ABSTRACT

In Namibia, the commercialisation of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) is often promoted as a means to improve rural livelihoods, especially for vulnerable communities. This paper analysed how NTFP value chains are integrated into and contribute to the livelihoods of Khwe and !Xun San harvesters. Accordingly, the working conditions, employment and upgrading opportunities of the globally traded Devil's Claw were compared to those of regionally traded products, including Natal Oranges. A mixed-method approach was applied to collect data in Okongo Constituency and Bwabwata National Park. Findings revealed that while NTFPs contribute to the harvesters’ income generation, the income is insufficient to sustain their livelihoods. Interestingly, the results of both regional and global value chain integration do not lead to improved livelihoods. Further research is needed to analyse the synergies between the government, traditional and local authorities, NGOs, and other institutions in implementing laws that promote equitable sharing of benefits from NTFPs.

1. Introduction

The commodification of non-timber forest products has become widely promoted because of its potential to improve the livelihoods of disadvantaged indigenous or landless communities that are forest-dependent, especially in the Global South (Marshall et al., Citation2006; Chao, Citation2012; Martin et al., Citation2019). Of the global total, 1.14 billion (71.3%) people from low- to middle-income countries live in or around forests and they can derive some benefits from forest products (Newton et al., Citation2020). In Southern and East African countries, non-timber forest products (NTFPs) were valued between US$ 30 and US$ 180 million in 2001, far exceeding the national income from commercialised timber products (Mogaka et al., Citation2001). Mogaka et al. (Citation2001) reveal that this high return from NTFPs encouraged more than 90% of the countries in the region to improve their forest management through policies and legislation. In the 1990s, just after independence, the Namibian government adopted community-based forest management policies and legislation that have since been promoting the commodification of forest products for rural livelihood outcomes while monitoring the harvesting for conservation and sustainability purposes (Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry, Citation2001; Alden-Wily, Citation2003; Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Citation2010; Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, Citation2020). The government, together with civil society organisations, promote the just and equitable utilisation of forest products through conservancies, community forests, and to some extent, national parks, particularly for the San people who live under poor agricultural and socioeconomic conditions (Alden-Wily, Citation2003; Gibson & Oosthuysen, Citation2009; Brown & Haihambo, Citation2015; Hitchkock, Citation2019).

This paper evaluates the significance that the value of commodified NTFPs adds to the livelihoods of the Khwe and !Xun harvesters in Bwabwata National Park (BNP), as well as the !Xun harvesters in Okongo Constituency (hereafter Okongo). The Khwe and !Xun are two of the six sub-ethnic San groups that are found in Namibia. The total San population in Namibia is estimated to be under 38,000 (Dieckmann et al., Citation2014). Collectively, the San are the most vulnerable indigenous people in Namibia, with their level of poverty unmatched by that of any other ethnic group (Dieckmann et al., Citation2014; Amnesty International, Citation2021). The two groups were purposefully chosen for comparison based on their different levels of livelihood opportunities despite similar subsistence practices. For income, most of the !Xun households in Okongo rely on the government’s social grants for vulnerable children or pensioners, who receive 250 or 1,300 NADFootnote1 per month, respectively (Mouton & Dirkx, Citation2014; Petersen & Ngatjiheue, Citation2021). Whereas in BNP, only 16.9% of the working-age Khwe and !Xun population is employed with monthly incomes ranging from 1,370–4,571 NAD, plus pensioners and vulnerable children who receive social grants (Paksi & Pyhälä, Citation2018). The San, as harvesters, collect NTFPs such as Devil’s Claw, Natal Oranges, Manketti fruits, False Mopane seeds, Mobola fruits, wild honey, caterpillars, and Dioscorea tubers for commodification. Interestingly, two products are outstanding, namely, the Devil’s Claw and Natal Oranges. The Devil's Claw is mostly traded globally, hence integrated into global value chains, in contrast to the Natal Oranges, which reach regional markets and thus can be considered intergated into a regional value chain.

Therefore, this paper aims to compare and contrast the impacts of the two value chains in terms of their conduciveness to opportunities for employment and upgrading, as well as the working conditions for the San NTFP harvesters. The paper makes contributions to the dynamics of value chains of non-timber forest commodities from and in the Global South, where socioeconomic disparities are high, by examining the effects of regional and global value chain integration on indigenous and vulnerable communities’ livelihoods.

2. Commodifying NTFPs through global and regional value chains

The commodification of NTFPs is recognised as an effort to economically empower disadvantaged communities in the joint achievement of conservation and development goals (Neumann & Hirsch, Citation2000; Marshall et al., Citation2006). Since the late 1990s, the commodification of NTFPs has been given due consideration by national and international agencies; compared to timber production, NTFPs are expected to have fewer detrimental effects on the forest ecosystem (He, Citation2010). Moreover, global and regional markets have risen to create competition between local harvesters and external actors in value chains (Wollenberg, Citation1998). Value chains are productive activities that lead to the end-use of products or related services (Sturgeon, Citation2001:12). They can be described as a set of interdependent economic activities carried out by various actors in different strategic networks to better respond to consumer demand (Donovan et al., Citation2015). In principle, two types of value chains can be distinguished, namely, global value chains (GVCs) and regional value chains (RVCs).

