?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

People who live in poverty struggle to focus on the future as they are forced to deal with their current challenges, which can impact the learner during learnership programmes. The study investigated the effect of poverty challenges on youth learnership success. This was a cross-sectional quantitative descriptive study where 156 responses were obtained from the youth in learnership programmes across the SETAs from 2019–21. Study results show that poverty challenges have a negative effect on the rate of learnership success. This relationship is moderated by personal development and enhanced employability. The results are influenced by socio-demographic and programme structure control variables. At current poverty levels, skills development is at the forefront of improving employment prospects in South Africa and alleviating a critical constraint to economic growth.

1. Introduction

Unemployment is the primary source of poverty and inequality, especially in developing countries such as South Africa (Le Pere, Citation2020). This is especially true for the South African youth as aged between 14 and 35 (The Presidency, Republic of South Africa, Citation2015; Statistics South Africa, Citation2023). The confluence of poverty, unemployment, and inequality poses a significant challenge to South Africa's aspirations of achieving a developmental state (Tshishonga & Matsiliza, Citation2021). Statistics South Africa (Citation2023) shows that South Africa’s unemployment rate was at 32.9% in the first quarter of 2023, with the rate in youths aged 15–24 years being 62.1% and in those aged 25–34 years being 40.7%. This means that more 4.9 million youths under the age of 35 years were unemployed in this period. Significant contributors to unemployment are lack of skills and lack of formal work experience amongst South African youth (Kingdon & Knight, Citation2004; Graham et al., Citation2019; Statistics South Africa, Citation2021). This is a key obstacle to economic growth as businesses are unwilling to employ unskilled young people at the current wage rate as it is difficult and costly to determine whether they will contribute positively to the business (Visser & Kruss, Citation2009). Thus, many South Africans remain disadvantaged due to not having the required skills and level of education (Erasmus et al., Citation2019).

To mitigate these challenges, the government introduced skills’ development interventions termed learnership programmes as part of the National Skills Development Strategy (NSDS) to alleviate the shortage of skills in the country and, in turn, reduce unemployment (Erasmus et al., Citation2009). Learnerships, supported by the Sector Education and Training Authority (SETA), is one of the government flagship programmes that provide learners with skills and increased employment opportunities within the market (Akbar et al., Citation2016). This aligns with human capital theory, which describes the importance of government investing in its people as it leads to improved quality of skills (Piketty, Citation2014).

The theory of human capital posits that the acquisition of skills and training through investment in education is a prerequisite for enhancing individual capital. As such, human capital theory is a dominant discourse on the knowledge economy around the globe, with the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) using it in tandem with the knowledge economy to shape its practical applications within society (Takayama, Citation2013). In South Africa, learnership initiatives aim to address the problem of skills shortage and maximise the employability of its citizens. The learnership programme integrates work experience and provides an opportunity to promote skills development through workplace learning and relevant theoretical learning paths to build a skilled workforce (Visser & Kruss, Citation2009; O’Neil et al., Citation2023). This addresses the primary aim of training low-skilled young people and providing them with the skills required to facilitate their entry into jobs. Despite the importance of learnership, South Africa and other developing countries have reported on low impact of learnership programme on employment (De Louw, Citation2009; Grewe et al., Citation2012; Rankin et al., Citation2014; O’Neil et al., Citation2023). This is due to several factors such as lack of support from senior management and commitment from mentors, lack of capacity to host the learners, and recruitment processes that are not transparent. This situation is exacerbated by socio-economic factors and there is a dearth of studies on how these factors are making things worse. This given that a large percentage of learnership beneficiaries are youth from disadvantaged backgrounds who are daily impacted by the ‘triple challenge’ of unemployment, poverty and inequality (Koyana & Mason, Citation2017; Botha et al., Citation2023). These studies do not provide a view of how these challenges impact learners or why a large percentage of learners continue to drop out of training opportunities that might potentially grant them employment. Thus, providing a need for this study to understand how poverty, an embedded fundamental problem in South Africa (Francis & Webster, Citation2019; Gumede, Citation2021), affects the success rate of the learnership programme. The research question for this study is:

What are the effects of poverty challenges on the learner success rate attending SETA-led learnership programmes in South Africa?

1.1. Overview of poverty as part of the ‘triple challenge’

Inequality, poverty and unemployment are interdependent socio-economic challenges labelled as the ‘triple challenge’ in South Africa (Perry, Citation2019). All stakeholders agree that this requires urgent attention from policymakers and leaders across South African society. Poverty is regarded as a silent killer and is considered one of the world’s most stubborn challenges (World Bank, Citation2013) and the consequences of poverty and unemployment profoundly affect human dignity (Akanbi, Citation2016). In South Africa in 2022, the level of poverty was estimated at 62.6% as based on the upper-middle-income country poverty line (World Bank, Citation2023). The COVID-19Footnote1 pandemic and other financial constraints exacerbated this situation as most economies were brought to a standstill for an extended period (World Bank, Citation2020). Thus, South African consumers are experiencing significant financial pressure. According to the Deloitte South Africa Consumer Tracker report released in February 2023, a significant proportion of consumers (41%) have reported a decline in their financial status over the past year and are apprehensive about their financial situation. The national poverty line links well-being to the consumption of goods and services relating to food and non-food components of household consumption expenditure (Statistics South Africa, Citation2022). As a result, consumers are making significant adjustments in response to the escalating cost of food to prioritise cost-effectiveness, such as opting for lower-priced food and to demonstrate greater frugality by minimising food waste, purchasing only essential items, and reducing overall consumption (Deloitte, Citation2023). This phenomenon is made worse by the prevailing high levels of unemployment, which in turn contributes to poverty (Gebel & Gundert, Citation2023). Zizzamia (Citation2020) named unemployment as the major contributing factor to poverty in South Africa. This is even more of a challenge in South Africa which has one of the most unequal societies globally in terms of income distribution (Pabón et al., Citation2021). Some of the economic and social implications of unemployment in a country may result in the erosion of human capital, social exclusion, protests, increased crime rates and unhealthy societies (Kingdon & Knight, Citation2007; Cloete, Citation2015; Makaringe & Khobai, Citation2018). Even though the government has tried to implement various policies and strategies to mitigate high unemployment amongst the youth, the results have not been fully realised (Ferreira & Rossouw, Citation2016; Jubane, Citation2020).

