercially active scientists from 20 universities from these countries, Belitski et al. [Citation2019] investigated individual characteristics, university (organisational) and ecosystem factors that affect the likelihood of research commercialisation in these transitional countries. They found that the number of publications in the last five years, the academic position of the scientist at the university, the proportionate share of research in the scientists’ total workload, the level of their research funding, and the scientist’s awareness of technology transfer, are a proxy for the scientist’s level of engagement with commercialisation (). Controlling for a broad range of country-level factors such as Gross Domestic Product and population size, they found that research commercialisation by scientists requires the capacity to build strong external partnerships and networks with country stakeholders such as entrepreneurs, universities, local and national government and private industry. They found that academic position, age, publication record, research output and quality, or the self-sponsorship of research had little or no effect on commercialisation income.

Table 3. Action (behaviour) that might promote academic entrepreneurship.

Lubango [Citation2015] conducted an analysis of 1702 patents and 332 science sources (that had linkages with patents) filed by South African enterprises between 1976 and 2010. He found that co- inventors’ and co-authors’ established collaborative networks (facilitating opportunities and entrepreneurial alertness) and their internationally acclaimed academic reputations (measured by the h-index) enhanced the flow of academic knowledge into industrial patents applied in South African enterprises. These collaborations offer mutual gains, including the exchange of technological information and sharing of research and development cost and risks, accumulation of new skills, broadened the scope of activities and reducing technological uncertainty, shared research and development facilities, cross-fertilisation of ideas, additional expertise in new innovative technologies, expanded networks and provision of highly trained personnel [Gur et al., Citation2017].

A further South African study found that most inventors or co-inventors held positions in industry or in specialised parastatal institutions prior to patent application. The study supports the notion that industrial work experience enhances the inventive capacity and intention of academic entrepreneurs [Lubango & Pouris, Citation2007].

Enablers/barriers (propensity to act/precipitating event)

Bader et al. [Citation2010] noted that an analysis of health innovation in Ghana recommended the funding commitment to the science and technology industry be increased to drive health innovation. Their case study of 48 science-based health innovators found that for entrepreneurship to flourish, health and biosciences research institutions need donor support, access to venture capital, foreign collaboration, and strong regulatory systems. In addition, academic entrepreneurial activities are developed when there is political and macroeconomic stability, and where locally owned knowledge is encouraged (). Furthermore, mobilising other stakeholders in health product development, such as those who specialise in indigenous medicines or diagnostics (environmental factors), expanded entrepreneurial platforms.

Table 4. Propensity to act (enablers) on entrepreneurship.

China, the world’s largest emerging economy, has enjoyed increased institutional and organisational support for academic entrepreneurship. Based on a sample of 248 academic entrepreneurs surveyed from 200 Chinese universities and research institutes, it was found that successful entrepreneurial academics had distinct professional, scholarly, and entrepreneurial traits [Guo et al., Citation2019]. These individuals actively approach their multiple identities through role integration, cognitive flexibility, heightened creativity, and high levels of performance (reflected in their ability to manage uncertainty and change, being opportunistic and having high levels of perceived self-efficacy). They argue that this role integration allows academic entrepreneurs to alleviate role conflict, enhance role legitimacy, and consequently obtain better access to social, cognitive and emotional resources. These findings support an understanding of how academics can embrace entrepreneurial identity and align to collaborate and gain institutional support with business and industry stakeholders.

Furthermore, this study found that this integration is weakened by social capital inertia (which reflects reticence in human sociability, that is the ability to work together, solve complex problems, and form the organisations that make up society). Conversely, role integration, which involves attitude and intention, may be strengthened by a capacity for adaptability of task approach, reflecting an individual's ability to balance an emphasis on goal achievement and strategic direction, with the need to identify and pursue actions to improve fit and continuous adaptability.

In Mexico, fostering academic entrepreneurship was found to be difficult because academics are highly specialised in their research domains and that expanding the academic’s area of expertise to the realm of entrepreneurship was not as feasible as building a team that included commercial, finance and operations expertise () [Cantu-Ortiz et al., Citation2017]. These authors found that their study of 48 spin-off projects in science and technology doctoral research established that the crucial enablers for academic entrepreneurial activities are: 1) a functional basic research platform, 2) oiling the entrepreneurship ecosystem with resources (funding and workforce) and incentives (financial and academic status), 3) forming highly specialised entrepreneurial teams 4) establishing generous and flexible intellectual property policies and 5) aligning technology together with business incubation. These were found to provide solutions to the barriers that hamper Mexico’s entrepreneurship ecosystem (high technology challenges, research skills shortages and technology transfer hindrances).