GVCs are defined as ‘a nexus of interconnected functions and operations through which goods and services are produced, distributed, and consumed on a global basis’ (Kano et al., Citation2020:58). While the GVCs offer a global scope of trade patterns and governance structures (particularly institutional policies and conditions), they do not consider non-firm organisations such as non-government organisations, trade or labour unions, and other agencies as significant factors influencing the economic development outcomes in different parts of the world, especially at a local level (Hess & Yeung, Citation2006; Neilson et al., Citation2018). Therefore, in this paper, GVC is paired with the global production network (GPN), which is defined as an organisational arrangement comprising of interconnected economic and non-economic actors, coordinated by global lead firms, and producing goods or services across multiple markets across the globe (Coe & Yeung, Citation2015:1). The GPN in relevance to commodified forest products effectively analyses power relations, values and embedment processes involved in GVCs and the position of local actors, especially concerning value capture and enhancement from international markets (Murphy, Citation2012). The GPN approach contributes to understanding the patterns of unequal development of global value chains. Therefore, GPNs are critical for recognising possibilities and challenges in inter-organisational networks, such as conflicting demands and low pay (Coe & Yeun, Citation2015; Sydow et al., Citation2021). The GPN agro-forest studies of Sub-Saharan Africa show that despite increased product exports, working conditions, social protection, employment and wages continue to deteriorate in the region while the GVCs become profitless for smallholders (Gereffi & Luo, Citation2014; Goger et al., Citation2014).

RVCs are rapidly becoming key features of twenty-first-century globalisation and they are projected to expand in the future as there has been an intensification of the value-added in regional trade compared to global trade, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (UNCTAD, Citation2020; Pasquali et al., Citation2021). RVCs are made up of suppliers and lead firms operating in a common geographic area with shared national or regional identities. They can be fragmented and vertically specialised into local or national processing industries serving local or regional markets (Horner & Nadvi, Citation2018; UNCTAD, Citation2020; Pasquali et al., Citation2021). In the context of this paper, RVCs are inter-firm and lead firm trading networks that exist within a country or across neighbouring countries. RVCs are frequently described in the southern and eastern regions of Africa as the expansion of retailers across the region (such as SACU or SADC) and their influence and ability for suppliers and workers to economically and/or socially upgrade (Barrientos et al., Citation2016). The expansion of RVCs can be considered an opportunity for small producers to gain access to large-scale value chains (Goger et al., Citation2014). However, such expansions do not guarantee fair benefits, especially for indigenous communities. Mogotsi et al. (Citation2016) reveal that indigenous people tend to harvest forest resources for other local traders in exchange for petty cash, thereby generating less income compared to the traders. RVCs in Africa are routinely embedded in or shifting to GPNs, where trade, production and labour patterns involve leading international corporations that process and source forest products to meet the growing global demands (Barrientos et al., Citation2016; Wardell et al., Citation2021).

2.1. GVCs and RVCs’ potential livelihood impacts: The advantages and disadvantages for local communities

Since gaining momentum, GVCs and RVCs in the Global South have had a variety of development outcomes and trading barriers faced by actors in value chains (Horner, Citation2016; Horner & Nadvi, Citation2018). While some nations are advantageously increasing their specialisations in production through RVCs, the GVCs are equally growing in importance through intermediate trade or final products at the global level (De Backer et al., Citation2018). Consequently, it is important for researchers to critically evaluate RVCs’ and GPNs’ ultimate contributions to the advancement of understanding emerging aspects of trade and new geographies of development (Horner, Citation2016). Such an analysis not only offers researchers and policymakers opportunities to measure the value-added through trade but also identifies the contribution that each value chain makes to the final product (De Backer et al., Citation2018).

When it comes to the potentially positive effects of GVCs on the livelihoods of local and vulnerable producers such as NTFP harvesters, we address three main points (see ) : First, the GVC-linked firms are likely to create employment opportunities and regulate wages in developing economies, particularly with the growth of the export market (Shepherd & Stone, Citation2013). However, because employment growth is primarily driven by unskilled labour and lower wages, the opportunities do not guarantee sustainable livelihoods, which ‘comprise of the skills, assets (both material and social) and approaches that are used by individuals and communities to survive’ (UNDP, Citation2017:2). This means that GVCs’ participation does not directly result in producers upgrading to higher-paying jobs or improving their livelihoods (Goger et al., Citation2014). Second, because GVCs provide crucial positions for inter-firm coordination and governance configurations, they could positively influence value creation and capture at a local level (Coe and Yeung, Citation2015). The GPN framework presents partnership opportunities between the government, NGOs, research institutes and other agencies to enhance the livelihoods of smallholders by lobbying for incremental benefits (Shahidullah & Emdad, Citation2010; Pauls & Franz, Citation2013). Conversely, local value chain actors can only participate in a global network if they conform to the demands of transnational corporations, which often results in lead firms in the GPN being exploitative (Murphy, Citation2012; Krauss & Krishnan, Citation2021).

Last and more recently, the GPN framework has positively contributed to discussions about corporate ethics, fair trade and social responsibility, with a focus on labour conditions (Lamb et al., Citation2019). Lamb et al. (Citation2019) recognise that local actors in the GVCs of natural resources, unlike agriculture and manufacturing, often lack an international regulatory system for trade. Therefore, direct and indirect local actors connected to natural commodities are commonly neglected through their transformation and reassignment of value. To understand the GVCs’ livelihood impacts and sustainability, studies should prioritise a holistic bottom-up analysis of how economic, environmental, and social upgrading and downgrading outcomes affect the less powerful value chain actors, rather than how global lead firms affect these actors (Krauss & Krishnan, Citation2021).

Table 1. Potential livelihood impacts of GVCs.

In comparison, RVCs in the Global South could break the dependence on dominant and developed markets, capital and technologies in the Global North, thereby stimulating local development and higher participation while also encouraging internal specialisation and industrial diversification within the region (UNCTAD, Citation2020: 162). Functional and industrial upgrading provide opportunities to transition into new activities such as design, marketing, and branding, which opens the door to structural transformation (Horner, Citation2016). This creates new employment and skilled labour demands (See ), thus boosting efficiency and improving coordination and production integration in the region (Krishnan, Citation2018; Hulke & Revilla Diez, Citation2022). Despite the opportunities to diversify end markets, the demand for the acquisition of new skills increases the possibility of marginalisation due to the growth of stringent regional standards in RVCs, especially among producers (Krishnan, Citation2018). Furthermore, RVCs are more complex to establish in a country that attracts foreign and global investment in which it has a competitive advantage (UNCTAD, Citation2020). This implies that countries with limited RVCs are less likely to create lead firms for improved value capture in the country.

