ABSTRACT

The ‘standard narrative’ about capitalism and extreme poverty holds that the transition to the former was associated with a staggering reduction of the latter. Recently, this has been strongly called into question by a critical narrative grounded in a battery of non-GDP-based measures of extreme poverty and living standards, such as subsistence welfare ratios, skeletal height data, and famine reports. This critical narrative holds that extreme-poverty conditions were + rare in normal circumstances before the transition to capitalism, and that a significant deterioration amounting to extreme poverty happened in Europe and globally only afterwards. The present paper re-examines the issue, drawing on these and additional non-GDP-based historical sources of living standards, including formerly overlooked cases, such as pre-conquest Aztec Empire and Tokugawa-era Japan. It finds that the standard narrative’s portrayal of the prevalence of extreme poverty before capitalism is indeed mistaken. However, it also takes issue with parts of the critical narrative, mainly the idea that capitalism caused severe deterioration in living standards. On a widely shared definition of capitalism, and a quantitatively demonstrated periodization of the transition, the notion that living standards were generally poor before a society’s transition to capitalism and only started systematically improving afterwards has better support.

Introduction

The emergence and expansion of the modern capitalist economy and economic behavior are widely seen today as being closely associated with, or even causally responsible for, what McCloskey (Citation2017) has called the ‘Great Enrichment’. Capitalist economic institutions, such as widespread market dependence and market competition alongside secure property rights, and capitalist social practices, such as relentless cost-cutting, systematic improvements in labor productivity, and technological innovation-seeking, are nowadays commonly argued both by mainstream economists (see, e.g., the textbook treatments in Cowen & Tabarrok, Citation2018, pp. 511–535; Bowles et al., Citation2017) and various Marxist scholars (e.g. Brenner & Wickham, Citation2007; Isett and Miller, Citation2017; Clegg, Citation2020) to have ignited modern economic growth. The distinctive characteristic of modern growth is the absence of long-run Malthusian stagnation and the presence of a consistent pattern of increases in income per capita (Brenner & Isett, Citation2002; Allen, Citation2011). Though not the only important factor, this shift is arguably at the root of sustained increases in modern living standards (Allen, Citation2011).

Many scholars have noted the close correlation that exists between increases in GDP per capita and reductions in extreme poverty, calculated with the new ‘cost of basic needs’ approach, both at the world average level as well as across individual world regions (Roser, Citation2021; Moatsos, Citation2021; see also Pinker, Citation2018). The regression coefficient between GDP growth and share in extreme poverty has been stronger than -0.5 in the typical year between early 19th and early twenty-first century (Moatsos, Citation2021), and its average for the whole period is -0.59. In 1820, around 76% of world population was below the basic-needs poverty threshold, while in 2018 only 10% remains so (Moatsos, Citation2021). Some have termed this the ‘standard narrative’ about poverty and the modern economy (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023). The standard narrative holds that extreme poverty had been widespread before the emergence of capitalism and only improved systematically with its onset.

An additional element of the standard narrative about economic development and poverty reduction has been the claim that with the transition to capitalism and modern growth, age-old practices of territorial, imperial conquest and plunder have (slowly) started receding. Again, surprisingly, both non-Marxist (McCloskey, Citation2011; Pinker, Citation2012; Gat, Citation2017; Van der Vossen & Brennan, Citation2018) and Marxist scholars (Wood, Citation2003; Teschke, Citation2003; Lacher, Citation2006; Brenner, Citation2007) have argued that the capitalist economic system and modern growth are either at loggerheads with imperialist conquest or at least make it structurally possible – even likely – that economically motivated territorial imperialism ends.

At the same time, recent years have seen a thoroughgoing re-evaluation of this seeming longstanding consensus. Just recently, a widely acclaimed study by Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023) has provided a strong challenge to the standard narrative, charging that before the emergence of capitalism, extreme poverty had been virtually non-existent or rare while capitalist development was, at least before the creation of widespread trade unions, democracy, and the welfare state in the twentieth century, catastrophic for living standards of the vast majority of people in Europe and globally. Moreover, it has been argued that far from creating the conditions for preventing it, precocious European capitalist development in fact fundamentally benefited from, or even necessarily structurally required, imperialist plunder (Habib, Citation1995; Anievas & Nisancioglu, Citation2015; Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023). Relatedly, some among the ‘New Historians of Capitalism’ (Johnson, Citation2013; Baptist, Citation2014; Beckert, Citation2015) have claimed that violent economic institutions such as plantation slavery had been ‘absolutely necessary’ if ‘the Western world was to burst out of the 10.000-year Malthusian cycle of agriculture’ (Baptist, Citation2014, p. 130). Even as they have not been willing to precisely define capitalism, they nevertheless forcefully argue that systemic violence, robbery, and coercion on an international scale were necessary to the birth of the capitalist economy (see the review in Clegg, Citation2015).

This paper seeks to address and re-examine these foundational issues, especially the connection between capitalism and extreme poverty (including their ostensible indirect connection via colonialism), with the intention of helping to resolve the existing disagreement where possible. The paper’s starting point is the new wide-ranging, systematic, and challenging study by Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023), the importance of which this paper acknowledges and takes as its starting point. The paper improves upon Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023) and contributes to the literature in three key areas: (1) checking the robustness of their findings on the basis of a different, more common definition and quantitatively verifiable periodization of capitalism; (2) analyzing many additional sources and measures of living standards, including data for the important cases of Tokugawa- and Meiji-era Japan and preconquest-era Aztec Empire, which did not appear in Sullivan and Hickel’s study (the data for the Aztecs were not available at that time, for example); and (3) explicating and examining in detail the contingent causal/conceptual connection between capitalism and colonialism, which Sullivan and Hickel presuppose as inherent.

Research design

At its core, this paper follows the research design proposed by Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023). Their central methodological proposition is to examine social living standards before and after the emergence of capitalism, and to do so with reliance on better-quality data than classic estimates of population shares in extreme poverty which rely on inferences from historical GDP reconstructions. They argue that relying on GDP-based poverty figures is problematic, because among other reasons they fail ‘to adequately account for non-commodity forms of provisioning, such as subsistence farming, foraging, and access to commons,’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 2) which means that poverty before capitalism measured in such a way would be overestimated. They further note that GDP-based extreme poverty data are available only for the historical period after 1820, but because the transition to capitalism had arguably happened long before that, these data cannot be used for inferences about precapitalist living standards. In short, more reliable measures of historical poverty would be desirable to verify the standard narrative about capitalism and extreme poverty.

Relying on the work of Allen (Citation2001, Citation2020) and others, Sullivan and Hickel centrally argue that to better assess the standard narrative, we should look back further in time beyond 1820 and focus on data for real wages received by common, unskilled laborers. If it turns out that even this underprivileged stratum of precapitalist society typically received wages high enough to meet or exceed basic subsistence, the standard narrative that extreme poverty was omnipresent is falsified. Moreover, they say we should also draw on other measures of living standards, such as skeletal-based data of height and number and length of famines to gain a fuller insight.

After performing such a re-examination, Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023, p. 14) conclude that ‘the standard public narrative about the history of human welfare’ is not supported by the ‘extant data on wages, height, and mortality’. They add that, ‘Far from a normal or natural condition, extreme destitution is a sign of severe social and economic distress.’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 14) Most crucially, they find that ‘data on wages, human height and mortality indicate that the rise and expansion of the capitalist world-system from circa 1500 caused a decline in nutritional standards and health outcomes.’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 14) They are not the only ones reaching the conclusion that the standard narrative’s claim of omnipresent extreme poverty in the past is unwarranted. A crucial quantitative source they rely on, namely, Robert Allen, likewise suggests that welfare-ratio data contradict the idea of historical extreme poverty being present everywhere and in the large majority of the population (Allen, Citation2020).

