ABSTRACT

White monopoly capital’ (WMC) has become one of the most ubiquitous terms in the South African political lexicon, bolstered by a re-energised nationalist movement. Its rise has been the occasion for a welcome debate on the changing dimensions of race, power, and control in the capitalist class. However, that debate has remained polarised between a camp that has been largely dismissive of the very possibility of a racial power bloc and one that sees it as a self-evident reality. By posing the question of whether WMC is a ‘useful’ category of analysis, this article seeks to take a more historical and empirical approach to the issue. It argues that WMC analyses implicitly overstate both the extent of white control and the extent of racial division in the elite. Yet, it argues, race still has important impacts on elite politics both within the corporate sphere and across the wider field of business. It concludes by sketching avenues of research on the politics of race, control, and cohesion in the South African elite.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

‘White monopoly capital’ (WMC) – stodgy piece of Marxist jargon that it is – would make an unlikely candidate for a viral political meme in most parts of the world. But South Africa is exceptional in many ways and this was clearly well understood by Bell Pottinger, the infamous marketing firm most directly responsible for embedding the term in the country’s political lexicon. The promotion of ‘WMC’ by Pottinger was part of a public relations endeavour with the Guptas – a family of Indian businesspeople at the heart of vast rent-extraction networks during Jacob Zuma’s administration (2009–18). Pottinger entered the scene as the lid was being partially lifted on ‘state capture’ and ever more brazen tales of corruption were breaking weekly in the press. Their strategy was to portray this as part of a campaign waged by recalcitrant white elites angered by the ‘radical economic transformation’ the Guptas were helping to orchestrate. It’s not clear whether ‘WMC’ was their invention or if they lifted it from old anti-Apartheid pamphlets – it appears occasionally in struggle-era Leftist literature but was never widely known. That quickly changed. Propelled by wily marketing and legions of Twitter trolls, the term exploded into the public discourse. By 2017 it was crowned as one of the ‘words of the year’ alongside ‘state capture’ and ‘blesser’ by the Pan South Africa Language Board.

Its memetic success is not hard to explain. Boosterism for the term went far beyond Bell Pottinger. Beresford et al. (Citation2023) offer a fascinating genealogy of its initial diffusion through social media networks, pushed forward by a ‘seemingly contradictory elite network of international capitalists, leading figures within the ruling party [and] radical leftist social movements’. This campaign no doubt drew in a much wider array of partisan actors rooted in the ‘informal economies’ of the Gupta-Zuma nexus who shared an antipathy to large-scale capital (Von Holdt, Citation2019). But the WMC moment wasn’t entirely astro-turfed. The terms wide resonance cleared owed partly to its alignment with commonsensical truths of post-Apartheid society, above all the persisting concentration of economic assets in the hands of white people. Deep racial mistrust fuelled its momentum. Large majorities of South Africans regularly tell surveyors that they believe members of other races ‘tend to exclude members of my group from positions of power and responsibility’ (HSRC, Citation2017). Before Pottinger’s intervention, the existence of a revanchist elite hoarding economic resources was already common cause for wide swathes of the public.

For Pottinger the victory proved pyrrhic – its campaign stirred powerful enemies, ironically, in the Johannesburg-London business community, which conspired to ensure its swift demise. But WMC outlived its maker, becoming firmly entrenched in public discourse. It gained a circulation far beyond the elite groupings which first sponsored it. Politicians, activists, journalists, and scholars still frequently employ the term – often as shorthand, sometimes as slur and occasionally as sociological category.

It’s rise created the occasion for a welcome public debate on the racial politics of the elite, mostly drawing in interlocutors associated with the Marxist Left (Cronin & Mashilo, Citation2017; Lehulere, Citation2017; Malikane, Citation2017; Patel, Citation2017; Southall, Citation2017; Desai, Citation2018; Ford, Citation2018; Rudin, Citation2018; Aboobaker, Citation2019). The Wits academic Chris Malikane (Citation2017) offered an analysis of the political conjuncture in South Africa which aligned with the Zuma faction in seeing WMC as the hegemonic force in the country and the principal barrier to progressive change. He argued for working class forces to support ‘tenderpreneurial’ capital in its fight with big business. However, like others who favour the term (Lehulere, Citation2017; Lepuru, Citation2023), he didn’t do much to motivate for its sociological accuracy, or to defend it against obvious objections. The fact that big corporations are ‘largely’ or ‘overwhelmingly’ white seemed to be enough for early proponents to accept its validity. Black business people who are prominent in the corporate sector are dismissed as ‘junior partners’. Malikane labels them a ‘credit-based’ fraction of capital, implicating them in a dependency relationship with dominant white capitalists.

His views have drawn harsh criticism from other sectors of the Left. Communist party intellectuals Jeremy Cronin and Alex Mashilo (Citation2017) accuse him of ‘Gupterizing’ Marxism. With good cause, they point out his failure to demonstrate how workers would gain from throwing their lot in with a ‘parasitic’ bourgeoisie, whatever its antagonism towards other elites. Malikane’s political conclusions are the focus of their critique. Their opposition to WMC is more theoretical. ‘Capital’, they say, deferring to Marx, ‘knows neither colour, nor creed nor sexual orientation’. It may be divided into various strata and fractions but these ‘all ultimately stand and fall according to the laws of capital accumulation’, which today are ‘neo-liberal laws’. The point seems neither true nor entirely relevant. Neoliberalism is inscribed in the institutions of capitalism, not its laws. Even where it’s dominant, it's contested – one can always find segments of business that espouse anti-neoliberal policies – stronger financial regulation, or vertical industrial policies, for example. And while the actual laws of capital accumulation might unite capitalists horizontally, as a class, they are left divided vertically. To proscribe in theory the possibility that race could be a faultline of that division is an odd position for a South African Marxist to hold. Segmentation along both racial and ethnic lines has been an enduring feature of the domestic business system since its inception (O’Meara, Citation1983).

In general, the debate on WMC has focused on airy theoretical disputes while having little to say about the actual dynamics of control and contestation in the corporate sector. Scholarly work has had little to offer it, reflecting the general paucity of research on the South African elite sphere. Post-Apartheid sociologists have tended overwhelmingly to study ‘downwards’, a pattern that's largely continued amidst a resurgence in elite studies globally. One exception is Roger Southall (Citation2014), who’s written field-defining works on both middle and upper classes. In his brief foray into the debate, Southall (Citation2017) calls WMC ‘good politics, bad sociology, worse economics’. He acknowledges its utility for populist agitation. But, he argues, it rests on an understanding of power and control in the economy that is too ‘crude [and] simplistic’. This results in misguided policy prescriptions – nationalisation by a failing state. His intervention, however, is too short to really establish these points. Empirically, he doesn't move the issue much past a dispute on the precise extent of black stock ownership – which I’ll argue is a misleading datapoint on which to fixate.Footnote1

This essay seeks to supply some of the empirics that have so far been missing in the debate around WMC. It uses that debate as a chance to survey dynamics of ownership and control and of interest formation in the corporate economy. I draw on historical institutionalist theories in seeking to understand how configurations of control were altered during the liberal-democratic transition, emphasising how domestic political forces interacted with global pressures to shape emergent corporate forms (Mizruchi & Schwartz, Citation1987; Padayachee, Citation2013). I also draw on contemporary Marxian class theory to understand how interests and ideology and race shape elite social action (Chibber, Citation2022). In trying to better marshall the existing evidence towards an understanding racial politics in the elite, this paper also tries to highlight gaps in that evidence and to sketch out avenues for further research.

