ABSTRACT

In proposing a new conceptual framework that systematises and comprehends the complex dynamics of cultural heritage politics in China, the study takes its inspiration from Chinese scholars who have explored the relevance of Guanxi beyond its immediate business context. While current discourse theory acknowledges that heritage-making entails complex relationships that structure this making, there is as yet no systematic theoretical account of how these relationships co-exist, mediate and transform heritage-making. In developing a relational sociological framework based on the work of John Dewey, the analysis of digital heritage-making includes a case study of Nüshu, the dominant language and culture in villages on the southwestern frontier of China’s Hunan Province. Using netnography, the study analyses a range of online accounts and websites that form part of the heritage-making process. Drawing on rich digital material that includes online competitions, virtual conversations or comments and digital certificates, the findings highlight the need for a more dynamic relational perspective that acknowledges the mutuality of heritage producers and the process of heritage-making. The findings contribute to a sociological account of heritage-making in China and to a more generalist theory of relational sociology.

Introduction

Cultural heritage politics in China has attracted growing research interest across multiple disciplines, including heritage studies, cultural sociology, tourism studies, anthropology, policy analysis and museum studies (for recent overviews, see Maags & Svensson, Citation2018; Silverman & Blumenfield, Citation2013; Wang & Rowlands, Citation2017; Zhu & Maags, Citation2020). The term heritage typically refers to tangible artefacts (buildings, monuments, historical objects) or intangible practices (traditions, rituals, languages) inherited from the past whose cultural value justifies their preservation for future generations (see Harrison, Citation2010). However, this remarkable breadth of topics and disciplines has not been matched by conceptual developments in the field, and even recent attempts to capture this diversity have failed to deliver any broader theoretical framework (see Cheng et al., Citation2021). The present paper takes a tentative step in that direction by enlisting some conceptual resources from pragmatist social theory that may help to open a more coherent conversation across these multiple disciplines. In particular, we address the role of meaning and meaning-making as a common denominator for approaches to heritage – for instance, as natural versus culturally constructed.

These resources may also be of help in clarifying frequently used terms like discourse, contestation and negotiation. Of these, perhaps the strongest theoretical contender is the concept of discourse, which is often loosely associated with French post-structuralism. This term has gained prominence in recent critical debates that challenge the mere ‘finding’ of heritage and instead emphasise its cultural construction (Groote & Haartsen, Citation2008; Harrison, Citation2013). On this view, artefacts, buildings, landscapes and rituals are not themselves heritage objects or agents that act out predetermined intentions but rather acquire cultural value. In that sense, heritage is not culture but adds value to culture. Based on this idea that heritage entails a process of valorisation, researchers no longer view heritage as a mere historical object but instead emphasise its making (see Smith, Citation2006; Weiss, Citation2007; McNamara & Prideaux, Citation2011; Del Marmol et al., Citation2014). Detailed studies have conceptualised this process of valorisation as an interaction between academic experts and policy makers in the conservation, protection and interpretation of historical sites (Aria et al., Citation2014; Bekus, Citation2019). This ‘interactive’ process is dominated by what Bendix et al. (Citation2012) have characterised as heritage regimes; that is, the process of heritage-making is driven largely by institutional actors that include museum and archaeological experts and tourist agencies as well as policy makers. In this top-down model of interaction, these actors possess the resources and expertise to define, naturalise or consecrate heritage sites and artefacts. However, a growing critical response contends that heritage-making should also take account of interactions with non-professionals (Muzaini & Minca, Citation2018; Robertson, Citation2008), and the rise of the Internet and social media reinforces this bottom-up emphasis (Aigner, Citation2016).

To embed this critical approach, scholars introduced broader umbrella concepts like discourse or critical discourse (Parkinson et al., Citation2016; Skilton et al., Citation2014; Smith, Citation2012) to emphasise that heritage must be seen in relational terms rather than as a neutral agent. The idea of heritage-making encompasses the political (memory), commercial (tourism) and scientific (expert) dimensions of heritage as relational. However, in the absence of further theoretical development, the full potential of this relational approach has not yet been realised. For instance, studies of top-down versus bottom-up interactions have depended on discourse analysis to demonstrate how different actors define their positions. This assumes pre-existing dispositions and motivations, shifting agency from the object of heritage-making to the actors involved (Harrison, Citation2015, Citation2018). This means that terms like heritage-making and heritagization (the process of heritage valorisation) are based on an implicit model of social interaction in which interactants X, Y and Z are conceived as interdependent; that is, X is what it is and does what it does because it interacts with Y and Z and because Y and Z do likewise.

Notably, the relational ordering of the social world as a conceptual resource has recently been discussed in a Chinese context by scholars exploring how Guanxi (translated as relationships, networks or connections) might prove useful as a methodological or conceptual tool beyond its usual business role (see Kriz et al., Citation2014). These authors suggest that ideas from relational sociology can help to clarify the complex cultural processes that shape, transform and mediate heritage-related meaning-making (see Kavalski, Citation2016; Shih, Citation2017; Tsang, Citation2011). Building on this view, the present study develops a theoretical framework based on the notions of self-action, inter-action and trans-action developed in Dewey’s later work (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989) and its further conceptualisation by relational sociology (Dépelteau, Citation2008; Emirbayer, Citation1997; Morgner, Citation2019; Selg & Ventsel, Citation2020).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. After elaborating the proposed theoretical framework, we outline the case study methodology. Based on relational netnography, this approach was chosen because it captures voices and positions as outcomes of the dynamic and unfolding relational processes of heritage-making. The empirical case study of Chinese Nüshu culture captures the multiplicity of competing and contested relationships at play in the process of heritage-making (bottom-up versus top-down, online and offline, power relations). In discussing our findings, we highlight the need for a more generalist relational sociology that illuminates heritage-related meaning-making in a Chinese context, with broader application to cultural sociology.

Theoretical framework: substantialist and relational perspectives on heritage

Following Emirbayer (Citation1997), it is common to explicate relational approaches by distinguishing them from their opposite substantialism. The essential question is whether we see the world primarily in terms of relations as unfolding dynamic processes (relationalism) or in terms of static ‘things’ or ‘substances’ (substantialism). To articulate this distinction, Emirbayer (and many others who followed) turned to Dewey and Bentley’s Knowing and the Known (1949) (see for example Dépelteau, Citation2008; Jackson & Nexon, Citation1999; Morgner, Citation2019; Selg & Ventsel, Citation2020). As a significant figure in the field of cultural sociology, Dewey’s Art as Experience and Democracy and Education have been especially well received (see Mattern, Citation1999; Shusterman, Citation2012).Footnote1 However, his later writings on the notion of trans-action have received less attention (see Morgner, Citation2019). Dewey and Bentley introduced this term to distinguish their ideas from common epistemologies and psychological conceptions that insist on a radical separation between observer and observed. According to Dewey and Bentley (Citation1949/1989, p. 96), ‘observer and observed are held in close organization’, and the concept of trans-action emphasised their resistance to the idea that the observed exists either only in someone’s mind or independent of what is actually observed. This ‘unfractured observation’ (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, p. 97) integrates observer and observed as the situation within the observer in which observations arise. They further distinguished between different concepts of social action and their relations as self-action, inter-action and trans-action and illustrated these in terms of known historical states of society. Self-action is associated with Greek city states and the Middle Ages; inter-action is associated with early modern physics; and trans-action refers to the recent past. However, all three forms of relationing are seen to co-exist in reality.