In Africa, the commodification of indigenous plants is often appropriated through research and development investments by western-based pharmaceutical corporations and other agents who rake in billions of dollars (Eyong, Citation2007). Until the early 2000s, the San and Khoi’s indigenous knowledge of Hoodia gorginii and Rooibos was appropriated (Amusan, Citation2016; Wynberg, Citation2017). White farmers in South Africa continue to export 93% of Rooibos (Wynberg, Citation2017). This means that the value gained from NTFPs is not captured by the providers of the knowledge. Vicol et al. (Citation2019) support the idea that RVCs through national markets are a substantial means to enhance value for local actors. To address the problem of regional market access for local and indigenous people, an effective innovation model is required to foster indigenous entrepreneurship and sustainable solutions based on indigenous knowledge in the lack of formal education (Onwuegbuzie, Citation2009).

Table 2. Potential livelihood impacts of RVC.

Moreover, while there appear to be no major differences in labour standards between GVCs and RVCs for smallholders and national firms, RVCs present an opportunity for learning to achieve international standards and safeguard sustainability (Kowalski et al., Citation2015). Meanwhile, working conditions and enabling rights, especially for indirect and low-skilled workers, are generally unsuitable across the RVCs and GVCs; specialised workers in the GVCs are compensated better than those in the RVCs (Pasquali, Citation2021). This was proven in a case study of regional and global embedded firms in Lesotho and Eswatini, where the working conditions in the GVCs were better than in the RVCs in terms of paid production bonuses, sick leave, maternity leave, and access to healthcare facilities (Pasquali, Citation2021). However, undesirable working conditions in RVCs, if reported, tend to be addressed by government inspections, policies and strategies more than in GVCs (Pasquali, Citation2021).

3. Data collection methods

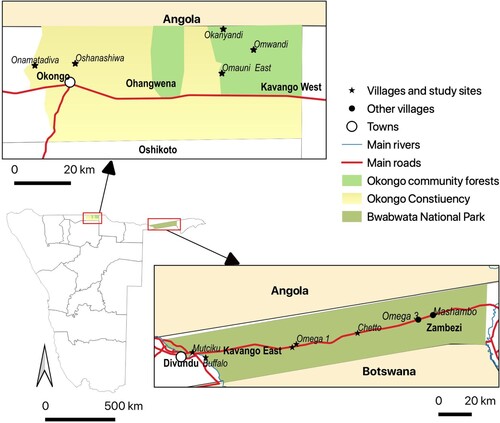

To better understand how NTFP integration in RVCs and GVCs affects the livelihoods of San harvesters, data were collected using a mixed-method approach through semi-structured interviews, participant observations, focus group discussions (FGDs), and statistics from secondary data. This approach was adopted from related studies on NTFP-dependent indigenous communities in Brazil and the Philippines, where mixed-methods were applied to determine the impact of NTFPs on livelihoods and to identify the relevant value chain structures, respectively (Morsello et al., Citation2012; Matias et al., Citation2018). As a result, 11 villages in BNP (Omega 1, Chetto, Mutciku, Buffalo, Mushangara and Mangarangandja) and Okongo (Okanyandi, Omwadi, Omauni East, Oshanashiwa and Onamatadiva) were purposively selected based on the availability of the Khwe or !Xun who are forest-dependent (see ). Using BNP and Okongo as case studies, we aimed to identify various NTFPs that are collected by the San harvesters in the areas as well as to understand the contributions they make to their households’ livelihoods. Therefore, 23 household interviews, 14 from BNP and 9 from Okongo, were conducted using the snowball sampling technique. This was done by identifying three San households that collect NTFPs for sale in both study areas and interviewing one informant in each household. Informants were then requested to recommend other San harvesters in the areas for interviews. The snowball sampling technique proved ideal for the San’s small and dispersed population, which was hard to reach without references, especially in Okongo. In addition, three FGDs with 10–15 participants each were held in Omega, Mutciku and Onamatadiva. FGDs were conducted to validate the effects of NTFP value chains on employment and upgrading opportunities as well as the working conditions of the harvesters, which are discussed in the theoretical section. FGDs also provided an in-depth understanding of harvesters’ experiences in the collection, use and trade of NTFPs.

Figure 1. Location of study sites in relation to the layout of Namibia. Source: Authors, data from Namibia Statistics Agency.

Furthermore, five experts were interviewed as key informants to understand the value of NTFPs and livelihood strategies in the studied communities. The key informants were identified from the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), the Office of the President’s Division of Marginalised Communities (OPDMC) in Okongo, and the Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC) in BNP.

Moreover, secondary data, including demographics of the target population as well as NTFPs’ purchasing data, were collected from relevant institutions and examined to support the empirical data collected, allowing data triangulation and effective analysis. Triangulation systematises and converts secondary data to maximise the depth of qualitative primary data analysis (Williams & Shepherd, Citation2017). The main data were collected between March 2021 and March 2022, with essential follow-up interviews continuing until September 2022.

Thematic and content analyses were used to identify the positive or negative impacts of the NTFPs from the transcribed interviews, using the research aim and value chain frameworks. Meanwhile, quantitative data were analysed using Microsoft Excel.