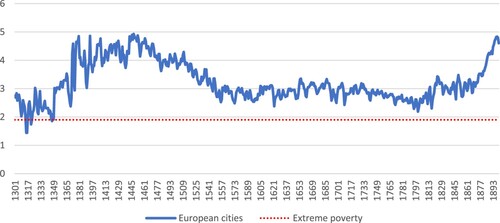

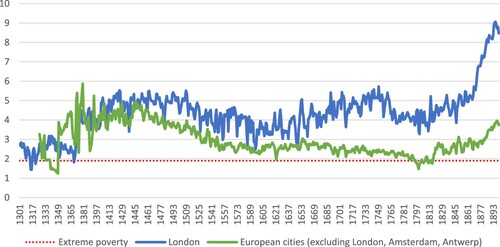

Consider , for instance, which plots the average real daily income – calculated on the basis of the average welfare ratio (i.e. the ratio between historically situated cost of goods needed for meeting basic human needs and real wages; for more see notes in the Appendix) – for unskilled urban European laborers between the 1300s and 1800s. If, as Sullivan and Hickel presuppose, capitalism across Europe is seen as starting to emerge in the long sixteenth century, then it follows that in the precapitalist past, living standards were clearly above subsistence (save for the early part of the fourteenth century, in which Europe had been hit with a series of catastrophic famines). At the same time, with the emergence and spread of capitalism after the late 1400s, living standards deteriorated – although never plummeting to or below extreme poverty levels – and stayed there up until the late nineteenth century. This is almost the reverse of the standard narrative about extreme poverty.

Figure 1. Real daily income per person in a family of four with one working as an unskilled laborer (2011 welfare-adjusted PPP $), 1301-1900. Source: original ‘respectability’ welfare ratios from Allen (Citation2001) for unskilled laborers; for the source of the complete numerical sample see the note on data sources in the Appendix. ‘Respectability’ welfare ratios have been recalculated in two ways. First, to reflect 4.2 consumption baskets (instead of 3.15) in line with Allen (Citation2015) and Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023). Second, to transform them into real daily income for purposes of extreme-poverty comparisons, they have been further recalculated in line with Sullivan and Hickel’s (Citation2023) note, namely, Allen’s original figures have been multiplied by 4.33.

Undoubtedly, such a simple comparison is not by itself enough to establish that capitalism was causally responsible for the ostensible decline of living standards. Mere correlation is not causation. But if the standard narrative itself mostly depends on a mere correlation, i.e., the alleged prevalence of extreme poverty before capitalism and its decline and even disappearance afterward, then it seems fair for Sullivan and Hickel to criticize that view by demonstrating the opposite.

This paper follows Sullivan and Hickel both in method (i.e., comparisons before/after) and substance (i.e., relying on more robust measures of living standards). However, it also seeks to improve upon their study in three key ways. First, in contrast to Sullivan and Hickel, this paper's proposed definition and periodization of capitalism attempt to be more theoretically unpacked and empirically demonstrated. Instead of merely pointing to a particular scholarly literature’s conclusion about when capitalism started, namely, the Marxist world-systems perspective, as Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023, p. 3) do in a single paragraph, this paper strives to itself quantitatively demonstrate when and where capitalism began in Europe. Moreover, this paper’s definition of capitalism and grounding in the existing scholarly literature aims to be more broad and synthetically minded. Instead of primarily relying on one kind of (mostly Marxist-based) scholarship, this paper examines whether a variety of perspectives, such as neoclassical economics, institutional economics, economic history, and also contemporary strands of Marxism (especially ‘political Marxism’), can come to at least a rough definitional agreement about capitalism and modern economic growth.

Second, this paper draws on additional sets of sources and measures of living standards. It incorporates, re-examines, and reinterprets the data drawn on by Sullivan and Hickel, but it also considers additional available data that have not appeared in their paper, such as long-run and even prehistorical male height data, data for adult-only life expectancy, and data on real wages of skilled artisans, with the intention of presenting a fuller context and enabling better comparisons. Furthermore, the present paper analyses the crucial examples of pre-modern and early-modern Japan and pre-conquest Aztec Empire, which did not appear in Sullivan and Hickel’s study.

Third, instead of supposing that poor living standards in colonized areas of the world outside Europe were causally or conceptually tied to capitalism (via European colonialism after the sixteenth century as posited by world-systems theory), this paper seeks to examine the reasons for and against such a (in principle contingent, not given) connection. The paper proposes, and both theoretically and empirically examines, four general sets of arguments that could plausibly tie colonialism to capitalism. It does not deny that colonialism was both associated with, and causally responsible for, violence, brutality, destruction, and poverty in the affected regions, but it questions under which conditions this connection can be said to reflect the institutions or social forces of capitalism – as defined in the present study – specifically.

Defining capitalism and quantitatively periodizing its emergence

Comparing living standards before and after capitalism clearly requires an ‘appropriate’, non-arbitrary definition of the system. Providing such a definition, however, is beset by at least two kinds of problems that have to be addressed. First and formally, definitions are tautologies, which means that in at least one important sense they cannot be more or less ‘appropriate’, i.e., true or untrue. In principle, one could equate capitalism with whatever economic (or even non-economic) characteristic one wishes. There are no empirical tests that reveal how one ought to define a particular phenomenon.

More substantively speaking, the second issue is that the existing scholarly literature itself is not in complete agreement as to how capitalism should be defined. Clegg (Citation2020) presents three contemporary definitional clusters that commonly appear in the historical and social scientific literature, which seem to be either at odds with each other or only imperfectly overlapping. First, some define a capitalist society as one ‘in which production tends to be orientated towards exchange and monetary profit.’ (Clegg, Citation2020, p. 77) This is a broad definition that equates capitalism simply with markets and economic gain, phenomena which have existed in various societies for millennia to a smaller or larger extent (for a critical treatment see Wood, Citation2017). The second definition proposes, much more narrowly, that a ‘capitalist society is one in which the means of production are (a) privately owned by a class of capitalists (b) to whom the direct producers must sell their labor.’ (Clegg, Citation2020, p. 77) This – i.e., the existence of secure property rights, a capitalist class, and a class of dispossessed workers – would be a comparatively much more recent social occurrence. Lastly, some argue that capitalism exists wherever social ‘elites and institutions are characterized by a “bourgeois culture” or “capitalist mindset,” variously described as “frugal,” “rational,” [and] “calculating”.’ (Clegg, Citation2020, p. 77)

Importantly for present purposes, there is more and more agreement among scholars of many different paradigmatic and ideological persuasions (cited below) around the second and third definition, which overlap to a significant degree. What distinguishes a modern capitalist economy from a premodern, precapitalist economy is the breaking out of Malthusian cycles of extensive growth, stagnation, and decline that have characterized human societies for millennia since the Neolithic revolution, and the emergence of systematic economic dynamism and intensive growth exhibited in the famous ‘hockey stick’ graph, which depicts a sudden, almost completely vertical increase in the GDP per capita curve after millennia of virtual stagnation. General agreement about this exists among many contemporary neoclassical economists (see textbooks such as Cowen & Tabarrok, Citation2018; Bowles et al., Citation2017), institutional economists (North et al., Citation2009; Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012), notable Marxist historians and historical sociologists (Wood, Citation2017; Brenner & Isett, Citation2002; Teschke, Citation2003; Brenner, Citation2007; Žmolek, Citation2014; Dimmock, Citation2015; Isett & Miller, 2017; Lafrance & Post, Citation2019; Clegg, Citation2020; Wickham, Citation2021), libertarian philosophers and economists (Brennan and van der Vossen, 2018; McCloskey, Citation2017), and economic historians (Allen, Citation2011). The economic institutions or structures which this diverse literature points out as principally responsible for generating the modern, intensive type of long-run, self-sustaining economic growth are foremost market competition between economic actors (not just markets in themselves), widespread market dependence of these economic actors (instead of the majority of producers being shielded both from market competition and market dependence through the institution of small-scale subsistence farming), and secure rights of private property. These structural characteristics induce or incentivize economic actors to systematically invest in, and uncover, technological innovations; they also systematically pressure them to cut production costs so as to be able to outcompete rivals. This, in turn, results in systematic improvements in labor productivity, which unleashes ‘endless growth’ or sustained increases in GDP per capita decade-on-decade, century-on-century. For more on this paper’s approach to capitalism, see Section VIII in the Appendix.