The notion of self-action conceptualises the world ‘in terms of presumptively independent “actors,” “souls,” “minds,” “selves,” “powers” or “forces” taken as activating events’ (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, p. 71). Regarding the association with Greek antiquity, the following Aristotelian explanation is grounded in self-action: ‘From the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule … He who participates in reason enough to apprehend, but not to have, reason, is a slave by nature’ (Politics I, 5). Christians of the Middle Ages also applied the concept of self-action to the human soul (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, p. 124) as establishing a knower ‘in person’.

In our terms, the notion of ‘found’ heritage can be expressed as the self-action of A on B, where actor A (actor, thing) is independent of B, and actor B is structurally determined by A. On this view, heritage is typically understood as a benign naturalised artefact that has intrinsic cultural value. Additional help is required to promote this value – for instance, by framing a site as a destination for tourism or for biological or technical conservation (see Dominguez, Citation1986; Noss, Citation1987; Millar, Citation1989; Marren, Citation1990). References to ‘national heritage’ denote existing traditions and artefacts, approximating the biological meaning of inheritance or ancestry. This is most strongly associated with a substantialist approach, in which heritage is viewed as an essence that exists in its own right.

As an example of the inter-actional view of the world, the Newtonian account of the mechanics of constant motion as uninterrupted by other motions holds that ‘thing is balanced against thing in causal interconnection’ (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, p. 101). Thomas Hobbes, who was familiar with Newton’s thinking, broke with the Aristotelian worldview to formulate perhaps the earliest application of inter-action to social theory. In place of Aristotle’s view of action as the result of continuous application of a force, Hobbes linked action to motion; it is the agent who acts, who is put into motion, who is moved (Hobbes, Citation1839, p. 417). Once in motion, action can only be altered by a motion contrary to that of the first agent. According to Hobbes, what sets an action in motion or activates a passive body is the will or desire to survive. However, this basic instinct sets the actor on a linear path, causing it to inter-act with the paths of other actors subject to the same drive. In a state of nature, says Hobbes, these inter-actions result in war. This account of reaction against action is a common trope that has fascinated later generations of social scientists.

The concept of heritagization typically incorporates an inter-actional perspective. Here, actors A and B are constituted as properties (values, knowledge, power) that are independent of the relations between them. Within this model of discursive forces, heritagization is typically conceived as a process of inter-action between different actors. In a heritage context, this foregrounds decision making and the development of narratives based on political power and archaeological expertise, as well as occasional challenges by non-professionals. Emphasising how these actors and their positions historicise or modify artefacts through meaning-making, heritage is understood as the construction resulting from these interactions (see Bourdeau et al., Citation2016; Ross & Saxena, Citation2019; Waterton & Watson, Citation2013). While emphasising construction, this approach nevertheless relies on substantialism, as for instance in the pre-existing entities that engage in construction through inter-action.

Unlike self-action and inter-action, which are forms of substantialism (Emirbayer, Citation1997; Selg & Ventsel, Citation2020, ch. 2), trans-action entails a thoroughly relational and processual perspective, ‘where systems of description and naming are employed to deal with aspects and phases of action, without final attribution to “elements” or other presumptively detachable or independent “entities,” “essences,” or “realities,” and without isolation of presumptively detachable “relations” from such detachable “elements”’ (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, pp. 101–102). This more recent approach holds that, in the modern world, there is no longer a knower that exists in itself beyond all knowledge and outside time and space (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, p. 127). Under such conditions, life is open to revision; it has a contingent quality, marked by a sense of ‘what if?’ (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, p. 74). For that reason, there is no attribution of ‘essences’ or ‘realities’ to the ‘elements’ captured by our conceptual schemes, and those elements are not detached from relations in which they are embedded (and vice versa). Meaning does not derive from an outside world or from an actor extra mundum. In the modern world, the actor can only be understood in trans-actional terms; for example, there is no ‘businessman’ unless he is participating in a chain of trans-actions referred to as ‘business’.

In a strict sense (see Emirbayer, Citation1997, p. 287), the trans-actional or relational perspective informs accounts of heritage in which neither actor A nor actor B is seen to be independent. In this context, the meaning of an action can only be determined in a recursive network of other actions. This idea is strongly linked to more recent theoretical developments in linguistic network theory or actor-network theory. The concept of heritage assemblages or heritage agencements acknowledges multiple modes of existence and wordling practices (Harrison, Citation2018) and how agency is invoked and distributed across networks that may include human ‘actors’ (anthropologists, indigenous ‘subjecthood’, political actors) and non-human ‘actors’ (websites, computers, film and sound recording instruments). In shifting the focus from particular actors to the set of relations and processes that ‘assemble’ heritage (Harrison, Citation2015; Harrison et al., Citation2016), this does not mean that substantialist meanings will vanish but that they become a relational outcome that only appears as such.

In aligning relational sociology with heritage-making, our aim is to link different forms of relationing to the implicit theoretical notions that underpin heritage research as a first step towards systemising this broad field. While this serves to indicate the robustness of the proposed theoretical framework, it would be misleading to consider self-action, inter-action and trans-action as existing independently. Just as Guanxi emphasises how relations build on each other to generate social complexity, we contend that the proposed framework brings these different approaches into mutual dialogue. For instance, discourse-based approaches tend to reject the notion of ‘found’ heritage. However, one might also question why and how such models of self-action operate in contexts where social reality is treated as a given (see Berger & Luckmann, Citation1967). In that regard, we will explore how self-action, inter-action and trans-action are produced and reproduced and how they relate and influence each other.

Methodology: netnography and relational ethnography

To source our empirical material, we performed a netnography of online virtual platforms related to Nüshu, a language used only by women in villages on the southwestern frontier of China’s Hunan Province. As Nüshu was disseminated through elders’ oral instructions memorised and rehearsed by learners, its use was confined to a specific area, and learning relied on familial and face-to-face interactions. In the 1980s, Nüshu was rediscovered by scholars and local government, and training courses were designed to transfer Nüshu knowledge and skills in school-like settings. This more formal approach raised questions about what should be taught and how to preserve Nüshu authenticity, which in turn prompted broader discussion of Nüshu as heritage. The research extracts presented here focus on folk Nüshu bearers in an interactive digital media context beyond government or academic platforms. These online platforms serve as venues for the transfer of Nüshu knowledge and skills and have also become a major heritage-making resource. The findings presented here are based on long-term observation of the Nüshu virtual community.

As social media and online activities are increasingly integrated into everyday life, netnography or digital ethnography is increasingly used for data collection in the field of heritage studies (Garcia et al., Citation2009). According to Hallett and Barber (Citation2014, p. 307), ‘it is no longer imaginable to conduct ethnography without considering online spaces’. Increasingly, heritage scholars explore how people create their own heritage landscape through rich participation, social relationships and use of mobile phone cameras (Hjorth & Pink, Citation2014, p. 54). Emerging styles of netnography include virtual ethnography (Hine, Citation2000), Internet ethnography (Miller & Slater, Citation2001), cyber-ethnography (Escobar, Citation1994), digital ethnography (Murthy, Citation2008), expanded ethnography (Beneito-Montagut, Citation2011) and ethnography of virtual worlds (Boellstorff et al., Citation2012). This research acknowledges that the online world includes communities that engage in complex social interactions with real-world impacts (Jones, Citation1995; Kavanaugh & Patterson, Citation2001; Komito, Citation1998).