4. Description of the study sites

The Khwe and !Xun are two major San groups in the BNP and Okongo, respectively. In BNP, of the estimated 6,700 residents, the Khwe account for 80%, the Hambukushu 16%, and 4% account for the !Xun, Vagciricku, Vakwangali, Mafwe, Ovawambo and people from Angola (Jones & Dieckmann, Citation2014; Boden, Citation2020; Thomsen et al. Citation2021). All the residents of BNP strictly reside in the ‘Multiple Use Area’, where the Khwe and !Xun are primarily found in the settlements of Omega, Mutciku, Chetto, Omega 3 and Mashambo. Residents are prohibited from entering ‘Core Areas’, which are reserved for conservation and are patrolled by the Namibian Defence Force. Because there are few employment opportunities in the park, only a total of 108 (16.9%) of the working-age population are formally employed (Paksi & Pyhälä, Citation2018; Paksi, Citation2020).

Meanwhile, it is uncertain how many of the total 25,698 inhabitants in Okongo are !Xun, although the Ovawambo are the predominant ethnic group (NSA, Citation2014). Due to their nomadic lifestyle, it has been difficult to collect reliable statistics on the !Xun population in the constituency; many !Xun frequently move in and out of Okongo (OPDMC key informant, personal communication, 25 February 2022). In recognition of this challenge, the constituency is estimated to have 882 San households that are scattered throughout 38 villages, and of these, 721 households belong to !Xun families and only 161 households belong to the Hai||om (Constituency Office, Citation2022). In 2003, the National Planning Commission reported that the !Xun population in Okongo was about 1,052 (Mouton & Dirkx, Citation2014). Only three local San were formally employed in the Okongo (Mouton & Dirkx, Citation2014).

Most San residents in both Okongo and BNP are forced to rely on social grants, piece jobs, and seasonal jobs because of the lack of sustainable income-based livelihood outcomes.

5. The Khwe and !Xun harvesters of NTFPs for global and regional trade

Forests continue to be a significant source of food and medicine for San communities in Northern Namibia despite their adoption of subsistence farming from their neighbouring communities, but to a lesser extent. The San hold traditional knowledge of forest resources, which is often preferred over modern food and as a source of income (Jones & Dieckmann, Citation2014; Heim & Pyhälä, Citation2020). As a result, most Khwe and !Xun households in BNP and Okongo harvest NTFPs for household use as well as for sale.

5.1. Employment opportunities, upgrading and working conditions in harvesting Devils’ Claw for GVCs

Devil’s Claw is the common name for two medicinal plant species, Harpagophytum procumbens and H. zeyheri. In addition to its various traditional uses by the indigenous San, including as an analgesic and anti-inflammatory medicine, Devil's Claw has been commercialised to treat arthritis, tendonitis, renal inflammation, and heart disease (Stewart & Cole, Citation2005; Smithies, Citation2006). In BNP, where Devil’s Claw is also harvested, 72 residents, mostly Khwe, are formally employed by the Kyaramacan Association (KA), which is a community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) that was established in 2006 (KA informant, personal communication, 18 March 2022). The main role of the KA is to co-administer the sustainable harvesting of Devil’s Claw and tourism activities in the park together with the MEFT (KA, Citationn.d.). The KA receives money and other benefits from the MEFT for resource management as part of benefit-sharing. In 2011, the KA received 1.9 million NAD from the ministry, which was used to formally recruit the majority of the KA staff (Jones & Dieckmann, Citation2014). The Khwe and !Xun mainly receive the benefits, not only because they are collectively the largest group in BNP but also because they frequently adhere to the park's regulations (for example, not keeping cattle in the park), which the KA is required to maintain (IRDNC key informant, personal communication, 5 September 2022). According to the KA informants, most of the KA employees earn between 1,600 and 3,500 NAD per month, while the five senior employees earn around 7,000 NAD per month. In addition, there are 12 KA board members, who are elected every 3 years and receive 1,100 NAD per month. The average monthly income in the KA is one of the lowest in the formal job sectors that are available in BNP (Paksi, Citation2020). However, respondents who are employed stated that they live a better life than they did before employment. During the fieldwork, the differences between employed and unemployed Khwe and !Xun were observable in their households; those employed often had supplementary sources of livelihood, including raising some goats and chickens.

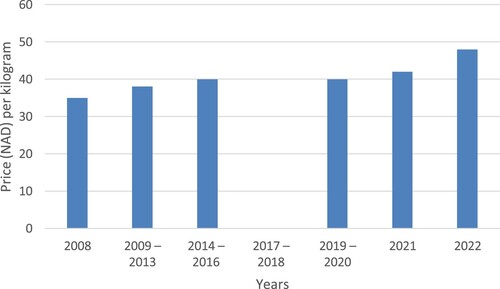

Within the GVCs of Devil's Claw, the KA is an important actor in the value chains. One of the KA's functions is to promote the sustainable harvesting of Devil's Claw for the global market by training and registering harvesters for traceability, and negotiating a concession agreement and price with one exclusive buyer (Jones & Dieckmann, Citation2014). According to the KA respondents, Khwe and !Xun make up the majority of the registered harvesters. Since 2008, registered harvesters have been collecting Devil’s Claw for ECOSO Dynamics (hereafter ECOSO), an exclusive buyer based on the concession agreement with the KA. The FGD participants indicated that annual quotas of 25 tonnes (25,000 kg) of Devil’s Claw are allocated by the MEFT for harvest in BNP. Before the 2008 concession agreement, harvesters were paid just between 8 and 16 NAD per kg of Devil's Claw. Harvesters collected Devil's Claw in an unsustainable manner, including harvesting the primary tubers needed for the plant's regrowth (MEFT, Citation2020). With ECOSO, the KA negotiated a price increase (see ) to 35 NAD per kg in 2008 and 40 NAD per kg in 2014 (KA informant, personal communication, 18 March 2022). Today, ECOSO is the largest trader and exporter of Devil’s Claw, accounting for 36% of the 3,278,612 kg exported between 2015 and 2018 from Namibia, mostly (93%) to Europe (Shigwedha, Citation2020). However, residents in BNP did not harvest or sell Devil’s Claw in 2017 and 2018, as harvesting was not allowed due to the intensive patrolling by the anti-poaching unit in the park. Consequently, the harvesters lost an important source of income that contributes to the well-being of a large number of households (Paksi & Pyhälä, Citation2018).