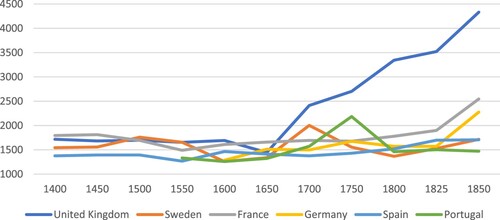

The present paper takes the pattern of ‘endless growth’, or sustained increases in output per capita, as the principal outcome, or symptom, characteristic of capitalism, with the institutions and practices enumerated above forming the core mechanisms or behaviors responsible for that outcome and underlying it. To precisely periodize the pre-capitalist and capitalist era, one would need to look for signs of capitalism in one or the other sense (i.e., as an outcome or as a set of mechanisms). The quantitatively most elegant and clear way is to look at historic figures of GDP per capita. Extensive, precapitalist growth does not produce constant, decade-on-decade, or even century-on-century, increases in GDP per capita, while intensive, capitalist growth does. presents the data for a wide selection of European countries between 1400 and 1800, around the centuries capitalism is commonly dated to (Sullivan and Hickel, for instance, date it to the long sixteenth century).

Figure 2. GDP per capita in selected European countries, 1400–1850 (expressed in international-$ at 2011 prices). Source: the Maddison Project Database 2020 in Bolt and van Zanden (Citation2020).

It can be seen that, with the clear exception of England/UK, none of the shown European countries exhibited the characteristic ‘endless growth’ associated with capitalism in the centuries between 1400 and 1800. The transition to capitalism in the early modern period was not a Europe-wide phenomenon. With the additional possible exception of the Netherlands (to which I turn below), the early-modern capitalist revolution was limited to England alone, and it became visible in the seventeenth century (its origins go further back to the 15th and sixteenth century, see Brenner, Citation2007; Dimmock, Citation2015; Miller and Isett, 2017). It was only in the first half of the nineteenth century that France and Germany witnessed their own capitalist take-off, while Sweden and Spain had to wait for their own turn after 1850 (Portugal was an even bigger laggard, witnessing the start of ‘endless growth’ in the first decades of the twentieth century).

What about other richer parts of Europe not depicted here? Italy, which is not shown in the graph, was economically completely stagnant between 1400 and 1800; in fact, its GDP per capita in 1800 was around 15% smaller than in 1400 (Bolt & van Zanden, Citation2020). Belgium, too, was completely stagnant between 1500 and 1800 (Bolt and van Zanden, Citation2020). These two trading superpowers were richer in absolute terms throughout the period, with both of their per capita GDP figures hovering slightly above $2,000, but they did not experience any signs of ‘endless growth’ until the second half of nineteenth century.

Finally, the Netherlands offers a peculiar case. Arguably, it (not England) was the first capitalist society, breaking through the Malthusian barrier already around the years 1500–1600 (see the disagreement between Brenner, Citation2001 and Wood, Citation2002; see also de Vries & van der Woude, Citation1997; Prak & van Zanden, Citation2023). However, if this really was the first capitalist transition, it also stalled out soon after it began. The Netherlands economically stagnated between late 16th and mid-eighteenth century, its GDP per capita constantly oscillating around the $4,000 mark. A truly uninterrupted Dutch take-off towards ‘endless growth’ only began, or resumed, within the eighteenth century.

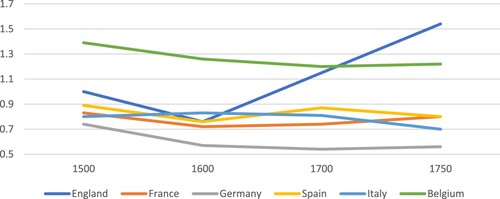

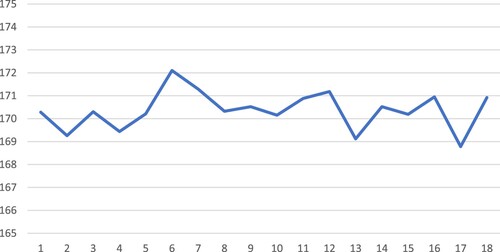

In the precapitalist past, economic growth did not exhibit the modern pattern of ‘endless growth’ principally because large and especially sustained increases in labor productivity were very rare, which was itself a function of very slow and mostly one-off improvements in technology (Brenner, Citation2007; Allen, Citation2011; Isett and Miller, 2017; Wickham, Citation2021). Without regular increases in labor productivity, or productive efficiency, economic output can only grow through increases in labor input. This means that the total GDP of a society can increase, but it increases more or less in line with increases in population, which makes a significant long-run and continuous rise in GDP per capita unlikely if not impossible. This means that if between 1500 and 1800 England, but not other European economies, was really witnessing a capitalist transformation and exhibiting a pattern of post-Malthusian ‘endless growth’, one should be able to see this in its, but not other countries’, productivity trajectory. presents the data.

Figure 3. Output per worker (productivity) in selected European economies, 1500–1750 (1 = English productivity in 1500). Source: Allen (Citation2000).

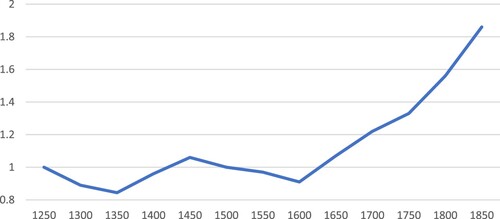

The data show England clearly pulling away from the rest from 1600 on. Other countries exhibit the same pattern of stagnating productivity throughout the period. The only other exception is the Netherlands (Belgium’s productivity is comparatively higher in 1500, but then collapses in the following three centuries instead of constantly increasing). A new quantitative estimation of England’s productivity in this timeframe by Bouscasse et al. (Citation2021), who use a wider measure, similarly puts England’s productivity growth take-off around the year 1600 (see ).

Figure 4. Permanent component of productivity (England), 1250-1850. Source: Bouscasse et al. (Citation2021).

A striking comparison is also evoked by the evolution of farm sizes and productivity between the clearly precapitalist China and early-modern England, as seen in and below. In early-modern England, average farm sizes no longer correspond to that of a smallholding peasantry (5–10 acres) but are instead much larger, amounting to 72 acres around the year 1600. Furthermore, there is no evidence of the precapitalist pattern of long-term fragmentation of holdings (Brenner, Citation2007). Instead, farms are being consolidated and are increasing in size throughout the centuries. In China, however, one can see the distinct precapitalist patter of small farm sizes, with the trend being towards long-term fragmentation. The same patterns can be seen in the evolution of productivity: in England away from stagnation or decline and toward sustained long-term increases, while in China productivity either declines or stagnates over the long term.

Table 1. Average farm sizes in England, China, and the Yangzi delta, 1300–1850 (acres).

Table 2. Grain output per capita (productivity) in the Big Yangzi delta and China.

Other plausible indicators of modern, intensive, self-sustaining economic growth presented in the Appendix (Figures 1a and 2a) likewise suggest that England alone (with the plausible exception of the Netherlands) was undergoing a tremendous socio-economic transformation between 1500 and 1800, while the rest of Europe remained firmly mired in premodern, precapitalist Malthusian conditions until at least the early nineteenth century (see also more detailed comparisons in Isett and Miller, 2017; and individual case studies in Lafrance & Post, Citation2019)

Outline of the major substantive contentions: both for and against the critical narrative

Sullivan and Hickel’s (Citation2023) research has generated four interesting main claims about the historical dynamics of extreme poverty and capitalism, which the present study aims to reexamine in light of its different definition and periodization of capitalism.

First, Sullivan and Hickel say ‘it is unlikely that 90% of the global population lived in extreme poverty prior to the rise of the capitalist system.’ They arrive at this conclusion based on their empirical analysis, which clearly contradicts the standard narrative. Second, refuting the standard narrative’s claim that extreme poverty was once omnipresent, they aim to estimate its actual prevalence. They point out that, ‘Extreme poverty seems to arise predominantly in periods of severe social and economic distress … [E]xtreme poverty is a symptom of social dislocation and displacement. … [R]elatively rare under normal circumstances’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 1, 3, 14). Third, looking to explain why extreme poverty apparently rose in the early-modern period, they argue that it was specifically the ‘rise of capitalism [that] caused a dramatic deterioration of human welfare.’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 1) Fourth, they additionally explain that

in those regions where progress has occurred (as opposed to recovery from an earlier period of immiseration), it began much later [namely, not with the transition to capitalism] … In the core regions of Northwest Europe, welfare standards began to improve in the 1880s, four centuries after the emergence of capitalism. In the periphery and semi-periphery, progress began in the mid-20th century.