Table 5. Propensity to act (barriers/inhibitors) on entrepreneurship.

A study of 680 faculty members from 70 Brazilian higher education institutes evaluated university-level institutional settings to understand the role of the academic environment on academic entrepreneurship [Fischer et al., Citation2019]. The study postulated that when universities in developing countries are located in weak entrepreneurial ecosystems, initiatives targeted at nurturing academic spin-offs are likely to fail.

In trying to understand the effects of links among enterprises, universities and government on innovation, a study in Mexico on 19188 enterprises concluded that enterprise-university-government linkages are vital to entrepreneurial innovation [Guerrero & Urbano, Citation2017]. In addition, these linkages were likely to promote the diverse perspectives needed to allow open innovation, high-growth entrepreneurship and knowledge transfer in research. The study also found that higher levels of criminality negatively affected entrepreneurial innovation activity, requiring the enterprise-university-government linkage to guard against such [Guerrero & Urbano, Citation2017].

Intention-based models

The intention-based models postulate that a person’s behaviour or action towards doing something tangible is determined by the intention to perform that action. Of the 20 studies, only one was based on an intention-based model (Heng et al., Citation2012), which used TPB and SEE as its theoretical framework. This study established that exogenous factors (in this instance knowledge) do not directly influence entrepreneurial action, but rather the attitude toward entrepreneurial intention and behaviour.

Discussion

This review examined the exogenous factors, attitudes and actions of entrepreneurial HEI academics in LMIC, and the enablers and barriers (propensity to act/precipitating event) impacting their entrepreneurial activation. The study highlights the paucity of literature relating to understanding entrepreneurial academics in LMIC’s using intention-based models as the theoretical basis. This deficiency exists despite the affirmation of the central role HEI and academics must play in LMIC development within the changing knowledge economy [Heng et al., Citation2012; Behroozi, Citation2012; Gur et al., Citation2017; Al-Bader et al., Citation2010; Chang et al., Citation2006].

We found that the ‘Enabler’ theme attracted the most coverage of the 20 articles reviewed, with support from the HEI (and to a lesser extent the State) identified as the most significant factor enabling academic entrepreneurial activation; although one study also identified industry relationships and funding as being more effective [Belitski et al., Citation2019]. To a lesser extent, incentives, access to funding and the entrepreneurial orientation of the HEI were also identified as important enablers in driving the propensity to act.

There are differences between HIC and LMIC HEI entrepreneurship, with many of the reviewed studies noting a lack of investigation of HEI related entrepreneurship in LMIC (Belitski et al., Citation2019; Dalmarco et al., Citation2018; Guerrero et al., Citation2017; Kafouros et al., Citation2015). The 20 studies reinforced a theme of shortages of resources (such as incentives, funding, and industry support). These shortages may be attributable to the underdeveloped economic environments in LMIC settings and require universities and industries to develop a conducive environment that promotes academic entrepreneurship. One such opportunity is for universities in LMIC to embrace and harness the 4IR to develop an environment (infrastructure, technology, artificial intelligence and business models) that capacitates, motivates and allows academics to fully engage their knowledge, and which facilitates entrepreneurship [Nkosi et al., Citation2020]. It is possible, if this strategy is effectively applied, that LMIC HEI may dramatically enhance its effectiveness and reputation, leap-frogging the typically linear development path.

The review also found that when using traditional HIC based intention and action domains in evaluating entrepreneurial enablers in LMIC HEI settings that, these metrics did relate to the activities being taking place in the LMIC HEI. The development of an LMIC approach to assessing relevant intention and action metrics is required to better understand how academics in LMIC are performing compared to their counterparts in HIC.

In this regard, this review found that the ‘Behaviour’ (action) theme was the next most popular amongst the articles reviewed, with collaboration and networking identified as significant activities undertaken by entrepreneurial academics in LMIC HEI. Furthermore, most articles identified intellectual property patenting, licencing, and spin-off as typical entrepreneurial actions in the HEI setting, with few recognising the expanded role of the engaged HEI beyond this narrow definition.