1.2. Poverty and skills development

Skills development programmes are important to overcome poverty and to ensure that individuals are allowed to enhance their lives and become more employable (Rankin et al., Citation2014). Poverty is known to adversely effects individuals, ranging from psychological to physical well-being as individuals experiencing poverty are known to live for the moment with little to no consideration for the future because they focus on overcoming immediate challenges (Van Lancker & Parolin, Citation2020). This might impact on how motivated learners are while they attend skills and learning programmes. Other influences include lack of nutrition as a fundamental problem associated with poverty as it means that those from disadvantaged households struggle to regularly feed themselves (World Bank, Citation2013). This can lead to a lack of energy, concentration and demotivation and ultimately a feeling of hopelessness resulting in their discontinuing learning programmes. Most SETA educational facilities are in the urban areas and this has huge implications on commuting costs as most unemployed learners reside in townships or rural towns (Centre for Development & Enterprise, Citation2017). Some learners do not receive any stipend (Keep Climbing, Citation2017) but they nevertheless register with hopes of employment in the future. Other learners receive a stipend each month based on their selected qualification to cover basic needs such as food and transport and this minimum wage is governed by the Department of Employment and Labour (SETA, Citation2013).

Some of the complaints from registered learners for the SETA learnership programme include going months without being paid because the government does not pay employers on time. For those without a strong supporting structure, this can cause substantial financial strain – including going days without food and not being able to attend training (Keep Climbing, Citation2017). In addition to receiving a low stipend which may only cover transport and lunch, other challenges learners face include working long hours and the expectation to work overtime and weekends, the need to also contribute to their households, and a company deduction from their stipend when the learner is sick.

1.3. Skills development, economic development and competitiveness

Fourie & Burger (Citation2009) explain unemployment as the situation where the supply of labour exceeds demand or the price of labour is too high for organisations to afford additional labour. The inability of the economy to create jobs coupled with the high-level entry requirements and the skills mismatch are some of the reasons unemployment continues to rise (Neely, Citation2010).

Education and prior work experience play an important role in the labour market so that employers often prefer to employ those with previous work experience and a higher level of education. Unfortunately for the youth, lack of work experience is a stumbling block that results in their finding it hard to secure employment. Fourie & Burger (Citation2009) posit that skilled labour can be challenging to find in most skilled and professional segments primarily due to the poor state of the public education system. Education has a strong influence on labour market participation and in a developing economy such as found in South Africa, there is a possibility that significant employment vacancies can exist in parallel with high levels of unemployment (Neely, Citation2010). Overcoming these challenges is critical, given that unemployment has a massive impact on inequality and poverty (Francis & Webster, Citation2019; Mwakalila, Citation2023). The poor households tend to struggle more to get employment, especially the youth due to lack of resources and mobility for a job search or the ability to relocate as jobs could be located far from their homes. In some cases, underdeveloped transport and high commuting costs and the threat of crime make the job search more difficult and raise associated expenses (Anser et al., Citation2020; Zungu & Mtshengu, Citation2023). As a result, a shortage of skills was long identified as one of the critical constraints to economic growth and employment creation by the South African government. Rasool & Botha (Citation2011) indicate that the South African educational system also contributes to a shortage in skills as it is unable to produce skills required to develop the country’s economy. Learnership programmes were introduced to try and bridge this gap.

2. Conceptual model of the study

The learnership system came into effect in South Africa in 2001 and it is regarded as a critical segment of the National Skills Development Strategy (NSDS), and it teaches both theory and learning practical skills in a workplace (Akbar et al., Citation2016; O’Neil et al., Citation2023). There has been a notable increase in the number of learnerships provided by the SETAs in recent times (Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2018; Botha et al., Citation2023). Hays & Reinders (Citation2018) argue that upskilling citizens helps address socio-economic challenges amongst others poverty. Kingdon & Knight (Citation2007) indicate that skilled people increase productivity and reduce inequality and instability. If the government does not train people, this will result in companies sourcing required skills from other countries. The outcome of this will worsen the South African economy, leading to more people being unemployed and unable to provide for their families resulting in even more inequality and poverty. Within a country that is struggling with high levels of poverty, it is critical to understand the effect of poverty challenge in the rate of learnership success. What is evident is that there are other dynamics that influence the complexity of the poverty challenges on rate of learnership success. For example, Jyoti et al. (Citation2005) explain that individuals experiencing hunger are more likely to have problems with memory and concentration because they do not have the energy to carry out functions. Lack of concentration to absorb information can lead to demotivation, inability to learn and eventually dropping out of the programme due to the inability to complete the required task.

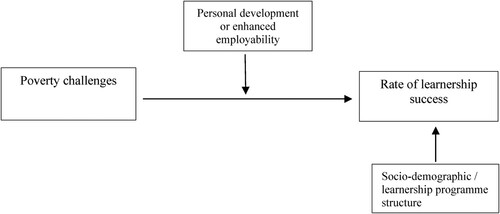

Marshall & Rossman (Citation2016) explain the moderator as variables that links the independent variable (poverty challenges) to the dependent variable (rate of learnership success), as a result connecting the two variables. In the study, the moderating effect was investigated with two learning outcomes, personal development of the learner as well as their enhanced employability. The learning outcome assist to shift the focus from instructors to the learners’ learning processes (Havnes & Prøitz, Citation2016; Erikson & Erikson, Citation2019). Harris & Clayton (Citation2019) posit the classification of these self-reported learning outcomes with some of these being key skills acquisition and development. This is the process-based learning outcome, while the end goal is the employability. Visser & Kruss (Citation2009) highlight the importance and linkage of skills development and employability of learners. In supporting this view, O’Neil et al. (Citation2023) explain that the learnerships have the potential to provide learners with the necessary skills to enter the economic market. Simply put, it advances employability of the learners. This creates opportunities for the learners to advance themselves and contribute productively to the society. The model of the study is presented in .