Digital ethnography has been shown to have several advantages, especially when exploring the complex patterns of Web 2.0 or social media platforms beyond the less mobile or dispersed Web 1.0 (Rheingold, Citation1994). This is the main domain of interest for online ethnographers (Postill & Pink, Citation2012), and the approach has proved sufficiently flexible and adaptable to respond to ongoing change in the online environment (Pink et al., Citation2015; Robinson & Schulz, Citation2009).Footnote2 Our netnography is informed by relational or trans-actional ethnography (Burawoy, Citation2017; Desmond, Citation2014). Desmond proposed a relational turn to overcome the substantialism of bounded and predetermined research entities like neighbourhoods, workplaces, gang members or political activists. Rather than bounded groups defined by members’ shared views or organisational boundaries, trans-actional ethnography looks at the relational configurations that constitute an actor or an institution. For present purposes, this amounts to a modest proposal that the study object, setting, participants and other entities all contribute to the construction of the scientific object and that established social categories should not be taken for granted. This approach ‘gives ontological primacy, not to groups or places, but to configurations of relations’ (Desmond, Citation2014, p. 554).

Combining Dewey and Bentley’s notion of trans-action with insights from processual ontology (e.g. Rescher, Citation1996), Jackson and Nexon (Citation1999) distinguished between ‘owned’ and ‘un-owned’ processes: ‘Owned processes are “doings” attributable to a particular “doer”. Un-owned processes are “doings” which are not attributable to a particular “doer”. Processes in substantialist accounts are owned – entities instigate processes [as in self-actionalism], or processes are reified as entities [as in inter-actionalism]’ (Jackson & Nexon, Citation1999, p. 302, italics added). In viewing processes as owned, substantialism entails process-reduction, but a relational/trans-actional approach would view social processes as un-owned. Consequently, we incorporated two methodological points from Selg and Ventsel (Citation2020). First, a relational/trans-actional research strategy should seek to explain social processes without process reduction; that is, social processes like heritage-making should be viewed as ‘un-owned’ rather than ‘owned’. Second, this approach should be able to explain actors, institutions, actions and so on as constituted by these ‘un-owned’ processes; in other words, the elements of social processes and their relations can be considered separately but not as separate (see Selg & Ventsel, Citation2020, pp. 30–35; Selg et al., Citation2021). As trans-action refers to an action that transcends the entities constituted within this action, social processes must be understood as un-owned; no entity can be presumed to own them, as the entities themselves emerge within the process. This is the essence of exploring social processes without process reduction (Elias, Citation1978; Emirbayer, Citation1997; Selg & Ventsel, Citation2020; Selg et al., Citation2021), and netnography and relational ethnography depend on this trans-actional methodology (see also Selg, Citation2020) to trace the set of dynamic unfolding relations that constitute a given phenomenon. The case study described below applies this approach to ask the following research questions.

How did the Nüshu process of relationing come about?

How is the meaning of Nüshu as heritage constituted?

How is this constitution explain through self-action, inter-action and trans-action?

Case selection and data collection

Following an invitation to shadow Nüshu social media users, the study data were collected between 2017 and 2020. These online groups are mostly non-public, with specified entry barriers, but some of these platforms accommodate digital ethnography researchers. To choose the most suitable sites from the many available, we began by mapping all Nüshu online platforms, including Nüshu WeChat and QQ platformsFootnote3 and Nüshu-themed video websites and blogs. In particular, we recorded levels of activity, number of participants, social influence and the extent of available content. After repeated comparison, four online platforms were selected for their high levels of activity, large user numbers, ongoing content updates and breadth of social influence. details the four selected platforms.

Table 1. Selected sites for digital ethnography.

After securing ethical approval, digital ethnographic observation began in March 2017. In approaching these groups, we relied on snowball sampling. The initial research focused on two Nüshu platforms: China’s Nüshu World’s Heritage (中国的女书世界的遗产) and the Long-feet Scripts Nüshu Communication Group (长脚文字女书交流群). From there, links were built to other social media platforms, including QQ and WeChat. The observations included the following elements: (1) online exchanges between members; (2) heritage-making activities and member participation; (3) shared articles and messages, including texts, conversations, debates and images; (4) classifications and constructions of Nüshu heritage activities. In line with the ethnographic approach, tactics included brief interviews and questions about existing practices.

Findings

Un/official social media and the notion of ‘small people’

I choose official accounts to disseminate Nüshu culture because everyone now has WeChat [which] is very popular and is convenient for disseminating Nüshu. Other people can use an app or a website for dissemination, but I don’t have … the ability to develop an app or design a website. WeChat is like self-media; as its slogan says, ‘No matter how small the individual, they can have their own brand’. That is to say, anyone can own an account, making it suitable for both amateurs and professionals. (Indigenous Nüshu Transmitter, Respondent 14, September 2018)

Although interviewees often referred to the users (themselves) of these platforms as ‘small individuals’ (小的个体), this notion of selfhood does not refer simply to self-action as a predetermined identity but expresses that the ‘self’ is a relational construction of participation. Participants frequently used the label ‘small individuals’ (小的个体) to present themselves as of no great importance, implying that their voice cannot change the construction of heritage. However, this smallness makes sense within the context of ‘self-media’ (自媒体) platforms, which can amplify the small and make it bigger. This perspective of ‘self’ expresses the trans-actional presumption that ‘the very terms or units involved in a transaction derive their meaning, significance, and identity from the (changing) functional roles they play within that transaction’ (Emirbayer, Citation1997, p. 287).

This relational ordering of smallness and self-media is a key component in constructing power relations in this setting. In this regard, Margaret Somers (Citation1994, p. 72) wrote that ‘the most significant aspect of a relational setting is that there is no governing entity according to which the whole setting can be categorized; it can only be characterized by deciphering its spatial and network patterns and temporal processes’. To that extent, power is not about someone enforcing certain actions (as in cause and effect) but requires that participants can refer to a relational ordering to symbolise their situation as involving power (see Luhmann, Citation2017). Here, the ‘small individual’ may jeopardise this relational ordering of power by presenting as an ‘underdog’ or one who is likely to lose. However, this also means that any small gain is likely to upset whatever constitutes the situation of power, as the ‘underdog’ did not exist beforehand and does not exist independent of this trans-action. The ‘self’ of the underdog stands in contrast or opposition to other actors in the network and forms part of the heritage assemblage. This is further evidenced by the ‘brand’ construction referred to in the excerpt above, in which the individual can be said to own their own heritage. This is worth noting because, beyond constructing the participant as underdog, this relational arrangement differentiates between the ‘official’ government-approved or employed heritage participants and ‘unofficial’ indigenous persons.

Before the Nüshu Training Course in August 2018, the official had announced that a new batch of ‘Nüshu Transmitters’ would be selected from the trainees, but so far, there has been no outcome. Only seven people have been designated as Nüshu Transmitters since the early 2000s. As a result, many people believe that only seven people currently know Nüshu and that the scripts written by these Nüshu Transmitters are absolutely correct. I'm afraid this is really funny; Nüshu has never belonged to you or me. (Indigenous Nüshu Transmitter, Respondent 14, September 2018)

The government representatives designated as ‘Nüshu Transmitters’ run their own social media accounts and present the approved or official version of the ‘heritage brand’ by registering a series of trademarks and implementing local heritage rules and laws to protect their intellectual property rights (see ). They actively claim ownership and exclusive rights of access to local heritage resources. As a result of this unofficial/official distinction, heritage-making is impacted by the relationing of participants, as some social media accounts claim to represent the verified and authentic approach to Nüshu while others maintain that the unofficial is the undiluted and authentic account.