The ‘Characteristics’ (attributes) theme ranked third in article coverage, with entrepreneurial orientation being identified as most significant. Industry experience and business acumen was also identified as a significant factor that directly influences entrepreneurial intention, and such business acumen is shaped by an individual’s situational variances.

‘Barriers’ attracted significantly less coverage than the other three themes. In the main the obverse of ‘Enabler’ and ‘Characteristics’ factors were identified as barriers. One study identified crime as a significant barrier to entrepreneurial action in LMIC, a challenge generally not experienced in HIC [Guerrero & Urbano, Citation2017].

Future research into HEI entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial academics in LMIC settings is proposed using intention-based models as a theoretical basis, to better understand the differences between HEI and LMIC HEI entrepreneurship. It is important that appropriate models are developed (or existing models refined) that better fit the LMIC environment and recognise the differences in entrepreneurial objectives and activities in resource-poor settings, as well as the resource constraints LMIC academics face. This will allow for more accurate assessment of HEI entrepreneurial activity being undertaken in LIMC settings, where HIC entrepreneurial objectives are not realistic or necessarily applicable.

Limitations

By limiting the searches to studies reported in English, this scoping review might have missed relevant studies published in other languages. Such literature might have added valuable perspectives from non-English speaking writers.

Conclusion

Characteristics such as innovation, creativity and futuristic thinking are related to academic entrepreneurship by influencing the attitudes which directly affect entrepreneurial action. Role integration between HEI and the industry or prior industrial work experience have been found to be one of the behaviours that might activate academic entrepreneurship in LMIC. Research of the positive or negative impact of enablers or barriers is required to guide academics in incorporating entrepreneurship as HEI engagement with society progresses. Importantly, there is a need for the development of LMIC relevant intention-based theoretical frameworks (or refinement of existing models) that recognise the resource-poor environments within which the LMIC HEI and their academics operate, and the role they are required to play in addressing the impoverished socio-economic circumstances within which they exist.

Acknowledgements

The support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence (CoE) in Human Development, grant number OPP2019-4IRHD-1, at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg in the Republic of South Africa towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not to be attributed to the CoE in Human Development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I, 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50(2), 179–211.

- Al-Bader, S, Daar, AS & Singer, PA, 2010. Science-based health innovation in Ghana: health entrepreneurs point the way to a new development path. BMC International Health and Human Rights 10(1), S2.

- Albats, E, Alexander, A, Cunningham, J & Miller, K, 2018. Entrepreneurial academics and academic entrepreneurs: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Technology Management 77(1/2/3), 9.

- Arksey, H & O’Malley, L, 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1), 19–32.

- Bandura, A, 1982. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist 37(2), 122–147.

- Behroozi, M, 2012. Survey on university role in preparation graduated students in to entrepreneurs universities towards a conceptual framework: Iran's perspective. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 46, 2414–2418.

- Belitski, M, Aginskaja, A & Marozau, R, 2019. Commercializing university research in transition economies: technology transfer offices or direct industrial funding? Research Policy 48(3), 601–615.

- Broström, A, Buenstorf, G & McKelvey, M, 2021. The knowledge economy, innovation and the new challenges to universities: introduction to the special issue. Innovation 23(2), 145–162.

- Cantu-Ortiz, FJ, Galeano, N, Mora-Castro, P & Fangmeyer, J Jr, 2017. Spreading academic entrepreneurship: made in Mexico. Business Horizons 60(4), 541–550.

- Chang, Y, Chen, M, Hua, M & Yang, P, 2006. Managing academic innovation in Taiwan: towards a ‘scientific–economic’ framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 73(2), 199–213.

- Covidence Software, 2020. https://www.covidence.org. Accessed 15 June 2020.

- Dabic, M, Gonzalez-Loureiro, M & Daim, T, 2015. Unraveling the attitudes on entrepreneurial universities: The case of Croatian and spanish universities. Technology in Society 42.

- Dalmarco G, Hulsink W & Blois GV, 2018. Creating entrepreneurial universities in an emerging economy: Evidence from Brazil. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 135, 99–111.