3. Materials and methods

The study employed the cross-sectional quantitative correlational research design (Mtotywa, Citation2019), which was used to determine the influence of the poverty challenges on the rate of learnership success. As such, the study was influenced by a post-positivist paradigm (Bryman et al., Citation2014).

3.1. Population and sample

The target population is made up of unemployed individuals aged between 18 and 35 years. This group falls into the official definition of ‘youth’ in South Africa. The individuals were registered for the learnership programme between 2018 and 2020 within the registered SETA-supported learning programmes. The sample size was based on the guidelines of multiple regressions by Green (Citation1991):

(1)

(1) where

is the number of predictors, which includes the seven control variables and the interaction variable in this study, producing a minimum sample size of 122. The adequacy of the sample size was confirmed with a post hoc power analysis in GPower 3.1. F-tests were employed, utilising linear regression: fixed model with R2 deviation from zero, with a final sample size of the study of 156 and a Cohen’s f2 = 0.282, the power (1 – β err prob) = 0.99, which indicates the adequacy of the sample size as it was higher than the acceptable power ≥ 0.80.

3.2. Instrument and data collection

The study questionnaire is an adaptation of the questionnaire developed for a similar study by Grewe et al. (Citation2012). The empirical data was collected over three months using an online platform. The standard ethical procedures and guidelines were followed in the study, with the ethical clearance obtained from Tshwane University of Technology [FCRE2020/FR/02/005-MS (2)].

3.3. Data analysis

The data analysis was computed in Stata 14, with the data cleaned, ensuring that the responses did not have more than 5% missing values and there were no extreme outliers. The central tendencies were analysed with mean and dispersion using standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis to confirm the normal distribution of the variables. The multiple regression model was used to determine the influence of poverty challenges on learner rate of success. The model for the study was investigated using a bivariate ordinal least square regression model, which states:

(2)

(2) where

is the learner success rate while

is the poverty challenges. The objective was to determine the effect of a predictor variable on learner success rate through understanding if

is statistically significant.

signifies the constant with

the error term. We included the control variable to eliminate omitted variable bias. Gender, age, education level and the number of dependents were controls for the socio-demographic factors. At the same time, sector of learnership, registered SETA and duration of the learnership were controls for programme structure variables. As such, the updated model is as follows:

(3)

(3) with

being gender,

is age,

is education,

is the number of dependents, while

is sector of learnership,

is the registered SETA and the duration of the learnership and

the duration of learnership. Critically though, the key assumption that need to hold is the conditional means independence, which is:

(4)

(4) This indicates that the expected value of the error term,

is conditional to all the regressor variables,

is equal to the error term,

conditional to all the regressor variables except

. This means that causal variable,

and the error term,

are uncorrelated when we control for the socio-demographic and learnership programme structure variables, with

.

The model specification was confirmed by validating the key assumptions of multicollinearity with the variance inflation factor (VIF), homoscedasticity with Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity, serial correlation with Durbin-Watson d-statistic and normality of the residual with Jarque-Bera normality test. In cases where these assumptions are violated, we estimated the variances of OLS estimators (and standard errors) by using White-Huber standard errors or heteroscedasticity robust standard errors using :

(5)

(5) To evaluate the moderating effect an interaction term was added in the regression (Hair et al., Citation2021). The moderating variables were personal development and enhanced employability.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and learnership information

A total of 156 respondents completed the questionnaire, and their demographics are indicated in . 53.2% of the responses were from females while the other 46.8% were from males, with 73.7% of responses from individuals aged between 26 and 35. Within these respondents, 30.8% had matric (grade 12) or less as their highest qualification, while 19.9% had NQF5 – N6 Certificate, and 18.6% had a National Diploma – NQF6. Further, 20.5% had a degree or advanced diploma (NQF7), and 10.3% had a postgraduate degree (NQF8-10) as their highest qualification. This indicates that unemployment in South Africa cuts across all qualifications.

Table 1. Profile of the respondents.

Of the respondents, 69.6% had dependents, while the other 31.4% had no dependents while 67.9% of respondents were from the public sector, and the remaining 32.1% were from the private sector. Most of the study participants were from Service SETA (42.3%), followed by other SETA programmes (23.1%) and MerSETA (12.2%). Most (55.1%) of the respondents were registered for a learnership programme that had a contract of 1 year, followed by 41.0% registered for a 2-year duration, and 3.9% of the respondents were enrolled for three years or more.

4.2. Learnership outcomes and rate of success

Under learnership outcomes and rate of success, the variables with the highest means were VAR12 (I have acquired new skills through the programme) with mean M = 3.94 (SD = 1.039), followed by VAR13 (learnership programme is beneficial to my career development) with mean M = 3.90 (SD = 1.052). These variables confirmed that there were good learning outcomes (personal development), with Cronbach Alpha for reliability α = 0.861. The respondents also acknowledged that their learnership was enhancing their employability, indicating in VAR14 that the programme adds value to their job function in the workplace (M = 3.88, SD = 0.977) ().

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of learning outcomes and rate of success.