To pose the question of whether WMC is a useful sociological category we have to first define it. In its most common usage, WMC refers to a ‘fraction’ or a ‘bloc’ of capital. This I take to mean a coalition of capitalist interests that is defined by both durability and seniority. By durability, I mean that the coalition is stable and long lasting. It represents alignment around a long-term program for political-economic change, not simply fleeting, particularistic demands. By seniority, I mean that the coalition is given precedence over other affiliations. Any particular capitalist or firm might be partner to an array of cross-cutting alliances: its bloc is the group with which it is most consistently aligned and which most consistently guides its political endeavours. Both durability and seniority are a reflection of the fact that the common preferences and issues underlying the coalition are regarded as highly salient by its members. Most proponents of the term regard WMC to be the hegemonic or dominant bloc in South Africa, but I don’t take this to be intrinsic to the term.

WMC will be a useful category if a white monopoly bloc exists. We can prove the existence of such a bloc if we can show three things. Firstly (1), that there is some large enough subset of firms in which white people monopolise power. This needn’t be a total monopoly, but one sufficient as to allow them to impose their own racial prerogatives over the decision-making process. Secondly (2), we need to show that these firms are united in a ‘bloc’. Thirdly (3), we would need to show that whiteness is decisive for this bloc – i.e. that its racial character is significant for understanding how it acts politically and economically. If (1) and (2) are true but not (3) then WMC would be descriptively accurate but not explanatorily relevant. That would be insufficient by any standard of ‘usefulness’. Belgium is almost certainly dominated by a white-controlled bloc of large-scale firms but no one calls this a ‘white monopoly’ bloc because its whiteness is not immediately relevant to the outcomes which the concept of a bloc seeks to explain. That’s not to say that its whiteness, or the whiteness of the South African corporate sector, isn't relevant for a host of other outcomes. But concepts should be built with theories in mind, and the theory we’re concerned with is one that seeks to explain the high-level political and economic behaviour of capitalist units.

Below I focus on tasks (1) and (3) and show that neither can succeed. Whites might be disproportionately represented in positions of influence but corporate power is nevertheless highly diversified. The debate on WMC misses this because it focuses on ownership. But directorship, not ownership, is the primary locus of control in the corporate sector. Around two-fifths of corporate directors are black. Corporate boards, moreover, are generally integrated, meaning that there are few firms in which whites are in a position to monopolise power. They could do so only if they succeed in walking over or hoodwinking their black counterparts. I pushback on several recent accounts which, while not employing the term, follow the spirit of a WMC analysis in viewing Black Economic Empowerment largely as a cosmetic affair that effectuated the appearance of transformation while leaving historic white elites firmly in control (Mpofu-Walsh, Citation2021; Habiyaremye, Citation2022; Majavu, Citation2023). Such accounts erase the agency of black elites and elide the obvious power resources they accrued through the ANC’s domination of the state.

A wrinkle here is the possibility that WMC exists not as a coalition of firms but as a power structure in the economic elite. The notion of a ‘Stellenbosch mafia’ purports this (Du Toit, Citation2019). Here we are more in the dark in terms of hard evidence, because the elite is so understudied outside formal institutions. Still, nothing suggests that such a formation is likely. The best reasons to doubt the existence of a Stellenbosch Mafia are also the best reasons to doubt the existence of WMC – namely that point (3) above cannot be sustained. Even if we could identify a bloc of firms capacitated to prioritise a racial agenda, it’s unlikely that they would actually do so because it's not clear what such an agenda would entail. Likewise, individual elites are unlikely to launch racial conspiracies because it's not clear what they would gain from doing so. The contemporary racial order doesn’t configure corporate elite interests in a deeply antagonistic way. Any major racial division within the corporate sector would therefore have to be purely ideological in nature. I argue that elite political action is governed by a form of materialist primacy, which makes such an outcome extremely unlikely.

There is no WMC because race isn’t a primary cleavage within the corporate elite. This is very different to saying that black and white elites are politically homogeneous. Surveys would almost certainly reveal some measure of distance between the two, on both political and economic questions. This results not just from cultural factors, but from the fact that the two groups are positioned differently in relation to political capital and economic assets. I differ from certain Marxist interlocutors in the debate in insisting that these disparities might matter for a range of outcomes, even if they don’t portend competing elite ‘blocs’. Social distance might also impact the ability of the corporate elite to achieve cohesion. Moreover, bigger cleavages do appear within the wider field of business that are racialised, if not neatly racial. Corporate elites and smaller ‘tenderpreneurial’ factions of business have come to blows over Black Economic Empowerment in recent years (Steyn, Citation2011). All of these issues are seriously understudied however. This essay concludes with a discussion of pathways for research on race and the South African elite, getting beyond the cul-de-sac of WMC.

A word on terminology: for the purposes of this paper I follow a common tradition of the anti-apartheid movement in defining all previously oppressed groups – everyone who is not white – as ‘black’.

2. Ownership and control since democracy

White monopoly capital may or may not exist but white capitalists certainly exist in abundance. Despite making up less than 8 percent of the population, most large-scale capitalists in South Africa, however defined, are white. For certain proponents of WMC this is enough to justify the term. But if it’s to be anything more than a shibboleth for stalled transformation then clearly more is needed. We have to show firstly that white over-representation also translates into control over the relevant levers of power. Capital, afterall, is a collective agent. Aside from a few exceptions, decision-making in large firms is partitioned between managers, boards of directors and shareholders – each themselves collective bodies. Governance occurs through a political process that plays out within and between each of these centres of power and through negotiations and disputes with other stakeholders and external actors. WMC theory assumes that whites are able to resolve this process in their favour, such that particularistic racial preferences can be served through the way the firm deploys influence and resources. On this basis, a larger collective of corporations – a bloc – can coalesce around a racial agenda. The burden is on them to show this is true.

So far they have not. At an empirical level debate has largely circled around a single, highly disputed datapoint: the extent of black ownership of the JSE. Some figures put this at as low as 3%. The more reputable sources estimate it at around 10% (2017 figure), most of this ‘indirect’ – mediated through financial institutions (Thomas, Citation2017). That's as a proportion of the whole, but it's not actually clear what the denominator of the term should be, since around half of the JSE is foreign owned. Whatever the real figure is, on its own it tells us more or less nothing about power and control, however useful it might be for other outcomes. For ownership to be informative for our purposes we would firstly have to know how it’s distributed and mediated. A 10% overall ownership share could mean that black people own a nominal share in a wide variety of companies, or could it mean that they own a controlling stake in a selection of highly influential firms. Whichever is true, it wouldn’t resolve the issue because control is not reducible to ownership in the modern economy.