- Etzkowitz, H, 1983. Entrepreneurial scientists and entrepreneurial universities in American academic science. Minerva 21(2-3), 198–233.

- Etzkowitz, H, 2013. Anatomy of the entrepreneurial university. Social Science Information 52, 486–511.

- Fischer, BB, de Moraes, GHSM & Schaeffer, PR, 2019. Universities’ institutional settings and academic entrepreneurship: notes from a developing country. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 147, 243–252.

- Freitas, JS, Gonçalves, CA, Cheng, LC & Muniz, RM, 2013. Structuration aspects in academic spin-off emergence: A roadmap-based analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 80(6), 1162–1178.

- Goethner, M, Obschonka, M, Silbereisen, R & Cantner, U, 2012. Scientists’ transition to academic entrepreneurship: economic and psychological determinants. Journal of Economic Psychology 33, 628–641.

- Grünhagen, M & Volkmann, CK, 2014. Antecedents of academics’ entrepreneurial intentions - developing a people-oriented model for university entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 6(2), 179–200.

- Guerrero, M & Urbano, D, 2017. The impact of triple helix agents on entrepreneurial innovations’ performance: an inside look at enterprises located in an emerging economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 119, 294–309.

- Guo, F, Restubog, SLD, Cui, L, Zou, B & Choi, Y, 2019. What determines the entrepreneurial success of academics? navigating multiple social identities in the hybrid career of academic entrepreneurs. Journal of Vocational Behavior 112, 241–254.

- Gur, U, Oylumlu, IS & Kunday, O, 2017. Critical assessment of entrepreneurial and innovative universities index of Turkey: Future directions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 123, 161–168.

- Heng, LH, Rasli, AM & Senin, AA, 2012. Knowledge determinant in university commercialization: A case study of Malaysia public university. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 40, 251–257.

- Kafouros M, Wang C & Piperopoulos P, 2015. Academic collaborations and firm innovation performance in China: The role of region-specific institutions. Research Policy 44(3), 803–817.

- Krueger, N, 1993. The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of New venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 18(1), 5–21.

- Krueger, N, 2000. The cognitive infrastructure of opportunity emergence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 24(3), 5–24.

- Krueger, N, 2009. Entrepreneurial Intentions are dead: long live Entrepreneurial Intentions. In A Carsrud & M Brännback (Eds.), Understanding the entrepreneurial mind. International studies in entrepreneurship. Springer, New York, NY, 24.

- Krueger, N & Brazeal, DV, 1994. Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Iberoamerican Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 7(2), 201–226.

- Lubango, LM, 2015. The effect of co-inventors’ reputation and network ties on the diffusion of scientific and technical knowledge from academia to industry in South Africa. World Patent Information 43, 5–11.

- Lubango, LM & Pouris, A, 2007. Industry work experience and inventive capacity of South African academic researchers. Technovation 27(12), 788–796.

- Nkosi, T, Aboginije, A, Mashwama, N & Thwala, W, 2020. Harnessing Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) for improving poor universities infrastructure in developing countries-a review. Proceedings of the International conference on industrial engineering and operations Management dubai, UAE, March 10-12, 2020.

- Peters, M, Godfrey, C, McInerney, P, Soares, C, Khalil, H & Parker, D, 2015. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. In E Aromataris (Ed.), Ed. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers manual 2015. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide, SA, Australia, pp.3–24.

- Schwab, K, 2016. The fourth industrial revolution: what it means, how to respond. World Economic Forum 19–24.

- Shapero, A & Sokol, L, 1982. Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C Kent, D Sexton & K Vesper (Eds.), The encyclopedia of entrepreneurship. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 72–90.

- Sutter, C, Bruton, GD & Chen, J, 2019. Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. Journal of Business Venturing 34(1), 197–214.

- Thomas, E & Pugh, R, 2020. From ‘entrepreneurial’ to ‘engaged’ universities: social innovation for regional development in the global south. Regional Studies 54(12), 1631–1643.

- Vivarelli, M, 2012. Entrepreneurship in Advanced and Developing Countries: A Microeconomic Perspective- Discussion Paper No. 6513.

- World Bank Task Force on Higher Education in Developing Countries, 2000. Higher education in developing countries: peril and promise. World Bank (20182).