When harvesting resumed in BNP in 2019, the purchase price of Devil’s Claw remained at 40 NAD per kg until 2020. In 2019, only 619 of the 6700 BNP residents registered for harvesting and a total of 19,391 kg was sold, generating an income of 775,640 NAD for the harvesters (IRDNC, Citation2022; KA informant, personal communication, 5 September 2022). If we assume that all registered harvesters collected the allowed maximum of 100 kg per person, the average amount each harvester received would be 1,253 NAD. Meanwhile, no data was accessible to us regarding the quantity, value and income from Devil’s Claw for the year 2020. However, IRDNC (Citation2022) reported that the number of harvesters registered in 2020 increased to 1003. Interview respondents reported having earned, on average, 1,700 NAD in 2020. To understand how minimal the earnings are, we consider the minimum wage in Namibia's agricultural sector, which is currently 1,653 NAD per month or 19,836 NAD per year for unskilled employees working 45 hours per week (Matthys, Citation2021). Harvesters spent up to a month in the forest harvesting, cleaning, cutting, drying, and packing Devil’s Claw. All BNP participants said that their income was low considering the labour and costs they incurred to harvest the Devil's Claw. Harvesters often need to pay for transport to and from harvesting sites, the collection of the harvest, as well as food for their stay in the forest. Furthermore, camping and collecting the products in the park can be life-threatening when harvesters encounter potentially dangerous wild animals, including lions and elephants. In 2021, harvesters demanded a 5 NAD increase to reach a price of 45 NAD per kg of Devil’s Claw. When ECOSO did not meet their demand, harvesters went on strike and refused to harvest:

‘When ECOSO refused to increase the price to 45 NAD per kg, the KA management committee also refused to sign the purchasing agreement that allows them to purchase Devil’s Claw from here. They bought from conservancies in Tsumkwe at 50 NAD per kg but refused to increase our price. They even reward harvesters in Tsumkwe for excellent cutting, drying and packing of the products.’ -KA employee and harvester, Omega 1, BNP, 22 June 2021

Figure 2. Price per kilogramme for Devil’s Claw harvesters over different years. Source: Authors, data from the KA Office in Mutciku.

When it comes to economic and social upgrading, the Khwe and !Xun FGD participants indicated that the KA employees are seldom promoted. However, the association is supported by the MEFT, NGOs, and other agencies that offer yearly training on sustainable harvesting methods. The acquired training skills have so far not improved their income generation. One participant cited the lack of recognised Khwe traditional leadership as the biggest impediment to their improved economic development:

‘Governments, traders, researchers, NGOs, and other groups come here to absorb our ideas and use them more for their benefit.’ –Harvester, Omega 1, BNP, 23 June 2021.

5.2. Employment opportunities, upgrading and working conditions in harvesting Natal Oranges and other NTFPs for RVCs

During data collection, no Khwe or !Xun were formally employed in the local or regional NTFP-related sector. However, interview participants both in Okongo and BNP reported that they harvest and sell various NTFPs, which provide a small and seasonal income for their households. Products such as Natal Oranges, Manketti kernels, False Mopane seeds, wild honey and edible worms are commonly sold in BNP and Okongo, although in varying quantities; whereas, Mobola Plums are only available in BNP (see ). Collecting these NTFPs is one of, if not the, primary source of income for the !Xun who do not receive government social grants in Okongo. According to the FGD participants, this income is mostly earned from Natal Oranges and Manketti kernels, which provide some harvesters with up to 500 NAD per season. The demand for Natal Oranges, which are harvested and sold between August and December, has increased. Participants typically sell Natal Oranges for three Namibian dollars each, with some buyers subsequently reselling them to customers in other regions of Namibia. Today, Natal Oranges are sold for 11.25 NAD at Spar Supermarket, a regional retail store, in addition to Namibia's open markets.

Table 3. NTFPs harvested in Okongo and BNP by the Khwe and !Xun for local or regional trade.

On the other hand, participants in BNP indicated that they mostly sell False Mopane seeds, Mobola Plums and Manketti kernels. Harvesters in Mutciku, Chetto and Mushangara reside in an ecosystem with a variety of fruit/seed-bearing trees in abundance, which generates them additional income:

‘Sometimes, we can make up to 1800 NAD in one harvesting season. My family's only source of income is from harvesting NTFPs. I do not have an ID to register for the old-age social grants.’ -Harvester, Mushangara, BNP, 29 June 2021.

Due to the common practice of illegal fencing in Okongo, harvesters who live far from the community forests have limited access to forest resources. Such fencing further worsens poverty among the !Xun (Dieckmann & Dirkx, Citation2014). Participants in the FGD revealed that they are frequently restrained from harvesting NTFPs on the fenced-off land for their own income; instead, they are compelled to do so for those who fenced-off the land, often at a lower or no price. !Xun harvesters are sometimes paid in kind, in the form of food, second-hand clothes, or even a jug of alcohol (Mouton & Dirkx, Citation2014). Some harvesters travel to Omufitu Wekuta or Okongo community forests, or areas in Angola, to collect the products for sale. However, the community forests are more than 50 km from Okongo Town, where a market is located. This makes it costly for the !Xun harvesters to afford transportation to the market to generate better income from NTFPs.