This, however, is a somewhat recent truth. For most of the twentieth Century, a ‘Big Man’ form of capitalism prevailed in South Africa. Economic power was hugely concentrated at the firm level: a handful of business groups – the ‘Minerals Energy Complex’ overwhelmingly dominated economic activity (Fine & Rustomjee, Citation1996). Internally, conglomerate power was highly personalised. Formal authority typically rested with an individual or family who projected control over the whole group through pyramidal ownership structures and interlocking directorates. Reddy (Citation2023) finds that as late as 1993, MEC titans like Donald Gordon and Basil Hersov were sitting on upwards of 11 boards. These were largely pliant, stuffed with loyal employees and dedicated mostly to rubber stamping the decisions of ‘Big Men’ who typically served jointly as Chair and CEO. The wider apparatus of control within the MEC resided in social ‘groups sharing common social, cultural, and linguistic norms, bound together outside the boardrooms thorough old school, club, societal, political, church, sports and other such networks, including secret societies (eg Broederbond, Freemasons)’ (Padayachee, Citation2013: 263) ‘Gentlemen’s agreements’ and personal relationships rather than primarily formal structures oiled the channels of coordination within this apparatus, which was densely interlocked across the different business groups (Padayachee, Citation2013; Reddy, Citation2023). This was the classical age of white monopoly capital.

But all this changed with democracy. Over the transition period, corporate governance and ownership structures in South Africa underwent a rapid process of modernisation, which brought them more into line with dominant Anglo-Saxon institutional models. This was a result initially of two principal factors: pressure from the new government to dismantle concentrated bases of economic power in order to make room for emergent black capital; and a desire on behalf of big corporates themselves to renovate governance systems in preparation for internationalisation (Ashman et al., Citation2011; Makhaya & Roberts, Citation2013). A third, institutional, factor took hold after early reforms which included capital market liberalisation. Foreign institutional investors entered the domestic market rapidly, drawn by its depth and sophistication and by long standing connections between the Johannesburg and London business communities. They built up large portfolios as MEC groups were unbundled, and used their influence to accelerate reforms. South Africa vaulted from an individualised robber baron style of capitalism to a shareholder oriented one, leapfrogging the managerialist phase through which most other liberal economies had transitioned. Block holding by institutional investors replaced family ownership. Surviving firms were winnowed down to their ‘core competencies’ and rapidly globalised. Shareholder value-based governance systems were popularised, which meant a rolling back of ‘Big Man’ influence and greater power vested in boards dominated by outsider directors.

The South African business system today is, like anywhere, variegated but on balance it resembles a modal liberalised economy. Formal control rests primarily with institutional investors. The latest data shows that only 15 out of 230 SA-domiciled, JSE-listed firms were without a single significant blockholder (10% holding or more). Almost half had at least two. However, institutions vary enormously in the capacities, constraints, and incentives they face for exercising their prerogative power. They are not in any way equivalent to family owners – only in exceptional cases do they engage in direct, full spectrum oversight over the management of their subsidiaries. To the extent that some institutions are active stewards their influence usually operates through ‘limit determination’ – establishing the parameters in which managers operate and intervening only rarely to enforce those parameters. This means, in essence, ensuring broad compliance with shareholder value maximisation principles and occasionally ESG objectives.Footnote2

The politics of the modern liberalised firm are therefore complex. Power is partitioned between the boardroom, the C-suite and the AGM but not fixed in place – its precise locus will vary depending on the matter at hand. Either way, however, it rests overwhelmingly in the hands not of individual owners but of directorial collectives – be they of institutional investors or of JSE firms themselves. This system itself is the first bulwark against the formation of a racial bloc in the elite insofar as it represents a de-personalisation of power within the corporate system and with it a narrowing of the scope for ideology to motivate political action. By institutionalising, bureaucratising, and subdividing decision making, shareholder capitalism promotes a narrower form of economic-rationality which will countervail against racial factionalisation given shared material interests between black and white elites.

The issue is seriously understudied, but in relation to political questions, primary control over JSE firms most likely rests with the directorship (encompassing management). Investors act to ensure that those activities are congruent with value maximising imperatives, though it's not clear how assiduously they do so. US investors seemed to have dramatically intensified their political stewardship between 2010 and 2016 with the percentage of major corporations reporting regular board oversight of political expenditures increasing almost threefold to 65 percent (Bonica, Citation2016: 389). It’s not yet clear why this happened and we have no comparable data for South Africa so are limited in what we can say about the domestic case. Ultimately however, the nuances are not important for us since it will turn out that neither major corporations nor the investors that nominally control them are white dominated. In contrast to what many would expect, power is in fact more diversified at the top of the economic chain than it is lower down. This is probably a reflection of the greater institutional, regulatory, and political pressure for transformation to which larger firms are subject.

3. Are white people in control?

Let’s start with ‘ownership’ (institutional investors). For this analysis, I assembled a dataset consisting of the universe of large SA-domiciled shareholders of JSE-listed, SA-domiciled corporations from the online portal of Who Owns Whom, excluding government entities, SOEs, and individuals. WOW’s database is likely patchy for small investors, but near complete for entities with moderate and larger holdings (> 1%). Two variables are of primary interest to us. Firstly and most importantly, the percentage of black directors on an investor’s board. Secondly, it’s BEE ‘management and control’ score which is a composite index reflecting the extent of black participation in upper and middle management and directorship. Details of how this is calculated are provided in Appendix 1. I also report percentage black ownership as recorded on an investors BEE scorecard. Great caution needs to be applied to this figure however: it’s likely to deviate significantly from actual black ownership due to technicalities in how it's calculated – a result of the ‘political compromises’ made during the drafting of BEE codes according to Gqubule (Citation2021). Finally, I look at investors’ overall BEE rating.

Row 1 of the provides mean and medians of these variables for the whole dataset. The numbers roundly confute any notion of white monopolisation. The boards of large investors are 37.06% black on average and those firms have an average of 40.16% (BEE) black ownership. They scored an average of 58.48% of the target on ‘management and control’ on their BEE scorecards, giving an average score of 11.11 and suggesting extensive diversification of middle and upper management (see Appendix 1).

Table 1. Black empowerment in SA investors.

However, missing data presents a big problem since most investors are private companies, which do not report or do not have BEE scorecards. We have information on at least one statistic for only around a third of the 613 investors in the dataset. This could upwardly bias results due to non-random reporting – investors with better BEE scores are more likely to disclose. However, this is much less of a problem among larger institutional investors. It’s really here that we ought to be concentrating our analysis due to vast scale asymmetries – the largest ten percent of investors controlled 89.26% of the total JSE value held by South African entities. In the 2nd to 4th rows of , I present diversification figures for the largest 30 investors defined in different ways. Firstly, as the firms with the largest portfolios in rand value – measured by multiplying their holding in each subsidiary by the subsidiary’s market capitalisation and then aggregating this for the investor’s entire portfolio. Secondly, as the firms with the largest turnover. And thirdly, as the 30 firms with the largest number of controlling stakes, defined as a holding size of 10% or more.

Power and control in big investors are generally more diversified than it is among shareholders in general. With the partial exception of ownership scores, large investors have higher rates of black participation than the full sample. This finding is robust to altering sampling sizes and to restricting the sample to investors with a portfolio size of 5 or more – which eliminates holding companies. Appendix 2 lists the full set of firms and their characteristics for each of these samples. Holes remain. Just eyeballing the lists, however, mitigates bias concerns – many of the investors with missing information are well known, black-controlled entities like Motsepe’s Ubuntu-Ubuntu. Even if firms with missing information were exclusively white, i.e. had a zero score on all diversity measures, this wouldn’t change the overall conclusion – that power is substantially diversified among big owners.