This paper agrees with Sullivan and Hickel’s first conclusion. There is presently simply too little data to establish even a very rough estimate of the percentage of global population in extreme poverty before the nineteenth century (though data exist for individual cases, such as England), so pointing to a 70%, 80%, or 90% extreme-poverty share will not do. However, putting the question of unknowable population percentages aside, there is some income data clearly indicating for various regions (such as Europe or Northern India, say) that extreme poverty was typically avoided even at the bottom of the social ladder, namely, among unskilled laborers. This at least suggests that the share of population in extreme poverty (in these regions) was low, and definitely nowhere near 90%. At the same time, these same data in other regions show clear signs of extreme poverty among unskilled laborers, suggesting that extreme poverty (in these regions) might have been relatively high (although again unlikely to be 90% without additional context). Moreover, other, non-income-based data – such as life-expectancy data, famine frequencies, and skeletal heights –, suggest very harsh historical living standards, though not necessarily extreme-poverty level standards, across different regions (including Europe) and with relative constancy through long time periods. In other words, Sullivan and Hickel’s (Citation2023) correct conclusion that it is unlikely that 90% of the global population lived in extreme poverty before the nineteenth century could be (but should not be) naively mistaken for the idea that typical historical living standards were, if not idyllic, at least moderately acceptable. This is definitely not the case, and Sullivan and Hickel never say otherwise.

This latter point ties in with the second conclusion outlined above. The present paper mostly agrees but in part also disagrees with the second conclusion above, depending on how strongly the statements ‘relatively rare under normal circumstances’ and ‘extreme poverty [being] a symptom of social dislocation’ are asserted or interpreted. Crucially, although Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023, p. 14) would themselves recognize that extreme poverty is not solely the ‘sign of severe social dislocation, relatively rare under normal circumstances’ – that is, they are careful to say extreme poverty is only predominantly such a sign – this paper presents somewhat more evidence than them that extreme poverty might in at least certain places (and for parts of the population) be relatively common even under fairly normal circumstances.

The third conclusion above is the one most clearly contested by the present paper. I provide a very different interpretation of the historical data during times of transitioning to capitalism. In contrast to Sullivan and Hickel, I argue the transition to capitalism in Europe was in most terms not associated with deteriorating standards. Moreover, I argue that extreme-poverty conditions outside Europe during the early-modern period cannot be easily or unequivocally tied to capitalism via the mechanism of colonialism, as otherwise argued by Sullivan and Hickel. At the same time, I also provide some reasons to think that the connection between capitalism and extreme poverty through the conduit of colonialism is not wholly unconvincing in certain respects.

My contention, as just outlined, is also connected to the fourth main conclusion presented above. In contrast to Sullivan and Hickel, I show that in most regions, the transition to capitalism as defined by the present paper was associated with robust or improving standards of living (as compared to the pre-capitalist baseline outside of non-typical income shocks, such as in Europe during the Plague).

There is one more clarification that needs to be made. Even though I mostly disagree with Sullivan and Hickel about capitalism causing deteriorating living conditions, this does not mean that I accept a naïve view of the causes of typically low living standards in the pre-capitalist past. Specifically, I do not think the social dynamics of pre-capitalist economies were ‘natural’, or simply given; that is, the result of some inevitable demographic laws. Instead, I see social dynamics both under capitalism and pre-capitalist farming societies as the result of particular social institutions incentivizing human behavior and consequently resulting in larger overarching social trends and patterns (see Brenner, Citation2007, for a Marxist perspective along these lines, or Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012, for an institutional-economics perspective along the same). Extractive and subsistence-based institutions and practices, such as serfdom, slavery, self-reliant, small-scale peasant farming and the subdivision or fragmentation of plots of land, absence of market competition and free entry into the market, etc., characterize most pre-capitalist farming societies (for a broad, textbook-like treatment, see Isett and Miller, 2017). Under such social conditions, intensive growth (resulting in sustained increases in output per capita) based on constant increases in labor productivity, or generally high and rising living standards, are unlikely to happen, so the lives of the non-elite are typically fairly poor. Extractive and subsistence-based pre-capitalist social institutions resulting in very low overall economic growth or economic stagnation (absence of intensive growth) have the additional consequence (Brenner, Citation2007) of structurally incentivizing the elite to chronically wage wars of territorial and populational acquisition from other elites, or simply to increase absolute surplus-extraction of their own producers (extensive growth), for purposes of maintaining their own reproduction in the society. This compounds the typical problem of low living standards among the non-elite, resulting in periods of extreme proneness to disease and depopulation. These and other trends and conditions are captured by the Malthusian perspective (which Sullivan and Hickel are critical of), though they should not be thought of as the result of non-social, natural, given forces (which Sullivan and Hickel are right to emphasize), but rather as a complicated interplay of demographic and institutional factors (see, on this, the recent review in Jedwab et al. [Citation2022]).

Living standards in Europe before and after the transition to capitalism

What were the living standards of precapitalist Europeans ‘at the bottom of the income pyramid’ (van Zanden et al., Citation2014, p. 25), i.e. those that can be proxied by data for real wages of unskilled laborers? below reuses the data displayed in above (Allen, Citation2001) but in a way that now distinguishes between the precapitalist European average and specifically London, where capitalism – on the definition and periodization advanced in the present study – was most clearly emerging since the 1600s. For an even more disaggregated presentation, refer to Figure 3a in the Appendix, which presents the same data but does so in a disaggregated way, so that one can observe the differences between different parts of Europe. shows that with the exception of capitalist cities such as London (and plausibly Antwerp and Amsterdam, see Figure 3a in the Appendix), living standards in early modern Europe were relatively close to the extreme poverty line defined by basic subsistence throughout the period. The non-capitalist European average for the 1500–1800 period can be calculated to be around $2.6, using the method suggested by Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023). The anomalous positive income shock that had been created by the Plague in the late fourteenth century, and which had lasted throughout the fifteenth century (see ), finally ended in the decades before 1500, opening the door to deteriorating living standards just mentioned. In non-capitalist cities, this deterioration could not be resisted given the constraints of the pre-capitalist economy. In cities witnessing the emergence of capitalist economic structures, such as in London, deterioration of living standards was able to be resisted.

Figure 5. Real daily income per person in a family of four with one working as an unskilled laborer (2011 welfare-adjusted PPP $), 1301-1900. Source: original ‘respectability’ welfare ratios from Allen (Citation2001) for unskilled laborers; for the source of the complete numerical sample see the note on data sources in the Appendix. ‘Respectability’ welfare ratios have been recalculated in two ways. First, to reflect 4.2 consumption baskets (instead of 3.15) in line with Allen (Citation2015) and Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023). Second, to transform them into real daily income for purposes of extreme-poverty comparisons, they have been further recalculated in line with Sullivan and Hickel’s (Citation2023) note, namely, Allen’s original figures have been multiplied by 4.33.

This is how Allen (Citation2001) himself interprets the dynamic:

The economic expansions of the Netherlands and England during the early modern period were important achievements, for they marked a departure from the Malthusian past. For the first time in western history, the economy kept pace with the population. If real wages did not rise dramatically, at least, they did not collapse. Continental Europe was not so lucky, and population growth there resulted in extremely low wages. The result was a substantial income gap with implications for health, consumer demand, and other aspects of life.

The pre-Industrial Revolution ran from roughly 1620 to 1770, when the Industrial Revolution began. This is the period when sustained economic development began in Britain, and it was marked both by a 50% rise in output per worker … and a general increase in real wages. This was a marked break from the usual Malthusian pattern that characterized pre-industrial economies. In such economies, wages were normally at subsistence. Demographic shocks such as plagues caused wages to rise, but they then gravitated back to subsistence.

displays real daily income calculated based on Allen’s (Citation2001) welfare ratio data for European craftsmen, which were skilled artisans with higher status and better living standards than common laborers; the social standing of these craftsmen was above commoners but below that of burghers, or the wealthy bourgeoisie, and nobles. For a disaggregated presentation of the whole sample, one should refer to Figure 4a in the Appendix. The data in show a similar pattern, although the absolute living standards of craftsmen were notably and unsurprisingly better in comparison to laborers. First, there is a significant deterioration in the precapitalist European welfare ratio average after the end of the fifteenth century positive income shock. Second, in comparison to ordinary laborers, craftsmen in most precapitalist regions never lived close to or even below basic-necessities poverty line. Third, the living standards of craftsmen were much higher, and resisted deterioration, in capitalist London (or Antwerp and Amsterdam).