Based on the guidelines of George & Mallery (Citation2003), the Cronbach Alpha for Personal development was α = 0.861 and enhanced employability α = 0.908 indicate that both these constructs (personal development and enhanced employability) were reliable. The skewness and kurtosis of the variables were within the acceptable normality range (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Based on the five-point rating scale, where 1 = unsuccessful and 5 = extremely successful, the majority of the respondents confirmed that the learnership was a success, with a mean M = 3.88 (SD = 0.882) and a median of 4.00, with 25% (Q3) indicating a score of 5.00. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to determine the possible statistical difference between the SETAs. The results show that there is no statistically significant difference in the mean scores of the different SETAs (MerSETA, AgriSETA, ServiceSETA, CETA, CHIETA, ESETA and others) for the rate of success, personal development and enhanced employability (). These results indicate that the SETAs show homogeneity, suggesting that the results on learnership outcome and success rate can be generalisable across the SETAs.

Table 3. Test of homogeneity (ANOVA) of the registered SETA.

4.3. Poverty challenges

A 5-point Likert scale was used to determine the poverty challenges (Hair et al., Citation2010), and mean and standard deviation associated with each variable is shown in . Respondents agreed that they have a strong family supporting structure as VAR1 (M = 3.58, SD = 1.21). However, their families are unable to support them financially (VAR2), with some respondents indicating that their families depend on social grants. Respondents highlighted that they worry about bringing in income to support their families, with most using their stipend to support their families (VAR 6) (M = 3.78, SD = 1.17). The respondents were not happy with the stipend received (M = 2.27, SD = 1.18), with most respondents disagreeing with the statement: The cost of travelling to work does not give me any financial strain (M = 2.62, SD = 1.38).

Table 4. Descriptive statistics on poverty challenges.

4.4. Effects of poverty challenges on rate of learnership success

4.4.1. Effect of poverty on rate of learnership success

The effect of poverty challenges on the rate of learnership success was examined in . Model 1 is an ordinary least square (OLS) model that was statistically significant, indicating that this model fits well, compared to the initial model where only F = 8.81, p < 0.01, and this model explained 5.41% ( = 0.0541) of the variance. Poverty challenges were a statistically significant, though negative, predictor of the rate of learnership success, β = −0.294 with t-statistics = −2.97, p < 0.01. This implies that the lower the poverty challenges are, the higher the rate of learnership success. The model specifications confirm that there was no violation of the key assumption of the ordinary least square model with Durbin-Watson, d-statistic = 1.834, Breusch-Pagan / Cook-Weisberg for heteroskedasticity B.P. = 0.51 and Jarque-Bera JB = 5.956 with a p-value of B.P. and J.B. above 5%. The models were reviewed by incorporating the control variables: the socio-demographic and learnership programme structure (Model 3−6).

Table 5. Regression analysis models on effect of poverty challenges on the rate of learnership success.

These control variables support the independent variables, in these models it is evident that the age, the number of dependents, sector of learnership and registered SETA have an influence on the rate of learnership success.

4.4.2. Moderating effects of the personal development and enhanced employability on the relationship between poverty challenges and rate of learnership success

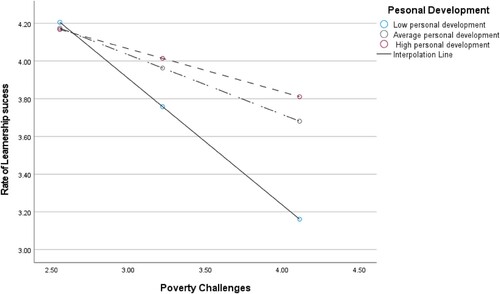

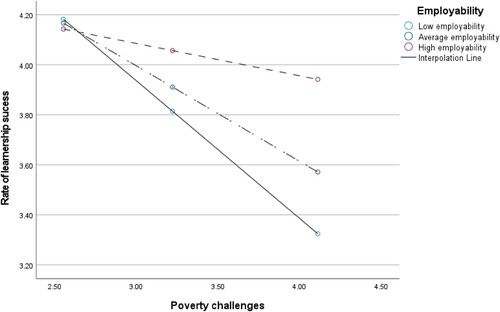

The overall model (Model 7) was statistically significant, indicating that there was a good model fit, F(10 145) = 5.51, p < 0.001 with 27.6% (r2 = 0.276) of the variance due to these predictors, which include the interaction. Personal development was a statistically significant moderator, β = −0.702 (−2,08), p < 0.05, so was the interaction (Int_1), β = 0.2655 (2,51), p < 0.05. The personal development moderator had a buffering effect that decreased the poverty challenges predictor's effect. Model 8 shows that there was also a good model fit, F(10,145) = 5.29, p < 0.001. The enhanced employability moderator was not statistically significant, but the interaction was statistically significant, β = 0.253(2.24), p < 0.05.

Table 6. Conditional effects of the focal predictor at values of the moderator.

The assessment of the conditional effect of the focal point predictor at the values of the moderator () and visualising the conditional effect ( and ) show that at lower personal development, high poverty challenges result in a low rate of learnership success. However, as personal development increase, the rate of success improves even when high poverty challenges coexist. The same pattern is also observed during the higher levels of enhanced employability. This means that high levels of personal development and enhanced employability have a moderating effect on the relationship between poverty challenges and the rate of learnership success.

GPower 3.1 was used in a post hoc test using the F test from linear regression with fixed model and an increasing r2 to determine the adequacy of the sample size. The adequacy of the sample size was based on the overall model (Model 8), r2 = 0.267, which was used to calculate the effective size with Cohen’s D:

The

= 0.364, which indicates medium effect size. The sample size was 156 and this resulted in statistical power (1 – β err prob > 0.99). This indicates an excellent statistical power which is higher than the threshold of 0.8 (Columb & Atkinson, Citation2016; Madjarova et al., Citation2022), confirming the adequacy of the sample size.