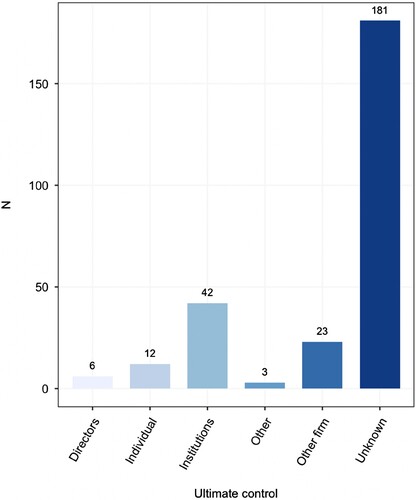

Next, we look at JSE firms themselves. is constructed from WOW’s attempts to establish ultimate control by following intermediation chains to their endpoint. It shows the difficulty of this task today. The vast majority of firms had no single identifiable centre of control. In most of these cases, it’s likely control is distributed between institutional investors and directors as described above. Institutions dominate among known cases. In , I report the same diversity statistics for JSE firms, emphasising board diversification. Since we’re now dealing with listed firms, data is far more complete. Again, the figures explode any notion of white monopolisation. Black directors comprised over 37% of the total in 2023. Diversification is once again correlated with power and size, with bigger firms recording higher average empowerment figures. Directorship among the largest 30 SA firms by market capitalisation was 45.6% black. Reddy (Citation2023) also looks at the distribution of racial groups across boards. Using methods from neighbourhood studies he finds that boards are generally well integrated. We can therefore dismiss the possibility that black directorship is heavily concentrated in certain firms, leaving white people in exclusive control of others, which might be cobbled into a racial bloc. In fact power is diversified more or less across the board. Only 35 of 230 firms had fewer than 15% black directors in 2023.

Table 2. Black empowerment in JSE-listed SA firms.

Although comprising the majority of the capitalist elite, white people are therefore obliged to share power in collective decision making bodies with a substantial cohort of black capitalists. This would appear to make it more or less impossible for a racial agenda to be actualised through corporate institutions. There's an analogy to be drawn here with the US where, as Bonica (Citation2016) shows, corporate boards are normally politically heterogenous, containing both Republican and Democrat elites, possibly by design. Consequently, individual directors and corporations exhibit very different patterns of political behaviour as registered through donations. The former tend to be consistently partisan in their largesse. Corporate PACs, in contrast, follow an investor model of giving, donating to candidates from both major parties, avoiding heavily contested elections and favouring incumbents. In effect, the bifurcation of decision-making power neutralises firm partisanship. In South Africa, racial bifurcation will neutralise identity-driven politics.

The only way to resist this conclusion is to assume massive power asymmetries between white and black elites. This assumption does indeed seem to be commonplace in WMC theories, which must still account for high-profile black executives, even if they downplay the extent of black corporate leadership. Those theories tend to dismiss black directors as ‘tokens’ or ‘fronts’ for Black Economic Empowerment, who provide a patina of transformation while allowing white people to continue to hoard power. In a similar vein, Habiyaremye (Citation2022) argues that black elites fell victim to ‘epistemic violence’ and were indoctrinated into a foreign, ‘Western’ culture which, presumably, domesticated them to the extant power structure. Such views have never been backed by direct evidence however. Their appeal stems from their consistency with a more general interpretation of post-Apartheid politics which ascribes huge power to incumbent white elites in steering historical outcomes. While elites are held to have successfully overseen the transition to a neo-colonial order a ‘new Apartheid’ in part through their success in co-opting and mollifying black leadership (Mpofu-Walsh, Citation2021; Majavu, Citation2023).

Looking backwards, it’s not too hard to understand why some assign whites special powers. The extent to which they were able safeguard their own interests, conceding virtually nothing to well-founded demands for redistribution, was remarkable. This rested on the ANC’s sudden conversion from redistributionist social democracy to free market ideas – in which domestic corporates were ultimately the key actors (Khan & Mohamed, Citation2023). But to see all of this as foreordained is a mistake. The challenges democratisation posed to large-scale capital were huge. Demographic factors meant that historic white parties would be locked out of government. State power passed into a monopoly of the ANC, allied to the Communist Party and to one of the most militant labour movements in the world, which raised demands for ‘radical reform’ as an alternative to liberalisation. Although optics were no doubt part of the equation, black elites with whom white capital sought to forge allegiances were never intended to provide simply a fig leaf of transformation. White capital sought genuine partners, with real influence who could act as effective interlocutors with the new political elite (Tangri & Southall, Citation2008).

Even had they preferred ‘tokens’ they wouldn’t have had the choice – early black elites inducted into corporate leadership were generally successful self-made business people or anti-Apartheid leaders. They had considerable leverage as a result of the white business’ desperate need to restock political capital. Moreover, the notion that they were simply pliant is false – they quickly took up cudgels against their white counterparts over the ‘informal’ nature of BEE. It’s true that the codified system with which they replaced it remained elite oriented, but to put this down to white interference ignores the fact that new black elites might have their own quite rational motives for preferring a circumscribed system of redistribution. Painting them simply as ‘junior partners’, with no evidence, strips them of agency.

Capital’s need for go-between’s with the ANC party-state wasn’t confined to the transition period. Reddy (Citation2023) shows that politically connected directors – almost all black – proliferated from the 1990s onwards and came to occupy central positions in the network of interlocking directorates. They appear to have formed the backbone of an ‘inner circle’ – a contingent of well-networked elites that assume a role of political leadership and articulate the class-wide interests of business. As Useem (Citation1984) showed long ago, inner circles tend to form out of outsider (non-executive) directors, and South Africa has been no exception to this. Some kind of functional differentiation of roles therefore seems to persist, in which white elites are overrepresented in top managerial functions and political control rests in black hands, although the discrepancies are slowly eroding with the growth of highly-credentialed black leaders with a background in business rather than politics. The spread of politically connected directors had a cohering effect on the interlock network, reinforcing density in the face of liberalisation. That network is highly integrated racially – which is likely to strengthen personal ties and common worldviews among the corporate elite.

4. Are black and white elites politically divided?

So far we’ve focused on knocking down the first of the three premises which WMC proponents would have to prove in order to justify the category – namely that whites control large corporations. But this doesn’t entirely recuse the issue because it is possible that white capitalists conspire together as individuals, even if they can’t do so as firms. Capital has ‘two faces’ as Burris (Citation2001) puts it. It’s true that the corporate face might be the more consequential. Structural power resides primarily in the corporate realm as it is here that the high-level decisions over investment, employment, and wages are made. The literature on ‘social’ and ‘hegemonic’ blocs treats firms, not individuals as constituent elements – for good reason.

And yet, individual capitalists and their collectives can still wield significant influence. Their financial clout might be diminutive in relation to corporate resources, but it’s often sizable enough to meaningfully impact political processes. Inequality aggrandises elite capacities – and South Africa is one of the most unequal nations on earth partly because of the outsized rewards claimed by CEOs and big investors. Individual expenditures are not constrained in the way corporate ones are, which might amplify their relative influence in certain domains. In the US for example, individual elites account for an overwhelming share of campaign donations (corporations tend to focus on lobbying) (Burris, Citation2001; Bonica, Citation2016). Corporate leaders have other sources of influence – notably personal connections to elites in other spheres like the media and politics, and other business actors. Through these connections, they might influence economic decisions – channelling structural power if not wielding it directly. Du Toit (Citation2019), for example, documents the role that Anton Rupert frequently plays as an intermediary and advisor for foreign investors interested in the South African economy.