Figure 6. Real daily income per person in a family of four with one working as craftsman (2011 welfare-adjusted PPP $), 1301-1900. Source: original ‘respectability’ welfare ratios from Allen (Citation2001); for the source of the complete numerical sample see the note on data sources in the Appendix. ‘Respectability’ welfare ratios have been recalculated in two ways. First, to reflect 4.2 consumption baskets (instead of 3.15) in line with Allen (Citation2015) and Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023). Second, to transform them into real daily income for purposes of extreme-poverty comparisons, they have been further recalculated in line with Sullivan and Hickel’s (Citation2023) note, namely, Allen’s original figures have been multiplied by 4.33.

Both sets of data are inconsistent with the standard narrative that the living standards of the majority were below extreme poverty in post-fifteenth century precapitalist Europe, as already demonstrated by Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023). Nevertheless, beyond this important point of agreement, my further interpretation of the data starts diverging from that offered by Sullivan and Hickel.

Relying on their , which depicts two regional averages for laborers’ daily real wages (calculated on the basis of Allen, Citation2001), one drawn from Polish, German, Austrian, Italian, and Spanish cities (what they call ‘European periphery’), and the other drawn from cities of England, France, and the Low Countries (‘European core’) they note the following. There is a notable increase in wages between 1375 and 1450; a slow but steady decline between 1450 and 1525; and lastly, a relative stagnation between sixteenth and mid-nineteenth century. There is also a notable divergence between the two regions, with the ‘European core’ oscillating at a notably higher living standard level than ‘European periphery’. Their interpretation of these events has two important parts.

First, the period between 1375 and 1450 is presented as evincing relatively high living standards due to laborers and peasants mounting successful rebellions against the elite, causing wages to rise. Although they nowhere explicitly claim that the relatively high living standards of this period were in principle sustainable indefinitely (at least from now on, with the ostensibly less oppressive social institutions emerging out of successful rebellions), one could get that very impression, especially so in light of the second part of their interpretation that follows below. To repeat, this is not an explicit claim that I am attributing to the authors. Instead, I take it as an interesting standalone claim that is worth arguing against, pace Sullivan and Hickel.

Second, they claim that it was subsequently only with the rise of ‘a novel economic system,’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 5) namely capitalism, that European elites during the long sixteenth century plunged their populations towards extreme poverty.

There are four critical observations to make in response to this. First, the 1375–1450/1500 higher income period could only ever have been a short-run exception to the general pattern of precapitalist farming societies normally roughly stagnating somewhat above subsistence. As Allen (Citation2020) noted in a recent widely acclaimed 2020 paper:

Welfare ratios have been computed for many places in Europe back into the Middle Ages, in the Americas back to the sixteenth century, in Asia for the past several centuries, and in Sub-Saharan Africa in the nineteenth century. These series typical exhibit four characteristics: (a) no upward or downward trend until the onset of modern long run growth, (b) preindustrial stasis at about subsistence (although exactly what level depends on the deflator used), (c) very low frequency cycles, and (d) short-run increases after demographic collapses such as the Black Death in 1348 or 1349.

The fall in population resulting from the Black Death thus had positive effects on real wages and income. Land prices, interest rates, and inequality fell. This increase in incomes–albeit temporary in a Malthusian setting–may have encouraged urbanization in the following centuries.

Third, the post-1500 drop in European living standards back close towards subsistence was not created (or associated) with the transition to capitalism, at least on the definition of capitalism advanced by this paper. Only one, or at most two, European countries started engendering capitalist economic institutions and practices around the sixteenth century, namely, England and the Netherlands; and these were the only places where living standards did not collapse below subsistence from their previous peak. Between 1500 and 1800, the empirical pattern associated with capitalism, namely, sustained, ‘endless’ increases in GDP per capita and a systematic rise of labor productivity, shows up only in England (and to an extent in the Netherlands) and nowhere else in Europe.

Fourth, Sullivan and Hickel’s own world-systems theoretical perspective – which they do not try to empirically justify but instead take as a given presupposition – seems inconsistent with some of the poverty data they present. For instance, following Wallerstein (Citation1974/Citation2011a, Citation1980/Citation2011b), they say that England, the Low Countries, and Northern France represent the European capitalist core. But the laborer welfare ratio data for Paris and Strasbourg (the only two cities they can take from Allen to represent Northern France) show clear divergence with the actually capitalist regions (London, Antwerp, and Amsterdam). Laborers’ living standards declined in Paris and Strasbourg with the alleged creation of the European capitalist core after 1500, while they are increased and/or maintained in Antwerp, Amsterdam, and London. It seems implausible that these cities, which embody very different socio-economic dynamics, constitute a common capitalist core.

In sum, according to my interpretation of the events, it was precisely the transition to capitalism in Britain that was associated with improvements in living standards, or at least resistance to deterioration towards subsistence levels, and it was the non-transition to capitalism, namely, the passing of the short-run demographic income shock and the transmutation of pre-capitalist feudalism into pre-capitalist absolutism on most of the continent (as argued by Marxist and non-Marxist historians alike, see Parker, Citation1996/Citation2014; Teschke, Citation2003; Lacher, Citation2006; Brenner, Citation2007; Isett & Miller, 2017; see also the review in Jedwab et al., Citation2022), that was associated with declining living standards close to subsistence in these other regions.

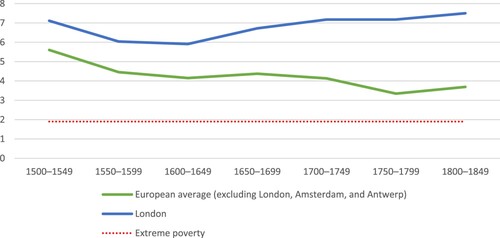

Setting wage-based measures of living standards aside, we should also look at other evidence to get a glimpse into the past. presents skeletal-based evidence of average male height in Europe between the 1st and eighteenth century. Height is an important indicator of living standards because, as Baten and Blum (Citation2014, p. 162; see also Section III in the Appendix) find, ‘the major determinants of biological well-being and, hence, height, are the quality of nutrition and the disease environment, whereas geography is a minor determinant.’

Figure 7. Average European male height (cm), 1st-eighteenth century. Source: Koepke and Baten (Citation2005).

The data in call for two observations. First, overall, there is great constancy throughout the period, with the average height barely oscillating around 170 cm (169–171 cm between 12th and eighteenth century); mind the severely truncated Y axis. There is no notable deviation of height if we compare the whole 16th – eighteenth century period, when the capitalist world-system was ostensibly created, with the whole 10th – fifteenth century period. Both periods see small increases and declines, but there is no overall pattern. There is a short-run downturn during the seventeenth century due to ‘nutritional crisis’ (Koepke & Baten, Citation2005, p. 76), a downturn comparable to the one during the thirteenth century. Second, in comparison to prehistory (see the first row of below), when nutrition had been better than in later farming class societies, average European height was considerably and consistently lower in medieval (or early modern) Europe. Note, however, that the reliability of data used in plotting is lower for the period between the 16th and eighteenth century, because the sample size is smaller. For this reason, see the more reliable data for individual country-cases (and a more detailed discussion about the association between height and the transition to capitalism) in the Appendix, Figures 5a, 7a, 9a, 11a, and 13a; see also the Swedish data for life expectancy after reaching 15 years of age in the Appendix (Figure 14a).

Table 3. Health-based indicators of living standards in the prehistorical and farming periods of the Eastern Mediterranean (and the modern U.S.)

presents a variety of living standards indicators mostly for the same location spanning both prehistory and precapitalist farming historical periods. Consistent with the preceding, these data show that, first, living standards in the Middle Ages as proxied by pelvic inlet depth and body height were notably poorer as compared to Late Paleolithic prehistory and comparably as poor as in other post-Neolithic periods with farming societies, excepting the modern period. Median lifespan was also extremely short, though no shorter than in prehistory. An inference can be made that living standards (at least as proxied by these measures) in the Middle Ages before the emergence of capitalism could not have been high, given the narrowed pelvic bone and stunted height as compared to either prehistory or modernity (for data on adult life expectancy see Figure 14a in the Appendix and the associated notes).