… We are not willing to deliberately make Nüshu mysterious and secretive. We don't want to make it a ‘huge secret’ (天大的机密) or a ‘throne’ to be inherited (有皇位要继承). ‘Nüshu Transmitter’ is now a title that can only be ‘knighted’ (加封). This ceremony satisfies the self-esteem of the grantor and also stimulates the enthusiasm of the grantees. On the other hand, as you know, when something is rare, it becomes precious. That's why the number of ‘Nüshu Transmitters’ must be strictly controlled. The granting system is an excellent way of monopolising Nüshu's cultural and economic interests. (Indigenous Nüshu Transmitter, Respondent 14, September 2018)

In this context, Nüshu heritage-making is not based on wider social relationships or on the relationing of everyday experiences but is withdrawn from public existence. It is declared to be secretive and mysterious, as something that can only be understood by specialists. As a fixed entity or self-action, it must be protected by an official regulatory scheme that avoids inter-action in order to prevent its alteration and subsequent dilution. This representation of Nüshu as self-action means that it can be treated as an exclusive good or service for financial gain. This also suggests that heritage-making and representations of heritage are not separate entities. Traditionally, representation implies an underlying true self or real essence; in practice, representation combines the notions of self-action and inter-action to express a threefold relationship between representee, representation and its intended public (Waśkiewicz, Citation2010). Based on such a relational ordering, new meanings can emerge as authorisation.

These forms of self-action are typically dismissed by discourse-based approaches but continue to play an important role in heritage-making. For instance, digital platforms like municipal and county government websites (e.g. Yongzhou Municipal Government < yzcity.gov.cn > and the official website of Jiangyong County Government < jiangyong.gov.cn>) present Nüshu in terms of the arrangements, plans, measures and achievements of local heritage departments (see ). This way of disseminating heritage knowledge does not accommodate the conversation and exchange of face-to-face interaction traditionally employed to transfer Nüshu.

This raises a question and a paradox; if Nüshu heritage-making employs other forms of meaning-making that do not overtly rely on heritage as substantial, how can a processual or relational form – something that cannot be owned – be constituted? In this context, a number of WeChat accounts established by local participants were designated as ‘Official’, including Nv Shu Wen Hua (Nüshu Culture) and Nv Shu Chuan Ren (Nüshu Transmitters). Although run by a small number of people, these platforms are the largest in terms of content, which is updated by designated folk Nüshu bearers, using a kind of peer-review system to ensure quality. While this approach has succeeded in bridging the gap between heritage bearers and practitioners without institutional support,Footnote4 it raises the question of how folk Nüshu transmitters can be selected without essentialising them or turning them into self-action. This highlights the role of new digital media, as for instance in the process of selecting folk Nüshu bearers. As well as reflecting on this idea of ‘transmitters’, we will consider the role of relational meaning-making in a more general theory of heritage.

Digital democracy: juries and voting

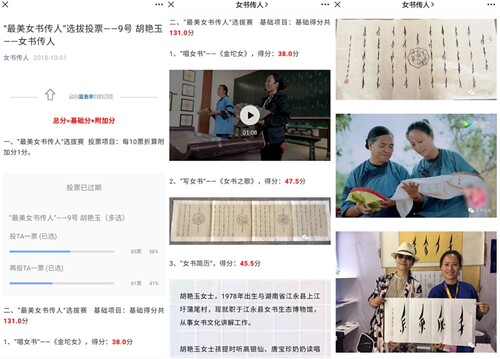

On September 24, 2018, the organisers of Nv Shu Wen Hua (Nüshu Culture) announced a competition to find the Most Beautiful Nüshu Transmitters (最美女书传承人) on several Nüshu social media platforms (see Image 3). The announcement encouraged all Nüshu bearers to participate by submitting three items to showcase their relationship with Nüshu: (1) audio or video recordings demonstrating their ability to sing Nuge; (2) examples of their written Nüshu works using any tools (not restricted to calligraphy brushes or bamboo stick pens; and (3) a biographical account of the candidate's long-term engagement with Nüshu and their personal understanding of Nüshu culture. The first and second items should show the candidate’s mastery of Nüshu knowledge and practices. The third sought evidence of their relationship with Nüshu heritage, their contribution to the development of that heritage, and their participation in the form of photos, documents, artworks, handcrafts and publications.

The submissions were scrutinised by a jury of prestigious Nüshu bearers from the folk heritage society, who assessed candidates’ biographical accounts and their ability to sing and write Nüshu (see ). A candidate’s score on these three items counted as ‘basic points’ – in other words, this was not the final outcome but an inter-action with the judges, who engaged with the applications without making any final decision or declaration. This inter-action between jury and participants then entered the digital public sphere in an online voting call on both platforms. Each candidate was assigned a dedicated voting page to display their Nuge singing, their scripts or calligraphy and their life history account of Nüshu practices. Candidates were also allowed to reach out to more potential voters by forwarding their voting pages to other social platforms. Anyone who viewed these pages was entitled to vote for their chosen candidates during the specified voting period. Every ten online votes counted as one additional point, supplementing the candidate's basic points. To prevent Shua Piao (刷票) or online voting fraud, each voter was only allowed to cast two votes.Footnote5

Figure 3. Screenshots of Most Beautiful Nüshu Transmitters announcement https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/CDdqHkNkouDKGaUOnYxFKA.

The candidate’s total score was calculated as the sum of basic points from the jury and additional points from online voting (see ). The top 50% of participants (those with the highest total scores) were selected as the Most Beautiful Nüshu Transmitters and were awarded honorary certificates. This form of digital democracy attempts to avoid the substantialism associated with official digital accounts by framing Nüshu as a regulated fixed identity independent of inter-action or trans-action. However, in this process of heritage-making, there is no predetermined sense of what constitutes a Nüshu heritage bearer or transmitter. The model of self-action is entangled with inter-actions in the form of peer-review and online voting, and Nüshu heritage does not exist independently but in the trans-actions of social media: ‘small people’, everyday experiences and heritage evaluations that must be explored in greater detail. Furthermore, the trans-action of such meanings should not ignore differences in candidates’ cultural knowledge, contributions to heritage promotion, social capital (e.g. interpersonal relationships on WeChat), professionalism or public opinion cycles, all of which can make a difference. This also reveals a more general process of heritage-making: that essentialist notions do not vanish but become a function of a relational order, constituting identities and points of reference that appear fixed and independent.

Conserving Nüshu through ‘transmission’

The event attracted 27 submissions, which were registered online. Most of the candidates were Jiangyong locals who described themselves as ‘Nüshu hometowners’ (女书家乡人); only four candidates came from other areas, indicating that the process is more attractive and significant for heritage bearers from the indigenous community. The candidates’ social identities were diverse and included farmers, migrant workers, educators, freelancers, housewives, businesswomen, calligraphers, bank staff, medical practitioners, newspapers editors, local Nüshu museum staff and local members of the Communist Party.

I have mastered Nüshu recognition, reading, writing, singing and embroidery, and I am willing to contribute to the inheritance, sharing and promotion of Nüshu culture of my hometown! (Candidate 1, October 7, 2018)

… . Looking at the current potential extinction of Nüshu, out of love for my hometown, I want to take on the mission of inheriting the original ecology of Nüshu culture. To love her, I want to protect her pristine foundation. To love her, I want to maintain her ecological features and plain beauty, and to let this true and natural beauty be passed down from our generation. (Candidate 2, October 10, 2018).