In addition, no training is provided to those that harvest NTFPs for the local or regional market in Okongo and BNP (see ). Participants from Okongo, in particular, feel they are less empowered and lacking the capacity-building skills that are necessary to improve their products' value for better income. !Xun residents in the villages of Okongo considered themselves worse off, except for those of the Ekoka Resettlement Project, who are reported to be better off because they frequently receive training and support for various income-generating activities (Mouton & Dirkx, Citation2014).

Table 4. NTFPs’ livelihood impacts on the Khwe and !Xun San in BNP and Okongo.

6. Discussions

While the commercialisation of forest products is promoted to improve rural livelihoods and local incomes for vulnerable communities, the majority of !Xun and Khwe San harvesters in Okongo and BNP see little to no impact. This holds true regardless of the value chains in which the San harvesters participate, and as a result, neither GVCs nor RVCs substantially enhance the harvesters’ livelihoods. While the global trade of Devil’s Claw offers 72 formal jobs and training on sustainable harvesting practices, only a small number of Khwe and !Xun receive income from harvesting Devil’s Claw. The harvesters’ income does not transform their standard of living into a sustainable livelihood. The income for harvesters in BNP is 4,000 NAD lower compared to harvesters in the neighbouring Balyerwa Conservancy and Lubuta Community Forest, where there are no resource management structures, harvesting is unsustainable and communities have no socio-cultural connection to Devil’s Claw (Lavelle, Citation2019). Additionally, for NTFPs integrated into RVCs, factors including a lack of training in value enhancement, the products’ seasonality and distribution, as well as the inability to afford transportation, lead to low-income generation for San harvesters. These limitations have also been discussed in other studies (Amusa et al., Citation2017; Matias et al., Citation2018).

While harvesting NTFPs for commodification does not directly improve the livelihoods of the Khwe and !Xun San in BNP and Okongo, it may complement their other sources of income like piecework and social grants. Compared to !Xun in Okongo, the Khwe and !Xun in BNP appear to have better livelihood diversification options as there are employment opportunities in the tourism industry, community-based organisations and government organisations. However, formal employment is not available without educational qualifications, and the Khwe and!Xun populations still have low levels of education (Jones & Dieckmann, Citation2014). Employment opportunities for the Khwe and !Xun in BNP have been slightly improved by the KA, which is a unique CBNRM; however, such self-organised associations do not exist in communities that are located in the community forests of Okongo. This could explain why livelihood strategies established in BNP do not exist in Okongo communities, where the MEFT is also not essentially involved.

7. Conclusion

NTFPs have some positive impacts on the livelihoods of rural communities. However, the findings of this study revealed that the incomes generated from NTFPs by the Khwe and !Xun San harvesters in BNP and Okongo are unsatisfactory. Neither the GVCs of Devil’s Claws nor the RVCs of Natal Oranges and other NTFPs make a significant contribution to the livelihood outcomes of the harvesters. Of the 6700 BNP residents, only 72 are formally employed by the KA, of which the majority are Khwe. In Okongo, however, no !Xun resident works in an NTFP-related industry or earns an appropriate living from NTFP harvesting. In order to improve the bargaining positions of San harvesters, initiatives on value enhancement for vulnerable communities that allow them to make better incomes must be taken into account. Therefore, the study recommends that further studies be conducted on the role that policies and governance play in ensuring the fair and equitable sharing of benefits from indigenous knowledge-based forest commodities.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank MEFT for granting research permission for this study; the Khwe, !Xun and other research participants for sharing their experiences; Patricia Dinyando for her assistance with Khwedam to English translations; as well as the editor and anonymous reviewers for their insightful and largely valuable comments and suggestions that resulted in the improvement of our paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The exchange rate between the Namibian dollar and the US dollar was 17:1 at the time of conducting this study.

References

- Alden-Wily, L, 2003. Participatory forest management in Africa: an overview of progress and issues. https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF2016076325. Accessed 4 February 2022.

- Amnesty International, 2021. “We Don’t Feel Well Treated” Tuberculosis and the Indigenous San Peoples of Namibia. London.

- Amusa, T, Jimoh, S & Azeez, I, 2017. Socio-economic factors influencing marketing of non-timber forest products in tropical lowland rainforests of south-western Nigeria. Southern Forests: A Journal of Forest Science 79, 161–168.

- Amusan, L, 2016. Politics of biopiracy: An adventure into hoodia/xhoba patenting in Southern Africa. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 14(1), 103–109.

- Barrientos, S, Knorringa, P, Evers, B, Visser, M & Opondo, M, 2016. Shifting regional dynamics of global value chains: Implications for economic and social upgrading in African horticulture. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48(7), 1266–1283.

- Boden, G, 2020. Land and resource rights of the Khwe in Bwabwata National Park. In W Odendaal & W Werner (Eds.), Neither here nor there: Indigeneity, marginalisation and land rights in post-independence (pp. 229–254). Legal Assistance Center and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, Windhoek.

- Brown, A & Haihambo, CK, 2015. Developmental issues facing the San people of Namibia: Road to de-marginalization in formal education. In KC Chinsembu, A Cheikhyoussef & D Mumbengegwi (Eds.), Indigenous knowledge of Namibia (pp. 311–330). UNAM Press, Windhoek.

- Chao, S, 2012. Forest peoples: Numbers across the world. Moreton-in-Marsh. Forest Peoples Programme, United Kingdom.

- Coe, N & Yeung, HW, 2015. Global production networks: Theorising economic development in interconnected world. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- De Backer, K, De Lombaerde, P & Lapadre, L, 2018. Analyzing global and regional value chains. International Economics 153, 3–10.