Second, note that the ostensible rise of the capitalist world-system in the 1400–1800 period mostly does not evince a clear and abrupt collapse of living standards as compared to the previous historical periods characterized by farming, though there is a notable drop in the median male lifespan. According to Wallerstein’s research notes (Citation1979), one important part of the Eastern Mediterranean, namely, the Ottoman Empire, had likely been incorporated into the capitalist world-system during the late eighteenth century (or by the nineteenth century at the latest). However, on my definition and periodization of capitalism, the Ottoman Empire was not capitalist, not even at the beginning of the twentieth century (see the recent case study in Duzgun, Citation2019, which argues the same).

A final source of non-wage evidence of European living standards comes from famine data. presents the findings of Alfani and Ó Gráda (Citation2018), the same dataset relied on by Sullivan and Hickel in their paper. Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023) present only the combined data for what they call ‘Northern Europe’, while below presents disaggregated data by individual country or region as presented in the original Alfani and Ó Gráda (Citation2018) sample. It can be seen that famines were comparatively much more frequent before the onset of capitalism, and that they virtually disappeared afterwards. As Alfani and Ó Gráda (Citation2017, p. 1, 7) themselves interpret the data,

It is a widely held belief among historians, economic historians and historical demographers alike that situations of severe food scarcity were quite commonplace in medieval and early modern Europe (though some countries – such as England – are usually considered to have been able to ‘escape’ from famine much earlier than others). … the most developed parts of the continent (i.e. the Netherlands and England) were the first to become famine-free, or almost so.

Table 4. Number of famines and famine-years in selected European countries, categorized according to the onset of capitalist ‘endless growth’, 1200s–1900s.

Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023, p. 7) conclude their review of the European evidence by stating that, ‘The rise of capitalism, rather than delivering improvements in human welfare, was associated with plummeting wages, a reduction in human stature, and a marked upturn in the incidence of famine.’ What has been presented in this paper strongly challenges their conclusion and suggests that almost the complete opposite is more likely the case.

The global perspective

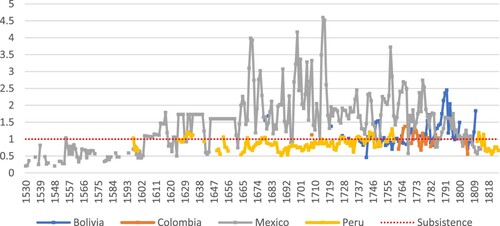

At least since the early modern period on, and up until around 1900, large parts of the non-European world were mired in extreme poverty. Existing data on historical welfare ratios are mostly available for the Americas and Asia, with the series of Africa being available only after the late 19th, early twentieth century on. That is why below present the welfare ratio data for Latin America and Asia but not for Africa (Africa is discussed in the next section).

Figure 8. Welfare ratios of unskilled Latin American laborers, 1530-1824. Source: Arroyo Abad et al. (Citation2012). See Appendix for more. Welfare ratios recalculated to reflect 4.2 consumption baskets (instead of 3.15) in line with Allen (Citation2015) and Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023).

Figure 9. Welfare ratios of unskilled Asian laborers, 1730-1970. Sources: Allen et al. (Citation2011) and de Zwart et al. (Citation2014). See Appendix for more. Welfare ratios recalculated to reflect 4.2 consumption baskets (instead of 3.15) in line with Allen (Citation2015) and Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023).

Figure 10. Welfare ratios of unskilled laborers in Indian regions, 1595-1916. Source: Allen (Citation2007); for the source of the complete numerical sample see the note on data sources in the Appendix. Welfare ratios recalculated to reflect 4.2 consumption baskets (instead of 3.15) in line with Allen (Citation2015) and Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023).

Relying on the same data, Sullivan and Hickel acknowledge the fact of long-run historical poverty but argue that it does not corroborate the standard narrative, according to which the absence of capitalism is correlated with poor living standards. Instead, they claim that the data support their critical view. They note that the early modern period is characterized by the expansion of (ostensibly capitalist) European countries outward and beyond Europe into the Americas and Asia.

clearly shows that with the exception of Mexico in the 17th – eighteenth century, the general pattern in Latin America is life at the basic-needs poverty line almost throughout the colonial period. (For an accounting of the Mexican exception, see Section V. in the Appendix; also note that there is one more exception not shown in the figure, namely, Argentina, where welfare ratios were much, much higher (see Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 8)). Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023, p. 7) claim that ‘Spanish and Portuguese conquest of the Americas from 1492 marked the bloody expansion of capitalism into the Western Hemisphere’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 7). Based on the association between capitalism (via Spanish and Portuguese colonialism) and extreme poverty in Latin America, they then conclude that the two are somehow – either causally or conceptually – linked.

How plausible is such a link? Spain and Portugal were not capitalist economies characterized by the typical pattern of ‘endless growth’ at the time of colonization (or in the centuries afterward up until late nineteenth century) but were instead typical precapitalist Malthusian economies (see above). It is thus hard to argue, outside of the particular Marxist world-systems perspective, that the bloody Spanish and Portuguese colonialism represented the ‘expansion of capitalism into the Western hemisphere’. Moreover, whatever the domestic economic structures of Spain and Portugal, these two colonial powers clearly did not bring capitalist institutions with them to the Americas. This is evinced by the colonized American economies exhibiting the same precapitalist Malthusian economic pattern until well into the nineteenth century (see the data in Bolt and van Zanden, Citation2020). It is also argued for in the theoretical and qualitative scholarly work by both non-Marxist (e.g. Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012) and Marxist (e.g. Wood, Citation2003) researchers. Finally, data on welfare ratios in the Aztec Empire before the European conquest of 1519 (see ) clearly show that the majority of the population (51.06%) was living in extreme poverty (significantly below a welfare ratio of 1), and another 43.33% of the population were on the edge of extreme poverty (at a welfare ratio of exactly 1).

Table 5. Welfare ratios for selected social strata of the Aztec Empire, dated just before the European conquest, i.e. before 1519.

Therefore, causally or conceptually tying the reality of extreme poverty in the colonized Americas to capitalism (via the European practice of colonialism) is highly dubious, and in any case not convincingly demonstrated or argued for by Sullivan and Hickel. This issue is compounded by the fact that Latin American welfare ratios start improving within the nineteenth century just as Latin American economies in fact start transitioning to capitalist institutions and post-Malthusian ‘endless growth’ (see Appendix, Figures 15a and 16a). The issue of whether colonialism (and extreme poverty) can be tied to capitalism is explored in much more detail in the next section.

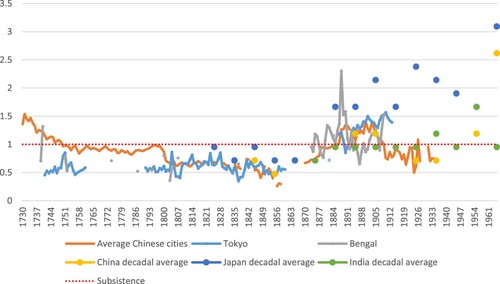

What about Asia? Turning to , it can be seen that life below subsistence was the norm between 1730 and 1870 for laborers in Tokyo and Bengal. Chinese cities (Beijing, Suzhou/Shanghai, and Canton) present a more complicated pattern. For a short period in the early eighteenth century, laborers lived above subsistence. Between 1750 and 1800, laborers lived slightly below subsistence. After 1800, extreme poverty in China becomes more clearly evident until the second half of nineteenth century, when it recedes but only to return in the first half of the twentieth century (for the case of Java, which is not plotted here, see Appendix, Section VII).