5. Discussion

Hays & Reinders (Citation2018) highlight that the significant benefits of upskilling citizens are that it helps address socio-economic challenges such as unemployment, poverty, and inequality in society. This confirms the importance of participating in upskilling initiatives such as the learnership programmes (Dang Kum et al., Citation2014). The study results confirm the critical role of learnerships, with the respondents indicating that it helps with their personal development in communication, improving self-esteem and acquiring new skills. It also adds value by improving their employability by adding value to career development and job function. This underpins the importance of the initiative of learnerships in providing the more advanced skills that can be applied in any occupation (Hays & Reinders, Citation2018). Learnerships introduce innovative ways of learning and has unlocked opportunities for learners who want to advance their careers in different sectors of the economy, facilitated by the opportunity to obtain a South African Qualification Authority (SAQA)-recognised qualification.

However, it is difficult to implement a learnership programme as it requires much time to plan and execute (Dang Kum et al., Citation2014; Botha et al., Citation2023), the administration of the learnership programme can be affected by external factors and, from an operational perspective, implementing learnerships is a complex task (Kraak, Citation2008). Thus, very few SETAs programmes have been successfully implemented (Visser & Kruss, Citation2009; Akbar et al., Citation2016). Focusing on the external factor, it was important to understand the influence of the poverty challenges on the learnership success rate. In addition, it is critical to establish and optimise the linkages and coordination between firms and education and training organisations as a crucial aspect of demand-led skills development. The recognition of the necessity for a ‘collaborative project’ that involves government, corporations, academic institutions, and other entities is important for success. Nevertheless, the significant function of companies has been widely disregarded and requires renewed attention to bridge this gap (Petersen et al., Citation2016).

As a starting point the significant impact of educational achievement in elucidating the disparity in household income lends credence to the adoption of educational attainment as a proxy for human development in the context of South Africa (Friderichs et al., Citation2023). This is important within a developing country such as South Africa, that is highly affected by the ‘triple challenges’ of poverty, unemployment and inequality. Currently, South Africa has the highest poverty levels, with about 60% of the youth living in poverty. This is exacerbated by high unemployment at 32.9% in the first quarter of 2023 (Statistics South Africa, Citation2023) and high inequality with a Gini coefficient of 0.63, the highest inequality in income distribution around the world (Statista, Citation2022). The study revealed that poverty was a statistically significant predictor of the rate of learnership success, indicating that the higher the poverty, the lower the chances of success. This shows the complexity of the issue, as learnership success improves employability and employment decrease poverty, but this is influenced by the learnership success, which is harmed by poverty challenges.

Our findings show that the learners, despite strong family support at home (which is important for success), are not able to secure the necessary financial support to succeed. Rather, these learners are worried about bringing money into their homes where the majority indicated that they use their stipend to support their family. The consequence is that they found the stipend inadequate, and the cost of travelling to work gave them added financial strain. This is congruent with the resources and investment theory which underpinned that poverty comes with many challenges that cause stress (Naven et al., Citation2019).

What is also evident from the study findings is that age, dependents, and sector of learning (public or private) are critical factors to consider when understanding the influence of poverty challenges on the rate of learnership success. Age has also been a huge topic linked to maturity and being responsible. Cavanagh et al. (Citation2020) argue that more mature people demonstrate more responsibility and a certain level of commitment because they must provide for their families. These authors also highlighted with maturity comes experience; however, at the same time older workers has increased responsibilities, with factors such as number of children having an influence women and men’s development and movement in workplace. Cools et al. (Citation2017) observed that the presence of more children leads to significant decreases in the amount of work that women engage in. However, this effect diminishes as the children grow older. The presence of more children decreases the likelihood women being employed by more lucrative companies, their ranking in terms of earnings within the company, and their chances of being the highest earner in the workplace. The career impacts endure much beyond the restoration of labour supply. There is no discernible impact of the number of family members on any of the employment-related outcomes for men, whether it is in the short or long term. Krukowski et al. (Citation2021) also found that there were noticeable differences in academic productivity based on gender and the age of the children, with women more negatively affected than men.

Despite the negative effect of poverty challenges on the rate of learnership success, the results of our study reveal that personal development and enhanced employability improve the rate of success even in high poverty levels. This is congruent with the views of Piketty (Citation2014), who believes that people with advanced skills have a better chance of getting professional jobs and being able to get a decent income to support their households, reducing inequality and poverty in their community. The success and development of the economy are primarily dependent on the level of skills and expertise in the country, making staff the most important asset as there is a positive relationship between human capital and economic growth (Dae-Bong, Citation2009). Ngepah et al. (Citation2021) posit that the effect of skilled employment on economic growth is evident and is congruent to the theoretical literature, as such skilled labour has a favourable impact on economic output and growth in South Africa. This suggests that policy should prioritise the enhancement of the skills of the workforce to facilitate their positive contribution to economic activities that generate value in South Africa. Simply put, government must invest in its people through training and education as this is expected to lead to improved quality of skills in workers, resulting in increased productivity (Mtotywa & Mdlalose, Citation2023a), which leads to economic growth, social stability and better living conditions.

5.1. Theoretical and policy implication of the study

This study contributes to the literature on the impact of poverty as one the ‘triple challenges’ on learnership. This is an under-researched topic, despite learnership system being in operation for the past 20 years as a vital segment of the National Skills Development Strategy. This study contributes towards understanding the dynamics associated with the success of learnership especially in developing countries and form a good basis for policy improvements.

The National Skills Development Plan seeks to ensure that South Africa has adequate, appropriate, high-quality skills that contribute to economic growth, employment creation, and social development. The skill development policy attempts to promote development of human resources skills by empowering unemployed individuals with programmes such as learnerships programmes to develop their skills to be able to add value to the country’s economy. From the study group, 41 persons are below age of 25, and 115 are older than 25 years. This also plausibly explains why 107 individuals have dependents, whereas 49 do not. It is thus possible that learnership might have a better success rate when the group is selected amongst a younger age group, focusing on people with few or no dependants who have reduced financial stress. Also, younger learners will ‘bear the fruits’ for a longer working life. Based on the outcome, it is recommended that policy makers create cohorts of learnership, with higher bias towards 25-year-olds and younger. This should be complemented with recommendations that policymakers decentralise the learnership programme as much as practically possible to substantially decrease the cost of participation in the learnership programme and allow for the mitigation of the influences of socio-demographics such as age and dependents on the success of the learners.