Acting in concert, individual elites can magnify their impact and form shadow decision-making structures. This is what is alleged by the notion of a ‘Stellenbosch mafia’, which takes its name from the Western Cape town that has been the historic headquarters of Afrikaner elite society. But once again, despite the term’s popular resonance, no direct evidence of such a formation has yet been presented. Journalist Peiter Du Toit (Citation2019) wrote a book on the subject. He found resilient Old Boy networks with a vast reach of resources and influence – albeit ones beset by personal animosities and cultures clashes between ‘old’ and ‘new’ money. But he did not uncover any plots to usurp power from formal institutions. Rather he was sympathetic to the Afrikaner elite’s own sense of having been marginalised from the centres of governance. One could quibble with both his methods and his motives. The book is narrative rather than investigative in approach, and relies heavily on the testimony of the alleged mafioso themselves. Du Toit has an obvious sympathy for his subjects having himself lived and studied in Stellenbosch. But this is all we have to go on really. The social worlds of the white power elite remain unprobed by scholarly analysis.

This makes it more important to directly examine the third premise of WMC accounts, which holds that white elites are likely to behave politico-economically in distinctive ways to black elites. If white elites don’t have strong motives for pursuing a racial agenda then it matters less whether they have the capacity to or not. We’ve implicitly gone some way towards contesting that premise by showing that corporate leadership is integrated, because this also shows that black and white corporate elites have very similar material interests. Broadly, the fortunes of both – whether they be owners or directors – are tied into the same corporate assets. That will be a very strong impetus for unity. But it isn’t the end of the matter.

Interests across the two ‘faces’ of capital are not coextensive. Individual capitalists’ material interests are heavily shaped by the interests of the firms to which they are affiliated – but not reducible to them. In most cases, these individuals have an economic life that extends well beyond any single company. They possess a wide portfolio of investments and professional affiliations across a multiplicity of companies and entirely different asset classes like real estate. Nor can their material interests be mechanically deduced from their portfolios. The career trajectories and profit opportunities available to them are affected by a host of other factors, notably the networks in which they are embedded and the social and political capital they have access to. Interests might be affected by how elites are positioned in relation to existing systems of law and regulation, as a result of ascriptive identities or other factors. Black and white elites, for example, clearly have different interests in relation to BEE policies even if they aren't necessarily in conflict. In all of these ways and no doubt others, race is itself a determinant of material interests at a concrete level.

More to the point, it's obviously not the case that economic factors are solely determinative of elite political action. To assume otherwise, as some in the WMC debate seem to (Rudin, Citation2018), is to embrace a particularly extreme form of class reductionism. This is untenable. One can make plausible arguments for specific kinds of asymmetry in the causal weight of economic factors over elite political behaviour – I do exactly that below. But elites are not automatons processing ‘interests’ into political action. Like all of us, they are meaning-driven actors engaging the world through an ideological matrix conditioned by the social roles they inhabit and by idiosyncratic facts of their personal histories. Culture and ideology have some role in the way they make political decisions. They might filter and condition the ways that economic interests get interpreted into political preferences. But equally they might directly shape preferences across a whole set of issues over which economic interests have no direct bearing.

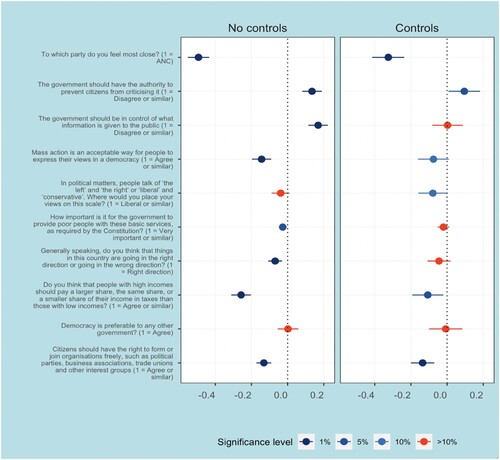

The extent to which race patterns the political opinions of the elite class is fundamentally an empirical question. Currently, it's largely unanswered. But it seems a given that should the research ever be done, its impact will be shown to be sizeable, however measured. South African society is deeply cleaved by race. We observe this in systematic disparities on moral, social and political questions in popular surveys (). These disparities narrow when controlling for income and other basic characteristics but don’t collapse entirely. It’s not possible to say exactly what they will look like within the elite sphere, but it is reasonable to expect that they will remain in some form. We have one small data point to suggest as much already: López et al. (Citation2022) find non-white elites (economic and otherwise) to be slightly more favourable towards redistributive policies, controlling for a range of factors (although statistical significance is weak). Were we to replicate the kinds of quantitative studies on elite preferences which have been common in the US and other more data-rich countries, coefficients on race would almost certainly be large and significant across certain possible outcomes. For example, it is almost certain that the heavily racialised patterns of party affiliation which we observe in the electorate as a whole will be mirrored at least to some extent within the economic elite (see first row of ). Accurately mapping the terrain of elite opinion is a major task for current research.

Figure 2. Race and political preferences.

Notes: Point estimate and 95% confidence interval of a binary race variable (1 = ‘white’) regressed on various political and moral opinions. Logistic regressions. Left panel are bivariate regressions, right panel includes controls for household income, gender and a geotype. Data is from the South African Social Attitudes Surveys 2017 (full sample N = 3173).

Yet however racialised political opinions might turn out to be within the South African elite, it remains extremely unlikely that deeply antagonistic blocs will form along racial contours. The basic reason for this is the asymmetric role that material interests – which are relatively homogeneous across racial groups – play in preference formation. In the foregoing we made the case that such interests don’t overdetermine political preferences, implying that space remains for (racialised) ideologies to impress upon political behaviour. But to accept this basic point is not to accept any equivalence between the role of ideology and interest. Class reductionism might be indefensible, class primacy is a different matter.

Note firstly that it isn't generalised class primacy that's at stake. The point to be proved is not that class (or really, material) factors ‘matter more’ than others for capitalists. Absent a well-specified set of outcomes in relation to which contending factors can be said to ‘matter’, statements of that kind rarely make any sense. We can begin to make a coherent case for class primacy here only because our outcome of interest is (relatively) clear: coalitional formation. Do material interests tend to be the common element around which ‘blocs’ – durable, high-level coalitions – coalesce? The centrality of material interests in the literature on ‘social blocs’, ‘hegemonic blocs’, etc. – both mainstream and Marxist – suggests that there is some general consensus that they do.

This doesn’t imply that we were wrong earlier to say that race can play a strong role in shaping political preferences. What it does imply, however, is that distinctions must be drawn between preferences of different kinds and prominence. For class primacy to hold, we need to believe that there is at least a substantial subset of preferences over which economic factors exert a dominant influence. Then, crucially, we need to believe that those preferences tend to be given greater weighting in the decisions affecting interest group formation, which could be seen as a function of the general salience accorded to economic issues. Economic concerns float to the top in the preference ordering of capitalists, in other words.