Before continuing, note that in their own depiction of the data, Sullivan and Hickel do not plot Japanese data, even though the values appear in the same paper and dataset they cite and draw upon to depict Chinese and Indian living standards. In fact, they never mention Japan or Japanese cities anywhere in their own paper. Perhaps they have a good analytical reason for this, but they do not state it. Whatever the case may be, the data for Japan are crucial to the present discussion for two reasons. First, Japan was isolated from Western contact and colonialism in the 18th and first half of nineteenth century, which means that it offers a pristine case for evaluating non-European living standards before capitalism (or European colonialism). Second, Japan is an interesting case because the welfare ratio data are in complete contradiction to Sullivan and Hickel’s critical narrative.

Unskilled Japanese laborers had been living in extreme poverty throughout the 1741–1865 period for which the data are available and presented in . Japan started being influenced by European (or American) colonialism in 1853, when Commodore Matthew Perry’s warships arrived and ended Japanese isolation (for a contemporary Marxist-based historical account of these events and the subsequent Japanese transition to capitalism see Cohen, Citation2015). Moreover, soon after Western contact, Japan’s economy started modernizing and exhibiting the typical capitalist pattern of ‘endless growth’ (see Cohen, Citation2015; and Figure 17a in the Appendix). Notably, at the same time, living standards started rising and extreme poverty was being eradicated (see ). The stark difference between Japanese living standards before and after the second half of nineteenth century is also evinced by the presence and absence of famine in the country (see below).

Table 6. Famines in Japan, 1300–1900 (no famines after 1900).

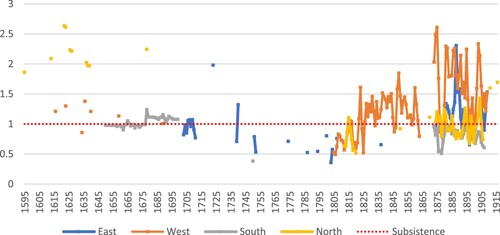

Setting the issue of Japan aside, let us turn to how Sullivan and Hickel interpret Indian data. They claim that ‘the rise of capitalism began to influence human welfare on the Indian subcontinent from the 17th century’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 11). To establish that India was specifically under capitalist – instead of generally colonialist – influence at the time, they again refer to Wallerstein. Using Allen’s (Citation2007) data for four Indian regions, they plot a series they call ‘Average India’, and conclude that, ‘prior to colonization, India’s real wage was generally higher than the extreme poverty line.’ (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 11). plots the same data but keeps them regionally disaggregated.

indeed shows that living standards in two Indian regions, North and West, were comfortably above subsistence in the seventeenth century, with the Northern region even having very high living standards. This is a surprising and important finding that clearly challenges the standard narrative about extreme poverty before capitalism (on this, see the discussion in Allen, Citation2007). In the East and South, however, living standards were much closer to subsistence in the second half of 17th and early eighteenth century. Later, with further European colonial expansion in the eighteenth century, Indian living standards fell further below subsistence. They started improving in the nineteenth century, but not notably above subsistence (except for the West, where improvement was more impressive), with the British assuming direct and formal control of the colony. This is a more complicated story than the one presented by Sullivan and Hickel, although their central contention that living standards were better (and above extreme poverty) before colonialism and only deteriorated (where they did) after colonialism does hold and is important to underline (see already Allen, Citation2007, pp. 28–29). Of course, one should also keep in mind Allen’s (Citation2020) warning about Indian data, which is that ‘in view of the fragility of the evidence, these observations should be read as provocations for further research rather than definitive conclusions.’

Turning lastly to China, Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023, p. 13) claim that ‘The incorporation of India after 1757 brough the capitalist world-system to China’s border.’ Britain and France forced the Qing state to reduce tariffs, and British consuls engaged in ‘semi-slave’ trade in Chinese servants. Their figure shows that before 1757, when the capitalist world-system had not yet influenced China, laborers lived slightly above or at subsistence. Thereafter, living standards fell below subsistence (dropping significantly in most of the nineteenth century). The implication is once again that living standards were worse after capitalism came to China.

Note, first, that although Chinese living standards were indeed above subsistence in the first part of the eighteenth century, they also exhibited a persistent negative trend throughout this period (between 1730 and 1750). The entirety of the deteriorating trend shows up before the colonial impact of 1757 that Sullivan and Hickel mention. After 1757, Chinese laborers are mostly stagnating (slightly below subsistence), and they do not deteriorate further. Second, and more importantly, the main question that remains unanswered is whether British and French colonial impact on China (and European colonialism in Latin America and India) can be either causally or conceptually tied to capitalism. If, pace Wallerstein, it cannot be, then poor living standards in China (and elsewhere) are indeed a reflection of colonial – and perhaps certain non-colonial factors that were present before 1757 – but not of capitalism.

The same issue is related to the African case, which is not depicted here. Data on welfare ratios of African laborers exist almost exclusively from the late nineteenth century and beginning of twentieth century on, Ghana being an important exception. Like in most of Latin American and Asian cases, data for Africa show life below subsistence in the colonial era (see Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023, p. 10). Living standards start improving – to the extent that they do, and not throughout the region – only around mid-century with the onset of decolonization and the coming of economic development; however, the two datapoints existing for Ghana before colonization suggest an absence of extreme poverty at that time (Sullivan & Hickel, Citation2023). The main question behind all of these patterns, then, is to what extent are colonialism and its effects (including poverty) related to capitalism. The paper turns to this question in the next section.

Extreme poverty and colonialism in the context of capitalism

Sullivan and Hickel (Citation2023, pp. 7–13) provide a robust overview of the extent, timing, injustice, and sheer brutality of European colonialism around the world. There is also no disputing the well-established long-term consequence of European colonialism on most of the colonized regions (excepting Western offshoots), namely its stifling of future economic development through either the establishment or entrenchment of precapitalist, extractive political and economic institutions (see Acemoglu et al., Citation2001; Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012). These pernicious effects persist to the present day. However, none of this by itself establishes the connection that Sullivan and Hickel presuppose exists between the practice and consequences of colonialism generally and capitalism as an economic system specifically. To what extent, and in what way, is the emergence of capitalist economic institutions and the pattern of ‘endless growth’ in early-modern England (or nineteenth-century France and Germany) tied to the brutality of European colonialism globally?

In this paper, I propose four general sets of reasons that could, if true, plausibly undergird the conceptual or causal connection between the two. Before unpacking and testing them, however, a potential misunderstanding should be clarified and avoided. The four reasons detailed below stem from the definition of capitalism advanced by the present paper, namely, capitalism as a particular set of social institutions and practices which, if present in a given social setting, make that social setting (say, a city or a country) capitalist. Working from a different definition of capitalism (such as the one offered by the world-systems perspective relied on by Sullivan and Hickel), one could well advance other reasons than the four outlined below for thinking that capitalism and colonialism are connected. For instance, if capitalism is seen as an overarching, transnational macro-system (instead of as a more meso-level set of institutions and practices) and if its conceptual core is defined in terms of intersocietal trade relations with a particular ‘division of labor’ (instead of intrasocietal competitive relations among market-dependent economic actors), as it is in Wallerstein’s (Citation2011b) world-systems theory relied on by Sullivan and Hickel, then one could very well maintain both that most of Europe itself was capitalist already in the early-modern period and that European colonies were likewise capitalist simply in virtue of being inserted into the European circuit of trade and its ‘division of labor’. This is not necessarily illegitimate on my view because, as mentioned before, I recognize definitions are tautologies that cannot be empirically tested, so cannot be ‘false’ or ‘true’. Of course, there exist unending conceptual debates between anti-Wallerstein Marxists (such as Wood, 2001; Brenner, Citation2007) and pro-Wallerstein Marxists (and even Marxists somewhere in the middle, such as Anievas & Nisancioglu, Citation2015) on the topic of whether his definition of capitalism is ‘correct’. Moreover, world-systems theory has likewise been broadly disputed amongst non-Marxists. The theory has been challenged as functionalist, economistic, too macro-centric, too trade-centric (or ‘neo-Smithian’), ahistorical, reductionist, etc. (Skocpol, Citation1977; Brenner, Citation1977; Zolberg, Citation1981, p. 255; Mann, Citation1993, p. 270; Anievas & Nisancioglu, Citation2015, pp. 19–22). I would not want to rehash these futile debates and so I do not intend to ‘refute’ Wallerstein’s conception of capitalism due to it being, say, ‘too functionalist’ or ‘ahistorical’. I pragmatically accept Sullivan and Hickel have successfully demonstrated their conclusions, basing themselves on that particular definition of capitalism.