It is also advised that the policymakers optimise the learnership programmes as personal development and value associated with employability to improve individual learner success in spite of poverty challenges. The government can ensure it puts strict measures in place for employers to provide the necessary support to learners by ensuring employers have the right equipment to deliver content to the learners and ensure that learners are not exploited. This can be achieved by regular inspection visits to the educational facilities and creating an anonymous complaint centre where learners can address their concerns without fear of being identified.

Furthermore, the policy makers can consider adding entrepreneurship skills in the learnership programmes as having these skills will prepare learners to be self-employable and decrease the rate of unemployment in South Africa (Mtotywa et al., Citation2023b). These improvements can be made through a partnership between government and private entities. Becker (Citation1993) explains the importance of government and private entities in investing in their people. This investment can be in the form of expenses related to training, education and sharing of new knowledge (Piketty, Citation2014), and distributing knowledge amongst citizens to maintain the high-level wellbeing of society (Marginson, Citation2019).

5.2. Limitations and directions for future study

There are several limitations in this research that provides an opportunity for future research. First, the database of the learners registered for the learnership programme could not be made available; as such, the study had to adopt a non-probability sampling method. Despite this, the responses were adequate, with moderate to large effect size, f2 based on Cohen’s (Citation1988) guidelines and an excellent statistical power. Secondly, with the digital divide being high and high data costs in South Africa, some of the respondents could not be reached practically, i.e. due to resource restrictions, the option of physical (hard copy) distribution of surveys was not feasible. Therefore, the researcher opted for online surveys instead. This hindered the capability of collecting the opinions of non-internet-adopters. Although we have highlighted several control variables, future research might want to explore the variables that drive the Gini coefficient on equality, such as between groups (i.e. race) and within groups (i.e. economic status). Lastly, future research may want to investigate the dynamics moderated by external factors such as digital divide and access to technology, and industry competitiveness of the learnership employer.

6. Conclusions and directions for future research

The overarching research question of the study was: What are the effects of poverty challenges on the learner success rate attending SETA-led learnership programmes in South Africa?

Research findings indicate that the presence of poverty-related difficulties significantly hampers the success in learnership programmes. The outcomes are impacted by socio-demographic and programme structural control variables. This highlights the need to consider the different dynamics beyond the administrative aspect to increase the success of learnership. This especially in developing countries such as South Africa who are highly influenced by poverty and inequality. Despite, this, the personal development and value derived from the learnership moderates this relationship and enhance employability from the learnership programme.

The South African government continue to invest heavily in education, with government expenditure reaching 5% of GDP in the 2021/2022 financial year. This indicates an attempt made by the South African government to invest in its people to eliminate the shortage of skills, as they understand that those with advanced skills have a better chance of getting jobs and being able to get a decent income to support their households, reducing inequality and poverty in their community. This approach is commendable, but it is important to align the learnership programme structure, socio-economic dynamics and the allocation of the resources to ensure that the learnership success is mitigated against the current poverty levels as skill development is at the forefront of improving the employment crisis in South Africa, to alleviate the critical constraints to economic growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 COVID-19: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus, SARS-Cov-2 which causes severe acute respiratory illness in humans (Chitiga-Mabugu et al., Citation2021; Shang & Zhang, Citation2021).

References

- Akanbi, OA, 2016. The growth, poverty and inequality nexus in South Africa: Cointegration and causality analysis. Development Southern Africa 33(2), 166–85. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2015.1120654

- Akbar, K, Vajeth, T & Wissink, H, 2016. The relevance and effectiveness of learnership programs in South Africa: A survey of trainees from within a SETA. International Journal of Educational Sciences 14(1-2), 110–20. doi:10.1080/09751122.2016.11890484

- Anser, MK, Yousaf, Z, Nassani, AA, Alotaibi, SM, Kabbani, A & Zaman, K, 2020. Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures in a panel of 16 countries: Two-step GMM estimates. Journal of Economic Structures 9(1), 1–25. doi:10.1186/s40008-020-00220-6

- Becker, G, 1993. The economic way of looking at behaviour. Journal of Political Economy 101(3), 385–409. doi:10.1086/261880

- Botha, M, Fischer Mogensen, K, Ebrahim, A & Brand, D, 2023. In search of a landing place for persons with disabilities: A critique of South Africa’s skills development programme. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 23(1-2), 163–80. doi:10.1177/13582291231162315

- Bryman, A, Bell, E, Hirchsohn, P, Dos Santos, A, Du Toit, J & Masenge, A, 2014. Research methodology: Business and management contexts. 1st edn. Oxford University Press, Cape Town.

- Cavanagh, T, Kraiger, K & Henry, L, 2020. Age-related changes on the effects of job characteristics on job satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 9(1), 60–84. doi:10.1177/0091415019837996

- Centre for Development and Enterprise, 2017. Business, growth and inclusion: Tackling youth unemployment in cities, towns and townships. https://www.cde.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CDE-Business-Growth-and-inclusion.pdf Accessed 12 August 2021.

- Chitiga-Mabugu, M, Henseler, M, Mabugu, R & Maisonnave, H, 2021. Economic and distributional impact of COVID-19: Evidence from macro-micro modelling of South African economy. South African Journal of Economics 89(1), 82–94.

- Cloete, A, 2015. Youth unemployment in South Africa. A theological reflection through the lens of human dignity. Missionalia 43(3), 513–25. doi:10.7832/43-3-133

- Cohen, J, 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

- Columb, M & Atkinson, M, 2016. Statistical analysis: sample size and power estimations. BJA Education 16(5), 159–161. doi:10.1093/bjaed/mkv034

- Cools, S, Markussen, S & Strøm, M, 2017. Careers: How family size affects parents’ labor market outcomes in the long run. Demography 54, 1773–93. doi:10.1007/s13524-017-0612-0

- Dae-Bong, K, 2009. Human capital and its measurement. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) World Forum on Statistics, Knowledge and Policy. Busan.