- Dieckmann, U, Thiem, M & Hays, J. 2014. A brief profile of the San in Namibia and the San development initiatives. In U Dieckmann, M Thiem, E Dirkx & J Hays (Eds.), Scraping the pot: San in Namibia two decades after (pp. 21–36). Legal Assistance Center and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, Windhoek.

- Donovan, J, Franze, S, Cunha, M, Gyau, A & Mithöfer, D, 2015. Guides for value chain development: A comparative review. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies 5(1), 2–23.

- Eyong, CT, 2007. Indigenous knowledge and sustainable development in Africa: Case study on Central Africa. In EK Boon & L Hens (Eds.), Indigenous knowledge systems and sustainable development: Relevance for Africa (pp. 121–139). Kamla-Raj Enterprises, Delhi.

- Gereffi, G & Luo, X, 2014. Policy research working papers. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6847.

- Gibson, D & Oosthuysen, E, 2009. Between N! a† xam and tibi. A case study of tuberculosis and the Ju/'hoansi in the Tsumkwe region, Namibia. Anthropology Southern Africa 32(1-2), 27–36.

- Goger, A, Hull, A, Barrientos, S, Gereffi, G & Godfrey, S, 2014. Capturing the gains in Africa: Making the most of global value chain participation. Durham: Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness, Duke University.

- He, J, 2010. Globalised forest-products: Commodification of the Matsutake mushroom in Tibetan villages, Yunnan, southwest China. International Forestry Review 12, 27–37.

- Heim, A & Pyhälä, A, 2020. Changing food preferences among a former hunter-gatherer group in Namibia. Appetite 151, 104709.

- Hess, M & Yeung, HWC, 2006. Whither global production networks in economic geography? Past, present, and future. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38(7), 1193–1204.

- Hitchkock R, 2019. Foragers and food production in Africa: A cross-cultural and analytical perspective. World Journal of Agriculture and Soil Science 1(5), 1–10.

- Horner, R, 2016. A new economic geography of trade and investment? Governing south–southtrade, value chains and production networks. Territory, Politics, Governance 4(4), 400–20.

- Horner, R & Nadvi, K, 2018. Global value chains and the rise of the Global South: Unpacking twenty-first century polycentric trade. Global Networks 18(2), 207–237.

- Hulke, C & Revilla Diez, J, 2022. Understanding regional value chain evolution in peripheral areas through governance interactions – An institutional layering approach. Applied Geography 139, 102640.

- IRDNC (Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation), 2022. Management Fee payment 2019 - Kyaramacan Association. Zambezi Region and Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area.

- Jones, BTB & Dieckmann, U, 2014. Bwabwata national park. In U Dieckmann, M Thiem, E Dirkx & J Hays (Eds.), Scraping the pot: San in Namibia two decades after independence. Legal Assistance Center and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, Windhoek, 365–398.

- KA (Kyaramacan Association), n.d. About Us. KA, Bwabwata National Park. https://kyaramacan.wordpress.com/about/. Accessed 25 April 2022.

- Kano, L, Tsang, EW & Yeung, HWC, 2020. Global value chains: A review of the multi-disciplinary literature. Journal of International Business Studies 51(4), 577–622.

- Kowalski, P, Lopez Gonzalez, J, Ragoussis, A & Ugarte, C, 2015. Participation of developing countries in global value chains: implications for trade and trade-related policies. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 179, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Krauss, J & Krishnan, A, 2021. Global decisions versus local realities: Sustainability standards, priorities and upgrading dynamics in agricultural global production networks. Global Networks 22(1), 1–24.

- Krishnan, A, 2018. The origin and expansion of regional value chains: The case of Kenyan horticulture. Global Networks 18(2), 238–263.

- Lamb, V, Marschke, M & Rigg, J, 2019. Trading sand, undermining lives: Omitted livelihoods in the global trade in sand. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109(5), 1511–1528.

- Lavelle, JJ, 2019. Digging deeper for benefits: rural local governance and the livelihood and sustainability outcomes of devils claw (Harpagophytum spp.) harvesting in the Zambezi Region, Namibia. PhD thesis, University of Cape Town.

- Marshall, E, Schreckenberg, K & Newton, AC, 2006. Reviews. International Forestry Review 8(3), 368–369.

- Martin, A, Kebede, B, Gross-Camp, N, He, J, Inturias, M & Rodríguez, I, 2019. Fair ways to share benefits from community forests? How commodification is associated with reduced preference for equality and poverty alleviation. Environmental Research Letters 14(6), 0064002.

- Matias, DMS, Tambo, JA, Stellmacher, T, Borgemeister, C & Wehrden, H, 2018. Commercializing traditional non-timber forest products: An integrated value chain analysis of honey from giant honey bees in Palawan, Philippines. Forest Policy and Economics 97, 223–231.

- Matthys, D, 2021. The Minimum Wage for Farmworkers to be Increased by 18% in January. Namibia Economist. https://economist.com.na/66016/general-news/the-minimum-wage-for-farmworkers-to-be-increased-by-18-in-january/. Accessed 14 April 2022.

- MAWF (Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry), 2001. National forest policy. MAWF, Windhoek.

- MEFT (Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism), 2020. Integrated forest and wildlife management plan for the state forest in Zambezi region 2020-2030. MEFT, Windhoek.

- MET (Ministry of Environment and Tourism), 2010. National policy on the utilization of Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum) products. MET, Windhoek.

- Mogaka, H, Simons, G, Turpie, J, Emerton, L & Karanja, F, 2001. Economic aspects of community involvement in sustainable forest management in Eastern and Southern Africa (No. 8). IUCN, Nairobi.