I am an enthusiastic participant in the selection of the ‘Most Beautiful Nüshu Transmitters’. I participate because I am a Nüshu bearer. I would like to continue the transmission of the songs I got from my grandma! Through the platforms of the Official Accounts of Nv Shu Wen Hua (Nüshu Culture) and Nv Shu Chuan Ren (Nüshu Transmitters), I hope that we can spread Nüshu further and carry it forward. (Candidate 3, October 20, 2018)

The above quotes from the submitted online biographies confirm that the main reason for participating in the online event was not to agree what Nüshu is or how it should be defined or to declare themselves as experts. Candidates understood that Nüshu is in flux and does not ‘exist’ as a fixed identity but as something fluid to be passed on or transmitted. This process does not reside in a specific cultural class or elite and is not directed at a specialist audience, and positions are not pre-defined; instead, Nüshu is produced and re-produced through trans-actions. Candidates did not see themselves as full-time or professional Nüshu bearers like the officially authorised heritage transmitters. In this alternative model of heritage-making, participants demonstrated that their Nüshu ability is as good as those seeking to professionalise Nüshu conservation. By showcasing their different areas of expertise, the submissions facilitated comparative evaluation of the works of indigenous and non-indigenous heritage participants (see Image 5).

While the platforms reveal the contrasts between these works, it is more important to recognise their commonality as reflected in the comments, which highlight the works’ shared origins in the nature of their transmission to others (see ). The comments included terms like yuan sheng tai (原生态, original ecology), zhen shi (真实, authenticity, truth), zi ran (自然, natural) and pu shi (朴实, plain), which appear repeatedly in evaluations of Nüshu heritage identity and capability. For example, some noted that the musical works were sung in the same Nuge tones that their grandmother used; that they used the same Jiangyong dialect as the previous generation; or that they still lived in the place where Nüshu originated and still engaged in the indigenous customs and rituals of their Nüshu ancestors (see ).

Figure 5. Example of candidate presentation. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/NTcjGqDl9JwTsWmC1ombPA.

In short, Nüshu music, lifestyle, customs and rituals seem ingrained, and their performance reflects and represents that original ecological cultural heritage. Participants did not view their cultural heritage as artificial, processed or imagined; instead, they felt that Nüshu is characterised by these down-to-earth qualities, which their indigenous community inheritance can preserve. This reminds us that Nüshu culture is not difficult to understand or engage with; as a grassroots culture, it is not decorated or complicated and has not been overwhelmed by modifications. In that sense, a Nüshu community is not merely an object, as the sense of being-together within the same horizon depends on relating closely to others. From a more general theoretical perspective, this implies that ideas of community or culture do not precede the construction of heritage but are themselves an outcome of this process. Digital media offers a platform for this common space as a field of relationing activity that brings these invisible heritage bearers together. These spaces are not mere online showcases or platforms for alternative discourses that counter-act officials and experts. More importantly, as the following chat comments confirm, ordinary users make that space their own by transmitting Nüshu as a common origin and destiny.

I suggest that if you can find two or three like-minded Jiangyong girls, you can experience the oldest and most interesting and valuable Nüshu custom: jie bai jie mei (becoming sworn sisters), and your friendship will last for a lifetime.

Establishing this group is not easy. Friends in the group must be tolerant of each other and must strive for opportunities for mutual cooperation. With cooperation and communication, this group will never die.

I always experience a lot of feelings when I watch your chat every day. With your hard work on the land of Nüshu, there will be a great harvest.

On this WeChat account, I knew many local people who were highly qualified in Nüshu. By listening to and understanding their words, you can gain a deeper understanding of the Nüshu culture.

The digital platform offers a space for reflecting on shared motivations (see online comments above), confronting the same obstacles and being part of the same world (see biographical statements and works in Image 3). This community is not simply about sharing values, nor is it just a discursive battleground for resisting government procedures; it is heritage in action and the actioning of heritage. The community of folk heritage bearers, then, is not seen as an entity or a thing but as ‘a procedure which observes men talking and writing, with their world-behaviors and other representational activities connected with their thing-perceivings and manipulations’ of the ‘whole process’, encompassing ‘inners’ and ‘outers’ (Dewey & Bentley, Citation1949/1989, p. 115). In short, this relational perspective reveals that ideas like community, ownership and bearer are outcomes of the process. As explored below, this inter-action perspective is not a starting point but a trans-actional consequence.

Results: Reflections on ‘Theirs’ and ‘Ours’

This is the first time that our ‘Nüshu people's group (女书人群体)’ ourselves selected Nüshu Transmitters. Being awarded the title of Most Beautiful Nüshu Transmitters means they are selected by folk society (民选女书传人). It is important to highlight the difference between these people and ‘officially-designated’ Nüshu Transmitters(官封传人). The Transmitters we selected can listen, speak, read, write, sing and transmit Nüshu and carry out individual Nüshu research. These people are recognised in our community. (Nüshu WeChat Official Account, December 12, 2018)

Groups are often seen as interest groups, defined by their values, preferences and norms. First elaborated by Dewey’s co-author Bentley (Citation1908), this idea of groups as pre-existing social units has proved influential (see Truman, Citation1951). For Bentley, groups are ‘people in action’ and do not exist independently of others: ‘No group has meaning except in its relations to other groups’ (Citation1908, p. 206). According to the relational perspective advanced here, Bentley’s account aligns with contemporary ideas in dynamic network theory and meaning-making. The above example shows how ‘us’ and ‘them’ accord with Bentley’s relational view rather than existing independently. Once these relational identities are formed, relations between groups are not static. On this view, heritage is a process shaped by ‘groups pressing one another, forming one another, and pushing out new groups and group representatives … . to mediate the adjustments’ (Bentley, Citation1908, p. 269).

Online voting began in early October 2018, and the results were announced on the Nu Shu Wen Hua (Nüshu Culture) and Nu Shu Chuan Ren (Nüshu Transmitters) platforms on December 12, 2018. Ten selected Folk Nüshu Transmitters were awarded the title Most Beautiful Nüshu Transmitter. In addition, nine candidates were awarded the Nüshu Promotional Contribution Award; four were awarded the Nüshu Promotional Encouragement Award; and one person was awarded the title Singing Nüshu Transmitter. Clearly, then, beyond acknowledging the best work, the digital certificate is integral to the making of the Nüshu heritage community.

In distinguishing between folk and official heritage participants, the online event enacted the separation of ‘our’ and ‘their’. However, the social distance so enacted (Bogardus, Citation1926/1927) is not between different people but between different spaces. As noted earlier, the online space supports togetherness, bringing people and all their interests and preferences closer to others in a common space. That shared space of ‘we’ or ‘us’ has no meaning in itself but only to the extent that ‘us’ trans-acts with ‘them’. In that sense, the meaning embodied in a community of common heritage does not derive from an outside world or from an actor extra mundum; without participation, there is no ‘heritage bearer’. Dewey and Bentley (Citation1949/1989, p. 51, 291) understood trans-actional observation as ‘man-in-action’ – that is, as action of and in rather than against an environing world. According to Latour (Citation1996), the making of such communities is not confined to actors but also includes what he called ‘actants’ – non-human subjects with intentional qualities, which in the present context would include virtual trophies and certificates in these online competitions.