Instead, the purpose of the present paper is simply to advance a different conception of capitalism – one that incidentally has the quality of being widely accepted in different parts of social sciences and across many ideological divides – and to check whether Sullivan and Hickel’s conclusions remain robust to such a change in definition (and, consequently, periodization) of capitalism. As I argue below, on my definition of capitalism, the link between capitalism and colonialism is neither baked into it from the start nor definitionally excluded from it a priori, which I take to be a solid, because fair, analytical starting point. The definition of capitalism advanced in the present paper allows for four general, analytical sets of reasons to contingently (depending on the concrete empirical circumstances) tie capitalism and colonialism together or not.

First, colonialism could be said in the most general sense to be capitalist if perpetrated by a country that is itself characterized by capitalist institutions and patterns. On this account, early-modern and modern British (and Dutch) colonialism qualifies as capitalist, but Spanish, Portuguese, and French (German, etc.) colonialism does not, at least not until the ‘New Imperialism’ of the late nineteenth century. One potential issue with this categorization is that it is unclear both conceptually and causally how capitalism and colonialism are specifically linked, except for the general sense that the domestic economic structures of a state perpetrating colonialism are capitalist in nature. On this general account, it is simply that some countries were capitalist and some were not, but all (or most) practiced colonialism either way.

Second, colonialism could be more specifically and distinctively characterized as capitalist if it has the effect of infusing capitalist economic institutions to the colony, namely if it manages to coercively replace the autochthonous economy in the colony with a capitalist one. On this account, British colonialism in what would become the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand qualifies as capitalist. In these cases, the colonists brutalized, murdered, and almost completely eradicated the original nomadic and complex hunter-gatherer populations and their societies, replacing them with British-based economic and political institutions that would over time amount to full-fledged capitalism (Wood, Citation2003; Acemoglu et al., Citation2001; Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012). What would become the United States already started showing clear signs of ‘endless growth’ in the eighteenth century (Bolt and van Zanden, Citation2020). GDP data for the other three Western offshoots are available only for nineteenth century, but they too show clear signs of capitalist growth since the beginning of their respective timeseries (Bolt and van Zanden, Citation2020).

However, British colonialism in India and elsewhere does not qualify as capitalist on this criterion, as it did not cause the transition to capitalism in the colony. This was not for a lack of trying. The British strove to establish capitalist social-property relations in India but were unsuccessful (Wood, Citation2003; Metcalf & Metcalf, Citation2012). The same goes for most of the Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Dutch invasions, which did not result in the establishment of capitalist institutions in Latin America and Asia in the early modern period, nor later still in the late nineteenth century ‘scramble for Africa’ (Wood, Citation2003; Acemoglu et al., Citation2001; Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; Isett & Miller, 2017).

Third, colonialism could also be convincingly said to be capitalist if driven or motivated by ‘the logic of capital’, i.e., if social actors are compelled to engage in colonialism due to capitalist structural forces and mechanisms that comprise their social setting. Here, one obvious link between the two could be the capitalist motive of economic gain, namely, the profit motive; clearly European colonialism was in part driven by such prospects. However, as Marxist researchers such as Wood (2001, Citation2003) have pointed out, mere monetary gain, market exchange, and the profit motive are not in fact distinctively capitalist phenomena. These are millennia old economic institutions and practices, and they have been implicated in driving early modern colonialism as much as other instances of empire throughout the recorded human history. Something more specific would be needed to implicate capitalism per se with colonialism.

Following Hobson (Citation1902/Citation1988), famous Marxists such as Lenin (Citation1917/Citation1939) hypothesized that European colonialism during the era of ‘New Imperialism’ was driven by the structural capitalist ‘need’ to export surplus capital. The idea was that the pressures of market competition and various capitalist internal contradictions (such as monopolization and concentration) made it necessary for capital to seek economic outlets elsewhere around the globe. Theoretically, arguments such as these more convincingly flesh out the distinctive hypothetical link between capitalism and colonialism than merely pointing to the profit motive, although the problem with this particular thesis is that it turns out to be empirically wrong. As Mann (Citation1993, p. 777) puts it,

There was no capital surplus. … Only a few colonies in this period were established because of specifically capitalist pressure; few were seen as good export markets; and colonial expansion in the late nineteenth century did not pay its way for any country. … [T]he new imperialism in Britain was not caused by need to export capital … (Mann, Citation1993, p. 777).

Capital exports to the colonial periphery, although rising sharply before the First World War, were significantly lower than capital exports (both portfolio and direct investments) between imperialist powers. Inter-imperial volumes of trade were significantly higher than imperial-colonial commerce. Colonial capital exports were small in absolute terms relative to domestic investments. Rates of return from colonial capital exports were not higher relative to the rates from domestic investment, yet subject to higher risks.

A notable textbook on Marxist theories of imperialism claims that, ‘All the evidence suggests that the long-run effects of empire on development of the imperialist centers was small.’ (Brewer, Citation2002, p. 83) The reality, however, is more complicated. In a large review paper, and specifically basing themselves on 6 detailed contemporary historiographical national case studies employing the balance of payments taxonomy and models derived from international economics (and other relevant material), O’Brien and de la Escosura (Citation1998, p. 54, 57) summarize the complex evidence by concluding:

[T]here no longer seems to be valid historical arguments for accepting traditional liberal perceptions which are traditionally prone to denigrate connexions between Britain’s successful pursuit of mercantilism, trade and empire on the one hand and its famous industrial revolution on the other. Nor is the alternative case (favoured by Marxists) that Britain deployed its overwhelming competitive advantage in naval power to build up a mercantile and industrial economy at the expense of its European competitors by exploiting the populations and resources of other continents, anything like the whole story. … [A]rguments that reify the expansion of Western Europe overseas into the engine of its economic success compared to continents (until recently represented as a Third World) should be resisted and severely qualified.

the positive correlations to long term growth seem visible enough in the British example. For example, a high but by no means a dominant share (but possibly up to 30 per cent to 40 per cent) of all the extra industrial output manufactured in Britain during the early stages of industrialisation, 1660–1815, was exported overseas; mainly to the Americas, Asia and Africa … For the First Industrial Nation there could be no gainsaying the positive connexions between imperialism, trade and long term economic growth, which by 1846 helped to elevate the British economy into the workshop of the world.

In noting this, we should also be distinguishing between the contribution of trade to the economic rise of a country and colonialism in particular. As the authors of the 2010 review remark (O’Rourke et al., Citation2010),

The conclusion that trade and growth were positively related during the period is an important one. However, it is less clear what the mechanisms linking trade with economic growth were. … [T]he literature very often (if understandably, given the realities of mercantilism) conflates two conceptually distinct issues, namely the impact of trade in general and the effect of countries’ colonial policies.

Other scholars, such as Pomeranz (Citation2000/Citation2021), Beckert (Citation2015) and Patnaik (Citation2017) among others, have recently disagreed with these verdicts. They point specifically to various aspects of European colonialism in the form of supply of raw materials, extra demand for British exports, or revenue drain as the predominantly important, even necessary, factor in unleashing capitalist development.

Situating himself in the revised ‘Williams thesis’ proposed by Pomeranz (Citation2000/Citation2021), Beckert (Citation2015), for instance, claims that American slavery was necessary for the Industrial Revolution because it provided Britain with the unique advantage of cheap slave-grown cotton, crucial for the efflorescence of its key industrial sector. However, this is not at all clear. As Clegg (Citation2015, p. 296) has noted, Britain’s cotton industry did not collapse or become diminished ‘without slave-grown cotton during and after the American Civil War,’ so it is doubtful that slave-grown cotton was necessary either for the expansion of this sector or even the whole British economy. Moreover, ‘when Britain was briefly cut off from American cotton imports by the war of 1812, the price of cotton rose less than it did in the 1860s, suggesting less dependence in this earlier period.’ (Clegg Citation2015) The real question, Clegg (Citation2015) notes,

is not whether Lowell or Manchester could have done without slave-produced cotton, but what they would have had to pay for it. A higher price may have put pressure on less efficient mills, but raw cotton was a small component of the final textile price, and demand was not particularly elastic.