- Mogotsi, I, Lendelvo, S, Angula, M & Nakanyala, J, 2016. Forest resource management and utilisation through a gendered lens in Namibia. Environment and Natural Resources Research 6(4), 79–90.

- Morsello C, Ruiz-Mallén I, Diaz MD & Reyes-García V, 2012. The effects of processing non-timber forest products and trade partnerships on people’s well-being and forest conservation in Amazonian societies. PLoS One 7(8), e43055.

- Mouton, R & Dirkx, E, 2014. Ohangwena region. In U Dieckmann, M Thiem, E Dirkx & J Hays (Eds.), Scraping the pot: San in Namibia two decades after independence. Legal Assistance Center and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, Windhoek, 233–288.

- Murphy, JT, 2012. Global production networks, relational proximity, and the sociospatial dynamics of market internationalization in Bolivia’s wood products sector. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102(1), 208–233.

- Neilson, J, Pritchard, B, Fold, N & Dwiartama, A, 2018. Lead firms in the cocoa–chocolate global production network: An assessment of the deductive capabilities of GPN 2.0. Economic Geography 94(4), 400–424.

- Neumann, RP & Hirsch, E, 2000. Commercialisation of non-timber forest products: Review and analysis of research. Center for International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia.

- Newton, P, Kinzer, A, Miller, DC, Oldekop, J & Agrawal, A, 2020. The number and spatial distribution of forest-proximate people globally. One Earth 3(3), 363–370.

- NSA (Namibia Statistics Agency), 2014. Ohangwena 2011 census regional profile. NSA, Windhoek.

- Okongo Constituency Office, 2022. List of San communities. Okongo Constituency Office, Ohangwena Regional Council.

- Onwuegbuzie, H, 2009. Integrating mainstream knowledge with indigenous knowledge: Towards a conceptual framework of the innovation process of indigenous entrepreneurs. SSRN 1841764, 1–10.

- Paksi, A, 2020. Rural development interventions_protected area management and formal education with the khwe San in bwabwata national park. PhD thesis. University of Helsinki.

- Paksi, A & Pyhälä, A, 2018. Socio-economic impacts of a national park on local indigenous livelihoods: The Case of the Bwabwata National Park in Namibia. Senri Ethnological Studies 99, 197–214.

- Pasquali, G, 2021. Labour conditions in regional versus global value chains: Insights from apparel firms in Lesotho and Eswatini (2021/145). UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Pasquali, G, Godfrey, S & Nadvi, K, 2021. Understanding regional value chains through the interaction of public and private governance: Insights from Southern Africa’s apparel sector. Journal of International Business Policy 4(3), 368–389.

- Pauls, T & Franz, M, 2013. Trading in the dark – The medicinal plants production network in Uttarakhand. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 34(2), 229–243.

- Petersen, S & Ngatjiheue, C, 2021. Over 770 000 Namibians depend on social grants. The Namibian. https://www.namibian.com.na/6213819/archive-read/Over-770-000-Namibians-depend–on-social-grants. Accessed on 29 August 2022.

- Shahidullah AKM & Emdad HC, 2010. Linking medicinal plant production with livelihood enhancement in Bangladesh: Implications of a vertically integrated value chain. The Journal of Transdisciplinary Environmental Studies 9(2), 1.

- Shepherd, B & Stone, S, 2013. Global production networks and employment: a developing country perspective. OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 154.

- Shigwedha, V, 2020. An assessment of Namibian Devil’s Claw export over a period of 4 years (2015-2018). MEFT, Windhoek.

- Smithies, SJ, 2006. Harpagophytum procumbens (Burch.) DC. ex Meisn. subsp. procumbens and subsp. transvaalense Ihlenf. & HEK Hartmann (Pedaliaceae).

- Stewart, KM & Cole, D, 2005. The commercial harvest of devil’s claw (Harpagophytum spp.) in Southern Africa: The devil’s in the details. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 100(3), 225–36.

- Sturgeon, T, 2001. How do we define value chains and production networks?. IDS Bulletin 32(3), 9–18.

- Sydow, J, Schüßler, E & Helfen, M, 2021. Managing global production networks: Towards social responsibility via inter-organizational reliability? economics–the relational view: Interdisciplinary contributions to an emerging field of research. Springer, Cham, CH.

- Thomsen, JM, Lendelvo, S, Coe, K & Rispel, M, 2021. Community perspectives of empowerment from trophy hunting tourism in Namibia’s Bwabwata National Park. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 30(1), 223–239.

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), 2020. World investment report 2020: International production beyond the pandemic. United Nations, New York.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2017. Guidance note: Application of the sustainable livelihoods framework in development projects. https://www.undp.org/latin-america/publications/guidance-note-application-sustainable-livelihoods-framework-development-projects [accessed 14 August 2022].

- Vicol, M, Fold, N, Pritchard, B & Neilson, J, 2019. Global production networks, regional development trajectories and smallholder livelihoods in the Global South. Journal of Economic Geography 19, 973–993.

- Wardell, DA, Tapsoba, A, Lovett, PN, Zida, M, Rousseau, K, Gautier, D, Elias, M & Bama, T, 2021. Shea (Vitellaria paradoxa C. F. Gaertn.) – the emergence of global production networks in Burkina Faso, 1960–2021 1. International Forestry Review 23(4), 534–561.

- Williams, TA & Shepherd, DA, 2017. Mixed method social network analysis, Organizational Research Methods, 20(2) 268-298.

- Wollenberg, E & Ingles, I, 1998. Incomes from the forest. Methods for the development and conservation of forest products for local communities. Center for International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia.

- Wynberg, R, 2017. Making sense of access and benefit sharing in the rooibos industry: Towards a holistic, just and sustainable framing. South African Journal of Botany 110, 39–51.