We awarded an honorary certificate to every awardee. The significance of the event is that we finally brought together a large number of independent folk Nüshu bearers through the Internet, but this event still entails some regrets. I feel that our power is too weak; we are really tiny. The social impact of this event is also limited. These titles may also be less significant for the awardees. It may provide some temporary warmth, but in the future, it seems likely that they will view these titles as dispensable. (Indigenous Nüshu Transmitter, Respondent 14, December 2019)

The trophies I sponsor will be a few grades higher than the medals granted to designated transmitters by the County Government. The transmitters’ trophies will be just like those in CCTV competitions. I want to build confidence for all Nüshu bearers. I want people to know that Nüshu belongs to folk society. I believe that most Nüshu bearers can contribute to Nüshu without complaint. We just want a little bit of fair treatment. (Indigenous Nüshu Transmitter, Respondent 12, October 2018)

The certificates and trophies are not just silent objects handed out as if independent of the competition. As the quotes imply, the certificate unites the virtual community; it is not just an object but a non-human actant – a further outcome of the network of trans-actional heritage-making. Because they are awarded to all participants, the digital certificates confer commonality rather than social difference (see ). This analysis also reveals the role of objects or materials that do not simply speak for themselves in sense of being able to determine the meaning-making of heritage. In this context, Jacobs and Merriman (Citation2011, p. 216) argued that built material culture is ‘part of an on-going re-design of the world’ and that ‘buildings are fluid entities in the making’. In the context of the present study, this argument can be further developed to suggest a relational mattering of objects or technologies. From a relational perspective, these are not entities that in themselves determine meaning; instead, one might ask how they are involved in the process of heritage-making, how and why they are selected and how they ground this process – for instance, through memory or ritual. In this process, they take on a substantialist fixed materiality (see Darnhofer, Citation2020).Footnote6

Figure 6. WeChat: The Most Beautiful Nüshu Transmitters Awards. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/8V4zQWs1SNUN2BPuTKirRg.

Conclusion

Given the range and diversity of research interest in the politics of cultural heritage in China, scholars from multiple disciplines have noted the need for a unifying conceptual framework (see Bagnall, Citation2003; Tzanelli, Citation2013; Joo, Citation2016; Nettleingham, Citation2018). In addressing that need, the present study had three aims: (1) to develop a framework that systematises the diverse research on heritage-making and the complex social dynamics that shape these developments; (2) to demonstrate how Dewey’s concepts of self-action, inter-action and trans-action inform a relational perspective on heritage-making as meaning-making, in which oppositions such as ‘found’ versus ‘culturally constructed’ heritage should not be be treated in isolation but as part of a relational ordering; and (3) to make a broader contribution to the field of relational sociology.

The proposed framework was inspired by the relational turn and its recognition in the Chinese context. As used here, ‘relational’ is not just a basic analytical concept but implies that social reality is constituted as relation-based (guanxi benwei) (see Ho, Citation2019; Qiang, Citation2016). To develop the argument, we linked this perspective to recent developments in the field of relational sociology (see Selg & Ventsel, Citation2020), where trans-actions, social interactions and conversations constitute (but do not cause) the essential stuff of social life. On this view, relations are not simply another type of object; society does not have relations but rather is relations (see Donati, Citation2012). In declining to posit discrete pre-given units as its essential matter, relational sociology invites broader questions about the various relational orderings that constitute the social world. We applied this sociological perspective to the study of heritage making as a first step towards systematising some of the key discourses that have shaped this field. For instance, research that invokes substantialist notions of heritage (as ‘found’ or ‘natural’) conceives of heritage as self-action. Employing a discourse model, our framework serves to clarify the nature of relational orderings by conceiving of heritage in terms of Deweyan inter-action, emphasising the roles of contestation, negotiation and cooperation in heritage-making. Finally, we systematised approaches that emphasise the processes and practices of heritage assembly by categorising these as trans-actional processes because they do not invoke finite elements.

Building on the concepts of self-action, inter-action and trans-action, our relational framework elucidates implicit assumptions to provide a clearer overview of existing theoretical approaches and the differences between them. In classifying disparate theories of heritage, we further suggested that these must be regarded as complementary rather than distinct for a fuller understanding of relational ordering in heritage-making and how self-action, inter-action and trans-action intersect. This seems a fruitful approach when exploring the complex dynamics of a relation-based social reality, and our case study of Nüshu culture explores these relational dynamics in a Chinese context.

For the case study, we collected detailed empirical material that included interviews, online and offline interactions, official documents and images. Using a relational methodology, we analysed this material to explore the various forms of relational ordering and how they reinforced each other. Understanding these dynamic processes requires more than a mere descriptive classification of types of relational ordering. To capture relational meaning-making in all its forms, it was important not to dismiss anything as irrelevant or naïve; for instance, rather than dismissing claims of authenticity or given heritage, we tried to understand how this form of relational ordering formed part of the network of previous and subsequent processes. We established that claims of ‘found’ or indigenous heritage often involved a mode of self-action, presenting the reality of heritage as something naturally given. In our view, these were not naïve statements but linked to social processes of meaning-making based on authenticity or ownership. Self-action models of heritage often seem paradoxical in claiming that heritage cannot be culturally or socially defined because it is already defined; that is, its meaning is pre-given. This kind of relational ordering must be distinguished from processes that dilute pure or authentic heritage traditions, especially in the context of knowledge transmission and heritage education. Additionally, we found that power relations form part of relational ordering and positioning. Power is not an extra mundum force but we could show that a situation of power is to be constituted to enable such oppositional movements. The discursive inter-action of contestation and negotiation is based on a trans-actional model in which human and non-human actors co-exist in situations where they hold more or less power. We explored this idea in some detail in the case of the ‘underdog’ as a relational outcome of ‘small people’ and ‘self-media’. We considered agency as an attribute of both human and non-human actors and explored this idea in the context of digital interactions like online competitions and digital certificates. Finally, we showed that the Nüshu community is not simply a vehicle for sharing values or a discursive battleground for resisting government procedures. In characterising community as heritage in action and the actioning of heritage, we mean that community is not a transcendent actor that predetermines people’s beliefs and values but is invoked through action and is actively reproduced as a point of reference for orienting further actions. As noted from the outset, this framework has more general application beyond the specific case of Nüshu culture. For example, it invites us to reconsider the role of essentialism and substantialism in this context, to question their fixed status and to ask what role they play in the process of heritage-making. We must also revisit the idea of construction, which typically relies on pre-existing entities such as communities or cultural actors. Contrary to this assumed pre-existence, we showed that such entities are outcomes of a process of meaning-making. Finally, our analysis contributes to a more general theory of relational ordering that takes account of the role of materiality as relational mattering.

Based on this relational methodology, our analysis of the empirical material unravelled the complex dynamics and processes that shape Nüshu culture by integrating relevant conceptual perspectives to demonstrate how different forms of relational ordering contribute to the formation of heritage-related meaning. Our findings suggest that the proposed framework can account for a wide range of social phenomena that are only partially captured by other theoretical approaches. While our case study was confined to a Chinese context, our approach invites wider consideration of relational issues beyond specific locales.

As well as confirming current ideas in relational sociology, the present study invites further scrutiny of how terms like relational constitution and meaning-making are used and combined. Although this issue is notably absent from current work in the field (see Mische, Citation2014; Morgner, Citation2018; Selg, Citation2013 and Citation2022), prominent authors have suggested that meaning-making might usefully be explored in relational terms. For instance, Jeffrey Alexander has acknowledged this more than once, noting for instance that ‘meanings are relational’ (Alexander, Citation2011, p. 89). Others refer to actors ‘moving pragmatically in relation to their meaning systems’ (Reed & Alexander, Citation2009, p. 33). These thoughts align with recent developments in cultural sociology urging further development of a relational perspective on meaning-making (see also Spillman, Citation2020).

In contributing to the development of new modes of research, the study of heritage-making raises the broader issue of how meaning-making as a key sociological construct can be theorised in relational terms. As Jullien (Citation2000) has noted, any such exploration promises to extend and enrich dialogue between scholars from East and West.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christian Morgner

Dr Christian Morgner is senior lecturer at the University of Sheffield, UK. He is working on cultural and creative industries at the intersection of sociology, communication and cultural studies. Culture is not only a focus of his research but is also a conceptual resource that considers notions of practices and networks of meaning-making. To develop this perspective, he has not limited his research to the study of cultural institutions, cultural values and practices, but have also worked on broader, but related, dimensions of culture, such as risk cultures, arts, health, digital cultures, urban culture and heritage. He has previously world at the University of Leicester and held a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship at Hitotsubashi University, Japan worked as a Research Affliate at the University of Cambridge and has also held visiting fellowships at Yale University, University of Lucerne, University of Leuven and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (Paris).