- Dang Kum, F, Cowden, R & Karodia, AM, 2014. The impact of training and development on employee performance: A case study of ESCON consulting. Singaporean Journal of Business Economics and Management Studies 3(3), 72–103. doi:10.12816/0010945

- Deloitte, 2023. Global state of the consumer tracker. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/retail-distribution/consumer-behavior-trends-state-of-the-consumer-tracker.html Accessed 12 May 2023.

- De Louw, A, 2009. Efficacy of learnership programmes: An exploratory investigation of learner perceptions in the Cape Peninsula. Cape Town: Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

- Department of Higher Education and Training, 2018. Annual report 2017/18. Public Service Sector Education & Training Authority, 341/2018, 1–102. https://pseta.org. za/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/PSETA-ANNUAL-REPORT-2017-18-NEW-latest-5Nov18- l-1.pdf Accessed 10 April 2023.

- Erasmus, BJ, Loedolff, PVZ, Mda, TV & Nel, PS, 2009. Managing training and development in South Africa. 5th edn. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Erasmus, B, Schenk, H, Maluadzi, M & Grobler, A, 2019. South African human resource management: Theory and practice. 6th edn. Juta & Co Ltd, Cape Town.

- Erikson, MG & Erikson, M, 2019. Learning outcomes and critical thinking – good intentions in conflict. Studies in Higher Education 44(12), 2293–303. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1486813

- Ferreira, L & Rossouw, R, 2016. South Africa’s economic policies on unemployment: A historical analysis of two decades of transition. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences 9(3), 807–32. doi:10.4102/jef.v9i3.72

- Fourie, FC & Burger, P, 2009. How to think and reason in macroeconomics. 3rd edn. Juta & Co Ltd, Cape Town.

- Francis, D & Webster, E, 2019. Poverty and inequality in South Africa: Critical reflections. Development Southern Africa 36(6), 788–802. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2019.1666703

- Friderichs, TJ, Keeton, G & Rogan, M, 2023. Decomposing the impact of human capital on household income inequality in South Africa: Is education a useful measure? Development Southern Africa 40(5), 997–1013. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2022.2163228

- Gebel, M & Gundert, S, 2023. Changes in income poverty risks at the transition from unemployment to employment: Comparing the short-term and medium-term effects of fixed-term and permanent jobs. Social Indicators Research 167(1–3), 507–33. doi:10.1007/s11205-023-03118-5

- George, D & Mallery, P, 2003. Using SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference (4th ed.). London: Pearson Education.

- Graham, L, Williams, L & Chisoro, C, 2019. Barriers to the labour market for unemployed graduates in South Africa. Journal of Education and Work 32(4), 360–76. doi:10.1080/13639080.2019.1620924

- Green, SB, 1991. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis? Multivariate Behavioral Research 26, 499–510. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2603_7

- Grewe, M, Ukpere, W & Rust, A, 2012. The performance of employed and unemployed learners on learnership programmes in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management 6(44), 11128–44.

- Gumede, V, 2021. Revisiting poverty, human development and inequality in democratic South Africa. Indian Journal of Human Development 15(2), 183–99. doi:10.1177/09737030211032961

- Hair, J, Black, WC, Babin, BJ & Anderson, RE, 2010. Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Educational International.

- Hair, JF, Hult, GTM, Ringle, CM, Sarstedt, M, Danks, NP & Ray, S, 2021. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. Cham: Springer.

- Harris, R & Clayton, B, 2019. The current emphasis on learning outcomes. International Journal of Training Research 17(2), 93–7. doi:10.1080/14480220.2019.1644777

- Havnes, A & Prøitz, TS, 2016. Why use learning outcomes in higher education? Exploring the grounds for academic resistance and reclaiming the value of unexpected learning educational assessment. Evaluation and Accountability 28(3), 205–23. doi:10.1007/s11092-016-9243-z

- Hays, J & Reinders, H, 2018. Critical learnership: A new perspective on learning. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 17(1), 1–25. doi:10.26803/ijlter.17.1.1

- Jubane, M, 2020. Strategies for reducing youth unemployment in South Africa. Proceeding of the World Conference on Children and Youth 2(1), 1–11.

- Jyoti, DF, Frongillo, EA & Jones, SJ, 2005. Food insecurity affects school children’s academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. The Journal of Nutrition 135(12), 2831–9. doi:10.1093/jn/135.12.2831

- Keep Climbing, 2017. Learner complaints. https://keepclimbing.co.za/2017/10/20/learnership-internship-and-apprenticeship-complaints/ Accessed 12 April 2021.

- Kingdon, GG & Knight, J, 2004. Unemployment in South Africa: The nature of the beast. World Development, Elsevier 32(3), 391–408.

- Kingdon, G & Knight, J, 2007. Unemployment in South Africa, 1995–2003: Causes, problems and policies. Journal of African Economies 16(5), 813–48. doi:10.1093/jae/ejm016

- Koyana, S & Mason, RB, 2017. Rural entrepreneurship and transformation: The role of learnerships. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 23(5), 734–51. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-07-2016-0207

- Kraak, A, 2008. A critical review of the national skills development strategy in South Africa. Journal of Vocational Education and Training 60(1), 1–18. doi:10.1080/13636820701828762

- Krukowski, RA, Jagsi, R & Cardel, MI, 2021. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Womens Health (Larchmt) 30(3), 341–7. doi:10.1089/jwh.2020.8710

- Le Pere, G, 2020. The fall of the ANC: What next? (Prince Mashele and Mzukisi Qobo). The Strategic Review for Southern Africa 36(2), 225–8.