Why would that be the case? The simplest explanation revolves around the selective pressures to which capitalists are subject. Capitalism is a competitive social order. To reproduce themselves effectively in their own class location capitalists have to play by, and win through, the rules of the market. They have to generate some minimum threshold of profit by capturing and holding market share against the designs of other capitalists. But the economic struggle doesn’t contain itself to the factory floor. Both horizontal and vertical lines of division spill inevitably into the political arena. Capitalists combine to ensure that state policies undergird labour control. But they divide into ‘fractions’, ‘blocs’, and interest groups to agitate for policies which serve the particularistic interests of their own firms and sectors. The outcomes of those struggles can have enormous, oftentimes existential impacts on the competitive struggle. Firms and individuals which prioritise ideology over economic interest in orienting their politics will get slowly weeded out of the market.

This is a species of the argument that Chibber (Citation2022) makes in favour of an asymmetric casual power possessed by class structures. His aim is to show that, unlike other social structures, class doesn’t rely for its functioning on the internalisation of pre-given cultural codes that guide agents into the roles ordained by the structure. Culture, he argues, is ‘present’ in the class structure as it is in all social domains. Meaning-driven social action is the medium through which economic activity is practiced. But class is different in the ability that it has to endogenously give rise to meaning-orientations that align agents with its structural logic. Regardless of their antecedent dispositions, social actors are compelled to adopt ideational frameworks at the very least compatible with rules of reproduction defined by their social location. Culture ‘adjusts’ to class (29). Two things confer this power on class. Firstly, its sanctioning force: the fact that the penalties for contravening the rules of the class structure are extremely grave. Secondly, the low informational quotient associated with class roles. It's not hard for agents to understand the economic strategies that their class location impels them towards. No sophisticated process of acculturation is needed to convince workers of the necessity of looking for a job, for example.

The mechanisms of the class structure, however, look different depending on the level of abstraction at which we are theorising it. Class has the omnipotence it seems to in Chibber’s handling of it, because he is working at the highest possible abstraction. His purpose is to account for the universality of the most basic modes of economic action associated with capitalist property relations – the propensity for workers to sell labour power and for capitalists to profiteer. The object of our theorising cannot be dealt with meaningfully on the same plane. The coalitional strategies of capitalists, like their political habits generally, are inherently conjunctural and historical. However, with the move downwards towards the concrete-political, the case for class primacy becomes harder to make. The sanctioning force of class imperatives declines with such a move and the informational quotient of class roles increases. The penalties for failing to obey the profit imperative are existential for a capitalist. The penalties for failing to optimise solely over economic interest in political action may not always be. Moreover, the task of understanding how economic interests are best served in specific historical conjunctures is far more complicated than is the task of decoding the basic strategies of survival on the market. In the translation of basic interests into strategic preferences, scope certainly exists for ideology to interfere.

And yet, the same basic processes of selection are at work even if they operate with slightly less force. Capitalists that systematically favour idiosyncratic beliefs and ideologies over economic self-interest in their political practice should expect to bear heavy costs. Those costs will winnow the ideologically intransigent out of the market. And this process of winnowing itself will redound on the survivors, impressing upon them the imperative for economically rational politics. Businesspeople who’ve already made it to the summit of corporate power tend to have already internalised this imperative. At a conjunctural level the political behaviour of capitalists might be messy, subject to a plethora of determinations, but material interest still generally governs above all. The caveat there is important – until we’ve done the empirical work we can’t fully put to bed the possibility of deep ideological fragmentation – our point here is to demonstrate theoretical grounds for scepticism.

Yet what has far argued is still insufficient for that objective. Given the more concrete plane of analysis in which we are working, what we’ve above called class primacy is mislabeled. What we’ve actually made a case for is the primacy of material interests over (certain kinds of) political action. Previously, however, we explicitly made room for the fact that material interests in a concrete setting are not a simple function of class position – they are influenced by race and many other factors. Hence race has a backdoor into the determination of political outcomes even when purely ideological channels of influence are blocked. How then can we be sure that economic rationality doesn’t steer the capitalist elite into blocs delimited by racial boundaries? Not through any abstract procedure. The extent to which race influences material interest is historically, not theoretically determined.

In fact, it is a simple scan of the concrete terrain of race politics in contemporary South Africa that makes most clear the improbability of a White Monopoly bloc. The current racial order in the country simply does not shape an issue agenda likely to foment sharp intra-corporate polarisation along racial lines. We can of course identify issues likely to create some division, but none of these have any likelihood of becoming dominant fault lines. The party system in the country is heavily racialised which, given the electoral dominance of a ‘black’ party, means a highly skewed distribution of political capital, which might in turn shape accumulation strategies. Seekings & Nattrass (Citation2011: 353) argue that this leads to some disjuncture of interests because the opportunity for get-rich-quick BEE schemes disincentivises black elites from ‘engaging in substantive entrepreneurship’ and instead encourages ‘tapping speculatively into the profitability of established business’. Black business people may thus have some indirect interest in the profitability of corporations, but their primary concern is in sustaining their own basis for accumulation – their political capital. There is probably something to the point even if they overstate it, and even if it's being slowly invalidated by the gradual rise of a black professional class. Either way, rather than conflict, the most this seems to have led to is a partial division of labour, in which white and black elites differentially allocate into managerial and political functions, but without this obstructing common class interests in any visible way.

Beyond this, the only issue with any potential to spark deep antagonism is BEE, which is the only formalised element of discrimination in the current dispensation. And yet it hasn’t, at least in the current period. There were conflicts in the past – black corporate elites like Cyril Ramaphosa led the charge to replace the voluntarist ‘first-stage’ of BEE with the current statutory system. These seem to have quickly resolved themselves into the present consensus which has largely held for two decades, stabilised by the gains white elites yield in terms of legitimation and elite cohesion. That consensus only encompasses the top – corporate – strata of the capitalist class, to be sure. Certain smaller, non-corporate business chambers and black professional associations remain viscerally opposed to the existing system. But they don’t seem to have found much sympathy for their cause among the black corporate bourgeoisie, who might be accused of ‘kicking away the ladder’ – resisting the extension of policies they themselves used to secure their initial ascent. Firm type, or in other words class, remains the main faultline of inter-capitalist conflict – not race.

This could all change. Nationalist formations like the Radical Economic Transformation faction of the ANC and the Economics Freedom Fighters espouse a far more muscular program of redistribution, aiming to squeeze whites out of the economy. Were such a grouping to secure a firm grasp on power it’s conceivable that this might rupture the corporate elite. Some segments of the black corporate bourgeoisie might find their interests better served by aligning with the new regime and seeking a share of the rents. But they would inevitably find themselves drawing from a rapidly dwindling pile as any appropriationist turn in South Africa’s open economy will completely devastate corporate wealth. Black corporate leaders are highly unlikely to see any gain in their net position. This is well understood, which is why – anecdotally at least – they seem to be equally opposed to radical strains of black nationalism as their white counterparts. Of course, there are also less extreme scenarios which might provoke ruptures. The move away from one party dominance towards a competitive party system will create strain if racial divisions are also partisan divisions as seems likely. It’s difficult to predict how this will play out with better research on the precise dynamics of cohesion and contestation in the elite.

5. Pathways for research beyond WMC

Notions of WMC, we’ve argued, overstate the salience of race in (corporate) elite politics. But we’ve also rejected the argument, implicit in certain critiques of the concept, that race has no significance at all for the elite. In this section, we outline avenues for researching that significance, focussed on the subjects of cohesion, preferences and power.