Xihuan Hu

Xihuan Hu (Ph.D. University of Leicester) is now a post-doctoral researcher jointly supported by Zhejiang University City College and Zhejiang University, China. Her research interests include Chinese cultural heritage, heritage identity and discourse, cultural heritage in smart cities and so on.

Mariko Ikeda

Dr Mariko Ikeda is a human geographer at the faculty of Art and Design in University of Tsukuba, Japan and in charge of the master’s and doctoral degree programme of cultural heritage studies in the Graduate school of comprehensive human sciences. She holds a PhD from the same university. Before taking up her current role, she was Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. Her research interests include exploring the role of culture in the social and economic developments and urban transformations with a particular interest in Berlin and other cities in the West and Central European countries. For her work in this area, she has received an award by the Association of Japanese Geographers in 2019.

Peeter Selg

Dr Peeter Selg is Professor of Political Theory in the School of Governance, Law and Society at Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia. His work on power, relational social sciences, and social science methodology has been published among other outlets in Sociological Theory, PS: Political Science & Politics, International Relations, Journal of Political Power, International Review of Sociology, and The Palgrave Handbook of Relational Sociology. His recent book (with Andreas Ventsel) is titled Introducing Relational Political Analysis: Political Semiotics as a Theory and Method (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). He is the editor (with Nick Crossley from the University of Manchester) of the book series ‘Palgrave Studies in Relational Sociology’.

Notes

1 Dewey also visited China (May 1919–July 1921), where he engaged in a cultural exchange of philosophical ideas (see Dewey, Citation2021).

2 The limitations of this approach include the exclusion of those who do not use online media and conversations restricted to face-to-face settings.

3 WeChat and QQ are the most widely used communication platforms in China, where platforms like Facebook or chat forums like WhatsApp are unavailable. WeChat and QQ combine traditional social media accounts with a chat forum. At the time of the study, there were about 1.2 billion WeChat accounts.

4 This strategy has been very successful. In September 2018, the Nv Shu Wen Hua (Nüshu Culture) platform had about 900 active followers. By mid 2019, that number had grown to 1,500, and by January 2020, there were almost two thousand followers. The audience is spread across China but comes mainly from Hunan Province (40%). Some overseas Nüshu participants also follow this platform.

5 Shua Piao (刷票) refers to online voting fraud when participants bypass website restrictions to register repeated votes and to increase voting rates and audience attention.

6 There is potential to explore this idea further, not least because of the shared benefits for relational sociology and new materialism.

References

- Aigner, A. (2016). Heritage-making ‘from below’: The politics of exhibiting architectural heritage on the internet – a case study. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1107615

- Alexander, J. C. (2011). Fact-signs and cultural sociology: How meaning-making liberates the social imagination. Thesis Eleven, 104(1), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513611398623

- Aria, M., Cristofano, M., & Maltese, S. (2014). Development challenges and shared heritage-making processes in southwest Ghana. In P. Basu, & M. Wayne (Eds.), Museum, heritage, and international development (pp. 150–169). Routledge.

- Bagnall, G. (2003). Performance and performativity at heritage sites. Museum and Society, 1(2), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v1i2.17

- Bekus, N. (2019). Transnational circulation of cultural form: Multiple agencies of heritage making. International Journal of Heritage Studies. Advance online publication. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13527258.2019.1652922

- Bendix, R. F., Eggert, A., & Peselmann, A. (eds.). (2012). Heritage regimes and the state. Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Beneito-Montagut, R. (2011). Ethnography goes online: Towards a user-centred methodology to research interpersonal communication on the internet. Qualitative Research, 11(6), 716–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111413368

- Bentley, A. F. (1908). The process of government. A study of social pressures. University of Chicago Press.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality. Penguin Books.

- Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B., Pearce, C., & Taylor, T. L. (2012). Ethnography and virtual worlds: A handbook of method. Princeton University Press.

- Bogardus, E. S. (1926/1927). Social distance between groups. Journal of Applied Sociology, 11, 473–479.

- Bourdeau, L., Gravari-Barbas, M., & Robinson, M. (Eds.) (2016). World heritage, tourism and identity: Inscription and co-production. Routledge.

- Burawoy, M. (2017). On desmond: The limits of spontaneous sociology. Theory and Society, 46(4), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-017-9294-2

- Cheng, L., Yang, J., & Cai, J. (Eds.) (2021). New approach to cultural heritage: Profiling discourse across borders. Springer.

- Darnhofer, I. (2020). Farming from a process-relational perspective: Making openings for change visible. Sociologia Ruralis, 60(2), 505–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12294

- Del Marmol, C., Morell, M., & Chalcraft, J. (2014). The making of heritage: Seduction and disenchantment. Routledge.

- Dépelteau, F. (2008). Relational thinking: A critique of co-deterministic theories of structure and agency. Sociological Theory, 26(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00318.x

- Desmond, M. (2014). Relational ethnography. Theory and Society, 43(5), 547–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-014-9232-5

- Dewey, J. (2021). Lectures in China, 1919–1920. University of Hawaii Press.

- Dewey, J., & Bentley, A. F. (1949/1989). Knowing and the known. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), John Dewey; the later works 1925–1953 (Vol. 16: 1949–1952). University of Southern Illinois Press.

- Dominguez, V. (1986). The marketing of heritage. American Ethnologist, 13(3), 546–555. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1986.13.3.02a00100

- Donati, P. (2012). Relational sociology. A new paradigm for the social sciences. Routledge.

- Elias, N. (1978). What is sociology? Columbia University Press.

- Emirbayer, M. (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 281–317. https://doi.org/10.1086/231209

- Escobar, A. (1994). Welcome to cyberia: Notes on the anthropology of cyberculture [and comments and reply]. Current Anthropology, 35(3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1086/204266

- Garcia, A. C., Standlee, A. I., Bechkoff, J., & Cui, Y. (2009). Ethnographic approaches to the internet and computer-mediated communication. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 38(1), 52–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241607310839

- Groote, P., & Haartsen, T. (2008). The communication of heritage: Creating place identities. In B. Graham, & R. Howard (Eds.), The Ashgate research companion to heritage and identity (pp. 181–194). Ashgate.

- Hallett, R. E., & Barber, K. (2014). Ethnographic research in a cyber era. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 43(3), 306–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241613497749

- Harrison, R. (2010). What is heritage? In R. Harrison (Ed.), Understanding the politics of heritage (pp. 154–196). Manchester University Press.

- Harrison, R. (2013). Heritage. Critical approaches. Routledge.

- Harrison, R. (2015). Beyond “natural” and “cultural” heritage: Toward an ontological politics of heritage in the Age of anthropocene. Heritage & Society, 8(1), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X15Z.00000000036

- Harrison, R. (2018). On heritage ontologies: Rethinking the material worlds of heritage. Anthropological Quarterly, 91(4), 1365–1383. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2018.0068

- Harrison, R., Bartolini, N., DeSilvey, C., Holtorf, C., Lyons, A., Macdonald, S., May, S., Morgan, J., & Penrose, S. (2016). Heritage futures. Archaeology International, 19, 68–72. http://doi.org/10.5334/ai.1912

- Hine, C. (2000). Virtual ethnography. Sage.