- Madjarova, SJ, Pareek, A, Eckhardt, CM, Khorana, A, Kunze, KN, Ollivier, M, Karlsson, J, Williams, RJ & Nwachukwu, BU, 2022. Fragility Part I: A guide to understanding statistical power. KneeSurgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 30, 3924–8. doi:10.1007/s00167-022-07188-9

- Makaringe, SC & Khobai, H, 2018. The effect of unemployment on economic growth in South Africa (1994–2016). MPRA Paper. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/85305/ Accessed 18 April 2023.

- Marginson, S, 2019. Limitations of human capital theory. Studies in Higher Education 44(2), 287–301. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1359823

- Marshall, C & Rossman, G, 2016. Designing qualitative research. 6th edn. SAGE, Thousand Oaks.

- Mtotywa, MM, 2019. Conversations with novice researchers. AndsM, East London.

- Mtotywa, MM & Mdlalose, S, 2023a. The influence of assessment on training to improve productivity of construction companies. Problems and Perspectives in Management 21(1), 169–82. doi:10.21511/ppm.21(1).2023.15

- Mtotywa, MM, Seabi, MA, Manqele, TJ, Ngwenya, SP & Moetsi, M, 2023b. Critical factors for restructuring the education system during the era of the fourth industrial revolution in South Africa, Development Southern Africa. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2023.2234399

- Mwakalila, E, 2023. Income inequality: A recipe for youth unemployment in Africa. SN Business & Economics 3(1), 15. doi:10.1007/s43546-022-00394-0

- Naven, L, Egan, J, Sosu, EM & Spencer, S, 2019. The influence of poverty on children’s school experiences: Pupils’ perspectives. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 27(3), 313–31. doi:10.1332/175982719X15622547838659

- Neely, CJ, 2010. Okun’s law: Output and unemployment. Economic Synopses 30(4), 1–2.

- Ngepah, N, Saba, CS & Mabindisa, NG, 2021. Human capital and economic growth in South Africa: A cross-municipality panel data analysis. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 24(1), 1–11. doi:10.4102/sajems.v24i1.3577

- O’Neil, S, Davel, NJ & Holtzhausen, N, 2023. A short report of the value of learnerships from an organisational stakeholder point of view. South African Journal of Human Resource Management/Suid Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur 21(0), a2006. doi:10.4102/sajhrm.v21i0.2006.

- Pabón, FA, Leibbrandt, M, Ranchhod, V & Savage, M, 2021. Piketty comes to South Africa. The British Journal of Sociology 72(1), 106–24. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12808

- Perry, J, 2019. African truth commissions and transitional justice. Lexington Books, New York.

- Petersen, I, Kruss, G, McGrath, S & Gastrow, M, 2016. Bridging skills demand and supply in South Africa: The role of public and private intermediaries. Development Southern Africa 33(3), 407–23. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2016.1156518

- Piketty, T, 2014. Capital in the twenty-first century. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Rankin, N, Roberts, G & Schöer, V, 2014. The success of learnerships? Lessons from South Africa’s training and education programme, World Institute for Development Economic Research.

- Rasool, F & Botha, C, 2011. The nature, extent and effect of skills shortages on skills migration in South Africa. South African Journal of Human Resource Management 9(1), 1–12.

- SETA, 2013. SETA learnerships. https://www.seta-training.co.za/seta-learnerships.html# Accessed 25 August 2021.

- Shang, Y, Li, H & Zhang, R, 2021. Effects of pandemic outbreak on economies: Evidence from business history context. Frontiers in Public Health 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.632043.

- Statista, 2022. 20 countries with the biggest inequality in income distribution worldwide in 2021, based on the Gini index. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264627/ranking-of-the-20-countries-with-the-biggest-inequality-in-income-distribution/#:~:text=Gini%20Index%20%2D%20countries%20with%20the%20biggest%20inequality%20in%20income%20distribution%202021&text=South%20Africa%20had%20the%20highest,in%20second%20and%20third%2C%20respectively Accessed 15 May 2023.

- Statistics South Africa, 2021. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 2. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02112ndQuarter2021.pdf Accessed 25 August 2021.

- Statistics South Africa, 2022. National Poverty Lines 2022. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03101/P031012022.pdf Accessed 17 May 2023.

- Statistics South Africa, 2023. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 1. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q1%202023.pdf Accessed 17 May 2023.

- Takayama, K, 2013. OECD, ‘Key competencies’ and the new challenges of educational inequality. Journal of Curriculum Studies 45(1), 67–80. doi:10.1080/00220272.2012.755711

- Tshishonga, N & Matsiliza, NS, 2021. Addressing the twin challenges of poverty and unemployment through community work programmes in South Africa. African Journal of Development Studies 11(2), 217–35.

- The Presidency, Republic of South Africa, 2015. National youth policy 2015–2020. Pretoria: The Presidency.

- Van Lancker, W & Parolin, Z, 2020. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health 5(5), e243–e244. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0

- Visser, M & Kruss, G, 2009. Learnerships and skills development in South Africa: A shift to prioritise the young unemployed. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 61(3), 357–74. doi:10.1080/13636820903180384

- World Bank, 2013. The World Bank annual report 2013, Washington, DC.

- World Bank, 2020. Measuring poverty. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/measuringpoverty Accessed 30 May 2021.

- World Bank, 2023. South Africa. Key conditions and challenges. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/bae48ff2fefc5a869546775b3f010735-0500062021/related/mpo-zaf.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2023.

- Zizzamia, R, 2020. Is employment a panacea for poverty? A mixed-methods investigation of employment decisions in South Africa. World Development 130, 104938. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104938

- Zungu, LT & Mtshengu, TR, 2023. The twin impacts of income inequality and unemployment on murder crime in African emerging economies: A mixed models approach. Economies 11(2), 58. doi:10.3390/economies11020058