In making the case that there is no fundamental antagonism between black and white corporate elites we’ve already said something about cohesion – but not much. Cohesion is a vast spectrum. We presently have little clue as to where the South African ruling class falls on it. Reddy’s (Citation2023) paper is one of the few in recent years to take an interest in cohesion, adopting a structuralist lens in the sense of studying the ‘concrete interpersonal and organizational relations in which actors are embedded’ (Mizruchi & Schwartz, Citation1987: 8). He finds that processes of black elite formation partly counteracted fragmentary pressures arising from liberalisation, allowing the South African corporate network to retain some density. But on its own, it reveals only a thin slice of the structural picture. There is plenty of scope, firstly, for extending this work to encompass the many other institutions and organisations that configure inter-elite relations. Broadening out from directoral interlocks to also account for common ownership ties in the corporate network would be a straightforward next step. Business associations and think tanks have been shown to be important for fostering cross-elite networks – they ought to be integrated into this analysis (Murray, Citation2017).

Perhaps more importantly, structuralist approaches ought to look beyond the formal economy and start investigating the private lifeworlds of the elite. It’s one of the most durable and emblematic findings of the broader field that elite social spaces tend to be densely integrated (Domhoff, Citation2017). Elites mix and merge continuously through an array of cultural, educational, and social institutions – exclusive schools, golf clubs, retreats etc. But do we find the same thing in South Africa? The question is compelling because of the historical context. Democratisation shook the elite power structure at its foundations. We know that white elites responded in part by seeking out new allies among political-connected black business people. But the details of post-Apartheid elite formation remain very murky. Were the alliances formed ones of thin expediency or something deeper? If the socio-spatial separation between black and white elites has eroded steadily we might conclude the latter. But it seems more likely that we will find an elite that remains to some degree socially divided even as it’s become institutionally and politically united. This would be a somewhat unique configuration. It might offer a valuable opportunity for testing the importance of dense social ties, independent of other ‘cohering’ institutions.

Structural cohesion is not substantive cohesion however. It's a common fallacy to conflate the two but their actual relation is better understood as one of cause and effect. The primary reason we’re interested in institutional and social ties is that they tend to foster common views and coordinated action. But they don’t do so determinatively – myriad factors might confound and deflect the centripetal forces of social networks. Ultimately cohesion needs to be studied directly. Preference mapping is one obvious way in which to begin this project. The field is wide open for surveys of elite opinion, which can start to give us a picture of how closely the worldviews of different elite segments are actually aligned. Race will naturally be a significant marker in any attempt to sketch out the contours of agreement and division. But the trick for this research will be to avoid lazy explanations which reduce the whole spectrum of racial variation to direct cultural effects. Naturally, the actual causal nexus between race and political outlook is even more complicated than the foregoing discussion suggests. Race is correlated with an array of biographical and social positional characteristics of elites – their relationships to political and state actors, their class trajectories, their educational affiliations, their geographic linkages, etc. All of these are likely to have had some effect on elite opinions. Such factors will only be illuminated by survey designs that carefully allow for intra-racial variation.

Surveys are useful but, on their own, also partial. Elites might misunderstand, or misreport their own political situation. The nuances of political disputation are often hard to capture with one dimensional question sets. Other methods will have to fill in the gaps. Perhaps the most pressing need is for historically-oriented research, drawing on interviews and archives to offer us a clearer picture of corporate politics in action. Indeed, the last monograph length attempts to provide detailed descriptions of how business actors have organised, the issues that have motivated them and the success and challenges they’ve faced are now more than a decade and a half old (Taylor, Citation2007; Handley, Citation2008). They entirely precede the Zuma era with all the ructions it brought. Race was never their major focus – so they provide little insight into the texture of the relationships forged between old and new elites, or the different roles and functions each have assumed in emergent power structures.

6. Conclusion

The general lack of scholarly research has left us with hazy, conflicting narratives of corporate politics at a macro level. On the Left, many see large-scale capital or the ‘Minerals-Energy-Finance Complex’, as having maintained an enduring political hegemony, undisturbed by the gyrations of power inside the ANC (Ashman et al., Citation2013). In contrast, corporate leaders themselves depict relations with the democratic state and its managers as far more fractious, even during the Mbeki era (Spicer, Citation2016). Under Zuma, fissures widened dramatically. There is clearly something to this account – Zuma ended his administration in a state of all out war with ‘white monopoly capital’. It was by then clear that his own coalition has come to centre on a rivalrous, ‘tenderpreneurial’ fraction of business rooted in the circuits of a giant ‘informal economy’ of rent-seeking which metastasised under administration (Von Holdt, Citation2019).

And yet big business was hardly impotent during this period. Some reports suggest that it was large-scale bankers, threatening capital strike, who played the pivotal role in rebuffing Zuma’s initial attempt to establish personalised control over the National Treasury in 2015 – which would’ve been a capstone move in his ‘state capture’ project (Du Toit & Basson, Citation2018). Zuma did succeed in installing a Gupta-linked loyalist – Malusi Gigaba – as Treasury minister two years later in 2017. But Gigaba was quickly forced to adapt to dominant institutional logics during his short tenure. The market orthodoxies favoured by big business remained largely in place.

Moving beyond a one dimensional conception of power, it might be better to understand the changes we’ve witnessed as a reconfiguration of elite resources of power. Both personalised and formal channels of coordination with the political executive were disrupted following Mbeki’s removal. Rents from the ‘informal economy’ reduced the Zuma faction’s dependence on corporate largesse. Yet large corporations maintained their ‘structural prominence’ in the economy, dominating investment and employment flows (Young, Citation2015). Thus in a general sense, big business appears to have experienced a depletion of instrumental power under Zuma while structural power was broadly preserved. Corresponding to this transformation in the form of corporate power was, it seems, a change in the content of that power, or put differently a shift the ends to which power was used. Business seems to have had less scope for ‘selective determination’ under Zuma – the ability to dictate which policies make it on to the agenda (Kalaitzake, Citation2022). However, it has maintained capacities for ‘limit determination’ – the ability to set boundaries in which the government operates. Specifically, corporate power seems to have registered itself primarily through the erection of high guardrails around key neoliberal institutions and policies, even as big business increasingly lost say over the day-to-day affairs of the government.

If there is any accuracy to these conjectures, they suggest that the story of post-Apartheid corporate politics is probably more complicated than dominant hazy narratives suggest. More rigorous empirical work stands to shed new light on that story. But if it's to do so, our analysis clearly can’t stay confined to the upper rungs of the business system. It will have to encompass other segments of smaller, private business, particularly state-linked black businesses which have become so influential in recent years. The growing antagonism between these two competing factions of the elite seems to have been a decisive feature of post-Apartheid politics. Yet here the absence of scholarly research is even more glaring. Black business associations were subjected to close sociological scrutiny in the late-Apartheid period but have been largely ignored since. There is a common tendency to compress such associations with other segments of non-corporate black business into a single monolithic category of ‘tenderpreneurial’ capital. But how adequate is this? What kind of cohesion and coherence exists among this fraction of the elite? And does indeed constitute a clearly distinguished ‘fraction’ or are the lines between in and the ‘corporate bourgeoisie’ in reality far more blurred, as some analysis would suggest (Cronin & Mashilo, Citation2017; Nxele, Citation2022)?