- Hjorth, L., & Pink, S. (2014). New visualities and the digital wayfarer: Reconceptualizing camera phone photography and locative media. Mobile Media & Communication, 2(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157913505257

- Ho, T. E. (2019). The relational-turn in international relations theory: Bringing Chinese ideas into mainstream international relations scholarship. American Journal of Chinese Studies, 26(2), 91–106. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45216266?seq=1

- Hobbes, T. (1839).The English works of Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury (Sir William Molesworth, ed.). John Bohn.

- Jackson, P. T., & Nexon, D. H. (1999). Relations before states:. European Journal of International Relations, 5(3), 291–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066199005003002

- Jacobs, J. M., & Merriman, P. (2011). Practising architectures. Social & Cultural Geography, 12(3), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.565884

- Jones, S. (1995). Cybersociety: Computer mediated communication and community. Sage.

- Joo, J. S. (2016). The cultural logic of heritage redevelopment mega-projects: The distillery district in toronto and cheonggyecheon in Seoul [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Yale University.

- Jullien, F. (2000). Detour and access: Strategies of meaning in China and Greece. Zone Books.

- Kavalski, E. (2016). Relationality and Its Chinese characteristics. The China Quarterly, 226, 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741016000606

- Kavanaugh, A. L., & Patterson, S. J. (2001). The impact of community computer networks on social capital and community involvement. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(3), 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640121957312

- Komito, L. (1998). The Net as a foraging society: Flexible communities. The Information Society, 14(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/019722498128908

- Kriz, A., Gummesson, E., & Quazi, A. (2014). Methodology meets culture. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 14(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813493265

- Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt, 47(4), 369–381. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40878163?seq=1

- Luhmann, N. (2017). Trust and power (C. Morgner, & M. King, Eds.). Polity.

- Maags, C., & Svensson, M. (Eds.) (2018). Chinese heritage in the making: Experiences, negotiations and contestations. University of Amsterdam Press.

- Marren, P. (1990). Woodland heritage. David and Charles.

- Mattern, M. (1999). John dewey, art and public life. The Journal of Politics, 61(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647775

- McNamara, K. E., & Prideaux, B. (2011). Experiencing ‘natural’ heritage. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.492852

- Millar, S. (1989). Heritage management for heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 10(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(89)90030-7

- Miller, D., & Slater, D. (2001). The internet: An ethnographic approach. Berg Publishers.

- Mische, A. (2014). Relational sociology, culture, and agency. In J. Scott, & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social network analysis (pp. 80–97). Sage.

- Morgner, C. (2018). The relational meaning-making of riots: Narrative logic and network performance of the London ‘riots.’. In F. Dépelteau (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of relational sociology (pp. 579–600). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morgner, C. (Ed.) (2019). John Dewey and the notion of trans-action. A sociological reply on rethinking relations and social processes. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morgner, C. (Ed.) (2022). The making of meaning: From the individual to social order. Selections from niklas luhmann’s works on semantics and the social structure. Oxford University Press.

- Murthy, D. (2008). Digital ethnography. Sociology, 42(5), 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038508094565

- Muzaini, H., & Minca, C. (2018). After heritage: Critical perspectives on heritage from below. Edward Elgar.

- Nettleingham, D. (2018). Heritage work: The preservations and performances of thames sailing barges. Cultural Sociology, 12(3), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518783380

- Noss, R. F. (1987). From plant communities to landscapes in conservation inventories: A look at the nature conservancy (USA). Biological Conservation, 41(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(87)90045-0

- Parkinson, A., Scott, M., & Redmond, D. (2016). Competing discourses of built heritage: Lay values in Irish conservation planning. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(3), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1121404

- Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., & Tacchi, J. (2015). Digital ethnography: Principles and practice. Sage.

- Postill, J., & Pink, S. (2012). Social media ethnography: The digital researcher in a messy web. Media International Australia, 145(1), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1214500114

- Qiang, G. (2016). Networks of social relations and underground economics: A study on a black market of bicycles in Shanghai. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 2(3), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X16651774

- Reed, I., & Alexander, J. C. (2009). Social science as reading and performance. European Journal of Social Theory, 12(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431008099648

- Rescher, N. (1996). Process metaphysics: An introduction to process philosophy. SUNY Press.

- Rheingold, H. (1994). The virtual community: Connection in a computerised world. Secker and Warburg.

- Robertson, I. J. M. (2008). Heritage from below: Class, social protest and resistance. In B. Graham, & R. Howard (Eds.), The Ashgate research companion to heritage and identity (pp. 143–158). Ashgate.

- Robinson, L., & Schulz, J. (2009). New avenues for sociological inquiry. Sociology, 43(4), 685–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038509105415

- Ross, D., & Saxena, G. (2019). Participative co-creation of archaeological heritage: Case insights on creative tourism in alentejo, Portugal. Annals of Tourism Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102790.

- Selg, P. (2013). The politics of theory and the constitution of meaning. Sociological Theory, 31(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275113479933

- Selg, P. (2020). Causation is not everything: On constitution and trans-actional view of social science methodology. In C. Morgner (Ed.), John Dewey and the notion of trans-action. A sociological reply on rethinking relations and social processes (pp. 31–53). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Selg, P., Klasche, B., & Nõgisto, J. (2021). Wicked problems and sociology: Building a missing bridge through processual relationalism. International Review of Sociology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2022.2035909

- Selg, P., & Ventsel, A. (2020). Introducing relational political analysis: Political semiotics as a theory and method. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shih, C. (2017). The relational turn east and west from Chinese confucianism to balance of relationships. Korean Political Science Review, 51(6), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.18854/kpsr.2017.51.6.005

- Shusterman, R. (2012). Thinking through the body: Essays in somaesthetics. Cambridge University Press.

- Silverman, H., & Blumenfield, T. (2013). Cultural heritage politics in China. Springer.

- Skilton, N., Adams, M., & Gibbs, L. (2014). Conflict in common: Heritage-making in cape york. Australian Geographer, 45(2), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2014.899026

- Smith, L. (2006). Uses of heritage. Routledge.

- Smith, L. (2012). Discourses of heritage: Implications for archaeological community practice. Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. http://journals.openedition.org/nuevomundo/64148

- Somers, M. (1994). Rights, relationality, and membership: Rethinking the making and meaning of citizenship. Law & Social Inquiry, 19(1), 63–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.1994.tb00390.x

- Spillman, L. (2020). What is cultural sociology? Polity Press.

- Truman, D. (1951). The governmental process. Knopf.

- Tsang, K. K. (2011). A theoretical framework of Guanxi dynamics (Chinese version). Chinese Journal of Sociology, 31(4), 96–115. https://www.society.shu.edu.cn/en/y2011/v31/i4/96

- Tzanelli, R. (2013). Heritage in the digital era: Cinematic tourism and the activist cause. Routledge.

- Wang, S.-L., & Rowlands, M. (Eds.) (2017). Making and unmaking heritage value in China. Routledge.

- Waśkiewicz, A. (2010). Representation as social relation. In praise of georg simmel on the centenary of the publication of his essay ‘The stranger’. Polish Sociological Review, 171, 305–317. https://polish-sociological-review.eu/pdf-126768-54412?filename=Representation%20as%20Social.pdf

- Waterton, E., & Watson, S. (Eds.) (2013). Heritage and community engagement: Collaboration or contestation? Routledge.

- Weiss, L. (2007). Heritage-making and political identity. Journal of Social Archaeology, 7(3), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469605307081400

- Zhu, Y., & Maags, C. (Eds.) (2020). Heritage politics in China: The power of the past. Routledge.