There is, in short, a wealth of work to be done on the political economy of business which takes race as a central category of analysis. The paucity of essentialist tropes stirred up the notion of ‘white monopoly capital’ should not obscure that.

Acknowledgements

The author is very grateful to Aroop Chatterjee, Arabo Ewinyu, and Ujithra Ponniah and two anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback. All errors remain his own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Aboobaker (Citation2019) is one of few other scholarly interventions into the debate, but his focus is on the ‘monopoly’ part of WMC. He doubts the intellectual traditions associated with the ‘monopoly capitalism’ school of analysis have much to offer us today. My focus here is on the racial question, as should already be clear.

2 The biggest trend in ownership in recent years has been the meteoric rise of passive index funds, sparking a major debate over the governance under ‘asset manager capitalism’ (Braun, Citation2021).

References

- Aboobaker, A, 2019. Visions of stagnation and maldistribution: monopoly capital, ‘white monopoly capital’ and new challenges to the South African left. Review of African Political Economy 46(161), 515–23.

- Ashman, S, Fine, B & Newman, SA, 2011. The Crisis in South Africa - Neoliberalism, Financialization and Uneven and Combined Development. Socialist Register, 47 (The Crisis This Time).

- Ashman, S, Fine, B & Newman, SA, 2013. Systems of accumulation and the evolving MEC. In Fine, B, Saraswati, J & Tavasci, D (Eds.), Beyond the developmental state: industrial policy into the 21st century (pp. 245–68). Pluto Press, London.

- Beresford, A, Beardsworth, N, Findlay, K & Alger, S, 2023. Conceptualising the emancipatory potential of populism: A typology and analysis. Political Geography 102, 102808.

- Bonica, A, 2016. Avenues of influence: on the political expenditures of corporations and their directors and executives. Business and Politics 18(4), 367–94.

- Braun, B, 2021. Asset manager capitalism as a corporate governance regime. In Hacker, JS, Hertel-Fernandez, A, Pierson, P, & Thelen, K (Eds.), The American political economy: politics, markets, and power (Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics) (pp. 270–95). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Burris, V, 2001. The two faces of capital: Corporations and individual capitalists as political actors. American Sociological Review 66(93), 361–81.

- Chibber, V, 2022. The class matrix: Social theory after the cultural turn. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Cronin, J & Mashilo, AM, 2017. Chris Malikane and the Gupterisation of Marxism.

- Desai, A, 2018. The zuma moment: between tender-based capitalists and radical economic transformation. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 36(4), 499–513.

- Domhoff, GW, 2017. Studying the power elite: Fifty years of Who rules America? Routledge, New York.

- Du Toit, P, 2019. The Stellenbosch mafia: Inside the billionaire’s club. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg.

- Du Toit, P & Basson, A, 2018. 9/12: How Zuma was forced to re-appoint Gordhan as finance minister. News24, 20 Nov.

- Fine, B & Rustomjee, Z, 1996. The political economy of South Africa: From minerals-energy complex to industrialization. Westview Press, Boulder.

- Ford, G, 2018. NYT joins campaign to purge the term, “white monopoly capital” in South Africa. MR Online.

- Gqubule, D, 2021. Black economic empowerment transactions in South Africa after 1994.

- Habiyaremye, A, 2022. Racial capitalism, ruling elite business entanglement and the impasse of black economic empowerment policy in South Africa. African Journal of Business Ethics 16(1), 25–41.

- Handley, PA, 2008. Business and the state in Africa: Economic policy-making in the neo-liberal era. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- HSRC, 2017. South African social attitude surveys.

- Kalaitzake, M, 2022. Structural power without the structure: A class-centered challenge to new structural power formulations. Politics & Society 50(4), 655–87.

- Khan, F & Mohamed, S, 2023. Elites and economic policy in South Africa’s transition and beyond. International Review of Applied Economics 37(6), 1–23.

- Lehulere, O, 2017. Cronin & Company Harness Marxism to the Service of White Monopoly Capital.

- Lepuru, M, 2023. The delusion of apartheid and the African National Congress: Sizwe’s mythmaking and South African politics. The Strategic Review for Southern Africa 45(1), 94–103.

- López, M, Moraes Silva, G, Teeger, C & Marques, P, 2022. Economic and cultural determinants of elite attitudes toward redistribution. Socio-Economic Review 20(2), 489–514.

- Majavu, M, 2023. Laundering racial capitalism in post-apartheid South Africa. Politikon 50(3), 1–15.

- Makhaya, G & Roberts, S, 2013. Expectations and outcomes: Considering competition and corporate power in South Africa under democracy. Review of African Political Economy 40(138), 556–71.

- Malikane, C, 2017. Concerning the current situation. Khanya Journal 36, 1–8.

- Mizruchi, MS & Schwartz, M, eds. 1987. In Intercorporate relations: The structural analysis of business. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Mpofu-Walsh, S, 2021. The new apartheid. 1st edn. Tafelberg, Johannesburg.

- Murray, J, 2017. Interlock globally, Act domestically: Corporate political unity in the 21st century. American Journal of Sociology 122(6), 1617–63.

- Nxele, M, 2022. Crony capitalist deals and investment in South Africa’s platinum belt: A case study of Anglo American platinum’s scramble for mining rights, 1995–2019. Review of African Political Economy 49(173), 395–416.

- O’Meara, D, 1983. Volkskapitalisme: Class, capital, and ideology in the development of Afrikaner nationalism, 1934-1948. Ravan Press, Johannesburg.

- Padayachee, V, 2013. Corporate governance in South Africa: From ‘old boys club’ to ‘ubuntu’? Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 81(1), 260–90.

- Patel, K, 2017. Deconstructing ‘white monopoly capital’. The M&G Online.

- Reddy, N, 2023. Liberalization, democratization and the remaking of the South African corporate network 1993–2020. Socio-Economic Review 21(1), 213–42.

- Rudin, J, 2018. What’s in a name? White Monopoly Capital. Daily Maverick.

- Seekings, J & Nattrass, N, 2011. State-business relations and pro-poor growth in South Africa. Journal of International Development 23(3), 338–57.

- Southall, R, 2014. The African middle class in South Africa 1910–1994. Economic History of Developing Regions 32(3), 1–24.

- Southall, R, 2017. White monopoly capital: good politics, bad sociology, worse economics. The Conversation.

- Spicer, M, 2016. The business government relationship: what has gone wrong? Focus 78(3), 1–16.

- Steyn, L, 2011. Busa exposed to transformation by fire [online]. The M&G Online. Available from: https://mg.co.za/article/2011-09-16-busa-exposed-to-transformation-by-fire/ Accessed 15 August 2017.

- Tangri, R & Southall, R, 2008. The politics of black economic empowerment in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 34(3), 699–716.

- Taylor, SD, 2007. Business and the state in Southern Africa: The politics of economic reform. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder.

- Thomas, L, 2017. Ownership of JSE-listed companies. National Treasury.

- Useem, M, 1984. The inner circle. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Von Holdt, K, 2019. The political economy of corruption: elite-formation, factions and violence. SWOP Working Papers 10, 32.

- Young, K, 2015. Not by structure alone: power, prominence, and agency in American finance. Business and Politics 17(3), 443–72.

Appendices

Appendix 1. BEE management and control.

Code Series 200 – Management control.